Indagine conoscitiva

e anonima

sul luogo d’origine della Cavia

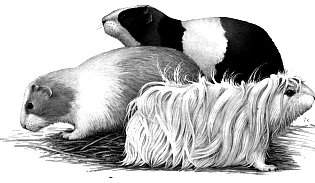

La Cavia

domestica, Cavia aperea porcellus,

appartiene all’Ordine dei Roditori. Insieme a Ratti, Conigli e Topi,

questo animale si è rivelato insostituibile nelle ricerche mediche,

mostrando tra l’altro una risposta ai farmaci praticamente sovrapponibile

a quella dell’Uomo.

In italiano

la Cavia è anche denominata Porcellino

d’India, mentre in inglese è detta Guinea Pig, cioè porcellino della

Guinea, e in russo viene chiamata Marskàia

Svìnka -

Marskàia

= mare -

Svìnka = maiale, equivalente al

tedesco Meerschweinchen

[1]

.

Secondo

le tue conoscenze, di quale degli Stati sottoelencati è originaria?

Bada

bene che una sola delle risposte è quella esatta

Grazie per apporre una croce davanti

alla risposta prescelta.

Canada

Guinea

Bissau

Guinea

Equatoriale

India

Indonesia

Messico

Mongolia

Nuova

Zelanda

Papua-Nuova

Guinea

Perù

A scopo statistico è opportuno

conoscere il tuo titolo di studio:

Media

inferiore

Media

superiore

Università

Grazie della collaborazione.

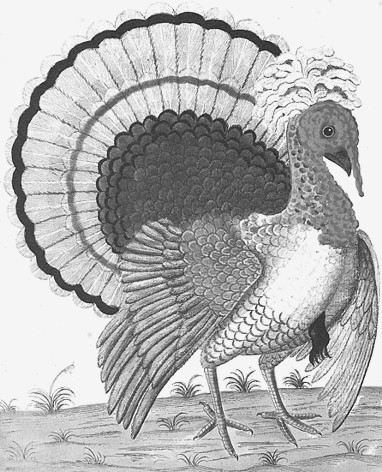

I dati serviranno per una disquisizione di linguistica riguardante l’origine del tacchino.

La Cavia e il Tacchino

Ho approfittato della vostra pazienza per raccogliere un dato per me molto importante: scoprire quanti, come me, pensavano che la cavia fosse di tutt’altra origine meno che sudamericana.

Confesso che nel leggere i vari testi in inglese riguardanti le melanine - quei pigmenti che, oltre a colorare i nostri capelli e i nostri occhi, sono capaci di determinare la variopinta tavolozza dell’abito dei polli - mi trovai frequentemente alle prese con il Guinea-pig, termine usato dagli anglofoni per denominare la cavia. Per un po’ riuscivo a tenere a mente quest’equivalenza, poi me ne dimenticavo perché non riuscivo a collimare l’India con la Guinea. Non riuscivo a capire come mai il nostro porcellino d’India, che chiaramente era originario dell’India, per gli anglofoni fosse originario della Guinea.

Per la Faraona il problema etimologico era più semplice, in quanto, se gli inglesi la denominano Guinea-fowl e i Portoghesi Galinha d’Angola, la discrepanza geografica della terra d’origine non è poi così enorme. In Angola tutt’oggi si parla portoghese, e la Faraona attualmente allevata in Europa deve la sua origine a quella dell’Africa occidentale, la Numida meleagris galeata, che ha le caruncole rosse. Noi continuiamo a chiamarla Gallina del Faraone, ma questo termine è più corretto se viene riservato a quel volatile che è proprio dell’Africa orientale, noto agli antichi Greci, e che aveva caruncole azzurre, la sottospecie Numida meleagris meleagris.

Veniamo alla mia indagine anonima sul paese d’origine della cavia. Sono dell’avviso che il lessico sa trarci in inganno. Infatti, rimasi stupito come un bambino di fronte a Superman, quando, nell’estate di quest’anno, capitai involontariamente sulla cavia, mentre sfogliavo uno dei volumi sulla vita degli animali di Grzimek alla ricerca di tutt’altro. La cavia era di origine peruviana, e gli Inca, quando arrivarono gli Spagnoli nel 1532, ce l’avevano per casa, e se la mangiavano, non so se lessa o arrosto. Mi dissi: che ignorante! Sei stato seduto per un lustro e un quinto sui banchi della facoltà di medicina e nessuno ti ha mai detto che la cavia non è indiana, bensì amerinda! Beh, cerchiamo di non colpevolizzare troppo gli insegnanti, in quanto neppure tu ti sei mai peritato di chiederti di quale parte dell’India fosse, se fosse un roditore di montagna o di pianura. Sta di fatto che, la cavia, peruana è. Non c’è dubbio.

