Lessico

San Pacomio

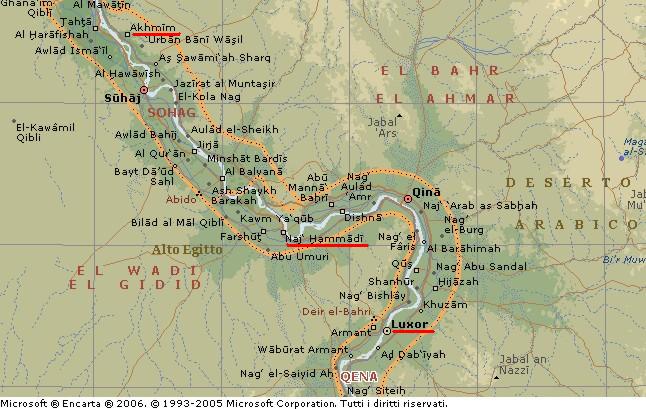

Nato nella Tebaide inferiore ca. 290 – morto a Pebu presso Tebe nel 346. La Tebaide è una regione dell'antico Egitto, con capitale Tebe, corrispondente alla zona a nord dell'odierna Assuan (Aswân).

Pagano, si convertì al cristianesimo abbandonando la vita del soldato. Si ritirò allora a vita eremitica sotto la guida dell'anacoreta Palamone; optò in seguito per la vita comunitaria e istituì un primo cenobio sul Nilo a Tabennisi, cui ne seguirono altri nella regione. Fu il primo a dare ai monaci una regola e un superiore. Fondamento ascetico del cenobio era la preghiera, cui si affiancava una pratica moderata della penitenza. Completava l'attività dei cenobiti il lavoro manuale per il mantenimento proprio e dei poveri. La Chiesa cattolica ne celebra la memoria liturgica il 9 maggio, quella ortodossa il 15 maggio.

Da Adolf Holl, Lo Spirito Santo, Rizzoli, 1998, pagg. 109-110: Uno di costoro, di nome Palamone, viveva nell’Alto Egitto, a un giorno di marcia dalla Valle dei Re, nei pressi dell’attuale Nag Hammadi, e non si rallegrò per niente quando un giorno un colpo alla sua porta disturbò la sua quiete. Il giovane che infine lo persuase a insegnargli la giusta regola di vita si chiamava Pacomio e rimase colà sette anni. Quando il vecchio eremita morì, Pacomio ubbidì alla voce oltremondana che gli aveva ordinato di costruire un monastero ai confini del mondo abitato. Lo sforzo di eliminare il problema dell’esistenza non doveva più, da quel momento, avvenire isolato, ma in istituti chiusi, secondo regole precise e sotto il comando di un Superiore la cui autorità non ammetteva obiezioni.

Tra l’odierna Al-Uqsur (Luxor) e Akhmim, che si trova 180 chilometri più a valle sul Nilo, Pacomio organizzò nel corso di 25 anni nove complessi monastici per uomini e due per donne, con ii centro a Nag Hammadi, secondo un piano dettagliato che non lasciò nulla al caso e che inseriva la persona in una severa geometria dell’ordine spaziale, con unità separate per il sonno, il lavoro e la preghiera. Ogni monastero poteva contenere 1440 persone, suddivise in dieci associazioni di 144 ciascuna, vale a dire quattro laboratori per ogni 36, questi ultimi divisi in dodici celle per dormire, ognuna di tre persone. I laboratori erano specializzati in diversi lavori artigianali e stavano agli ordini di un maestro, che a sua volta rispondeva all’abate, come la maestra alla badessa. Solo i superiori conoscevano il codice, composto dalle 24 lettere dell’alfabeto greco, che registrava ogni monaco e ogni monaca secondo note personali, come una sorta di raffinato sistema di valutazione.

Infatti la vitalità e l’ostinazione sono dure da spezzare, come Pacomio sapeva per esperienza. Donne nude continuavano a emergere dal nulla davanti a lui, giovani e vivaci, proprio all’ora dei pasti. Bisognava chiudere gli occhi davanti a esse, fino a che non svanivano nuovamente nell’aria. Di colpo capitava di percepire la calca di un grande numero di persone, e la voce che diceva: fate posto all’incomparabile uomo di Dio. I fantasmi cercavano anche di suscitare il riso dei fondatori dei monasteri, sforzandosi con ogni sorta di smorfia di spostare un ramo di palma, come se avessero a che fare con pesanti blocchi di pietra.

Un monaco che ride è perduto, decretò Pacomio, il silenzio è oro. Si poteva dormire solo seduti, appoggiati al muro, e non più di tre o quattro ore. Era severamente proibito ogni contatto corporeo tra i consacrati, poiché sotto la tonaca la carne era pronta a reagire alla più leggera stimolazione.

