Principles

and practice of poultry culture – 1912

John Henry Robinson (1863-1935)

Principi

e pratica di pollicoltura – 1912

di John Henry Robinson (1863-1935)

Trascrizione e traduzione di Elio Corti![]()

2016

Traduzione assai difficile - spesso incomprensibile

{} cancellazione – <>

aggiunta oppure correzione

CAPITOLO XIV

|

[238] CHAPTER XIV |

CAPITOLO XIV |

||

|

INCUBATION |

INCUBAZIONE |

||

|

Incubation the beginning and the end of the common cycle of operations in poultry culture. By incubation the bird is produced from the egg. For incubation and the perpetuation of its kind the bird, according to its sex, produces eggs or contributes to their fertilization; and then, in birds of the air, both male and female take part in the incubating of the eggs, the substance of which has been furnished almost wholly by the female. With poultry in domestication, as shown in Chapter I, the male has no part in incubation, and the female may often be relieved of it to the very great economic advantage of man; but, whatever the attitude of the poultryman toward the process, incubation is one of his most perplexing problems, affecting and affected by many other important problems, and seldom presenting itself in the same form twice in succession. From the nature of the subject its proper place in a systematic study of poultry culture is doubtful. Equally good reasons may be given for beginning and for concluding a detailed description of a generation of birds with the subject of incubation. But, considering the close analogy between the egg of an oviparous creature and the seed of a plant, it seems most natural and appropriate to begin a practical study of those details with the egg considered simply as material for the purpose, and without regard to either its antecedents or its possibilities beyond the mere production of an organism of the kind which produced it. |

L’incubazione, l'inizio e la fine del ciclo comune di operazioni nell’allevamento del pollame . Con l’incubazione l'uccello è prodotto dall'uovo. Per l'incubazione e la perpetuazione del suo genere l'uccello, a seconda del suo sesso, produce uova o contribuisce alla loro fecondazione; e poi, in uccelli che frequentano l'aria, sia il maschio che la femmina prendono parte all’incubazione delle uova, la cui sostanza è stata fornita quasi completamente dalla femmina. Nel pollame addomesticato, come affermato nel 1° capitolo, il maschio non partecipa all’incubazione, e la femmina può spesso esserne svincolata con un vantaggio economico molto grande per l’uomo; ma, qualunque sia l'atteggiamento dell’avicoltore verso il procedimento, l'incubazione è uno dei suoi problemi più imbarazzanti, che colpisce e che è colpito da molti altri importanti problemi, e raramente presentandosi nella stessa forma 2 volte in successione. In base alla natura del soggetto, il suo luogo esatto in un studio sistematico di pollicoltura è dubbioso. Ragioni ugualmente buone possono essere date per cominciare e per concludere una descrizione dettagliata di una generazione di uccelli col soggetto dell'incubazione. Ma, in considerazione della stretta analogia tra l'uovo di una creatura ovipara e il seme di una pianta, sembra molto naturale e appropriato cominciare un studio pratico di quei dettagli con l'uovo considerato semplicemente come materiale per lo scopo, e senza riguardo sia ai suoi antecedenti che alle sue possibilità oltre la mera produzione di un organismo del tipo di quello che lo produsse. |

||

|

The egg. Considered from the point of view just indicated, an egg consists of four parts: |

L'uovo . Considerato dal punto di vista appena indicato, un uovo consiste di 4 parti: |

||

|

1. A germ, which is the true egg. |

1. Un germe, che è il vero uovo. |

||

|

2. A mass of albumin (the white of the egg), ― nitrogenous matter which the germ, quickened into life, will, as it grows, appropriate to form the substance of the embryonic being. |

2. Una massa di albumina (il bianco dell'uovo) ― materia azotata che il germe, accelerato nel processo vitale, vuole, crescendo, appropriata per formare la sostanza dell'essere embrionale. |

||

|

3. A supply of food (the yolk of the egg) for the first nourishment of the young bird after exclusion. |

3. Un rifornimento di cibo (il tuorlo dell'uovo) per il primo nutrimento del giovane uccello dopo la schiusa. |

||

|

[239] 4. A protective covering which is composed of a double membrane within a hard shell. |

4. Una copertura protettiva che è composta da una doppia membrana all'interno di un guscio duro. |

||

|

The germ may be seen, when the egg is broken, as a little white speck on the yolk, and always on the upper side of the yolk, which position it keeps because the yolk is suspended in the white by two albuminous strings, and in whatever position the egg may lie, the yolk turns, bringing the germ to the upper side. |

Il germe può essere visto, quando l'uovo è rotto, come una macchiolina bianca sul tuorlo, e sempre sul lato superiore del tuorlo, posizione che mantiene perché il tuorlo è sospeso nel bianco da 2 sequenze di cordoncini albuminosi, e in qualunque posizione l'uovo giaccia, il tuorlo gira, portando il germe verso il lato superiore. |

||

|

Note. An egg as described may be produced by the female bird without association with the male. In the ordinary natural course the female on arriving at maturity (or at the breeding season) produces eggs which are complete for commercial purposes and also, as far as her contribution to the egg goes, for breeding purposes; but the egg will not hatch unless the germ furnished by the female has been fertilized by union with the sperm contributed by the male at the proper stage of its development, nor will the germ thus fertilized produce a creature of sufficient vitality for normal development if the germinal elements contributed by the parents are lacking in vitality. Just how far a superabundance of vitality contributed by one parent may compensate for a deficiency in vitality in the contribution of the other is not known. That there is a tendency to equalization is often apparent, yet it is just as evident that there must be a certain degree of initial vitality in an element before it can unite with its opposite sexual element for the production of a new organism. This is illustrated best in the case of those hens of great laying capacity which produce few or no chicks, their eggs rarely becoming fertile even with every opportunity to do so. The fact that a hen can produce, in extraordinary numbers, eggs each of which apparently furnishes the material for a chick, though the accompanying germ lacks the vitality which would enable it under proper conditions to utilize that material, indicates that capacity to transmit vitality is more restricted than capacity to produce material for the building of new organisms. Of like significance in this connection is the fact that, though the male's contribution to the egg is but a minute quantity of sperm, the capacity of the average male to "strongly fertilize" eggs is plainly limited. These points are considered more fully in the chapters relating to breeding. Mention is made of them here to show that, in the nature of the case, the ordinary lot of eggs used for incubation is unlikely to be high in "hatchability," ― which fact must be given due consideration in every effort to estimate causes of unsatisfactory hatches. |