Adesso vediamo come tacchino e cavia possano andare a braccetto. Il tacchino è detto Turkey in inglese, in russo suona Indiùk, Dindon in francese, Kalakùtas in lituano, Pavo in castigliano, Peru in portoghese (Perua è la femmina), Meleagris gallopavo è il termine scientifico del tacchino che fu progenitore di quelli che ci deliziano il palato.

Come potete vedere, il tacchino ha ricevuto diversi nomi, ai quali sottendono problemi non solo etimologici, ma anche storici. Lo stesso potrebbe dirsi del mais, che dà l’olio di semi Maya - non ricevo tangenti dalla Ditta produttrice - e noi chiamiamo comunemente il frutto della Zea mays col nome di granoturco.

Cos’è che mi ha fatto scattare la molla di mettermi alla caccia del significato recondito di alcuni modi in cui è denominato il tacchino? É stato il seguente brano, tratto da un libro stampato a Pavia nel 1789, Praecepta diaetetica, scritto da un mio collega, Gottlob Richter, probabilmente di Gottinga, che fu anche Archiatra del Re d’Inghilterra. Parlando dell’impiego terapeutico dei volatili, a un certo punto dice:

Gallos Indicos, seu calecutenses (Welscher Hahn) quos ex India (seu novo orbe) alii ex Numidia primum venisse volunt: horum pulli duorum aut trium mensium tenerrimi, saporis suavissimi, digestionis promptissimae, multique et boni alimenti sunt. Galli hisque umidiores gallinae, si iuniores sint, vel mediae aetatis et aliquot diebus ante coenam in aëre suspendantur, carnem dant pariter sapidam, teneram, coctu facilem, largumque et durabile alimentum, vires refocillans, omni aetate et sexui congruens, nec sapore nec succi probitate ipsis capis cedens. Veterum gallorum durior caro aegre subigitur.

Gottlob Richter non aveva mai visto né un tacchino né una faraona, né il tacchino l’aveva mai visto il grande Ulisse Aldrovandi, e neppure il grandissimo Pierre Belon. Eravamo, negli ultimi due casi, agli albori dell’arrivo in Europa di questo volatile americano, la cui data parrebbe fissata per il 1511-1512. Ma Richter è un po’ più tardivo, e di un bel po’. Eppure non lo conosceva, come non conosceva la faraona. Altrimenti non avrebbe confuso i due animali.

Interessante, però, quell’aggettivo calecutenses, mi dissi. Perché Calcutta? Poi scoprii che era Calicut la città incriminata di fornire tacchini. Poi venni a sapere che in lituano il tacchino è detto kalakùtas, e che l’olandese kalkoen ha la stessa etimologia del lituano.

A questo punto bisogna vedere come scrivere la storia, se fu Colombo a portare il tacchino in Europa o se vi era giunto in altri tempi e battendo altre vie. Gli scienziati manco vogliono sentir parlare di parole. Essi vogliono ossa da datare col radiocarbonio, ma queste ossa, di un supposto tacchino europeo precolombiano, sono andate al rogo durante l’incendio del Museo di Budapest per motivi bellici.

Una ridda di spunti. Spero che qualcuno di voi segua questa traccia e, un giorno, possa dire la sua in proposito. Così, invece che transatlantico, cominceremo a denominare una grossa nave transpacifico.

Ovviamente, quando il numero di questionari sarà statisticamente significativo, vi comunicherò per filo e per segno i valori elaborati. Per ora posso dirvi che ho ragione, come vedete dalla schedina coi risultati parziali, che include anche le vostre risposte.

E, altrettanta ragione, potrebbero avere coloro che ritengono che il Gallo d’India, il Dindon dei Francesi, l’Indiùk dei Russi, sia giunto in Europa via Asia, via Calicut. Quindi, d’India, ma quella vera. Non amerindo, come la cavia.

