Lessico

Antologia Palatina

Raccolta di 3700 epigrammi greci, composti dall'età classica all'età bizantina, cosiddetta per essere stata scoperta, nel 1607, in un codice della biblioteca dell'elettore palatino di Heidelberg (codice gr. 23), dall'umanista francese Claudio Salmasio (Claude de Saumaise, Semur-en-Auxois 1588 - Spa 1653).

Deriva

in gran parte dall'Antologia di Costantino Cefala, un erudito della

prima metà del sec. X al servizio dell'imperatore di Costantinopoli

Costantino VII Porfirogenito![]() (905-959). Cefala riunì 3 raccolte precedenti: la Corona, la prima

antologia di epigrammi, pubblicata da Meleagro di Gadara (sec. II-I

aC), contenente carmi attribuiti a una cinquantina di poeti, da Archiloco a

Meleagro stesso; la Corona (ca. 40 dC) di Filippo di Tessalonica,

contenente poeti da Meleagro a Filippo di Tessalonica stesso; e il Ciclo

(ca. 560) di Agazia di Mirina. Vi aggiunse estratti delle opere di altri poeti

e distribuì tutta la materia in 15 libri, secondo l'argomento: cristianesimo,

iscrizioni, poesie d'amore, morali, conviviali; epitaffi, indovinelli e

bizzarrie, ecc.

(905-959). Cefala riunì 3 raccolte precedenti: la Corona, la prima

antologia di epigrammi, pubblicata da Meleagro di Gadara (sec. II-I

aC), contenente carmi attribuiti a una cinquantina di poeti, da Archiloco a

Meleagro stesso; la Corona (ca. 40 dC) di Filippo di Tessalonica,

contenente poeti da Meleagro a Filippo di Tessalonica stesso; e il Ciclo

(ca. 560) di Agazia di Mirina. Vi aggiunse estratti delle opere di altri poeti

e distribuì tutta la materia in 15 libri, secondo l'argomento: cristianesimo,

iscrizioni, poesie d'amore, morali, conviviali; epitaffi, indovinelli e

bizzarrie, ecc.

L'antologia in nostro possesso è una versione (accresciuta e rivista in epoca di poco più tarda) di quella di Cefala. Assai belli sono i circa 300 epigrammi amorosi del libro V, specie quelli di Callimaco, Asclepiade, Meleagro e Paolo Silenziario.

Antologia Planudea

Raccolta di epigrammi greci compilata a Costantinopoli dal monaco bizantino Massimo Planude (Nicomedia ca. 1260 - Costantinopoli 1310). Egli utilizzò una raccolta assai simile a quella di Costantino Cefala (v. Antologia palatina), variando l'ordine dei componimenti, eliminando quelli sconvenienti e introducendone ca. 400 nuovi, per lo più descrizioni di opere d'arte, che ricavò dal testo di Theodoros Xanthopulos. L'Antologia giunse in Europa attraverso il cardinale Bessarione (m. 1472), che legò i suoi libri alla Biblioteca Marciana di Venezia (dove è conservato il codice gr. 481). Pubblicata da Giano Lascaris a Firenze nel 1494, l'Antologia fu l'unica conosciuta fino alla scoperta della Palatina. In appendice a quest'ultima sono di solito pubblicati gli epigrammi propri della sola Planudea.

Antologia Palatina

L'Antologia Palatina è una raccolta di epigrammi greci compilata tra la fine del IX e l'inizio del X secolo dC. da uno studioso bizantino, tale Costantino Cefala. Essa consta di circa 3700 epigrammi, suddivisi in 15 libri. Tale opera venne rinvenuta dall'umanista Claude Saumaise nel 1607 presso la Biblioteca di Heidelberg (detta Palatina, da cui il nome di Antologia Palatina). Oggi la maggior parte del testo si trova in Germania, mentre la rimanente è collocata presso la Biblioteca Nazionale di Parigi.