Nota. Un uovo come descritto può essere prodotto dall'uccello femmina senza un rapporto col maschio. Nel corso naturale ordinario la femmina, arrivando alla maturità (o al periodo della riproduzione), produce uova che sono complete per scopi commerciali e anche, per quanto concerne il suo contributo all'uovo, per scopi riproduttivi; ma l'uovo non schiuderà se il germe fornito dalla femmina non è stato fertilizzato dall’unione con lo sperma fornito dal maschio in un giusto stadio del suo sviluppo, né il germe così fertilizzato produrrà una creatura di sufficiente vitalità per uno sviluppo normale se gli elementi germinali forniti dai genitori mancano in vitalità. Proprio non si sa fino a che punto una sovrabbondanza di vitalità fornita da un genitore può compensare una deficienza in vitalità fornita dall'altro. Che ci sia una tendenza al pareggiamento è spesso evidente, ed è così evidente che in un elemento ci deve essere un certo grado della vitalità iniziale prima che possa unirsi col suo opposto elemento sessuale per la produzione di un nuovo organismo. Ciò è meglio illustrato nel caso di quelle galline di grande capacità depositiva che producono pochi o nessun pulcino, le loro uova diventando raramente fertili anche con ogni opportunità di farlo. Il fatto che una gallina può produrre uova in numeri straordinari, ognuno delle quali apparentemente fornisce il materiale per un pulcino, sebbene il germe che l’accompagna manchi della vitalità che in corrette condizioni lo metterebbe in grado di utilizzare quel materiale, indica che quella capacità di trasmettere la vitalità è più ristretta della capacità di produrre materiale per la realizzazione di nuovi organismi. Di pari significato in questo collegamento è il fatto che, sebbene il contributo del maschio all'uovo è solo una piccola quantità di sperma, la capacità del maschio comune di "fertilizzare fortemente" le uova è chiaramente limitata. Questi punti sono considerati più pienamente nei capitoli relativi alla riproduzione. Menzione qui ne è fatta per mostrare che, nella natura del caso, la partita ordinaria delle uova usate per l'incubazione è improbabile che sia alta in "capacità di schiusa" ― fatto che deve essere tenuto in dovuta considerazione in ogni sforzo di valutare le cause di schiuse insoddisfacenti. |

||

|

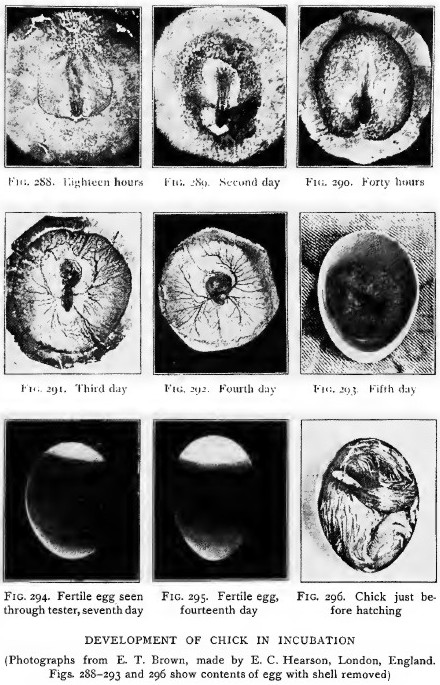

A fertile egg. Technically, a fertile egg is an egg which has fertilized germs possessed of sufficient vitality to develop so far that development can be seen through the shell when the egg, after having been incubated for a time, is tested by being held before a light in the usual way. Fertility cannot be determined without incubation. The amount of incubation necessary to show whether [240] an egg is fertile varies with the vitality of the germ, the color and texture of the shell of the egg, and the intensity of the light before which it is observed. A thin-shelled white egg in a strong light may show fertility inside of twenty-four hours. A dark-shelled egg, weak in fertility, tested in a poor light, may appear doubtful after a week of incubation. Ordinarily tests made at the fifth to the seventh day give an experienced operator reliable indications of the fertility and vitality of eggs that have been incubated under proper conditions. Though not invariable, it is the general rule that the fertility of eggs from a mating is quite constant through a season; so that when the degree of fertility of eggs from a pen, flock, or stock is once found, it is likely to be maintained for some time. |

Un uovo fertile . Tecnicamente, un uovo fertile è un uovo che ha germi fertilizzati provvisti di sufficiente vitalità per svilupparsi quel tanto che lo sviluppo può essere visto attraverso il guscio quando l'uovo, dopo essere stato incubato per un certo tempo, è esaminato tenendolo davanti a una luce nel solito modo. La fertilità non può essere determinata senza l'incubazione. L'ammontare di incubazione necessaria per mostrare se un uovo è fertile varia con la vitalità del germe, del colore e della trama del guscio dell'uovo, e l'intensità della luce di fronte alla quale è osservato. Un uovo bianco e dal guscio sottile di fronte a una luce forte può mostrare la fertilità entro 24 ore. Un uovo dal guscio scuro, debole in fertilità, esaminato con una povera luce, può apparire dubbioso dopo una settimana d'incubazione. Abitualmente le prove fatte dal 5° al 7° giorno danno a un operatore esperto le attendibili indicazioni sulla fertilità e vitalità di uova che sono state incubate in corrette condizioni. Sebbene non invariabile, è una regola generale che la fertilità di uova prodotte con un accoppiamento è piuttosto costante durante una stagione; quindi quando il grado di fertilità di uova da un recinto, stormo, o gruppo è rinvenuta una volta, probabilmente si manterrà per qualche tempo. |

||

|

As a rule, fertility and vitality reach their highest point of combination at the natural hatching season. Fertility is lowest and vitality highest in advance of this season, and fertility highest and vitality lowest after it; but numerous special cases furnish exceptions to these general conditions. Fertile, hatchable eggs are the prime factor in incubation, and a knowledge of the hatching properties of the eggs used is absolutely necessary for intelligent judgment of other factors when hatches are unsatisfactory. Self-evident as this seems when stated, a great deal of work in incubation is done without this basic knowledge, the operator working quite in the dark. Detailed instructions as to determination of fertility are given in the paragraphs relating to the operation of incubators. |

