Lessico

San Bernardo di Chiaravalle

Santo, dottore della Chiesa, mistico e filosofo, detto Doctor mellifluus (Fontaines, Digione, 1090 o 1091 - Clairvaux 1153). È considerato il secondo fondatore dell'ordine dei Cistercensi (dal latino medievale. cisterciensis, da Cistercium, nome antico di Cîteaux, abbazia della Francia, nel comune di Saint-Nicolas-lès-Cîteaux dipartimento della Côte-d'Or dove nel 1098 da una ventina monaci benedettini con l'abate Roberto era stato fondato per la prima volta il Sacer Ordo Cistercensis), Cistercensi che da lui furono detti Bernardini.

Apparteneva a famiglia nobile e pia della Borgogna e venne educato dai canonici regolari. Nel 1112 entrò nell'abbazia di Cîteaux, il che rappresentò l'avvio per una splendida fioritura che vide in pochissimi anni la fondazione di quattro nuovi monasteri. Nel 1115 Santo Stefano Harding inviò Bernardo a fondare quel monastero che assunse il nome di Clairvaux (clara vallis, Chiaravalle), di cui Bernardo fu abate fino alla morte. Egli però percorse in continuazione tutta l'Europa esercitando un grande influsso religioso e anche politico su vescovi e principi.

Sostenne, per esempio, nel Concilio di Étampes (1130) papa Innocenzo II contro lo scismatico Anacleto II; accompagnò quindi il papa in Italia nel 1133 (e vi svolse opera di pacificazione tra Pisani e Genovesi) e nel 1135: data importante, oltre che per l'opera politica svolta a Milano, anche per la fondazione dell'abbazia milanese di Chiaravalle, che inaugurò tutta una serie di nuove fondazioni.

Bernardo si prefisse una propria riforma ecclesiastica contro Arnaldo da Brescia; costruì un proprio mistico cristocentrismo contro la teologia dialettica di Abelardo; combatté l'eresia dei Petrobrusiani. Su incarico del papa Eugenio III predicò nel 1146-47 in Francia la crociata per la liberazione dei luoghi santi. La sua predicazione fu tanto efficace che 200.000 uomini guidati da Corrado III e Luigi VII il Giovane presero le armi. La crociata però finì in modo disastroso.

Nel 1149 Bernardo iniziò il De consideratione libri V ad Eugenium III con un vasto piano di restaurazione della disciplina ecclesiastica. I numerosi scritti di Bernardo comprendono lettere, sermoni, trattati ascetico-mistici, monastici, liturgici, dogmatici, apologetici, agiografici: nel complesso una vera e propria somma di spiritualità. In campo politico Bernardo formulò la dottrina delle “due spade”, cioè del potere religioso e temporale, che assieme dovevano debellare le eresie e i pericoli per l'unità politica e condurre i sudditi cristiani al porto sicuro della concordia sociale e dell'unità nella fede.

Da un punto di vista filosofico, Bernardo insiste sulla cooperazione volontà-grazia nel processo di santificazione dell'uomo, che avviene con la mediazione del Cristo attraverso i gradi dell'umiltà e dell'amore. Il Doctor mellifluus ha esaltato anche Maria, che egli considera “mediatrice universale delle grazie”. Appassionato cultore del canto gregoriano, ne promosse una riforma per liberarlo da arbitrarie interpolazioni e ricondurlo alla sua originaria purezza. Fu canonizzato nel 1174. Festa il 20 agosto. I passi alpini valdostani del Piccolo San Bernardo (2188 m, Alpi Graie) e del Gran San Bernardo (2469 m, Alpi Pennine) sono dedicati a un altro santo, San Bernardo di Mentone (923-1008).

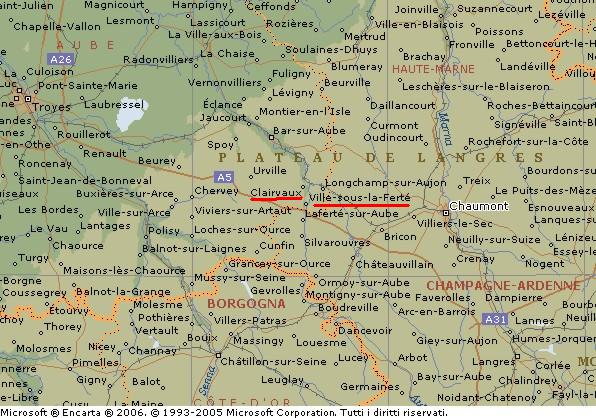

Clairvaux

- nel dipartimento dell'Aube,

frazione di Ville-sous-la-Ferté, 55 km a ESE di Troyes.

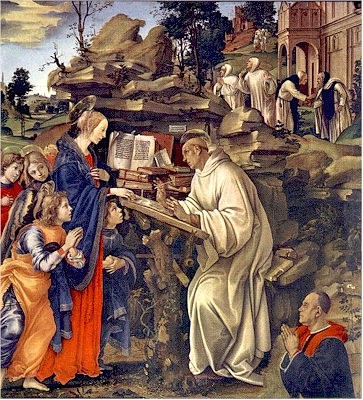

Bernardo di Chiaravalle

Apparizione

della Vergine a san Bernardo di Chiaravalle

Firenze - Badia fiorentina

Filippini Lippi (Prato 1457 - Firenze 1504)

Bernardo di Chiaravalle o Bernard de Clairvaux (Fontaine-lès-Dijon, 1090 – Ville-sous-la-Ferté, 20 agosto 1153) è stato un teologo e abate francese, fondatore della celebre abbazia di Clairvaux. Viene venerato come santo dalla Chiesa cattolica. Canonizzato nel 1174 da papa Alessandro III, fu dichiarato Dottore della Chiesa, Doctor Mellifluus, da papa Pio VIII nel 1830.

