Lessico

Andrea Cesalpino

Botanico,

medico e filosofo italiano (Arezzo 1519 - Roma 1603). Professore dapprima

all'Università di Pisa, fu poi a Roma, medico di Clemente VIII e professore

al Collegio della Sapienza. Può considerarsi, con l'Aldrovandi e il Mattioli![]() ,

l'iniziatore della botanica sistematica. Stabilì un sistema di

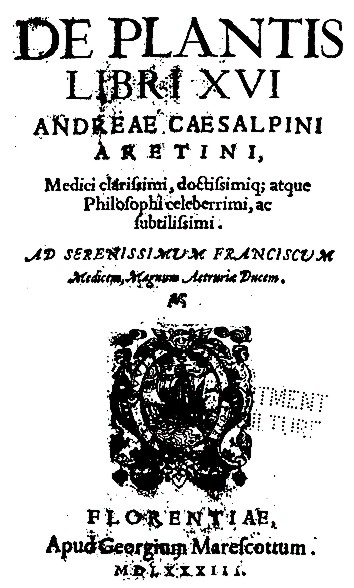

classificazione e di nomenclatura dei vegetali, esposto nel trattato De

plantis libri XVI (1583), in cui descrisse 840 specie raggruppate in 15

classi.

,

l'iniziatore della botanica sistematica. Stabilì un sistema di

classificazione e di nomenclatura dei vegetali, esposto nel trattato De

plantis libri XVI (1583), in cui descrisse 840 specie raggruppate in 15

classi.

Il suo

sistema si basava soprattutto sull'organizzazione del frutto, mentre il fiore

è considerato solo un organo protettivo del seme. Altrettanto importanti i

suoi studi medici riuniti nei Quaestionum peripateticarum libri V

(1571), in cui segue una filosofia della natura di ispirazione aristotelica,

riducendo però la dualità di forma e materia a un unico principio supremo,

per cui si è accostata la sua concezione al pensiero di Spinoza. Ritenne che

negli animali vi fosse un unico centro della vita localizzato nel cuore e, a

sostegno di questa tesi, tentò di dimostrare, confutando le teorie di Galeno![]() , che le

vene originano nel cuore, punto nodale del movimento del sangue, e non nel

fegato. Seguendo gli studi di Realdo Colombo, descrisse con esattezza il

circolo polmonare e riconobbe anche l'esistenza di connessioni periferiche fra

le vene e le arterie. Si è perciò sostenuto, non senza vivaci polemiche, la

sua priorità su William Harvey

, che le

vene originano nel cuore, punto nodale del movimento del sangue, e non nel

fegato. Seguendo gli studi di Realdo Colombo, descrisse con esattezza il

circolo polmonare e riconobbe anche l'esistenza di connessioni periferiche fra

le vene e le arterie. Si è perciò sostenuto, non senza vivaci polemiche, la

sua priorità su William Harvey![]() (1578-1657) nella scoperta della circolazione del sangue.

(1578-1657) nella scoperta della circolazione del sangue.

Il monaco

francescano e illustre botanico Charles Plumier![]() (Marseille

20 avril 1646 - Santa Maria près de Cadixgave le 20 novembre 1704) per

onorare Andrea Cesalpino diede il nome di Caesalpina a un genere di

piante della famiglia Leguminosae o Fabaceae o Papilionaceae

e Linneo

(Marseille

20 avril 1646 - Santa Maria près de Cadixgave le 20 novembre 1704) per

onorare Andrea Cesalpino diede il nome di Caesalpina a un genere di

piante della famiglia Leguminosae o Fabaceae o Papilionaceae

e Linneo![]() lo inserì

nella sua classificazione come Caesalpinia.

lo inserì

nella sua classificazione come Caesalpinia.

