Lessico

Frassino e Manna

Fraxinus ha un'etimologia assai variopinta e variabile che non vale la pena riportare. Frassino è il nome di piante appartenenti al genere Fraxinus della famiglia Oleacee, originarie dell'emisfero settentrionale e per la maggior parte dell'America.

Sono piante arboree con foglie caduche, opposte, di norma pennato-composte, fiori piccoli, riuniti in racemi, e frutti a samara. Sàmara è il frutto secco indeiscente, con pericarpo addossato al seme, come l'achenio, ma provvisto di un'ala membranosa che lo circonda in tutto o in parte e che serve da organo di sostenimento nell'aria, favorendo la disseminazione a opera del vento o anemofila. La sàmara è presente nell'acero, nell'olmo, nel frassino e altre piante ancora.

In Italia trovano due specie di frassino: Fraxinus ornus, detto frassino da manna o orniello, e Fraxinus excelsior, il frassino comune o frassino propriamente detto.

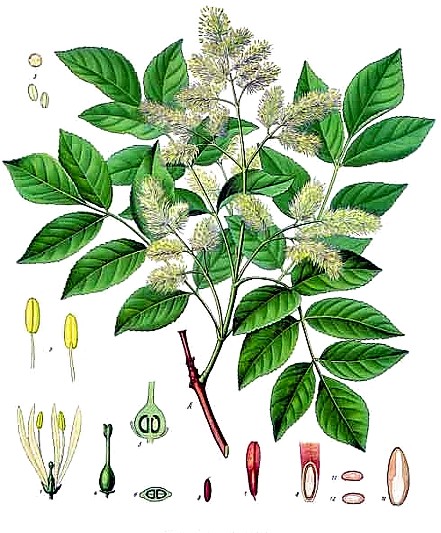

Il Fraxinus ornus della famiglia delle Oleaceae, conosciuto come Orniello o Orno e chiamato volgarmente anche frassino da manna o albero della manna nelle zone di produzione della manna; è un albero o arbusto di 4-8 m di altezza, spesso ridotto a cespuglio. È diffuso nell'Europa meridionale e nell'Asia Minore. Il limite settentrionale della specie è l'arco alpino e la valle del Danubio, mentre il limite orientale è la Siria e l'Anatolia.

In Italia è comunissimo in tutta la penisola, dalla fascia prealpina del Carso fino ai laghi lombardi. Penetra nelle valli principali fino al cuore delle Alpi risalendo le pendici montane fin verso i 600-700 m di altitudine. Nella pianura padana è quasi assente, torna a popolare gli Appennini settentrionali e centrali, in particolare sulla costa adriatica.

Specie piuttosto termofila e xerofila preferisce le zone di pendio alle vallette ombrose e fresche. In Sicilia si spinge fino ai 1400 m di altitudine. Nelle regioni occidentali diviene progressivamente rara, fino a formare tipi localizzati, di cui non è sicura però la distinzione. Abita preferibilmente boscaglie degradate nell'area submediterranea.

L'orniello ha tronco eretto leggermente tortuoso con rami opposti ascendenti con corteccia liscia grigiastra, opaca, gemme rossicce tomentose. La chioma ampia è formata da foglie caduche opposte, imparipennate con 5-9 segmenti, più spesso 7, di cui i laterali misurano 5-10 cm, ellittici o lanceolati brevemente picciolati, larghi un terzo della loro lunghezza. Il segmento centrale, invece, si presenta largo circa la metà della sua lunghezza ed è obovato; la faccia superiore è di un bel colore verde, mentre quella inferiore è più chiara e pelosa lungo le nervature.

Le infiorescenze sono a forma di pannocchie, generalmente apicali e ascellari; i fiori generalmente ermafroditi e profumati, con un breve pedicello, possiedono un calice campanulato con quattro lacinie lanceolate e diseguali di colore verde-giallognolo, la corolla ha petali bianchi leggermente sfumati di rosa lineari di 5-6 mm di lunghezza. Il frutto è una samara oblunga cuneata alla base ampiamente alata all'apice lunga 2-3 cm con un unico seme compresso di circa un centimetro.

