Lessico

Armadillo

comune

Dasypus novemcinctus

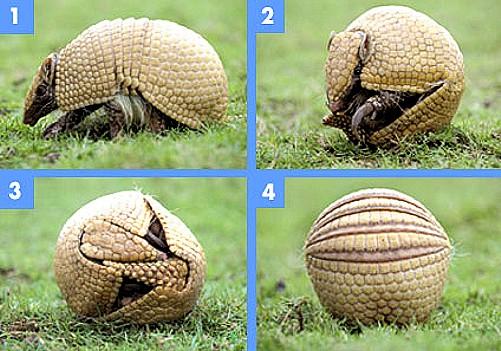

L'armadillo comune (Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus, 1757), detto anche armadillo a nove fasce, appartiene ai Mammiferi Maldentati, incluso nell'ordine degli Sdentati o Xenartri, famiglia Dasypodidae, diffuso nell'America Centro-Meridionale. Dasýpous in greco significa dai piedi pelosi e nell'antichità era un termine affibbiato alla lepre e al coniglio. Dasypus deriva dalla traduzione in greco del termine azteco Azotochtli con cui veniva identificato l'animale, che approssimativamente significava tartaruga-coniglio. Armadillo (attestato dal 1614, ma senz'altro anteriore), deriva dallo spagnolo armado = armato: detto così perché ha la testa e il tronco protetti da un'armatura articolata formata di placche ossee rivestite da squame cornee disposte in modo da permettere l'avvolgimento a palla dell'animale in caso di pericolo.

Ha il corpo ricoperto da piccole placche non saldate tra loro, che compongono la corazza entro cui l'armadillo si chiude a palla se è attaccato. Le zampe sono molto corte, ma robuste e provviste di unghioni. È un animale notturno, che scava lunghe gallerie nel terreno. Si nutre prevalentemente di formiche, coleotteri e altri artropodi ma anche di piccoli rettili e anfibi nonché di uova. Occasionalmente può integrare la dieta con frutti e bacche.

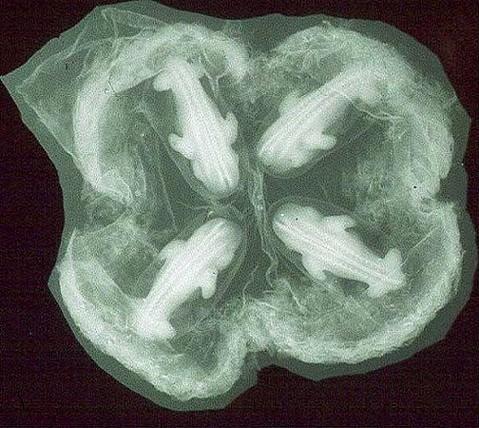

Nell'emisfero settentrionale l'accoppiamento avviene nel periodo tra luglio e agosto. Dopo una gestazione di circa 120 giorni e solo nella primavera successiva la femmina dà alla luce quattro cuccioli dello stesso sesso, sviluppatisi da un singolo uovo (gemelli monozigoti) e quindi identici sotto il profilo genetico.

Ecco la sequenza di questa trovata della natura: un solo uovo è fecondato in luglio/agosto, ma il suo impianto in utero è differito di 3-4 mesi per assicurare alla prole di nascere nella futura primavera. Dopo questi 3-4 mesi di attesa, in novembre lo zigote si impianta nell'utero ed ecco che inizia un periodo di gestazione di 4 mesi, all'inizio del quale lo zigote allo stadio di blastula si suddivide in quattro embrioni identici, ognuno dei quali sviluppa la propria placenta, cosicché il loro circolo sanguigno rimane indipendente.

Che dire poi dell'armadillo meridionale

(Dasypus hybridus![]()

![]() , fenotipicamente assai simile al Dasypus septemcinctus) diffuso

nella zona fra Argentina centro-settentrionale e Brasile meridionale: i

gemelli monozigoti sono in media 8, con oscillazioni che da 7 possono salire a

12.

, fenotipicamente assai simile al Dasypus septemcinctus) diffuso

nella zona fra Argentina centro-settentrionale e Brasile meridionale: i

gemelli monozigoti sono in media 8, con oscillazioni che da 7 possono salire a

12.

I piccoli si rendono autonomi dalla madre dopo poche settimane di vita e raggiungono la maturità sessuale intorno al primo anno di vita. L'aspettativa di vita è di 15-20 anni.

È presente in un vasto areale che va dal nord dell'Argentina e dell'Uruguay sino alla parte meridionale degli Stati Uniti d'America. Molti lo cacciano per nutrirsi della sua carne, mentre la corazza viene trasformata in utensili di vario uso.

Implantation

in the Nine-banded Armadillo.

How does a single blastocyst form four embryos?

In the course of a study on reproduction in the nine-banded armadillo, conceptuses between the beginning of implantation and primitive streak formation were examined to determine the manner of trophoblast differentiation during invasion of the endometrium and the sequence involved in formation of four identical quadruplets. The armadillo blastocyst implants in the fundic recess of the uterus. A single amnion and cup-shaped epiblastic plate are formed, and an exocelom develops between the amnion and trophoblast of the implantation site. Loss of the abembryonic trophoblast exposes both visceral and parietal endoderm to the uterine lumen, inverting the yolk sac. Continued expansion of the exocelom facilitates the intrusion of the forming conceptus into the uterine lumen and is accompanied by enlargement of the epiblastic plate. Separate areas of condensations of epiblast cells are the first indication of formation of the four identical quadruplets. The single layer of microvillous trophoblast with basal infoldings (designated absorptive trophoblast) is most likely to contribute extensively to movement of fluid into the exocelom. The resulting expansion of the exocelom not only enlarges the implantation site but also displaces the collapsing common amnion, limiting the amnion to the areas of the forming embryos.

Nine-banded Armadillo

Dasypus novemcinctus

Order: Xenarthra (Edentata) - Family: Dasypodidae. The nine bands that characterize this species are made of scutes, modified skin with bone marrow within. They are connected by loose connective tissue. The abdomen is made of a tough skin, with numerous hairs. Armadillos are South American species, and this form extends from Texas to Uruguay/Paraguay. By being insectivorous, it is limited largely by freezing temperatures in the North. Breeding of nine-banded armadillos in captivity has so far not been uniformly achieved. They are, however, prolific in the wild and are easily maintained in captivity. Thus, no captive "colonies" exist; some animals are being held in zoos of course. They are prized food items in many countries and popular armadillo races are commonly held in Texas.

In nature, the nine-banded armadillo extends from Argentina to Texas and it is

but one of about 20 species of armadillos. The nine-banded armadillo

represents the only armadillo species that immigrated from South America to

North America, approximately 2-3 million years ago. In the United States, it

is at home in Texas, Louisiana and, more recently, it has been introduced into

Florida. The home range in the United States was delineated by Buchanan (1958)

and, more recently, by Humphrey (1974). For Florida it was provided by Layne

& Glover (1977).