L'Antologia

Palatina è costituita dai componimenti di svariati scrittori, sia cristiani

che pagani. Questi ultimi sono comunque maggioritari e prevale tra essi il

poeta Meleagro di Gadara del quale è riportata una sua raccolta di epigrammi,

la Corona (nella quale sono inseriti anche testi di Alceo![]() e Anacreonte); compaiono anche poesie di Callimaco, Leonida di Taranto,

Simonide e un unico epigramma di Apollonio Rodio. Tra i cristiani spicca

Gregorio Nazianzeno, i cui componimenti occupano l'intero libro VIII. Vi sono

inoltre vari poeti anonimi e appartenenti al periodo della lirica arcaica.

e Anacreonte); compaiono anche poesie di Callimaco, Leonida di Taranto,

Simonide e un unico epigramma di Apollonio Rodio. Tra i cristiani spicca

Gregorio Nazianzeno, i cui componimenti occupano l'intero libro VIII. Vi sono

inoltre vari poeti anonimi e appartenenti al periodo della lirica arcaica.

I

contenuti dell'Antologia sono di grande varietà, come del resto già buona

parte delle raccolte di epigrammi antichi (si pensi a quella di Marziale![]() o di Catullo), e spaziano dagli argomenti amorosi a quelli descrittivi, dai

lamenti funebri ad argomenti burleschi o d'intrattenimento.

o di Catullo), e spaziano dagli argomenti amorosi a quelli descrittivi, dai

lamenti funebri ad argomenti burleschi o d'intrattenimento.

I 15 libri sono divisi per argomento, tranne il tredicesimo e il quindicesimo che affrontano le tematiche più varie. Nello specifico, i libri V e XII sono dedicati ad argomenti erotici (il dodicesimo affronta il topos classico della pederastia), mentre nel libro VII troviamo epigrammi funebri; i libri I e VIII trattano argomenti cristiani, il decimo contiene sentenze moraleggianti e il quattordicesimo espone vari indovinelli, quesiti logici, nonché enigmi e oracoli. Infine, i libri II, III e IX sono di tipo descrittivo.

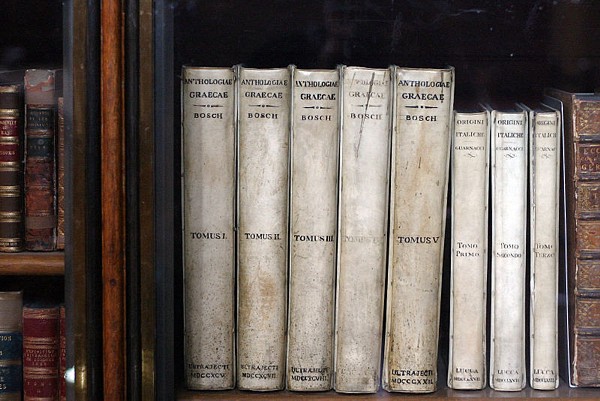

The van Bosch and van Lennep version of The Greek Anthology (in five vols., begun by Bosch in 1795, finished and published by Lennep in 1822). Photographed at The British Museum, London. Contains the metrical Latin version of Grotius's Planudean (Planudes) version of the Anthology. Heavily illustrated. It also reprints the very error-prone Greek text of the Wechelian edition (1600) of the Anthology, which is itself simply a reprint of the 1566 Planudean edition by Henricus Stephanus.

The Greek Anthology (also called Anthologia Graeca or, sometimes, the Palatine Anthology) is a collection of poems, mostly epigrams, that span the classical and Byzantine periods of Greek literature.

While papyri containing fragments of collections of poetry have been found in Egypt, the earliest known anthology in Greek was compiled by Meleager of Gadara, under the title Anthologia, or "Garland." It contained poems by the compiler himself and forty-six other poets, including Archilochus, Alcaeus, Anacreon, and Simonides. In his preface to his collection, Meleager describes his arrangement of poems as if it were a head-band or garland of flowers woven together in a tour de force that made the word "Anthology" a synonym for a collection of literary works for future generations.

Meleager's Anthology was popular enough that it attracted later additions. Prefaces to the editions of Philippus of Thessalonica and Agathias were preserved in the Greek Anthology to attest to their additions of later poems. The definitive edition was made by Constantine Cephalas in the tenth century AD, who added a number of other collections: homoerotic verse collected by Straton of Sardis in the second century AD; a collection of Christian epigrams found in churches; a collection of satirical and convivial epigrams collected by Diogenianus; Christodorus' description of statues in the Byzantine gymnasium of Zeuxippos; and a collection of inscriptions from a temple in Cyzicus.