L'orniello è una specie interessante per la silvicoltura, in quanto può essere considerato una specie pioniera, resistendo a condizioni climatiche difficili, adatta quindi al rimboschimento di terreni aridi e siccitosi. Viene coltivato in Sicilia e Calabria per la produzione della manna, in Toscana nei vigneti viene frequentemente utilizzata come sostegno ai filari di vite. Si moltiplica facilmente con la semina.

Avversità

Cantaride - adulti di Lytta vesicatoria attaccano le foglie divorando solo il lembo e lasciando intatte le nervature.

Ciono - le larve di Cionus fraxini rodono le gemme e le foglie lasciando intatta solo l'epidermide superiore che ben presto imbrunisce e dissecca; gli adulti attaccano in primavera le giovani gemme.

Ilesino - gli adulti di Lepersinus fraxini scavano gallerie nella corteccia che appare perforata in più punti screpolandosi; col tempo si forma una fitta rete di piccole gallerie che indeboliscono la parte di pianta attaccata.

Tentrenide - le larve di Tomostethus melanopygus divorano le foglie lasciando intatte le sole nervature con grave defogliazione della chioma.

Carie del legno - i funghi Fomes ignarius e Fomes fomentarius attaccano il legno profondamente con perdita di consistenza e assunzione di un aspetto spugnoso biancastro per la distruzione della lignina; i corpi fruttiferi dei parassiti sono visibili all'esterno dei tronchi attaccati e sono a forma di mensola o zoccolo. Stesso tipo di danno causa la Schizophthora omnivora con corpi fruttiferi a forma di orecchiette grigiastre.

Marciume delle piantine - il fungo Phytophthora omnivora colpisce le giovani piantine nei semenzai con lesioni necrotiche del colletto.

Oidio o Mal bianco - i funghi Microsphaera alni e Phyllactinia sufflata attaccano le foglie e i giovani rametti verdi, provocando chiazze biancastre polverulenti a consistenza feltrosa che nel tempo imbruniscono disseccando le parti colpite.

Usi

Nella silvicoltura per il rimboschimento di suoli poveri, aridi, calcarei o argillosi.

Come pianta ornamentale in parchi e giardini di grandi dimensioni, anche su terreni secchi e poco profondi.

Come pianta officinale e medicinale.

Per l'estrazione di tannini dalla corteccia.

Utilizzando le foglie come foraggio per il bestiame in zone povere di pascoli.

Per la produzione di legname: il legno di Orniello ha il durame bruno chiaro, con anelli ben distinti e provvisti di grossi vasi nella zona primaverile, è elastico e resistente. Facilmente lavorabile, viene utilizzato industrialmente per la produzione di mobilio, per attrezzi vari, per lavori al tornio e come ottimo combustibile.

Le foglie secche e triturate e i frutti posti in infuso in acqua bollente forniscono il tè di frassino.

Le foglie fermentate con acqua e saccarosio servono per preparare bevande alcoliche.

Il succo estratto dopo incisione della corteccia (manna) viene usato come blando lassativo in pediatria

Il decotto di manna, sostanza solida bianca-giallastra ricavata dal succo zuccherino che sgorga dalle lesioni della corteccia e che si rapprende rapidamente a contatto dell'aria, raccolta in estate, è un blando purgante. Ha anche proprietà bechiche e anticatarrali; può essere usato come collirio nelle congestioni oculari. Pezzetti di manna sciolti in bocca lentamente hanno proprietà espettoranti. L'infuso delle foglie raccolte a fine primavera inizio estate ed essiccate al sole, viene utilizzato come emolliente.

Fraxinus ornus (Manna Ash) is a species of Fraxinus native to southern Europe and southwestern Asia, from Spain and Italy north to Austria and the Czech Republic, and east through the Balkans, Turkey, and western Syria to the Lebanon.

It is a medium-sized deciduous tree growing to 15–25 m tall with a trunk up to 1 m diameter. The bark is dark grey, remaining smooth even on old trees. The buds are pale pinkish-brown to grey-brown, with a dense covering of short grey hairs. The leaves are in opposite pairs, pinnate, 20-30 cm long, with 5-9 leaflets; the leaflets are broad ovoid, 5-10 cm long and 2-4 cm broad, with a finely serrated and wavy margin, and short but distinct petiolules 5–15 mm long; the autumn colour is variable, yellow to purplish. The flowers are produced in dense panicles 10–20 cm long after the new leaves appear in late spring, each flower with four slender creamy white petals 5–6 mm long; they are pollinated by insects. The fruit is a slender samara 1.5-2.5 cm long, the seed 2 mm broad and the wing 4–5 mm broad, green ripening brown.

