Lessico

Muschio

Muschio

deriva dal latino tardo muscus, che risale al persiano musk,

propriamente mosco. Nome convenzionale usato nell'industria dei profumi per

indicare il caratteristico odore del muschio del Tonchino (regione

storico-geografica dell'Indocina interamente compresa nel Viet Nam di cui

costituisce la sezione settentrionale)

noto da tempi remoti

e ricavato dal secreto della ghiandola prepuziale del mosco![]() - Moschus moschiferus - cervide asiatico. Analogo odore ha il secreto

prodotto da una ghiandola perineale del topo muschiato

- Moschus moschiferus - cervide asiatico. Analogo odore ha il secreto

prodotto da una ghiandola perineale del topo muschiato![]() o rat musqué, Ondatra

zibethica.

o rat musqué, Ondatra

zibethica.

La struttura chimica dei componenti del muschio è quella dei composti

macrociclici ed è analoga a quella di alcuni composti vegetali di odore più

o meno muschiato, come per esempio l'ambrettolide dei semi dell'abelmosco![]() , Abelmoschus

moschatus o Hibiscus abelmoschus. Attualmente, i vari tipi di

muschio e quelli di odore analogo, noti in profumeria con i nomi di esaltone e

di esaltolide, vengono prodotti per sintesi.

, Abelmoschus

moschatus o Hibiscus abelmoschus. Attualmente, i vari tipi di

muschio e quelli di odore analogo, noti in profumeria con i nomi di esaltone e

di esaltolide, vengono prodotti per sintesi.

Un odore di muschio assai meno puro e gradevole presentano i dinitroderivati

della serie aromatica, noti col nome d'uso di muschio chetone e muschio

ambretta, i quali trovano impiego per profumare saponi di non alto pregio.

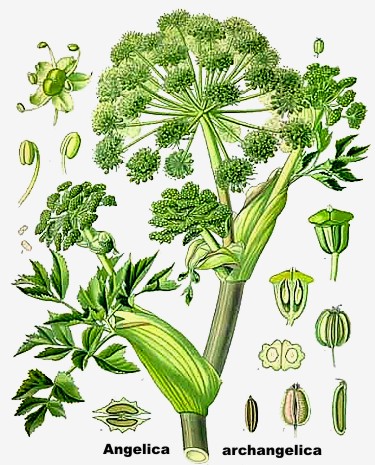

Altra fonte di un profumo più o meno muschiato è rappresentata dall'Angelica

archangelica![]() .

.

Il mosco moschifero, detto anche cervo muschiato, (Moschus moschiferus, Linnaeus 1758) è un ruminante della famiglia dei moschidi diffuso in Siberia, Corea, Manciuria, Mongolia nord-orientale e sull'isola di Sakhalin. È lungo circa 1 m e alto al garrese (situato fra il margine inferiore del collo e il dorso) fino a 55 cm. La colorazione del mantello segue una vasta gamma che può andare dal bruno-giallastro al nero, ma il colore più diffuso è il bruno scuro. Le zampe posteriori sono molto più lunghe delle anteriori, a causa dell'adattamento all'andatura saltellante di questo animale.

La testa è piuttosto piccola rispetto al resto del corpo, ma le caratteristiche facciali (occhi, orecchie) sono molto grandi, dando un effetto comico enfatizzato dai movimenti di questo animale. I canini sono ben sviluppati in entrambi i sessi, ma nel maschio possono superare i 10 cm e sono ben visibili anche quando la bocca è chiusa. Il maschio possiede inoltre una ghiandola che produce una sostanza dal forte odore muschiato, molto ricercata nell'industria del profumo e a causa della quale questi animali sono stati (e vengono tutt'ora) cacciati fin quasi all'estinzione.

I cuccioli nascono fra maggio e giugno e restano nascosti per circa due mesi, con la madre che li vede solo al momento dell'allattamento: circa un terzo delle femmine tende a non riprodursi in un dato anno. È un animale strettamente notturno che vive nella taiga. Percorre circa 6 km ogni notte per trovare il cibo, che consiste in licheni ed erba, ma generalmente all'alba torna sempre nello stesso punto.

Il Muschio del Cashmir

C’e un profumo così famoso che tutti sulla terra ne conoscono il nome, ma è così raro che pochissimi esseri umani possono vantarsi di averlo mai sentito. È il muschio. Il muschio viene da un piccolo cervo del Cashmir con due zanne buffe che gli servono a staccare il muschio di foresta di cui di nutre. Sotto la pancia ha due ghiandole pelose che producono piccole palline di una sostanza nera molto odorosa; il muschio. Soltanto il cervo maschio produce il muschio, e va seminando grani profumati sul suo territorio per avvertire gli altri maschi che questa è casa sua e di non pensare a stabilirsi in questa zona. I grani di muschio servono anche a sedurre una femmina perché tutti sanno che le femmine vanno pazze per i profumi.