Biografia

Terzo di sette fratelli, nacque da Tescelino il Sauro, vassallo di Oddone I di Borgogna, e da Aletta, figlia di Bernardo di Montbard, anch'egli vassallo del duca di Borgogna. Studiò solo grammatica e retorica (non tutte le sette arti liberali, dunque) nella scuola dei canonici di Nôtre Dame di Saint-Vorles, presso Châtillon-sur-Seine, dove la famiglia aveva dei possedimenti.

La casa natale di Bernardo e la basilica

Ritornato nel castello paterno di Fontaines, nel 1111, insieme ai cinque fratelli e ad altri parenti e amici, si ritirò nella casa di Châtillon per condurvi una vita di ritiro e di preghiera finché, l'anno seguente, con una trentina di compagni si fece monaco nel convento cistercense di Cîteaux, fondato quindici anni prima da Roberto di Molesmes e allora retto da Stefano Harding.

Nel 1115, insieme a dodici compagni, tra i quali erano quattro fratelli, uno zio e un cugino, si trasferì nella proprietà di un parente, nella regione della Champagne, che aveva donato ai monaci un vasto terreno sulle rive del fiume Aube, nella diocesi di Langres perché vi fosse costruito un nuovo convento cistercense: essi chiamarono quella valle Clairvaux, chiara valle.

Ottenuta l'approvazione del vescovo Guglielmo di Champeaux e ricevute numerose donazioni, l'abbazia divenne in breve tempo un centro di richiamo oltre che di irradiazione: già dal 1118 monaci di Clairvaux partirono per fondare altrove nuovi conventi, come a Trois-Fontaines, a Fontenay, a Foigny, a Autun, a Laon; si calcola che nell'arco dei primi 40 anni furono sessantotto i conventi fondati da monaci provenienti da Chiaravalle.

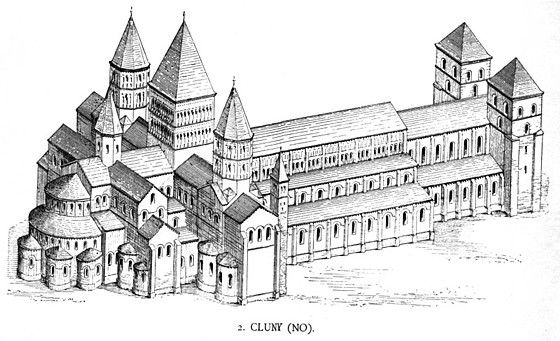

La polemica con Cluny

L'abbazia

di Cluny dipartimento di Saône-et-Loire,

20 km a NW di Mâcon, nella valle del fiume Grosne.

Nella Lettera 1, spedita verso il 1124 al cugino Roberto, Bernardo mostra di considerare la vita monastica dei benedettini di Cluny, allora all'apogeo del loro sviluppo, come un luogo che negava i valori della povertà, dell'austerità e della santità; egli rifiuta la teoria della regola benedettina della stabilitas - ossia del legame permanente e definitivo che dovrebbe stabilirsi fra monaco e monastero - sostenendo la legittimità del passaggio da un convento cluniacense a uno cistercense, essendovi in quest'ultimo professata una regola più rigorosa e più aderente alla Regola di San Benedetto, pertanto una vita monastica perfetta. La polemica fu da lui ripresa nell' Apologia all'abate Guglielmo, sollecitata da Guglielmo, abate del monastero di Saint-Thierry, che ebbe una risposta dall'abate di Cluny, Pietro il Venerabile, nella quale l'abate rivendicava la legittimità della discrezione nell'interpretazione della regola benedettina.

Nel 1130, alla morte di

Onorio II, furono eletti due papi: uno, dalla fazione della famiglia romana

dei Frangipane![]() , col nome di Innocenzo II e

un altro, appoggiato dalla famiglia dei Pierleoni, con il nome di Anacleto II;

Bernardo appoggiò attivamente il primo che, nella storia della Chiesa, per

quanto eletto da un minor numero di cardinali, sarà riconosciuto come

autentico papa, grazie soprattutto all'appoggio dei maggiori regni europei.

, col nome di Innocenzo II e

un altro, appoggiato dalla famiglia dei Pierleoni, con il nome di Anacleto II;

Bernardo appoggiò attivamente il primo che, nella storia della Chiesa, per

quanto eletto da un minor numero di cardinali, sarà riconosciuto come

autentico papa, grazie soprattutto all'appoggio dei maggiori regni europei.

Numerosi furono i suoi interventi in questioni che riguardavano i comportamenti di ecclesiastici: accusò di scorrettezza Simone, vescovo di Noyon e di simonia Enrico, vescovo di Verdun; nel 1138 favorì l'elezione a vescovo di Langres del proprio cugino Goffredo della Roche-Vanneau, malgrado l'opposizione di Pietro il Venerabile e, nel 1141, ad arcivescovo di Bourges di Pietro della Châtre, mentre l'anno dopo ottenne la sostituzione di Guglielmo di Fitz-Herbert, vescovo di York, con l'amico cistercense Enrico Murdac, abate di Fountaine.