The scholar Maximus Planudes also made an edition of the Greek Anthology, which while adding some poems, primarily deleting or bowdlerizing many of the poems he felt were impure. His anthology was the only one known to Western Europe (his autograph copy, dated 1301 survives; the first edition based on his collection was printed in 1494) until 1606 when Claudius Salmasius found in the library at Heidelberg a fuller collection based on Cephalas. The copy made by Salmasius was not, however, published until 1776, when Richard François Philippe Brunck included it in his Analecta. The first critical edition was that of F. Jacobs (13 vols. 1794-1803; revised 1813-17).

Since its transmission to the rest of Europe, the Greek Anthology has left a deep impression on its readers. In a 1971 article on Robin Skelton's translation of a selection of poems from the Anthology, a reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement wrote, "The time of life does not exist when it is impossible to discover in it a masterly poem one had never seen before." Its influence can be seen on writers as diverse as Propertius, Ezra Pound and Edgar Lee Masters. Since full and uncensored English translations became available at the end of the 20th century, its influence has widened still further.

Literary history

The art of occasional poetry had been cultivated in Greece from an early period -- less, however, as the vehicle of personal feeling than as the recognized commemoration of remarkable individuals or events, on sepulchral monuments and votive offerings: Such compositions were termed epigrams, i.e. inscriptions. The modern use of the word is a departure from the original sense, which simply indicated that the composition was intended to be engraved or inscribed.

Such a composition must necessarily be brief, and the restraints attendant upon its publication concurred with the simplicity of Greek taste in prescribing conciseness of expression, pregnancy of meaning, purity of diction and singleness of thought, as the indispensable conditions of excellence in the epigrammatic style. The term was soon extended to any piece by which these conditions were fulfilled.

The transition from the monumental to the purely literary character of the epigram was favoured by the exhaustion of more lofty forms of poetry, the general increase, from the general diffusion of culture, of accomplished writers and tasteful readers, but, above all, by the changed political circumstances of the times, which induced many who would otherwise have engaged in public affairs to addict themselves to literary pursuits. These causes came into full operation during the Alexandrian era, in which we find every description of epigrammatic composition perfectly developed.

About 60 BC, the sophist and poet, Meleager of Gadara, undertook to combine the choicest effusions of his predecessors into a single body of fugitive poetry. Collections of monumental inscriptions, or of poems on particular subjects, had previously been formed by Polemon Periegetes and others; but Meleager first gave the principle a comprehensive application.

His selection, compiled from forty-six of his predecessors, and including numerous contributions of his own, was entitled The Garland (Stefanos), and in an introductory poem each poet is compared to some flower, fancifully deemed appropriate to his genius. The arrangement of his collection was alphabetical, according to the initial letter of each epigram.

In the age of the emperor Tiberius (or Trajan, according to others) the work of Meleager was continued by another epigrammatist, Philippus of Thessalonica, who first employed the term anthology. His collection, which included the compositions of thirteen writers subsequent to Meleager, was also arranged alphabetically, and contained an introductory poem. It was of inferior quality to Meleager's.

Somewhat later, under Hadrian, another supplement was formed by the sophist Diogenianus of Heracleia (2nd century A.D.), and Straton of Sardis compiled his elegant but tainted Musa Puerilis from his productions and those of earlier writers.

No further collection from various sources is recorded until the time of Justinian, when epigrammatic writing, especially of an amatory character, experienced a great revival at the hands of Agathias of Myrina, the historian, Paulus Silentiarius, and their circle. Their ingenious but mannered productions were collected by Agathias into a new anthology, entitled The Circle; it was the first to be divided into books, and arranged with reference to the subjects of the pieces.

These and other collections made during the Middle Ages are now lost. The partial incorporation of them into a single body, classified according to the contents in 15 books, was the work of a certain Constantinus Cephalas, whose name alone is preserved in the single MS. of his compilation extant, but who probably lived during the temporary revival of letters under Constantine Porphyrogenitus, at the beginning of the 10th century.

He appears to have merely made excerpts from the existing anthologies, with the addition of selections from Lucillius, Palladas, and other epigrammatists, whose compositions had been published separately. His arrangement, to which we shall have to recur, is founded on a principle of classification, and nearly corresponds to that adopted by Agathias. His principle of selection is unknown; it is only certain that while he omitted much that he should have retained, he has preserved much that would otherwise have perished.