Cultivation and uses

A sugary extract from the sap is extracted by making a cut in the bark; this was compared in late mediaeval times (attested by c.1400) with the biblical manna, giving rise to the English name of the tree.

It is frequently grown as an ornamental tree in Europe north of its native range, grown for its decorative flowers (the species is also sometimes called "Flowering Ash"). Some cultivated specimens are grafted on rootstocks of Fraxinus excelsior, with an often very conspicuous change in the bark at the graft line to the fissured bark of the rootstock species.

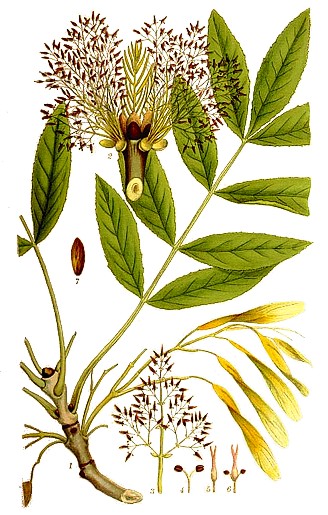

Il Fraxinus excelsior, della famiglia delle Oleaceae, noto col nome comune di Frassino maggiore o Frassino comune, è una specie diffusa dall'Asia minore all'Europa, è un albero di notevoli dimensioni fino a 40 m di altezza. Lo si trova in tutta la penisola italiana, meno sporadicamente nell'Appennino centro settentrionale, dove prospera nelle zone fitoclimatiche del Castanetum, del Fagetum e più raramente del Lauretum. Ha il tronco dritto e cilindrico la corteccia dapprima liscia e olivastra successivamente diventa grigio-brunastra e screpolata longitudinalmente. Le gemme sono vellutate e di colore nerastro, ha grandi foglie caduche composte imparipennate formate da 9-11 paia di foglioline sessili opposte e minutamente seghettate di colore verde cupo e lucente sulla pagina superiore, più chiare su quella inferiore, con fiori ermafroditi, riuniti in infiorescenze ascellari a pannocchia, piccoli, di colore verdastro, che compaiono prima delle foglie, privi di calice e di corolla con stami brevissimi sormontati da un'antera globosa di colore porpora scuro. I frutti sono samare bislunghe a forma variabile con base arrotondata o troncata con un unico seme e riunite in grappoli pendenti.

Il Frassino maggiore richiede terreni fertili, umidi ricchi di humus e profondi, viene governato a Fustaia con turni di 70-80 anni e raramente a Ceduo, si moltiplica facilmente con la semina o trapiantando piantine di 2-4 anni. Si deve prevedere continua e tempestiva lotta ai parassiti animali e fungini. Per maggiori informazioni consultate www.ilfrassino.it

Il decotto delle giovani radici raccolte in primavera o in autunno ha proprietà antidropica. Il decotto della polvere ottenuta dalla corteccia dei giovani rami di 3-4 anni raccolta alla ripresa vegetativa e fatta essiccare all'ombra, ha proprietà toniche, eupeptiche, antidiarroiche e febbrifughe; per uso esterno viene utilizzato come cataplasma dalle proprietà astringenti. L'infuso delle foglie raccolte a fine primavera inizio estate ed essiccate al sole, viene utilizzato come emolliente. L'infuso di frutti raccolti d'estate è diuretico, lassativo, sudorifero, antireumatico, con proprietà curative della gotta per l'eliminazione degli acidi urici e nella cura delle cistiti

Il legno di Frassino maggiore è elastico e resistente, il peso specifico è 0,96 da fresco; 0,72 da stagionato e 0,66 da secco. Facilmente lavorabile, viene utilizzato industrialmente per la produzione di compensati, pavimenti, mobili, timoni per imbarcazioni da diporto, manici per attrezzi e parti di strumenti musicali.

