Principles

and practice of poultry culture – 1912

John Henry Robinson (1863-1935)

Principi

e pratica di pollicoltura – 1912

di John Henry Robinson (1863-1935)

Trascrizione e traduzione di Elio Corti![]()

2016

Traduzione assai difficile - spesso incomprensibile

{} cancellazione – <>

aggiunta oppure correzione

CAPITOLO IX

|

[102] CHAPTER IX |

CAPITOLO IX |

|||

|

COOPS AND BUILDINGS FOR POULTRY |

POLLAI E FABBRICATI PER POLLAME |

|||

|

|

||||

|

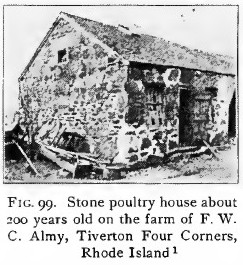

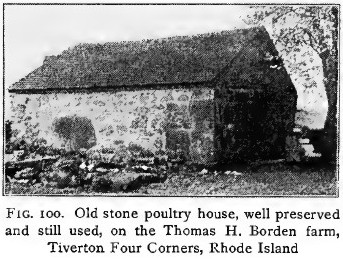

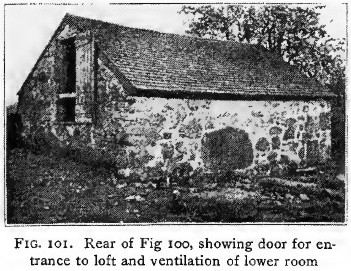

* This is the type of poultry house built by the early settlers in Rhode Island. The houses shown in this and the two following illustrations are supposed to have been built in the latter part of the seventeenth or early in the eighteenth century, and to have been used continuously for poultry ever since. As originally constructed, the ground floors were several feet below the outside ground level, but in both of these houses the floors have been filled in. Access to the loft in the Almy house is by inside stairway. The loft in the Borden house is entered direct from outside, as shown in Fig. 101. It is said that before the colony system came into use, nearly every farm in this district had one of these houses. A few remain in a good state of preservation, but most have fallen into decay. |

* Questo è il tipo di casa per pollame costruito dai primi coloni in Rhode Island. Le case mostrate in questa e nelle 2 successive illustrazioni si suppone siano state costruite nella seconda metà del 17° o all’inizio del 18° secolo, ed essere state usate in continuazione sin da allora per il pollame. Come costruite originariamente, i pianterreni erano molti piedi al di sotto del livello del suolo esterno, ma in ambedue queste case i pavimenti sono stati riempiti. L’accesso alla soffitta nella casa di Almy avviene dalla scala interna. Nella soffitta della casa di Borden si entra direttamente da fuori, come mostra la fig. 101. Si dice che prima che il sistema colonia entrasse in uso, quasi ogni fattoria in questo distretto aveva una di queste case. Alcune rimangono in un buono stato di conservazione, ma la maggior parte è andata in decadimento. |

|||

|

Poultry architecture in general is conspicuous for endless, and often meaningless, variety in proportions and details. This variety extends to every form of structure for every purpose. From the fact that, provided a few simple rules are observed and other factors properly handled, equally good results may be secured in coops and houses differing in many details, such variety is inevitable. But variety is enormously increased because of the number of inexperienced builders who incorporate into the plans that they use untested ideas of their own. The features thus produced are sometimes objectionable, sometimes merely superfluous, rarely of any value, though some such features have at times been widely imitated because of their supposed relation to good results secured or claimed. In the treatment of the subject in this chapter, discussion of the various styles of structures required for different kinds of poultry, for different branches of the work, and for breeds at different stages of growth will be limited to the more representative styles illustrating the evolution [103] of ideas of poultry housing, the principles now best established, and the range within which variations from approved plans may be made without disadvantage. This mode of treatment presents substantially every general design and significant feature that has at any time within the last seventy years been extensively used or seriously considered by experienced poultrymen. |

L’architettura per il pollame è in generale notevole per avere una varietà senza fine, e spesso insignificante, in proporzioni e dettagli. Questa varietà si estende in ogni forma di struttura per ogni scopo. Per il fatto che, purché alcune semplici regole siano osservate e gli altri fattori opportunamente gestiti, buoni esiti possono essere ugualmente assicurati in pollai e case che differiscono in molti dettagli, tale varietà è inevitabile. Ma la varietà è enormemente aumentata a causa del numero di costruttori inesperti che nei progetti che usano incorporano idee non sperimentate da loro stessi. Le caratteristiche così prodotte sono talora deplorevoli, talora soltanto superflue, raramente di qualche valore, sebbene alcune di tali caratteristiche sono state talora estesamente imitate a causa della loro supposta relazione con buoni risultati assicurati o pretesi. Nel trattamento dell’argomento in questo capitolo, la discussione dei vari stili di strutture richieste per tipi differenti di pollame, per rami diversi del lavoro e per razze in diversi stadi di crescita, sarà limitata agli stili più rappresentativi che illustrano l'evoluzione delle idee di albergare il pollame, i principi ora meglio stabiliti, e il campo entro il quale variazioni da piani approvati possono essere fatte senza svantaggio. Questa maniera di trattamento presenta sostanzialmente ogni disegno generale e caratteristica significativa che negli ultimi 70 anni è stata in ogni tempo usata estesamente o seriamente considerata da avicoltori esperti. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

Prime considerations in shelters for poultry. In building shelters for poultry there are three prime considerations: the comfort of the birds, the convenience of the caretaker, and the cost. These items are not always in accord. A building or coop that is comfortable for its small feathered occupants may be very inconvenient for the person who takes care of them, and structures planned with special reference to the convenience of the attendant do not, as a rule, furnish the most satisfactory conditions for the poultry kept in them. Neither the comfort of the birds nor the convenience of the attendant is necessarily proportionate to cost of construction. On the contrary, elaborate plans and expensive construction often mean more work for the poultryman and the least favorable conditions for the poultry. In planning a structure for any purpose the problem is to secure the best adjustment of these three things. |

Le principali considerazioni in ricoveri per pollame . Nel costruire ricoveri per pollame ci sono 3 principali considerazioni: il conforto degli uccelli, la convenienza del custode e il costo. Questi articoli non sono sempre in accordo. Un edificio o stia che è comoda per i suoi piccoli occupanti pennuti può essere molto fastidiosa per la persona che si prende cura di loro, e strutture progettate con speciale riferimento alla convenienza del guardiano non fornisce, come regola, le condizioni più soddisfacenti per il pollame tenuto in esse. Né il conforto degli uccelli né la convenienza del guardiano è necessariamente proporzionata al costo di costruzione. Al contrario, progetti elaborati e costruzione costosa spesso significano più lavoro per l’avicoltore e minime condizioni favorevoli per il pollame. Nel progettare una struttura per ogni scopo il problema è assicurare la migliore messa a punto di queste tre cose. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

[104] Principal requirements in comfortable shelters for poultry. Poultry require fresh air, sunlight, dryness, and room. Of these by far the most important is fresh air. The essential condition of dryness depends much upon free circulation of fresh air. Air and sunlight are nature's best disinfectants and germicides, and if a coop or house is not overcrowded, and the birds are in normal, healthy condition, a properly aired and sunned structure requires much less attention to cleanliness than one that is deficient in these particulars. |

Requisiti principali dei ricoveri accoglienti per il pollame . Il pollame richiede aria fresca, luce del sole, siccità e spazio. Di questi il più importante è di gran lunga l’aria fresca. La condizione essenziale della siccità dipende molto dalla libera circolazione di aria fresca. Aria e luce del sole sono i migliori disinfettanti e germicidi naturali, e se un pollaio o casa non sono sovraffollati, e gli uccelli sono in una condizione normale e sana, una struttura ben aerata e soleggiata richiede molta meno attenzione per la pulizia rispetto a una che non ha questi dettagli. |

|||

|

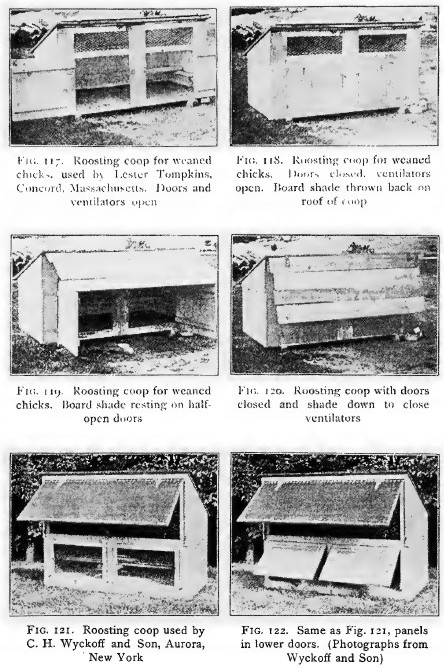

Warmth is not a requisite in a house for birds which are well-feathered, healthy, and have no tender appendages , as large combs and wattles. For unfeathered young birds the quarters must be heated artificially, or so arranged that the heat thrown off by the birds, supplementing the heat of their bodies, will keep the temperature high enough to prevent chilling, while fresh air is still admitted in sufficient quantities. The latter requirement is the theory on which all so-called warm houses have been constructed. The point to be noted is that the unfeathered birds must have warmth, while the more mature stock does not require it. All these points will come out more clearly as the history of modern ideas in construction is briefly sketched in succeeding paragraphs. |

