Galeotto fu il libro e chi lo scrisse

Galehault has been the book and who wrote it

Dante Alighieri - Hell - V Song - verse 137

Dante finds Paolo and Francesca in the ramparts of the hell

where the lechers are confined, because......one day Paolo and Francesca were reading aside a book dealing with Lancelot of the Lake - one of the Round Table's Knights - as well with his love for king Arthur's wife, Guinevere, with whom Lancelot committed adultery having Galehault as intermediary of their first contact. Several times Paolo and Francesca looked each other, but when they read about the kiss given by Lancelot to Guinevere, then Paolo kissed Francesca and probably both have been killed by Francesca’s husband.

Always of each event is existing the primum movens like for the Universe is existing Who moves the sun and the other stars. The poetry of Dante exceeds the time. If Galehault has been the book of William Plant

, more Galehault has been Fabrizio Focardi

, fellow citizen of Dante, the Runaway Ghibellin: thanks to him a big bagarre broke out.

To each his own. And so the previous inescapable proposition is justified. We will try to clarify the one each other following events. In 1994 springtime I visited Fabrizio living in Florence's outskirts, recompensed by delicious hospitality. I was searching documentation that should help me to clarify some points on chicken's origin. Fabrizio furnished me with the essential information and showed meThe Origin Evolution Distribution of the Domestic Fowl (1986) of the Australian William Plant and gave me the address of Veronica Mayhew

, world’s expert in birds’ books, old and new, who has her stronghold in London’s neighbourhoods.

I wrote to Veronica and she sent me the first of a series of books, so much that at a certain point she wonders whether I'm writing one or two books on chicken's genetics. Sarcastic, isn’t it? In the first pages of Plant’s book I stumble across a Latin's error: when the Author is dealing with the classification of the domestic chickens in at least 3 evolutionary lineages (Bankivoids, Malays and Asiatics), he is adopting a linneoid terminology, i.e. Gallus pluma crusis. I think that it's a typographical error since the genitive of the Latin word crus, leg, does cruris. In a following page the mistake is repeated. I take note and in a gulp I read a harvest of historical and archaeological data which must have cost very heavy work as in fact it has been.

I don’t like to speak on typographical errors, because the extreme pedantry could be offensive, but for love of the science it’s incorrect to be silent. Whereas Plant is stating to be glad of possible suggestions, in July I resolve to write to him and with my elementary English I drop an explanatory line.

The Plant's answer is immediate, he is happy of the correction, and, like often it happens, it's an error passing on from a book to another, from a book from which he acquired the terminology.

Summing up: the correspondence with Plant becomes frequent, burdened with difficult questions which Bill sometimes is not able to answer to: in this case he sends me lots of photocopies. I start to be fond of this man, my letters become more and more long and my English less and less distasteful.

One day Bill sends me an issue of Australasian Poultry, priceless magazine published in Werribee, in the Australian state of Victoria (its capital is Melbourne). The issue of February-March 1995 contains an article signed Robert Johnstone and titled Pekin Bantams and Short Wave Radio, dealing with the hobby of amateur radio that Bill is cultivating since 1939

, by which he communicates throughout the world often making up for the serious visual problems because of two cornea's transplants. The radio also allowed him to exchange information on chickens and then to correspond with scientists and breeders, mostly from the Japanese area.

In March 1995 I find myself with still all vacation of the past year and I feel that it could be used in doing a short visit to Australia. At his home Bill might guard a cultural patrimony, and so, thirsty of news to give a final touch to the heavy, pedantic and arabesque treatise on fowl’s genetics not yet given birth to, I write to Bill in asking whether I can visit him. The answer is positive. Maurizio Tona, our Federal Breeders’ President, aware of my plans, arranges a silver medal for Bill with the symbol of the Federation as well the praises for his daily scientific search engraved on it that represents a University's benchmark even internationally known, what am I telling, intercontinentally known.

May 8th I put my foots on Australian ground after a trip for only no smokers which the misfortune reserved me. From London to Sydney the flight's hours amount to 21 (11 for London-Bangkok and 10 for the final leap to Sydney), with a break of half an hour in the Thai's capital, exploited for at least 3 cigarettes. Out from the Sydney’s airport

-

, at the first lights of the dawn, finally I taste a cigarette in company of a native lady, she also dissenting on this prohibitionism of purely Australian taste, since the English one is much more as roses' water, although the idea of this smoke free flight is an offspring of the English British Airways.