South of Uruguay, a similar species, the somewhat smaller (3,000 g)

seven-banded armadillo or mulita (Dasypus hybridus![]()

![]() ), regularly produces

between 8-12+ monozygotic multiple offspring. Both have a uterus simplex, in

contrast to most other armadillo species. They have also the same number and

appearance of chromosomes and could conceivably be subspecies. There are also

many specimens with intermediate numbers of bands (7-9) known. Species

delineation of the mulita (Dasypus hybridus) from the similarly

seven-banded species Dasypus septemcinctus is discussed at length by

Hamlett (1939) without, I feel, having come to a satisfactory answer. It is

also of interest that the shells of nine-banded armadillos are larger in the

equatorial regions, and half-bands are often seen. Thus, these may all be

merely races or incipient species. Broader considerations of Dasypodidae

were provided by Frechkop and Yepes (1949) and, of all armadillos, in the old

description of Gray (1973). Wetzel and Mondolfi (1979) provided a more

measured account of these species.

), regularly produces

between 8-12+ monozygotic multiple offspring. Both have a uterus simplex, in

contrast to most other armadillo species. They have also the same number and

appearance of chromosomes and could conceivably be subspecies. There are also

many specimens with intermediate numbers of bands (7-9) known. Species

delineation of the mulita (Dasypus hybridus) from the similarly

seven-banded species Dasypus septemcinctus is discussed at length by

Hamlett (1939) without, I feel, having come to a satisfactory answer. It is

also of interest that the shells of nine-banded armadillos are larger in the

equatorial regions, and half-bands are often seen. Thus, these may all be

merely races or incipient species. Broader considerations of Dasypodidae

were provided by Frechkop and Yepes (1949) and, of all armadillos, in the old

description of Gray (1973). Wetzel and Mondolfi (1979) provided a more

measured account of these species.

General gestational data

Nine-banded armadillos in Texas breed in July, and delayed implantation, with the blastocyst resting in the uterus, lasts for about 3-4 months. Implantation then takes place in November, with birth occurring in March/April. Ramsey (1982) gives the length of gestation as being 120-150 days, but that depends on what times exactly are counted. The adult nine-banded armadillo weighs between 4,000 and 5,000 g, newborns are 100 g.

This remarkable animal is the only known species that always produces monozygotic (identical) multiple offspring. Occasional quintuplets have been witnessed to occur. Quite frequently smaller numbers, such as singletons, twins and triplets have been described as well. Whether these are the result of fetal death is not known. Buchanan (1957) who examined 60 pregnant uteri found two animals with three embryos and no trace of a fourth. One uterus contained six embryos plus an additional amnionic sac. He referred to other records of odd numbers of embryos and later (1967), he described an uterus with a fundal implantation plus a blastocyst in the uterus. From this he inferred that only the fundal, cruciform depression of the uterus is fit to allow implantation of the placenta.

The reason for the unique "polyembryony" in Dasypodidae is not understood. The original assumption, that this was due to delayed implantation (3-4 months), was contradicted by Stockard (1921). While temporary hypoxia had been assumed to be the cause, Stockard suggested that it was an "innate ability" of the armadillo embryo that leads to "budding" of the embryonic disk. Even more prolonged delay in implantation (13-24 months) observed by Storrs et al. (1988) produced no change in the number of offspring. Other variations and the possible reasons for polyembryony are discussed by Galbreath (1985). Enders (2002) has recently addressed the possible mechanism leading to polyembryony in this species and provided a nice historical overview as well. While he laid the anatomical groundwork for explaining that polyembryony can feasibly occur in this species, the reason for embryonic "cloning" in armadillos is yet to be forthcoming.

Implantation

There is a single morula transported from the tube to the uterus where the developing blastocyst, with its thin inner cell mass, rests for months in a predestined depression in the fundus. The implantation is fundal with segregation of the placental disk by "budding" into four separate lobes that occurs after implantation. Therefrom develops a hemochorial placenta that attaches with a peripheral trabecular structure to the myometrium. Mossman (1987) speaks of this region as "many large endothelium-lined maternal blood spaces at the base of the placenta, and the distal portions of fetal villi often extend freely into these spaces. This arrangement is believed unique to the Dasypodidae but resembles the hematomes of carnivores". There is no decidua in my experience, although Mossman (1987) refers to the presence of decidua. The central, fundal location of the implantation site may be the result of converging endometrial grooves which Galbreath (1985) then related to the future development of polyembryony. It is here, where the blastocyst comes to lie and awaits its time for implantation.

In his very detailed description of early implantation of the armadillo and initial placental development, Enders (2002) does not consider that the "restriction" of the fundal fold is a cause of polyembryony. Rather, he suggested that the polyembryony may relate to several other factors. First, there is relative premature development of the placental membranes, as opposed to an expansion of the embryo. Then, with implantation, the abembryonic trophoblast rapidly degenerates and thus it leaves the also rapidly expanding exocoelom to be exposed to the uterine fluid, with potential absorption of glandular secretions. Also, there is an early inversion of yolk sac with subsequent polar atrophy. Enders showed that, initially, two embryos segregate from the embryonic shield, to be followed by a subsequent division, so that, ultimately, four embryos become reasonably uniformly deposited in the embryonic cavity.

The trophoblast is made up of an invasive portion that destroys endometrial glands, and an absorption group that, as Enders infers, must be interpreted as participating in fluid exchange because of its microvillous surface and dilated basal folds. One puzzling aspect of early placenta formation in the armadillo has been difficult to understand because it is so different from that of the best-studied human placenta. That is the origin of the mesothelial cells that form the future villous cores, as these are present long before there is the formation of a body wall and stalk (Enders, 2002). Perhaps cytogenetic or genetic studies can address this in the future.

The development of a large exocoelom is particularly striking, as is the peculiar arrangement of the amnion. There is only one amnionic cavity and, when the first two embryos form, the two amnions are connected by a tube that constricts, focally, the amnionic space. Ultimately these tubal connections between the amnionic sacs of the respective embryos are obliterated.

The placenta is villous, although Mossman (1987) considers it to be trabecular. The trabecular designation clearly derives from the solid peripheral solid strands of tissue shown above. This tissue is essentially the same as that in the giant anteater. I have more fully studied and described this region in the chapter on giant anteater. Both species are thus related in a vague way through this similarity in an unusual placentation. The "trabeculae", so it would appear to be in anteaters, represent peripheral extensions of villi, into which these may expand. They are made of connective tissue centers and plump trophoblast (probably not endothelium) covering them. A single corpus luteum only is always found in one or the other ovary during pregnancy in the nine-banded armadillo.

The placenta is grossly zonary but, individually the separate discs are "discoid" in character. There is a single chorion that carries the fetal blood vessels; but there are four individual amnionic sacs that enclose the fetuses and which are connected (with fluid-filled spaces) in the center of the disks during early stages of placentation.