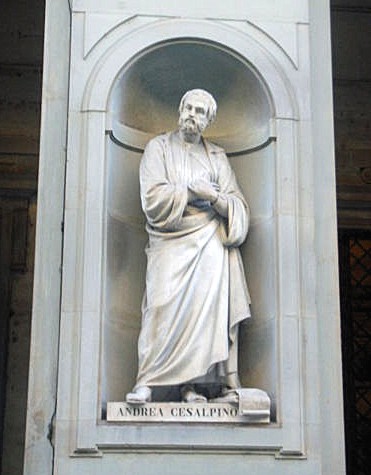

Andrea Cesalpino

Piazzale degli Uffizi - Firenze

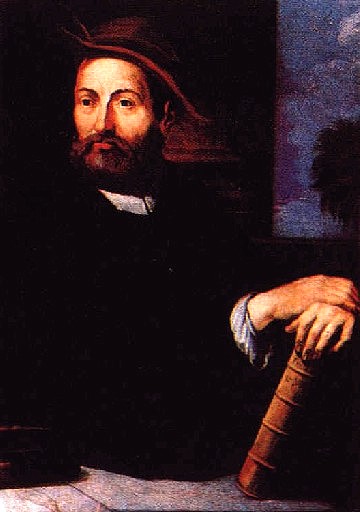

Andrea Cesalpino o, impropriamente, Andrea Cisalpino (Arezzo, 6 giugno 1519 – Roma, 23 febbraio 1603) è stato un botanico, medico e anatomista italiano. Nato ad Arezzo nel 1519, Cesalpino svolse i sui studi all'Università di Pisa, dove si laureò del 1551. A Pisa diresse l'Orto Botanico e insegnò Medicina.

Fece parte della scuola anatomica che fiorì a Padova nella seconda metà del 1500. Compì le prime vere grandi scoperte sulla circolazione del sangue. Suo merito fondamentale è di aver definito - con la testimonianza del reperto anatomico - che il cuore (e non il fegato) è il centro del movimento del sangue e il punto di partenza delle arterie e delle vene.

Nel 1592 papa Clemente VIII lo chiamò a Roma. Anche in questa città insegnò medicina ed ebbe l'incarico di medico personale del papa. L'anno dopo diede la prova della "circolazione" dimostrando che le vene legate in qualsiasi parte del corpo si tumefanno "sotto il laccio, cioè dalla periferia al centro", e che - quando aperte, come nel salasso - lasciano fuoriuscire dapprima sangue scuro venoso e poi sangue rosso arterioso. Era la prova concreta che esiste una corrente centripeta opposta rispetto a quello che, tramite l'aorta e i suoi rami, porta il sangue dal cuore alla periferia. Nel sistema vasale esistevano quindi due correnti opposte. Nell'ambito della botanica, invece, studiò e sviluppò nuovi sistemi di classificazione delle piante.

Andrea Cesalpino (Latinized as Andreas Caesalpinus) (June 6, 1519 – February 23, 1603) was an Italian physician, philosopher and botanist. In his works he classified plants according to their fruits and seeds, rather than alphabetically or by medicinal properties. In 1555, he succeeded Luca Ghini as director of the botanic garden in Pisa. The botanist Pietro Castelli was one of his students. Cesalpino also did limited work in the field of physiology. He theorized a circulation of the blood. However, he envisioned a "chemical circulation" consisting of repeated evaporation and condensation of blood, rather than the concept of "physical circulation" popularized by the writings of William Harvey (1578–1657).

Cesalpino was born at Arezzo, Tuscany. For his studies at the University of Pisa his instructor in medicine was Realdo Colombo (Cremona ca. 1520 -? 1559), and in botany the celebrated Luca Ghini (Croara d'Imola ca. 1490 - Bologna 1556).. After completing his course he taught philosophy, medicine, and botany for many years at the same university, besides making botanical explorations in various parts of Italy.

At this time the first botanical gardens in Europe were laid out; the earliest at Padua, in 1546; the next at Pisa in 1547 by Ghini, who was its first director. Ghini was succeeded by Cesalpino, who had charge of the Pisan garden 1554-1558. When far advanced in years Cesalpino accepted a call to Rome as professor of medicine at University of Rome La Sapienza and physician to Pope Clement VIII. It is not positively certain whether he also become the chief superintendent of the Roman botanical garden which had been laid out about 1566 by one of his most celebrated pupils, Michele Mercati.