Il calore non è una necessità in una casa per uccelli che sono ben impiumati, sani, e non hanno alcuna appendice delicata , come grandi creste e bargigli. Per i giovani uccelli non impiumati gli alloggi devono essere riscaldati artificialmente, o sistemati in modo tale che il calore eliminato dagli uccelli, completando il calore dei loro corpi, manterrà la temperatura alta abbastanza da prevenire il raffreddamento mentre aria fresca è ancora immessa in sufficienti quantità. Il secondo requisito è la teoria in base alla quale sono state costruite tutte le cosidette case calde. Il punto da tenere presente è che gli uccelli non impiumati devono avere del calore, mentre il gruppo più maturo non lo richiede. Tutti questi punti saranno più chiari dato che la storia delle idee moderne circa la costruzione è brevemente abbozzata nei paragrafi successivi. |

|||

|

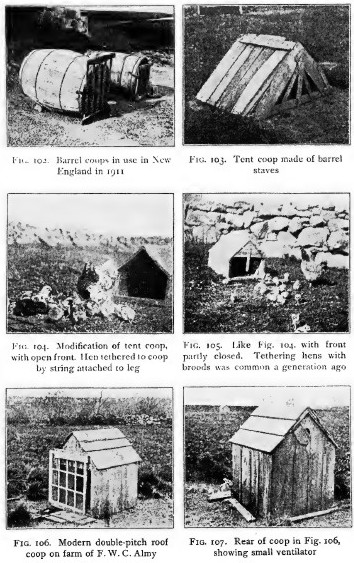

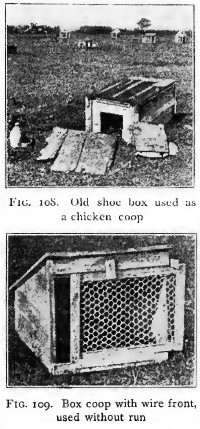

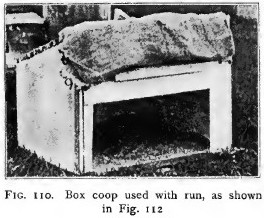

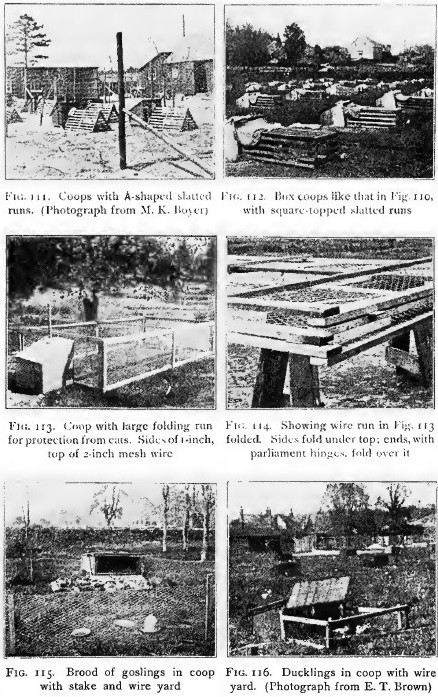

Earliest form of shelter for poultry. An empty barrel (coop), still often used and recommended for a hen and brood, or for a nest for large birds (as the turkey and goose), was in all probability the first form of poultry shelter. Aside from the interesting fact that the adaptation of barrels to such uses gave us the name now used for a small shelter or inclosure, especially for poultry, the early and continued use of the barrel to shelter poultry has peculiar significance to the student of the subject because, though a makeshift with some features which would not be reproduced in a structure designed for poultry, the barrel placed on its side presents in a primitive way what are now recognized as the first principles in poultry-house construction: sufficient shelter, perfect ventilation, and height appropriate to the size of the creatures which are to inhabit it. The use of the barrel is necessarily limited to a few purposes and a small number of individuals. |

La più antica forma di ricovero per pollame . Un barile vuoto (stia), ancora spesso usato e raccomandato per una gallina e per covare, o per un nido per grandi uccelli (come tacchino e oca), era con ogni probabilità la prima forma di ricovero per pollame. A parte il fatto interessante che l'adattamento di barili a tali usi ci ha dato il nome ora usato per un piccolo ricovero o recinzione, specialmente per il pollame, l’antico e continuo uso del barile per ricoverare pollame ha un particolare significato per lo studente dell’argomento perché, sebbene un ripiego con alcune caratteristiche che non sarebbero riprodotte in una struttura ideata per il pollame, il barile messo sul suo lato presenta in un modo primitivo quello che ora sono riconosciuti come i primi principi nella costruzione di una casa per pollame: ricovero sufficiente, ventilazione perfetta e altezza adatta alla taglia delle creature che debbono abitarlo. L'uso del barile è necessariamente limitato a pochi scopi e a un piccolo numero di individui. |

|||

|

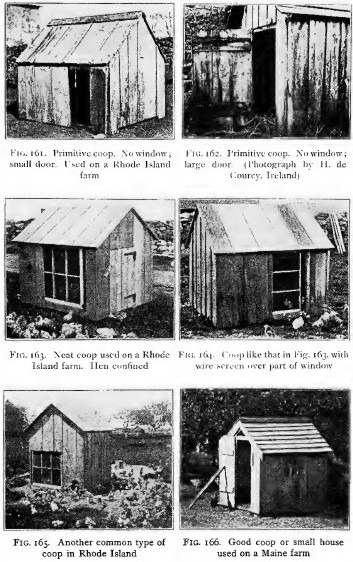

Simplest form of shelter made for poultry. The familiar style of coop called the A-shaped coop, or tent coop, in which we have shelter provided at the minimum expense for materials and labor, [106] appears to have been first made of barrel staves. This style of coop has been made in all sizes, from the small coop, barely large enough for a hen to stand and turn in, to a building capable of accommodating a hundred fowls. Such large sizes are, however, unusual. The most common size of coop of this type for a flock of adult fowls is about 8 feet square on the ground and from 6 to 8 feet high, designed to accommodate from twelve to fifteen hens. This style of coop, in small sizes, was probably designed quite as early as the barrel was used, and has been used ever since. It is not known that at any time, down to within a few years, those making such coops gave any thought to the point of conformity to correct principles. The idea in building them seems always to have been to make the cheapest thing that would serve the purpose. Those who, within the past few generations, have tried to make the best possible coops and houses for poultry have generally kept away from this type, considering it not much of an advance over the makeshift barrel coop or the improvised shelter of poles and straw or cornstalks sometimes used on farms. They overlooked [108] the fact that this type of coop, or house, if of sufficient depth from front to rear to keep the occupants protected from such storms as would beat in at the front (which was often open as in the barrel coop), provided the three essentials, ― shelter, ventilation, and, in the common sizes, appropriate height. |

La forma più semplice di ricovero costruito per il pollame . Lo stile familiare di stia chiamata stia sagomata a forma di A, o stia a forma di tenda, nella quale noi abbiamo un ricovero fornito con una spesa minima per materiali e lavoro, sembra essere stata fatta per la prima volta con doghe di barile. Questa sorta di stia è stata fatta in tutte le dimensioni, dalla piccola stia appena grande abbastanza per una gallina per stare in piedi e girarvi dentro, a un edificio capace di accomodare 100 polli. Comunque, dimensioni così grandi sono insolite. La dimensione più comune di stia di questo tipo per un gruppo di polli adulti è di circa 8 piedi quadrati sul suolo e con un’altezza da 6 a 8 piedi, progettata per accomodare da 12 a 15 galline. Questo tipo di stia, di piccole dimensioni, fu probabilmente ideato appena il barile fu usato, ed è stato usato sin da allora. Non è noto che in qualunque tempo, fino ad alcuni anni fa, coloro che facevano tali stie diedero ogni pensiero al punto di conformità a corretti principi. L'idea nel costruirli sembra sempre essere stata per fare la cosa più economica che servirebbe allo scopo. Quelli che, all'interno delle poche generazioni passate, hanno tentato di costituire le stie migliori possibili e case per pollame, sono generalmente stati lontano da questo tipo, considerandolo non più di un anticipo dell’improvvisata stia barile o l’improvvisato ricovero di paletti e paglia o steli del granturco qualche volta usati su fattorie. Trascurarono il fatto che questo tipo di stia, o casa, se di profondità sufficiente dalla fronte al retro per tenere gli occupanti protetti da tali temporali come se colpisse alla fronte (che era spesso aperta come nella stia di barile), provvedeva le tre cose essenziali ― protezione, ventilazione, e, nelle dimensioni comuni, altezza adatta. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

[108] Poultry housed under the same roof as their owner. In the British Isles the keeping of poultry in the dwelling house appears to have been quite common as recently as eighty years ago and possibly up to a much more recent date. In "The Poultry Yard: a Practical View of the Best Method of Selecting, Rearing, and Breeding the Various Species of Domestic Fowl," by Peter Boswell, of Greenlaw, the author, in describing primitive methods of keeping poultry, mentions three as specially suited to the cottager. What he calls the "simplest form" is a lean-to "at the gable end of the cottage, as near as possible to the opposite side of the kitchen fire, at which part, and for this purpose, the wall might be made thinner." As "the cottager's best" he recommends "a part of the space next the roof, so often unoccupied and useless," adding, "To accomplish the object, a part of it next the kitchen-fire gable end should be partitioned off, floored, and fitted up with baulks and laying places." When fowls were thus housed, they had access to their loft by means of a hen ladder from an opening through the outer wall to the ground. The third method, called "the cottager's own" but recommended only to those who could make no other provision for poultry, was to allow the fowls to roost in "the upper part of the space at the door" at night and run in the road by day. |

Pollame accasato sotto lo stesso tetto come il loro proprietario . Nelle Isole Britanniche l’allevamento di pollame nella casa di abitazione sembra essere stato piuttosto comune circa 80 anni fa e forse in una data molto più recente. In "Il Recinto di Pollame: una Prospettiva Pratica del Miglior Metodo di Selezionare, Allevare e Accoppiare le Varie Specie di Pollo Domestico" di Peter Boswell, di Greenlaw, l'autore, nel descrivere metodi primitivi di allevare il pollame, ne menziona 3 come specialmente adeguati all’abitante di una casetta. Ciò che lui chiama la "forma più semplice" è una capanna a una falda "nella fine della parte superiore della casetta, il più vicino possibile al lato opposto del fuoco di cucina, in quella parte, e a questo scopo, il muro potrebbe essere fatto più sottile." Come "il meglio dell’abitante della casetta" lui raccomanda "una parte dello spazio vicino al tetto, così spesso non occupato e inutile" aggiungendo "Portare a termine l'oggetto, una sua parte prossima al fuoco di cucina la fine di frontone dovrebbe essere suddivisa, pavimentò, e andò bene con grosse travi di legno e lasciando spazi." Quando i polli furono così accasati, avevano accesso alla loro soffitta per mezzo di una scala per gallina da un'apertura attraverso il muro esterno al suolo. Il terzo metodo, detto "il proprio dell’abitante di una casetta" ma raccomandato solo a quelli che non potrebbero fare altra provvista per il pollame, era permettere ai polli di appollaiarsi di notte nella "parte superiore dello spazio vicino alla porta" e girare nella strada di giorno. |

|||

|

The custom, among the poorest class, of keeping fowls in dwellings has a historical value, because it appears that the thriftiness and productiveness of many flocks so kept are largely responsible for the idea that, to lay in winter, fowls must be kept warm; this seems to have been made a fundamental principle in expert poultry-house construction long before the modern period, and until a few years ago was regarded as essential. |