Ma anche le femmine degli uomini adorano questo profumo incredibilmente attraente, e da migliaia di anni i maschi usano il muschio per profumarsi così da essere più seducenti. Tanti anni fa, quando Marco Polo viaggiò in Cashmir, il muschio era raccolto una volta l’anno, sul suolo dei boschi, dagli uomini del Re del Kashmir ed era vietato disturbare i cervi. Da quando non c’e più un Re in Cashmir per punire coloro che fanno del male al prezioso animale, i cacciatori li uccidono, poi tagliano le ghiandole per venderli.

I grani di Muschio che sono all'interno delle borse del muschio sono anche un rimedio per malattie molto gravi e vengono usati in tutte le farmacopee dell’antichità. C’è un uomo nella montagna che prepara medicine con il Muschio secondo le ricette trasmesse dagli antenati e ho avuto il privilegio di vedere come è preparato il vero muschio del Cashmir e sopratutto di sentire il suo profumo esilarante. L’odore della "borsetta" ghiandola è dolcissimo, ma quando la si apre per ricavare i grani il profumo è tutto diverso. Al primo impatto il Muschio è fortissimo, anche per un profumiere come me, abituato a lavorare con essenze pure, e non è particolarmente gradevole, sembra ammoniaca, ma è solo perché è fresco e molto concentrato. In effetti 3 piccoli grani di 1 grammo servono per fare un litro di profumo alcolico.

Il migliore modo per capire e apprezzare la delicatezza del profumo di muschio è di annusare la scatola o il vaso che lo contiene mentre sono chiusi, sembra che sia talmente potente da passare attraverso le parete dei recipienti. C’erano lì due clienti che compravano degli ingredienti per fare un rimedio tradizionale. Hanno preso le cose più costose di tutte, l’oro da mangiare in fogli finissimi, il muschio, l’ambra grigia, lo zafferano dall’Iran e le perle di mare. Non ho chiesto per che cosa era il rimedio perché sapevo che questi sono gli ingredienti che usa il marito quando vuole fare piacere a sua moglie.

Purtroppo, a causa della caccia indiscriminata, i cervi muschiati sono quasi tutti morti e forse tra qualche anno non ci sarà più il meraviglioso profumo del muschio da sentire sulla terra. L’avidità degli uomini li spinge a distruggere il proprio commercio con le loro mani, un po’ come un uomo su una barca che sfonda lo scafo con il piccone perché vuole della legna per accendere un fuoco e riscaldarsi. Non capisce che la nave colerà a picco e si ritroverà a nuotare nell’acqua ancora più fredda. Anche i pescatori nel mare si lamentano: “Non c’e più pesce, non guadagniamo più sufficientemente per mantenere le nostre famiglie!”. È chiaro, se pescate troppo pesce, quello che nasce non basta per rimpiazzare quello che avete ucciso.

Lo stesso accade oggi con il muschio, con gli elefanti, con l’albero del profumo di sandalo e con l’albero del profumo di legno di rosa. Ne sono rimasti pochissimi. Per questa ragione è stato vietato il commercio del muschio, ma non serve a nulla perché il cacciatore è povero e vuole portare soldi a casa per la sua famiglia e quindi uccide il piccolo cervo. La soluzione è di fare qualcosa come si fa in Italia con i fagiani; li si alleva in fattorie al riparo dei cacciatori e li si libera poi nella natura. Un'altra soluzione è di dare uno stipendio al cacciatore per proteggere i cervi, così non avrebbe bisogno di soldi e non li ucciderebbe più. Dopo di che si potrà ricominciare la raccolta dei grani nel bosco, dove il cervo li semina, come al tempo di Marco Polo. Ad ogni problema la sua soluzione.

AbdesSalaam

Attar, Cashmir, Marzo 2006

www.profumo.it

The Siberian musk deer (Moschus moschiferus) is a musk deer found in the mountain forests of Northeast Asia. Its is most common in the taiga of southern Siberia, but is also found in parts of Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, Manchuria and the Korean peninsula. It is largely nocturnal, and migrates only over short distances. It prefers altitudes of more than 2600 m. Adults are small, weighing 7-17 kg.

The Siberian musk deer is classified as threatened by the IUCN. It is hunted for its musk gland, which fetches prices as high as $45,000 per kilogram. Only a few tens of grams can be extracted from an adult male. It is possible to remove the gland without killing the deer, but this is seldom done. A distinct subspecies roams the island of Sakhalin.

Moschus moschiferus

Siberian musk deer

Taxonomy

Moschus moschiferus [Linnaeus, 1758].

Citation: Syst. Nat., 10th ed., 1:66.

Type locality: "Tataria versus Chinam"; restricted to Russia, SW Siberia, Altai Mtns by Heptner et al. (1961)

General Characteristics

Body Length: 86-100 cm / 2.8-3.3 ft.

Shoulder Height: 52-55 cm / 20.5-21.5 inches.

Tail Length: 4-6 cm / 1.6-2.4 in.