All of Cesalpino's writings show the man of genius and the profound thinker. His style, it is true, is often heavy, yet in spite of the scholastic form in which his works are cast, passages of great beauty often occur. Modern botanists and physiologists who are not acquainted with the writings of Aristotle find Cesalpino's books obscure; their failure to comprehend them has frequently misled them in their judgment of his achievement.

No comprehensive summing up of the results of Cesalpino's investigations, founded on a critical study of all his works has appeared, neither has there been a complete edition of his writings. Seven of these are positively known, and most of the seven have been printed several times, although none have appeared since the 17th century. In the following list the date of publication given is that of the first edition.

His most important philosophical work is Quaestionum peripateticarum libri V (Florence, 1569). Cesalpino proves himself in this to be one of the most eminent and original students of Aristotle in the 16th century. His writings, however, show traces of the influence of Averroes, hence he is an Averroistic Aristotelean; apparently he was also inclined to pantheism, consequently he was included, later, in the Spinozists before Spinoza. A Protestant opponent of Aristotelean views, Nicolaus Taurellus, who is called "the first German philosopher," wrote several times against Cesalpino. The work of Taurellus entitled Alpes caesae, etc. (Frankfurt, 1597), is entirely devoted to combating the opinions of Cesalpino, as the play on the name Caesalpinus shows. Nearly one hundred years later Cesalpino's views were again attacked, this time by an Englishman, Samuel Parker, in a work entitled Disputationes de Deo et providentia divina (London, 1678).

Cesalpino repeatedly asserted the steadfastness of his Catholic principles and his readiness to acknowledge the falsity of any philosophical opinions expounded by him as Aristotelean doctrine, which should be contrary to revelation. In Italy he was in high favour both with the secular and spiritual rulers.

Cesalpino's physiological investigations concerning the circulation of the blood are well known, but even up to the present time they have been as often overestimated as undervalued. An examination of the various passages in his writings which bear upon the question shows that although it must be said that Celsalpino had penetrated further into the secret of circulation of the blood than any other physiologist before William Harvey, still he had not attained to a thorough knowledge, founded on anatomical research, of the entire course of the blood. Besides the work Quæstionum peripateticarum already mentioned, reference should be made to Quaestionum medicarum libri duo (Venice, 1593).

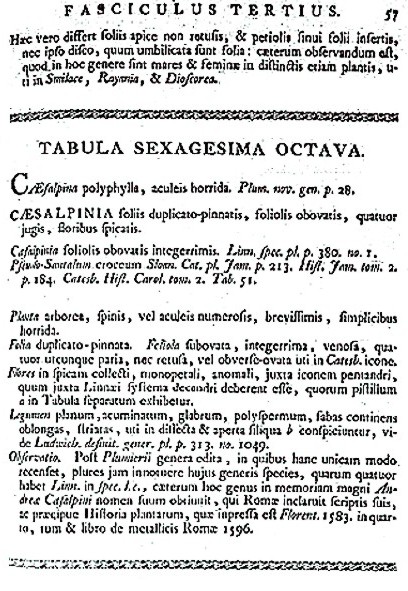

His most important publication was De plantis libri XVI (Florence, 1583). The date of its publication, 1583, is one of the most important in the history of botany before Carolus Linnaeus. The work is dedicated to the Grand Duke Francesco I de' Medici. Unlike the "herbals" of that period, it contains no illustrations. The first section, including thirty pages of the work, is the part of most importance for botany in general. From the beginning of the 17th century up to the present day botanists have agreed in the opinion that Cesalpino in this work, in which he took Aristotle for his guide, laid the foundation of the morphology and physiology of plants and produced the first scientific classification of flowering plants. Three things, above all, give the book the stamp of individuality: the large number of original, acute observations, especially on flowers, fruits, and seeds, made, moreover, before the discovery of the microscope, the selection of the organs of fructification for the foundation of his botanical system; finally, the ingenious and at the same time strictly philosophical handling of the rich material gathered by observation. Cesalpino issued a publication supplementary to this work, entitled Appendix ad libros de plantis et quaestiones peripateticas (Rome, 1603).