L’abitudine, nella classe più povera, di allevare polli in abitazioni ha un valore storico, perché sembra che il risparmio e la produttività di molti gruppi così tenuti sono estesamente responsabili per l'idea che, per deporre in inverno, i polli devono essere tenuti al caldo; questo sembra essere diventato un principio fondamentale nella costruzione esperta delle case per il pollame molto prima del periodo moderno, e fino a pochi anni fa fu considerato come essenziale. |

|||

|

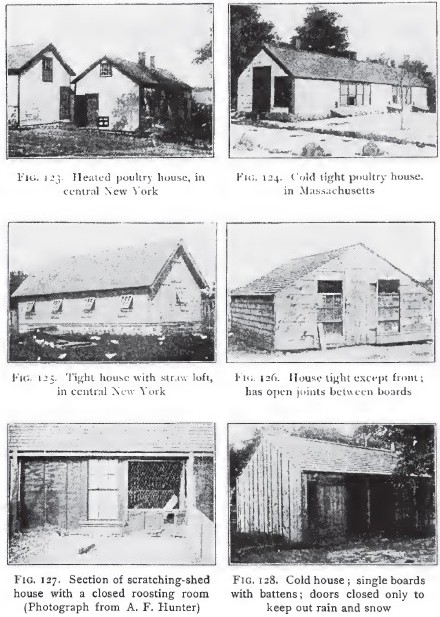

Tight houses. The theory that winter egg production depended upon high temperatures led naturally to the construction of tight houses. That having been assumed, it was necessary either to heat the houses artificially or to so construct them that they would [111] exclude cold and retain the heat thrown off by the occupants. Artificial heating was often tried and usually discarded after a short trial as of no advantage, though in a trip through central New York some years ago the author found many poultry houses in which large stoves were used and considered an advantage. In general, it was thought better to build houses tight and warm. To accomplish this, various methods were used. The cheapest construction supposed to answer the purpose was made by covering the frame of the house with boards, and these with two thicknesses of building paper, the outer one weatherproof. For more effective protection [112] from cold, it was common to use double boards with paper between and weatherproof paper over the outer boards. Sometimes the outside was shingled over a paper sheathing. Many houses were built with dead-air spaces throughout the walls, made by putting one layer of boards and one of paper on each side of the studding. Occasionally houses were lathed and plastered inside. The limit was probably reached by a poultryman in an eastern state who made his walls with three thicknesses of boards, three of paper, and two dead-air spaces. In harmony with such construction were the tight-fitting doors and windows used, both doors and windows often being double. |

Case chiuse. La teoria che la produzione dell’uovo in inverno dipendeva dalle alte temperature portò naturalmente alla costruzione di case chiuse. Essendo stato ipotizzato ciò, era necessario scaldare artificialmente le case o costruirle in modo tale che potessero escludere il freddo e trattenere il calore prodotto dagli occupanti. Il riscaldamento artificiale fu spesso provato e di norma dopo una breve prova scartato come di nessun vantaggio, sebbene in un viaggio attraverso il centro dello stato di New York l'autore alcuni anni fa trovò molte case di pollame nelle quali erano usate grandi stufe e considerate un vantaggio. In generale, si pensava fosse meglio costruire case chiuse e calde. Vari metodi furono usati per realizzare ciò. La costruzione ipotizzata più economica nel rispondere allo scopo fu fatta coprendo l’intelaiatura della casa con delle assi, e queste con due strati di carta da costruzioni, l'esterno impermeabile. Per una protezione più efficace dal freddo era comune usare assi duplici con carta fra e carta impermeabile sopra le assi esterne. Qualche volta l’esterno fu ricoperto con assicelle su un rivestimento di carta. Molte case furono costruite con spazi di intercapedine attraverso i muri, fatti mettendo uno strato di assi e uno di carta su ogni lato dei montanti. Di quando in quando delle case erano ricoperte di assicelle e intonacate all’interno. Il limite probabilmente fu raggiunto da un avicoltore in un stato orientale che fece i suoi muri con 3 strati di assi, 3 di carta e 2 spazi di intercapedine. In armonia con tale costruzione erano le porte e le finestre strette usate, essendo spesso duplici sia le porte che le finestre. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

[112] Ventilation in tight houses. Theoretically, ventilation was furnished either by ventilators alone or by ventilators supplemented, during fine weather or through the warmer hours of the day, by careful adjustment of doors and windows; but many houses were built without ventilators, on the theory that the building contained air enough to supply the fowls for several days, if doors and windows were closed as long as that. That the ventilators usually did not ventilate was shown by the fact that the houses, when closed, became damp and moisture condensed on the wall just as often when an approved method of ventilating through ventilators was used as when no ventilators were provided. |

Ventilazione in case chiuse . Teoreticamente la ventilazione era fornita o solo da ventilatori o da ventilatori integrati, durante il bel tempo o durante le ore più calde del giorno, con adattamento accurato di porte e finestre; ma molte case erano costruite senza ventilatori, in base alla teoria che l'edificio conteneva abbastanza aria da provvedere i polli per molti giorni, se porte e finestre fossero chiuse così a lungo. Che i ventilatori di solito non ventilavano era dimostrato dal fatto che le case, quando chiuse, diventavano umide e l’umidità si condensava sul muro proprio frequentemente quando un metodo approvato di ventilare per mezzo di ventilatori era usato come quando nessun ventilatore era fornito. |

|||

|

In the light of recent experiences with cold houses it seems probable that the failures of most of the old methods of ventilation were due to the small sizes of ventilators used. The ineffectiveness of these was often aggravated by obstructions in the ventilator designed to prevent a too rapid movement of air. In warm houses the problem of securing sufficient ventilation while retaining the heat is a serious one, especially when moisture collects on interior walls and the litter on the floors becomes damp and the air inside the house moist and foul. The most satisfactory solutions of the problem were the straw loft and the open-front scratching-shed house, the first designed to overcome by absorption the dampness in the closed house, the other providing abundance of fresh air in the daytime. |

Alla luce di recenti esperienze con case fredde sembra probabile che i fallimenti della maggior parte dei vecchi metodi di ventilazione fossero dovuti alle piccole dimensioni dei ventilatori usati. La loro inefficienza fu spesso aggravata da ostruzioni nel ventilatore destinate a prevenire un movimento troppo rapido dell’aria. Nelle case calde è un problema serio quello di assicurare una ventilazione sufficiente trattenendo il calore, specialmente quando raccoglie umidità su muri interni e lo strame sui pavimenti diventa umido e l'aria all’interno della casa umida e fetida. Le soluzioni più soddisfacenti del problema erano la soffitta di paglia e la casa aperta di fronte con tettoia graffiante, la prima progettata per sopraffare l'umidità nella casa chiusa attraverso l’assorbimento, l'altra provvedendo abbondanza di aria fresca durante il giorno. |

|||

|

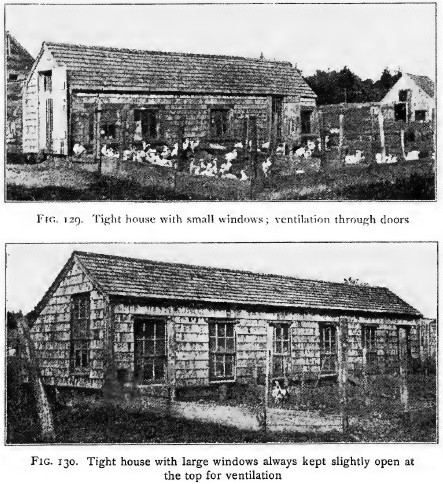

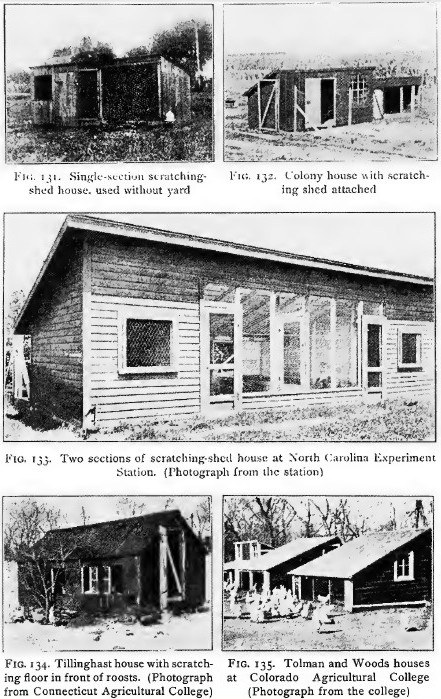

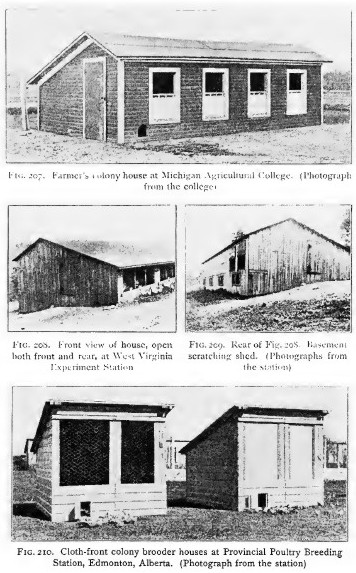

Beginning of the fresh-air movement. The scratching-shed house was a marked step in the direction of right principles of poultry-house construction, and toward the open, thoroughly [113] ventilated house, which, it is now generally agreed, is, all things considered, the best type of poultry house. Houses of the open-front scratching-shed type have been used here and there since the middle of the last century, but it was not until after 1890, when the extension of interest in poultry was increasing the number of those who were having trouble in warm houses, that any general interest was manifested in them. Then for a few years they were exploited as a remedy for the difficulties in warm houses, and became very popular. The term "open-front scratching-shed house" was applied particularly to the plan used and exploited by one man, but the idea was applied, in variously modified forms, to many other styles of houses. As is usual, the merits were much exaggerated. |