Weight: 11-18 kg / 24-40 lb.

The overall colouration of animals varies from a light yellowish brown to almost black, although a dark brown is most common. The head is generally lighter. A pair of whitish stripes extends from the chin down the chest to the belly, while a scattering of lighter spots may be present on the back and sides. Young are born intensely spotted on their upper body, with adult colouration reached gradually by 1.5 years of age. The hind legs are much longer and more powerful than the front legs, which causes the back to slope, and is an adaptation to saltatorial (jumping) locomotion. The hindquarters, which are highly arched, may be 5-10 cm / 2-4 inches higher than the shoulders. This feature is further emphasized by the small chest and thin neck which is carried low. The head is elongated and small relative to the body. The features of the face, however, are oversized. The eyes are large and the ears are long and rounded, with have a wide range of mobility. Antlers are not present in this species, however, the sharp upper canines of adult males grow very long (up to 10 cm / 4 inches) and project well below the chin in older individuals (the canines of females are not visible).The tail is very small and is often hidden in the fur on the rump. The lateral hooves (dewclaws) are well developed in this species, and are usually seen in the footprints of standing animals.

Ontogeny and Reproduction

Gestation Period: 6.5 months.

Young per Birth: Often 2, sometimes 1 or 3.

Weaning: At 3-4 months.

Sexual Maturity: 15-17 months.

Life span: 10-14 years, up to 20 years in captivity.

The young are usually born in May and June, after which they are hidden - concealed away from their mother for up to 2 months. Up to one third of the females in a population will not reproduce in a given year.

Ecology and Behavior

Musk deer are primarily active at night, although during this period they alternately feed and rest. While foraging, a musk deer may travel 3-7 km per night, generally returning to the same spot (a "lair") every morning. Well-defined pathways are used, becoming permanent tracks rapidly. These tracks facilitate movement in winter, when loose snow prevents easy access to other areas. When chased, musk deer head for rocky terrain, and will try to either reach an inaccessible crag or a shelter. If neither is available, the animal begins to run in circles. Although they can run exceptionally fast, musk deer tire after only 200-300 meters. When running, musk deer may leap like rabbits, with the hind legs landing in front of the front legs. On level ground, musk deer may jump a distance of up to 5 meters, although 2.5 meters is more common. The main vocalization is a soft hiss. Average population density is about 0.6 animals per square kilometer, although under favourable conditions this may be as high as 4-8.5 animals per square kilometer. Individuals inhabit home ranges between 200 and 300 hectares in size, sticking to the boundaries steadfastly. The size of the home range decreases markedly during the second half of winter. Seasonal migrations are minimal if at all present.

Family group: Generally solitary, sometimes small groups (no more than 3 individuals) of a females with her young.

Diet: Lichens (arboreal and terrestrial), grasses, shoots and branches, leaves, coniferous needles and bark.

Main Predators: Lynx, wolverine, yellow-throated marten, rarely wolf, tiger, and bear.

Distribution

Mountainous taiga (broadleaf and needle forest) throughout the Soviet Union, Korea, northern China, and northern Mongolia.

Conservation Status

The Siberian musk deer is classified as vulnerable by the IUCN (1996).

Remarks

Considered to be the most primitive of the deer, the four species of musk deer have sometimes been placed in their own family, Moschidae, as their morphology is half-way between chevrotains and the true deer. Until fairly recently, all species of musk deer were clumped as subspecies of Moschus moschiferus. The musk produced by these deer is highly held for its cosmetic and alleged pharmaceutical properties, and can fetch U.S. $45,000 per kilogram (2.2 pounds) on the international market. Although this musk, produced in a gland of the males, can be extracted from live animals, most "musk-gatherers" kill the animals to remove the entire sac, which yields only about 25 grams (1/40 of a kilogram) of the brown waxy substance. Moskhos (Greek) musk, also moschus (New Latin) musk.Fero (Latin) I bear, carry, hence moschiferus, a carrier of musk: the male has an abdominal glandular pouch which produces a strongly scented musk.

www.ultimateungulate.com

Musk is the name originally given to a substance with a penetrating odor obtained from a gland of the male musk deer, which is situated between its stomach and genitals. The substance has been used as a popular perfume fixative since ancient times and is one of the most expensive animal products in the world. The name, originated from Sanskrit muská meaning "testicle," has come to encompass a wide variety of substances with somewhat similar odors although many of them are quite different in their chemical structures. They include glandular secretions from animals other than the musk deer, numerous plants emitting similar fragrances, and artificial substances with similar odors.

Until the late 19th century, the natural musk were used extensively in perfumery until economic and ethical reasons motivated the adoption of synthetic musk, which are used almost exclusively. The organic compound primarily responsible for the characteristic odor of musk is muscone. Modern use of natural musk pods is limited to Traditional Chinese medicine.