The extent of our obligations may be ascertained by a comparison between his anthology and that of the next editor, the monk Maximus Planudes (AD 1320), who has not merely grievously mutilated the anthology of Cephalas by omissions, but has disfigured it by interpolating verses of his own. We are, however, indebted to him for the preservation of the epigrams on works of art, which seem to have been accidentally omitted from our only transcript of Cephalas.

The Planudean (in seven books) was the only recension of the anthology known at the revival of classical literature, and was first published at Florence, by Janus Lascaris, in 1494. It long continued to be the only accessible collection, for although the Palatine MS., the sole extant copy of the anthology of Cephalas, was discovered in the Palatine library at Heidelberg, and copied by Saumaise (Salmasius) in 1606, it was not published until 1776, when it was included in Brunck's Analecta Veterum Poetarum Graecorum.

The MS. itself had frequently changed its quarters. In 1623, having been taken in the sack of Heidelberg in the Thirty Years' War, it was sent with the rest of the Palatine Library to Rome as a present from Maximilian I of Bavaria to Pope Gregory XV, who had it divided into two parts, the first of which was by far the larger; thence it was taken to Paris in 1797. In 1816 it went back to Heidelberg, but in an incomplete state, the second part remaining at Paris. It is now represented at Heidelberg by a photographic facsimile.

Brunck's edition was superseded by the standard one of Friedrich Jacobs (1794-1814, 13 vols.), the text of which was reprinted in a more convenient form in 1813-1817, and occupies three pocket volumes in the Tauchnitz series of the classics.

The best edition for general purposes is perhaps that of Dubner in Didot's Bibliotheca (1864-1872), which contains the Palatine Anthology, the epigrams of the Planudean Anthology not comprised in the former, an appendix of pieces derived from other sources, copious notes selected from all quarters, a literal Latin prose translation by Jean François Boissonade, Bothe, and Lapaume and the metrical Latin versions of Hugo Grotius. A third volume, edited by E. Cougny, was published in 1890. The best edition of the Planudean Anthology is the splendid one by van Bosch and van Lennep (1795-1822). There is also a complete edition of the text by Stadtmuller in the Teubner series.

Arrangement

The Palatine MS., the archetype of the present text, was transcribed by different persons at different times, and the actual arrangement of the collection does not correspond with that signalized in the index. It is as follows: Book 1. Christian epigrams; 2. Christodorus's description of certain statues; 3. Inscriptions in the temple at Cyzicus; 4. The prefaces of Meleager, Philippus, and Agathias to their respective collections; 5. Amatory epigrams; 6. Votive inscriptions; 7. Epitaphs; 8. The epigrams of Gregory of Nazianzus; 9. Rhetorical and illustrative epigrams; 10. Ethical pieces; 11. Humorous and convivial; 12. Strata's Musa Puerilis; 13. Metrical curiosities; 14. Puzzles, enigmas, oracles; 15. Miscellanies. The epigrams on works of art, as already stated, are missing from the Codex Palatinus, and must be sought in an appendix of epigrams only occurring in the Planudean Anthology. The epigrams hitherto recovered from ancient monuments and similar sources form appendices in the second and third volumes of Dübner's edition.

Style and value

One of the principal claims of the Anthology to attention is derived from its continuity, its existence as a living and growing body of poetry throughout all the vicissitudes of Greek civilization. More ambitious descriptions of composition speedily ran their course, and having attained their complete development became extinct or at best lingered only in feeble or conventional imitations. The humbler strains of the epigrammatic muse, on the other hand, remained ever fresh and animated, ever in intimate union with the spirit of the generation that gave them birth. To peruse the entire collection, accordingly, is as it were to assist at the disinterment of an ancient city, where generation has succeeded generation on the same site, and each stratum of soil enshrines the vestiges of a distinct epoch, but where all epochs, nevertheless, combine to constitute an organic whole, and the transition from one to the other is hardly perceptible. Four stages may be indicated:

The Hellenic proper, of which Simonides of Ceos (c. 556-469 BC), the author of most of the sepulchral inscriptions on those who fell in the Persian wars, is the characteristic representative. This is characterized by a simple dignity of phrase, which to a modern taste almost verges upon baldness, by a crystalline transparency of diction, and by an absolute fidelity to the original conception of the epigram. Nearly all the pieces of this era are actual bona fide inscriptions or addresses to real personages, whether living or deceased; narratives, literary exercises, and sports of fancy are exceedingly rare.