Inizio del movimento di aria fresca . La casa con tettoia graffiante era un passo notevole in direzione dei corretti principi di costruzione della casa per pollame, e verso quella aperta, casa completamente ventilata che, ora è generalmente ammesso, considerate tutte le cose, è il miglior tipo di casa per pollame. Case del tipo aperta di fronte con tettoia graffiante sono usate qua e là fin dalla metà dell'ultimo secolo, ma è stato solo dopo il 1890, quando l’estensione di interesse nel pollame stava aumentando il numero di quelli che stavano avendo difficoltà in case calde, che ogni generale interesse fu manifestato per esse. Quindi per alcuni anni furono sfruttate come un rimedio per le difficoltà nelle case calde, e divennero molto popolari. Il termine "casa aperta di fronte con tettoia graffiante" fu applicato particolarmente al progetto usato e sfruttato da un uomo, ma l'idea fu applicata, in forme variamente modificate, a molti altri stili di case. Come è abituale, i meriti furono molto esagerati. |

|||

|

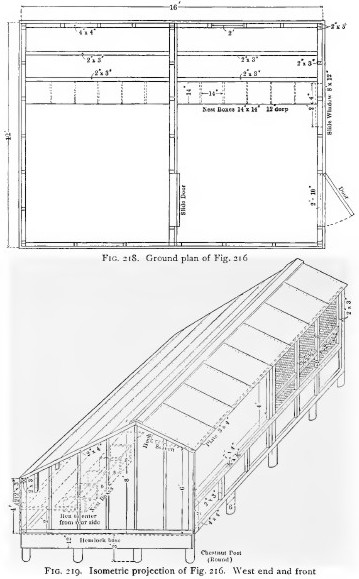

Experience with the open-front scratching-shed house showed that the fowls would remain in the open shed the greater part of the daytime, and that the capacity of the two compartments thus became only the capacity of the one compartment that the birds frequented. The open front of the scratching shed was intended to be open only during fine weather. At other times it was to be closed with curtains, which were at first of oiled cotton cloth on frames. This material was used and recommended as an economical substitute for glass sash. The difficulty, in many places, of getting oiled cloth led to a very general substitution of ordinary cheap cloth and burlap, both of which admitted considerable air through the meshes. Improved conditions as a result of better air thus supplied brought about a very general use of such materials in place of glass in a part or all of the windows of closed houses. |

L’esperienza con la casa aperta di fronte con tettoia graffiante mostrò che i polli rimarrebbero nel capannone aperto la maggior parte del giorno, e che la capacità dei due compartimenti divenne così solamente la capacità del solo compartimento che gli uccelli frequentavano. La fronte aperta della tettoia graffiante si decise che fosse aperta solo durante un bel tempo. In altri tempi doveva essere chiusa con tende che erano innanzitutto di un panno di cotone oliato su intelaiature. Questo materiale fu usato e raccomandato come un sostituto economico per il telaio di vetro. La difficoltà, in molti luoghi, di prendere del panno oliato portò a una molto generale sostituzione della stoffa ordinaria poco costosa e della tela ruvida, e ambedue lasciarono entrare considerevole aria attraverso le maglie. Le condizioni migliorate come risultato di aria migliore così fornita portò quasi un uso molto generale di tali materiali al posto del vetro in una parte o in tutte le finestre di case chiuse. |

|||

|

The idea that fowls must be kept warm was a fundamental principle in the management of fowls in scratching-shed houses and in the numerous adaptations of the plan made in houses of other types. The birds were to be kept warm by constant exercise in the litter in which their grain was fed on the floor of the scratching shed, or scratching room (as the case might be), while at night they kept warm in the close roosting room, or the reduced form of it called the roosting closet, or roost box, built with a hinged front or burlap curtain to retain the heat when the fowls were on the roost. It was commonly observed that fowls were likely to be more thrifty and free from disease in these houses when the keeper neglected to take precautions to keep them warm at night. Again, when [114] curtains of cotton cloth and burlap exposed to the weather were rotted out, it was not uncommon to delay renewing them, and no bad effects seemed to follow. Such things, and numerous instances remembered or observed of flocks of fowls doing well through cold winters in mere shells of houses, gradually broke down in many minds the notion that fowls must have warm houses, until, in the early years of this century, progressive poultry keepers began to realize that many of the despised makeshifts and flimsy structures of more primitive times, and of shiftless poultry keepers of their own times, were essentially better than their best structures designed according to principles upon which they had been working. |

L'idea che i polli devono essere tenuti caldi era un principio fondamentale nella gestione dei polli in case con tettoia graffiante e nei numerosi adattamenti del progetto fatti in case di altri tipi. Gli uccelli dovevano essere tenuti caldi da un continuo esercizio nella lettiera in cui le loro granaglie erano messe sul pavimento della tettoia graffiante, o stanza graffiante (come sarebbe il caso), mentre di notte prendevano il caldo nella chiusa stanza per appollaiarsi, o la sua forma ridotta detta armadio a muro che fa appollaiare, o cassa per appollaiarsi, costruito con una fronte provvista di cardini o tenda di tela ruvida per trattenere il calore quando i polli erano sul posatoio. Fu comunemente osservato che i polli erano probabilmente più frugali e liberi da malattia in queste case quando l’allevatore trascurava di prendere le precauzioni per tenerli caldi di notte. Inoltre, quando tende di stoffa di cotone e tela ruvida esposte al tempo erano decomposte, non era insolito ritardare nel rinnovarle, e sembrava che non ne risultasse alcun cattivo effetto. Tali cose, e numerosi esempi ricordati o osservati di gruppi di polli che stanno bene attraverso inverni freddi in soli gusci di case, gradualmente si spezzò in molte menti l’idea che i polli devono avere le case calde, fino a quando, nei primi anni di questo secolo, dei progressisti allevatori di pollame cominciarono a comprendere che molti degli espedienti disprezzati e delle fragili strutture di tempi più primitivi, e di allevatori di pollame incapaci dei loro propri tempi, era essenzialmente meglio rispetto alle loro migliori strutture progettate secondo principi sui quali loro stavano lavorando. |

|||

|

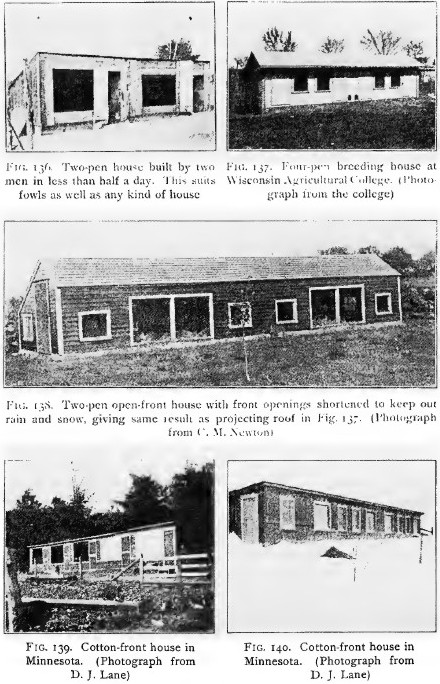

Houses with open fronts. In these, as is to be expected, considerable variety is found, but in general a house of this type belongs to one of two classes: Either it is an open house of such proportions, and with roosts so placed, that, theoretically, the fowls, when roosting, are kept warm, because they are so far from the open front and the rate of movement of air in the house is so slow that a considerable part of the heat they diffuse benefits them; or it is a cold house, in which the heat thrown off by the birds can have no appreciable effect on the temperature about them. In houses of the first class the air entering the front is supposed to make no draft to which the fowls on the roosts would be exposed; in houses of the second class drafts are disregarded. Those who advocate and use the warm open-front house have apparently not fully abandoned the idea that the fowls must be kept in a temperature sensibly higher than that outside, and must be protected from direct currents of air entering the house from without. Those who advocate and use cold houses hold that, within a limit (practically the degree of frost that the combs of the male birds will withstand), fowls may be accustomed to low temperatures; that it is not the absolute degree of cold that injures them or stops egg production, but the variations of temperature; and that fowls accustomed to the lowest temperatures and free supplies of fresh air are least affected by these. |

Case con facciate aperte . In queste, come ci si deve aspettare, si trova una considerevole varietà, ma in generale una casa di questo tipo appartiene a una di due classi: O è una casa aperta di tali proporzioni, e con posatoi così collocati, che, teoreticamente, i polli, quando si appollaiano, sono tenuti caldi, perché sono tanto lontani dalla facciata aperta e la percentuale di movimento dell’aria nella casa è così lento che una parte considerevole del calore che loro diffondono li avvantaggia; o è una casa fredda in cui il calore eliminato dagli uccelli non può avere effetto apprezzabile sulla temperatura intorno a loro. In case di prima classe si suppone che l'aria che entra di fronte non faccia alcun effetto al quale sarebbero esposti gli uccelli sui posatoi; in case di seconda classe gli effetti sono trascurati. Quelli che sono in favore e usano la casa calda con facciata aperta, a quanto pare non hanno completamente abbandonato l'idea che i polli devono essere tenuti a una temperatura sensibilmente più alta di quella esterna, e deve essere protetta da correnti continue di aria che entra in casa da fuori. Quelli che sono in favore e usano case fredde ritengono che, entro un limite (praticamente il grado di gelo che le creste degli uccelli maschi sopporteranno), i polli possono essere abituati a temperature basse; che non è il grado assoluto di freddo che li danneggia o blocca la produzione di uova, ma le variazioni di temperatura; e che i polli abituati alle temperature più basse e a liberi rifornimenti di aria fresca sono meno colpiti da esse. |

|||

|

No best house. There are not marked regular variations of results in houses differing as to warmth or any other one feature. The fact that results equally good in every way have been obtained in many different types of houses under a great variety of [116] conditions shows that the important thing is not that a building for poultry shall be of a particular pattern, but that, whatever its pattern, conditions in it be regulated to meet the requirements of the birds for fresh air and dry quarters. This can be done in any type of house that is not radically wrong. But the warmer the birds are kept, ― the higher the range of temperature to which they are accustomed, ― the more necessary it is that the attendant give close attention to ventilating through doors and windows, and in practice it is too often found impossible to attend to this at the proper times. The cold open house may be so constructed as to require no manipulation whatever for ventilation and no attention to doors and windows except for the exclusion of rain and snow. Between these extremes are intermediate types requiring much or little regulation according to construction and arrangement. Each has its place. Whoever keeps a delicate breed, or one having a tender feature, in a cold locality must use warm houses and give as much attention as necessary to proper regulation of conditions in them. Whether it is more profitable to do this than to keep a hardier breed in a cheaper building, with less labor, is a point that each must determine for himself. |