Come regola, la fertilità e la vitalità raggiungono il loro punto più alto di associazione nella stagione naturale di schiusa. La fertilità è più bassa e la vitalità più alta con l’avanzare di questa stagione, e la fertilità più alta e la vitalità più bassa dopo di essa; ma numerosi casi speciali forniscono eccezioni a queste condizioni generali. Uova fertili, schiudibili, sono il principale fattore nell’incubazione, e una conoscenza delle proprietà di schiusa delle uova usate è assolutamente necessaria per un giudizio intelligente su altri fattori quando le schiuse sono insoddisfacenti. Ovvio come questo sembra quando stabilito, molto lavoro di incubazione è svolto senza questa cognizione elementare, dato che l'operatore lavora completamente al buio. Istruzioni particolareggiate come per la determinazione della fertilità sono date nei paragrafi relativi al funzionamento delle incubatrici. |

||

|

Heat the energetic factor in incubation. Given a hatchable egg, the continuous application of a proper degree of heat for a definite period of time, varying in different kinds of birds, will produce an embryonic bird which, when it has attained the fullest possible development within the shell, will break the shell and emerge from it. In nature the heat for incubation is usually applied by the bird which laid the egg, relieved at intervals, perhaps, by its mate. In artificial incubation, oil, coal, gas, and electricity are used. The source of heat, however, is immaterial. All that is necessary is that the proper degree of heat be continuously maintained (not absolutely, but approximately) for the required time, under such circumstances that atmospheric conditions affecting the development of the embryo within the egg will not be markedly unfavorable. |

Il caldo, fattore energetico nell’incubazione . Con un uovo schiudibile, la continua applicazione di un corretto grado di calore per un periodo di tempo definito, che varia in generi diversi di uccelli, produrrà un uccello embrionale che, quando ha raggiunto il più pieno sviluppo possibile all'interno del guscio, romperà il guscio e ne uscirà. In natura il calore per l'incubazione di solito è applicato dall'uccello che ha deposto l'uovo, forse aiutato a intervalli dal suo compagno. Nell’incubazione artificiale sono usati petrolio, carbone, gas ed elettricità. Tuttavia, la fonte di calore è indifferente. Tutto ciò che è necessario è che il grado corretto di calore sia mantenuto continuamente (non in modo assoluto, ma all’incirca) per il tempo richiesto, in circostanze tali che le condizioni atmosferiche che influiscono sullo sviluppo dell'embrione all'interno dell'uovo non saranno marcatamente sfavorevoli. |

||

|

[241] The fact that, in natural incubation, eggs seem to hatch equally well under very different atmospheric conditions indicates that as close adjustments of ventilation and moisture as of heat are not required, ― that within limits (not definitely ascertained) these may vary considerably without materially affecting the hatch. The normal temperature of fowls is about 106°, of other poultry about the same. The temperature in natural incubation, therefore, would be a few degrees lower, or the temperature at which eggs could be kept with a body at about 106°, applying heat from one side only. The usual temperature of eggs under hens has been found to be from 102° to 104°, with a mean of 103°. |

Il fatto che, nell’incubazione naturale, le uova sembrano schiudere ugualmente bene in condizioni atmosferiche molto diverse, indica che stretti adattamenti di ventilazione e umidità come pure di calore non sono richiesti ― che entro certi limiti (non definitivamente accertati) possono variare notevolmente senza colpire materialmente la schiusa. La temperatura normale dei polli è circa 106°, circa la stessa in altro pollame. Quindi la temperatura nell’incubazione naturale sarebbe di pochi gradi meno, o la temperatura alla quale le uova potrebbero essere mantenute con un corpo a circa 106°, applicando calore da un solo lato. La temperatura abituale delle uova sotto le galline è stata trovata essere da 102° a 104°, con una media di 103°. |

||

|

Antiquity of artificial methods. Artificial incubation has been practiced by the Egyptians and Chinese for some thousands of years. As developed by these peoples the appliances are crude and the success of the process depends largely upon the judgment, skill, and careful attention of the operator. Knowledge of the art is confined principally to families in which it has been handed down from generation to generation. Operations are on an extensive scale, and the operator remains with, and sometimes in, the "incubator" continuously throughout a period of incubation. Modern artificial incubation as developed in America and Europe is on different lines. The constant effort of the occidental inventor has been to devise an incubator that might be operated by any one anywhere, on any desired scale, and with the least possible personal attention. |

