Principles

and practice of poultry culture – 1912

John Henry Robinson (1863-1935)

Principi

e pratica di pollicoltura – 1912

di John Henry Robinson (1863-1935)

Trascrizione e traduzione di Elio Corti![]()

2016

Traduzione assai difficile - spesso incomprensibile

{} cancellazione – <>

aggiunta oppure correzione

CAPITOLO XVIII

|

[311] CHAPTER XVIII |

CAPITOLO XVIII |

|

|

PREPARATION OF POULTRY PRODUCTS |

PREPARAZIONE |

|

|

Dressed poultry. The number of steps in the preparation of dressed poultry varies according to the kind of poultry, the choice of methods, and the disposition to be made of it. The full list is (1) fasting, (2) killing, (3) scalding, (4) picking, (5) cooling, (6) shaping, (7) grading, (8) packing. |

Pollame preparato . Il numero di passi nella preparazione di pollame preparato varia a seconda del tipo di pollame, della scelta dei metodi e della destinazione di essere fatto di lui. Il pieno elenco è (1) digiuno, (2) uccisione (3) scottatura, (4) scelta, (5) rinfresco, (6) modellamento, (7) selezione, (8) imballaggio. |

|

|

Fasting. Before being killed, poultry should be fasted (starved by withholding food and water) for from twenty-four to thirty-six hours, that when they are killed, the crop, gizzard, and entrails may be quite empty. This improves the appearance of the carcass. A dressed bird with crop bulging at one side of the breast is not at all attractive looking. Fasting also improves the keeping qualities of the carcass by removing from it offal already in a state of partial decomposition. Poultry to be used at home need not be starved, but unless it is to be cooked immediately after killing, it is better to keep the birds fasting for at least a day beforehand. Packers of poultry, as well as producers who ship their own product, sometimes feed and water shortly before killing, to increase the weight. Apart from the dishonesty of this, it does not always pay in the immediate returns, and always finally works to the disadvantage of those practicing it. In some places, offering poultry for sale with food in the crop is prohibited by law. Poultry dressed in this condition will shrink much more in weight during transportation than poultry that has been properly starved before killing, and the shipper who follows this practice is constantly in difficulty with his customers over short weights. The necessary shrinkage in weight from fasting is very slight, and is more than compensated for by better appearance, better condition, and (usually) by the better price received. |

Digiuno . Prima di essere ucciso, il pollame dovrebbe essere fatto digiunare (fatto morire di fame sopprimendo cibo e acqua) per 24 fino a 36 ore, cosicché quando viene ucciso il gozzo, il ventriglio e i visceri possano essere piuttosto vuoti. Questo migliora l'aspetto della carcassa. Un uccello preparato con il gozzo che si incurva su un lato del petto non è affatto di aspetto attraente. Il digiunare migliora anche le qualità di conservazione della carcassa rimuovendo da essa degli avanzi già in un stato di parziale decomposizione. Il pollame per essere usato in casa non ha bisogno di essere morto di fame, ma, salvo che sia immediatamente cucinato dopo averlo ucciso, è meglio tenere gli uccelli a digiuno per almeno un giorno in anticipo. Imballatori di pollame, così come produttori che inviano il loro proprio prodotto, qualche volta nutrono e danno da bere acqua poco prima di ucciderlo, per aumentare il peso. A parte la disonestà di ciò, non sempre ripaga con immediati guadagni, e alla fin fine sempre agisce a svantaggio di quelli che lo praticano. In alcuni luoghi l’offerta di pollame da vendere con del cibo nel gozzo è proibita dalla legge. Il pollame preparato in questa condizione si ridurrà molto più in peso durante il trasporto rispetto al pollame che è stato opportunamente tenuto a digiuno prima di ucciderlo, e lo spedizioniere marittimo che segue questa pratica è continuamente in difficoltà coi suoi clienti circa i pesi scarsi. La necessaria diminuzione in peso con il digiunare è molto esigua, ed è più che compensata dal migliore aspetto, dalla condizione migliore, e (di solito) dal miglior prezzo ricevuto. |

|

|

Killing. When dressed poultry is to be sold in the open markets the method of killing is determined by the style of dressing [312] that the market demands. When it is to be used by the producer or sold direct to consumers, the method easiest for the poultryman may be used, provided it is not objectionable to consumers. The common methods of killing are wringing the neck, dislocating the neck, cutting off the head, and sticking (with a knife). |

Uccisione . Quando il pollame vestito deve essere venduto nei mercati aperti, il metodo di uccidere è determinato dallo stile del vestire che il mercato richiede. Quando deve essere usato dal produttore o venduto direttamente ai consumatori, può essere utilizzato il metodo più facile per l’avicoltore, purché non sia sgradevole per i consumatori. I metodi comuni di uccidere sono torcere il collo, slogare il collo, tagliar via la testa, e pugnalare (con un coltello). |

|

|

|

||

|

Wringing the neck. For birds not too large or too tough, and for one who has the strength and nerve to do it, wringing the neck is the easiest way of killing. The head of the bird is grasped firmly in one hand, and the neck is wrung and the head completely severed from the body in an instant by whirling the bird by the head, the hand of the person rapidly describing a few short circles. This is a common method of killing fowls and chickens for immediate consumption. When done with skill and on suitable birds, it is as humane as any method. When unskillfully done, or tried on birds with strong frames and tough skin, the usual result is strangulation without proper bleeding. |

Torsione del collo . Per uccelli non troppo grandi o troppo tenaci, e per uno che ha la forza e il coraggio di farlo, la torsione del collo è il modo più facile per uccidere. La testa dell'uccello è afferrata fermamente in una mano, e il collo è ritorto e la testa completamente staccata dal corpo in un istante rigirando l'uccello per mezzo della testa, con la mano della persona che traccia rapidamente alcuni cerchi corti. Questo è un metodo comune di uccidere uccelli e polli per il consumo immediato. Quando fatto con abilità e su uccelli adeguati, è tanto senza dolore quanto ogni metodo. Quando è fatto con imperizia, o tentato su uccelli con forti costituzioni fisiche e pelle dura, il risultato abituale è lo strangolamento senza evidente emorragia. |

|

|

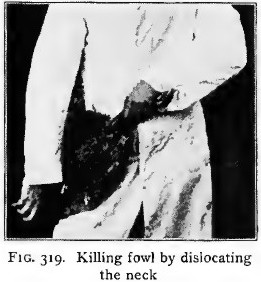

Dislocating the neck. Dislocating the neck is a method popular in Canada but not used in the United States. The legs and primary wing feathers are held in the left hand (as in cutting off the head), this hand being held near the waist. The head of the bird is grasped between the thumb and forefinger of the right hand, and bent back at a right angle to the neck, while at the same time, by a strong but short pull, the neck is broken close to the skull and the windpipe and arteries severed so that the bird will bleed freely. The skin is not broken, and the blood collects in the neck close to the head and clots there. |

Slogatura del collo . Slogare il collo è un metodo popolare in Canada ma non usato negli Stati Uniti. Le gambe e le principali penne dell’ala sono tenute ferme nella mano sinistra (come nel tagliare via la testa), essendo questa mano tenuta vicino alla cintura. La testa dell'uccello è tenuta stretta tra il pollice e l’indice della mano destra, e piegata indietro a un angolo retto rispetto al collo, mentre allo stesso tempo, con un forte ma corto strattone, il collo è rotto vicino al cranio, e la trachea e le arterie troncate in modo tale che l'uccello sanguinerà liberamente. La pelle non è rotta, e il sangue si raccoglie nel collo vicino alla testa e lì si raggruma. |

|

|

Cutting off the head. Cutting off the head is the method of killing most practiced with poultry that is not to be held long after killing, or not sent to markets which want birds with heads on. The bird is held in the left hand by the legs and the primary wing feathers, the wings being drawn back until these feathers can be grasped with the legs in the hand. The head is then laid on a block of wood and severed as close as possible to the juncture of the head and neck with a heavy hatchet or ax; whichever is used should have a straight, sharp edge. For killing a few birds occasionally, any block will do, but if much killing is done, it is best to have a solid chopping block about two feet high, with a smooth top, the surface of which will not be spoiled by the hatchet in a short time. After the head is severed, the bird should still be held in the hand, the neck over the edge of the block, the body held in this position by the flat side of the hatchet until the bird ceases to struggle, when it may be placed on the ground without danger of bruising itself in its [313] struggles. When many birds are killed, it is a good plan to have a pail or other vessels to catch the blood and prevent its being wasted.* |