Nessuna casa migliore . Non ci sono spiccate variazioni regolari di risultati in case che differiscono per il calore o per ogni altra caratteristica. Il fatto che risultati ugualmente buoni sono stati ottenuti in tutto e per tutto in molti tipi diversi di case con una grande varietà di condizioni dimostra che la cosa importante non è che un edificio per pollame sia di un particolare modello, ma che, qualunque sia il suo modello, le condizioni in esso siano regolate in modo tale da soddisfare le esigenze degli uccelli per aria fresca e ambienti asciutti. Questo può essere fatto in qualunque tipo di casa che non è radicalmente errata. Ma più gli uccelli sono tenuti al caldo ― il più alto grado di temperatura cui sono abituati ― più è necessario che il guardiano dedichi stretta attenzione a ventilare attraverso porte e finestre, e in pratica molto spesso è stato impossibile occuparsi di ciò in tempi opportuni. La casa fredda aperta può essere costruita in modo tale da non richiedere alcuna manipolazione per la ventilazione né alcuna attenzione per porte e finestre eccetto che per escludere pioggia e neve. Tra questi estremi ci sono tipi intermedi che richiedono molta o poca regolazione a secondo della costruzione e della sistemazione. Ognuna ha il suo luogo. Chiunque allevi una razza delicata, o una che ha una fattezza delicata, in una località fredda, deve usare case calde e dare loro la massima attenzione necessaria per una corretta regolazione delle condizioni. Se è più proficuo fare questo che allevare una razza più forte in un edificio più economico, con meno lavoro, è un punto che ognuno deve fissare per se stesso. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

[116] Floor dimensions. In a structure for poultry the floor area is determined on the basis of the number of birds to be kept in it and the proportion of time that they are to be confined to it. The space per bird required varies inversely with the number of birds in the flock, small flocks requiring much more space per bird than large flocks, because the bird is not like a plant or a tree, or like horses and cattle in barns, located in one place and constantly occupying it, but each bird in the flock has the use of the entire floor, less only the space actually occupied by its mates. A flock of ten or twelve hens can be comfortably housed in a building 8 feet square (which allows 5 or 6 square feet of floor space per fowl), if they can get outside for a good part of the time. If confined almost constantly to the house, the same flock should have about 50 per cent more floor space. With increasing size of flocks the "per hen" space may be reduced gradually until from seventy-five to a hundred hens have about 4 square feet each. Very small flocks need relatively large "per hen" areas. A single bird needs almost as much room as ten or twelve. |

Dimensioni del pavimento . In una struttura per pollame l'area del pavimento è determinata in base al numero di uccelli che vi debbono essere tenuti e alla percentuale di tempo in cui vi debbono essere confinati. Lo spazio richiesto per un uccello varia inversamente al numero di uccelli nel gruppo, in quanto i piccoli gruppi richiedono molto più spazio per uccello rispetto ai grandi gruppi, in quanto l'uccello non è come una pianta o un albero, o come cavalli e bestiame bovino in fienili, localizzati in un luogo e occupandolo costantemente, ma ogni uccello nel gruppo ha l'uso dell’intero pavimento, solo meno lo spazio realmente occupato dai suoi compagni. Un gruppo di 10 o 12 galline può comodamente essere accasato in un edificio di 8 piedi quadrati (che permette 5 o 6 piedi quadrati di spazio di pavimento per uccello), se possono stare fuori per una buona parte del tempo. Se è relegato in casa quasi continuamente, lo stesso gruppo dovrebbe avere circa il 50 % di spazio di pavimento in più. Con l’aumento delle dimensioni dei gruppi lo spazio "per gallina" può essere gradualmente ridotto fino a che da 75 a 100 galline abbiano circa 4 piedi quadrati ognuno. Gruppi molto piccoli hanno bisogno di aree "per gallina" relativamente grandi. Un solo uccello ha bisogno di circa tanto spazio quanto per 10 o 12. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

[118] Height of poultry structures. In small structures which the attendant does not have to enter, or enters infrequently, the height of the building is usually adapted to the poultry; in larger structures it is adapted to the attendant. The lower houses furnish the best conditions for the birds, but, though that point has not been carefully investigated, it does not appear that the conditions in a house three or four feet high are so materially better than in a house high enough for a man to stand and work in (about six feet) as to make it advisable to reduce the height when that would mean a reduction of floor space and of the size of flocks. |

Altezza delle strutture per il pollame . Nelle piccole strutture in cui il guardiano non deve entrare, o entra raramente, l'altezza dell'edificio è di solito adattata al pollame; nelle più grandi strutture è adattata al guardiano. Le case più basse forniscono le migliori condizioni per gli uccelli, ma, sebbene tale punto non sia stato attentamente investigato, non sembra che le condizioni in una casa alta 3 o 4 piedi siano materialmente tanto migliori rispetto a una casa alta abbastanza per un uomo per stare in piedi e lavorarvi (circa 6 piedi) come se fosse opportuno ridurre l'altezza quando ciò significherebbe una riduzione di spazio del pavimento e della taglia dei gruppi. |

|||

|

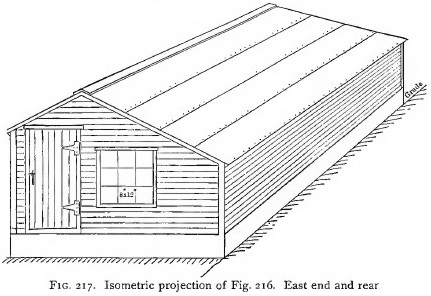

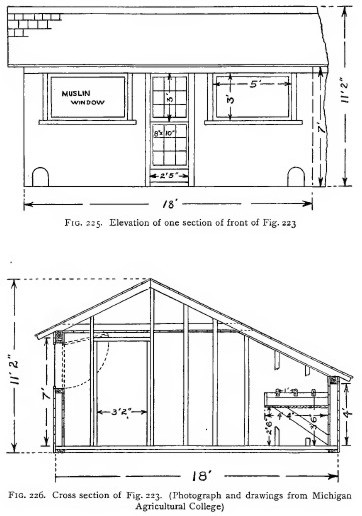

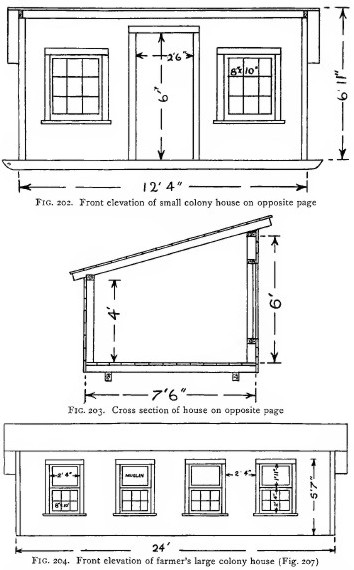

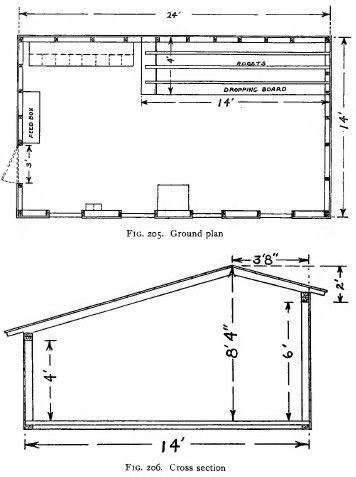

Depth of poultry structures. The depth of poultry structures should be proportionate to their height. In order that an interior may be properly sunned and ventilated, the depth, or distance from the front to the rear wall, must bear such proportion to the height of the front wall that sunlight will penetrate well back. As the elevation of the sun varies with the seasons, it is manifestly impossible to make a structure of fixed height and width in which the desired condition will be obtained at all seasons, but if the height of the front be about half the width of the building, the average conditions will be as nearly right in this respect as they can be made. Since it has already been determined that the height of the larger shelter for poultry should be near the minimum height of a building in which a man can work expeditiously, it follows that the fixing of such a standard of height, and of the relation of height to width, limits the width to about twelve or fourteen feet. |

Profondità delle strutture per pollame . La profondità di strutture per pollame dovrebbe essere proporzionata alla loro altezza. Affinché un interno possa essere adeguatamente soleggiato e ventilato, la profondità, o distanza tra facciata e muro posteriore, deve avere una tale proporzione nell'altezza del muro anteriore che la luce del sole penetrerà bene fino sul retro. Siccome l'elevazione del sole varia con le stagioni, è chiaramente impossibile fare una struttura di altezza e ampiezza fisse in cui la condizione desiderata sarà ottenuta in tutte le stagioni, ma se l'altezza della facciata è di metà larghezza dell'edificio, le condizioni medie saranno sotto questo aspetto quasi giuste come possono essere fatte. Siccome è già stato determinato che l'altezza del più grande ricovero per pollame dovrebbe essere vicina alla minima altezza di un edificio in cui un uomo può lavorare rapidamente, ne segue che la fissazione di un tale standard di altezza, e della relazione tra altezza e larghezza, limiti la larghezza a circa 12 o 14 piedi. |

|||

|

In a single house, or in a two-pen house which may be lighted and ventilated with windows or doors on the sides in addition to those in the front (south), the depth may be as much greater as desired, the side openings carrying light and air back. This arrangement is not adapted to the continuous-house plan with more than two pens, because the side openings affect only the end compartments. It is not nearly so much used as the plan with all openings in the front. Its advantage is most obvious when it is desired to make for a larger flock a compartment that will be well lighted and ventilated without increasing the height or making the length so great that the faults of long, narrow houses will be introduced. Even with the use of side openings the depth is rarely increased more than 50 per cent over what it would be by the rule given. |

In una casa singola, o in una casa con 2 recinti che può essere illuminata e ventilata con finestre o porte sui lati oltre a quelle sulla facciata (sud), la profondità può essere grande come desiderato, le aperture dei lati portando di nuovo luce e aria. Questa sistemazione non è adattata al piano di casa continua con più di 2 recinti, perché le aperture di lato influiscono solo sui compartimenti finali. Non è quasi usato tanto come il piano con tutte le aperture nella facciata. Il suo vantaggio è molto ovvio quando si desidera costituire per un gruppo più grande un compartimento che sarà ben illuminato e ventilato senza aumentare l'altezza o fare la lunghezza grande come i difetti di lunghezza, case strette saranno presentate. Anche con l'uso di aperture laterali la profondità è raramente aumentata più del 50% su quello che sarebbe dato dalla regola. |

|||

|

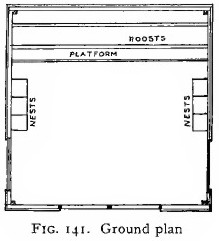

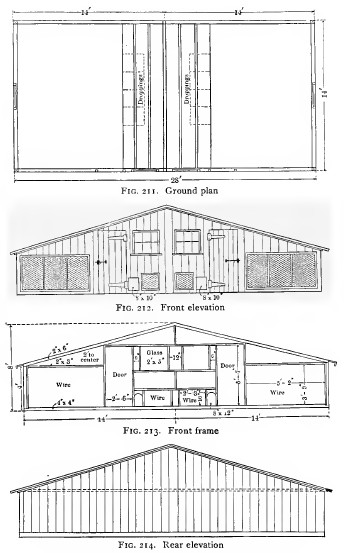

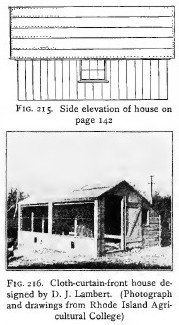

[119] Standard-size poultry-house unit. Taking 6 feet as the most convenient standard for a full-height poultry house, and 12 feet as the most appropriate depth for a house of that height, we have two of the dimensions for a standard unit of size of poultry house. The advantages of a square floor over others (to be explained shortly) make it fitting to have the third dimension the same as the second (12 feet). This makes the standard-size single house or compartment 6 ft. x 12 ft. x 12 ft. This is a medium in form and dimensions for single houses, and nearly all the common plans of houses may be treated as modifications of it; on the whole, the most convenient unit for a continuous or compartment house. Diagrams of a single standard-size poultry house will be found on page 121. |