Musk deer

Musk was unknown in classical antiquity and reference to it does not appear until the 6th century, when the Greek explorer Cosmas Indicopleustes mentioned it as a product obtained from India. Soon afterwards Arab and Byzantine perfume makers began to use it, and it acquired a reputation as an aphrodisiac. Under the Abbasid Empire of Arabs it was highly regarded, and the caliphs of Baghdad used it lavishly. In the early 9th century, Al-Kindi included it in a large number of his perfume recipes and it became one of the important luxury items brought by Arabian ships from the East. The etymology of the name musk, originating from Sanskrit muská via Middle Persian mušk, Late Greek móschos, Late Latin muscus, Middle French musc and Middle English muske, hints at its trade route.

The musk deer Moschus moschiferus belongs to the family Moschidae and lives in Pakistan, India, Tibet, China, Siberia and Mongolia. To obtain the musk, the deer is killed and its gland, also called "musk pod", is removed. It is dried either in the sun, on a hot stone, or by immersion in hot oil. Upon drying, the reddish-brown paste turns into a black granular material called "musk grain", which is used for alcoholic solutions. The aroma of the tincture becomes more intense during storage and gives a pleasant odor only after it is considerably diluted. No other natural substance has such a complex aroma associated with so many contradictory descriptions; however, it is usually described abstractly as animalic, earthy and woody or something akin to the odor of baby's skin.

Good musk is of a dark purplish color, dry, smooth and unctuous to the touch, and bitter in taste. It dissolves in boiling water to the extent of about one-half; alcohol takes up one-third of the substance, and ether and chloroform dissolve still less. The grain of musk will distinctly scent millions of cubic feet of air without any appreciable loss of weight, and its scent is not only more penetrating but more persistent than that of any other known substance. In addition to its odoriferous principle, it contains ammonia, cholesterol, fatty matter, a bitter resinous substance, and other animal principles.

The best quality is Tonkin musk from Tibet and China, followed by Assam and Nepal musk, while Carbadine musk from Russian and Chinese Himalayan regions are considered inferior. Obtaining one kilogram (2.2 lb) of musk grains requires between thirty and fifty deer, making musk tinctures highly expensive. At the beginning of the 19th century, Tonkin musk grains cost about twice their weight in gold.

Musk has been a key constituent in many perfumes since its discovery, being held to give a perfume long-lasting power as a fixative. Despite its high price, musk tinctures were used in perfumery until 1979, when musk deers were protected as an endangered species by the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES). Today the trade quantity of the natural musk is controlled by CITES but illegal poaching and trading continues. An illegal shipment of 700 kilograms (1,500 lb) of Chinese musk from the musk deer was seized in Japan in 1987, an amount corresponding to approximately 100,000 deer killed.

Other animals

Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), a rodent native to North America, has been known since the 17th century to secrete a glandular substance with a musky odor. A chemical means of extracting it was discovered in the 1940s, but it did not prove commercially worthwhile.

Glandular substances with musk-like odor are also obtained from the Musk Duck (Biziura lobata) of southern Australia, the musk shrew, the musk beetle (Aromia moschata), the musk turtle, the alligator of Central America, and from several other animals. In crocodiles, there are two pairs of musk glands, one pair situated at the corner of the jaw and the other pair in the cloaca. Musk glands are also found in snakes.

Plants

Some plants such as Angelica archangelica or Abelmoschus moschatus produce musky smelling macrocyclic lactone compounds. These compounds are widely used in perfumery as substitutes for natural musk or to alter the smell of a mixture of other musks. The plant sources include musk flower (Mimulus moschatus), the muskwood (Olearia argophylla) of the Guianas and West Indies, and the seeds of Abelmoschus moschatus (musk seeds).

Artificial compounds

Most modern musk-scented products consist primarily of synthetic musk. Since obtaining the deer musk requires killing the endangered animal, nearly all musk fragrance used in perfumery today is synthesis, or called "white musk". They can be divided into three major classes — aromatic nitro musks, polycyclic musk compounds, and macrocyclic musk compounds. The first two groups have broad uses in industry ranging from cosmetics to detergents. However, the detection of the first two chemical groups in human and environmental samples as well as their carcinogenic properties initiated a public debate on the use of these compounds and a ban or reduction of their use in many regions of the world. As an alternative, macrocyclic musk compounds are expected to replace them since these compounds appear to be safer.

Nitro-musks

An artificial musk was obtained by Albert Baur in 1888 by condensing toluene with isobutyl bromide in the presence of aluminium chloride, and nitrating the product. It was discovered accidentally as a result of Baur's attempts at producing a more effective form of trinitrotoluene. It appears that the odour depends upon the symmetry of the three nitro groups. Following the discovery of Musk Baur, the first nitro-musk, many similar preparations have been made. Notable nitro-musks include:

Musk Baur (Tonquinol)

Musk Ketone

Musk Xylene

Musk Ambrette

Moskene

Polycyclic musks

An artificial musk that contains more than one ring in its molecular structure. These musks became popular after World War II and slowly supplanted the nitro-musks in popularity due to the latter's toxicity and molecular instability. The creation of this class of musks was largely prompted through the need for eliminating the nitro functional group from nitro-musks due to their photochemical reactivity and their instability in alkaline medium. This shown to be possible through the discovery of Ambral, a non-nitro aromatic musk, which promoted research in the development of nitro-free musks. This lead to the eventual discovery of Phantolide, so named due to its commercialisation by Givaudan without initial knowledge of it chemical structure (elucidated 4 years later). While poorer in smell strength, the performance and stability of this compound class in harsh detergents led to its common use, which spurred further development of other polycyclic musks including Galaxolide.