Alla data dell'1-12-1996

il quesito è stato posto a 437 persone

Le

risposte sono così suddivise

|

Stato |

totale |

Elementari |

Media |

Media |

Università |

|

Canada |

15 |

0 |

4 |

8 |

3 |

|

Guinea Bissau |

29 |

1 |

13 |

15 |

0 |

|

Guinea Equatoriale |

55 |

0 |

25 |

24 |

6 |

|

India |

122 |

0 |

60 |

54 |

8 |

|

Indonesia |

27 |

1 |

8 |

13 |

5 |

|

Messico |

20 |

0 |

6 |

12 |

2 |

|

Mongolia |

15 |

1 |

1 |

13 |

0 |

|

Nuova Zelanda |

14 |

0 |

5 |

7 |

2 |

|

Papua-Nuova Guinea |

52 |

0 |

10 |

40 |

2 |

|

Perù |

87 |

5 |

17 |

52 |

13 |

|

Respondentes |

436

|

8

|

149

|

238

|

41

|

[1] Il nome tedesco e russo deriverebbe dal comportamento: quando il gruppo di animali diventa eccessivamente numeroso, una quota di individui si autoelimina gettandosi in acqua.

Gallos calecutenses

Kalakùtas - Kalkoen - Peru

From letters to Dr Edmund Hoffmann  and

Prof Roy Crawford - Canada

and

Prof Roy Crawford - Canada

26-1-1996

Now, a little problem about which I desire your ideas. I think that you are competent not only in Muscovy duck (as your superlative job demonstrates) but even in other problems regarding animals as turkey.

In this moment it’s open

a bridge Valenza-Paris-Lisboa about the etymology of the word peru as is called the turkey in Portuguese - only by this word - and

the female is perua. My thesis would

demonstrate that the Portugueses called the turkey Ave do Peru, may be in contraposition of the Spaniards, who called

it Pavo. My thesis arises from the

affirmation reported in Crawford’s book:

“Schorger (1966) states

that they (turkeys) were present in Peru before arrival of the Spanish and may

have be taken there from Nicaragua.”

Do you agree with Schorger?

I don’t know his works, and I think that it’s a little difficult for me to find them. I am also studying the history of the Amazonas conquest by the Portugueses. They were in Peru, in Quito, now Ecuador, in 1637, when Teixeira overstepped the Tordesilla’s line.

The presence of the word peru in India, in Dravidian language, is too much easy to explain: Goa was Portuguese. Interesting also the true possibility of the arrival of the turkeys via Asia. As you can read in Latin (from the ancient book I have, printed in Pavia, Ticinum in Latin, because of its river), the turkey was called Gallos indicos, seu calecutenses. Calecutenses not from Calcutta in Bangladesh, but from Calicut (today also called Kozhicode - 420,000 inh.), near Goa, Kerala State.

If you

agree with Schorger, then peru for turkey arises from Peru. It would be easier for the

Portugueses to call the turkey Mexican bird, Spanish bird. They called it peru.

Each nation called the birds in different ways: Numida

meleagris

is Guinea fowl in English, Galinha d’Angola

em Portuguese, Faraona

(note the abbreviation, right is Gallina

del Faraone) in Italian. And Faraona, is not the wife of the Faraon, but

it’s implied the word Gallina del,

Hen of the etc.

The same is for peru, which was Ave do Peru.

But, when the

turkey was called peru?

Because I think that the Portugueses knew this bird the first time in Europe,

when Colombo or others took it in Spain. Why the Portugueses preferred peru? In the beginning of 1500

they don’t was in Peru, but only in 1637.

Note the big confusion

about the birds’ names in 1779:

Gallos indicos......alii ex

Numidia primum venisse volunt

others tell that the first

time these cocks came from Numidia.

But, Numidia is the land of

Guinea fowl!

Right is this German Archiatra of the King of England, Georg Gottlob, when he tells about India:

quos ex India (seu novo orbe) i.e. or from the New World.

This

annotation and specification is a clear contraposition to calecutenses, because Calicut is in India, the old India, the true

India. The German Welscher

Hahn is most generic, because it means Foreign fowl. This welscher

may becoming from anywhere.

Yesterday, when I was in

Pavia, 58 km from Valenza, to enter in the first touch with the Editor, I

found a very interesting thing: in Lithuania the turkey is called Kalakùtas. Obviously, from Calicut. The Professor who gave me

the information told also that the Lithuanian language is an old interesting

language, i.e. Indo-European of Baltic group.

5-3-1996

Very interesting your

meditation on the use of pavo by

Portuguese Intelligentsia. I hope that, when you will be in possess of the

Schorger book, it will be possible to go in depth of this problem, because I

am collecting a dossier on the

argument, and may be a day it could arise a job with your collaboration,

because I saw that you are very interested in the field. Yes, may be that

Belon was referring to the Old World regarding Coq d’Indie, but I think that

the turkey was already in Europe in 1555 (Italy - 1520, France - 1538).