I Templari

Nel 1119 alcuni cavalieri, sotto la guida di Ugo di Payns, feudatario della Champagne e parente di Bernardo, fondarono un nuovo ordine monastico-militare, l'Ordine dei Cavalieri del Tempio, con sede in Gerusalemme, nella spianata ove sorgeva il Tempio ebraico; lo scopo dell'Ordine, posto sotto l'autorità del patriarca di Gerusalemme, era di vigilare sulle strade percorse dai pellegrini cristiani. L'Ordine ottenne nel concilio di Troyes del 1128 l'approvazione di papa Onorio II e sembra che la sua regola sia stata ispirata da Bernardo, il quale scrisse, verso il 1135, l'Elogio della nuova cavalleria (De laude novae militiae ad Milites Templi).

L'interesse di Bernardo per le vicende politiche del suo tempo si manifestò anche in occasione dei conflitti che opposero il conte della Champagne, Tibaldo II, da lui sostenuto, al re Luigi VII di Francia e in occasione della repressione, nel 1140, del neonato Comune di Reims, operata dal suo pupillo cistercense, il vescovo Sansone di Mauvoisin.

Il conflitto con Abelardo

Grande fu la risonanza del conflitto che oppose Bernardo al filosofo Pietro Abelardo. Nel 1140 Guglielmo di Saint-Thierry, cistercense del convento di Signy, scriveva al vescovo di Chartres, Goffredo di Lèves e a Bernardo, denunciando che due opere di Abelardo, il Liber sententiarum e la Theologia scholarium, contenevano, a suo giudizio, affermazioni teologicamente erronee, elencandole in un proprio scritto, la Discussione contro Pietro Abelardo.

Bernardo, senza preoccuparsi di leggere i testi (ma è vero?), scrisse a papa Innocenzo II la Lettera 190, sostenendo che Abelardo concepiva la fede una semplice opinione; davanti agli studenti parigini pronunciò il sermone de La conversione, attaccando Abelardo e invitandoli ad abbandonare le sue lezioni.

Abelardo reagì chiedendo all'arcivescovo di Sens di organizzare un pubblico confronto con Bernardo, da tenersi il 3 giugno 1140, ma questi, temendo l'abilità dialettica del suo controversista, il giorno prima presentò 19 affermazioni chiaramente eretiche, attribuendole ad Abelardo, chiamando i vescovi presenti a condannarle e invitando il giorno dopo lo stesso Abelardo a pronunciarsi in proposito. Al rifiuto di Abelardo, che abbandonò il concilio, seguì la condanna dei vescovi, ribadita il 16 luglio successivo dal papa.

La lotta contro gli eretici

Nel 1144 il monaco Evervino di Steinfeld lo informò di un'eresia, di tipo pauperistico, diffusa in quel di Colonia, alla quale rispose con i Sermoni 63, 64, 65 e 66; l'anno successivo accolse l'invito del cardinale di Ostia, Alberico, a combattere un'eresia diffusa nella regione di Tolosa dal monaco Enrico di Losanna, seguace di Pietro di Bruys, critico nei confronti delle gerarchie ecclesiali e propositore di una vita improntata alla povertà e alla penitenza; in questa occasione Bernardo ritenne necessario recarsi, insieme con il suo segretario Goffredo d'Auxerre, a Tolosa. Ottenuta, dopo molti contrasti, una professione di fede, tornò a Chiaravalle e indirizzò una lettera agli abitanti di Tolosa - la Lettera 242 - nella quale esprimeva la sua convinzione che quelle dottrine fossero state definitivamente confutate.

Richiesto ancora di pronunciarsi sulle tesi trinitarie del vescovo di Poitiers e maestro di teologia a Parigi, Gilberto Porretano, nel 1148, nuovamente Bernardo tentò di far approvare da vescovi da lui riuniti a parte, una preventiva condanna che il sinodo da tenere il giorno successivo a Reims avrebbe dovuto semplicemente ratificare; questa volta, tuttavia, i vescovi non appoggiarono la sua iniziativa, tanto che Bernardo dovette cercare appoggio da papa Eugenio III. La difesa di Gilberto - che affermò di non aver mai sostenuto le tesi a lui contestate, frutto, a suo dire, di interpretazioni erronee dei suoi studenti - fece cadere ogni accusa.

La seconda crociata

Il 15 febbraio 1145, a Roma, nel convento di san Cesario, sul Palatino, il conclave eleggeva nuovo papa Eugenio III, abate del convento romano dei Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio; il nuovo papa, Bernardo Paganelli, conosceva bene Bernardo, per averlo incontrato nel concilio di Pisa del 1135 e per essersi ordinato cistercense proprio a Chiaravalle nel 1138. Bernardo, felicitandosi per l'elezione, gli ricordava curiosamente che si diceva «che non siete voi a essere papa, ma io e ovunque, chi ha qualche problema si rivolge a me» e che era stato proprio lui, Bernardo, ad «averlo generato per mezzo del Vangelo».

Eugenio III incaricò Bernardo di predicare a favore della nuova crociata che si stava preparando, e che avrebbe dovuto essere composta soprattutto da francesi, ma Bernardo riuscì a coinvolgere anche i tedeschi. La crociata fu un completo fallimento che Bernardo giustificò, nel suo trattato La considerazione, con i peccati dei crociati, che Dio aveva messo alla prova. Questo trattato, finito di comporre nel 1152 si occupava anche dei compiti del papato, e Bernardo lo mandò a papa Eugenio che si dibatteva tra le difficoltà procurategli dall'opposizione dei repubblicani romani, guidati da Arnaldo da Brescia.