However it was discovered in the 1990s that polycyclic musks are also potentially harmful in that they can disrupt cellular metabolism. Many of these musks were used in large quantities to scent laundry detergents. Commonly used polycyclic musks include:

Galaxolide

(HHCB)

Tonalide (Musk Plus, AHTN)

Phantolide

Celestolide (Crysolide)

Traesolide

Macrocyclic musks

A class of artificial musk consisting of a single ring composed of more than 6 carbons (often 10-15). Of all artificial musks, these most resemble the primary odoriferous compound from Tonkin musk in its "large ringed" structure. While the macrocyclic musks extracted from plants consists of large ringed lactones, all animal derived macrocyclic musks are ketones. Although muscone, the primary macrocyclic compound of musk was long known, it was only in 1926 where Leopold Ruzicka was able first synthesized this compound in very small quantities. Despite this discovery and the discovery of other pathways for synthesis of macrocyclic musks, compound of this class were not commercially produced and commonly utilized until the late 1990s due to difficulties in their synthesis and consequently higher price.

About half the human population are anosmics (unable to smell) to macrocyclic musks, possibly due to its high molecular weight. Common macrocyclic musks include:

Ethylene Brassilate

Globalide (Habanolide)

Ambrettolide

Muscone

Thibetolide (Exaltolide)

Velvione

Alicyclic musks

Alicyclic musks, otherwise known as cycloakyl ester or linear musks, are relatively novel class of musk compounds. The first compound of this class was introduced 1975 with Cyclomusk, though similar structure were noted earlier in citronellyl oxalate and Rosamusk. Alicyclic musks are dramatically different in structure than previous musks (aromatic, polycyclic, macrocyclic) in that they are modified akyl esters. Although they were discovered more than 10 years before, it was only in 1990 with the discovery and introduction of Helvetolide at Firmenich that a compound of this class was produced at a commercial scale. Romandolide, a more ambrette and less fruity alicyclic musk compared to Helvetolide was introduced ten years later. Common musks of this class include:

Cyclomusk

Helvetolide

Romandolide

Topo

muschiato

Ondatra zibethica

L'ondatra o topo muschiato (Ondatra zibethica) è un roditore appartenente alla famiglia dei Cricetidi. È lunga 30-33 cm, la coda misura 25 cm. La pelliccia è folta, liscia, morbida e lucente, marrone o giallognola sul dorso, più chiara con sfumature rossicce sul ventre, decisamente più scura sulla coda. Ha una corporatura massiccia, una testa corta e larga, un muso grosso e tozzo, il labbro superiore spaccato, le orecchie nascoste nel pelo, la coda piatta ai lati, le zampe posteriori fornite lateralmente di setole facilitanti il nuoto. Tra gli arti posteriori vicino agli organi sessuali si trova una ghiandola grande quasi come una pera che secerne un liquido bianco, oleoso che profuma di zibetto (sostanza secreta dalle ghiandole perineali dei Viverridi) e di muschio.

A prima vista il topo muschiato ricorda un grande topo d'acqua, ma come costumi di vita assomiglia molto di più al castoro. Anch'esso infatti costruisce le tane sulle ripide rive o lungo gli argini dei corsi d'acqua regolati erigendo sulla terraferma dimore sferiche o a cupola. Solo che non fa uso di tronchi d'albero, la dimora infatti è costruita con canne, carice e giunchi cementati col fango, mentre il tetto è costituito da fusti vuoti accatastati gli uni sopra agli altri che permettono l'aerazione. Nella tana dentro la scarpata come nella capanna sulla terraferma troviamo il piccolo bacino, la parte terminale di una lunga galleria che corre per almeno 40 cm sotto la superficie dell'acqua e che può essere raggiunta solo da riva, proprio come avviene per le gallerie dei castori.

A differenza del castoro il topo muschiato nuota essenzialmente con l'ausilio della coda, molto piatta ai lati, agitata con un vivace movimento sinuoso, mentre gli arti posteriori rappresentano solo dei «remi» sussidiari. Il topo muschiato inoltre si serve della coda per produrre, sbattendola con forza nell'acqua, segnali d'allarme acustici in caso di pericolo.