Cesalpino is also famous in the history of botany as one of the first botanists to make an herbarium; one of the oldest herbaria still in existence is that which he arranged about 1550-60 for Bishop Alfonso Tornabono. After many changes of fortune the herbarium is now in the Museo di Storia Naturale di Firenze at Florence. It consists of 260 folio pages arranged in three volumes bound in red leather, and contains 768 species of plants. A work of some value for chemistry, mineralogy, and geology was issued by him under the title De metallicis libri tres (Rome, 1596). Some of its matter recalls the discoveries made at the end of the eighteenth century, as those of Antoine Lavoisier and René Just Haüy, it also shows a correct understanding of fossils.

Charles Plumier

The Franciscan monk Charles Plumier![]() (Marseille 20 avril 1646 - Santa Maria près de

Cadixgave le 20 novembre 1704) gave the name of Caesalpina to a plant

genus and Linnaeus retained it as Caesalpinia in his system. At the

present day this genus includes approximately 150 species, which contains a

large number of useful plants. Linnaeus in his writings often quotes his great

predecessor in the science of botany and praises Cesalpino in the following

lines:

(Marseille 20 avril 1646 - Santa Maria près de

Cadixgave le 20 novembre 1704) gave the name of Caesalpina to a plant

genus and Linnaeus retained it as Caesalpinia in his system. At the

present day this genus includes approximately 150 species, which contains a

large number of useful plants. Linnaeus in his writings often quotes his great

predecessor in the science of botany and praises Cesalpino in the following

lines:

Quisquis hic exstiterit primos concedat honores

Casalpine Tibi primaque certa dabit.

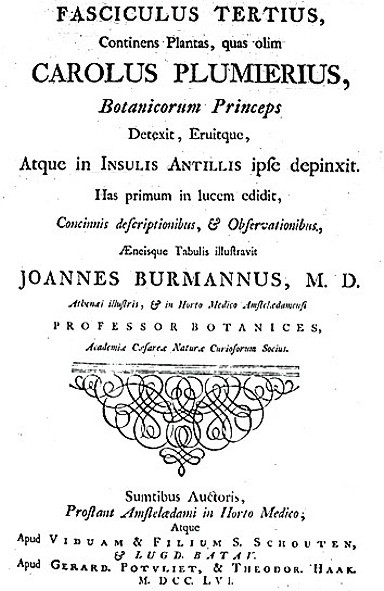

Dictionnaire historique

de la médecine ancienne et moderne

par Nicolas François Joseph Eloy

Mons – 1778

André Césalpin

Andrea Cesalpino (Andreas Caesalpinus en latin et André Césalpin en français), né le 6 juin 1519 à Arezzo en Toscane et mort le 23 février 1603 à Rome, était un philosophe, médecin, naturaliste et botaniste italien.

Andrea Cesalpino étudie à l'université de Pise. Son professeur de médecine est Realdo Colombo († 1559) et celui de botanique Luca Ghini. Après ses études, il enseigne longtemps, à la même université, la philosophie, la médecine et la botanique. Il fait de nombreuses herborisations en Italie. Cesalpino succède à Ghini à la tête du jardin botanique de Pise en 1554, fonction qu'il occupera jusqu'en 1558. Il est appelé à Rome pour enseigner la médecine et être le médecin personnel du pape Clément VIII qui le nomma professeur de médecine au collège de la Sapience.