Le sue condizioni di salute cominciano a peggiore alla fine del 1152: ha ancora la forza di intraprendere un viaggio fino a Metz, in Lorena, per mettere fine ai disordini che travagliavano quella città. Tornato a Chiaravalle, apprende la notizia della morte di papa Eugenio, avvenuta l'8 luglio 1153 e muore il mese dopo. Rivestito con un abito appartenuto al vescovo Malachia, del quale aveva appena finito di scrivere una biografia, viene sepolto davanti all'altare della sua abbazia.

La restaurazione della natura umana

Riguardo il suo pensiero teologico e filosofico, Bernardo esprime sul piano morale un orientamento ispirato, apparentemente, al pessimismo: « [...] generati dal peccato, noi peccatori generiamo peccatori; nati corrotti, generiamo dei corrotti; nati schiavi, generiamo degli schiavi. » San Bernardo, dunque, combatte alcune tesi del suo tempo, come la teoria secondo la quale i discendenti di Adamo (cioè noi) non abbiano in sé un «peccato originale» sin dalla nascita, ma solo un «malum poenae», un «male di pena». Bernardo dice anche: « L'uomo è impotente di fronte al peccato. »

Ciò, evidentemente non è una giustificazione al peccato stesso, ma una spiegazione della miseria umana che nei nostri peccati si rivela, ma che è originata dal peccato originale che in ciascuno è impresso come un marchio. Dunque, la questione fondamentale è restaurare la natura umana, per riportare l'uomo al suo stato di «figlio di Dio», e dunque «essere eterno» nella beatitudine del Padre. Poiché ognuno porta in sé il peccato originale, però, nessuno può restaurare la propria natura da solo, ma può farlo solamente attraverso la «mediazione» di Cristo, che è «Soter» (cioè «Salvatore»), proprio in quanto per noi è morto, espiando al nostro posto quel peccato originale che nessun altro poteva espiare, essendone sottoposto. Nella sua opera De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae, tuttavia, dice che, per avere la «mediazione» di Cristo, l'uomo deve superare l'«io di carne», deve limitare e poi annullare la superbia e l'amore di sé, attraverso l'umiltà. Contro di sé, dunque, deve porre l'amore di Dio, poiché solo col Suo amore si ottiene anche la Sua vera intelligenza, e solo con esso « [...] l'anima passa dal mondo delle ombre e delle apparenze all'intensa luce meridiana della Grazia e della verità. »

I quattro gradi dell'amore

Nel De diligendo Deo, San Bernardo continua la spiegazione di come si possa raggiungere l'amore di Dio attraverso la via dell'umiltà. La sua dottrina cristiana dell'amore è originale, indipendente dunque da ogni influenza platonica e neoplatonica. Secondo Bernardo esistono quattro gradi sostanziali dell'amore, che presenta come un itinerario, che dal sé esce, cerca Dio, e infine torna al sé, ma solo per Dio. I gradi sono:

1) L'amore di se stessi per sé: « [...] bisogna che il nostro amore cominci dalla carne. Se poi è diretto secondo un giusto ordine, [...] sotto l'ispirazione della Grazia, sarà infine perfezionato dallo spirito. Infatti non viene prima lo spirituale, ma ciò che è animale precede ciò che è spirituale. [...] Perciò prima l'uomo ama sé stesso per sé [...]. Vedendo poi che da solo non può sussistere, comincia a cercare Dio per mezzo della fede, come un essere necessario e Lo ama. »

2) L'amore di Dio per sé: « Nel secondo grado, quindi, ama Dio, ma per sé, non per Lui. Cominciando però a frequentare Dio e ad onorarlo in rapporto alle proprie necessità, viene a conoscerlo a poco a poco con la lettura, con la riflessione, con la preghiera, con l'obbedienza; così gli si avvicina quasi insensibilmente attraverso una certa familiarità e gusta pura quanto sia soave. »

3) L'amore di Dio per Dio: « Dopo aver assaporato questa soavità l'anima passa al terzo grado, amando Dio non per sé, ma per Lui. In questo grado ci si ferma a lungo, anzi, non so se in questa vita sia possibile raggiungere il quarto grado. »

4) L'amore di sé per Dio: « Quello cioè in cui l'uomo ama sé stesso solo per Dio. [...] Allora, sarà mirabilmente quasi dimentico di sé, quasi abbandonerà sé stesso per tendere tutto a Dio, tanto da essere uno spirito solo con Lui. Io credo che provasse questo il profeta, quando diceva: "-Entrerò nella potenza del Signore e mi ricorderò solo della Tua giustizia-". [...] » (San Bernardo di Chiaravalle, De diligendo Deo, cap. XV)

Nel De diligendo Deo, dunque, San Bernardo presenta l'amore come una forza finalizzata alla più alta e totale fusione in Dio col Suo Spirito, che, oltre a essere sorgente d'ogni amore, ne è anche «foce», in quanto il peccato non sta nell'«odiare», ma nel disperdere l'amore di Dio verso il sé (la carne), non offrendolo così a Dio stesso, Amore d'amore.