I danni più gravi il topo muschiato non li provoca con le sue incursioni nei silos di patate e di rape, negli orti e nei campi, bensì con i suoi scavi sotterranei lungo gli argini delle peschiere e dei fiumi e nei terrapieni delle ferrovie e delle strade che passano vicine ai corsi d'acqua.

Per indole, in realtà, il topo muschiato è una creatura assolutamente pacifica, socievolissima, tollerante e giocosa, più timida che sfacciata, una creatura che cerca sempre la salvezza nella fuga e si accinge a difendersi solo quando non v'è altra via d'uscita. Non è per nulla intimorito dalla vicinanza dell'uomo, anzi sembra avviarsi a diventare un vero animale «civilizzato». Non è ancora stato dimostrato che in mancanza di sostanze vegetali assalga i granchi, i pesci o gli uccelli acquatici.

La pelliccia del topo muschiato è tenuta in grande pregio da tempo immemorabile e lavorata a visone, a zibellino, a skunk o a otaria orsina. Sempre per la pelliccia il topo muschiato è stato introdotto a suo tempo nello stagno di un parco di un castello presso Praga, in Finlandia e in Russia.

Vive nell'America settentrionale dal Canada al Messico, fu introdotto in Boemia nel 1905, in Finlandia nel 1922, in Russia nel 1929 e si diffuse rapidamente in Austria, Germania, Francia, Svizzera e Jugoslavia.

The muskrat (Ondatra zibethica), the only species in genus Ondatra, is a medium-sized semi-aquatic rodent native to North America, and introduced in parts of Europe, Asia, and South America. The muskrat is found in wetlands and is a very successful animal over a wide range of climates and habitats. It plays an important role in nature and is a resource of food and fur for humans, as well as being an introduced species in much of its present range.

The muskrat is the largest species in the arvicoline subfamily; which includes 142 other species of rodents, mostly voles and lemmings. Muskrats are called "rats" in a general sense because they are medium-sized rodents with an adaptable lifestyle and an omnivorous diet. They are not, however, so-called "true rats", that is members of the genus Rattus.

The muskrat's name comes from the two scent glands which are found near its tail; they give off a strong "musky" odor which the muskrat uses to mark its territory (Caras 1967, Nowak 1983). An archaic name in English for the animal is musquash, derived from the Abenaki native word mòskwas (New Oxford American Dictionary).

An adult muskrat is about 40 to 60 cm (16 to 24 inches) long, almost half of that tail, and weighs from 0.7 to 1.8 kg (1.5 to 4 lb). That is about four times the weight of the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), though an adult muskrat is only slightly longer. Muskrats are much smaller than beavers (Castor canadensis), with whom they often share their habitat. Adult beavers weigh from 14 to 40 kg (30 to 88 lb). The nutria (Myocastor coypus) was introduced to North America from South America in the early twentieth century. It shares the muskrat's habitat but is larger, 5 to 10 kg (11 to 22 lb) and its tail is round, not flattened. It cannot endure as cold a climate as can the muskrat and beaver, and so has spread only in the southern part of their ranges in North America (Caras 1967, Nowak 1983).

Muskrats are covered with short, thick fur which is medium to dark brown in color with the belly a bit lighter. The fur has two layers, which helps protect them from the cold water. They have long tails which are covered with scales rather than hair and are flattened vertically to aid them in swimming. When they walk on land the tail drags on the ground, which makes their tracks easy to recognize (Caras 1967, Nowak 1983).

Muskrats spend much of their time in the water and are well suited for their semi-aquatic life, both in and out of water. Muskrats can swim under water for up to 15 minutes. Their bodies, like those of seals and whales, are less sensitive to the build up of carbon dioxide than those of most other mammals. They can close off their ears to keep the water out. Their hind feet are semi-webbed, although in swimming the tail is their main means of propulsion (Voelker 1986).

Muskrats are found over most of Canada and the United States and a small part of northern Mexico. They always inhabit wetlands, areas in or near salt and fresh-water marshlands, rivers, lakes, or ponds. They are not found in the state of Florida where the round-tailed muskrat, or Florida water rat, (Neofiber alleni) takes their place (Caras 1967).

Muskrats continue to thrive in most of their native habitat and in areas where they have been introduced. While much wetland habitat has been eliminated due to human activity, new muskrat habitat has been created by the construction of canals or irrigation channels and the muskrat remains common and wide-spread. They are able to live alongside streams which contain the sulfurous water that drains away from coal mines. Fish and frogs perish in such streams, yet muskrats may thrive and occupy the wetlands. Muskrats also benefit from human persecution of some of their predators (Nowak 1983).

Muskrats normally live in family groups consisting of a male and female pair and their young. During the spring they often fight with other muskrats over territory and potential mates. Many are injured or killed in these fights. Muskrat families build nests to protect themselves and the young from cold and predators. Extensive burrow systems are dug in the ground adjacent to the water with an underwater entrance. In marshes, lodges are constructed from vegetation and mud. In snowy areas they keep the openings to their lodges open by plugging them with vegetation which they replace every day. Most muskrat lodges are swept away in spring floods and have to be replaced each year. Muskrats also build feeding platforms in wetlands. It is common to find muskrats living in beaver lodges, too. Muskrats help maintain open areas in marshes, which helps to provide habitat for aquatic birds (Nowak 1983, Attenborough 2002, MU 2007).