Early

implantation with four disks.

The four amnions are centrally connected.

General characteristics of placenta

The end effect then is a slightly cotyledonary placenta with zonary shape, hemochorial in nature with a syncytial barrier to the intervillous space. There is no invasion of myometrium by wandering trophoblastic cells. In my opinion, in most places of the implanted armadillo placenta, the endometrium is lacking and the villi abut the myometrial sinusoids (with occasional myometrial trabeculae producing incomplete septa [Enders & Welsh, 1993] have a nice picture of these).

Initially there is cytotrophoblast from which the overlying syncytium originates. The typical cytotrophoblast degenerates or becomes so much less apparent so that, ultimately, only a thin layer of syncytium covers the villi. Few true "anchoring villi" are produced.

Normally there are four umbilical vessels, two arteries and two veins and no ducts. The length of the cords has not been measured or published. They are not spiraled. In a large number of umbilical cords studied, some numerical and errors in size of this vasculature were found (Benirschke et al., 1964).

The general vasculature of the uterus has not been described in detail. In letters, however, Enders (2002) pointed out to me that, first of all, trophoblast never touches the myometrial stroma but is always separated from the muscle by an endothelial layer of these vascular sinuses. Moreover, he stated that "one of the unusual features that has not been emphasized is that blood returning from the endometrial sinuses passes through a spongework of vessels around the more internal myometrial layers before reaching larger vessels". A normal, term pregnant uterus is here shown with some adjacent vessels.

The trophoblast of the free membranes degenerates soon after implantation. There is no decidua capsularis on the chorion laeve. There are large collections of compact trophoblast ("Träger") into which the connective tissue of the mesoderm and villous capillaries project initially. It contains numerous mitoses in early pregnancy but this region does not generally form anchoring villi. There is no true maternal vascular invasion by the trophoblast. Some of the Träger columns are attached to the basal myometrial spongy network, the only locus where the maternal endothelium is defective (Ramsey, 1982).

There is no real decidua at the base of the placenta, which has the villi attached to a spongy (?)myometrial layer of sinusoids. Mossman (1987) speaks of decidua, however, we have not been able to see it and Ramsey also denied its presence.

There are no other endometrial features of significance. Galbreath (1985) suggested that the four uterine folds that are present lead to the "nesting" of the initial blastocyst at the fundal depression and that this was related to the polyembryony. I have noted above, however, the reasons why Enders (2002) disagrees with that concept, as the folds are too soft and could readily be pushed aside by an expanding blastocyst. The endometrial space of the fundus, occupied by the blastocyst in early stages (these folds essentially retain the blastocyst), basically prevents the embryo from being moved into the uterus during the long stage before implantation occurs. It is unknown how the placenta detaches from the spongy surface of the myometrium and how the endometrium regenerates subsequently.

Endocrinology

A single corpus luteum is present in either ovary and persists through pregnancy. Progesterone is present during preimplantation stage, becomes elevated immediately after implantation and later falls in gestation when the placenta contains progesterone (Labhsetwar & Enders, 1968). Peppler & Stone (1980) determined the progesterone levels from blood. He found elevation to occur after implantation and to remain at the same level (20 ng/ml) until term. The follicular development has been described by Peppler & Canale (1980).

The fetal adrenal glands have a typical "fetal zone" similar to that of primates. Its function has been investigated by Brinck-Johnsen et al. (1967). It has been found that the presumed reason for problems associated with captive propagation is an adrenal-induced steroid change (Rideout et al., 1985).

The circadian rhythm and rhythmic melatonin studies were reviewed by Phillips et al. (1984) who described the epiphysis (pineal gland). Strauss (1981) reported that the pituitary gland contains more LH during the period of delayed implantation than nonpregnant animals.

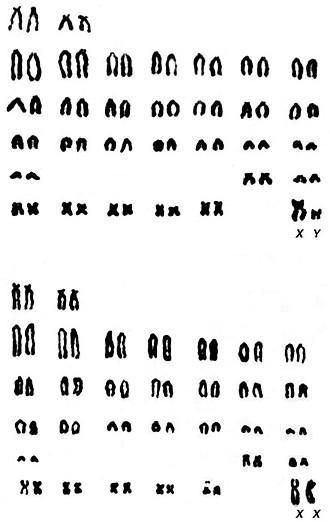

Genetics

Karyotypes of male and female nine-banded armadillo

Both species of Dasypodidae have 64 chromosomes, with 18 metacentrics, 44 acrocentric elements, a submetacentric X and an acrocentric Y chromosome. Hybrids are unknown. Initial molecular characterization has been published by Prodöhl et al. (1996). They examined especially the dispersion of MZ litters and the question of inbreeding at the periphery of the animals' expansion. In a later presentation (Loughry et al., 1998) this group stated that the possible reason for the polyembryony might be the lodging of the blastocyst of the peculiarly-shaped uterus. That has been referred to above, but is extremely speculative and needs much more study. Besides, why four in this species while the mulita has so many more MZ embryos? But the investigators showed genetically that, indeed, the quadruplets are genetically identical ("clones" as they called them). Also, they did not distribute widely over several years (about 200 meters!). One should then anticipate that, ultimately, the gene pool might become considerably restricted.

The number of "scutes" that compose the bands is around 566 per animal. Its inheritance and variations observed were reported in an extensive publication by Newman and Patterson (1911). Storrs & Williams (1968) found considerable differences in many bodily parameters and chemical values of the newborn monozygotic quadruplets.

Immunology

Anderson & Benirschke (1963) believed that the MZ quadruplets were immunologically distinct and that inter-quadruplet skin rejection could occur. This was in error, as Billingham & Neaves (1980) later showed. Enders & Welsh (1993) have argued that there is little or only brief exposure in armadillo (primate and rodent) trophoblast to the maternal connective tissue and that this factor may be one reason for the lack of immunologic "rejection" of the genetically different embryonic structures.

Occasional

pregnancies result only in twins,

even singletons are seen occasionally for as yet unknown reasons.

Pathological features

A choriocarcinoma has been described after treatment of a female armadillo

with thalidomide ["Contergan" in Germany] (Marin-Padilla &

Benirschke, 1963). From studies by Storrs (1978) and others it has become

known that nine-banded armadillos are susceptible to infection with Mycobacterium

leprae![]() and can succumb with widespread lepromatous lesions. The disease

exists in the free-living armadillos of Louisiana and Texas but has not been

reported from South American specimens. Nevertheless, Storrs et al. (1975)

showed that mulitas and D. kappleri, another South American dasypodid

species can be infected with this organism experimentally.

and can succumb with widespread lepromatous lesions. The disease

exists in the free-living armadillos of Louisiana and Texas but has not been

reported from South American specimens. Nevertheless, Storrs et al. (1975)

showed that mulitas and D. kappleri, another South American dasypodid

species can be infected with this organism experimentally.