Les écrits de Cesalpino ne sont pas toujours faciles à comprendre. Comme philosophe, il se fait remarquer par sa connaissance profonde des écrits d'Aristote. Ses écrits portent l'influence d'Averroès et le montre enclin au panthéisme. Son œuvre philosophique la plus importante est Quaestionum peripateticarum libri V (parue à Florence en 1569) où Cesalpino étudie la pensée d'Aristote.

Il embrasse la secte des Averroïstes, représentant Dieu non comme la cause, mais comme le fond et la substance de toutes choses, ce qui le fait accuser de panthéisme et même d'athéisme. Cependant, la Catholic Encyclopedia indique qu'il était resté catholique toute sa vie.

En médecine, il soupçonna un des premiers, à la suite de son maître Realdo Colombo, la circulation du sang. Comme naturaliste, il reconnut le sexe dans les fleurs et inventa la première méthode de botanique: il fondait sa classification sur la forme de la fleur, du fruit, et sur le nombre des graines. Son œuvre la plus importante est certainement De plantis libri XVI (parue à Florence en 1583). Ce livre est proche des herbiers antérieurs et présente une théorie botanique, proche de celle dérivée de la pensée aristotélicienne. Il décrit environ 1500 espèces qu'il tente de classer suivant un système permettant une détermination ultérieure facile. Il suit d'ailleurs les préceptes de Théophraste. Il fait une large place à ses propres observations et expériences. Il rejette les systèmes de classification basés sur des critères artificiels (comme le goût, les utilisations médicinales ou l'ordre alphabétique) et tente de trouver un système naturel. Contrairement aux autres herbiers, il ne contient aucune illustration, car Cesalpino estime que seul le texte permet de décrire précisément toutes les caractéristiques contrairement aux représentations graphiques.

Cesalpino aborde de façon très novatrice l'étude des végétaux et plante les fondements modernes de la morphologie et de la physiologie végétales. Il évoque ainsi la nutrition des plantes et se basant sur les euphorbes qui laissent couler un jus laiteux quand on coupe une feuille, fait une analogie avec la circulation du sang chez les animaux.

Comme Conrad Gessner, il considère que l'élément de base pour la classification est l'espèce basée sur le principe de la reproduction avec ses semblables et accorde beaucoup d'importance aux organes reproducteurs. Il étudie également la chimie, la minéralogie et la géologie. Dans De metallicis libri tres (publié à Rome en 1596), il montre une bonne compréhension des fossiles.

Les doctrines philosophiques de Cesalpino furent combattues par Samuel Parker, archevêque de Cantorbéry, et par Nicolas Taurel, médecin de Montbéliard, qui le dénoncèrent à l'Inquisition.

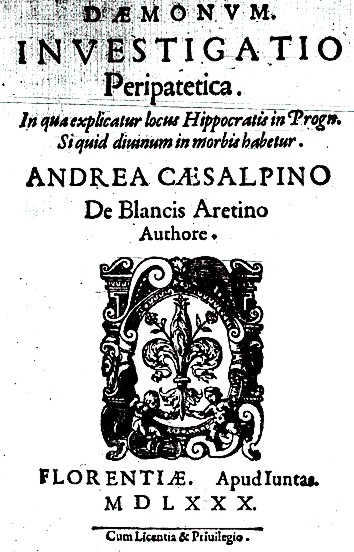

Ses principaux ouvrages sont: Quaestiones peripateticae, Florence, 1569; Daemonum investigatio, 1580: il y combat la magie et la sorcellerie; Ars medica, Rome, 1601; De plantis, Florence, 1583, le plus important de tous; De metallis, 1596, ouvrage qui a moins de valeur.

Charles

Plumier![]() lui dédie

un genre de plante, les Caesalpinia de la famille des Leguminosae

ou Papilionaceae ou Fabaceae.

lui dédie

un genre de plante, les Caesalpinia de la famille des Leguminosae

ou Papilionaceae ou Fabaceae.