Tagliare via la testa . Tagliare via la testa è il metodo di uccisione più praticato con il pollame che non deve essere tenuto per molto tempo dopo averlo ucciso, o che non va inviato a mercati che vogliono uccelli con la testa. L'uccello è tenuto nella mano sinistra con le gambe e le principali penne dell’ala, le ali essendo tirate indietro quel tanto che queste penne possono essere afferrate con le gambe nella mano. La testa è poi posata su un blocco di legno e troncata il più vicino possibile alla congiunzione della testa col collo con un'accetta pesante o ascia; qualunque cosa venga usata dovrebbe avere un bordo privo di curve, tagliente. Per uccidere di quando in quando alcuni uccelli, non si farà alcun blocco, ma se si uccide parecchio, è meglio avere un blocco da taglio solido alto circa 2 piedi, con una sommità liscia, la cui superficie non sarà rovinata dall'accetta in breve tempo. Dopo che la testa è troncata, l'uccello dovrebbe ancora essere tenuto nella mano, il collo sul bordo del blocco, il corpo tenuto in questa posizione dal lato piatto dell'accetta finché l'uccello cessa di dibattersi, quando può essere messo sulla terra senza pericolo di ferirsi nei suoi dimenarsi. Quando molti uccelli sono uccisi, è buona cosa avere un secchio o altri vasi per prendere il sangue e impedire che venga sprecato.* |

|

|

* The blood may be fed to poultry either separate or in mash. |

* Il sangue può essere dato da mangiare al pollame o separato o in mescolanza. |

|

|

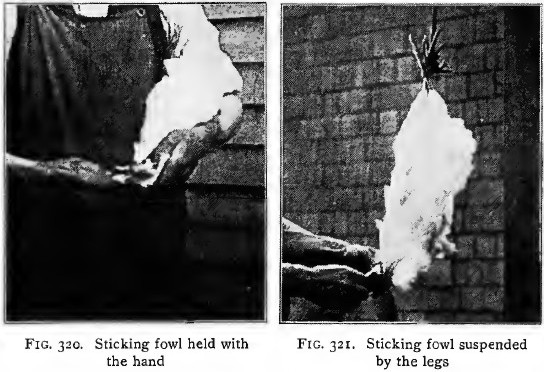

Sticking. Sticking is done with a short,** sharp knife, the cut being made either in the neck (outside), severing the jugular vein, or in the mouth (inside), piercing the brain. The latter method is preferred, because the cut is concealed. The bird is sometimes stunned by striking the head against a post or by striking with a stick on the head or back before sticking, but this tends to prevent proper bleeding, and is not as commonly practiced as formerly. The details of killing by this method vary considerably, particularly as to the position of the operator and of the bird when the cut is made. These depend upon the method of picking and upon whether each picker kills his own birds or whether one person does all the killing for a gang of pickers. |

Il conficcare . Il conficcare è fatto con un coltello corto,** tagliente, il taglio essendo fatto o nel collo (fuori), troncando la vena giugulare, o nella bocca (dentro), forando il cervello. Il secondo metodo è preferito, perché il taglio è nascosto. L'uccello è talora stordito sbattendo la testa contro un puntello o colpendo con un bastone sulla testa o sulla schiena prima di conficcare, ma questo tende a prevenire una vera e propria emorragia, e non è comunemente praticato come in precedenza. I dettagli di uccidere con questo metodo variano notevolmente, particolarmente a seconda della posizione dell'operatore e dell'uccello quando il taglio è fatto. Questi dipendono dal metodo di scelta e se ogni raccoglitore uccide i suoi propri uccelli o se una persona esegue tutte le uccisioni per una banda di raccoglitori. |

|

|

** Regular poultry-killing knives are short, but some pickers use a common butcher knife. |

** I coltelli regolamentari per uccidere il pollame sono corti, ma dei raccoglitori usano un comune coltello da macellaio. |

|

|

|

||

|

When each picker kills his own birds, one at a time as he wants them, he usually works sitting down, with a coop of live birds at one side and a box for feathers at the other, and holds the bird between his knees with the head extended from him while making the stick. Sometimes, however, especially when picking large birds not easily stuck in that position, the picker stands up and holds the body of the bird between his arm and his side, with the head extended forward in the left hand in a convenient position for sticking. |

Quando ogni raccoglitore uccide i suoi propri uccelli, uno alla volta come lui li vuole, di solito lavora seduto, con un pollaio di uccelli vivi da un lato e una cassa per le penne all'altro, e tiene l'uccello tra le sue ginocchia con la testa tesa lontano da lui mentre conficca. Comunque, specialmente raccogliendo grandi uccelli non facilmente bloccati in quella posizione, talora il raccoglitore si alza e tiene il corpo dell'uccello tra il suo braccio e il suo fianco, con la testa estesa in avanti nella mano sinistra in una posizione conveniente per conficcare. |

|

|

When one person does the killing for a number of pickers, as is usual when poultry is scalded, the birds are often suspended in loops, by the feet, [314] from a beam, and a hook with a weight attached, inserted in the upper mandible before the stick is made, prevents struggling. This method is also used in what is known as string picking, in which the bird is picked while suspended instead of being placed on a bench or held on the knees of the picker. |

Quando una persona esegue l'uccisione per un numero di raccoglitori, come è la norma quando il pollame è scottato, spesso gli uccelli sono sospesi a una trave coi piedi in lacci ad anello, e un gancio con un peso attaccato, inserito nella mandibola superiore prima che il bastone sia fatto, previene lottando. Questo metodo è usato anche in quello che è noto come raccolta con il cordoncino, nel quale l'uccello è scelto mentre è sospeso invece di essere messo su una panca o tenuto sulle ginocchia del raccoglitore. |

|

|

|

||

|

Methods of making the stick vary slightly, the object in all cases being the same, ― to penetrate the brain and paralyze the bird (causing the feathers to loosen so that they are easily removed), and to secure free bleeding. The method may perhaps be best described as a stab to the brain, well back in the roof of the mouth (the thrust cutting crosswise), then a twist of the knife to bring it into position, and a slit forward the entire length of the roof of the mouth. Skill in sticking depends first on acquiring the knack of it, and then upon practice. Even a good sticker does not always make a good stick. Diagrams are sometimes given to illustrate the cut, but it is to be doubted whether they are of any real assistance, for it is the sense of touch, more than anything else, that regulates the movement of the knife. The sticker knows when he has made his thrust right by a peculiar shiver which the bird gives and which he soon learns to recognize by touch. He presses the knife to the brain until he feels this, then turns it and cuts forward to give the blood free vent, being careful all the while not to cut through to damage the outside of the head and, perhaps, his fingers. When the bird is to be dry picked, the removal of the feathers is begun at once, the object being to have it picked quite clean before bleeding stops. When the bird is to be scalded, bleeding should be finished before scalding is done, or the heat may bring the blood to the skin and coagulate it there, spoiling the appearance of the carcass. |

Metodi di fare il bastone variano leggermente, lo scopo in tutti i casi essendo lo stesso ― penetrare il cervello e paralizzare l'uccello (causando le penne a liberarsi così da essere rimosse facilmente), e assicurare un’abbondante emorragia. Il metodo forse può essere meglio descritto come una pugnalata al cervello, bene indietro nel palato della bocca (il colpo che taglia trasversalmente), poi una torsione del coltello per portarlo in posizione, e una fenditura verso l’intera lunghezza del palato della bocca. L'abilità nel conficcare dipende innanzitutto dall’acquisire l'abilità di farlo, e poi dalla pratica. Anche una buona persona tenace non fa sempre un buon bastone. Diagrammi sono talora forniti per illustrare il taglio, ma si deve dubitare se sono di qualche vero aiuto, perché è la sensazione del tocco, più di qualsiasi altra cosa, che regola il movimento del coltello. Chi conficca sa quando ha dato il suo colpo giusto in base a un brivido caratteristico che l'uccello dà e che lui presto impara per riconoscere attraverso il tocco. Lui pigia il coltello nel cervello finché lo percepisce, poi lo gira e taglia in avanti per dare al sangue un foro libero, avendo cura per tutto il tempo di non tagliare di traverso per danneggiare l’esterno della testa e, forse, le sue dita. Quando l'uccello deve essere scelto asciutto, la rimozione delle penne è subito intrapresa, essendo l'oggetto di averlo scelto piuttosto pulito prima che il sanguinare cessi. Quando l'uccello deve essere scottato, il sanguinamento dovrebbe essere finito prima che lo scottare venga fatto, o il calore può portare il sangue alla pelle e coagularvelo, rovinando l'aspetto della carcassa. |

|

|

Scalding. This process is used much more extensively and with more satisfactory results than would be inferred from a perusal of most of the special articles and pamphlets on the preparation of poultry for market. It is the easiest way to remove the feathers. When properly done the scalded bird presents none of the defects of poorly scalded poultry, and can be distinguished from the dry-picked bird only by experts. Done carelessly or by one who does not understand it, scalding usually results in spoiling the appearance of every bird put through the process. |