If you note, in the Gottlob’s

text there is a big confusion:

Gallos indicos

(Coq d’Indie of Bellon),

today Dindon in French (= d’Indon,

d’Indie). Dindo even in some part

of Italy, near Torino for example. Gallos indicos may mean Guinea fowls, because in the past time also

the Abissinia was called India (I don’t remember when and where I had this

notice).

seu calecutenses

or from Calicut

This second name is given

by Gottlob as a current name to indicate the gallos indicos, not as dubitative. This second name is alternative

as in the following phrase, Gallus

gallus or Red Junglefowl. The

Latins don’t had this adjective, calecutensis,

(checked in Latin Dictionary, Georges, 1957) and so I think that this country

was unknown to the Romans.

quos ex India (seu novo

orbe)

which from India (or from

the new world)

This phrase is alternative

between India and new world (novo orbe),

and meanwhile is dubitative, because Gottlob thinks that the most important

origin’s land is the India, and the new world is less important. Gottlob,

may be, was aware that the origin of this

bird (what bird?) was from America, but he writes in first place the most

important belief on the origin, the India (where is located Calicut) and he

was not an ornithologist (I think) to have the possibility to discuss the

origin of a bird.

alii ex Numidia primum

venisse volunt

others from Numidia, first

time, affirm that they came

(excuse the bad sequence,

but it’s to give you the possibility to better understand the Latin words)

There we find the big

confusion between Numidia, the land of the Roman’s Guinea fowl, and India.

Never the Numida meleagris became

from India. Thus, India = Abissinia? Abissinia is the central nucleus of

Ethiopia, and in Italy this bird is called Gallina

del Faraone, and the Pharaoh’s kingdom was bordering upon Ethiopia.

horum pulli duorum aut

trium mensium tenerrimi, saporis suavissimi

these fowls, two or three

months aged, are very tender, very taste

This is very important, and

I read it only today. I think that Gottlob is referring to the Guinea fowl,

because never I heard that the turkey is eaten when it’s three months aged;

may be this happened in 1799, but, in Italy, in 1996, absolutely not. Re the

Guinea fowls, I am unaware if they are eaten so young, but I think that it’s

possible also nowadays.

Synthesis: I have

checked rapidly the Gottlob Richter list of birds, and I have not found

neither the turkey nor the Guinea fowl, or, better, these two birds are mixed,

and in the description of the medicamental properties it seems that Gottlob is

referring to the Guinea fowl (2-3 months old). The confusion of Gottlob

Richter is very big and he leaves an open door, i.e. (seu

novo orbe). This door is open on the America, but this possibility is

expressed into parenthesis. This

India is the Abissinia or is Calicut? I think that he was aware that from the

new world was becoming a bird, the turkey, aware because all the scientists

was thinking in this way, but he accepts calecutenses

as alternative name. Do he was aware that the Guinea fowl don’t existed in

India?

We have an Atlantic

mentality, and Nova Scotia is surrounded by the Atlantic, and currently we

think only on trans-atlantic exchanges, and a ship is called Transatlantico

and not Transpacifico!!!. Why

Gottlob had not this mentality? Only once he speaks novo

orbe, and the other mentioned localities are African (Numidia, India =

Abissinia?) or Indian (calecutenses).

May be that, truly, the turkey becomes from Asia.

An ask: do you think that

Richter saw one of these birds during his life? I think not. They are very

different. He was sure only on one thing: the gallos indicos was named also calecutenses.

Obviously, the discussion

is open whether the turkey becomes from America via Columbus or from America

via Asia. Why the adjective Calecutenses? Why Kalakùtas in Lithuanian? Why

Kalkoen in Dutch? Why Turkey in English? (I think that the reference to the

fez is wrong, as I found in a book of Plant’s library, and that Turkey

as Asiatic country it’s true).

Today I was explaining this

problem to a colleague of mine, and rightly he noted that GALLOS INDICOS are

not grouped as Genus gallinaceum, Genus Columbarum, Genus Pavonum. Why?

Because in 1799 there was still a big confusion in this matter.

For example: the Indian

corn, or maize, in Italy we call granoturco.