Muskrats are most active at night or near dawn and dusk. They feed on cattails and other aquatic vegetation. They do not store food for the winter, but sometimes eat the insides of their lodges or steal food that beavers have stored. Plant materials make up about 95 percent of their diets, but they also eat small animals such as freshwater mussels, frogs, crayfish, fish, and small turtles (Caras 1967, Nowak 1983).

Muskrats provide an important food resource for many other animals including mink, foxes, coyotes, wolves, lynx, bears, eagles, snakes, alligators, and large owls and hawks. Otters, snapping turtles, and large fish such as pike prey on baby muskrats. Caribou and elk sometimes feed on the vegetation which makes up muskrat lodges during the winter when other food is scarce for them (MU 2007).

Muskrats, like most rodents, are prolific breeders. Females can have 2 to 3 litters a year of 6 to 8 young each. The babies are born small and hairless and weigh only about 22 grams (0.8 oz). In southern environments young muskrats mature in 6 months, while in colder northern environments it takes about a year. Muskrat populations appear to go through a regular pattern of rise and dramatic decline spread over a 6 to 10 year period. Some other rodents, including famously the muskrat's close relatives the lemmings, go through the same type of population changes (MU 2007).

History and use by humans

Native Americans have long considered the muskrat to be a very important animal. In several Native American creation myths it is the muskrat who dives to the bottom of the primordial sea to bring up the mud from which the earth is created, after other animals had failed in the task (Musgrave 2007, MU 2007).

Muskrats have sometimes been a food resource for humans. Muskrat meat is said to taste like rabbit or duck. In the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Detroit, there is a longstanding dispensation allowing Catholics to consume muskrat on Ash Wednesday and the Fridays of Lent (when the eating of meat, except for fish, is prohibited): because the muskrat lives in water, it is considered equivalent to fish (Lukowski 2007).

Lenten dinners serving muskrat are traditional in parts of Michigan. The meat is also commonly consumed in Belgium and The Netherlands, and is traditional dish on the Delmarva Peninsula and in certain other areas and population segments of the United States.

Muskrat fur is very warm and of good quality, and the trapping of muskrats for their fur became an important industry in the early Twentieth Century, especially in the state of Louisiana. At that time muskrats were introduced to Europe as a fur resource. Muskrat fur was specially trimmed and dyed and called "hudson seal" fur, and sold widely in the United States in the early twentieth century (Ciardi 1983). They spread throughout northern Europe and Asia. Some European countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands consider the muskrat to be a pest that must be exterminated. Therefore the animal is trapped and hunted to keep the population down. The muskrat is considered a pest because its burrowing causes damage to the dikes and levees that these low-lying countries depend on for protection from flooding. Muskrats also sometimes eat corn and other farm and garden crops (Nowak 1983).

Abelmosco

Abelmoschus moschatus

L'abelmosco (Abelmoschus moschatus) è una piccola pianta delle Malvacee spontanea in India e coltivata in Egitto, Giava, nelle Antille e in altri paesi tropicali. In precedenza era assegnata al genere Hibiscus. È particolarmente sfruttata per i suoi semi impiegati per aromatizzare (come ad esempio per l'Acquavite di Danzica) e da cui si estrae un olio (ambretta) impiegato in profumeria. Il fusto dell'abelmosco e di altre Malvacee, convenientemente macerato, fornisce una fibra tessile chiamata fibra di gombo.

I semi di abelmosco sono noti anche come semi di ambretta, semi di ambra, semi o grani muschiati. Hanno un aspetto reniforme appiattito, sono lunghi 4 mm e spessi 3 mm, di colore dal bruno grigiastro al verdognolo e striati. I semi, intensamente profumati di muschio, vengono impiegati industrialmente e sono suddivisi in base alla provenienza. I migliori sono considerati quelli della Martinica mentre quelli indiani sono spesso mescolati con semi di trigonella o dell'Abutilon indicum.

Abelmoschus moschatus (Ambrette seeds, Annual hibiscus, Bamia Moschata, Galu Gasturi, Muskdana, Musk mallow, Musk okra, Musk seeds, Ornamental okra, Rose mallow seeds, Tropical jewel hibiscus, Yorka okra; syn. Hibiscus abelmoschus L.) is an aromatic and medicinal plant in the Malvaceae family, which is native to India. The seeds have a sweet, flowery, heavy fragrance similar to that of musk. Despite its tropical origin the plant is frost hardy.