For a moment the cigarette makes me forgetting the parmigiano cheese seized by customs because of fear of bacterial importation in a land which already has had and still is having its ecological troubles due to the rabbit's introduction. It's quite useless my affirmation that it's an at least 5 years matured cheese and that the bacterial flora is selected and perfumed like a bud of roses. After the short discussion made painful by my hesitant English, my invitation to the police officer is of to don't destroy that good of God, but to let it dissolve in mouth, as gem of a cheese's stock that would have stood up to the work of the best ice’s masters. The answer had been peremptory: it'll be destroyed. Don't be surprised at that. Bill showed me a newspaper's clipping telling about the trial and the fine (90 million of liras) of an Australian gentleman who tried to introduce eggs furtively without the due quarantine.

Only a few time after my return to Italy I could have interpreted a gesture that seemed to me a sign of courtesy: nearly twenty minutes before the landing in Sydney, a steward is going across the seats' rows in brandishing a spray tank which spreads a pleasantly perfumed cloud. I thought: look at, they are perfuming the air also!. On the contrary not, it was the disinfection, a disinfection that, in time, turned itself into a ritual deprived of any hygienic value.

I swear that in Australia you can live at easy, in the Post Office you can find any sort of container for any deviltry you want to mail, the trains travel on time

, if you book a train trip the cars will stop level with the painted letters on the platform which is levelled to the floor of the wagon and corresponding to the assigned coach, when leaving a station you find a poster announcing in advance the next station, the crowds in front of the airport's Sesamo are quite useless in as two colour videos are giving the images of the two corridors crossed by coming passengers, so you are not forced to wave your arms to be located by relatives and friends.

But there exists some rake-off unaccepted by us, who are Mediterraneans. You have to travel by bicycle with helmet (like in Finland), you cannot smoke neither in airport neither in train because reserved areas don't exist nevertheless almost all people are smoking. On the half-minute stop in a little railway station it's a crowd of people toward the wagon's exit to do a drag on a cigarette in keeping the head out of the door. And the cigarette is not recovered for the next stop like we would do in Italy, extinguishing it on the shoe's sole: they simply throw it away. You must know that, if the gasoline costs 700 liras a litre, the average cost of 25 cigarettes is 7,000 liras [in Italy: 1 gasoline litre = 1,500 liras - 25 cigarettes 3,600 liras on average]. I do think that the prohibitionism has its being reason in the greater government’s incomes ensured by the cigarettes’ iper-waste becoming from two smoke's gulps done greedily and helter-skelter.

Taking the Plant’s instructions in my pocket, I catch a taxi for Sydney's central station

-

-

-

where I book a train up to Maitland, 16,000 inhabitants, around 200 km northwards the capital. Two hours of trip cheered by an infinity of eucalyptuses, lagoons, ranges like our Appennines, grassy spaces of an English green used for golf. The train is on time and at 13:30 o'clock William John Plant, 74 well borne years, and his son David, they are waiting for me at the station

-

. At first sight I read the cordiality in their gestures and in the look. They take me to the Caledonian Hotel

, a stonesthrow from the railway station, and then we reach the Bill's house, in wood, plunged in the green, in the western outskirts of the town.

Here I will spend hours and hours in catching documentation, often photocopying, sometimes directly translating the more meaningful passages of problems from time suspended which finally find an answer. Pick up and pick up, after a month I'm forced to bequeath to Bill a tracksuit because my suitcase is bursting and my hand luggage, that I throw with indifference - and with a Maciste’s air - in front of the eyes of the airport check-in employee, only looking at it it’s telling as much it’s heavy: 20 kgs. I sketched an excuse to get mercy: "That's because of the science!" They asked whether I was a scientist, I answered half yes and half not, but truly the flight was full loaded and so gladly I paid the excess: if I had acquired what I was jealously carrying to Italy, the price would have been at least ten times so much.

In Bill's company the day was running peacefully, often I was breaking off my searches and we were exchanging our points of view on chicken's genetics, not only, but on the life, sometimes bitter, sometimes cheered by friendship like that was strengthening within us. At midday a small snack, maybe two salty peanuts along with a beer; for dinner I exhibited myself in risotti which ever have been my forte.

Saffron and mushrooms had the approval of the customs, and then Bill couldn't stop himself from communicating via ether

to the friends who cast anchor offshore of New Caledonia: "Today very tasteful Italian food, Risotto milanesa." And I, suddenly, in background: "...alla milanese...", and I heartly laughed up one's sleeve. Also Bob, the old big dog

, didn't disdain my kitchen, licking its moustaches by now hoary when he could attack a risotto with asparagus, or with four cheeses, or alla milanese, or seasoned with garlic-oil-capsicum.

Friday is the day on which Bill, he also handicapped because of his eyes but less than others are, he devotes himself to the meeting of all that people who have had various health problems. A bus of Maitland's Community goes round the town, a trip on a vast territory, not studded by buildings but by cottages of one floor at maximum

-

-

-

. I took part to three meetings and I could tell that never I felt myself from abroad. I fraternised immediately and I tried to cheer somehow those few hours I was spending with people that, beyond to own beloveds, they have also lost the well-being.