Opere

De consideratione libri

quinque ad Eugenium III (La considerazione di cinque libri a Eugenio III)

De diligendo Deo (Dio dev'essere amato)

De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae (I gradi dell'umiltà e della

superbia)

De Gratia et libero arbitrio (La Grazia e il libero arbitrio)

De laude novae militiae ad Milites Templi (La lode della nuova milizia

ai Soldati del Tempio)

De laudibus Virginis Matris (Le lodi della Vergine Madre)

Contemplazione della Passione secondo le ore canoniche

Expositio in Canticum Canticorum (Esposizione nel Cantico dei Cantici)

Meditazione sopra il pianto di Nostra Donna

Sermones (Sermoni)

Sermones de tempore (Sermoni sul tempo)

Sermones super Cantica Canticorum (Sermoni sul Cantico dei Cantici)

Epistola ad Raymundum dominum Castri Ambuosii (Lettera al signore del

Castro Ambuosio Raimondo)

Sermo de miseria humana (Sermone sulla miseria umana)

Tractatus de interiori domo seu de conscientia aedificanda (Trattato

sulla casa interiore o la coscienza che dev'essere edificata)

Varia et brevia documenta pie seu religiose vivendi (Vari e brevi

documenti del vivere piamente o religiosamente)

Visione contemplativa.

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, O.Cist (1090 - August 21, 1153) was a French abbot and the primary builder of the reforming Cistercian monastic order. After the death of his mother, Bernard sought admission into the Cistercian order. Three years later, he was sent to found a new house that Bernard named Claire Vallée, of Clairvaux, on the 25 June 1115 and the names of Bernard and Clairvaux would soon become inseparable. Bernard would preach an immediate faith, in which the intercessor was the Virgin Mary. In the year 1128, Bernard assisted at the Council of Troyes, at which Bernard traced the outlines of the Rule of the Knights Templar who soon became the ideal of Christian nobility.

On the death of Pope Honorius II, which occurred on 14 February 1130, a schism broke out in the Church. King Louis VI convened a national council of the French bishops at Etampes, and Bernard was chosen to judge between the rival popes. Bernard devoted himself with renewed vigour to the composition of the works which would win for him the title of "Doctor of the Church". In 1139, Bernard assisted at the Second Council of the Lateran. Bernard denounced the teachings of Peter Abelard to the Pope who called a council at Sens in 1141 to settle the matter. Bernard soon saw one of his disciples, Bernard of Pisa, and known thereafter as Eugenius III elected Pope. Having previously helped end the schism within the Church, Bernard was now called upon to combat heresy. In June 1145, Bernard traveled in Southern France and his preaching there helped strengthen support against heresy.

Following the Christian defeat at the Siege of Edessa, the Pope commissioned Bernard to preach the Second Crusade. The last years of Bernard's life were saddened by the failure of the crusaders, the entire responsibility for which was thrown upon him. Bernard died at age 63, after 40 years spent in the cloister. He was the first Cistercian monk placed on the calendar of saints and was canonized by Pope Alexander III 18 January 1174. Pope Pius VIII bestowed on him the title of Doctor of the Church.

Early life (1090-1113)

Bernard's parents were Tescelin, lord of Fontaines, and Aleth of Montbard, both belonging to the highest nobility of Burgundy. Bernard was the third of a family of seven children, six of whom were sons. At the age of nine years, Bernard was sent to school at Châtillon-sur-Seine, run by the secular canons of Saint-Vorles. Bernard had a great taste for literature and devoted himself for some time to poetry. His success in his studies won the admiration of his teachers. Bernard wanted to excel in literature in order to take up the study of the Bible. He had a special devotion to the Virgin Mary, and he would later write several works about the Queen of Heaven.

The

Vision of St Bernard

by Fra Bartolomeo c. 1504 - Uffizi - Florence

Bartolomèo di Paolo or Bàccio della Pòrta

(Soffignano, Prato, 1472 - Pian di Mugnone 1517)

Bernard would expand upon Anselm of Canterbury's role in transmuting the sacramentally ritual Christianity of the Early Middle Ages into a new, more personally held faith, with the life of Christ as a model and a new emphasis on the Virgin Mary. In opposition to the rational approach to divine understanding that the scholastics adopted, Bernard would preach an immediate faith, in which the intercessor was the Virgin Mary, “Bernard played the leading role in the development of the Virgin cult, which is one of the most important manifestations of the popular piety of the twelfth century. In early medieval thought, the Virgin Mary had played a minor role and it was only with the rise of emotional Christianity in the eleventh century that she became the prime intercessor for humanity with the deity.”

Bernard was only nineteen years of age when his mother died. During his youth, he did not escape trying temptations and around this time he thought of retiring from the world and living a life of solitude and prayer. In 1098, St Robert of Molesme had founded the monastery of Cîteaux, near Dijon, with the purpose of restoring the Rule of St Benedict in all its rigour. Returning to Molesmes, he left the government of the new abbey to St Alberic, who died in the year 1109. In 1113, St Stephen Harding had just succeeded him as third Abbot of Cîteaux when Bernard and thirty other young noblemen of Burgundy sought admission into the Cistercian order.

Abbot of Clairvaux (1113-28)

The little community of reformed Benedictines at Cîteaux, which would have so profound an influence on Western monasticism grew rapidly. Three years later, Bernard was sent with a band of 12 monks to found a new house at Vallée d'Absinthe, in the Diocese of Langres. This Bernard named Claire Vallée, of Clairvaux, on the 25 June 1115 and the names of Bernard and Clairvaux would soon become inseparable. During the absence of the Bishop of Langres, Bernard was blessed as abbot by William of Champeaux, Bishop of Châlons-sur-Marne. From that moment a strong friendship sprang up between the abbot and the bishop, who was professor of theology at Notre Dame of Paris, and the founder of the cloister of St Victor.