Please, hear the etymology of granoturco (maize):

prima, grano di Turchia, ma

il nome era già diffuso nel Cinquecento, come nei latini De

Historia Stirpium Commentarii di L.Fuchs (Basilea, 1542) : “E Grecia

autem et Asia in Germania venit, unde Turcicum frumentum appellatum est” (pag

824), o nella traduzione dallo spagnolo all’italiano della Historia naturale e morale delle Indie (Venezia, 1596): “Il Maiz,

che in Castiglia chiamano Formento d’India, et in Italia Formento Turco”

Translation:

before, grain of Turkey,

but the name was already spread in ‘500, as in the Latin De

Historia Stirpium Commentarii of L.Fuchs (Basel, 1542): “From Greece and

Asia came into Germany, whence Turcicum frumentum was called” (pag 824), or

in the translation from Spanish into Italian of the Historia

naturale e morale delle Indie (Venezia, 1596): “The maize, which in

Castillia they call Formento d’India, and in Italy Formento Turco”

Another problem: when began

the extensive cultivation of the American maize in Europe, so extensive to be

cited by Fuchs in 1542? If we feel that Bellon, when speaking on the Coq d’Indie

in 1555, he is referring to an Indian bird (old world, the Asiatic

India), we must agree that Fuchs is referring to a maize becoming from

Asia in his treatise dated 1542.

But, the conclusion

suggested and agreed by Cortelazzo, the author of the Italian Etymological

Dictionary, is that, as says Missaglia (1924), the Italian turco = foreign. Absolutely I don’t agree, and this is not the

moment to discuss why the wood tool to warm the bed during the winter, in

Italy is currently and frequently called prete,

i.e. priest. For me, in the past times the priest was warming the bed and the

wife when her husband was working away, but Cortelazzo has a different point

of view, a much kindly point of view. Supporting my idea there is that in

Cataluña this tool is called monjo,

i.e. monk, monaco in Italian, and

the Italian surnames Monaco, Prete, Vescovo (bishop), Papa, are indicating the

work of the ancestors, and even the paternity. Do you remember the Ius primae noctis? So, the Italian adjective TURCO given to the

GRANO is due to the maize origin from Greece and Asia, as tells Fuchs.

I think that the Germans

are right with their words, which are indefinite about the origin:

welsch = foreign, Italian,

French, but disdainful, as the Italians call Terrone (big earth) an inhabitant of the South, may be because

frequently here you find a dark skin, dark and brown as the earth (not cited

by Cortelazzo, I have thought myself this etymology in this moment)

Welscher Hahn = turkey (or

= Guinea fowl?), as called by Gottlob Richter, i.e. foreign fowl

Welschhuhn, even nowadays

it means turkey, the turkey only

Welschland is the Italy and

even the French Switzerland, i.e. all the countries different from Germany, as

the Romans called Gallus a foreign

people, because gallo and allo

are Indo-Europeans words, meaning foreign (Joze Harrieta, La Lingua Arpitana,

1976). In Greek àllos = different,

another, i.e. alias also used in

English (Corti, 1996!!!).

Welschkorn = maize, and in

this way do we can suppose that the maize becomes from Italy and Switzerland?

Not, it’s foreign!

I have read that the India

had the maize in the 1,000 A.D. (true or not?). Do it’s difficult to think

that the maize arrived in Europe via Turkey?

At this point, don’t

worry, I affirm that genetics they are also linguistic

and history.

If you are interested in the translation of some part of the Richter book, let me know. I will be very happy and I will find the time to do. The use of the Gallos Indicos (turkey - Guinea fowl): they are of easy digestion, they give force, and they are also useful in any age and for the sex (omni aetati et sexui congruens). Not other particular use.

I received the answer from

Netherlands about kalkoen, and I

quote from the letter of Dr Schippers:

5-3-1996 - The name is

mentioned in our Dutch etymoligic dictionary as follows: “The word KALKOEN

exists officially since 1567 in Holland as a degeneration of the word Calcoen,

Kalkoensche henne (Junius, 1567) and Callecoetsche hinne (Plantijn, 1573). The

bird was named after the town of Calcutta, India, in the past known as

Calcoen, Calcoet or in the Indian language: Kolikkodu. Misunderstood was that

the bird came from Middle America, but came for the first time by boat from

Calcutta to Europe.”

My reply to Dr Schippers:

14-3-1996 - I must tell you

that your Dutch etymological dictionary is wrong about Calcutta. I confess

that in a first time I was thinking in the same way about the origin’s city.