The epigram received a great development in its second or Alexandrian era, when its range was so extended as to include anecdote, satire, and amorous longing; when epitaphs and votive inscriptions were composed on imaginary persons and things, and men of taste successfully attempted the same subjects in mutual emulation, or sat down to compose verses as displays of their ingenuity. The result was a great gain in richness of style and general interest, counterbalanced by a falling off in purity of diction and sincerity of treatment. The modification -- a perfectly legitimate one, the resources of the old style being exhausted -- had its real source in the transformation of political life, but may be said to commence with and to find its best representative in the playful and elegant Leonidas of Tarentum, a contemporary of Pyrrhus, and to close with Antipater of Sidon, about 140 BC (or later). It should be noticed, however, that Callimachus, one of the most distinguished of the Alexandrian poets, affects the sternest simplicity in his epigrams, and copies the austerity of Simonides with as much success as an imitator can expect.

By a slight additional modification in the same direction, the Alexandrian passes into what, for the sake of preserving the parallelism with eras of Greek prose literature, we may call the Roman style, although the peculiarities of its principal representative are decidedly Oriental. Meleager of Gadara was a Syrian; his taste was less severe, and his temperament more fervent than those of his Greek predecessors; his pieces are usually erotic, and their glowing imagery sometimes reminds us of the Song of Solomon. The luxuriance of his fancy occasionally betrays him into far-fetched conceits, and the lavishness of his epithets is only redeemed by their exquisite felicity. Yet his effusions are manifestly the offspring of genuine feeling, and his epitaph on himself indicates a great advance on the exclusiveness of antique Greek patriotism, and is perhaps the first clear enunciation of the spirit of universal humanity characteristic of the later Stoic philosophy. His gaiety and licentiousness are imitated and exaggerated by his somewhat later contemporary, the Epicurean Philodemus, perhaps the liveliest of all the epigrammatists; his fancy reappears with diminished brilliancy in Philodemus's contemporary, Zonas, in Crinagoras, who wrote under Augustus, and in Marcus Argentarius, of uncertain date; his peculiar gorgeousness of colouring remains entirely his own. At a later period of the empire another genre, hitherto comparatively in abeyance, was developed, the satirical. Lucillius, who flourished under Nero, and Lucian, more renowned in other fields of literature, display a remarkable talent for shrewd, caustic epigram, frequently embodying moral reflexions of great cogency, often lashing vice and folly with signal effect, but not seldom indulging in mere trivialities, or deformed by scoffs at personal blemishes. This style of composition is not properly Greek, but Roman; it answers to the modern definition of epigram, and has hence attained a celebrity in excess of its deserts. It is remarkable, however, as an almost solitary example of direct Latin influence on Greek literature. The same style obtains with Palladas, an Alexandrian grammarian of the 4th century, the last of the strictly classical epigrammatists, and the first to be guilty of downright bad taste. His better pieces, however, are characterized by an austere ethical impressiveness, and his literary position is very interesting as that of an indignant but despairing opponent of Christianity.

The fourth or Byzantine style of epigrammatic composition was cultivated by the beaux-esprits of the court of Justinian. To a great extent this is merely imitative, but the circumstances of the period operated so as to produce a species of originality. The peculiarly ornate and recherché diction of Agathias and his compeers is not a merit in itself, but, applied for the first time, it has the effect of revivifying an old form, and many of their new locutions are actual enrichments of the language. The writers, moreover, were men of genuine poetical feeling, ingenious in invention, and capable of expressing emotion with energy and liveliness; the colouring of their pieces is sometimes highly dramatic.