The beginnings of Clairvaux Abbey were trying and painful. The regime was so austere that Bernard became ill, and only the influence of his friend William of Champeaux, and the authority of the General Chapter could make him mitigate the austerities. The monastery, however, made rapid progress. Disciples flocked to it in great numbers and put themselves under the direction of Bernard. His father and all his brothers entered Clairvaux as religious, leaving only Humbeline, his sister, in the world and she, with the consent of her husband, soon took the veil in the Benedictine convent of Jully. Gerard of Clairvaux, Bernard's older brother became the cellarer of Cîteaux. The abbey became too small for the religious who crowded there and it was necessary to send out bands to found new houses. In 1118, the Monastery of the Three Fountains was founded in the Diocese of Châlons. In 1119, that of Fontenay in the Diocese of Autun and in 1121, that of Foigny, near Vervins, in the Diocese of Laon were founded. In addition to these victories, Bernard also has his trials. During an absence from Clairvaux, the Grand Prior of Cluny went to Clairvaux and enticed away the Bernard's cousin, Robert of Châtillon. This was the occasion of the longest, and most emotional of Bernard's letters.

The abbey of Cluny as it would have looked in Bernard's time

In the year 1119, Bernard was present at the first general chapter of the order convoked by Stephen of Cîteaux. Though not yet 30 years old, Bernard was listened to with the greatest attention and respect, especially when he developed his thoughts upon the revival of the primitive spirit of regularity and fervour in all the monastic orders. It was this general chapter that gave definitive form to the constitutions of the order and the regulations of the Charter of Charity which Pope Callixtus II confirmed 23 December 1119. In 1120, Bernard authored his first work De Gradibus Superbiae et Humilitatis and his homilies which he entitles De Laudibus Mariae.

The monks of the abbey of Cluny were unhappy to see Cîteaux take the lead rôle among the religious orders of the Roman Catholic Church. For this reason, the Black Monks attempted to make it appear that the rules of the new order were impracticable. At the solicitation of William of St. Thierry, Bernard defended the order by publishing his Apology which was divided into two parts. In the first part, he proved himself innocent of the charges of Cluny and in the second he gave his reasons for his counterattacks. He protested his profound esteem for the Benedictines of Cluny whom he declared he loved equally as well as the other religious orders.

Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny, answered Benedict and assured him of his great admiration and sincere friendship. In the meantime Cluny established a reform, and Abbot Suger, the minister of Louis VI of France, was converted by the Apology of Bernard. He hastened to terminate his worldly life and restore discipline in his monastery. The zeal of Bernard extended to the bishops, the clergy, and lay people. Bernard's letter to the Archbishop of Sens was seen as a real treatise, De Officiis Episcoporum. About the same time he wrote his work on Grace and Free Will.

Doctor of the Church (1128-46)

In the year 1128, Bernard assisted at the Council of Troyes, which had been convoked by Pope Honorius II, and was presided over by Cardinal Matthew, Bishop of Albano. The purpose of this council was to settle certain disputes of the bishops of Paris, and regulate other matters of the Church of France. The bishops made Bernard secretary of the council, and charged him with drawing up the synodal statutes. After the council, the Bishop of Verdun was deposed. Again unjust reproaches arose against Bernard and he was denounced even in Rome. He was accused of being a monk who meddled with matters that did not concern him.

Cardinal Harmeric, on behalf of the pope, wrote Bernard a sharp letter of remonstrance stating, "It is not fitting that noisy and troublesome frogs should come out of their marshes to trouble the Holy See and the cardinals". Bernard answered the letter by saying that, if he had assisted at the council, it was because he had been dragged to it by force. In his response Bernard wrote, "Now illustrious Harmeric if you so wished, who would have been more capable of freeing me from the necessity of assisting at the council than yourself? Forbid those noisy troublesome frogs to come out of their holes, to leave their marshes . . . Then your friend will no longer be exposed to the accusations of pride and presumption" This letter made a great impression upon the cardinal, and justified its author both in his eyes and before the Holy See. It was at this council that Bernard traced the outlines of the Rule of the Knights Templar who soon became the ideal of Christian nobility. He later praised them in his De Laudibus Novae Militiae.

Schism

Bernard's influence was soon felt in provincial affairs. He defended the rights of the Church against the encroachments of kings and princes, and recalled to their duty Henri Sanglier, Archbishop of Sens and Stephen of Senlis, Bishop of Paris. On the death of Pope Honorius II, which occurred on 14 February 1130, a schism broke out in the Church by the election of two popes, Pope Innocent II and Pope Anacletus II. Innocent II having been banished from Rome by Anacletus took refuge in France. King Louis VI convened a national council of the French bishops at Étampes, and Bernard, summoned there by consent of the bishops, was chosen to judge between the rival popes. He decided in favour of Innocent II. This caused the Pope to be recognized by all the great powers. He then went with him into Italy and reconciled Pisa with Genoa, and Milan with the Pope. The same year Bernard was again at the Council of Reims at the side of Innocent II. He then went to Aquitaine where he succeeded for the time in detaching William X of Aquitaine, Count of Poitiers, from the cause of Anacletus.

