Lessico

Johann Günther von Andernach

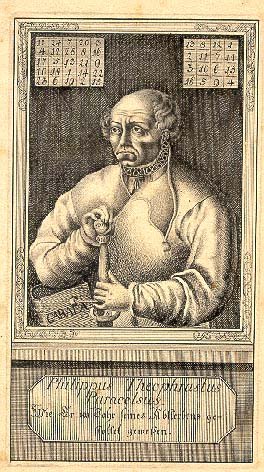

Icones veterum aliquot ac recentium Medicorum

Philosophorumque

Ioannes Sambucus / János Zsámboky![]()

Antverpiae 1574

Medico

tedesco (Andernach 1487? ca. 1505 - Strasburgo 1574). Anatomista della scuola

detta umanista perché più attenta alla rielaborazione di testi che non alla

dissezione, tradusse e studiò Galeno![]() .

Lavorò e insegnò a Parigi, dove fu anche maestro di Andrea Vesalio

.

Lavorò e insegnò a Parigi, dove fu anche maestro di Andrea Vesalio![]() .

La sua opera rappresenta un momento di passaggio tra il pensiero classico

medico greco-latino e il rinascimento scientifico.

.

La sua opera rappresenta un momento di passaggio tra il pensiero classico

medico greco-latino e il rinascimento scientifico.

Aldrovandi ne cita il De medicina veteri et nova tum cognoscenda tum faciunda commentarii duo (Basel, 1571) in cui Günther cercò di unificare la medicina di Galeno con quella di Paracelso, un lavoro dedicato all’imperatore Massimiliano II. Interessante l’ampia e documentata biografia che segue, tratta da www.whonamedit.com.

|

German

physician, born ca. 1505, Andernach; died October 4, 1574, Strassburg,

France. There is a lot of confusion both about the year of birth and

the correct name of this physician. His name is most often given as

Johann Guenther von Andernach. Other spellings being Guintherus

Andernacus, Gonthier d’Andernach, Jean Guinter d’Andernach,

Ioannes Guinterius Andernacus, and Johann Winther von Andernach. The

middle name is also frequently spelled Günther, Guinterus,

Guintherius. His year of birth is frequently erroneously given as

1487. Guinters’

native town was the ancient Roman city of Antunnacum, situated

on the west bank of the Rhine, between present cities of Bonn and

Koblenz in Rheinland-Pfalz (Rhineland-Palatinate). Nothing

is known of Guinter’s family, except that it was obscure and

impoverished, or of his earliest education. The diligent and

sharp-witted boy received his first education at the city school in

Andernach, and is said to have left his native city at the age of

twelve, in quest of learning. Guinter first studied the arts and Greek

at Utrecht, where he became befriended with the Dutch philologist

Lambert Hortensius. Then, supported by his benefactor, Duke Anton von

der Mark, went to Deventer, and Marburg, in which last place he

completed his humanistic and philosophical studies. Guinter

soon earned a reputation for learning, and thus was called to Goslar,

Saxony, as headmaster - rector - of a preparatory school. Here he

recouped his funds and was able to proceed to Louvain (Löwen) for

further study - particularly perfecting his Greek under Rutger Rescius

at the Kollegium Buslidanum (founded 1517), and also teaching of Greek,

and then to Liège (Lüttich). At some undetermined earlier time

Guinter seems to have begun the study of medicine at Leipzig, and

about 1527 he proceeded from Liège to Paris to continue that study.