Scottatura . Questo processo è usato molto più estesamente e con risultati più soddisfacenti di quanto si potrebbe dedurre da un’attenta lettura della maggior parte degli articoli speciali e degli opuscoli sulla preparazione del pollame per il mercato. È il modo più facile di rimuovere le penne. Quando fatto opportunamente, l'uccello scottato non presenta alcuno dei difetti del pollame scarsamente scottato, e può essere distinto dall'uccello scelto asciutto solo da esperti. Fatta in modo negligente o da uno che non la capisce, la scottatura di solito dà luogo al guastare l'aspetto di ogni uccello sottoposto al processo. |

|

|

[315] How to scald. The first thing in scalding poultry is to have a vessel of water large enough to allow free handling of the birds. The next thing is to maintain the water at the desired temperature as long as required. The temperature of the water should be just below boiling. When a single chicken or a medium-sized fowl is to be scalded, it may be done in a twelve- or sixteen-quart pail, by using enough water, boiling when taken from the stove, to make the pail a little over half full. In pouring or dipping from the kettle or the tank to the pail, the temperature of water at the boiling point will usually be sufficiently reduced by contact with the cooler air as the water passes from vessel to vessel. The bird should be taken by the feet and soused in the water in such a way that the feathers will be rumpled by the movement and the water will penetrate nearly to the skin without reaching it. If the bird is to be dressed with the head on, the head should not be scalded but held in the hand while the scalding is done. It is not as easy to scald in this way as with the head off, but with a little care good work may be done. When scalding is done properly, the effect at the root of the feather is to steam the skin without scalding it. The time required varies with the condition and density of the feathers. A chicken or a molting hen may need only a plunge so rapid that the skin is hardly affected, though the scantiness of plumage allows the water to touch it. A full-feathered fowl, especially an old one, may require several plunges. The effect on the feathers is ascertained by plucking a few from the thigh near the hock joint. If these come easily, there should be no difficulty in removing the others. Only one or two birds can be scalded in the same water in this way, but more may be scalded if boiling water is added. For larger birds a boiler or a tub may be used. Results of scalding in this way are not uniform, however, and if any considerable number are to be scalded, a set-kettle, under which a slow fire can be kept, should be used. This gives a body of water large enough for quick and thorough work in scalding, and after a few trials of the water on the stock with which he is working, an expert will put most of his birds through without a blemish due to poor scalding. If a bird has been well scalded, only the stiff tail and wing feathers need be pulled out. The others will rub off, except pinfeathers in birds not in full plumage. If handled immediately after scalding, the feathers are usually a little too hot for the comfort of the picker. They are removed just as easily after they become cool enough to handle, and with little greater difficulty at any time within ten or twelve minutes. |

Come scottare . La prima cosa quando si scotta il pollame è avere un vaso d’acqua grande abbastanza da permettere il libero maneggio degli uccelli. La cosa successiva è mantenere l'acqua alla temperatura desiderata finché richiesto. La temperatura dell'acqua dovrebbe essere appena al di sotto del bollire. Quando un solo pollo o uccello di media grandezza deve essere scottato, lo si può fare in un secchio di 12 o di 16 quarti di gallone, usando abbastanza acqua, che bolle quando presa dalla stufa, per fare il secchio pieno un po’ più della metà. Nel versare o immergere dal bollitore o dal serbatoio al secchio, la temperatura dell’acqua al punto d'ebollizione di solito sarà ridotta sufficientemente dal contatto con l'aria più fresca quando l'acqua passa da vaso a vaso. L'uccello dovrebbe essere preso dai piedi e immerso nell'acqua in modo tale che le penne saranno arruffate dal movimento e l'acqua quasi penetrerà fino alla pelle senza raggiungerla. Se l'uccello deve essere preparato con la testa in su, la testa non dovrebbe essere scottata ma tenuta nella mano fino a quando la scottatura è ultimata. Non è facile scottare in questo modo come quando non c’è la testa, ma con poca cura un buon lavoro può essere fatto. Quando lo scottare è fatto come si deve, l'effetto alla radice della penna è esporre la pelle al vapore senza scottarla. Il tempo richiesto varia con la condizione e la densità delle penne. Un pollo o una gallina che fa la muta possono avere bisogno di solo un tuffo così rapido che la pelle è a malapena colpita, sebbene la scarsezza di piumaggio permetta all'acqua di toccarla. Un uccello assai pennuto, specialmente uno vecchio, può richiedere molti tuffi. L'effetto sulle penne è accertato strappandone alcune dalla coscia vicino alla giuntura con la zampa. Se vengono via facilmente, non ci dovrebbe essere difficoltà nel rimuovere le altre. Solamente 1 o 2 uccelli possono essere scottati così nella stessa acqua, ma di più se ne può scottare se è aggiunta dell’acqua bollente. Per uccelli più grandi può essere usata una caldaia o una vasca. I risultati della scottatura così fatta non sono uniformi, comunque, e se un numero considerevole deve essere scottato, dovrebbe essere usato un bollitore, sotto il quale può essere mantenuto un debole fuoco. Questo dà un volume d’acqua grande abbastanza per un lavoro rapido e completo nello scottare, e dopo alcune prove dell'acqua sul bestiame con cui sta lavorando, un esperto metterà la maggior parte dei suoi uccelli completamente senza un difetto dovuto a una povera scottatura. Se un uccello è stato scottato bene, solo la coda rigida e le penne delle ali hanno bisogno di essere tolte. Le altre verranno tolte sfregando, eccetto le penne nascenti in uccelli non nel pieno del piumaggio. Se toccate immediatamente dopo la scottatura, le penne sono di solito un po’ troppo calde per la comodità del mondatore. Sono rimosse facilmente solo dopo che diventano fresche abbastanza per essere toccate con le mani, e con una piccola maggiore difficoltà entro 10 o 12 minuti. |

|

|

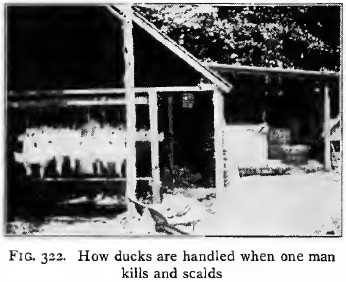

Ducks and geese. Waterfowl are much more difficult to scald than other poultry. Their dense plumage is not so easily penetrated by the water, and the ease with which the feathers on the thigh are removed is not as accurate an index of the general condition. A common practice is to wrap them in burlap (old grain sacks) after scalding, and allow them to steam in the hot, wet feathers for some minutes before beginning to pick. Even then a supplementary scald is sometimes necessary, after a part of the feathers have been removed. In packing establishments steam is often used for scalding, giving a dry scald. The steam used is sometimes taken from a pipe or a hose, but direct steaming is said to be more satisfactory. Some of the smaller packing establishments use [316] a method of steaming ducks which may be applied anywhere. On a common round, wide-topped laundry stove is placed a wash boiler with about three or four inches of water in the bottom; in the boiler is a wooden frame which holds the bird in the steam without allowing it to get into the water. The bird is placed in the boiler and steamed for about one and one half minutes on one side, then turned and steamed for about the same length of time on the other side. |

Anatre e oche . Gli uccelli acquatici sono molto più difficili da scottare rispetto all'altro pollame. Il loro denso piumaggio non è penetrato tanto facilmente dall'acqua, e la facilità con cui sono rimosse le penne sulla coscia non è un indice così accurato della condizione generale. Una pratica comune è avvolgerli in tela da sacchi (vecchi sacchi per granaglie) dopo averli scottati, e permettere loro di esalare vapore nel caldo, bagnate le penne per alcuni minuti prima di cominciare a spennare. Già allora una scottatura supplementare è qualche volta necessaria, dopo che una parte delle penne è stata rimossa. Negli stabilimenti di imballaggio è spesso usato del vapore acqueo per scottare, fornendo una scottatura asciutta. Il vapore usato è talora preso da un tubo o un tubo flessibile, ma si dice che la vaporizzazione diretta sia più soddisfacente. Alcuni dei più piccoli stabilimenti di imballaggio usano un metodo di vaporizzare le anatre che può essere applicato dovunque. Su un tondo comune, una stufa per biancheria da lavare ampiamente ricoperta, è messa una caldaia da bucato con circa 3 o 4 pollici di acqua nel fondo; nella caldaia è una intelaiatura di legno che mantiene l'uccello nel vapore senza permettergli di entrare nell'acqua. L'uccello è messo nella caldaia e vaporizzato per circa 1 o 1,5 minuti su un lato, poi è girato ed è vaporizzato sull'altro lato per la stessa durata di tempo. |

|

|

In picking ducks and geese powdered rosin is sometimes used to assist in removing the fine down left after the outside feathers are removed. The rosin is rubbed onto the down, which mats, and is then more easily removed. |

Nello spennare anatre e oche è talora usata polvere di colofonia per aiutare nel rimuovere il fine piumino rimasto dopo che le penne esterne sono rimosse. La colofonia è strofinata sopra il piumino, che si arruffa, e quindi è rimosso più facilmente. |

|

|

|

||

|

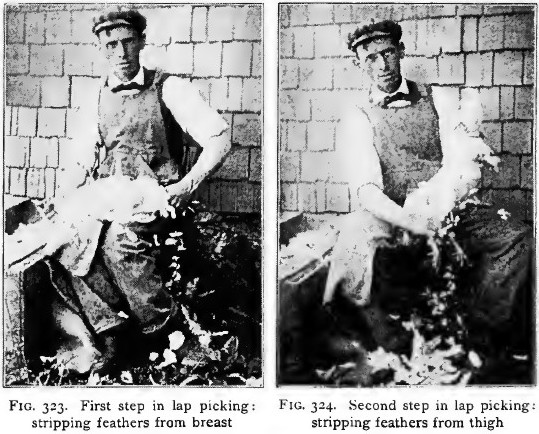

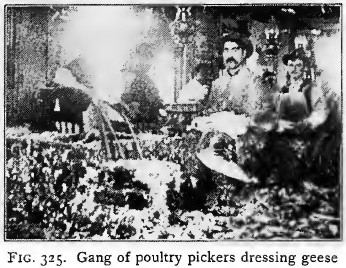

In scald picking the picker usually works standing, with the bird on a table or a bench before him, and rough picks with the hands and the fronts (not the tips) of his thumbs and fingers. Most pickers remove stiff tail and wing feathers first, but some leave them until the last. It makes little difference. The important thing is for the picker to have a systematic way and to pick clean as he goes, except for stubs and pinfeathers, which must be removed one by one. |