In 1132, Bernard accompanied Innocent II into Italy, and at Cluny the Pope abolished the dues which Clairvaux used to pay to that abbey. This action gave rise to a quarrel between the White Monks and the Black Monks which lasted 20 years. In May of that year, the Pope supported by the army of Emperor Lothaire III, entered Rome, but Lothaire, feeling himself too weak to resist the partisans of Anacletus, retired beyond the Alps, and Innocent sought refuge in Pisa in September 1133. Bernard had returned to France in June, and was continuing the work of peacemaking which he had commenced in 1130. Towards the end of 1134, he made a second journey into Aquitaine, where William X had relapsed into schism. Bernard invited William to the Mass which he celebrated in the Church of La Couldre. At the Eucharist, he "admonished the Duke not to despise God as he did His servants". William yielded and the schism ended. Bernard went again to Italy, where Roger II of Sicily was endeavouring to withdraw the Pisans from their allegiance to Innocent. He recalled the city of Milan to obedience to the Pope as they had followed the deposed Anselm V, Archbishop of Milan. For this, he was offered, and he refused, the Archbishopric of Milan. He then returned to Clairvaux. Believing himself at last secure in his cloister, Bernard devoted himself with renewed vigour to the composition of the works which would win for him the title of "Doctor of the Church". He wrote at this time his sermons on the Song of Songs. In 1137 he was again forced to leave his solitude by order of the Pope to put an end to the quarrel between Lothaire and Roger of Sicily. At the conference held at Palermo, Bernard succeeded in convincing Roger of the rights of Innocent II. He also silenced the final supporters who sustained the schism. Anacletus died of "grief and disappointment" in 1138, and with him the schism ended.

Contest with Abelard

In 1139, Bernard assisted at the Second Council of the Lateran, in which the surviving adherents of the schism were definitively condemned. About the same time, Bernard was visited at Clairvaux by St Malachi, Primate of All Ireland, and a very close friendship was formed between them. Malachi wanted to become a Cistercian, but the Pope would not give his permission. Malachi would die at Clairvaux in 1148.

Towards the close of the 11th century, the schools of philosophy and theology were dominated by a spirit of independence. This led for a time to the exaltation of human reason and rationalism. This movement found an ardent and powerful adherent in Peter Abelard. Abelard's treatise on the Trinity had been condemned in 1121, and he himself had thrown his book into the fire. In 1139, Abelard advocated new positions at odds with those of Rome. Bernard, informed of this by William of St-Thierry, wrote to Abelard who answered in an insulting manner. Bernard then denounced him to the Pope who called a council at Sens in 1141 to settle the matter. There, Abelard asked for a public debate with Bernard. Bernard's delivered Rome's case with such clearness and force of logic that Abelard made no reply. He was obliged, after being condemned, to retire. The Pope confirmed the judgment of the council, Abelard submitted without resistance, and retired to Cluny to live under Peter the Venerable, where he died two years later.

Cistercian Order and heresy

Bernard had occupied himself in sending bands of monks from his too-crowded monastery into Germany, Sweden, England, Ireland, Portugal, Switzerland, and Italy. Some of these, at the command of Innocent II, took possession of Three Fountains Abbey, from which Pope Eugenius III would be chosen in 1145. Innocent II died in 1143. His two successors, Pope Celestine II and Pope Lucius II, reigned only a short time, and then Bernard saw one of his disciples, Bernard of Pisa, and known thereafter as Eugenius III, raised to the Chair of Saint Peter. Bernard sent him, at the Pope's own request, various instructions which compose the Book of Considerations, the predominating idea of which is that the reformation of the Church ought to commence with the sanctity of the Pope. Temporal matters are merely accessories, the principals according to Bernard's work were piety, and meditation which was to precede action.

Having previously helped end the schism within the Church, Bernard was now called upon to combat heresy. Henry of Lausanne, a former Cluniac monk, had adopted the teachings of the Petrobrusians, followers of Peter of Bruys and spread them in a modified form after Peter's death. Henry of Lausanne's followers became known as Henricians. In June 1145, at the invitation of Cardinal Alberic of Ostia, Bernard traveled in Southern France. His preaching, aided by his ascetic looks and simple attire, helped doom the new sects. Both the Henrician and the Petrobrusian faiths began to die out by the end of that year. Soon afterwards, Henry of Lausanne was arrested, brought before the Bishop of Toulouse, and probably imprisoned for life. In a letter to the people of Toulouse, undoubtedly written at the end of 1146, Bernard calls upon them to extirpate the last remnants of the heresy. He also preached against the Cathars.

Second Crusade (1146-49)

News came at this time from the Holy Land that alarmed Christendom. Christians had been defeated at the Siege of Edessa and most of the county had fallen into the hands of the Turks. The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the other Crusader states were threatened with similar disaster. Deputations of the bishops of Armenia solicited aid from the Pope, and the King of France also sent ambassadors. The Pope commissioned Bernard to preach a Second Crusade and granted the same indulgences for it which Pope Urban II had accorded to the First Crusade.

There was at first virtually no popular enthusiasm for the crusade as there had been in 1095. Bernard found it expedient to dwell upon the taking of the cross as a potent means of gaining absolution for sin and attaining grace. On 31 March, with King Louis present, he preached to an enormous crowd in a field at Vézelay. When Bernard was finished the croud enlisted en masse; they supposedly ran out of cloth to make crosses. Bernard is said to have given his own outer garments to be cut up to make more. Unlike the First Crusade, the new venture attracted Royalty, such as Eleanor of Aquitaine, then Queen of France; Thierry of Alsace, Count of Flanders; Henry, the future Count of Champagne; Louis’ brother Robert I of Dreux; Alphonse I of Toulouse; William II of Nevers; William de Warenne, 3rd Earl of Surrey; Hugh VII of Lusignan; and numerous other nobles and bishops. But an even greater show of support came from the common people. Bernard wrote to the Pope a few days afterwards, "Cities and castles are now empty. There is not left one man to seven women, and everywhere there are widows to still living husbands."