This may have been due to his dire financial condition. Guinter

received the baccalaureate in medicine on April 18, 1528 after two

witnesses had sworn to the fact of his previous studies at Leipzig. On

June 4, 1530 he was promoted licentiate - Magister - and on

October 29, 1532 received the M.D. degree. The Paris Faculty of

Medicine accepted him as a regent doctor on February 6, 1533, and on

November 7, 1534 he was named one of the two professors of medicine at

a salary of twenty-five livres. As

a part of his academic duties Guinter was responsible for the annual

winter course in human anatomy, and it was inevitable during the

pre-vesalian period that his approach would be Galenic. The procedure

followed was in the medieval pattern, with Guinter lecturing to the

class while a barber or surgeon performed the actual dissection in

order merely to illustrate and confirm Galen’s anatomy. However,

Guinter himself appears occasionally to have dissected, although his

technique left much to be desired. One

of his pupils during the period 1533-1536, the later distinguished

anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), referred to Guinter’s

anatomical instruction in strongly condemnatory terms, even declaring:

«I do not consider him an anatomist, and I should willingly suffer

him to inflict as many cuts upon me as I have seen him attempt on man

or any other animal - except at the dinner table.» Nevertheless, it

is to Guinter’s credit that he did attempt to teach his students

some comparative anatomy and was willing to allow them to gain some

experience by participating in the actual dissection. After

Vesalius had left Paris, one of Guinter’s pupils was Miguel Serveto

(1511-1553), famous for his discovery of the small circulation, and

burned on the stake in Geneva by Calvin as a heretic for his

antitrinitarian teaching. In

Paris luck smiled to Guinter, King François I appointed him one of

his physicians, he was highly esteemed by his colleagues and numerous

patients sought his help. Due to his reputation he was invited by King

Christian III of Denmark to become physician at the Danish court, but

turned the offer down. It

was in conjunction with his anatomical course that he published a

dissection manual, Institutiones anatomicae (Paris, 1536), in

four books, dealing first with the more corruptible internal organs

and then with those less susceptible to putrefaction. Thus the work

followed the form first made popular by Mondino da Luzzi (1316), that

is, the medieval method of dissection material. Guinter acknowledged

the assistance of his student Vesalius in preparation of the work,

probably the dissection and preparation of anatomical specimens.

Although Guinter’s manual, preceded only by those of Mondino and

Berengario da Carpi (1522), contained no genuine anatomical

contributions, it did advocate that anatomy, hitherto considered as

chiefly fit for study by surgeons, was fundamental to the education of

the physician. Guinter

was one of the major Greek scholars of his day, a fact first disclosed

by the publication of his Syntaxis Graeca (Paris, 1527). In

particular he devoted his scholarship to translations of the classical

writers on medicine, and in the Commentaries of the Faculty of

Medicine of Paris, he was recognized as having translated the

larger part of Galen’s writings and all those of Paul of Aegina*.

The considerable bulk of Guinter’s translations is explained by his

method, according to which, as he declared, he translated each day as

much as his secretary could write out from dictation, after which

Guinter edited the version for publication. Because

of the growing pressure of religious orthodoxy in France, Guinter, a

Lutheran, left Paris in 1538 for Metz and after about two years went

to Strassburg, where he was accepted to the Citizen’s guild under

his name of Dr. Andernach and was provided with a chair of Greek

studies at the Gymnasium, which had been established in 1538 by

Johannes Sturm. He was a friend of the Strassburg reformists,

particularly Matthias Zell (1477-1548) and his wife Katharina, and

with Martin Butzer (1491-1551). The latter obtained for him a position

as personal physician to the Pfalsgrafen Wolfgang von Zweibrücken. At

the same time he developed a medical practice. However, intrigues and

conflicts of various kinds, and criticism of his double occupation

compelled him to relinquish his academic position in 1556. During his

time in Strassburg he undertook several journeys to Germany and Italy.

Ferdinand I raised him to the nobility. Although

he continued his studies of the classical Greek physicians, producing

a translation of the writings of Alexander of Tralles in 1549, and a

revised edition in 1556, most of his later publications reflected his

interest as a practicing physician. Guinter’s

book of advice on how to avoid the plague, De victus et medicinae

ratione cum alio tum pestilentiae tempore observanda commentarius

(Strassburg, 1542), was written on the request of the city council of

Strassburg. It was translated into French by Antoine Pierre in 1544 and by Guinter in

1547 as Instruction très utile par laquelle un chacun se pourra

maintenir en santé, tant au temps de peste, comme autre temps. Further

works on this subject were Bericht, regiment, und Ordnung wie die

Pestilenz und die pestilenzialische Fieber zu erkennen und zu kurieren

(Strassburg, 1564) and De pestilentia commentarius in quatuor

dialogos distinctus (Strassburg, 1565). He

wrote a general study of medicine containing some autobiographical

material, De medicina veteri et nova tum cognoscenda tum faciunda

commentarii duo (Basel, 1571), in which he attempted to unite

Galenic medicine with that of Paracelsus. This work was devoted to

emperor Maximillian II.