Male flowers

Fraxinus excelsior (Ash; also European Ash or Common Ash on occasion to distinguish it from other ash species), is a species of Fraxinus native to most of Europe with the exception of northern Scandinavia and southern Iberia, and also southwestern Asia from northern Turkey east to the Caucasus and Alborz mountains. The northernmost location is in the Trondheimsfjord region of Norway.

It is a large deciduous tree growing to 20-35 m (exceptionally to 46 m) tall with a trunk up to 2 m (exceptionally to 3.5 m) diameter, with a tall, domed crown. The bark is smooth and pale grey on young trees, becoming thick and vertically fissured on old trees. The shoots are stout, greenish-grey, with jet black buds. The leaves are 20-35 cm long, pinnate compound, with 7-13 leaflets, the leaflets 3–12 cm long and 0.8–3 cm broad, sessile on the leaf rachis, and with a serrated margin. The leaves are often among the last to open in spring, and the first to fall in autumn if an early frost strikes; they have no marked autumn colour, often falling dull green. The flowers open before the leaves, the female flowers being somewhat longer than the male flowers; they are dark purple, and without petals, and are wind-pollinated. Both male and female flowers can occur on the same tree, but it is more common to find all male and all female trees; a tree that is all male one year can produce female flowers the next, and similarly a female tree can become male. The fruit is a samara 2.5-4.5 cm long and 5–8 mm broad, often hanging in bunches through the winter; they are often called 'ash keys'.

It is readily distinguished from other species of ash in that it has black buds, unlike the brown or grey buds of most other ashes.

Ash occurs on a wide range of soil types, but is particularly associated with basic soils on calcareous substrates. The most northerly ashwood in Britain is on limestone at Rassal, Wester Ross, latitude 57.4278 N. A number of Lepidoptera use the species as a food source. See Lepidoptera which feed on ashes.

The resilience and rapid growth made it an important resource for smallholders and farmers. It was probably the most versatile wood in the countryside with wide-ranging uses. Until the Second World War the trees were often coppiced on a ten year cycle to provide a sustainable source of timber for fuel and poles for building and woodworking.

Wood

The colour of the wood ranges from creamy white through light brown, and the heart wood may be darker olive-brown. Ash timber is hard, tough and very hard-wearing, with a coarse open grain. It lacks oak's natural resistance to decay, and is not as suitable for posts buried in the ground. Because of its high flexibility, shock-resistance and resistance to splitting Ash wood is the traditional material for bows, tool handles, especially for hammers and axes, tennis rackets and snooker cues, although American hickory, from trees of the genus Carya arguably performs even better for these purposes. Ash is valuable as firewood because it burns well even when 'green' (freshly cut). Ash was coppiced, often in hedgerows, and evidence in the form of some huge boles with multiple trunks emerging at head height can still be see in parts of Britain. In Northumberland crab and lobster pots (traps) sometimes known as 'creeves' by local people are still made from ash sticks. Because of its elasticity European Ash wood was commonly used for walking sticks. Poles were cut from a coppice and the ends heated in steam. The wood could then be bent in a curved vice to form the handle of the walking stick. The light colour and attractive grain of ash wood make it popular in modern furniture such as chairs, dining tables, doors and other architectural features and hardwood flooring, although the wood is often popularly stained jet black.

Succo rappreso e più o meno indurito che si ottiene da varie specie di piante del genere Fraxinus, in particolare dal Fraxinus ornus (orniello), mediante apposite incisioni praticate nella corteccia degli esemplari di 8-20 anni, durante la stagione calda e secca.

L'essudato che ne cola si rapprende lungo il fusto in forma di stalattiti (manna in cannoli, manna eletta), o di gocce (manna in grani) o si raccoglie alla base del tronco (manna in sorte), in appositi recipienti. È una sostanza bianco-giallastra, untuosa, con lucentezza grassa, più o meno molle secondo il grado di umidità e la temperatura, di odore tenue e sapore dolciastro.