Bernard then passed into Germany, and the reported miracles which multiplied almost at his every step undoubtedly contributed to the success of his mission. Conrad III of Germany and his nephew Frederick Barbarossa, received the cross from the hand of Bernard. Pope Eugenius came in person to France to encourage the enterprise. As in the First Crusade, the preaching inadvertently led to attacks on Jews; a fanatical French monk named Rudolphe was apparently inspiring massacres of Jews in the Rhineland, Cologne, Mainz, Worms, and Speyer, with Rudolphe claiming Jews were not contributing financially to the rescue of the Holy Land. The Archbishop of Cologne and the Archbishop of Mainz were vehemently opposed to these attacks and asked Bernard to denounce them. This he did, but when the campaign continued, Bernard traveled from Flanders to Germany to deal with the problems in person. He then found Rudolphe in Mainz and was able to silence him, returning him to his monastery.

The last years of Bernard's life were saddened by the failure of the Second Crusade he had preached, the entire responsibility for which was thrown upon him. He had accredited the enterprise by his reported miracles, but he had not guaranteed its success against the misconduct of those who participated in it. Lack of discipline and the over-confidence of the German troops, the intrigues of the Prince of Antioch and his niece Queen Eleanor, and finally the blunders of the Christian nobles, who failed at the siege of Damascus, appear to have been the cause of disaster. Bernard considered it his duty to send an apology to the Pope and it is inserted in the second part of his Book of Considerations. There he explains how the sins of the crusaders were the cause of their misfortune and failures. When his attempt to call a new crusade failed, he tried to disassociate himself from the fiasco of the Second Crusade altogether.

Final years (1149-53)

The death of his contemporaries served as a warning to Bernard of his own approaching end. The first to die was Suger in 1152, of whom Bernard wrote to Eugenius III, "If there is any precious vase adorning the palace of the King of Kings it is the soul of the venerable Suger". Conrad III and his son Henry died the same year. From the beginning of the year 1153, Bernard felt his death approaching. The passing of Pope Eugenius had struck the fatal blow by taking from him one whom he considered his greatest friend and consoler. Bernard died at age 63 on 20 August 1153, after 40 years spent in the cloister.

Theology

At the 800th anniversary of his death, Pope Pius XII issued an encyclical on Bernard, Doctor Mellifluus in which he labeled him The Last of the Fathers. Bernard did not reject human philosophy which is genuine philosophy, which leads to God; he differentiates different kind of knowledge, the highest being theological. Three central elements of Bernard’s mariology are: how he explained the virginity of Mary, the “Star of the Sea”, how the faithful should pray on the Virgin Mary, and how he relied on the Virgin Mary as Mediatrix.

Legacy

Bernard's theology and mariology continue to be of major importance, particularly within the Cistercian and Trappist orders. Bernard led to the foundation of 163 monasteries in different parts of Europe. At his death, they numbered 343. His influence led Pope Alexander III to launch reforms that would lead to the establishment of canon law. He was the first Cistercian monk placed on the calendar of saints and was canonized by Pope Alexander III 18 January 1174. Pope Pius VIII bestowed on him the title of Doctor of the Church. He became remembered as the Mellifluous Doctor, the Honey-Sweet Doctor, for his eloquence. The Cistercians honour him as only the founders of orders are honoured, because of the widespread activity which he gave to the order. The works of Bernard are as follows:

De

Gradibus Superbiae, his first treatise.

Homilies on the Gospel "Missus est" written in 1120.

Apology to William of St. Thierry against the claims of the monks of

Cluny.

On the Conversion of Clerics, a book addressed to the young

ecclesiastics of Paris written in 1122.

De Laudibus Novae Militiae, addressed to Hugues de Payens, first Grand

Master and Prior of Jerusalem (1129). This is a eulogy of the military order

instituted in 1118, and an exhortation to the knights to conduct themselves

with courage in their several stations.

De amore Dei wherein Bernard argues that the manner of loving God is to

love without measure and gives the different degree of this love.

Book of Precepts and Dispensations (1131), which contains answers to

questions upon certain points of the Rule of St Benedict from which the abbot

can, or cannot, dispense.

De Gratiâ et Libero Arbitrio in which the Roman Catholic dogma of

grace and free will was defended according to the principles of St Augustine.

Book of Considerations, addressed to Pope Eugenius III.

De Officiis Episcoporum, addressed to Henry, Archbishop of Sens.

His sermons are also numerous:

On Psalm 90, "Qui habitat", written about 1125.

On the Song of Songs.

There are also 86 Sermons for the Whole Year.

530 letters survive.

Many letters, treatises, and other works, falsely attributed to him survive, such as the l'Echelle du Cloître, les Méditations, and l'Edification de la Maison intérieure.

Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy places him as the last guide for Dante, as he travels through the Empyrean. As the final guide, he represents the Contemplative Soul who is able to lead Dante to his viewing of God.

Stained

glass representing Bernard.

Upper Rhine, ca. 1450.