Musk mallow oil was once used as a substitute for animal musk; however this use is now mostly discontinued as it can cause photosensitivity. It has many culinary uses. The seeds are added to coffee; unripe pods ("musk okra"), leaves and new shoots are eaten as vegetables. Different parts of the plant have uses in traditional and complementary medicine, not all of which have been scientifically proven. It is used externally to relieve spasms of the digestive tract, cramp, poor circulation and aching joints. It is also considered an insecticide and an aphrodisiac. In industry the root mucilage provides sizing for paper; tobacco is sometimes flavoured with the flowers.

Angelica

Angelica archangelica

L'angelica (Angelica archangelica L.) è una pianta biennale della famiglia delle Apiaceae (Ombrellifere). L'aspetto è quello classico della famiglia delle ombrellifere principali (finocchio, sedano, prezzemolo ecc.). I gambi sono utilizzati in pasticceria e confetteria come di frutta candita. Le parti tenere possono essere usate come condimento per aromatizzare insalate o minestre. I semi e i gambi possono venire impiegati nella preparazione di liquori.

Viene usata in erboristeria che ne utilizza le radici, le foglie e i semi, però i maggiori trattati ne limitano l'assunzione e consigliano l'uso dietro consulto medico perché ad alte dosi la pianta è velenosa e fotosensibilizzante e ne vietano l'uso in gravidanza e allattamento.

La radice di angelica è un tonico eccellente dello stato generale, e può venire usata contro la stanchezza e l'astenia. L'angelica si rivela inoltre essere un buon stimolante dell'apparato digestivo. È indicata in caso di dolori e spasmi intestinali, dispepsia, gas intestinali.

La somiglianza con le altre ombrellifere, tra cui la velenosa Cicuta impone una certa attenzione nella raccolta. La Cicuta emana uno sgradevole odore di urina, e le foglie, sono molto più simili al prezzemolo.

Garden Angelica (Angelica archangelica; syn. Archangelica officinalis Hoffm., Archangelica officinalis var. himalaica C.B.Clarke) is a biennial plant from the umbelliferous family Apiaceae. Alternative English names are Holy Ghost, Wild Celery, and Norwegian angelica During its first year it only grows leaves, but during its second year its fluted stem can reach a height of two meters (or six feet). Its leaves are composed of numerous small leaflets, divided into three principal groups, each of which is again subdivided into three lesser groups. The edges of the leaflets are finely toothed or serrated. The flowers, which blossom in July, are small and numerous, yellowish or greenish in colour, are grouped into large, globular umbels, which bear pale yellow, oblong fruits. Angelica only grows in damp soil, preferably near rivers or deposits of water. Not to be confused with the toxic Pastinaca sativa, or Wild Parsnip.

Angelica archangelica grows wild in Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Greenland, the Faroe Islands and Iceland, mostly in the northern parts of the countries. It is cultivated in France, mainly in the Marais Poitevin, a marsh region close to Niort in the départment Deux-Sèvres.

Usage - History

From the 10th century on, angelica was cultivated as a vegetable and medicinal plant, and achieved great popularity in Scandinavia in the 12th century and is still used today, especially in Sami culture. A flute-like instrument with a clarinet-like sound can be made of its hollow stem, probably as a toy for children. Linnaeus reported that Sami peoples used it in reindeer milk, as it is often used as a flavoring agent.

In 1602, angelica was introduced in Niort, which had just been ravaged by the plague, and it has been popular there ever since. It is used to flavour liqueurs or aquavits (e.g. Chartreuse, Bénédictine, Vermouth and Dubonnet), omelettes and trout, and as jam. The long bright green stems are also candied and used as decoration.

Angelica is unique amongst the Umbelliferae for its pervading aromatic odour, a pleasant perfume entirely different from Fennel, Parsley, Anise, Caraway or Chervil. One old writer compares it to Musk, others liken it to Juniper. Even the roots are fragrant, and form one of the principal aromatics of European growth - the other parts of the plant have the same flavour, but their active principles are considered more perishable.

Angelica contains a variety of chemicals which have been shown to have medicinal properties. Chewing on angelica or drinking tea brewed from it will cause local anaesthesia, but it will heighten the consumer's immune system. It has been shown to be effective against various bacteria, fungal infections and even viral infections.

The essential oil of the roots of Angelica archangelica contains ß-terebangelene, C10H16, and other terpenes; the oil of the seeds also contains ß-terebangelene, together with methylethylacetic acid and hydroxymyristic acid.

Angelica seeds and angelica roots are sometimes used in making absinthe. A seeds of a Persian spice plant known as Golpar (Heracleum persicum) are often erroneously labeled as "angelica seeds." True angelica seeds are rarely available from spice dealers.

Etymology

Archangelica comes from the Greek word "arkhangelos" (=arch-angel), due to the myth that it was the angel Gabriel who told of its use as medicine. In Finnish it is called väinönputki, in Sami fádnu, boska and rássi, in English garden angelica, in German Arznei-engelwurz, in Dutch grote engelwortel, in Persian gol-par, in Swedish kvanne, in Norwegian kvann, in Danish kvan and in Icelandic it has the name hvönn.