L'antichità di metodi artificiali . L'incubazione artificiale è stata praticata dagli Egiziani e dai Cinesi per alcune migliaia di anni. Come sviluppati da questi popoli gli apparecchi sono rozzi e il successo del processo dipende grandemente sul giudizio, l'abilità e l’accurata attenzione dell'operatore. La conoscenza dell'arte è confinata principalmente in famiglie cui è stata trasmessa di generazione in generazione. Le operazioni sono su una gamma estesa, e l'operatore rimane con, e qualche volta nell’"incubatrice", continuamente per tutto il periodo dell'incubazione. L’incubazione artificiale moderna, come sviluppata in America ed Europa, si basa su metodi diversi. Lo sforzo continuo dell'inventore occidentale è stato concepire un'incubatrice che possa essere gestita ovunque da chiunque, su ogni gamma desiderata, e con la possibile minima attenzione personale. |

||

|

The problem in artificial incubation. To maintain a temperature of approximately 103°, with suitable atmospheric conditions, ― to duplicate, as nearly as possible, in an artificially heated chamber, the conditions to which an egg incubated by a bird is subjected, ― is the incubator operator's problem. This problem presents two phases. The first of these, the designing and construction of incubators, is a matter for the inventor and manufacturer, and does not directly interest the ordinary student. |

Il problema nell’incubazione artificiale . Mantenere una temperatura di circa 103°, con condizioni atmosferiche appropriate ― duplicare, il più possibile, in una camera scaldata artificialmente, le condizioni alle quali è sottoposto un uovo incubato da un uccello ― è il problema dell'operatore dell’incubatrice. Questo problema presenta 2 fasi. La prima, la progettazione e la costruzione di incubatrici, è una materia per l'inventore e il fabbricante, e non interessa direttamente lo scolaro ordinario. |

||

|

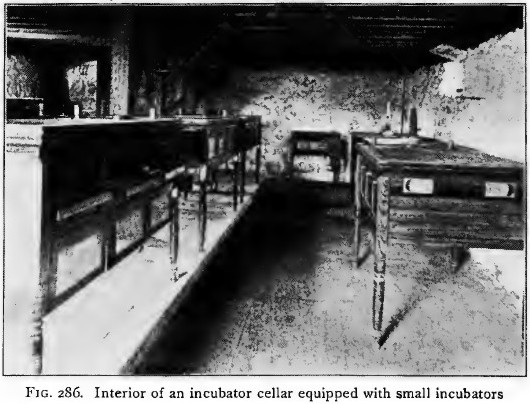

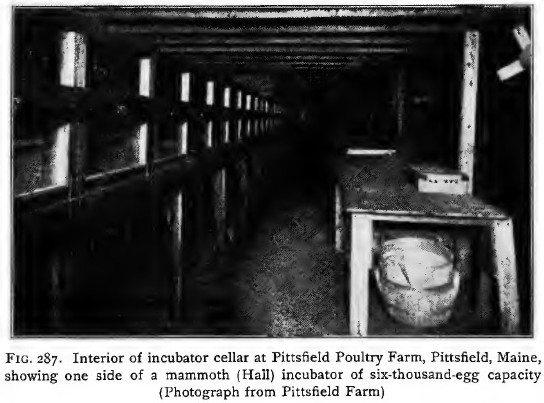

The individual poultryman’s problem in artificial incubation is to take a "machine" which, when properly attended, is self-regulating for heat, give it the attention requisite for this, and adapt ventilation and moisture to local atmospheric conditions. To reduce to the minimum the variations in these conditions, the [242] incubator is usually placed in a basement room or in a cellar. Under the most skillful management, results in artificial incubation are likely to be more variable than when eggs of like hatching quality are incubated with equal care by natural methods, because the judgment of a man guided by experience and observation works less accurately in such matters than the inclination of the bird guided by instinct and sensation. |

Il problema individuale dell’avicoltore nell’incubazione artificiale è di prendere una "macchina" che, quando propriamente gestita, è auto regolatrice per il calore, fornisce l'attenzione richiesta in merito, e adatta ventilazione e umidità alle condizioni atmosferiche locali. Per ridurre al minimo le variazioni di queste condizioni, l’incubatrice è di solito messa in una stanza seminterrata o in una cantina. Sotto la più abile gestione, i risultati dell’incubazione artificiale è probabile che siano più variabili di quando le uova di uguali qualità di schiusa sono incubate con uguale cura da metodi naturali, perché il giudizio di un uomo guidato da esperienza e osservazione lavora meno accuratamente su tali situazioni rispetto all'inclinazione dell'uccello guidato dall’istinto e dalla sensibilità. |

||

|

Experience and skill count in the operation of incubators, as in all things, but the incubator operator has a slightly different problem in every machine that he uses, and a new problem in every hatch, and a high degree of efficiency in this line of work is only attained by careful study of the behavior of machines in the positions in which they are placed, and by such close attention to the lamp, or other source of heat, that the eggs are never subjected to injurious temperatures. |

Esperienza e abilità contano nella gestione delle incubatrici, come in tutte le cose, ma l'operatore di incubatrice ha un problema lievemente diverso in ogni macchina che usa, e un problema nuovo in ogni schiusa, e un alto grado di efficienza in questa linea di lavoro è raggiunta solo da uno studio accurato del comportamento di macchine nelle posizioni in cui sono messe, e da un’attenzione così vicina alla lampada, o altra fonte di calore, in modo che le uova non sono mai sottoposte a temperature dannose. |

||

|

Value of both methods of incubation. When incubators were perfected to the point where temperature was easily controlled, there was a general tendency to substitute the artificial for the natural method. As it became generally known that, notwithstanding the progress made, the artificial hatchers had their faults and limitations, and still required close attention on the part of the operator, this tendency was checked. It is now generally recognized that the natural method is the better method for the great majority of poultry keepers, provided they can get birds to incubate when they need them, but that whenever the natural method is for any reason inadequate, the artificial hatcher must be used. On this principle one or more incubators (of suitable capacity) and the necessary brooders become a part of the equipment of most poultry keepers, to be used in emergencies and for special purposes, even though hatching is done mostly by the natural method; and whenever operations are on a large scale, incubators are relied upon to do the hatching, the only important exception to this being in the colony poultry-farming section of Rhode Island. |

