Lessico

Fidia

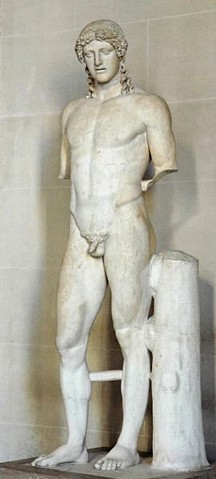

Copia

romana in marmo del II secolo dC

dell'Apollo tipo Kassel – Parigi Louvre

In greco Pheidías,

in latino Phidias. Scultore greco nato ad Atene poco prima o poco dopo

il 500 aC. Fu allievo di Egia (scultore ateniese operante tra il 490 e il 460

aC) e attivo in varie città greche, ma soprattutto ad Atene, dove diede

espressione artistica ai grandi progetti dell'età di Pericle, uomo politico

ateniese (? 495 aC -Atene 429). Scarse sono le notizie sulla sua vita, e

discordanti quelle relative alla sua morte: secondo alcuni in carcere ad

Atene, accusato dapprima del furto di parte dell'oro destinato alla

costruzione dell’Atena Parthènos, e poi di empietà per essersi

ritratto con Pericle sullo scudo della dea; secondo altri a Olimpia (antico

centro religioso greco dell'Elide![]() , nel

Peloponneso nord-occidentale), dove si sarebbe rifugiato dopo esser fuggito da

Atene.

, nel

Peloponneso nord-occidentale), dove si sarebbe rifugiato dopo esser fuggito da

Atene.

Eseguì numerose e celebrate opere, in vari materiali e con le più svariate tecniche, eccellendo sia nella rappresentazione del nudo sia nella resa del panneggio leggero e trasparente sui corpi (il cosiddetto panneggio bagnato). Si conoscono da copie l'Apollo Parnópios, statua bronzea eretta sull'Acropoli di Atene e nota nel tipo detto “Apollo di Kassel”; l'Atena Lemnia, pure sull'Acropoli, identificata in un torso di Dresda e in una testa di Bologna; l'Anadumeno di Olimpia, bronzeo, riconosciuto nel tipo Farnese in marmo del British Museum di Londra; l'Amazzone di Efeso, creata in gara con Policleto e Cresila, ricostruita nel Museo dei Gessi dell'Università di Roma dalla copia Mattei e da una testa da Villa Adriana; l'Anacreonte, identificato con la statua Borghese di Copenaghen.

Altre

opere sono note solo dalle fonti (l'Atena crisoelefantina di Pellene;

la colossale Atena Pròmachos sull'Acropoli ateniese; il Donario

di Maratona a Delfi). Ma la realizzazione più grandiosa di Fidia fu la

sistemazione urbanistica dell'Acropoli di Atene e in particolare del Partenone

(inizio dei lavori nel 447 aC), di cui eseguì con aiuti la decorazione

scultorea (frontoni , metope e grande fregio) conservata per la maggior parte

al British Museum. Di Fidia era anche il colossale simulacro crisoelefantino

della dea, la famosa Atena Parthènos (438 aC), di cui si ha eco

sbiadita in statuette e copie parziali (la testa è riprodotta in una gemma

dovuta ad Aspasios, incisore romano dell'età di Augusto![]() ).

Crisoelefantina era anche la statua di Zeus per il tempio di Olimpia, nota da

monete adrianee, da gemme e da una testa di Cirene. L'originalità del

linguaggio plastico fidiaco innovò completamente la scultura greca dandole

l'impronta della “classicità”, ed ebbe un'influenza enorme anche

sull'arte di epoche molto più tarde.

).

Crisoelefantina era anche la statua di Zeus per il tempio di Olimpia, nota da

monete adrianee, da gemme e da una testa di Cirene. L'originalità del

linguaggio plastico fidiaco innovò completamente la scultura greca dandole

l'impronta della “classicità”, ed ebbe un'influenza enorme anche

sull'arte di epoche molto più tarde.