Nello spennare scottando di solito il raccoglitore lavora in piedi, con l'uccello su una tavola o una panca di fronte a lui, e rude raccoglie con le mani e le fronti (non le punte) dei suoi pollici e dita. La maggior parte dei raccoglitori per prima cosa rimuove la coda compatta e le piume delle ali, ma alcuni le lasciano sino alla fine. Ciò comporta una piccola differenza. La cosa importante è per il raccoglitore avere una pratica regolare e raccogliere con precisione come lui fa, a parte tronconi e penne nascenti che devono essere rimossi uno alla volta. |

|

|

Dry picking. The removal of the feathers without wetting is the method favored by most eastern markets, and is best adapted to poultry that is to be kept in storage. It may be done at any time after killing. Pigeons and guineas and game birds of all kinds are [217] marketed with the feathers on. In general practice with poultry, however, dry picking is done while the bird is dying, when it has lost consciousness and is insensible to pain, but when the relation between nervous and muscular systems still continues. Good work in dry picking depends first upon the proper sticking of the bird.* |

Raccolta asciutta . La rimozione delle penne senza bagnare è il metodo preferito dalla maggior parte dei mercati orientali, ed è molto adatto per il pollame che deve essere tenuto in magazzino. Può essere fatta in qualunque momento dopo averlo ucciso. Piccioni e faraone e selvaggina di tutti i tipi sono venduti sul mercato con le penne addosso. Tuttavia nella pratica generale con il pollame la raccolta asciutta è fatta mentre l'uccello sta morendo, quando ha perso coscienza ed è insensibile al dolore, ma quando la relazione tra il sistema nervoso e muscolare è ancora attiva. Il buon lavoro nella raccolta asciutta dipende innanzitutto dal corretto bloccaggio dell'uccello.* |

|

|

* The principle upon which this process is based is best explained by reference to a phenomenon which every one with a little experience in handling poultry has had occasion to observe. If in catching a bird one grasps it by the tail, some of the feathers are likely to be pulled out, and if the hold is only on the feathers, the bird will probably escape. If the bird is caught by the thigh, unless the hand quickly closes very tightly on it, a good many feathers may be pulled out just by the action of the closing of the hand on the leg, and by the momentum of the bird. Not infrequently, when caught by the back with so insecure a hold that the person catching it feels that he has hardly more than touched the bird, it loses feathers. Considering how hard these feathers usually are to get out when he wants them removed, the poultry keeper always feels somewhat surprised at the ease with which they come out under these circumstances. There is plainly a direct relation between the mental condition of the bird and the tenacity of the feathers. When the bird is in a state of fright, the feathers loosen, and their loosening may enable the bird to escape. The same effect on the feathers is secured by paralyzing the bird by stunning or by piercing the brain. It is also secured when the bird is killed by dislocating the neck, or by wringing the neck, or by beheading, though in the last two cases the complete severance of the head makes it impossible to direct the flow of blood and begin picking immediately, and so the feathers are relaxed a second time by scalding. |

* Il principio su cui è basato questo processo è molto ben spiegato dal riferimento a un fenomeno che chiunque con una piccola esperienza nel maneggiare il pollame ha avuto occasione di osservare. Se nel prendere un uccello uno lo afferra alla coda, alcune delle penne saranno probabilmente rimosse, e se la presa è solo sulle penne, probabilmente l'uccello scapperà. Se l'uccello è preso alla coscia, a meno che la mano vi si chiuda velocemente in modo molto stretto, parecchie penne possono essere tolte proprio dall'azione della chiusura della mano sulla gamba, e dallo slancio dell'uccello. Non infrequentemente, quando preso alla schiena con una presa così insicura che la persona che lo prende sente che ha solo toccato l'uccello, perde delle penne. Considerando come di solito queste penne sono dure da togliere quando lui le vuole rimosse, l’allevatore di pollame si sente sempre piuttosto sorpreso dalla facilità con cui si distaccano in queste circostanze. C'è chiaramente una relazione diretta tra la condizione mentale dell'uccello e la resistenza delle penne. Quando l'uccello è in uno stato di paura, le penne si allentano, e il loro allentarsi può mettere l'uccello in grado di scappare. Lo stesso effetto sulle penne è assicurato paralizzando l'uccello stordendo o forando il cervello. È anche assicurato quando l'uccello è ucciso slogando il collo, o torcendo il collo, o decapitando, sebbene negli ultimi due casi la separazione completa della testa renda impossibile dirigere il flusso di sangue e cominciare a raccogliere immediatamente, e così le penne sono rilassate una seconda volta scottando. |

|

|

|

||

|

Note. When the sticking is well done, the feathers come off quite as easily as with good scalding, but with a poor stick they come harder, and an inexpert picker is likely to break the skin and perhaps tear the birds badly. As in scald picking, the picker works as much as possible with his hands, wetting them at intervals to make the feathers stick to them, removing the feathers in handfuls, rubbing them off and unless pinfeathers are very small, taking them with the others. The pinfeathers and stubs that are not taken in this way must be removed one by one. For this (in both methods) the professional picker uses a short knife, either seizing the stub between his thumb and the blade, or shaving it off. Practice, and a certain aptitude for such work, are required to [318] make a good, fast picker. Aptitude consists largely in working methodically when removing the feathers, and in picking as clean as possible at every step. As to the division of the work, practice varies largely according to the quality of help to be obtained. Where enough capable pickers can be obtained, each finishes his own bird; where the supply of good pickers is short, the skilled pickers often rough pick the birds and employ less expert persons to remove the stubs and pinfeathers. |

Nota. Quando lo spennare è ben fatto, le penne vengono via davvero tanto facilmente come con una buona scottatura, ma con un povero spennare diventano più dure, e un raccoglitore inesperto è probabile che rompa la pelle e forse laceri male gli uccelli. Come nella raccolta con scottatura, il raccoglitore lavora il più possibile con le sue mani, bagnandole a intervalli per rendervi le penne attaccate, rimuovendo le penne in manciate, strofinandole via e, a meno che le penne nascenti siano molto piccole, prendendole con le altre. Le penne nascenti e i mozziconi che non sono presi in questo modo devono essere rimossi uno per uno. Per questo (in entrambi i metodi) il raccoglitore professionale usa un coltello corto, o afferrando il mozzicone tra il suo pollice e la lama, o radendolo via. La pratica, e una certa attitudine per tale lavoro, sono richiesti per rendere un raccoglitore buono, veloce. L’attitudine consiste grandemente nel lavorare metodicamente quando si rimuovono le penne, e nel raccoglierle il più pulite possibile a ogni fase. A causa della ripartizione del lavoro, la pratica varia grandemente a seconda della qualità di aiuto che deve essere ottenuta. Dove possono essere ottenuti dei raccoglitori abbastanza capaci, ciascuno finisce il suo proprio uccello; dove è scarso il rifornimento di buoni raccoglitori, i raccoglitori qualificati spesso rozzi spennano gli uccelli e usano persone meno competenti per rimuovere i mozziconi e le penne nascenti. |

|

|

Scalding and dry picking compared. After the knack of sticking is acquired, dry picking is often more convenient. Unless the bird is properly killed, it is usually much easier for a novice in picking to get the feathers off by scalding, even if he has to build a fire and wait for the water to heat. In the results of inexpert use of the two methods there is little to choose, but, judging by the comparative scarcity of good scalders, it is much easier to acquire the knack of sticking than to learn to scald right. A poor scalder is apt to disfigure all his birds and, if he has never seen poultry well scalded, to think that it is unavoidable. In dry picking it is not possible to miss seeing the difference in good and poor work, the inexpert picker's great difficulty being to avoid tearing the skin. He can therefore judge his own work better, and with practice is almost sure to become passably expert. Dry-picked poultry is said to keep longer in cold storage than even the best scalded poultry. For use within a few weeks after killing, the advantage of dry picking over good scalding is not apparent. The use of methods, however, is not a matter of choice with the producer who dresses his own poultry. He must follow the custom in his market, and scald pick or dry pick, or perhaps do some of both, according to the disposition to be made of his stock. |