Il monaco

francescano e illustre botanico Charles Plumier![]() (Marseille

20 aprile 1646 - Santa Maria près de Cadixgave 20 novembre 1704) per onorare

Andrea Cesalpino diede il nome di Caesalpina a un genere di piante

della famiglia Leguminosae o Fabaceae o Papilionaceae e

Linneo

(Marseille

20 aprile 1646 - Santa Maria près de Cadixgave 20 novembre 1704) per onorare

Andrea Cesalpino diede il nome di Caesalpina a un genere di piante

della famiglia Leguminosae o Fabaceae o Papilionaceae e

Linneo![]() lo inserì

nella sua classificazione come Caesalpinia.

lo inserì

nella sua classificazione come Caesalpinia.

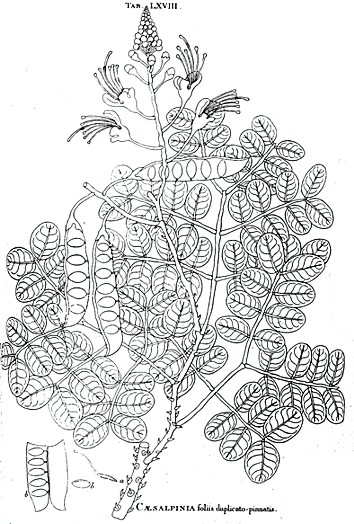

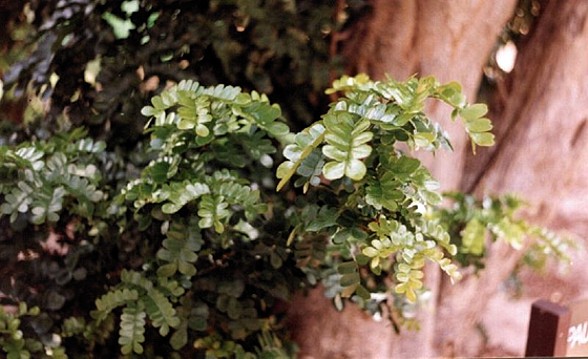

Caesalpinia costituisce un genere di piante della famiglia Leguminosae con un centinaio di specie arboree o arbustive. Alcune forniscono legnami pesanti, come Caesalpinia sappan dell'Asia tropicale (legno sappan) e Caesalpinia crista (legno di Santa Maria); altre, come Caesalpinia echinata, danno legno tintorio o sono utilizzate per il tannino, come la Caesalpinia coriaria. Caesalpinia sepiaria, oriunda dell'Asia, è coltivata per ornamento nell'Europa meridionale.

Caesalpinia

Caesalpinia is the name of a genus of controversial size (different publications including between 70 and 165 species, mostly depending on inclusion or exclusion of various genera such as Hoffmanseggia), consisting of tropical and subtropical woody plants. It is named after the botanist Andrea Cesalpino.

The name Caesalpiniaceae at family level, or Caesalpinioideae at the level of subfamily, is based on this generic name. Some species are grown for their ornamental flowers, and Caesalpinia echinata, Brazilwood, is the source of a historically important dye called brazilin and of the wood for violin bows.

Selected species

Caesalpinia

bonduc (Nickernut)

Caesalpinia cassioides

Caesalpinia conzattii

Caesalpinia coriaria (Divi-divi)

Caesalpinia decapetala (Mysore Thorn)

Caesalpinia echinata (Brazilwood)

Caesalpinia ferrea

Caesalpinia gilliesii (Bird of Paradise)

Caesalpinia mexicana

Caesalpinia platyloba

Caesalpinia pulcherrima

Caesalpinia punctata (Quebrahacha, Kibrahacha in Aruba)

Caesalpinia reticulata

Caesalpinia sappan (Sappanwood)

Caesalpinia spinosa

Caesalpinia vesicaria

Caesalpinia violacea

Caesalpinia virgata

Questa specie ha dato il nome al Brasile. Il termine brasil riconosce questa sequenza etimologica: brasa à braise à brésil. Brasa è parola germanica che indica carbone ardente, braise è la grafia francese che poi è stata adattata all'aggettivo brésil, anch'esso francese. La lingua lusitana, che ha molto in comune col francese, ha trasformato l'aggettivo secondo il suono germanico, cioè in brasil. Tutto ciò in quanto la Caesalpinia echinata fornisce una tinta marrone rossiccio, quasi color brace