Non era al contrario proibita la lettura di testi edificanti, il cui contenuto corrispondeva, come il ritrovamento di Nag Hammadi ci mostra, all’inclinazione eterodossa del Vecchio di Efeso e anche a quella di Mani. Gente che non ha dormito abbastanza ed è perennemente tormentata dai morsi della fame ha ben poche ragioni di osservare il mondo con occhi allegri.

I fellahin, ai quali i monaci vendevano le proprie ceste e corde, avevano ugualmente ben poco da ridere. Le loro razioni quotidiane di cibo non differivano di molto da quelle dei monaci. Inoltre, con la loro forza lavoro dovevano mantenere moglie e figli, e i capricci del Nilo portavano tanta carestia che dovevano mangiare la carne di sciacallo. I monasteri, invece, potevano permettersi un certo storaggio di scorte, e il lavoro nei loro campi non era decima per proprietari terrieri spietati, ma servizio per la comunità. Le caserme spirituali di Pacomio non avevano alcun problema di reclutamento.

Saint Pachomius (ca. 292-348), also known as Abba Pachomius and Pakhom, is generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism. His saint day is celebrated on 9 May.

He was born in 292 in Thebes (Luxor, Egypt) to pagan parents. According to his hagiography, he was swept up against his will in a Roman army recruitment drive at the age of 20, a common occurrence during the turmoils and civil wars of the period, and held in captivity. It was here that local Christians would daily bring food and comforts to the inmates, which made a lasting impression on him, and he vowed to investigate Christianity further when he got out. As fate would have it, he was able to get out of the army without ever having to fight, was converted and baptised (314). He then came into contact with a number of well known ascetics and decided to pursue that path. He sought out the hermit Palaemon and came to be his follower (317).

Pachomius set out to lead the life of a hermit near St. Anthony![]() of Egypt, whose practices he imitated. An earlier ascetic named Macarius

(ca. 300 - ca. 390) had earlier created a number of proto-monasteries called

"larves", or cells, where holy men would live in a community setting

who were physically or mentally unable to achieve the rigors of Anthony's

solitary life. Pachomius set about organizing these cells into a formal

organization.

of Egypt, whose practices he imitated. An earlier ascetic named Macarius

(ca. 300 - ca. 390) had earlier created a number of proto-monasteries called

"larves", or cells, where holy men would live in a community setting

who were physically or mentally unable to achieve the rigors of Anthony's

solitary life. Pachomius set about organizing these cells into a formal

organization.

Up to this point in time, Christian asceticism had been solitary or eremitic. Male or female monastics lived in individual huts or caves and met only for occasional worship services. Pachomius seems to have created the community or coenobitic organization, in which male or female monastics lived together and had their possessions in common under the leadership of an abbot or abbess. Pachomius himself was hailed as "Abba" (father) which is where we get the word Abbot from. This first coenobitic monastery was in Tabennisi, Egypt.

He established his first monastery between 318 and 323. The first to join him was his elder brother John, and soon more than 100 monks lived at his monastery. He came to build six or seven more monasteries and a nunnery, and after 336, Pachomius spent most of his time at his Pabau monastery. From his initial monastery, demand quickly grew and, by the time of his death in 345, one count estimates there were 3000 monasteries dotting Egypt from north to south. Within a generation after his death, this number grew to 7000 and then moved out of Egypt into Palestine and the Judea Desert, Syria, North Africa and eventually Western Europe.

He is also credited with being the first Christian to use and recommend use of a prayer rope. He was visited once by Basil of Caesarea who took many of his ideas and implemented them in Caesarea, where Basil also made some adaptations that became the ascetic rule, or Ascetica, the rule still used today by the Eastern Orthodox Church, and comparable to that of the Rule of St. Benedict in the West.

Though Pachomius sometimes acted as lector for nearby shepherds, neither he or any of his monks became priests. St Athanasius visited and wished to ordain him in 333, but Pachomius fled from him. Athanasius' visit was probably a result of Pachomius' zealous defence of orthodoxy against Arianism.

He remained abbot to the coenobites for some forty years. When he caught an epidemic disease (probably plague), he called the monks, strengthened their faith, and appointed his successor. He then departed on 14 Pashons, 64 A.M. (9 May 348 A.D.) His reputation as a holy man has endured. He is currently commemorated in several liturgical calendars, including that of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

Examples of purely Coptic literature are the works of Abba Antonius and Abba Pachomius, who spoke only Coptic, and the sermons and preachings of Abba Shenouda, who chose to write only in Coptic. Abba Shenouda was a popular leader who only spoke to the Copts in Coptic, the language of the repressed, not in Greek, the language of the repressive ruler. The Pachomian system tended to treat religious literature as mere written instructions.

The earliest original writings in Coptic language were the letters by St. Anthony of Egypt, first of the “Desert Fathers.” During the 3rd and 4th centuries many ecclesiastics and monks wrote in Coptic, among them, St. Pachomius, whose monastic rule (the first coenobitic rule, for solitary monks gathered in communities) survives only in Coptic. St. Athanasius, is the first Patriarch of Alexandria to use Coptic, as well as Greek.