Few days after my arrival I visited the Newcastle's hospital, nearly 30 km from Maitland. Newcastle

-

-

is a harbour on the Pacific mainly used for the coal which is plentifully quarried in Hunter Valley where Maitland is laying. Never I saw trains so long and so overloaded by the precious material. So long like in the movie pictures!

The Newcastle’s Hospital is a wonderful work of modern architecture, functional, ample, pleasant

-

-

, plunged into the eucalyptuses, in the surroundings of the city and where a very wide park is stretching: here, without hardships, I admired the ancient inhabitants of this Southern land: kangaroos

-

, koalas

, emus, swarms of yellow crested cockatoos

, ducks, native hens

-

; no pelicans and black swans

, which at the contrary in wildness dot the marshes that often frame the railway. What a capital in black swans! I told to Bill, acquainting him with the cost in Italy of a couple of these birds. In the Bill's garden I saw a rabbit and suddenly informed him, thinking that it was escaped from its pen. No, Bill told, it’s only a rabbit which didn't fall into the trap. A year the cat of my sister Joyce lost hind limbs. We have still plenty of them around.

Every day I was acquiring new experiences and material, each day a small or a big progress. Each night about 10 o’clock, when in front of 54 of Bonar Street

I was awaiting for a taxi to get the hotel, Bill was asking "Some progress today?", and I did reply yes. It was the truth, like were true the Bill's dedication and the care in order that each day would not to be empty and useless. They havn't been empty days, I swear, repaid over all by a friendship it's difficult to run into. Bill inspires confidence and devotion, more and more difficult good to retrieve.

Halfway of my stay in Maitland we go to Taree, 200 km northwards. The train winds slowly on the rails that skirt rocky hillocks used as grazing

. Bill states that there exist cultivated soils in New South Wales, but I don't agree, because never he saw to what kind of chessboard has been transformed our Padana Lowland. They are pastures for cattle and sheep, which represent a big slice of the rural activity

. Taree is a little town, 20,000 inhabitants roughly, with a beautiful commercial centre, the Mall, wide streets like in all recently founded cities, recently in comparison with our ones which often are bosting at least of a Roman founder. Here everything began 200 years ago, and they made great strides thanks to the people's mixture. In Sydney is printed a daily newspaper even in Greek.

Frank Fogarty is awaiting for us in the station, he also widower like me and Bill, without an arm

, Irish stemmed, a daughter nun, another one in England working with very good results in computer science, two sons. Frank is a man of few words but with a big heart like so. His house is ours. Man of big talent, stubborn like an Irishman, he put on in his own mind to transfer the barred of the Plymouth Rock, the par excellence barred, the most beautiful in absolute, to transfer it into the Pekin

-

, like here righthly they call the dwarf Cochin.

He turned out well: he took dwarf Plymouth Rock, mated it with the Pekin and recovered all latter's characters. His Pekin is barred, our one is only cuckoo. His selection has been iron, so iron that one day, coming back from a stroll to the pens, I tell to Frank that I saw there a dead Pekin hen.

He does reply me that she wasn't beautiful and that he stretched her neck (I was imagining him in stretching her neck with only an arm!) and that he forgot to take away. I blush with shame, because my selector's ability is null and void, I feel myself an unworthy ANSAV member (our Italian Breeders' Federation).

Frank also is worrying about my manias. He accompanies me to a bookshop, a step that cannot be missed out when I reach a new town, he accompanies me to a photographic hunting but I'm able to scrape together only few egrets - which crowd in keeping the cattle company to ensure their parasites - and some more sample of straw-necked ibis

. But the photographic hunting is too much scanty and then Frank sails for a farm, where turkeys are raised. I wonder that in Italy I have seen plenty of turkeys, but I'll go to see the Australian ones too! Turkeys aren't any more and so he shows me only the pen where they mate and we go back to home.

In the late afternoon we get out of Taree for about ten kms reaching a relic of pluvial forest

, where hundreds year old banyans do lord it, the Ficus benghalensis

, with a huge foliage having a circumference sometimes of 500 meters, adorned like Christmas trees by restless clusters of fruit bats

-

waiting for the dusk to feed on fruits and nectar. This tree is so huge that they say that Alexander the Great recovered under its foliage 7,000 men during his expedition to India.

Finally it turns clear why Frank wants to show me the turkey. It's the brush turkey, so-called because it resembles a turkey - but it isn't - and because it piles up enormous lot of leaves and rubble to build a nest. The Australian brush turkey is the common name of Alectura lathami

(alectura means tail of rooster), galliform megapode spread along the eastern Australian coastal belt. The eggs are laid the point downwards, the male looks after the rubble airing adjustement in order to slacken or poke the fermentative processes which supply the required warmth to their disclosure. A big natural incubator from which the chicks come out quite self-sufficient and never will know the mother, running freely through the forest.