Ecco le caratteristiche della Caesalpinia echinata: corteccia grigia, foglie perenni, fiori giallo intenso, non molto dissimile dalla quercia, però fornitrice di un’ottima tinta marrone rossiccio, quasi color brace, detta quindi in portoghese pau brasil, cioè palo rosso brace. Il legno appena tagliato è color crema, ma subito dopo diventa rosso scuro, quasi ocra.

Un tempo il rosso era di moda, specie presso la Corte Francese. Anche se il pau brasil non era un colorante stabile, servì ottimamente a giustificare le traversate oceaniche per un costante approvvigionamento. Prima della scoperta dei coloranti anilinici, i procedimenti di estrazione della brasileina - composto di tipo flavonico di colore rosso - si basavano su alberi appartenenti al genere Cæsalpinia. Questo legno è oggi richiesto per lavori di fine falegnameria e per strumenti musicali.

Pau brasil

Pau brasil è il nome popolare della specie Caesalpinia echinata Lam., un albero della famiglia delle Fabaceae nativo della Mata Atlântica, la foresta vergine che ricopriva completamente le regioni litoranee del Brasile. Il nome popolare "pau brasil" significa letteralmente in portoghese "albero brasil". La parola brasil potrebbe derivare dal colore rosso brace (brasa in portoghese) della resina contenuta nel legno. Ma esistono molte altre etimologie alternative della parola brasil, cosicché non è possibile essere conclusivi al riguardo dell'origine del nome pau-brasil. Il nome Brasile deriva comunque da questa pianta.

Nella lingua tupi il "pau brasil" è chiamato Ibira pitanga, o legno rosso. L'albero del "pau brasil" raggiunge 10-15 metri di altezza. Possiede un tronco eretto, grigio scuro, ricoperto di spine, specialmente nei rami più giovani (echinata significa "con spine"). Le foglie sono composte paripennate, dal colore verde brillante.

I fiori nascono in grappoli eretti nei pressi dell'apice dei rami. Posseggono quattro petali gialli e uno minore rosso e sono soavemente profumati; nel centro si trovano dieci stami e un pistillo, con ovario allungato. I frutti sono bacche di color marrone, coperte da lunghe e affilate spine. Le bacche contengono da 1 a 5 semi a forma di disco.

La prima attività economica dei coloni portoghesi nella appena scoperta Terra de Santa Cruz, l'antico nome del Brasile (secolo XVI), fu proprio il taglio del "pau brasil" per ottenere legno pregiato e resina. La resina rossa commercialmente nota come brasileina era usata come colorante dall'industria tessile europea e conferiva ai tessuti un colore di qualità superiore. Questo fatto, unito allo sfruttamento industriale del legno rosso, generò una domanda di mercato enorme, e un conseguente devastante taglio del "pau brasil" nelle foreste brasiliane.

In poco meno di un secolo, già non c'erano più alberi in numero sufficiente per supplire alla domanda, anche se esemplari continuavano a essere abbattuti occasionalmente per la raccolta del legno. Con la fine del taglio del "pau brasil", il pericolo di estinzione non sparì. Le attività economiche che seguirono, come la coltivazione della canna da zucchero e del caffè, e la crescente pressione demografica furono causa del disboscamento della Mata Atlântica. Così, l'habitat naturale della specie si restrinse drasticamente.

Ma sotto il comando dell'Imperatore Dom Pedro II, vaste aree della Mata Atlântica, soprattutto nello Stato di Rio, furono recuperate e una parziale presa di coscienza ecologica frenò il disboscamento. Nel frattempo, il "pau brasil" era un albero già considerato estinto.