Nine-banded armadillo with leprosy lesions of abdomen

Many armadillos are hunted with dogs, and suffer tail wounds as a consequence. These become frequently a source of sepsis. The causative organism of Chagas' disease, Trypanosoma cruzi, has been identified in this species (Barreto et al., 1985) and the animal has been considered to be a reservoir for this agent. We have seen a widespread skin infection from the flea Tunga penetrans in a nine-banded armadillo from Paraguay. This originally South American flea has spread widely and affects humans as well. Smith & Procop (2002) described the details of the histopathology of skin biopsies from seven patients who had recently traveled to tropical climates. The histologic appearance of the flea is characteristic and well described in that contribution.

Physiological data

Dasypodid species have low body temperatures. Cuba-Caparó determined it to be between 29.5 and 32°C). They are susceptible to cold, perhaps especially so because of the exposed marrow in their scutes. Armadillos are also highly resistant to hypoxia (Scholander et al., 1943), a faculty that aids in burrowing and crossing streams whilst walking at the river beds. It makes it also difficult to anesthetize the animals with ether. Other, more distantly related species (Chaetophractus villosus) have seemingly similar abilities (Affanni et al., 1987). Basic chemistry profiles were given by Strozier et al. (1971), and Ebaugh & Benson (1964) determined that red cell survival was only 70-75 days.

Other aspects of interest and other needs for study

Adamoli et al. (2001) have recently studied the placentas of Chaetophractus villosus, Cabassous chacoensis, Tolypeutes matacus and Dasypus hybridus. All of these species had a hemochorial placenta with a "pear-shaped" macroscopic appearance.

Nine-banded armadillo

The nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), or the nine-banded long-nosed armadillo (and colloquially as the poor man’s pig or poverty pig), is a species of armadillo found in North, Central, and South America, making it the most widespread of the armadillos. Its ancestors originated in South America and remained there until 3 million years ago when the formation of the Isthmus of Panama allowed them to enter North America during the Great American Interchange. The nine-banded long-nosed armadillo is a solitary, mainly nocturnal animal, found in many kinds of habitats, from mature and secondary rainforests to grassland and dry scrub. It is an insectivorous animal, feeding chiefly on ants, termites, and other small invertebrates. The armadillo can jump three to four feet (90–120 cm) straight in the air if sufficiently frightened, making it a particular danger on roads.

The nine-banded armadillo evolved in a warm rainy environment and is still most commonly found in regions resembling its ancestral home. However, it is a very adaptable animal that can also be found in scrublands, open prairies, and tropical rainforests. They cannot thrive in particularly cold or dry environments, as their large surface area, which is not well insulated by fat, makes them especially susceptible to heat and water loss.

The nine-banded armadillo has been rapidly expanding its range both north and east within the United States. The armadillo crossed the Rio Grande from Mexico in the late 1800’s and introduced in Florida at about the same time by humans. By 1995 the species had become well-established in Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, and had been sighted as far afield as Kansas, Missouri, Tennessee, Georgia and South Carolina. A decade later, the armadillo had become established in all of those areas and continued its migration, being sighted as far north as southern Nebraska, southern Illinois, and southern Indiana. The primary cause of this rapid expansion is explained simply by the existence of few or no natural predators of the armadillo within the United States, little desire on the part of Americans to hunt or eat the armadillo, and the animal's high reproductive rate. It is speculated that the northern expansion of the armadillo will continue until the species reaches as far north as Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey and all points southward on the East Coast of the United States. Further northward and westward expansion will probably be limited by the armadillo's poor tolerance of harsh winters, due to its lack of insulating fat and its inability to hibernate. As of 2008, newspaper reports indicate that the nine-banded armadillo seems to have expanded its range northward as far as Lincoln, Nebraska in the west, and Nashville, Tennessee and the Land Between the Lakes region as far north as Kentucky Dam and Evansville, Indiana in the east. Outside the United States, the nine-banded armadillo ranges southward through Central and South America into northern Argentina and Uruguay, where it is still expanding its range.

Nine-banded armadillos are generally insectivores. They forage for meals by thrusting their snouts into loose soil and leaf litter and franticly digging in erratic patterns, stopping occasionally to dig up grubs, beetles, ants, termites, and caterpillars, which their sensitive noses can detect through six inches of soil. They then lap up the insects with their sticky tongue. They supplement their diet with amphibians, small reptiles, fungi, tubers, and carrion.

Nine-banded armadillos weigh 12–22 lbs (5–9.5 kgs). Head and body length is 15–23 inches (37–57 cm), which combines with the 5–19 inches (12–46 cm) tail for a total length of 20–42 inches (50–105 cm). They stand 6–10 inches (15–25 cm) tall. The outer shell is composed of ossified dermal scutes covered by nonoverlapping, keratinized epidermal scales, which are connected by flexible bands of skin. This armor covers the back, sides, head, tail, and outside surfaces of the legs. The underside of the body and the inner surfaces of the legs have no armored protection. Instead, they are covered by tough skin and a layer of coarse hair. The vertebrae are specially modified to attach to the carapace. The claws on the middle toes of the forefeet are elongated for digging, though not to the same degree as those of the much larger giant armadillo of South America. Their low metabolic rate and poor thermoregulation make them best suited for semi-tropical environments. Unlike the South American three-banded armadillo, the nine-banded armadillo cannot roll itself into a ball. It is, however, capable of floating across rivers by inflating its intestines, or by sinking and running across riverbeds. The second is possible due to its ability to hold its breath for up to six minutes, an adaptation originally developed for allowing the animal to keep its snout submerged in soil for extended periods while foraging. Although nine is the typical number of bands on the nine-banded armadillo, the actual number varies by geographic range. Armadillos possess the teeth typical of all sloths, anteaters, and armadillos. The teeth are all small peg-like molars with open roots and no enamel. Incisors do form in the embryos, but quickly degenerate and are usually absent by birth.

Nine-banded armadillos are solitary, largely nocturnal animals that come out to forage around dusk. They are extensive burrowers, with a single animal sometimes maintaining up to 12 burrows on its range. These burrows are roughly 8 inches (20 cm) wide, 7 feet (2.1 m) deep, and 25 feet (7.5 m) long. Armadillos mark their territory with urine, faeces, and excretions from glands found on the eyelids, nose, and feet. Females tend to have exclusive, clearly defined territories. Males have larger territories, but theirs often overlap, and can coincide with the ranges of several females. Territorial disputes are settled by kicking and chasing. When they are not foraging, armadillos shuffle along fairly slowly, stopping occasionally to sniff the air for signs of danger. If alarmed, they can flee with surprising speed. If this method of escape fails, the armadillo may quickly dig a shallow trench and lodge itself inside. Predators are rarely able to dislodge the animal, and abandon their prey when they cannot breach the armadillo’s armor.