Unità casa di pollame di grandezza standard . Assumendo 6 piedi come lo standard più conveniente per una casa di pollame di piena altezza, e 12 piedi come la profondità più adatta per una casa di tale altezza, noi abbiamo 2 delle dimensioni per un'unità standard di grandezza di una casa di pollame. I vantaggi di un pavimento quadrato su altri (per essere spiegato in breve) lo fanno andare bene per avere la terza dimensione uguale alla seconda (12 piedi). Questo rende la casa singola di grandezza standard o compartimento pari a 6 piedi x 12 piedi x 12 piedi Questa è una misura media per forma e dimensioni per case singole, e quasi tutti i piani comuni di case possono essere trattati come sue modifiche; tutto considerato, l'unità più conveniente per una casa continua o di compartimento. Diagrammi di una singola casa di pollame di grandezza standard saranno trovati a pagina 121. |

|||

|

The use of such a standard or basic unit in the study of poultry-house plans should not be misunderstood. It may be, and often is, desirable to vary these dimensions, but such a house has capacity at all seasons, in all climates, for as large a flock of average adult fowls as the average poultry keeper handles to advantage, is convenient for a person of any height, may be fully sunned and aired by means of openings in the front, and is adapted to single-compartment construction or to any number of compartments; while the measurements are such that, in nearly all dimensions of lumber required in construction, 12-foot lengths cut to advantage. A house of these dimensions is no better than one differing somewhat from them, but these measurements are most suitable for a standard, for a basis of a comparison of features in poultry houses, and for a base from which to work in designing poultry houses. Variations from them should be made for a definite purpose. If they accomplish that purpose without introducing something objectionable, they give a better style of building for the purpose. If a change introduces objectionable features as well as advantages, these must be considered and the right adjustment found. These points will be illustrated in the descriptions and discussions of various features of poultry houses in following paragraphs. |

L'uso di una tale unità standard o di base nello studio dei piani di casa per pollame non dovrebbe essere frainteso. Può essere, e spesso lo è, desiderabile variare queste dimensioni, ma tale casa ha capacità in tutte le stagioni, in tutti i climi, per un grande gruppo di polli mediamente adulti come il custode di pollame medio gestisce con vantaggio, è conveniente per una persona di qualunque altezza, può essere soleggiato pienamente e aerato per mezzo di aperture sulla facciata, ed è adattato alla costruzione di un compartimento singolo o a qualunque numero di compartimenti; mentre le misurazioni sono tali che, in quasi tutte le dimensioni di legname richieste in una costruzione, lunghezze di 12 piedi tagliano a vantaggio. Una casa di queste dimensioni non è migliore di una che differisce alquanto da esse, ma queste misurazioni sono molto appropriate per uno standard, per una base di un paragone di caratteristiche in case di pollame, e per una base da cui lavorare nel progettare case di pollame. Variazioni da esse dovrebbero essere fatte per uno scopo definito. Se portano a termine tale scopo senza introdurre qualcosa di deplorevole, danno uno stile migliore di costruire per lo scopo. Se un cambio inserisce caratteristiche deplorevoli come anche vantaggi, questi devono essere considerati e la rettifica corretta deve essere trovata. Questi punti saranno illustrati nei paragrafi seguenti nelle descrizioni e discussioni di varie caratteristiche di case per pollame. |

|||

|

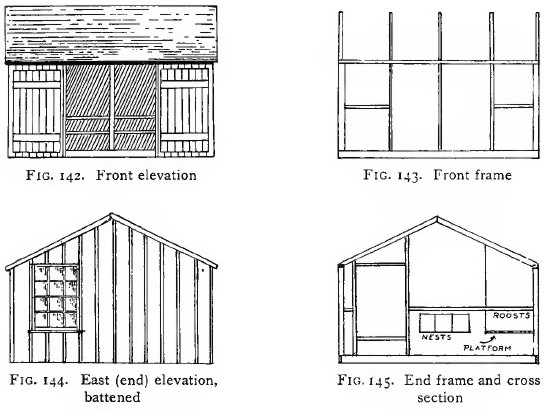

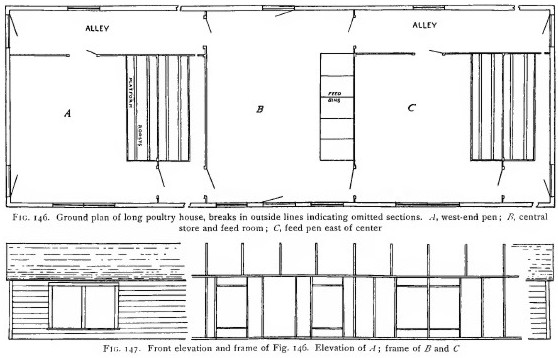

Length of poultry structures. The length (front) of a single poultry house (or section) should approximately equal its depth or width. The greatest economy of space and construction is attained in a square building. There are, however, some advantages [120] in making the length a little greater than the width. The floor space (and so the capacity of the house) may be increased without changing height and width or materially affecting any interior condition. If the outside runs must correspond with the width of the house, the width and area of the run are very materially increased. An increase of 25 per cent in area over the standard may be made in this way, but it is not advisable to attempt to add still more room in one house and run by this means. Houses have been built, of standard width and height, with length up to or over one hundred feet and used for one large flock. At one time, also, the continuous long house, divided into many compartments by partitions of wire netting or slats, was a favorite. Many houses of that type may still be found. But in common experience it is found advisable to limit the length of the house, or of a compartment, to very nearly its width. One reason for this is that the flock in an almost square room is less disturbed by the attendant moving about; the birds have more room to pass him. In a long house the birds, if at all shy, will rush to the end of the house, and if the flock is large, the disturbance and crowding may be serious. In all very long houses that the writer has seen in use, the flock, though large for a single flock, has been only about half the total number that could be carried in the same space in compartments of standard size. |

Lunghezza delle strutture per pollame . La lunghezza (facciata) di una singola casa per pollame (o sezione) dovrebbe uguagliare all'incirca la sua profondità o ampiezza. La più grande economia di spazio e costruzione è raggiunta in un edificio quadrato. Ci sono comunque dei vantaggi nel fare la lunghezza un po’ più grande dell'ampiezza. Lo spazio del pavimento (e così la capacità della casa) può essere aumentato senza cambiare altezza e ampiezza o influendo materialmente qualunque condizione interna. Se le lunghezze esterne devono corrispondere con l'ampiezza della casa, l'ampiezza e l'area della lunghezza sono materialmente molto aumentate. Un aumento del 25% in area al di sopra dello standard può essere fatto così, ma non è consigliabile tentare di aggiungere ancor più spazio in una casa e procedere con questo mezzo. Case sono state costruite, di ampiezza e altezza standard, con lunghezza al di sopra di o oltre 100 piedi e usate per un grande gruppo. In un'occasione, inoltre, la casa lunga e continua, divisa in molti compartimenti da sezioni di rete metallica o assicelle, era una favorita. Molte case di quel tipo possono ancora essere trovate. Ma per comune esperienza è risultato consigliabile limitare la lunghezza della casa, o di un compartimento, a valori molto vicini alla sua ampiezza. Una ragione per questo è che il gruppo in una stanza quasi quadrata è meno disturbato dal custode che si muove intorno; gli uccelli hanno più spazio per farlo passare. In una casa lunga gli uccelli, se del tutto paurosi, si precipiteranno verso la fine della casa, e se il gruppo è grande, il disturbo e l’accalcarsi possono essere seri. In tutte le case molto lunghe che lo scrittore ha visto in uso, il gruppo, sebbene grande per un solo gruppo, è stato solo circa la metà del numero totale che potrebbe essere ospitato nello stesso spazio in compartimenti di grandezza standard. |

|||

|

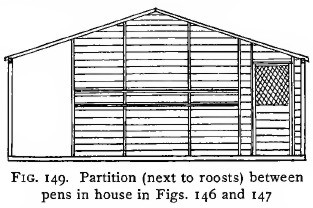

The objection to the long house with many compartments and open partitions between is that the air draws through a long, narrow, low house as through a huge flue, making the house very uncomfortable. It is found in practice that it is not advisable to build a house of this type without making every third or fourth partition solid, and most poultrymen using houses of this kind prefer to make every other partition solid. In a house of the dimensions recommended, it does not appear that there is any advantage in making every partition between pens tight; but in long houses of greater height and width the draft may be so great as to make it advisable to do this. |

L'obiezione alla casa lunga con in mezzo molti compartimenti e sezioni aperte è che l'aria scorre attraverso una lunga, stretta, bassa casa come attraverso una condotta enorme, rendendo la casa molto scomoda. Si è trovato in pratica che non è consigliabile costruire una casa di questo tipo senza rendere solida ogni terza o quarta sezione, e la maggior parte di avicoltori che usa case di questo genere preferisce fare ogni altra sezione solida. In una casa delle dimensioni raccomandate non sembra che ci sia alcun vantaggio nel fare ogni sezione tra recinti stretta; ma in case lunghe di più grande altezza e ampiezza la stesura può essere così grande come farla consigliabile a fare questo. |

|||

|

Thus it is evident that, to make the best house conditions for the poultry, the quarters for each flock, or family, whether detached from the quarters of other flocks or adjoining them, must be complete. Then the long house of many compartments appears [121] not as a single house but as a series of standard houses so placed that the sides and roofs are continuous, and that one end of each house, after the first, may be dispensed with. |