Scottatura e raccolta asciutta messe a confronto . Dopo che l'abilità del bloccaggio è stata acquisita, la raccolta asciutta è spesso più conveniente. A meno che l'uccello sia opportunamente ucciso, di solito per un novizio nel raccogliere è molto più facile togliere le penne scottando, anche se deve creare un fuoco e aspettare che l'acqua si scaldi. Nei risultati dell’uso inesperto dei due metodi c’è poco da scegliere, ma, giudicando dalla relativa scarsità di buone scottatrici, è molto più facile acquisire l'abilità di bloccaggio che imparare a scottare giusto. Un povero scottatore è adatto per deturpare tutti i suoi uccelli e, se lui non ha mai visto pollame ben scottato, per pensare che è inevitabile. Nel raccogliere asciutto non è possibile sbagliare nel vedere la differenza nel buono e nel povero lavoro, la grande difficoltà del raccoglitore inesperto essendo l’evitare di lacerare la pelle. Lui può perciò giudicare meglio il suo proprio lavoro, e con la pratica è quasi sicuro di diventare discretamente esperto. Si dice che il pollame ripulito asciutto resiste più a lungo in un magazzinaggio freddo anche rispetto al pollame meglio scottato. Per un uso entro poche settimane dopo l’uccisione, il vantaggio della raccolta asciutta rispetto a una buona scottatura non è evidente. Comunque, l'uso di metodi non è una questione di scelta col produttore che prepara il suo proprio pollame. Lui deve seguire la consuetudine nel suo mercato, e raccogliere scottato o raccogliere asciutto, o forse farli un po’ ambedue, secondo la disposizione di essere fatto per la sua merce. |

|

|

Market requirements as to picking. The large eastern city markets and pleasure resorts prefer dry-picked poultry. Inland, western, and southern markets, almost without exception, want the poultry for local consumption scald picked; but at many of these points poultry shipped to eastern markets is dry picked. Customs, however, are not consistently governed by the market preference; conditions affecting shipment and the disposition of the goods may determine the method, and the poultry trade presents some striking anomalies in practice at this point. Thus, while the East prefers dry-picked poultry, a large proportion, perhaps the greater part, of the ducks produced there are scalded. Eastern turkeys are often scalded, while western turkeys for the eastern market are mostly dry picked. Poultry from the states in the Mississippi Valley east of the river is often scalded, even by the packers, for the eastern market; while in the states west of the river the poultry going east is all dry picked. The poultry from points nearest the market, reaching it quickly and [319] likely to be consumed at once, is scalded (that being the cheaper method), while that which takes longer to reach the market and is not so likely to find ready sale, and may have to go into cold storage, is dry picked (that being the method which best insures its keeping). |

Richieste di mercato come raccogliere . I grandi mercati orientali di città e i ritrovi di piacere preferiscono il pollame ripulito asciutto. I mercati dell'entroterra, occidentali e meridionali, quasi senza eccezione, vogliono il pollame ripulito scottato per un consumo locale; ma in molti di questi punti il pollame inviato ai mercati orientali è ripulito asciutto. Tuttavia le consuetudini non sono governate costantemente dalla preferenza di mercato; condizioni che influiscono sulla spedizione e sulla sistemazione dei beni possono determinare il metodo, e in pratica a questo punto il commercio del pollame presenta alcune impressionanti anomalie. Così, mentre l'Est preferisce il pollame ripulito asciutto, una grande percentuale, forse la maggior parte delle anatre ivi prodotte è scottata. I tacchini orientali sono spesso scottati, mentre i tacchini occidentali per il mercato orientale hanno quasi sempre una raccolta asciutta. Il pollame dagli stati della Valle del Mississippi a est del fiume spesso è scottato, anche dagli imballatori, per il mercato orientale; mentre negli stati a ovest del fiume il pollame che va a est è tutto ripulito asciutto. Il pollame di punti più vicini al mercato, raggiungendolo rapidamente e probabilmente per essere subito consumato, è scottato (essendo il metodo più a buon mercato), mentre quello che ci impiega di più per raggiungere il mercato e non è molto probabile che trovi una pronta vendita, e può dover andare in un deposito freddo, è ripulito asciutto (essendo il metodo che meglio assicura la sua conservazione). |

|

|

At bottom it is not so much a question of method as of good work by either method. Good poultry marketed in good condition will bring about the same price scalded or dry picked, when the demand is brisk, but when trade is dull, poultry dressed by the method not favored in a market is hard to move on that market. |

Fondamentalmente non è tanto una questione di metodo quanto di buon lavoro con entrambi i metodi. Il buon pollame messo sul mercato in buone condizioni avrà lo stesso prezzo se raccolto scottato o asciutto, quando la richiesta è forte, ma quando l’attività commerciale è fiacca, il pollame preparato con un metodo non favorito in un mercato è duro da gestire su tale mercato. |

|

|

Importance of proper cooling. In respect to its effect on quality, cooling is the most important part of the preparation of poultry for food. Enormous quantities of good poultry are damaged or spoiled entirely because not properly cooled when killed. The object of cooling is to remove the animal heat and check decomposition. The sooner the body is cooled, the longer it will keep and the better will be the texture and flavor of the meat. In cold weather, poultry may be cooled in the air (dry cooled). When the temperature is too high for rapid cooling in the air, poultry is cooled first in water of the ordinary temperature at which it comes from the well or hydrant, and then in ice water. Cooling the warm body suddenly in ice water is less effective than beginning with water of a higher temperature. It is supposed that too rapid chilling at the surface diminishes its conductivity and allows the animal heat inside to start decomposition more actively. Whenever it can be done, dry cooling is preferred to cooling in water. When the days are warm and the nights cool it is usual to put poultry into water in barrels, tubs, or tanks as soon as killed, and at night to hang it up or place it on racks to finish cooling. The killing should always be timed so as to give poultry sufficient time to cool before being packed. When it is to be shipped only a few hundred miles or packed in ice, cooling for a night and a part of a day (according to the time of killing) should be enough. If the poultry is to be shipped dry packed for a long distance, it should be more thoroughly cooled. It is of much more importance that poultry should be well cooled before a long shipment than that it should be started on its journey quickly. The condition of the poultry at the start is a more important factor in its keeping than the time in transit. Packers nearly a week from their market cool poultry two or three days before shipping. |

L'importanza di un corretto raffreddamento . Riguardo al suo effetto sulla qualità, raffreddare è la parte più importante della preparazione del pollame come cibo. Quantità enormi di buon pollame sono del tutto danneggiate o guaste perché non propriamente raffreddate quando uccise. Lo scopo di raffreddare è rimuovere il calore animale e arrestare la decomposizione. Più presto il corpo è raffreddato, più a lungo si conserverà e migliore sarà la struttura e il sapore della carne. Quando fa freddo, il pollame può essere raffreddato all'aria (raffreddato asciutto). Quando la temperatura è troppo alta per un rapido raffreddamento all'aria, il pollame viene prima raffreddato in acqua con temperatura ordinaria che viene dal pozzo o dall’idrante, e poi in acqua con ghiaccio. Raffreddare velocemente il corpo caldo in acqua con ghiaccio è meno efficace che cominciare con acqua di una temperatura più alta. Si suppone che il raffreddare troppo rapidamente alla superficie diminuisce la sua conduttività e permette al calore animale interno di avviare la decomposizione più attivamente. Ogni qualvolta può essere fatto, il raffreddamento asciutto è preferito al raffreddamento in acqua. Quando i giorni sono caldi e le notti fresche si è soliti mettere il pollame appena ucciso in acqua di barili, vasche, o serbatoi, e di notte appenderlo o metterlo su stenditoi per finire il raffreddamento. L'uccisione dovrebbe sempre essere calcolata in modo di dare al pollame tempo sufficiente per raffreddarsi prima di essere impacchettato. Quando deve essere inviato solo per poche centinaia di miglia o riempito di ghiaccio, il raffreddare per una notte e una parte del giorno (a seconda del momento dell’uccisione) dovrebbe essere abbastanza. Se il pollame deve essere inviato impacchettato asciutto per una lunga distanza, dovrebbe essere rinfrescato più completamente. È di molta maggiore importanza che il pollame venga raffreddato bene prima di una lunga spedizione rispetto a quanto si dovrebbe cominciare rapidamente sul suo viaggio. La condizione del pollame all'inizio è un fattore più importante nella sua custodia rispetto al tempo in transito. Gli imballatori a quasi una settimana dal loro mercato raffreddano il pollame 2 o 3 giorni prima di spedirlo. |

|

|

[320] Shaping. The operation of shaping is done sometimes as the birds are cooling, sometimes as they are packed. The object is to make the bird appear as plump as possible. The advantage is greatest with poultry in fair condition but not noticeably well meated. In Europe a number of methods of shaping are practiced, some even going so far as to wrap each bird tightly in cloth while cooling. A more common method there, used to some extent in Canada, is to place the birds in a squatting position in V-shaped troughs, with a weight on the back of each bird. A similar but simpler method is used by some packers in the United States, the birds being held in a squatting position on a rack by strips from 1½ to 2 inches high, about 6 or 8 inches apart in front and coming together at the rear, a board the length of the rack serving as a weight for all the birds on it. With good, plump stock there is little occasion for such shaping for American markets. The object of it is evidently deceptive, ― to press in the breast and hip bones and give an appearance of greater meatiness than exists. Good stock does not need this treatment for these markets. All that is necessary is to pack in such position that the carcass will present a symmetrical appearance and show for just what it is. |

Sagomatura . L'operazione di sagomatura è fatta talora quando gli uccelli stanno raffreddandosi, qualche volta quando sono impacchettati. Lo scopo è far apparire l'uccello il più grassoccio possibile. Il vantaggio è più grande con il pollame in buona condizione ma non bene in carne in modo evidente. In Europa è praticato un quantità di metodi di sagomatura, con alcuni che vanno addirittura tanto a fondo come avvolgere strettamente ogni uccello in stoffa mentre si raffredda. Un metodo più comune, usato in una certa misura in Canada, è mettere gli uccelli in una posizione accovacciata in trogoli con forma a V, con un peso sulla schiena di ogni uccello. Un metodo simile ma più semplice è usato da alcuni imballatori negli Stati Uniti, essendo gli uccelli tenuti in una posizione accovacciata su una rastrelliera con listelli alti da 1½ a 2 pollici, separati da circa 6 o 8 pollici sul davanti e che si uniscono sul retro, un’assicella della lunghezza della rastrelliera che serve come un peso per tutti gli uccelli su di essa. Con del bestiame buono, grassoccio, c’è una piccola occasione per tale sagomatura per i mercati americani. Il suo scopo è evidentemente ingannevole ― pigiare le ossa nel petto e nell’anca e dare un aspetto di maggior carnosità di quella esistente. Un buon bestiame non ha bisogno di questo trattamento per questi mercati. Tutti ciò che è necessario è impacchettare in una posizione tale che la carcassa presenterà un aspetto simmetrico e mostrerà precisamente ciò che è. |

|

|

Grading. The proper sorting and grading of dressed poultry is of less importance to the ordinary producer than to the packer, but still it should have his attention. Packers make many grades, according to weight, quality, condition, etc. Producers marketing their own poultry usually make no more than three grades of any one kind of poultry, ― firsts, seconds, and culls, ― and unless operations have been very unsuccessful, the proportion of seconds and culls should be small. |