Valore di ambedue i metodi d'incubazione . Quando le incubatrici furono perfezionate al punto in cui la temperatura era facilmente controllata, c'era una tendenza generale a sostituire il metodo naturale con quello artificiale. Come venne generalmente riconosciuto, nonostante il progresso fatto, le incubatrici artificiali avevano le loro colpe e limitazioni, e richiedevano ancora una stretta attenzione da parte dell'operatore, e questa tendenza era esaminata. Ora è generalmente riconosciuto che il metodo naturale è il metodo migliore per la grande maggioranza di allevatori di pollame, purché possano trovare uccelli per incubare quando li hanno bisogno, ma che ogni qualvolta il metodo naturale è per qualche ragione inadeguato, devono essere usati le incubatrici artificiali. In base a questo principio una o più incubatrici (di adeguata capacità) e le chiocce necessarie divennero una parte dell'attrezzatura di molti allevatori di pollame, per essere usate in emergenze e per scopi speciali, anche se il covare è attuato sopratutto dal metodo naturale; e ogni qualvolta le operazioni sono su larga scala, le incubatrici hanno la fiducia di attuare la schiusa, l'unica importante eccezione a ciò trovandosi nella sezione della colonia che alleva pollame nel Rhode Island. |

||

|

Hatching by Natural Methods |

Covare con metodi naturali |

||

|

Broodiness. The inclination to incubate is a normal character in birds, which in some races and stocks has wholly or partly disappeared. The length of the period of laying, before broodiness, [243] varies greatly. Some hens will become broody after laying only six or seven eggs. Usually hens of stock strongly inclined to broodiness will lay from one to two dozen eggs before becoming broody. In strains or stocks in which the broody habit is present, but not strongly established, hens often lay for two, three, or even five or six months without becoming broody. As a rule, increased egg production is accompanied by decrease in broodiness. Among ducks the Pekin and Indian Runner are mostly nonsitters. In geese, turkeys, and the less common kinds of poultry broodiness is general. |

Disposizione alla cova . La propensione a covare è un carattere normale negli uccelli, che in alcune razze e gruppi è scomparso completamente o in parte. La lunghezza del periodo di deposizione, prima di mettersi a covare, varia parecchio. Alcune galline diverranno covatrici dopo aver deposto solo 6 o 7 uova. Di solito le galline di gruppi fortemente propensi alla cova deporranno da 1 a 2 dozzine di uova prima di mettersi a covare. In razze o gruppi in cui è presente l'abitudine di covare, ma non fortemente fissata, le galline spesso depongono per 2, 3 o anche 5 o 6 mesi senza diventare covatrici. Come regola, l’aumentata produzione di uova è accompagnata da un calo della propensione a covare. Fra le anatre la Pechino e la Corritrice Indiana sono soprattutto delle non covatrici. In oche, tacchini, e nei generi meno comuni di pollame, la propensione a covare è generale. |

||

|

Broodiness is shown first in the inclination of the bird to remain on the nest after laying, then by a change of attitude toward the keeper, and by a change of voice. Usually birds, unless very tame, are shy about being approached on the nest, and leave it if molested. The broody bird in most cases becomes bold, sometimes vicious, and even if she will not allow herself to be handled on the nest, will plainly show as much anger as fear when molested. Hens and other gallinaceous poultry, when broody, make a clucking noise, which is obviously meant to guide the young and keep them from scattering too widely, and when disturbed give a harsh, warning cry. Female waterfowl, when broody, give a warning hiss, as the male is likely to do at any time when molested. The attitude and voice of the bird are surer indications of broodiness than her remaining on the nest, for sick birds frequently do that. |

La propensione a covare è esibita dapprima dall'inclinazione dell'uccello a rimanere sul nido dopo aver deposto, quindi da un cambio di atteggiamento verso l’allevatore, e da un cambio di voce. Di solito gli uccelli, a meno che siano molto domestici, sono timidi quando vengono avvicinati sul nido, e lo lasciano se molestati. L'uccello che cova in molti casi diventa audace, qualche volta vizioso, e anche se non permetterà di essere maneggiato sul nido, mostrerà chiaramente tanta rabbia quanta paura quando molestato. Galline e altro pollame gallinaceo, quando covano, fanno un rumore da chioccia, che evidentemente ha l’intenzione di guidare il giovane e non permettere loro di sparpagliarsi troppo estesamente, e quando disturbate emettono un grido aspro, ammonitore. Un uccello acquatico femmina, quando cova, dà un fischio di avvertimento, come è probabile che faccia il maschio sempre quando molestato. L'atteggiamento e la voce dell'uccello sono indicazioni più sicure di cova che il suo rimanere sul nido, in quanto uccelli disgustati frequentemente lo fanno. |

||

|

When broody hens are to be used for incubating, it is advisable to let them remain for several days on the nests that they have laid in, until broodiness becomes confirmed and they have ceased laying. The duration of broodiness is not (as is popularly supposed) determined or influenced by the time required to incubate the eggs of the bird. Unless broodiness is interrupted by a resumption of egg production, or she is compelled by exhaustion to leave the nest, a bird will remain on eggs until young appear, and may even keep for an indefinite time to a nest containing no eggs. |

Quando le galline che vogliono covare debbono essere usate per covare, è consigliabile permettere loro di rimanere per molti giorni sui nidi nei quali hanno deposto, finché la propensione a covare è confermata e hanno cessato di deporre. La durata del la propensione a covare non è (come generalmente ipotizzato) determinata o influenzata dal tempo richiesto per covare le uova dell'uccello. A meno che la propensione a covare venga interrotta da una ripresa della produzione di uova, o lui venga costretto da esaurimento a lasciare il nido, un uccello rimarrà sulle uova fino a quando il pulcino compare, e può anche rimanere per un tempo indefinito su un nido che non contiene uova. |

||

|

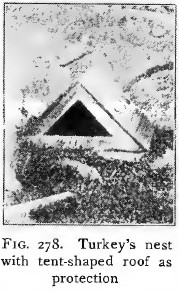

System in natural incubation. If more than two or three birds of any kind are set, arrangements for managing them should be systematized. A great deal of the dissatisfaction with natural methods of incubation is due to mismanagement. The sitting hens should always be separated from the rest of the flock and made as secure as possible from disturbing influences of all kinds; [244] yet they should be in a place convenient for the attendant to have oversight of them as he goes about his regular work. Most hens may be moved from their laying nests to any desired place, if moved after dark; many may be moved at any time. But the other kinds of poultry usually resent interference of this kind, and will incubate only in the nests in which they have been laying. For this reason it is customary, especially with turkeys and geese, before the birds begin to lay, to place, in locations attractive to them, nests that will be suitable for them during incubation. An empty barrel placed on its side in some partly secluded place is often used for both turkeys and geese. When the birds insist on making nests for themselves the careful keeper furnishes protection (see illustrations, p. 247) and, as far as the birds will tolerate it, tries to make them secure from molestation. |