Il suo componente principale è la mannite, che vi è contenuta in proporzioni variabili fino all'80-90%. Si usa in medicina come leggero lassativo o per preparare infusi e sciroppi purgativi; serve inoltre per la preparazione della mannite. La mannite, detta anche mannitolo, è un alcol esavalente contenuto nella manna e in altri vegetali, dove si forma per riduzione enzimatica del D-mannosio. In farmacia viene adoperata come eccipiente delle forme farmaceutiche orali. In medicina trova impiego come purgante, specie nell'infanzia, come diuretico e come blando espettorante. Questa manna non è da confondere con quella citata dalla Bibbia.

La manna viene citata nella

Torah![]() , conosciuta nella Religione

Cristiana come l'Antico Testamento, in riferimento al cibo di cui si nutrì il

popolo d'Israele durante il cammino dei 40 anni nel deserto dopo l'uscita e la

liberazione dalla schiavitù in Egitto. Si racconta come questo pane degli

angeli derivasse direttamente dal regno celeste e spirituale e fosse prodotto

dagli angeli dell'ordine delle Chayyot, usando per questo significato la

metafora del sudore delle Chayyot e di una produzione effettuata da Dio sempre

con gli angeli avvenuta attraverso delle macine celesti.

, conosciuta nella Religione

Cristiana come l'Antico Testamento, in riferimento al cibo di cui si nutrì il

popolo d'Israele durante il cammino dei 40 anni nel deserto dopo l'uscita e la

liberazione dalla schiavitù in Egitto. Si racconta come questo pane degli

angeli derivasse direttamente dal regno celeste e spirituale e fosse prodotto

dagli angeli dell'ordine delle Chayyot, usando per questo significato la

metafora del sudore delle Chayyot e di una produzione effettuata da Dio sempre

con gli angeli avvenuta attraverso delle macine celesti.

« E, evaporato lo strato di rugiada, apparve sulla superficie del deserto qualcosa di minuto, di granuloso, fine come brina gelata in terra. A tal vista i figli d'Israele si chiesero l'un l'altro: <<Che cos'è questo?>> perché non sapevano che cosa fosse. E Mosè disse loro: <<Questo è il pane che il Signore vi ha dato per cibo. Ecco ciò che ha prescritto in proposito il Signore: ne raccolga ognuno secondo le proprie necessità, un omer a testa, altrettanto ciascuno secondo il numero delle persone coabitanti nella stessa tenda così ne prenderete>>. Così fecero i figli d'Israele e ne raccolsero chi più chi meno. Misurarono poi il recipiente del contenuto di un omer; ora colui che ne aveva molto non ne ebbe in superfluo e colui che ne aveva raccolto in quantità minima non ne ebbe in penuria; ciascuno insomma aveva raccolto in proporzione delle proprie necessità » (Esodo 16.16-18)

Nel Libro dell'Esodo della Bibbia Ebraica vi sono altre allusioni alla manna, ma è soprattutto nella tradizione orale come nel Talmud, poi messa per iscritto, la maggior presenza di commenti in merito ad essa.

Nella Torah è paragonata al coriandolo bianco e a una frittella di miele; si racconta che il miele è 1/60 della manna, e per miele si può intendere anche il dattero o il nettare dolce di tutti i frutti. La manna compariva come un granello o come un coriandolo dopo che lo strato di rugiada si scioglieva: si doveva raccoglierla immediatamente per evitare che anch'essa si sciogliesse. Come unico sostentamento alimentare, la manna veniva lavorata in molti modi: con essa venivano fatte anche delle focacce.

Non potendo raccoglierla durante il Sabato (giorno che secondo la tradizione ebraica era destinato al riposo), Dio donava una doppia razione di manna ogni Venerdì affinché bastasse anche per il Sabato; in ricordo di ciò gli osservanti della Religione ebraica dovrebbero preparare i pasti del Sabato con almeno due pagnotte chiamate Challot: esse vengono custodite su due panni di stoffa, uno al di sopra e uno sotto, per ricordare anche il doppio strato di rugiada che ricopriva questo cibo celeste.

Ogni Ebreo che assaggiava la manna poteva percepire e gustare un sapore diverso da quello degli altri Ebrei: si parla di gusti di altri cibi.

La manna non produceva feci in quanto cibo celeste e non soggetto alla regola della generazione e della corruzione anche citata da Maimonide nel testo Guida dei Perplessi: ché non di solo pane vive l'uomo, ma di tutto ciò che esce dalla Volontà del Signore, viene commentato a proposito della manna. Vi fu però un caso citato nel Tanakh in cui la manna fatta avanzare produsse vermi.