Così è evidente che, per fare le migliori condizioni di casa per il pollame, gli alloggi per ogni gruppo, o famiglia, se distaccato dagli alloggi di altri gruppi o confinando con loro, devono essere completi. Quindi la casa lunga di molti scompartimenti appare non come una casa singola ma come una serie di case standard così messe che i lati e i tetti sono continui, e che una fine di ogni casa, dopo la prima, può essere esentata. |

|||

|

The significance of the distinction is that when the continuous house is considered and constructed as a series of standard-size houses, the conditions desirable in a poultry house are obtained in the same way in every part of the series, but that when the series is regarded as the unit, almost invariably a construction seems admissible which gives different conditions in different divisions, and very unsatisfactory conditions in most of them. |

Il significato della distinzione è che quando la casa continua è considerata e costruita come una serie di case di dimensioni standard, le condizioni desiderabili in una casa di pollame sono ottenute nello stesso modo in ogni parte della serie, ma che quando la serie è considerata come l'unità, quasi invariabilmente una costruzione sembra ammissibile se dà condizioni diverse in divisioni diverse, e condizioni molto insoddisfacenti nella maggior parte di loro. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

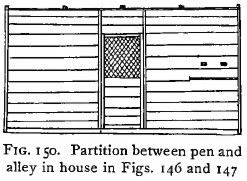

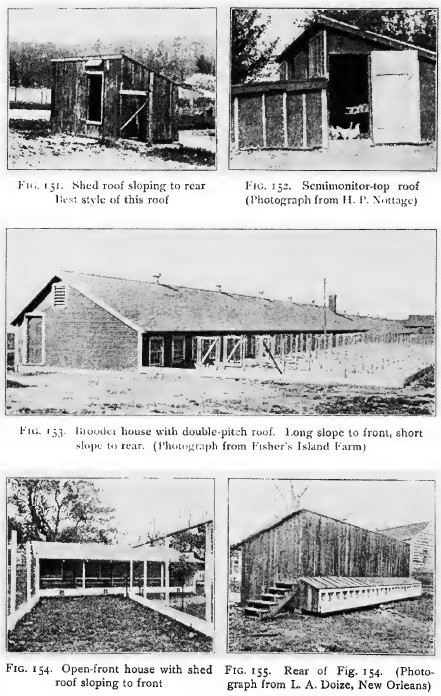

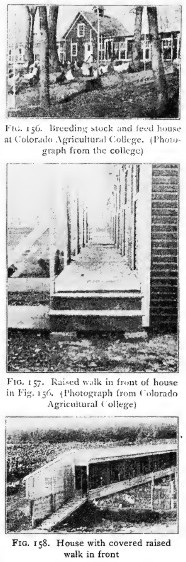

Styles of roof. The equal-slope double-pitch roof and the shed roof are the styles of roof most used for poultry houses. In single, very nearly [123] square, structures the sides of a double-pitch roof may face either north and south or east and west. In houses with two or more compartments a double-pitch roof must, as a rule, face north and south; in single-compartment houses the tent-roof type of construction may be used (or approached), with sides very low and the slopes of the roof facing east and west. Shed or single-pitch roofs on single-compartment houses may pitch in any direction desired; on houses with two or more compartments they must, as a rule, pitch either north or south, ― and preferably south, because that gives the greatest amount of sun in the house with the most economical construction. Besides these simple styles of roof several others are occasionally used. |

Stili del tetto . Il tetto in duplice pece di uguale pendio e il tetto del capannone sono gli stili di tetto più usati per case da pollame. In fila indiana, molto vicine al quadrato, strutture coi lati di un tetto in duplice pece possono affacciarsi sia a nord che a sud o a est e a ovest. In case con 2 o più compartimenti un tetto in duplice pece deve, come regola, affacciarsi a nord e a sud; in case a singolo compartimento il tipo di costruzione tetto a tenda può essere usato (o avvicinato), con lati molto bassi e i pendii del tetto che si affacciano a est e a ovest. Capannone o tetti in singola pece su case con singolo compartimento possono dare un'inclinazione in qualunque direzione desiderata; su case con 2 o più compartimenti devono, come regola, dare un'inclinazione o nord o sud ― e preferibilmente a sud, perché questa fornisce con una costruzione più economica il più grande ammontare di sole nella casa. Oltre a questi semplici stili di tetto molti altri sono usati di quando in quando. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

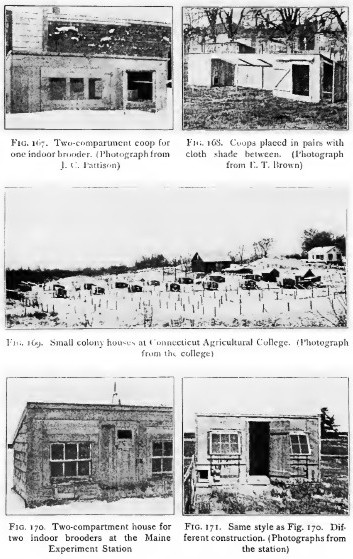

Double-pitch roofs with unequal sides are sometimes made to adapt the roof to other features of construction. Thus in some brooder houses with sunken walks in the rear, the roof has a long pitch to the south, over the pens, and a short pitch to the north, over the walk. In some of the open-front plans of houses, too, the front slope of the roof is longer than the other, and sometimes at a different angle. In what is known as the semimonitor-top style of construction the part of the house under the front slope is several feet lower than that under the rear slope of the roof, to allow placing windows in the [125] perpendicular space above the lower roof, for the better lighting and ventilation of the rear part of the house. Occasion for introducing such features usually indicates fault in the general design of the structure. |

Tetti in duplice pece con lati disuguali qualche volta sono fatti per adattare il tetto alle altre caratteristiche della costruzione. Così in alcune case per covatrice con passeggiate incavate nel retro, il tetto ha una pece lunga verso sud, sui recinti e una corta pece verso nord, sulla passeggiata. Anche in alcuni dei piani della facciata aperta delle case il pendio anteriore del tetto è più lungo dell'altro, e qualche volta con un’angolazione diversa. Per quanto è noto, come stile semimonitor di cima di costruzione la parte della casa sotto il versante anteriore è molti piedi più bassa di quella sotto il versante posteriore del tetto, per permettere di porre delle finestre nello spazio perpendicolare sopra al tetto più basso, per la migliore illuminazione e ventilazione della parte posteriore della casa. L’occasione per introdurre tali caratteristiche di solito indica difetto nel disegno generale della struttura. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

Walls. Walls of structures for poultry should always be perpendicular. This applies to every form and size of house or coop designed for poultry. Whatever may be tolerated in a converted coop or building, the walls of one designed for poultry should be perpendicular. When one function of the glass window was to warm the interior of a closed building by the sun, houses were built with sloping front walls, in order that the windows might be placed at the angle that would make them most effective for that purpose. This form of construction was unsatisfactory, even when it had supposed advantages. |

Muri . I muri di strutture per pollame dovrebbero sempre essere perpendicolari. Questo si applica a ogni forma e dimensione di casa o pollaio progettati per il pollame. Qualunque cosa può essere tollerata in un pollaio o edificio convertito, i muri di ognuno progettato per il pollame dovrebbero essere perpendicolari. Quando una funzione della finestra di vetro era di scaldare col sole l'interno di un edificio chiuso, furono costruite case con muri anteriori inclinati, in modo che le finestre potessero essere messe con un angolo che le renderebbe più efficaci a tale scopo. Questa forma di costruzione era insoddisfacente, anche quando aveva fatto supporre dei vantaggi. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

Floors. Within the same walls and under the same roof, floors should be on the same level. They are always made so in small buildings, but when long houses are placed on ground which slopes with the length of the house, builders sometimes make a building with roof following the slope [126] of the land. This may not be a serious fault if there are tight cross partitions at short distances,* but if the length of the space between close division walls is greater than about thirty feet, there is likely to be a quite marked difference in temperature between the higher and lower ends, and drafty conditions on that account. The exterior of such a building is unsightly. When the ground is so uneven, the best way is to make a series of sections on different levels, each higher section one or two steps above the next lower one, the length of the sections to be determined by the grade. |

Pavimenti . All'interno degli stessi muri e sotto lo stesso tetto i pavimenti dovrebbero essere allo stesso livello. Sono fatti sempre così nei piccoli edifici, ma quando case lunghe sono messe su terra che si inclina con la lunghezza della casa, i costruttori qualche volta fanno un edificio con tetto che segue il pendio del suolo. Questo può non essere un errore serio se ci sono strette sezioni oblique a brevi distanze,* ma se la lunghezza dello spazio tra vicini muri di divisione è più grande di circa 30 piedi, c'è probabilmente una differenza piuttosto marcata in temperatura tra le estremità più alte e più basse, e le condizioni ventose su quel reparto. L'esterno di un tale edificio è brutto. Quando la terra è così disuguale, il modo migliore è fare una serie di sezioni su livelli diversi, ogni sezione più alta 1 o 2 passi sopra al prossimo più basso, la lunghezza delle sezioni deve essere determinata dal gradino. |

|||

|

* I have seen long nursery brooder houses for ducklings with floor following the slope of the land, that seemed to work well without partitions, but these were artificially heated, and the partitions between pens were much higher than the height of the ducklings. |

* Io ho visto lunghe case di chiocce per piccoli anatroccoli con pavimento che segue il pendio del suolo, che sembravano lavorare bene senza sezioni, ma queste erano artificialmente scaldate, e le sezioni tra recinti erano molto più alte dell'altezza degli anatroccoli. |

|||

|

Eccentric features in poultry houses and coops are to be avoided. As a rule, the plainest, simplest style of structure that will answer the purpose gives best general satisfaction. Exterior features designed to give special adjustments of a coop or house to a variety of conditions are often objectionable because of the attention that they require. Elaborate interior arrangements designed to save labor rarely accomplish that object. Extra features, outside or inside, add greatly to the original outlay for equipment, and to the amount of investment on which interest, taxes, etc. must be earned before actual revenue is obtained. With capital limited, as it usually is, it is much better policy to cut out all unnecessary features and to save as much as possible for stock and for working capital. One of the most common mistakes in poultry keeping is that of putting so much of the available capital into buildings that the poultryman is hampered for a long time for money for other expenses. |