Classificazione . La corretta selezione e classificazione di pollame preparato è di minore importanza per il produttore ordinario che per all'imballatore, ma tuttavia dovrebbe avere la sua attenzione. Gli imballatori creano molte categorie, a seconda del peso, della qualità, della condizione ecc. I produttori che mettono sul mercato il loro pollame di solito fanno non più di 3 categorie di ciascun tipo di pollame ― prima, seconda, e scarti ― e, salvo che le operazioni abbiano avuto molto insuccesso, la proporzione di secondi e scarti dovrebbe essere piccola. |

|

|

Firsts are choice, well-finished birds, not damaged in dressing. |

Primi sono uccelli di prima qualità, ben rifiniti, non danneggiati nell’abbigliamento. |

|

|

Seconds are slightly inferior birds, and firsts slightly damaged in dressing. |

Secondi sono uccelli lievemente inferiori e i primi danneggiati leggermente nell’abbigliamento. |

|

|

Culls are decidedly poor and badly damaged birds. |

Scarti sono uccelli nettamente poveri e molto danneggiati. |

|

|

Whether selling single birds to individual consumers or selling in quantity, the poultry keeper should carefully avoid putting inferior stuff with his better grades. The object of grading is not to pass off all that he has with the highest grade that it can get by, but to assort it in conformity with the general scale of prices and demands of the trade. There is nothing to be gained in money by [321] grading poultry too high. There is more likely to be a loss, for the inferior birds packed with those of a better grade detract from the appearance of the lot and often reduce the price. In addition to grading each kind of poultry, the shipper should keep different kinds, though of like quality, separate, and as far as practicable should have each package of birds uniform in size. It is much easier to do this now, when small packages are in vogue, than it was when most poultry was packed in barrels and large boxes. |

Vendendo i singoli uccelli a consumatori individuali o vendendoli in quantità, l’allevatore di pollame dovrebbe attentamente evitare di mettere roba inferiore con le sue categorie migliori. La finalità del classificare è non eliminare tutti quelli che lui ha col grado più alto che può ottenere, ma suddividerlo in conformità alla scala generale di prezzi e richieste dell’azienda. Non c'è niente da essere guadagnato in soldi classificando troppo alto il pollame. È più probabile che ci sia una perdita, in quanto gli uccelli inferiori impacchettati con quelli di un grado migliore sviliscono l'aspetto della partita e spesso riducono il prezzo. Oltre a classificare ogni tipo di pollame, lo spedizioniere dovrebbe tenere i tipi diversi, sebbene di qualità uguale, separati, e per quanto fattibile dovrebbe avere ogni pacco di uccelli di dimensione uniforme. È molto più facile ora fare questo, quando i piccoli pacchi sono di moda, di quando la maggior parte di pollame era impacchettata in barili e in grandi scatole. |

|

|

|

||

|

Packing. Two methods of packing are used, ― dry packing and ice packing, the former being employed when weather and distance permit, and the latter when there is danger of poultry spoiling in transit unless iced. |

Impacchettamento . Sono usati 2 metodi di impacchettamento ― impacchettamento asciutto e impacchettamento con ghiaccio, il primo è usato quando lo permettono il tempo atmosferico e la distanza, e il secondo quando c'è il pericolo che durante il trasporto il pollame si guasti se non è ghiacciato. |

|

|

|

||

|

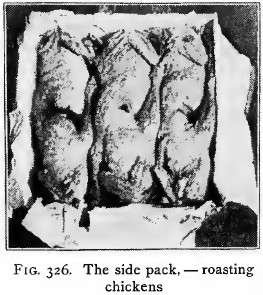

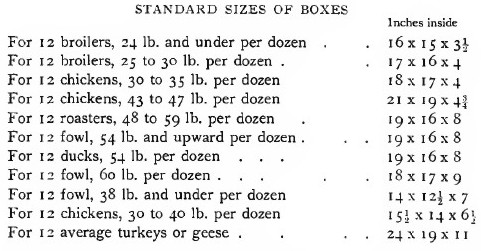

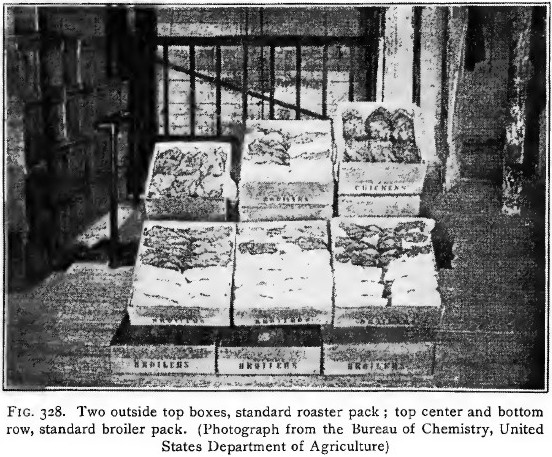

Dry-packed poultry is mostly shipped in boxes. For irregular and small shipments any clean second-hand box of convenient size may be used. For regular shipments of choice poultry it is better to use special boxes holding one or two dozen birds, and of dimensions to suit the sizes of the birds. For regular short-distance shipments (by express) of poultry going into immediate consumption [322] it is best to use returnable boxes very substantially built, with covers held in place with bolts and nuts, and with handles on the ends for convenience in lifting. For long-distance shipments and for lots which it may be desired to hold in storage, such light boxes as the poultry packers use are more suitable. Packers making many grades of poultry and assorting carefully as to size use boxes of different dimensions, to fit one or two dozen birds of each size. The producer will usually find it more satisfactory to use a few standard-sized boxes adapted to the sizes of birds of which he ships most, putting fewer large birds, and a large number of small ones, in a box. While the dozen is a convenient numerical division, poultry nearly always is sold by weight* and even when the trade prefers one- or two-dozen lots, an occasional package containing less or more than the round number will sell as readily as the rest. Styles of box packing are shown in Figs. 326-328. |

Il pollame impacchettato asciutto è inviato soprattutto in scatole. Per spedizioni non regolari e piccole può essere usata qualunque scatola pulita di seconda mano e di volume conveniente. Per spedizioni regolari di pollame di prima qualità è meglio usare scatole speciali che contengono una o due dozzine di uccelli, e di dimensioni tali da essere adatte alle dimensioni degli uccelli. Per spedizioni regolari a breve distanza (per espresso) di pollame di consumo immediato è meglio usare scatole da restituire, costruite in modo molto solido, con coperchi tenuti fermi con bulloni e dadi, e con manici alle estremità per comodità nell'alzarle. Per spedizioni a lunghe distanze e per partite che si può desiderare di tenere in deposito, le scatole leggere come usano gli impacchettatori di pollame sono più appropriate. Gli impacchettatori, realizzando molte categorie di pollame e suddividendolo attentamente in base alle dimensioni, usano scatole di dimensioni diverse, per preparare una o due dozzine di uccelli di ogni grandezza. Il produttore troverà di solito più soddisfacente usare alcune scatole di dimensioni standard adattate alle dimensioni degli uccelli dei quali spedisce la maggior parte, mettendo meno grandi uccelli, e un grande numero di piccoli, in una scatola. Mentre la dozzina è una suddivisione numerica conveniente, il pollame è quasi sempre venduto in base al peso*, e anche quando la clientela preferisce una o due dozzine di partite, un pacco occasionale che contiene meno o più del numero intero si venderà prontamente come il resto. Forme di scatola per impacchettare sono mostrate nelle figure 326-328. |

|

|

* There are a few places where birds are sold at so much apiece, or so much a dozen, without regard to weight. |

* Ci sono alcuni luoghi dove gli uccelli sono venduti a così tanto ognuno, o a così tanto alla dozzina, senza considerazione per il peso. |

|

|

|

||

|

Boxes for the smallest birds may be made of 1/4-inch stuff for sides, and ½-inch for ends; boxes for birds of medium weight, of 3/8 inch stuff for sides and 5/8 inch for ends; those for heavy-weight birds, of ½ inch stuff for sides and 7/8 inch for ends. If many boxes are needed, it will pay to buy regulation sizes in knockdown bundles, or, if there is a box factory near to have stuff got out to measure there and put it together as wanted. Sometimes empty packing cases of suitable material can be bought so cheap that the poultryman can afford to cut them up and make his own packing boxes at odd times. |