La tradizione vuole che la manna tornerà con l'era messianica. Secondo la tradizione fu di Mosè il merito che la manna scendesse dal Cielo per il popolo d'Israele.

Manna (sometimes or archaically spelt mana) is the name of a food which, according to the Bible, was eaten by the Israelites during their travels in the desert; until they reached Canaan, the Israelites are implied by some passages in the Bible to have eaten only manna during their desert sojourn, despite the availability of milk and meat from the livestock with which they traveled, and the references to provisions of fine flour, oil, and meat, in later parts of the journey's narrative. The manna is also briefly mentioned in the Qur'an, with the Sura of the Cow, Sura of the Heights, and Sura of the Flattening, mentioning the divine supply of manna as one of the miracles with which the Israelites were favoured; these passages only describe manna as being good things which have been provided ... as sustenance.

Biblical description

Hoarfrost on grass lawn

In the description in the Book of Exodus, manna is described as appearing each morning after the dew had gone, while in the description in the Book of Numbers, manna arrived with the dew during the night; the Book of Exodus adds that manna was comparable to hoarfrost in size, and similarly had to be collected before it was melted by the heat of the sun.

Coriander seeds close-up

According to the Biblical description, manna resembled coriander seed; in the Book of Exodus, manna is described as being white in colour, while the Book of Numbers describes it as being the same colour as bdellium. According to the Book of Numbers, the Israelites ground it up and pounded it into cakes, which were then baked, resulting in something that tasted like olive oil; the Book of Exodus states that it tasted like wafers that had been made with honey. The Israelites were instructed to only eat the manna they had gathered for each day, for leftovers or storing any up for the following day resulted in manna in manna that "bred worms and stank" The exception to this occurrence was the day before the Sabbath when twice the amount of manna was gathered, which did not spoil overnight.

Textual scholars view the two descriptions of manna as deriving from different sources, with the description in the Book of Numbers being from the Jahwist text, and the description in the Book of Exodus being from the later Priestly Source. The Babylonian Talmud, however, argues instead that the differences in description were due to the taste varying depending on who ate it, with it tasting like honey for small children, like bread for youths, and like oil for the elderly; similarly classical rabbinical literature rectifies the question of whether manna came before or after dew, by arguing that the manna was sandwiched between two layers of dew, one layer of dew falling before the manna, and the other falling after it.

Identifying manna

A tamarisk tree – Tamarix aphylla - in the Levant desert

Some scholars have proposed that manna is cognate with the Egyptian term mennu, meaning food. At the turn of the 20th century, Arabs residing in the Sinai Peninsula were selling resin from the tamarisk tree as man es-simma, roughly meaning heavenly manna. Tamarisk trees (particularly Tamarix Gallica) were once comparatively extensive throughout the southern parts of the Sinai Peninsula, and their resin is similar to wax, melts in the sun, is sweet and aromatic (like honey), and has a dirty-yellow colour, fitting somewhat with the biblical descriptions of manna; however, this resin is mostly composed from sugar, so couldn't provide sufficient nutrition for a population to survive over large periods of time, and it would be very difficult for it to have been compacted to become cakes.

Black ant with a clear bubble of honeydew produced by a green aphid

In the Biblical account, the name manna is said to derive from the question man hu, seemingly meaning what is this?; but this is an Aramaic etymology not a Hebrew one. Man here is most likely to be cognate with the Arabic term man, meaning plant lice, with man hu thus meaning this is plant lice; the equation with plant lice fits with one of the two most widespread modern identifications of manna, namely that manna refers to the crystallised honeydew of certain scale insects.

Scale insects covered in waxy secretions

In the environment of a desert, such honeydew rapidly dries due to evaporation of its water content, becoming a sticky solid, and later turning whitish, yellowish, or brownish; honeydew of this form is considered a delicacy in the middle east, and is a good source of carbohydrate.

The other widespread identification is that manna is the thalli of certain Lichen (particularly Lecanora esculenta); this food source is often used as a substitute for maize in the steppes of central Asia. This material is light, often drifting in the wind, and has a yellow outer coat with white inside, somewhat matching the biblical description of manna, although it does need additional drying, and is definitely not similar to honey in taste.