Mating takes place during a 2–3 month long mating season, which occurs from July-August in the Northern Hemisphere and November-January in the Southern Hemisphere. A single egg is fertilized, but implantation is delayed for 3–4 months to ensure the young will not be born until the spring. Once the zygote does implant in the uterus, there is a gestation period of four months during which the zygote splits into four identical embryos, which each develop their own placenta so blood and nutrients are not mixed between them. After birth, the quadruplets remain in the burrow, living off the mother’s milk for approximately three months. They then begin to forage with the mother, eventually leaving after six months to a year. Nine-banded armadillos reach sexual maturity at one year of age and reproduce every year for the rest of their 12–15 year lifespan. A single female can produce up to 56 young over the course of her life. This high reproductive rate is a major cause of the species’ rapid expansion.

The foraging of nine-banded armadillos can cause mild damage to the root systems of certain plants, but they make up for their disruptive habits by providing homes for skunks, cotton rats, burrowing owls, and rattlesnakes, all of which can be found living in abandoned armadillo burrows.

Nine-banded armadillos are sometimes hunted for their meat, which is said to taste like pork, but are more frequently killed as a result of their tendency to steal the eggs of poultry and game birds. This has caused certain populations of the nine-banded armadillo to become threatened, although the species as a whole is under no immediate threat. They are also valuable for use in medical research, as they are one of the few animals susceptible to the human disease leprosy. In Texas, nine-banded armadillos are raised to participate in armadillo racing, a small-scale, but well-established sport in which the animals scurry down a forty-foot track.

During the Great Depression, the species was hunted for its meat in East Texas, where it was known as "Hoover Hog" by those who considered President Herbert Hoover to be responsible for the depression. Earlier, German settlers in Texas would often refer to the armadillo as Panzerschwein ("armored pig"). In 1995, the nine-banded armadillo was, with some resistance, made the state small mammal of Texas, where it is considered a pest and is often seen dead on the roadside. They first forayed into Texas across the Rio Grande from Mexico in the 1800s, eventually spreading across the southeast United States.

Subspecies

Dasypus novemcinctus aequatorialis

Lönnberg, 1913

Dasypus novemcinctus fenestratus

Peters, 1864

Dasypus novemcinctus hoplites

G.M. Allen, 1911

Dasypus novemcinctus mexianae

Hagmann, 1908

Dasypus novemcinctus mexicanus

Peters, 1864

Dasypus novemcinctus novemcinctus

Linnaeus, 1758

North American subspecies exhibit reduced genetic variability compared with the subspecies of South America, indicating that the armadillos of North America are descended from a relatively small number of individuals that migrated from south of the Rio Grande.

Genus

Dasypus

Long-nosed armadillos

Six species of naked-tailed armadillos are recognized. The most familiar of these (and the most widespread of any armadillo species) is the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). The other five are the great long-nosed armadillo (Dasypus kappleri), the hairy long-nosed armadillo (Dasypus pilosus), the Llanos long-nosed armadillo (Dasypus sabanicola), the seven-banded armadillo (Dasypus septemcinctus), and the Southern long-nosed armadillo (Dasypus hybridus). A seventh species, Yepes's mulita (Dasypus yepesi) has been proposed based on some specimens from the Jujuy and Salta provinces of Argentina, but to date insufficient taxonomic data exists to confirm the existence of these animals as a distinct species.

Dasypus novemcinctus

Nine-banded Armadillo - Long-nosed Armadillo

Range: South-central and southeastern United States to Peru and Uruguay,

Grenada in the Lesser Antilles, Trinidad and Tobago.

Head and body length: 240 — 573 mm (9.4 — 22.6 in).

Tail length: 125 — 483 mm (4.9 — 19.0 in).

Weight: 1 — 10 kg (2.2 — 22.0 lbs).

Most members of the genus Dasypus have very little hair. Almost no hair is present on the upper part of the body, while sparsely scattered and pale yellowish hair is present on the undersides. They range from mottled brown to yellowish white in carapace color. Members of this genus are characterized by the long, pointed nose and relatively short legs. Four toes are present on the front feet, five toes on the hind feet, all with well-developed claws. Because they walk on the tips of their feet, they tend to leave three-toed tracks that resemble bird footprints. They may possess from 6 to 11 moveable bands on the shell. Dasypus novemcinctus generally has 8 bands in northern and southern parts of its range, and 9 bands in more central areas. The ears and tail of Dasypus novemcinctus are very long. The ears may be 40 to 50% of the length of the head, and the tail is around 70% of the length of the body.

Members of this genus appear to prefer dense shady cover and limestone formations, from sea level to 3000 meters in elevation. They dig burrows from 0.5 to 3.5 meters deep and up to 7.5 meters long. Large nests of grass or leaves are often constructed in nest chambers within the burrow. Dasypus novemcinctus has been observed to build nests outside of burrows, in clumps of saw palmetto, resembling small haystacks. They often share burrows with other armadillos, but not with members of the opposite sex.

Armadillos in the genus Dasypus are primarily nocturnal, but occasionally forage in the daytime. They emit almost constant grunting noises while they are foraging. If they feel threatened, they hurry to a nearby burrow. If there is no burrow nearby, they curl up as much as possible to protect their soft undersides. The animals do not seem to feel threatened by humans.

The diet consists primarily of animal matter, but is adaptable based on foraging conditions. In areas with little insect prey but large amounts of berries or other plant material, the nine-banded armadillo will readily switch to a more vegetarian diet. The armadillos forage for insects, spiders, and small amphibians; they predominately seem to prefer beetles and ants. They have been known to kill and eat young cottontail rabbits, and are also known to eat scraps of carrion. Although the nine-banded armadillo is often accused of eating the eggs and young of ground nesting birds such as quail, birds and their eggs make up less than 0.4% of the diet of an average armadillo. Nine-banded armadillos have a salivary bladder surrounded by skeletal muscle, unique among mammals. The salivary bladder acts as a reservoir for the thick, sticky saliva used to capture small insects. When the armadillo is feeding, the muscles around the salivary bladder contract, squeezing the stored saliva out onto the tongue.

The average home range of 12 Dasypus novemcinctus studied in Florida is 5.7 hectares (12.4 acres). Population densities in South America have been reported as high as 13 per square kilometer for Dasypus novemcinctus. Dasypus novemcinctus has been reported to be aggressive in high densities, and are frequently seen chasing or “boxing” one another by balancing on the hind legs and tails and striking out with the front claws. Adult males were more aggressive towards subadult males; lactating or pregnant females were aggressive towards young born the previous year.

Mating in North America takes place in July and August, but implantation of the zygote is delayed until November. The gestation period is 120 days. Dasypus novemcinctus is unique in that four identical young are produced from a single egg, producing litters of four identical young (although occasionally only two to three or as many as six young have been found in a single litter). Young are born with their eyes open, are weaned at 4 — 5 months, and are sexually mature at about 1 year of age. Females have four mammae, one for each armadillo pup. The life span of Dasypus novemcinctus is reported to be 12 to 15 years.