Scatole per uccelli molto piccoli possono essere costituite con lati di un materiale di ¼ di pollice, e ½ pollice per le estremità; scatole per uccelli di peso medio, con lati di un materiale di 3/8 di pollice e 5/8 di pollice per le estremità; quelle per uccelli assai pesanti, con lati di un materiale di ½ pollice e 7/8 di pollice per le estremità. Se si ha bisogno di molte scatole, si pagherà per comprare dimensioni regolamentari in gruppi in ribasso, o, se c'è una fabbrica di scatole vicina, avere materiale fuori misura e metterlo insieme come voluto. Qualche volta casse di imballaggio vuote di materiale appropriato possono essere comprate così a buon prezzo che l’avicoltore può permettersi di tagliarle e fabbricare le sue scatole di impacchettamento quando capita. |

|

|

[323] There are two principal points to be observed in packing: (1) that the birds be packed solidly, so that they will not shift when the package is handled; (2) that the package, when opened, present an orderly arrangement and show the goods to advantage. The removal of the cover should show either all breasts, all backs, or all sides, and legs, heads, and wings all in the same relative positions. |

Ci sono due punti principali da osservare nell'impacchettare: (1) che gli uccelli siano impacchettati per bene, cosicché non saranno spostati quando il pacco è maneggiato; (2) che il pacco, quando aperto, presenti una sistemazione ordinata e mostri i beni in posizione di vantaggio. La rimozione del coperchio dovrebbe mostrare o tutti i petti, tutte le schiene, o tutti i lati, e gambe, teste e ali tutte nelle stesse posizioni relative. |

|

|

|

||

|

Ice-packed poultry is usually shipped in large barrels. A layer of clean chipped ice is first placed on the bottom of the barrel, then a layer of poultry, packed in a circle with backs up and feet toward the center, the poultry nowhere touching the sides of the barrel; then a layer of ice and another layer of poultry, and so on until the barrel is full to within six inches of the top, when it is filled with larger pieces of ice and covered with bagging. In very warm weather a large chunk of ice put on top (under the bagging) will add to the safety of the shipment. Poultry thoroughly cooled before packing, and properly packed and iced, should be safe for two days' shipment by express or for four or five days [324] in a refrigerator car. Natural ice is better for packing poultry than artificial ice, because it melts faster, and the cold water percolating through the layers of poultry keeps them at a uniformly cool temperature. If the ice melts too slowly, the poultry may arrive at its destination in poorer condition with much ice remaining than if the ice has all melted. |

Pollame impacchettato con ghiaccio è di solito inviato in grandi barili. Uno strato di ghiaccio pulito tagliato a pezzi è dapprima messo sul fondo del barile, poi uno strato di pollame impacchettato in cerchio con le schiene in alto e i piedi verso il centro, con il pollame che in nessun punto tocca i lati del barile; poi uno strato di ghiaccio e un altro strato di pollame, e così via finché il barile è pieno fino a 6 pollici dalla cima, quando è riempito con pezzi più grandi di ghiaccio e coperto con tela da sacchi. Quando fa molto caldo un grande pezzo di ghiaccio messo in cima (sotto la tela da sacchi) aggiungerà sicurezza alla spedizione. Pollame assai raffreddato prima di impacchettare, e opportunamente impacchettato e ghiacciato, dovrebbe essere al sicuro per una spedizione di 2 giorni con un corriere espresso o per 4 o 5 giorni in una carrozza frigorifero. Il ghiaccio naturale è migliore per impacchettare il pollame rispetto al ghiaccio artificiale, perché si liquefa più velocemente, e l'acqua fredda che cola attraverso gli strati di pollame li mantiene a una temperatura uniformemente fresca. Se il ghiaccio si liquefa troppo lentamente, il pollame può arrivare alla sua destinazione in condizioni più povere con molto ghiaccio che residua anziché essersi del tutto liquefatto. |

|

|

Feathers. Wherever a considerable quantity of poultry is dressed it will pay to save and sell the feathers. The feathers of ducks and geese, if handled and disposed of properly, should pay for the picking. Other feathers are less valuable but still worth taking care of. Stiff and soft feathers, white and colored feathers, and the feathers of each kind of poultry should be kept separate. The feathers from dry-picked stock are usually in better condition than those from scalded stock, but with a little care scalded feathers can be cured so that they will sell well, though not as prime feathers. The wing and tail feathers require no curing; the body feathers should be placed in bins or in a loft and forked over at intervals until the quills are thoroughly dry. |

Piume . Per qualsiasi scopo una quantità considerevole di pollame è adorna, pagherà per salvare e vendere le piume. Le piume di anatre e oche, se maneggiate e correttamente disposte, dovrebbero ripagare per la raccolta. Le altre piume sono meno preziose ma vale ancora la pena prendersene cura. Le piume rigide e molli, le piume bianche e colorate, e le piume di ogni tipo di pollame, dovrebbero essere tenute separate. Le piume raccolte asciutte sono di solito in condizioni migliori di quelle scottate, ma con una piccola cura le piume scottate possono essere conservate in modo che saranno vendute bene, sebbene non come prime piume. Le piume dell'ala e della coda non richiedono di essere conservate; le piume del corpo dovrebbero essere messe in bidoni o in una soffitta e rigirate a intervalli finché i calami sono completamente asciutti. |

|

|

Shipping live poultry. Ventilated coops with solid bottoms and open sides and tops, made of slats or wire netting over a frame, are used for shipping live poultry. Standard coops used by large shippers are made of hardwood strips reënforced with twisted wire, ― for fowls, 2x3 feet, 12 inches high; for turkeys, 2x3 feet, 16 inches high. A coop with a 2x3 feet bottom is large enough for a dozen medium-sized fowls, and for from one to two dozen chickens, according to size. Filled with live poultry it makes as large and as heavy a package as can be easily handled by one man. This is the size preferred by commission men and expressmen; but many shippers make a larger coop, with floor from 30 to 36 inches wide by 4 feet long, usually with a partition in the middle. These coops are usually homemade. Poultry is not often shipped in coop lots over distances so great that the birds must be fed and watered in transit. Long-distance shipments are usually made by middlemen either in cars especially fitted for poultry, or with an attendant to feed and water on the journey. |

Spedizione di pollame vivo . Stie ventilate con fondi solidi e lati e cime aperti, fatte di assicelle o rete metallica sopra un’intelaiatura, sono usate per inviare pollame vivo. Stie standard usate dai grandi spedizionieri marittimi sono fatte di listelli di legno duro rinforzati con filo metallico ritorto ― per polli, 2x3 piedi, altezza 12 pollici; per tacchini, 2x3 piedi, altezza 16 pollici. Una stia con un fondo di 2x3 piedi è grande abbastanza per una dozzina di uccelli di media grandezza, e per una fino a due dozzine di polli, a seconda delle dimensioni. Riempita con pollame vivo costituisce un pacco grande e pesante da essere maneggiato facilmente da un uomo. Questa è la dimensione preferita da uomini di commissione e da corrieri veloci; ma molti spedizionieri marittimi fanno una stia più grande, con un pavimento largo da 30 a 36 pollici e lungo 4 piedi, di solito con un tramezzo al centro. Queste stie sono di solito fatte in casa. Il pollame spesso non è inviato in un gran numero di stie su distanze così grandi che gli uccelli devono essere alimentati e ricevere da bere durante il trasporto. Spedizioni a lunga distanza di solito sono fatte da mediatori o in macchine specialmente equipaggiate per il pollame, oppure con un assistente per alimentare e dar da bere durante il viaggio. |

|

|

Sorting and grading. Uniformity is as important with live as with dressed poultry. The birds shipped in a coop (or in a compartment of a double coop) should be of the same kind and as [325] nearly as possible of the same age, size, and weight. It is also an advantage to have them of the same color, for, while color is not of such importance in market as in fancy poultry, as far as it contributes to uniformity of appearance it makes a lot more salable, and often brings a little better price. In general it is advisable to have each lot of the same sex, ― especially in fowls past broiler size. Grading is less essential when shipping to buyers who dress to sell than when shipping to firms which sell the birds alive. Concerns dressing poultry and buying direct from producers will usually sort mixed lots as they kill and make returns accordingly. |

Classificazione e selezione . L'uniformità è tanto importante per il pollame sia vivo che preparato. Gli uccelli spediti in una stia (o in uno scompartimento con una duplice stia) dovrebbero essere dello stesso tipo e per quanto possibile della stessa età, taglia e peso. È anche un vantaggio averli dello stesso colore, in quanto, mentre il colore non è di tale importanza in un mercato come in un pollame di razza, quanto più contribuisce all'uniformità dell’aspetto rende un gruppo più vendibile, e spesso comporta un prezzo lievemente migliore. In generale è consigliabile avere ogni gruppo dello stesso sesso ― specialmente in polli oltre le dimensioni da fare alla griglia. Selezionare è meno essenziale quando si spedisce ad acquirenti che addobbano per vendere anziché quando si spedisce a ditte che vendono gli uccelli vivi. Preoccupazioni di preparare il pollame e comprarlo direttamente dai produttori di solito selezioneranno una gran quantità mescolata come loro uccidono e fanno quindi dei profitti. |

|

|

Eggs. The preparation of eggs for market is the simplest of matters. They must be whole, clean, assorted for color and size, and packed in packages of suitable size. As marketed by a producer they should always be fresh. If a poultry keeper wishes, either for experiment or for home use, to preserve eggs, that is solely his own affair. If he undertakes to sell at the same time preserved and fresh eggs, he will soon find that all his eggs are under suspicion and that he has damaged his best trade. The poultry keeper who wants to make a reputation for good eggs, and to get the highest prices, should keep rigidly to the practice of selling only fresh eggs. |