A collection of dried Liberty Cap mushrooms.

A number of ethnomycologists such as R. Gordon Wasson, John Marco Allegro and Terence McKenna, have rediscovered that most of characteristics of manna are similar to that of Psilocybe cubensis, namely that such mushrooms are notorious breeding grounds for insects and decompose rapidly. These peculiar fungi which naturally produce a number of molecules which resemble human neurochemicals first appear as small fibres (called mycelium) which resemble hoarfrost. This speculation (also paralleled by Philip K. Dick in the 1982 posthumously published VALIS science fiction trilogy The Transmigration of Timothy Archer) is supported in a wider cultural context when compared with the praise of Haoma in the Rigveda, and Mexican praise of teonanácatl as well as the peyote sacrament of the Native American Church, and the Holy Ayahuasca used in the ritual of the Unaio De Vegital. These theories are viewed by some academics as viewpoints beyond the fringe. In light of the classification of this organism as a scheduled substance in most countries, it is easy to see why so many resist the idea that the Holy Sacrament is a psychoactive (as wine is). Viewed by scholars as most implausible, however, is the hypothesis of Immanuel Velikovsky that manna consisted of hydrocarbon rain resulting from a close encounter between Venus and Earth; this claim has been debunked by Carl Sagan, Stephen Jay Gould, and others.

Other minority identifications of manna are that it was a kosher species of locust, that it was the sap of certain succulent plants (such as those of the genus Alhagi, which have an appetite-suppressing effect), or that it was the miraculous appearance of fully-formed wafers of shewbread. Some people also attribute it to the hemp seed.

Origin

The origin of Manna is clearly in heaven according to the Bible (Psalms 78:24,25, Psalm 105:40 and John 6:31), but the various naturalistic identifications of manna have been compared to things in nature. In the Mishnah manna is treated as a supernatural substance, created during the twilight of the first Friday in existence, and ensured to be clean by the sweeping of the ground by a northern wind, and subsequent rains, before it arrives. According to classical rabbinical literature, manna was ground in a heavenly mill for the use of the righteous, but some of it was allocated to the wicked and left for them to grind themselves.

Use and function

As a natural food substance, the consumption of manna would produce waste products; but in classical rabbinical literature, as a supernatural substance, it was argued that manna produced no waste, resulting in no defecation among the Israelites until several decades later, when the manna had ceased to fall. According to modern medical science, the lack of defecation over such a long period of time would cause extremely severe bowel problems, especially when other food later began to be consumed again; the classical rabbinical writers argue that the Israelites complained about the lack of defecation, and were concerned about potential bowel problems.

According to a number of vegetarian Christians, God had originally intended that man would not eat meat, because (according to these sources) plants cannot move, and therefore killing them wouldn't be sinful; the supply of manna, a non-meat substance, is quoted by these sources as an example of this intention against eating meat. This may perhaps be reinforced in that when the people complained and wished for quail, God gave it to them, and those who ate it grew sick after.

Food wasn't the only use that manna was put to, according to the rabbinical writers; one classical rabbinical source states that the fragrant odour of manna was used as a perfume by the Israelite women.

Gathering

According to the biblical text, each day exactly one omer of manna was gathered per member of each household, regardless of how much effort was put into gathering it; a midrash attributed to Rabbi Tanhuma remarks that although some people were diligent enough to go into the fields to gather manna, lazy individuals just lay down and caught it with their outstretched hands. The Talmud argues that this property was used to solve disputes about the ownership of slaves, since the number of omers of manna each household could gather would indicate how many people were legitimately part of the household; the omers of manna for stolen slaves could only be gathered by the legitimate owner, and therefore the legitimate owner would have a spare omer of manna.