Paracelso Guinter

was entombed in the church of St. Gallus in Strassburg. Guinter

was an accomplished osteologist and mycologist, although leaning too

much on Galen. Very good are also his descriptions of the female

pelvis and uterus, as well as the vagina. He was definitely one of the

foremost humanistic physicians of his time. Bibliography: Syntaxis

Graeca. Paris,

1527. De

anatomicis administrationibus.9

books of Galen, translated from Greek into Latin. Paris,

1531. Opus

de re medica. Book

of Paul of Aegina. Paris, 1532. Liber

celerum vel acutarum passionum. Book

of Caelius Aurelianus. Paris, 1533. Commentaria

in aphorismos Hippocratis. Book

of Oribasus. Paris,

1533. De

Hippocratis et Platonis placitis. Book

of Galen, translated from Greek into Latin Paris, 1534. Anatomicarum

institutionum, secundum Galeni sententiam, libri quatuor. Paris,

1536; Basel 1536; Venice, 1538; Padua, 1558. This first edition was

published as a manual for medical students, and, although the book

exerted considerable influence at the time, it was essentially Galenic

in tradition and provided little new anatomical knowledge. In the

second edition, probably published in 1540, Vesalius made a number of

changes, and it is evident that Vesalius was beginning to suspect the

errors in Galen, which he later exposed. Also included in this work is

Giorgia Valla’s (1447-1500) De humani corporis partibus.

Valla was an Italian mathematician and physician who practiced in

Milano and Venice. Later in his career he taught at Padua and occupied

a chair of rhetoric at Venice. In addition to his several medical and

mathematical works, he translated a number of Greek scientific texts

into Latin including selections from Aristotle, Hippocrates, Galen,

Rhazes, and Averroës. De

victus ed medicinae ratione cum alio tum pestilentiae tempore

observanda commentarius. Strassburg,

1542. Bericht,

regiment, und Ordnung wie die Pestilenz und die pestilenzialische

Fieber zu erkennen und zu kurieren. Strassburg,

1564. Written on the reequest of the city council of Strassburg. Avis,

Régime et ordonnance pour connaître la peste etc. Strassburg,

1564 and 1610. De

pestilentia commentarius in quatuor dialogos distinctus. Strassburg,

1565. Commentarius

de balneis, & aquis medicatis in tres dialogos distinctus. Strassburg, Excudebat Theodosius Rihelius, 1565; German translation by

Etschenreuter, 1571. In this small book on thermal springs, Guinterius

gives many interesting details on the waters of Baden near Vienna,

Baden-Baden, Ems, Karlsbad, and many other springs around Europe. De

medicina veteri et nova. Basel,

1571. An attempt at unifying Galenic medicine with that of Paracelsus.

Also containing some autobiographical material. Gynaeciorum

commentarius, de gravidarum, parturentium, puerperarum & infantium

cura . . . Accessit elenchus auctorum in re media cluentium, qui

gynaecia scriptis clararunt & illustrarunt. Opera e studio Joan.

Georgii Schenkii . . . Argentorati, Impenzis Lazari Zetzner, 1606. A

work on obstetrics published posthumously by Johann Georg Schenck of

Grafenberg (died 1620). Strassburg, 1606. Schenk wrote the first

bibliography of gynaecology, covering physicians who wrote on the

subject from the earliest times to the beginning of the 17th century.

This was appended to Guenther’s work. The title of Schenk’s

work is Pinax autorum qui gynaecia seu muliebra ex instituto

scriptis exoluerunt et illustrarunt. |