Uova . La preparazione di uova per il mercato è la più semplice delle questioni. Devono essere intere, pulite, suddivise per colore e grandezza, e impacchettate in confezioni di dimensioni appropriate. Dato che sono introdotte sul mercato da un produttore, dovrebbero essere sempre fresche. Se un allevatore di pollame desidera, o per esperimento o per consumo casalingo, conservare delle uova, è soltanto una sua questione personale. Se intraprende la vendita alla stesso tempo di uova conservate e fresche, presto troverà che tutte le sue uova sono sotto sospetto e che lui ha danneggiato il suo miglior mestiere. L’allevatore di pollame che vuole creare una fama per delle uova buone, e ottenere i prezzi più alti, dovrebbe dedicarsi rigidamente alla pratica di vendere solo uova fresche. |

|

|

Cleaning eggs. If the poultry houses are clean, the nests kept in good condition, and the hens laying eggs with good shells, the proportion of eggs requiring cleaning before being marketed should be small. As far as possible, wetting the shell is to be avoided, for it destroys the "bloom" which is the conspicuous, distinguishing feature of the fresh egg, disappearing with age and handling. If an egg is only slightly soiled it may sometimes be cleaned by rubbing lightly with a dry cloth. If this does not answer, a slightly moistened cloth may remove the dirt. Eggs that are badly soiled should be washed in warm (not hot) water, and dried at once with a soft cloth. The warm water removes the dirt more quickly than cold, and eggs washed in warm water are more easily dried. No soap or other cleansing preparation should be used, ― only clean water. If the shell is stained, as sometimes it is, with manure or from being wet in the nest, it is better to keep the egg for home cooking. It is not injured except in appearance, but it is salable only as a "dirty" at about half price. |

Pulizia delle uova . Se le case del pollame sono pulite, i nidi tenuti in buone condizioni, e le galline depongono uova con dei buoni gusci, la percentuale di uova che richiedono la pulizia prima di essere messe sul mercato dovrebbe essere piccola. Per quanto possibile si eviterà di bagnare il guscio, in quanto distrugge lo "splendore" che è l'evidente, peculiare caratteristica dell'uovo fresco, che scompare con l’invecchiamento e maneggiandolo. Se un uovo è solo leggermente sporco può talora essere pulito strofinandolo leggermente con un panno asciutto. Se questo non dà risultati, un panno leggermente inumidito può rimuovere lo sporco. Le uova che sono assai sporche dovrebbero essere lavate in acqua calda (non molto calda), e subito asciugate con un panno morbido. L’acqua calda rimuove lo sporco più rapidamente di quella fredda, e le uova lavate in acqua calda si asciugano più facilmente. Nessun sapone o altra preparazione detergente si dovrebbe usare ― solo acqua pulita. Se il guscio è macchiato, come talora lo è, dal letame o dall'essere bagnato nel nido, è meglio tenere l'uovo per la cucina di casa. Non è danneggiato eccetto che nell’aspetto, ma è vendibile solo come uno "sporco" a circa metà prezzo. |

|

|

[326] Sorting eggs for color. Uniformity in the color of the shell is desirable, even though the market has not a color preference. Mixed lots of eggs do not look as well or sell as readily as lots of uniform color. Eggs are classed according to color, as white, gray, and brown. |

Suddivisione delle uova in base al colore . L'uniformità nel colore del guscio è desiderabile, anche se il mercato non ha una preferenza di colore. Gruppi di uova mescolate non si presentano bene o non si vendono prontamente come i gruppi di colore uguale. Le uova sono classificate secondo il colore, cioè bianco, grigio e marrone. |

|

|

White eggs are not, as a rule, of a dead-white color, though that is sometimes found; they are nearly always slightly tinted. Eggs that are uniform in color and look white unless closely compared with something whiter may be classed as white. |

Le uova bianche non sono, come regola, di un colore bianco spento, sebbene qualche volta sia rinvenuto; sono quasi sempre leggermente tinte. Le uova che sono di colore uniforme e appaiono bianche, a meno che strettamente paragonate con qualcosa di più bianco, possono essere classificate come bianche. |

|

|

Gray eggs are eggs that are plainly not white, yet not dark enough to be considered brown. The color of the shell usually tends toward black rather than toward red or brown, but extremely light-brown eggs may be classed as gray. |

Le uova grigie sono uova che non sono chiaramente bianche, ma non abbastanza scure da essere considerate marroni. Il colore del guscio di solito tende verso il nero piuttosto che verso il rosso o il marrone, ma uova estremamente marrone chiaro possono essere classificate come grigie. |

|

|

Brown eggs exhibit a wide range of color, from a light, golden brown to a reddish chocolate. Ordinary brown eggs are light brown. What are known to the trade as dark-brown eggs are mostly medium in the range of shades of brown found in eggs. Very dark-brown eggs are comparatively rare and are not often seen in quantity. Commercially, the darkest-brown eggs are not favored beyond the ordinary dark brown eggs. Where the range of shades is so wide the uniformity of color presented by ordinary white eggs graded with a little care can be secured only by a more discriminating selection than it is usually practicable to make. For all ordinary trade purposes it is enough to make two grades of brown eggs, light and dark (medium), discarding, as not brown, the white or gray eggs sometimes laid by brown-egg stock, and packing the darkest eggs with the medium. An appearance of greater uniformity of color may be secured by a little care in placing the eggs so that those of different shades are not placed at random but arranged according to shade, ― not so accurately that the shades blend perfectly, but with care to avoid marked differences in shades of eggs in adjoining compartments. |

Le uova marroni mostrano un’ampia serie di colori, da un chiaro marrone dorato a un cioccolato rossastro. Le comuni uova marroni sono marrone chiaro. Quelle che sono note ai commercianti come uova marrone scuro sono per lo più a metà della gamma di gradazione marrone trovata nelle uova. Uova molto marrone scuro sono relativamente rare e spesso non si vedono in abbondanza. Commercialmente, le uova assai marrone scuro non sono favorite più delle ordinarie uova marrone scuro. Dove la gradazione di tonalità è così ampia, l'uniformità di colore presentata da uova bianche selezionate con una piccola cura può essere assicurata solo da una selezione più fine di quella che è di solito facile fare. Per tutti gli scopi commerciali è sufficiente fare due gradazioni di uova marroni, chiare e scure (medie), scartando, come non marroni, le uova bianche o grigie qualche volta deposte da un gruppo dalle uova marroni, e imballando le uova più scure con le medie. Un aspetto della più grande uniformità di colore può essere assicurato da una piccola cura nel mettere le uova in modo tale che quelle di gradazioni diverse non sono messe a caso ma sistemate a seconda della gradazione ― non così accuratamente che le gradazioni si mescolino perfettamente, ma con cura per evitare marcate differenze in gradazioni delle uova in compartimenti adiacenti. |

|

|

Grading for size. Grading for size consists principally in discarding from lots designed for ordinary trade all very large and all very small eggs. The compartments of boxes and cases used for packing eggs for market are usually of pasteboard sufficiently elastic to allow the larger eggs to spread the sides of the compartment, the smaller eggs being placed in the adjoining compartments; but [327] eggs that are so long that they project above the filler are almost sure to be broken, because the board between the layers of eggs is less elastic and because, when the lower layer is covered, it is not possible to adapt short eggs in one layer to long ones in the one below. Eggs that are too long for the fillers should not be packed in them. A distinction should, however, be made between a long egg of ordinary width which cannot be placed so that its end will not project from its compartment, and a long, narrow egg which will fit diagonally into the compartment. Of eggs that are too wide for the compartments, as many may be used as can be put in without danger to those in adjacent compartments. Provided the shell is strong, an egg of suitable size need not be discarded for any of the common eccentricities of shape, as corrugated shell or marked departure from the oval form. |

Selezione in base alle dimensioni . La selezione in base alle dimensioni consiste principalmente nello scartare dalle partite destinate a un commercio abituale tutte le uova molto grandi e molto piccole. I compartimenti di scatole e scatoloni usati per imballare le uova per il mercato sono di solito di cartone sufficientemente elastico da permettere alle uova più grandi di distendere i lati dello scompartimento, le uova più piccole essendo messe negli scompartimenti adiacenti; ma le uova che sono così lunghe da spingere in alto il riempitivo è quasi sicuro che si romperanno, perché la tavola tra gli strati di uova è meno elastica e perché, quando lo strato più basso è coperto, non è possibile adattare le uova corte di un strato a quelle lunghe di quello sotto. Uova che sono troppo lunghe per i riempitivi non dovrebbero esservi impaccate. Comunque, una distinzione dovrebbe essere fatta tra un uovo lungo di larghezza ordinaria che non può essere messo in modo tale che la sua estremità non si spinga fuori dal suo scompartimento, e un uovo lungo, stretto, che andrà bene diagonalmente nello scompartimento. Di uova troppo larghe per gli scompartimenti se ne possono usare tante quante possono esservi messe senza pericolo per quelle degli scompartimenti adiacenti. Purché il guscio sia forte, un uovo di dimensione appropriata non ha bisogno di essere scartato per alcuna delle comuni eccentricità di forma, come guscio corrugato o marcata devianza dalla forma ovale. |

|

|