The photocopies of the correspondence Bill is doing since 25 years with scientists and breeders through the world form part of 20 kgs baggage's excess. As soon as I began to look through the Bill's files I realised how much these letters were priceless: genetic, archaeological and evolutionistic problems are handled in plain epistolary style, not in the irritating academic lilt. I propose to Bill to do a book of them, he hesitates, then agrees, and at present it's in processing: I'm preparing the master copies. Then, the friend Tony Mills, armed with an ultramodern photocopier, will see to multiply the master copies when corrected in Italy by the undersigned and by Bill, because next spring I will have the honour of his visit during two months.

Tony lives in open country, 5 km from the centre, 10 meters from the railway to Taree. He breeds chickens it's wortwhile to see. He is the President of the Pekin Club of the NSW and Bill is its Assistant Secretary, while David Plant is Secretary; they assembled a unique work: the Australian Pekin's standard, result of years and years of searches and correspondence with the late Frank Gary (USA - American Bantam Association), a book that should not be missing in our library, nevertheless it's in English.

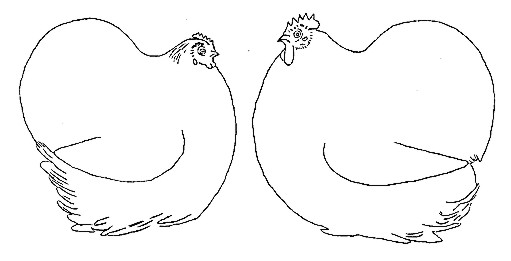

The Pekin

according with the standard of the homonymous club

of New South Wales

This ideal has been attained by guidance of Bill PlantHow this book is born? In 1982 William Plant published a volume containing general information on Pekin's history and breeding, entitled Pekin Bantam in Australia. In the same period, within the Pekin Club of the NSW, it became more and more pressing the request of a formulation of the Australian Pekin colours' standard, because quite a lot of Breeders during the poultry shows each time exhibited new varieties. Meanwhile the Club was picking up information as much as possible about this race, and thus the standard decreed 18 colour's varieties, the type was reviewed making it more easily understandable through plenty of articles regularly appeared in quarterly Club's Newsletter. The authors' dedication was not in providing photographic images, but on the contrary in giving sketches in order the ideal type to be reached. All these things along with the elements on raising and selecting have been assembled in adding basic genetics' information to address the breeder in getting the different colours by the due crossings.

The co-editors picked up all the information patiently scraped together during 12 years, allowing the Pekin's fanciers to have available a complete and exhaustive work from every point of view in which to find an answer for any query. The history of the Club - founded in 1955 - was also restored. Tony Mills and David Plant worked on the section regarding the Standard with David's co-ordination, Chris Hardman put the manuscripts into the computer allowing the publication of the work that came to light in July 1993, spread throughout Australia, New Zealand, Great Britain, Germany, USA, Italy, Ukraine and France.

Indisputably Tony's breeding offers the opportunity to judge the selecting abilities of the Australian friends: giant

-

and dwarf

Ancona carrying very few white even in old birds, dwarf light Wyandotte

, giant and dwarf

Chinese Langshan black, blue and white (rare), obviously Pekin in nearly all colours, exceptional the white.

In spite of the almost grotesque hygienic precautions on the aircraft, the germs are omnipresent. Strolling between Tony's cages and fences I stumble upon a mottled Pekin cock with a good sinusitis. I ask from Tony whether he is treating the illness: "Yes, by antibiotics." I suggest him to operate the fowl being the sinusitis at a such point that the medication can only to stop the infection's spreading to the surrounding tissues and not to work out the sinusitis. I ask from Tony whether sometimes he has done a such operation. Almost startled: "No!" We prepare a surgical table using the patio of the house being of a suitable height, as sheet a newspaper, as teasel a paper handkerchief, as scalpel half shave's blade, to clean up a crochet. A cut like a Master, a swift cleaning of the pus, and the rooster breathes a sigh of relief, obviously not through the nose yet.

The stench of the abundant and evil-smelling pus will persist in my nose, as usual, the whole day. It was the last day of my stay in Maitland and as I couldn't have news the following day, I wrote to Tony to know about the cockerel. All right and it recovered.

At 8 o'clock of the morning of Saturday 3 June 1995, Bill and David help me to load up my luggage on the train. Obviously tears are restrained, we are men after all! But we will meet again, I tell me, we somehow will meet again.

Bill accepted my invitation

and he will attend as observer the Entente Européenne in Bergamo in 1996.Valenza, December 8th 1995

Translation reviewed by Stefania Fersini - Pavia