Metodo nell’incubazione naturale . Se più di 2 o 3 uccelli di qualunque genere vengono collocati, le sistemazioni per gestirli dovrebbero essere sistematizzate. Molta insoddisfazione dei metodi naturali dell'incubazione è dovuta a una cattiva conduzione. Le galline che covano dovrebbero essere sempre separate dal resto del gruppo e rese il più sicure possibile da influenze inquietanti di ogni tipo; inoltre dovrebbero essere in un luogo per il custode conveniente a sorvegliarle quando fa il suo lavoro regolare. La maggior parte delle galline può essere spostata dai loro nidi di posa in qualunque altro luogo desiderato, se mosse quando fa buio; molte possono essere mosse in qualunque momento. Ma gli altri generi di pollame di solito risentono per le interferenze di questo tipo, e coveranno solo nei nidi in cui hanno deposto. Per questa ragione è consuetudine, specialmente con tacchini e oche, prima che gli uccelli comincino a deporre, mettere, in ubicazioni per loro attraenti, dei nidi che saranno per loro adatti durante l'incubazione. Un barile vuoto messo al loro posto in qualche luogo parzialmente appartato è spesso usato sia per tacchini che per oche. Quando gli uccelli insistono nel fabbricare nidi per loro, l’allevatore accurato fornisce protezione (vedere le illustrazioni, pag. 247) e, se gli uccelli lo tollereranno, tenta di tenerli al sicuro dalla molestia. |

||

|

|

|||

|

From the greater ease of controlling fowls, and because the larger kinds of poultry lay comparatively few eggs even when not allowed to incubate those produced during their first laying period, by far the greater number of eggs of all kinds of poultry hatched by natural methods are hatched under hens. |

In base alla maggiore facilità di controllare i polli, e poiché il maggior numero di pollame depone relativamente poche uova anche quando non si permette loro di covare quelle prodotte durante il loro primo periodo di deposizione, di gran lunga il più gran numero di uova di tutti i tipi di pollame covate con metodi naturali vengono covate sotto le galline. |

||

|

|

|||

|

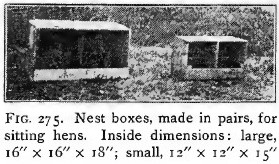

Nests for sitting hens. Nest boxes should be uniform in pattern and size, and should be so constructed that they may be opened and closed at will, thus insuring control of the hens. Where the number to be set is not large, nests of the pattern shown in Fig. 275 may be used. When large numbers are set it is better to have them made in sections of four and arranged in tiers or banks three or four [245] sections high. When nests are placed on the ground the earth bottom should be shaped before putting into the nest material, particular care being taken to remove any small stones that it may contain. |

Nidi per galline che covano . Cassette per nido dovrebbero essere uniformi come modello e grandezza, e dovrebbero essere fatte in modo tale che possono essere aperte e chiuse a volontà, assicurando così il controllo delle galline. Dove non è grande il numero che deve essere messo, possono essere usati nidi del modello mostrato nella fig. 275. Quando ne sono messi grandi numeri è meglio averli fatti in sezioni di 4 e sistemati in file o serie alte 3 o 4 sezioni. Quando i nidi sono messi sul terreno il fondo di terra dovrebbe essere plasmato prima di mettervi il materiale del nido, avendo particolare cura nel rimuovere ogni piccola pietra che può contenere. |

||

|

For nest material. Short, fine hay or straw is preferred for nest material, but fine shavings or excelsior may be used. Some poultry keepers use tobacco stems, which are objectionable to lice. Whatever material is used should be shaped and well pressed down by hand. If this is carelessly done, eggs are likely to be broken, and the hen blamed for what was none of her fault. Those who have had no experience or have been unsuccessful in shaping nests will find it a good plan, after doing their best, to put a few china eggs into the nest and let the hen shape it as she sits on these for a day or two. |

Per il materiale del nido . Il fieno corto, sottile, o la paglia sono preferiti come materiale del nido, ma possono essere usati trucioli sottili o lunghi e sottili. Alcuni allevatori di pollame usano steli di tabacco che sono sgradevoli per i pidocchi. Qualunque materiale venga usato dovrebbe essere plasmato e ben pigiato in giù con la mano. Se ciò è fatto in modo negligente, probabilmente le uova si romperanno, e la gallina sarà accusata per quello che non era affatto colpa sua. Quelli che non hanno avuto alcuna esperienza o che non hanno avuto successo nel foggiare i nidi, troveranno essere un buon programma, dopo aver fatto del loro meglio, mettere alcune uova di porcellana nel nido e lasciare che la gallina gli dia la forma sedendovisi sopra per 1 giorno o 2. |

||

|

|

|||

|

Selection of eggs. Eggs to be incubated should be selected with care, all that are irregular in shape, defective in shell, or abnormal in size being discarded. Leaving out of consideration all other objections to use of such eggs for hatching, their liability to break is sufficient reason for not using them. The eggs should be as fresh as possible, and should be clean. Eggs three weeks old when set may hatch well, but the young birds are likely to be much less vigorous than those from fresh eggs. Little difference is noted between chicks from eggs ten days or two weeks old when set, but it is the general opinion that the fresher eggs produce somewhat better young. Hatches reported from eggs kept six weeks or more are not well authenticated. |