It would be hard to exaggerate the substantial value of the Anthology, whether as a storehouse of facts bearing on antique manners, customs and ideas, or as one among the influences which have contributed to mould the literature of the modern world. The multitudinous votive inscriptions, serious and sportive, connote the phases of Greek religious sentiment, from pious awe to irreverent familiarity and sarcastic scepticism; the moral tone of the nation at various periods is mirrored with corresponding fidelity; the sepulchral inscriptions admit us into the inmost sanctuary of family affection, and reveal a depth and tenderness of feeling beyond the province of the historian to depict, which we should not have surmised even from the dramatists; the general tendency of the collection is to display antiquity on its most human side, and to mitigate those contrasts with the modern world which more ambitious modes of composition force into relief. The constant reference to the details of private life renders the Anthology an inexhaustible treasury for the student of archaeology; art, industry and costume receive their fullest illustration from its pages. Its influence on European literatures will be appreciated in proportion to the inquirer's knowledge of each. The further his researches extend, the greater will be his astonishment at the extent to which the Anthology has been laid under contribution for thoughts which have become household words in all cultivated languages, and at the beneficial effect of the imitation of its brevity, simplicity, and absolute verbal accuracy upon the undisciplined luxuriance of modern genius.

Translations, imitations, &c.

The best versions of the Anthology ever made are the Latin renderings of select epigrams by Hugo Grotius. They have not been printed separately, but will be found in Bosch and Lennep's edition of the Planudean Anthology, in the Didot edition, and in Dr Wellesley's Anthologia Polyglotta.

The number of more or less professed imitations in modern languages is very large, that of actual translations less considerable. F. D. Dehèque's French prose translation, however (1863), is valuable. The German language admits of the preservation of the original metre -- a circumstance advantageous to the German translators, Herder and Jacobs.

Robert Bland, Charles Merivale, and their associates (1806-1813), are often diffuse. Francis Wrangham's (1769–1842) versions are more spirited; and John Sterling's translations of the inscriptions of Simonides deserve high praise. Professor Wilson (Blackwood's Magazine, 1833-1835) collected and commented upon the labours of these and other translators, but included indifferent attempts of William Hay.

In 1849 Dr Henry Wellesley, principal of New Inn Hall, Oxford, published his Anthologia Polyglotta, a collection of the translations and imitations in all languages, with the original text. In this appeared some admirable versions by Goldwin Smith and Merivale, which, with the other English renderings extant at the time, accompany the literal prose translation of the Public School Selections, executed by the Rev. George Burges for Bohn's Classical Library (1854).

In 1864 Major R. G. Macgregor published an almost complete translation of the Anthology, a work whose stupendous industry and fidelity almost redeem the general mediocrity of the execution. Idylls and Epigrams, by Richard Garnett (1869, reprinted 1892 in the Cameo series), includes about 140 translations or imitations, with some original compositions in the same style.

Further translations (selections) are:

J. W. Mackail, Select Epigrams from the Greek

Anthology (with text, introduction, notes, and prose translation), 1890,

revised 1906, a most charming volume

Graham R. Tomson (Mrs Marriott Watson), Selections from the Greek Anthology

(1889)

W. H. D. Rouse, Echo of Greek Song (1899)

L. C. Perry, From the Garden of Hellas (New York, 1891)

W. R. Paton, Love Epigrams (1898).

Daryl Hine, "Puerilities: Erotic Epigrams of The Greek Anthology" (Princeton UP, 2001)

An agreeable little volume on the Anthology, by Lord Neaves, is one of Collins's series of Ancient Classics for Modern Readers. The Earl of Cromer found time to translate and publish an elegant volume of selections (1903).

Two critical contributions to the subject are the Rev. James Davies's essay on Epigrams in the Quarterly Review (vol. cxvii.), especially valuable for its lucid illustration of the distinction between Greek and Latin epigram; and the brilliant disquisition in J. A. Symonds's Studies of the Greek Poets (1873; 3rd ed., 1893).

List of Poets in Greek Anthology

Adaeus

Agathias

Agis

Alpheus Mytilenaeus

Ammianus

Antipater of Sidon

Antipater of Thessalonica

Antiphilus

Anyte of Tegea

Apollonides

Asclepiades of Samos

Asclepiodotus

Archias

Argentarius (Marcus)

Callimachus

Claudius Ptolemaeus

Crinagoras of Mytilene

Demodocus of Leros

Eratosthenes

Glaucus

Gregory of Nazianzus

Leonidas of Tarentum

Lucian of Samosata

Lucilius

Meleager of Gadara

Mnasalcas

Moschus

Myrinus

Nicaenetus of Samos

Nicarchus

Palladas

Pamphilus

Paulus Silentiarius

Perses

Philippus of Thessalonica

Philodemus

Plato

Rhianus

Rufinus

Satyrus

Simonides of Ceos

Straton of Sardis

Theocritus

Thymocles