Fidia

Atena

Lemnia

Staatliche Museum Albertinum - Dresden

Fidia (in greco Pheidías; Atene, 490 aC circa – Atene, 430 aC circa) è stato uno scultore, pittore e architetto greco antico. Delle sue opere originali, peraltro, sono giunti ai nostri giorni ben pochi resti. Le conoscenze che si hanno sulla sua opera si basano prevalentemente sulla descrizione di scrittori antichi e sulle copie rinvenute di alcune sue sculture, e i rinvii iconografici alle sue opere desumibili da monete e gemme. Si sa solo che Fidia eccelleva nella perfezione e nella plasticità delle forme, con una perfetta espressione di ideale di eterna bellezza.

Della sua vita si conoscono

pochi dettagli: sappiamo che nacque ad Atene poco dopo la battaglia di

Maratona![]() (490 aC), fu allievo di

Egia, scultore ateniese della scuola peloponnesiaca operante tra il 490 e il 460 aC, e conobbe anche il pittore Polignoto; insieme a

Mirone e Policleto apprese ad Argo da Agelada le tecniche della scultura in

bronzo.

(490 aC), fu allievo di

Egia, scultore ateniese della scuola peloponnesiaca operante tra il 490 e il 460 aC, e conobbe anche il pittore Polignoto; insieme a

Mirone e Policleto apprese ad Argo da Agelada le tecniche della scultura in

bronzo.

La sua prima opera conosciuta è la colossale statua bronzea di Atena Promachos eretta sull’Acropoli di Atene nel 460 aC. In seguito Pericle lo scelse per sovraintendere ai lavori del nuovo tempio dedicato ad Atena (il celebre Partenone). La colossale statua di culto crisoelefantina (rivestita d’oro e di avorio) dell’Atena Parthenos fu dedicata nel 438 aC. Realizzò i modelli per le sculture dei due frontoni, per le 92 metope del fregio esterno e per il fregio che decora il muro della cella, che vennero eseguite da molti suoi discepoli e allievi (i resti si possono ammirare sui due frontoni, comprese 19 delle 92 metope e il fregio che raffigura la processione delle Panatenee) e quella dei Propilei, il monumentale ingresso alla città fortificata. La maggior parte delle statue rappresentate sono realizzate con la tecnica del panneggio bagnato ideato dallo stesso Fidia. Quasi tutte le opere rinvenute sono conservate al British Museum e sono conosciute col nome di “Collezione marmi di Elgin”.

Nel 438 aC, in seguito all'incendio della sua

dimora, si sposta a Olimpia, dove riceve l'incarico di realizzare una nuova e

colossale statua crisoelefantina di Zeus Olimpio, situata all’interno del

tempio della città di Olimpia e annoverata tra le sette meraviglie del mondo;

la statua, purtroppo, è andata perduta e, solo grazie alla descrizione di

Pausania![]() , nella sua “Periegesi della Grecia”, è

possibile farsene un'idea.

, nella sua “Periegesi della Grecia”, è

possibile farsene un'idea.

Fidia fu anche ideatore di molte altre sculture,

come ad esempio il gruppo bronzeo che rappresenta alcuni eroi greci con al

centro il generale Milziade![]() . Sono a lui attribuite altre statue dedicate ad

Atena, una delle quali, nota da copie, ha preso il nome di Atena Lemnia.

. Sono a lui attribuite altre statue dedicate ad

Atena, una delle quali, nota da copie, ha preso il nome di Atena Lemnia.

Rientrato ad Atene da Olimpia, nel 433 aC fu vittima delle lotte politiche ateniesi: per screditare il suo protettore, Pericle. Fu accusato di essersi appropriato di una parte dell’oro da utilizzare per l’Atena Parthenos. Fidia riuscì a provare la sua innocenza solo smontando e facendo pesare le parti d’oro della statua. Prosciolto da quest'accusa, fu però nuovamente accusato, questa volta di empietà, per essersi raffigurato insieme a Pericle sullo scudo della dea. Venne prima imprigionato e, quindi, esiliato a Olimpia, dove lo coglierà la morte.