I quote from Grolier

Encyclopaedia on CD:

Calcutta was founded by the

British East India Company, which purchased the villages of Sutanati, Kalikata,

and Govindapur in 1698. The name Calcutta is possibly derived from Kalikata,

which was the mythological landing place for the goddess KALI.

My Encyclopaedia De

Agostini, even on CD, reads that Calcutta was founded as farm in 1690 by Job

Charnock, of British East India Company, and in 1696 was built Fort William in

defence of Calcutta. The Treccani Encyclopaedia gives the same date, 1696,

for the foundation of the fort.

The Dutch word kalkoen

exists officially from 1567. Thus, it’s not Calcutta, the city in

Bangladesh, because this city don’t existed in 1567, but Calicut in Kerala

State, founded in the IX century, and Vasco de Gama arrived here in 1498. I

agree with the hypothesis of the arrival of the Turkey in Europe via Asia. My

idea is based only on linguistic data.

From Grolier Encyclopaedia:

The Portuguese navigator

Vasco da Gama led an expedition at the end of the 15th century that opened the

sea route to India by way of the Cape of Good Hope. He was born about 1460 at

Sines, in southwest Portugal, where his father commanded the fortress.

Entering the service of the Portuguese King John II, he helped to seize French

ships in Portuguese ports in 1492. He was a gentleman at court when chosen to

lead the expedition to India.

Many years of Portuguese

exploration down the West African coast had been rewarded when Bartolomeu DIAS

rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488. The Portuguese then planned to send a

fleet to India for spices and to outflank the Muslims in Africa. Vasco da Gama

was placed in command of the expedition and carried letters to the legendary

PRESTER JOHN

[1]

and to the ruler of Calicut, on India's Malabar coast.

Four ships left Lisbon on

July 8, 1497--the São Gabriel, on which da Gama sailed, the São Rafael, the

Berrio, and a storeship. They stopped in the Cape Verde Islands;

from there they did not follow the coast, as earlier expeditions had,

but stood well out to sea. They reached the Cape of Good Hope region on

November 7.

The cape was rounded on

November 22. The expedition stopped on the East African coast, broke up the

storeship, and reached Mozambique on Mar. 2, 1498. There they were assumed to

be Muslims, and the sultan of Mozambique supplied them with pilots, who guided

them on their journey northward. They stopped in Mombasa and Malindi before

sailing to the east. They crossed the Indian Ocean in 23 days, aided by the

Indian pilot Ibn Majid, and reached Calicut on May 20, 1498. The local ruler,

the Zamorin, welcomed the Portuguese, who at first thought that the Indians,

actually Hindus, were Christians.

Unfortunately, the trade

goods and presents provided by the Portuguese king were suitable for Africa,

not India, and the Arabs who dominated trade in the Indian Ocean region viewed

the Portuguese as rivals. As a result, da Gama was unable to conclude a treaty

or commercial agreement in Calicut. After one further stop on the Indian coast,

the Portuguese set out to return with a load of spices. They took three months

to recross the Indian Ocean, however, and so many men died of scurvy that the

São Rafael was burned for lack of a crew.

The expedition made a few stops in East Africa before rounding the Cape

of Good Hope on Mar. 20, 1499. The ships were separated off West Africa in a

storm and reached Portugal at different times. Da Gama stopped in the Azores

and finally reached Lisbon on Sept. 9, 1499.

Da Gama's success led to

the dispatch of another Portuguese fleet, commanded by Pedro Alvares CABRAL.

Some of the men Cabral left in India were massacred, so King Manuel ordered da

Gama to India again. He was given

the title of admiral and left Portugal in February 1502 with 20 ships. The

Portuguese used their naval power on both the East African and Indian sides of

the Indian Ocean to force alliances and establish their supremacy. Da Gama's

mission was a success, and the fleet returned to Lisbon in October 1503.

Da Gama then settled in

Portugal, married, and raised a family. He may have served as an advisor to

the Portuguese crown and was made a count in 1519.

King John III sent him to India in 1524 as viceroy, but he soon became

ill and died in Cochin on Dec. 24, 1524. Vasco da Gama's first voyage to India

linked that area to Portugal and opened the region to sea trade with Europe.

On that foundation the Portuguese soon built a great seaborne commercial

empire, with colonies in India and the Spice Islands.

Goa: Goa is a former

Portuguese colony (1510-1961) located on the western coast of India about 400

km (250 mi) south of Bombay. It was part of the Union Territory of Goa, Daman,

and Diu from 1961 to May 30, 1987, when Goa became the 25th state of India.