In case per pollame e nei pollai le caratteristiche eccentriche devono essere evitate . Come regola, il più facile, il più semplice stile di struttura che risponderà allo scopo dà la migliore soddisfazione generale. Caratteristiche esterne ideate per dare adattamenti speciali di un pollaio o casa a una varietà di condizioni sono spesso deplorevoli a causa dell'attenzione che richiedono. Elaborate sistemazioni interne progettate per salvare lavoro raramente realizzano quello scopo. Caratteristiche addizionali, esterne o interne, si aggiungono grandemente alla spesa originale per l’attrezzatura, e all'ammontare di investimento sul quale si devono guadagnare interesse, tasse, ecc. prima che sia ottenuto il reddito attuale. Con un capitale limitato, come di solito è, la molto migliore linea di condotta è tagliare tutte le caratteristiche non necessarie e salvare il più possibile per partita e per capitale di lavoro. Uno degli errori più comuni nell’allevare pollame è quello di mettere così tanto del capitale disponibile in edifici che l’avicoltore è impedito per molto tempo ad avere soldi per altre spese. |

|||

|

Materials used for poultry structures. Wood is more extensively used than all other materials combined. Nearly all movable buildings and coops are made of wood, and it is the principal material in most of the larger structures. When it is desired to make the cost of construction as low as possible, and a tight construction is necessary, the cheapest of lumber is used, and the inside of the building covered with a substantial roofing paper. If it is not necessary to have tight walls and roof, a grade of boards as much better as the builder desires may be used. With common boards this gives the cheapest construction. Shingles were formerly used [127] very extensively to cover sides as well as roofs of poultry buildings, but as they have steadily risen in price and gone down in quality, while the quality of roofing paper has greatly improved, shingles are now little used, except when conformity to surrounding buildings requires it. |

Materiali usati per le strutture per il pollame . Il legno è usato più estesamente rispetto a tutti gli altri materiali messi insieme. Quasi tutti gli edifici movibili e i pollai sono fatti di legno, che è il materiale principale nella maggior parte delle strutture più grandi. Quando si desidera rendere il costo di una costruzione il più basso possibile, ed è necessaria una costruzione solida, è usato il legname più economico, e l'interno dell'edificio coperto con una consistente carta di copertura. Se non è necessario avere muri solidi e un tetto, può essere usata una varietà di assi tanto migliori come il costruttore desidera. Con assi comuni si ottiene la costruzione più economica. Assicelle furono precedentemente usate molto abbondantemente per coprire lati come pure tetti di edifici per pollame, ma siccome sono cresciute intensamente di prezzo e diminuite in qualità, mentre la qualità di carta di copertura è grandemente migliorata, ora le assicelle sono usate poco, eccetto quando lo richiede una conformità con edifici circostanti. |

|||

|

The extensive use of wood for buildings for poultry comes about because it is usually the cheapest available material, and because it is material in which almost every poultry keeper who wishes to build his own buildings can work. Any material used for other buildings may be used: iron, stone, brick, clay, cement, are all used occasionally for poultry houses. As a rule these are more economical than wood only when they can be had very cheap or the poultryman is expert in working in them. |

L'uso esteso del legno per edifici per pollame avviene perché di solito è il materiale disponibile più economico, e perché è un materiale col quale può lavorare quasi ogni allevatore di pollame che desidera costruire i suoi edifici. Qualunque materiale usato per altri edifici può essere usato: ferro, pietra, mattone, argilla, cemento, sono tutti usati di quando in quando per case di pollame. Come regola questi sono più economici del legno solo quando possono essere ottenuti a prezzo molto basso o se l’avicoltore è esperto nel lavorare con essi. |

|||

|

Glass is used only as necessary to give light when doors and curtains are closed. For many years it was the practice to use as much glass as possible, in order to heat the house through the windows when the sun shone. With the introduction of fresh-air types of houses the area of glass used has been reduced, and sometimes glass has been discarded for cotton cloth or burlap. |

Il vetro è usato solo come necessario per dare luce quando le porte e le tende sono chiuse. Per molti anni fu una pratica usare il più vetro possibile per scaldare la casa attraverso le finestre quando il sole risplendeva. Con l'introduzione dei tipi di case con aria fresca l'area di vetro usata è stata ridotta, e qualche volta il vetro è stato scartato per stoffa di cotone o tela ruvida. |

|||

|

Cotton cloth is extensively used in both door and window openings. Its use depends primarily on its porosity: it admits air. With a sufficient area of cloth to give what light is required on dull days with all openings closed, no glass is needed. The relative amounts of glass and cloth to be used must be determined according to the design of the house and local conditions. |

Stoffa di cotone è estesamente usata nelle aperture di porta e di finestra. Il suo uso dipende innanzitutto dalla sua porosità: lascia passare aria. Con un'area sufficiente di stoffa per dare la luce che è richiesta nei giorni uggiosi con tutte le aperture chiuse, nessun vetro è necessario. Le relative quantità di vetro e stoffa da essere usate devono essere determinate secondo lo scopo della casa e le condizioni locali. |

|||

|

Floor materials . Wherever the soil is of suitable character (sand or loam, or a mixture of the two), and drainage such that it can be kept in good condition, an earth floor is the best for all poultry buildings. Where drainage is defective or the soil contains much clay, movable structures should have floors of wood, and permanent structures floors of wood or cement. |

Materiali per il pavimento . Dovunque il suolo è di carattere adeguato (sabbia o argilla, o una miscela delle due), e uno scarico delle acque tale che può essere tenuto in buona condizione, un pavimento di terra è il meglio per tutti gli edifici per pollame. Dove lo scarico delle acque è difettoso o il suolo contiene molta creta, strutture mobili dovrebbero avere pavimenti di legno, e le strutture permanenti dei pavimenti in legno o cemento. |

|||

|

Quality of construction. The question of durability is of less importance in the construction of poultry coops and buildings than in most other lines of construction. Movable structures of any size must be strong enough to stand the handling and moving to which they are subjected. Permanent buildings, being nearly all low, one-story buildings, may be of very light construction, as will be shown in illustrations. All that is necessary is that there shall be [128] frame enough to hold the shell firmly, that it be securely nailed, and that the sills shall be either so placed or protected that they will not rot, or put in so that when decayed they may be easily replaced. Some of the most practical poultrymen put sills right on the earth and replace them when necessary, finding it cheaper in the long run to do this in buildings of light construction than to use heavy sills and protect them to prevent the decay of the wood. |

Qualità della costruzione . La questione della durabilità è di minore importanza nella costruzione di stie ed edifici per pollame rispetto a molti altri settori di costruzione. Strutture mobili di qualsiasi dimensione devono essere forti abbastanza per sostenere il maneggio e il movimento ai quali sono sottoposte. Edifici permanenti, essendo quasi tutti bassi, edifici di un piano, possono essere di costruzione molto leggera, come sarà mostrato nelle illustrazioni. Tutto quello che è necessario è che vi sia intelaiatura sufficiente per tenere saldamente l’involucro, che sia inchiodato con sicurezza, e che le soglie saranno messe o protette in modo tale che non si decomporranno, o messe in modo tale che quando deteriorate possono essere facilmente sostituite. Qualcuno degli avicoltori più pratici mettono soglie diritte sulla terra e le sostituiscono quando necessario, trovando più conveniente nel lungo andare fare questo in edifici di costruzione leggera che usare soglie pesanti e proteggerle per prevenire il decadimento del legno. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

Durability has to be considered most in connection with materials which are shorter-lived than wood, and with parts that receive wear. When roofing paper is used for covering, it is economical to use paper of good quality that with proper care may be expected to last from fifteen to twenty years. Cloth is now often preferred to glass for openings, because it is cheaper and admits some air; but cloth or like porous material is so short-lived, when exposed to the weather, that in the long run it may be cheaper to use glass and leave windows partly open, as we do in our dwellings. If cement floors are used they should be substantially built; a common mistake is to make them too thin and with an insufficient foundation. Such floors crack and settle and become uneven and very unsatisfactory, and the faults cannot be remedied except by taking off the old cement and remaking the floor. |

La durabilità deve essere considerata per lo più in relazione con materiali che hanno vita più breve rispetto al legno, e con parti che ricevono usura. Quando è usata carta di copertura per coprire, è economico usare carta di buona qualità che con una cura corretta ci si può aspettare che duri da 15 a 20 anni. La stoffa è ora spesso preferita al vetro per le aperture, perché è più conveniente e lascia entrare un po’ d’aria; ma la stoffa o materiale poroso similare hanno vita così breve quando esposti al maltempo che a lungo andare può essere più conveniente usare il vetro e lasciare le finestre in parte apre, come noi facciamo nelle nostre abitazioni. Se sono usati pavimenti di cemento dovrebbero essere costruiti solidi; un errore comune è farli troppo sottili e con una fondamento insufficiente. Tali pavimenti si rompono e si avvallano e diventano irregolari e molto insoddisfacenti, e i difetti possono essere rimediati solo togliendo il vecchio cemento e rifacendo il pavimento. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

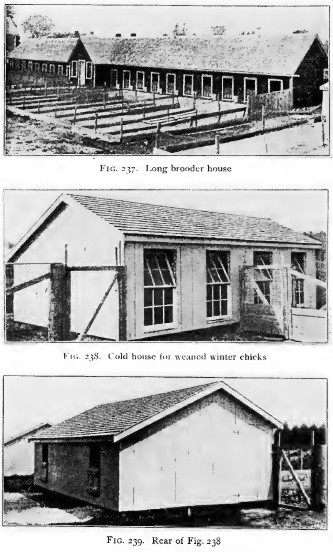

Warmth is not given such consideration as formerly in the construction of houses for adult and weaned birds, but in building incubator and brooder houses, or other special buildings which are to [129] be heated, it is necessary to use double walls. For open-front or fresh-air houses all that is necessary is to make the roof, back, and ends wind- and rain-proof. The front need not be of tight construction; indeed, it has not been shown that, for birds not easily affected by frost, there is any advantage in making the house with perfectly tight roof, back, and ends. On the whole, the present tendency is to make all kinds and sizes of structures for poultry of the lightest construction that will serve. |

Il calore non è dotato di tale considerazione come in precedenza nella costruzione di case per uccelli adulti e svezzati, bensì, nel costruire case per incubatrice e chioccia, o altri edifici speciali che devono essere scaldati, è necessario usare muri doppi. Per case con facciata aperta o con aria fresca tutto ciò che è necessario è fare il tetto, il retro, le parti terminali a prova di vento e pioggia. La facciata deve essere di costruzione stretta; effettivamente, non è stato dimostrato che, per uccelli non colpiti facilmente dal gelo, c’è parecchio vantaggio nel fare la casa con tetto, retro e parti finali perfettamente chiusi. Complessivamente, la tendenza attuale è costituire tutti i tipi e dimensioni di strutture per pollame con la costruzione più leggera che servirà. |

|||

|