Lo stile di Fidia si caratterizza per una rappresentazione realistica dell’anatomia umana, idealizzata con la maestà e serenità delle figure. Realizza così una sintesi tra la potenza arcaica e l’armonia classica. I suoi bassorilievi sono notevoli per rigore compositivo e senso ritmico, staccandosi dalla staticità dei grandi fregi orientali: nella processione delle Panatenaiche vengono inseriti dei contrappunti, come personaggi girati all’indietro, e la composizione si articola per linee curve, convergenti e divergenti. I personaggi sono ben distinti e scalati, dando l’impressione dell’affollamento di molti individui e non di un ammasso indifferenziato. È da rilevare inoltre la grande cura dei particolari (nel frontone orientale, raffigurante la nascita di Atena, si distinguono le vene sporgenti del cavallo di Selene).

The

Athena Parthenos signed by Antiochos

1st century BC - Palazzo Altieri, Rome

Phidias (or Pheidias; in ancient Greek, Pheidías; c.480 BC – c.430 BC), son of Charmides was an ancient Greek sculptor, painter and architect, universally regarded as the greatest of all Classical sculptors. Although no original works in existence can be confidently attributed to him with certainty, numerous Roman copies in varying degrees of supposed fidelity are known to exist. Phidias designed the statues of the goddess Athena on the Athenian Acropolis (Athena Parthenos inside the Parthenon and the Athena Promachos) and the colossal seated Statue of Zeus at Olympia in the 5th century BC. The Athenian works were apparently commissioned by Pericles in 447 BC. Pericles used the money from the maritime League of Delos to pay Phidias for his work.

There are varying accounts of his training. Hegias of Athens, Ageladas of Argos, and the Thasian painter Polygnotus, have all been regarded as his teachers. In favour of Ageladas it may be said that the influence of the many Dorian schools is certainly to be traced in some of his work.

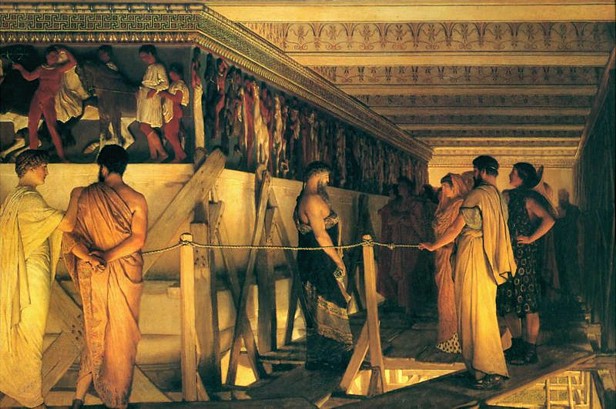

Phidias

showing the frieze of the Parthenon to his friends - 1868

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912) - Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

Painting shows at left the North frieze slab XLVII and the West frieze Slabs I and up visible at right. Among the spectators, critics have identified Pericles, the bearded man facing Phidias. Next to him is his mistress, Aspasia. In the foreground stands a boy, Alcibiades, with his lover, Socrates.

Of his life we know little apart from his works. It is known, however, that he was Athenian and studied at Hageladas school in Argos. His first commission was a group of national heroes with Miltiades as a central figure. The famous statesman Pericles also ordered several sculptures for Athens from him. There are two divergent accounts of his death. According to Plutarch, he was made an object of attack by the political enemies of Pericles, and died in prison at Athens, but according to Philochorus, as quoted by a scholiast on Aristophanes, he fled to Elis, where he made the great statue of Zeus for the Eleans, but was afterwards put to death by them. For several reasons the first of these tales is preferable: it would not have been possible for him to have died in prison immediately after the creation of the Athena Parthenos on the Acropolis, as he made the Zeus of Olympia after his involvement with the Parthenon.