Dasypus novemcinctus is the only Xenarthran found in the United States. They are relatively recent arrivals, having expanded their range into Texas around 1880. Dasypus novemcinctus was introduced into Florida deliberately in the 1920’s. The nine-banded armadillo has expanded its range as far northwest as Colorado, and currently is also found in Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, South Carolina and Georgia. Members of the genus Dasypus have been present in what is now the US intermittently for about one million years. The last animal of this genus to live in central North America was Dasypus bellus, the beautiful armadillo, during the Pleistocene era, occupying basically the same range as Dasypus novemcinctus does today. Dasypus bellus is considered the historical counterpart of the nine-banded armadillo, as they are identical except for size.

Dasypus novemcinctus has been accused of destroying eggs, burrowing under foundations, and crop destruction. Members of the genus Dasypus are generally considered to be ecologically important due to their destruction of unwanted insects. Many other small animals use abandoned armadillo burrows as shelter. Dasypus novemcinctus is easily tamed, but does not appear to do well in captivity. Due to the unique production of four identical young, weak immune system and relatively low body temperatures, Dasypus novemcinctus has proven useful as a medical research test animal for diseases such as leprosy, typhus, and trichinosis, as well as for research on multiple births, organ transplants, and birth defects. Nine-banded armadillos carry relatively few parasites, despite the lack of a strong immune response. Dasypus novemcinctus is particularly noted for its susceptibility to leprosy, both in laboratories and in the wild. Dasypus novemcinctus is the most common armadillo held in zoos, especially in the US.

Dasypus

kappleri

Great Long-nosed Armadillo

Range: East of the Andes from Colombia and northern Bolivia to the Guianas and

northeastern Brazil.

Head and body length: 240 — 573 mm (9.4 — 22.5 in).

Tail length: 125 — 483 mm (4.9 — 19.0 in).

Weight: 1 — 10 kg (2.2 — 22.0 lbs).

Most members of the genus Dasypus have very little hair. Almost no hair is present on the upper part of the body, while sparsely scattered and pale yellowish hair is present on the undersides. They range from mottled brown to yellowish white in carapace color. Members of this genus are characterized by the long, pointed nose and relatively short legs. Four toes are present on the front feet, five toes on the hind feet, all with well-developed claws. They may possess from 6 to 11 movable bands on the shell. Dasypus kappleri has two to three rows of bony scutes on the knees, a trait not seen in other members of the genus Dasypus.

Members of this genus appear to prefer dense shady cover and limestone formations, from sea level to 3000 meters in elevation. They dig burrows from 0.5 to 3.5 meters deep and up to 7.5 meters long. Large nests of grass or leaves are often constructed in nest chambers within the burrow. They often share burrows with other armadillos, but not with members of the opposite sex.

Armadillos in the genus Dasypus are primarily nocturnal, but occasionally forage in the daytime. They emit almost constant grunting noises while they are foraging. If they feel threatened, they hurry to a nearby burrow. If there is no burrow nearby, they curl up as much as possible to protect their soft undersides. The animals do not seem to feel threatened by humans. The diet consists primarily of animal matter. The armadillos forage for insects, spiders, and small amphibians; they predominately seem to prefer beetles and ants. Dasypus kappleri produces 2 — 12 young per litter.

Dasypus pilosus

Hairy Long-nosed Armadillo

Range: found only in mountains of southwestern Peru.

Head and body length: 240 — 573 mm (9.4 — 22.6 in).

Tail length: 125 — 483 mm (4.9 — 19.0 in).

Weight: 1 — 10 kg (2.2 — 22.0 lbs).

Although most members of the genus Dasypus have very little hair, the hairy long-nosed armadillo is an exception to this rule. Almost no hair is present on the head, but long white and pale yellowish hair is present on the shell and undersides, giving this animal a distinctly furry appearance. They range from mottled brown to yellowish white in carapace color. Members of this genus are characterized by the long, pointed nose and relatively short legs. Four toes are present on the front feet, five toes on the hind feet, all with well-developed claws. They generally have 11 movable bands on the shell.

Members of this genus appear to prefer dense shady cover and limestone formations, from sea level to 3000 meters in elevation. They dig burrows from 0.5 to 3.5 meters deep and up to 7.5 meters long. Large nests of grass or leaves are often constructed in nest chambers within the burrow. They often share burrows with other armadillos, but not with members of the opposite sex.

Armadillos in the genus Dasypus are primarily nocturnal, but occasionally forage in the daytime. They emit almost constant grunting noises while they are foraging. If they feel threatened, they hurry to a nearby burrow. If there is no burrow nearby, they curl up as much as possible to protect their soft undersides. The animals do not seem to feel threatened by humans. The diet consists primarily of animal matter. The armadillos forage for insects, spiders, and small amphibians; they predominately seem to prefer beetles and ants.

Dasypus pilosus is listed as vulnerable by the IUCN, but other species in the genus Dasypus may be increasing in number. The hairy long-nosed armadillo is a protected species in Peru.

Dasypus sabanicola

Llanos Long-nosed Armadillo

Range: llanos of Colombia and Venezuela.

Head and body length: 240 — 573 mm (9.4 — 22.5 in).

Tail length: 125 — 483 mm (4.9 — 19.0 in).

Weight: 1 — 10 kg (2.2 — 22.0 lbs).

Most members of the genus Dasypus have very little hair. Almost no hair is present on the upper part of the body, while sparsely scattered and pale yellowish hair is present on the undersides. They range from mottled brown to yellowish white in carapace color. Members of this genus are characterized by the long, pointed nose and relatively short legs. Four toes are present on the front feet, five toes on the hind feet, all with well-developed claws. They may possess from 6 to 11 movable bands on the shell. The ears of Dasypus sabanicola are shorter than the ears of Dasypus novemcinctus.

Members of this genus appear to prefer dense shady cover and limestone formations, from sea level to 3000 meters in elevation. They dig burrows from 0.5 to 3.5 meters deep and up to 7.5 meters long. Large nests of grass or leaves are often constructed in nest chambers within the burrow. They often share burrows with other armadillos, but not with members of the opposite sex.

Armadillos in the genus Dasypus are primarily nocturnal, but occasionally forage in the daytime. They emit almost constant grunting noises while they are foraging. If they feel threatened, they hurry to a nearby burrow. If there is no burrow nearby, they curl up as much as possible to protect their soft undersides. The animals do not seem to feel threatened by humans. The diet consists primarily of animal matter. The armadillos forage for insects, spiders, and small amphibians; they predominately seem to prefer beetles and ants. Population densities in South America have been reported as high as 280 per square kilometer for Dasypus sabanicola. Dasypus sabanicola bears 4 young per litter.

Dasypus septemcinctus

Seven-banded Armadillo

Range: Eastern and southern Brazil, eastern Bolivia, Paraguay, extreme

northern Argentina.