Nel XX secolo, la società brasiliana prese coscienza del fatto che il "pau brasil", un simbolo del paese, era in pericolo di estinzione, e furono lanciate con relativo successo delle iniziative per riprodurre la pianta a partire dalle sementi e utilizzarla in progetti di recupero forestale.

Oggi, il "pau brasil" è diventato un albero ornamentale. È ancora incerto se il suo habitat naturale sarà nuovamente devastato, ma la sopravvivenza della specie sembra assicurata nei giardini e nei parchi.

Brazilwood or Pau-Brasil, sometimes known as Pernambuco (Caesalpinia echinata syn. Guilandina echinata (Lam.) Spreng.) is a Brazilian timber tree. This plant has a dense, orange-red wood (which takes a high shine), and it is the premier wood used for making bows for string instruments from the violin family. The wood also yields a red dye called brazilin, which oxidizes to brazilein.

When Portuguese explorers found these trees of a deep red hue inside on the coast of South America, they used the name pau-brasil to describe them. Pau is Portuguese for "wood", and brasil is said to have come from brasa, Portuguese for "ember". This name had been earlier used to describe a different species of tree which was found in Asia and other places and which also produced red dye; but the South American trees soon became the better source of red dye. Brazilwood trees were such a large part of the exports and economy of the land that the country which sprang up in that part of the world took its name from them and is now called Brazil.

Botanically, several tree species are involved, all in the family Fabaceae (the pulse family). The term "Brasilwood" is most often used to refer to the species Caesalpinia echinata, but it is also applied to other species. This Caesalpinia echinata is also known as Pau-de-Pernambuco (named after the state of Pernambuco in the Nordeste [north-east] region of Brazil).

In the bow making business, the best-quality wood bows are made from Caesalpinia echinata, commonly known in the trade as "Pernambuco Wood"; bows of lesser quality wood are made from other tropical species, often called "Brazilwood". Thus, the terms "Pernambuco" and "Brazilwood" — as used in the stringed instruments bows — refer to completely different species. Examples of "Brazilwood" species used for bows include Pink Ipê (Tabebuia impetiginosa), Massaranduba (Manilkara bidentata) and Palo Brasil (Haematoxylum brasiletto).

In the 15th and 16th centuries, brazilwood was highly valued in Europe and quite difficult to get. Coming from Asia, it was traded in powder form and used as a red dye in the manufacture of luxury textiles, such as velvet, in high demand during the Renaissance. When Portuguese navigators discovered present-day Brazil, on April 22, 1500, they immediately saw that brazilwood was extremely abundant along the coast and in its hinterland, along the rivers. In a few years, a hectic and very profitable operation for felling and transporting by shipping all the brazilwood logs they could get was established, as a crown-granted Portuguese monopoly. The rich commerce which soon followed stimulated other nations to try to harvest and smuggle brazilwood contraband out of Brazil, or even corsairs attacking loaded Portuguese ships in order to steal their cargo. For example, the unsuccessful attempt of a French expedition led by Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon, vice-admiral of Brittany and corsair under the King, in 1555, to establish a colony in present-day Rio de Janeiro (France Antarctique) was motivated in part by the bounty generated by economic exploitation of brazilwood. In addition, this plant is also cited in Flora Brasiliensis by Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius.

Excessive exploitation led to a steep decrease in the number of brazilwood trees in the 18th century, causing the collapse of this economic activity. Presently, the species is nearly extinct in most of its original range. Brazilwood is listed as an endangered species by the IUCN, and it is cited in the official list of endangered flora of Brazil. The trade of brazilwood is likely to be banned in the immediate future, creating a major problem in the bow-making industry which highly values this wood. The International Pernambuco Conservation Initiative (IPCI), whose members are the bowmakers who rely on pernambuco for their livelihoods, is working to replant it. IPCI is advocating the use of other woods for violin bows as it raises money to plant pernambuco seedlings. The shortage of pernambuco has also helped the carbon fiber bow industry to thrive.

Caesalpinia coriaria

Caesalpinia pulcherrima