In his Life of Pericles, Plutarch gives an account of the vast artistic activity which went on at Athens while that statesman was in power. Phidias used the money furnished by the Athenian allies for defence against Persia instead on decorating Athens. It was very fortunate that after the time of Xerxes, Persia made no deliberate attempt against Greece. "In all these works," says Plutarch, "Phidias was the adviser and overseer of Pericles." Phidias introduced his own portrait and that of Pericles on the shield of his Athena Parthenos statue. And it was through Phidias that the political enemies of Pericles struck at him. It thus abundantly appears that Phidias was closely connected with Pericles, and a dominant spirit in the Athenian art of the period. But it is not easy to go beyond this general assertion into details.

It is important to observe that in resting the fame of Phidias upon the sculptures of the Parthenon we proceed with little evidence. In the Hippias Major, Plato ascribes them to him, though he is said to seldom, if ever, have executed works in marble. In antiquity he was celebrated for his statues in bronze, and his chryselephantine works (statues made of gold and ivory). Plutarch tells us that he superintended the great works of Pericles on the Acropolis, but this phrase is vague; inscriptions prove that the marble blocks intended for the pedimental statues of the Parthenon were not brought to Athens until 434 BC, which was probably after the death of Phidias. And there is a marked contrast in style between these statues and the certain works of Phidias. It is therefore probable that most if not all of the sculptural decoration of the Parthenon was the work of pupils of Phidias, such as Alcamenes and Agoracritus, rather than his own.

The earliest of the great works of Phidias were dedications in memory of Marathon, from the spoils of the victory. At Delphi he erected a great group in bronze including the figures of Apollo and Athena, several Attic heroes, and Miltiades the general. On the acropolis of Athens he set up a colossal bronze statue of Athena, the Athena Promachos, which was visible far out at sea. At Pellene in Achaea, and at Plataea he made two other statues of Athena, as well as a statue of Aphrodite in ivory and gold for the people of Elis.

Among the ancient Greeks themselves two works of Phidias far outshone all others, and were the basis of his fame; the colossal chryselephantine figures in gold and ivory of Zeus at Olympia and of Athena Parthenos at Athens, both of which belong to about the middle of the 5th century BC. Of the Zeus we have unfortunately lost all trace save small copies on coins of Elis, which give us but a general notion of the pose, and the character of the head. The god was seated on a throne, every part of which was used as a ground for sculptural decoration. His body was of ivory, his robe of gold. His head was of somewhat archaic type: the Otricoli mask which used to be regarded as a copy of the head of the Olympian statue is certainly more than a century later in style. Of the Athena Parthenos two small copies in marble have been found at Athens which have no excellence of workmanship, but have a certain evidential value as to the treatment of their original.

Our actual knowledge of the works of Phidias is very small. There are many stately figures in the Roman and other museums which clearly belong to the same school as the Parthenos; but they are copies of the Roman age, and not to be trusted in point of style. Adolf Furtwangler proposed to find in a statue of which the head is at Bologna, and the body at Dresden, a copy of the Lemnian Athena of Phidias; but his arguments (Masterpieces, at the beginning) are anything but conclusive. Much more satisfactory as evidence are some 5th century torsos of Athena found at Athens. The very fine torso of Athena in the École des Beaux-Arts at Paris, which has unfortunately lost its head, may perhaps best serve to help our imagination in reconstructing the original statue.

Ancient critics take a very high view of the merits of Phidias. What they especially praise is the ethos or permanent moral level of his works as compared with those of the later "pathetic" school. Demetrius calls his statues sublime, and at the same time precise. That he rode on the crest of a splendid wave of art is not to be questioned: but it is to be regretted that we have no morsel of work extant for which we can definitely hold him responsible except for one.