Head and body length: 240 — 573 mm (9.4 — 22.5 in).

Tail length: 125 — 483 mm (4.9 — 19.0 in).

Weight: 1 — 10 kg (2.2 — 22.0 lbs).

Most members of the genus Dasypus have very little hair. Almost no hair is present on the upper part of the body, while sparsely scattered and pale yellowish hair is present on the undersides. They range from mottled brown to yellowish white in carapace color. Members of this genus are characterized by the long, pointed nose and relatively short legs. Four toes are present on the front feet, five toes on the hind feet, all with well-developed claws. They generally have 6 or 7 movable bands on the shell.

Members of this genus appear to prefer dense shady cover and limestone formations, from sea level to 3000 meters in elevation. They dig burrows from 0.5 to 3.5 meters deep and up to 7.5 meters long. Large nests of grass or leaves are often constructed in nest chambers within the burrow. They often share burrows with other armadillos, but not with members of the opposite sex.

Armadillos in the genus Dasypus are primarily nocturnal, but occasionally forage in the daytime. They emit almost constant grunting noises while they are foraging. If they feel threatened, they hurry to a nearby burrow. If there is no burrow nearby, they curl up as much as possible to protect their soft undersides. The animals do not seem to feel threatened by humans. The diet consists primarily of animal matter. The armadillos forage for insects, spiders, and small amphibians; they predominately seem to prefer beetles and ants. Dasypus septemcinctus may have 4 — 8 young per litter.

Dasypus hybridus

Southern Long-nosed Armadillo

Range: Paraguay, northern and central Argentina, Uruguay, southern Brazil.

Head and body length: 240 — 573 mm (9.4 — 22.5 in).

Tail length: 125 — 483 mm (4.9 — 19.0 in).

Weight: 1 — 10 kg (2.2 — 22.0 lbs).

Most members of the genus Dasypus have very little hair. Almost no hair is present on the upper part of the body, while sparsely scattered and pale yellowish hair is present on the undersides. They range from mottled brown to yellowish white in carapace color. Members of this genus are characterized by the long, pointed nose and relatively short legs. Four toes are present on the front feet, five toes on the hind feet, all with well-developed claws. They generally have 6 or 7 movable bands on the shell. The ears of Dasypus hybridus are shorter than the ears of Dasypus novemcinctus.

Members of this genus appear to prefer dense shady cover and limestone formations, from sea level to 3000 meters in elevation. They dig burrows from 0.5 to 3.5 meters deep and up to 7.5 meters long. Large nests of grass or leaves are often constructed in nest chambers within the burrow. They often share burrows with other armadillos, but not with members of the opposite sex.

Armadillos in the genus Dasypus are primarily nocturnal, but occasionally forage in the daytime. They emit almost constant grunting noises while they are foraging. If they feel threatened, they hurry to a nearby burrow. If there is no burrow nearby, they curl up as much as possible to protect their soft undersides. The animals do not seem to feel threatened by humans. The diet consists primarily of animal matter. The armadillos forage for insects, spiders, and small amphibians; they predominately seem to prefer beetles and ants. In Dasypus hybridus, implantation of the zygote occurs in June, and young are born in October, 4 — 12 young per litter.

Armadillo

meridionale

Dasypus hybridus

L'armadillo meridionale (Dasypus hybridus) è un armadillo diffuso nella zona fra Argentina centro-settentrionale e Brasile meridionale, dove vive nelle zone erbose o semiboschive. Misura fino a 90 cm di lunghezza (circa metà dei quali è costituita dalla coda), per un peso che può raggiungere i 10 kg. È molto simile all'armadillo a 9 fasce, rispetto al quale ha però orecchie più arrotondate e colori generalmente più scuri.

Dasypus hybridus

Dasypus hybridus (Desmarest 1804): Class Mammalia; Subclass Theria; Infraclass Eutheria; Order Cingulata; Family Dasypodidae; Subfamily Dasypodinae (Myers et al 2006, Möller-Krull et al 2007). Seven species are recognised in this genus, three are present in Paraguay. Dasypus is derived from a Greek translation of the Aztec name "Azotochtli" which roughly means "tortoise-rabbit"; hybridus means "hybrid", presumably in reference to the supposedly "hybrid-appearance" of the species between either a tortoise and a rabbit, or else a tortoise and a mule (from Spanish common name "mulita"). The synonymy with Dasypus septemcinctus below refers to a period when the two species were regularly confused in the literature. This species is monotypic. Desmarest´s original description was based on "Le Tatou Mulet" of de Azara (1801).

"Long-nosed" Armadillos have a broad, depressed body, an obtusely-pointed rostrum, long, pointed ears and short legs. The carapace consists of two immobile plates, the scapular and pelvic shields separated by 6 or 7 movable bands connected to each other by a fold of hairless skin. The carapace is mostly dull brownish-grey to brownish-yellow, distinctly paler than other Paraguayan Dasypus and with a very light covering of hair. Frequently there is a paler yellowish lateral line that is more visible in some individuals than others. The scales of the anterior edge of the movable bands are darker than the rest of the dorsum. Scutes on the movable bands are triangular in shape, but those on the main plates are rounded. The number of scutes present on the fourth movable band varies from 50 to 62, with a mean of 54 (Diaz & Barquez 2002, Hamlett 1939). The head is thin and triangular with a sloping forehead and long, mobile ears with rounded tips that are not separated by armour at the base. The tail is short compared to other Dasypus (60-70% body length), broad at the base and narrowing towards the tip. There are four toes on the forefeet (characteristic of the Subfamily Dasypodinae), the middle two much the longest, and five on the hindfeet. The underside is naked and pink-grey. Females possess four mammae. CR: Steeply descending frontal bone. DF: Armadillos lack true teeth. "Long-nosed" armadillos have single-rooted, peg-like teeth that lack enamel. Dental formula 6/8=28. CN: 2n=64. FN=76. (Gardner 2007).

Dasypus prints can be distinguished from those of other armadillos by their long, pointed toes with four toes on the forefoot and five on the hindfoot. However they generally leave the impression of only the two central toes on the forefeet (though sometimes the outer toe is also visible) and three central toes on the hindfeet. Given a full print, the hindfoot has a pointed heel with three long, somewhat pointed central toes and two, much shorter, outer toes set well back towards the heel. The forefoot has the inner toe much reduced and it rarely leaves an impression.