Selezione delle uova . Le uova per essere covate dovrebbero essere selezionate con cura, tutte quelle che sono di forma irregolare, di guscio difettoso, o anormali come volume vanno scartate. Trascurando tutte le altre obiezioni sull’uso di tali uova per essere covate, la loro predisposizione a rompersi è una ragione sufficiente per non usarle. Le uova dovrebbero essere più fresche possibile, e dovrebbero essere pulite. Uova vecchie 3 settimane quando poste nel nido possono schiudere bene, ma è probabile che i giovani uccelli siano molto meno vigorosi di quelli nati da uova fresche. Una piccola differenza è notata tra pulcini da uova vecchie 10 giorni o 2 settimane quando messe a covare, ma è opinione generale che le uova più fresche producono dei giovani alquanto migliori. Schiuse ottenute da uova vecchie 6 settimane o più hanno poco valore. |

||

|

|

|||

|

Eggs kept for hatching should not be exposed to either extreme cold or extreme heat. The best temperature is from 40° to 50° F. It makes no appreciable difference in what position they are placed, nor it is necessary to turn them at intervals; the position does not affect eggs held only a week or two. It is not advisable [246] to put under the same hen the eggs of birds of different kinds or distinctly different types, but it is often advisable to place in the same nest eggs from different flocks, yards, or individual hens, especially if the hatching qualities of some of the matings are known, and it is desired to determine whether, in case of failure of other eggs to hatch, the fault is in the eggs or in incubation. For such purposes eggs must be marked. In general it is desirable that all eggs used for incubation be marked, or that the nests be marked to identify eggs set in them. |

Le uova tenute per essere covate non dovrebbero essere esposte a un freddo o a un caldo estremo. La migliore temperatura è da 40 °F a 50 °F. Non comporta una differenza apprezzabile la posizione in cui sono messe, né è necessario girarle a intervalli; la posizione non influisce sulle uova tenute solo 1 settimana o 2. Non è consigliabile mettere sotto la stessa gallina le uova di uccelli di generi diversi o di tipi chiaramente diversi, ma è spesso consigliabile mettere nello stesso nido uova di gruppi diversi, recinti, o galline individuali, specialmente se le qualità di schiusa di alcuni degli accoppiamenti sono conosciute, e si desidera determinare se, in caso di fallimento di schiusa di altre uova, la colpa è nelle uova o nell’incubazione. Per tali scopi le uova devono essere contrassegnate. In generale è desiderabile che tutte le uova usate per l'incubazione siano contrassegnate, o che i nidi siano contrassegnati per identificare le uova che vi sono poste. |

||

|

Number of eggs placed in a nest. The number of eggs in a setting varies according to the size of the bird, the kind of eggs, and the season. A medium-sized hen can cover from 9 to 15 hens' eggs, ― usually (of average eggs) 11 in winter, 13 in early spring, and 15 after the weather is settled. The same hen would cover 6 or 7 turkey eggs, from 9 to 11 duck eggs, or 4 or 5 goose eggs. A duck will cover about the same number of duck eggs as a hen of like weight. Geese and turkeys cover from 12 to 15 of their own eggs. In warm weather much larger numbers of eggs may be given and large hatches secured,* but because of the risk of the entire hatch being spoiled by a sudden cold snap, big sittings are rarely made except from curiosity. Bantams laying eggs larger for their size than the large fowls will cover only from 7 to 9 of their own eggs, and about the same number of the eggs of pheasants. |

Numero di uova messe in un nido . Il numero di uova in una covata varia a seconda della taglia dell'uccello, del tipo di uova e della stagione. Una gallina di media grandezza può coprire da 9 a 15 uova di galline ― di solito (di uova medie) 11 in inverno, 13 ad inizio primavera e 15 dopo che il tempo è stabile. La stessa gallina coprirebbe 6 o 7 uova di tacchino, da 9 a 11 uova di anatra, oppure 4 o 5 uova di oca. Un'anatra coprirà circa lo stesso numero di uova di anatra come una gallina di pari peso. Oche e tacchini coprono da 12 a 15 delle loro uova. Quando fa caldo possono essere date uova in numero maggiore e sono assicurate abbondanti schiuse,* ma a causa del rischio dell'essere l’intera schiusa rovinata da un improvviso colpo di freddo, le grandi incubazioni vengono fatte raramente eccetto che per curiosità. Le galline nane che per la loro taglia depongono uova più grandi rispetto ai grandi polli, copriranno solo da 7 a 9 delle loro uova, e circa lo stesso numero di uova di fagiani. |

||

|

* I have seen a little native hen weighing less than 4 pounds hatch 19 chicks from 19 eggs. A Brahma hen set on 27 Leghorn eggs hatched 21 chicks. |

* Io ho visto una gallina di razza piccola del peso inferiore a 4 libbre far schiudere 19 pulcini da 19 uova. Una gallina Brahma messa su 27 uova di Leghorn ha fatto schiudere 21 pulcini. |

||

|

Advantages of keeping hens shut on the nests. Except when they are let off to eat and drink, the nests of sitting hens should be kept closed. This is necessary, not so much on account of the individual hen that may leave her nest too long, as to prevent interference and quarreling, with the breakage of eggs and the general disturbance that such incidents occasion. If any are restless they may be kept quiet by darkening the nests with burlap curtains, either over the nest or on the windows. Hens that will not settle down in a darkened room or nest should be discarded. |