In 1958 archaeologists found the workshop at Olympia where Phidias assembled the gold and ivory Zeus. There were still some shards of ivory at the site, moulds and other casting equipment, and the base of a black glaze drinking cup engraved "I belong to Phidias."

The golden ratio has been represented by the Greek letter(phi), after Phidias, who is said to have employed it. The golden ratio is an irrational number close to 1.6181, which when studied has special mathematical properties. The golden spiral is also said to hold certain aesthetic values, which is perhaps why Phidias used it. The Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh used the name of Phidias in his poem Plough horses.

Athéna

dite de Varvakeion

meilleure copie de l'Athéna Parthénos chryséléphantine

Musée national archéologique d'Athènes

Phidias (Athènes, v. 490 – Olympie, ap. 430), est un sculpteur du premier classicisme grec. On dispose de peu de détails sur la vie de Phidias. Né à Athènes peu après la bataille de Marathon, il est l'élève d'Hêgias et apprend la technique du bronze à l'école d'Argos, en même temps que Myron et Polyclète. Il semble avoir véritablement commencé son activité en -464.

Sa première grande œuvre est une colossale Athéna Promachos, pour l'Acropole, en 460. Il est ensuite choisi par Périclès pour exécuter des statues pour le Parthénon, mais aussi pour superviser l'ensemble des travaux de sculpture. Il réalise lui-même la statue chryséléphantine, c’est-à-dire faite d'or et d'ivoire, d'Athéna Parthénos, dédiée en 438, et réalise des maquettes pour les deux frontons, les 92 métopes et la frise. Il surveille étroitement leur exécution par son atelier, avant de partir en 437 à Élis et Olympie, où il réalise son Zeus chryséléphantin, l'une des Sept merveilles du monde.

Quand il rentre à Athènes en 433, il est victime d'une manœuvre destinée à discréditer, à travers lui, son protecteur Périclès. Il est d'abord accusé d'avoir volé une partie de l'or de l'Athéna Parthénos. Après avoir été disculpé par une pesée des éléments en or, il est de nouveau accusé, cette fois d'impiété: il s'est en effet représenté, avec Périclès, au beau milieu de l'amazonomachie, sur le bouclier de la déesse. Jeté en prison, il est ensuite, en 430, exilé à Olympie où il y meurt.

Méduse

Rondanini attribuée à Phidias

Glyptothèque de München

Le style de Phidias, le meilleur représentant du premier classicisme, se caractérise par une représentation réaliste de l'anatomie humaine, mais idéaliste par son idéal de majesté et de sérénité. Selon l'expression d'Edmond Lévy, il réalise ainsi « une synthèse subtile de la puissance archaïque et de l'harmonie classique ». Il a aussi crée une statue d'Athéna en or en en ivoire, fierté du Parthénon.

Ses bas-reliefs sont remarquables par la rigueur de leur composition, et leur souci de rythme: se détachant du statisme des grandes frises orientales, Phidias introduit dans les scènes des contrepoints (personnages retournés, à contre-courant) et joue sur les lignes courbes, divergentes et convergentes. Il réussit à bien détacher et étager ses personnages, donnant l'impression d'une multitude d'individus et non d'un amas peu discernable. La minutie des représentations (on voit les veines saillantes du cheval de Séléné sur le fronton oriental représentant la naissance d'Athéna) fait de chacun des sujets de véritables sculptures.

On lui prête également une légende: Phidias participait à un concours de sculpture d'une statue d'Athéna qui serait disposée à Athènes, à quatre mètres du sol. Tous les artistes présentèrent leurs œuvres, et Phidias, déjà très célèbre, la découvrit en dernière. Ce fut un tollé, les Athéniens trouvant difforme et laide la statue proposée par Phidias. Il leur demande alors de hisser cette statue sur le réceptacle prévu à cet effet. Une fois disposée, les déformations de la statue disparaissaient pour laisser l'illusion d'une Athéna aux formes parfaitement respectées. Ce fut évidemment et unanimement cette statue qui fut choisie par les Athéniens.