This species is intermediate in size between the other two "long-nosed armadillos" in Paraguay and is characterised by its shorter ears (25-30% of head length) and tail (67-70% of body length) which give it a distinctive appearance. Furthermore it is paler in colouration than both the other species, being distinctly brownish-yellow overall. It can be immediately separated from the much larger and more widespread Dasypus novemcinctus by the number of bands - 6 or 7 as opposed to eight or nine (usually 8) in that species (Hamlett 1939). Note also that the tail length of Dasypus novemcinctus is equal to or greater than the body length and that the ears are much longer (40-50% of head length). Dasypus novemcinctus has 7 to 9 teeth in the upper jaw, typically 8, compared to 6 in this species. Using the fourth movable band as a standard, Hamlett (1939) noted that this species has a mean of 54 scutes whereas Dasypus novemcinctus has a mean of 60 scutes. Furthermore this species prefers open country habitats, whereas Dasypus novemcinctus is more often associated with forested areas. The other open-country Dasypus is the smaller and darker Dasypus septemcinctus, but it is unclear exactly how much their ranges overlap in Paraguay or even if they do at all. It would seem that Dasypusseptemcinctus is perhaps more likely to be encountered in the north of the country and this species in the south. Dasypus septemcinctus shares the number of movable bands and number of teeth in the upper jaw with this species, but is clearly longer-eared (40-50% head length) and longer tailed (80-100% body length). Dasypus septemcinctus has a mean of 48.4 scutes along the fourth movable band (Hamlett 1939).

The most southerly of the Dasypus armadillos, with an extensive range from Argentina through Uruguay in the east to Brazil, probably as far north as Mato Grosso do Sul. However the species is apparently absent or un-recorded in many areas of the vast range and the maps given by Redford & Eisenberg (1992) incorrectly exaggerate the extent of the species distribution in Brazil and Argentina. In Argentina it is found east only as far as eastern Provincia Cordoba in Argentina and south to Provincia Buenos Aires, with records for the Andean foothills being the result of mis-identification. Though it has been cited as present in Provincia Misiones, Argentina there is apparently no confirmation of the species occurrence there (Chebez 2001) and there are only two records with an imprecise locality from Jujuy both collected in the 1930s (Diaz & Barquez 2002). In Paraguay its precise range is uncertain because of confusion over the species identity. Neris et al (2001) mapped both this species and that of the Seven-banded together, reflecting the lack of clarity in the range of the two species. However it would seem that Southern Long-nosed is more likely to be found in the south of the country, north perhaps as far as southern Departamento Candideyú. It has not been found in the Mbaracayú Biosphere Reserve, though Seven-banded does occur there and there are no records of either species in the south-west of Paraguay from Asunción south to Departamento Ñeembucú and much of Departamento Misiones. A species of undisturbed grasslands that does not tolerate human alteration of habitat, its distribution may have been naturally limited in Paraguay by the expanse of the Atlantic Forest and further reduced by human activity.

This species is typical of native, undisturbed grasslands and is unable to tolerate human interference, rapidly disappearing from agricultural areas (Edentate Specialist Group 2004).

Constantly on the move, this species feeds in much the same way as the Nine-banded Armadillo. moving rapidly and snuffling constantly when digging shallow foraging holes. In Uruguay they have been recorded as digging into ant and termite nests. One stomach contained mostly ants and termites as well as Orthoptera, Lepidoptera, other invertebrates and the remains of a small rodent, though it is unclear if that individual was hunted or scavenged. (Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Captive individuals were maintained on a daily diet of 100g high protein (26%) commercial puppy food soaked in water a day before presentation, 50mg powdered milk, water and 30g mince meat. This was supplemented with vitamins and minerals and an egg was added twice a week.(Ferrari et al 1997).

Ferrari et al (1997) published the first data on captive breeding of the species. They noted that the breeding cycle begins in March in Buenos Aires with the first copulations, with births in October and November. The male was not removed from the enclosure as it posed no threat to the offpring. Embryo counts range from 7 to 12, with 8 the most common number (Redford & Eisenberg 1992).

General Behaviour Solitary and active during the day and at night, though often more nocturnal in summer to avoid the heat of the day (González 2001). Captive individuals in Buenos Aires, Argentina were observed to be most active at midday during winter and in the afternoon during summer, remaining inactive during the hottest temperatures (Ferrari et al 1997). The main function of burrows is to provide refuge from predators and to provide shelter for resting (González et al 2001). Burrows are located only in open areas in grasslands and not in forested habitats. Typically they are around 1-2m long with a single entrance less than 25cm in diameter and dry grass may be accumulated at the entrance (González 2001). In Uruguay burrows were most frequently located in open areas with sandy soils on flat or sloping ground (89.3%), in ravines (5.1%) or amongst rocks (5.6%). (González et al 2001). Of the 20 excavated burrows studied the mean dimensions where length 118.8cm (+/-105.69cm), width 15.3cm (+/-5.15cm) and depth 43.3cm (+/-10.22cm). These burrows were approximately cylindrical with a conical end, consisting of a single tunnel without branches and in 6 cases terminating in a chamber 25.6cm (+/-6.19cm) wide x 35.2cm deep (+/-8.49cm). Burrows were randomly situated but the entrance avoided facing south, the direction of prevailing winds in the study area. The considerable difference in burrow lengths may be related to differences in usage . Burrows providing refuge from predators would be needed year round, and these would be likely to be more numerous, shorter burrows which are rapidly constructed and fulfil the function of providing safe haven. The qualities of resting burrows will likely vary through the year given the difference in summer and winter temperatures in Uruguay. During the cold winters longer and deeper burrows which maintain a higer temperature than the outside air help the animal thermoregulate. (González et al 2001). Defensive Behaviour When pursued they run rapidly and erratically towards their burrow. Parasites Navone (1990) recorded the following nematodes in this species in the Argentinean Pampas: Aspidodera fasciata (Aspidoderidae), Pterygodermatites chaetophracti (Rictularidae) and Mazzia bialata (Cosmocercidae) and Aspidodera fasciata (Aspidoderidae) in the Espinal region. Pterygodermatites chaetophracti (Rictularidae) and Mazzia bialata (Cosmocercidae) were also recorded in the Paranaense region. Snuffling noises are given when foraging.

Hunted throughout its range as a source of food. It is hunted in Uruguay and has been used in the fabrication of crafts since Prehispanic times, though only during the 20th Centruy did the pressure on the species begin to tell (Fallabrino & Castañeira 2006). No specific information is available for Paraguay where the species is extremely poorly known, but it is undoubtedly hunted for food and it is doubtful whether hunters would consciously distinguish this species from other Dasypus. The Southern Long-nosed Armadillo is considered Lowest Risk, near threatened by the IUCN, click here to see their latest assessment of the species. The Centro de Datos de Conservación in Paraguay do not list the species and nor is it listed by CITES. This species is more susceptible to human interference than other Dasypus and has disappeared over large areas of its range in Argentina as a result of the expanse of agriculture. It has undergone a notable decline and range contraction over the last thirty years as a result of hunting and habitat destruction and few of the areas with viable populations of the species are under official protection. The situation in Paraguay is unclear and its precise distribution is unknown as a result of confusion with other Dasypus. However, conversion of natural grasslands to agriculture in Paraguay has been equally rapid and the species has undoubtedly undergone a similarly silent decline in the country.