Nevertheless, according to the Talmud, manna was found near to the homes of those with strong belief in Yahweh, and far from the homes of those with doubts; indeed, one classical midrash argues that manna was intangible to non-Jews, as it would inevitably slip from their hands. The Midrash Tanhuma argues that when manna melted, it formed liquid streams that were drunk by a number of animals, flavouring their flesh; this Midrash goes on to argue that some of these animals were subsequently eaten by non-Israelites (implying that such food was also available as an alternative to manna), and it was only in this indirect manner that non-Israelites were able to taste manna. Despite these descriptions of uneven distribution, classical rabbinical literature expresses the view that the manna fell in very large quantities each day, layering over two thousand square cubits, between 50-60 cubits in height; rabbinical literature states that this was enough to nourish the Israelites for 2000 years, and could be seen from the palaces of every king in the East and West, although this improbable statement may be metaphorical.

The Sabbath

The biblical text states that twice as much manna than usual was available on Friday mornings, and none at all could be found on the following day; the text goes on to state that although the manna usually rotted after a single night, the manna which had been collected on Fridays remained fresh for two nights. According to the narrative, the sabbath was instituted at this point, with Moses stating that the extra portion was to be consumed on the sabbath, and Yahweh instructing him that no-one should leave his place on the sabbath, so that the people could rest during it.

Textual scholars regard this part of the manna narrative to be spliced together from the Yahwist and Priestly Source texts, with the Yahwist text being the one emphasising rest during the sabbath, while the Priestly Source merely states that a sabbath exists, implying that the meaning of a sabbath was already known. Biblical scholars regard this part of the manna narrative as an aetiological myth designed to explain the origin of sabbath observance, which in reality was probably pre-Mosaic.

Duration of supply

According to the Book of Exodus, the Israelites consumed the manna for 40 years, but it then ceased to appear once they had reached a settled land; the Book of Exodus also states that the manna ceased to appear once the Israelites reached the borders of Canaan (which was inhabited, by the Canaanites). According to the Book of Joshua, the manna ceased to appear on the day after the annual passover festival, when the Israelites had reached Gilgal. Textual scholars attribute these variations to the fact that each expression, of when the manna ceased, derives from different source texts; the claim that the Israelites ate manna for 40 years, until reaching a settled land, is attributed by textual scholars to the Priestly Source; the reference to Canaan's borders is considered to be either from the Jahwist account, or a later redaction to synchronise the account with that of the book of Joshua. There is also a disagreement among classical rabbinical writers as to when the manna ceased, particularly in regard to whether it remained after the death of Moses for a further 40 days, 70 days, or 14 years; indeed, according to Joshua ben Levi, the manna ceased to appear at the moment that Moses died.

The Pot of Manna

Despite the eventual termination of the supply of manna, the text states that a small amount of it survived within a pot, which was kept adjacent to the Ark of the Covenant; the text indicates that the instruction for this to occur had been given to Moses by Yahweh, and Moses had delegated the task to Aaron. The Epistle to the Hebrews gives a slightly different account, stating that the pot was stored inside the Ark. The classical rabbinical sources give different viewpoints on how long the pot survived, with some arguing that it was only there for the generation following Moses, and others arguing that it survived at least until the time of Jeremiah; textual scholars attribute the mention of the pot to the priestly source, therefore indicating that the pot existed in the early 6th century BC.

Later cultural references

Manna Ash

By extension "manna" has been used to refer to any divine or spiritual nourishment. In a modern botanical context, manna is often used to refer to the secretions of various plants, especially of certain shrubs and trees, and in particular the sugars obtained by evaporating the sap of the Manna Ash, extracted by making small cuts in the bark. The Manna Ash, native to southern Europe and southwest Asia, produces a blue-green sap, which has medicinal value as a mild laxative, demulcent, and weak expectorant.

In the 17th century, a woman manufactured a clear, tasteless, cosmetic product, which she named the Manna of Saint Nicholas of Bari; initially this was very popular, but after the deaths of 600 men, who were married to women using the product, government investigations discovered that the cosmetic was primarily composed of arsenic. In modern times, Roman Catholic authorities annually collect a clear liquid from the tomb of Saint Nicholas; the pleasant perfume of this liquid is argued by Roman Catholic legend to be able to ward off evil, and for this reason it is sold to pilgrims as the Manna of Saint Nicholas. The liquid gradually seeps out of the tomb, but it is unclear whether it originates in the body within the tomb, or from the marble itself; since the town of Bari is a harbour, and the tomb is below sea level, there are several natural explanations for the Manna fluid, including the transfer of seawater to the tomb by capillary action.