Vantaggi di tenere le galline chiuse sui nidi . Eccetto quando sono lasciate fuori per mangiare e bere, i nidi delle galline che covano dovrebbero essere tenuti chiusi. Questo è necessario, non tanto per il fatto che una gallina può lasciare il suo nido troppo a lungo, quanto per prevenire interferenza e litigio, con la rottura di uova e il generale disturbo che tali incidenti provocano. Se alcune sono irrequiete, possono essere tenute tranquille scurendo i nidi con tende di tela da sacchi sul nido o sulle finestre. Galline che non si acquietano in una stanza o in un nido oscurati dovrebbe essere scartata. |

||

|

When only a few hens are set in nests on the ground, and it is desired to manage them with as little interference as possible, they may be let out to feed singly or in pairs, and left to return to the nests of their own accord. When large numbers are set in the same [247] place it is better to let all out at the same time, preferably late in the afternoon, and as soon as they have had feed and drink, return them at random to the nests. The largest average hatches are obtained by not letting hens return regularly to the same nests. One reason for this is that hens differ in temperature, and some are so low in temperature that, if they sit on the same eggs continuously, they will hatch no chicks, or weak chicks. It is possible also that some hens do not move their eggs as much as necessary. It has often been noted that hens that sit closely and are always quiet and in the same position on the nest do not bring off as good hatches as the more energetic and restless hens. |

Quando solo alcune galline sono messe in nidi sul suolo, e si desidera gestirle con il minimo di interferenza possibile, possono essere lasciate uscire per mangiare da sole o in coppie, e lasciate ritornare ai nidi spontaneamente. Quando in grandi numeri sono messe nello stesso luogo è meglio lasciarle uscire tutte nello stesso momento, preferibilmente nel tardo pomeriggio, e appena hanno mangiato e bevuto, farle tornare a casaccio nei nidi. Le più grandi medie di schiuse sono ottenute non lasciando le galline ritornare regolarmente negli stessi nidi. Una ragione di ciò è che le galline differiscono in temperatura, e alcune hanno una temperatura così bassa che, se si siedono continuamente sulle stesse uova, faranno schiudere o nessun pulcino, o pulcini deboli. È anche possibile che alcune galline non muovano le loro uova quel tanto che è necessario. Spesso è stato notato che galline che siedono attentamente e sono sempre quiete e nella stessa posizione sul nido, non portano a termine buone schiuse come le galline più energiche e irrequiete. |

||

|

|

|||

|

While the hens are feeding, nests should be examined for broken or soiled eggs, and attention given to any that are not in order. Some poultrymen, hatching on a large scale, by natural methods, make banks of nests with an alley in the rear and with access to the nests from the back as well as from the front. When the hens are let off to feed, the keeper closes the fronts of all the nests and, going into the alley, can clean the nests, or give other attention, without interfering with the hens or being annoyed by them. |

Mentre le galline stanno nutrendosi, i nidi dovrebbero essere esaminati per eventuali uova rotte o sporche, e per prestare attenzione se qualche uovo non è in ordine. Alcuni avicoltori, facendo covare su larga scala, con metodi naturali controllano i nidi che hanno un vicolo nel retro e un accesso ai nidi dal retro così come dal davanti. Quando le galline sono mandate fuori per mangiare, l’allevatore chiude le facciate di tutti i nidi e, andando nel vicolo, può pulire i nidi, o prestare altra attenzione, senza interferire con le galline o essere importunato da loro. |

||

|

|

|||

|

Whatever arrangement or system of handling sitting hens is used, they should be released to eat and drink at about the same time each day, and at that time nests and eggs soiled by broken eggs or by dung should be cleaned, for there is nothing more detrimental to incubation than fouled eggs and nests. This trouble may be reduced to the [248] minimum by good judgment in the selection of the hens and eggs used, by care in making the nests, and by regularity in attention; but under the best of conditions there will be some breakage, and occasionally a hen unable to retain her feces through twenty-four hours will soil her eggs and nest. |

Qualunque sistemazione o sistema di gestire il covare delle galline venga usato, dovrebbero essere rilasciate per mangiare e bere circa allo stesso momento ogni giorno, e in quel momento i nidi e le uova sporcate da uova rotte o da sterco dovrebbero essere puliti, in quanto nulla è più dannoso per l'incubazione di uova e nidi imbrattati. Questo incomodo può essere ridotto al minimo da un buon giudizio nella selezione delle galline e delle uova usate, dalla cura nel fare i nidi e da regolarità nell’attenzione; ma nelle condizioni migliori ci sarà qualche danno, e di quando in quando una gallina incapace di trattenere le sue feci per 24 ore sporcherà le sue uova e il suo nido. |

||

|

Food of the sitting hen. Only hard grain should be fed to sitting hens. Whole corn seems to suit them best, but any of the ordinary grains may be given. Soft foods and wet mashes, which tend to cause looseness of the bowels, should be avoided, but a little green food may be given as a relish. The grain should be in a hopper, trough, or box, and fresh water should be supplied daily. |

Cibo della gallina che cova . Solo granaglia dura dovrebbe essere data da mangiare a galline che covano. Il mais intero sembra andar meglio per loro, ma qualsiasi granaglia ordinaria può essere data. Cibi molli e pastoni bagnati che tendono a provocare diarrea dovrebbero essere evitati, ma un po’ di cibo verde può essere dato come un piacere. La granaglia dovrebbe essere in una cassetta, in un trogolo o in una scatola, e acqua fresca dovrebbe essere data ogni giorno. |

||

|

Cleanliness. During incubation, and especially if the birds are confined to indoor quarters, as they usually must be early in the season, and as may be most convenient at any time, cleanliness is of the utmost importance. The droppings of the incubating birds are likely to have an unusually offensive odor,* and if allowed to accumulate, to dry, and to be broken up and mixed with the litter or earth of the floor, affect the whole atmosphere of the place, besides making an earth floor so objectionable that hens will not wallow in it and thus keep themselves free from lice. Even when the hens have, and avail themselves freely of, the opportunity to dust, it is advisable to take precautions to prevent lice from getting a start in the nests. The easiest way to do this is to dust hens and nests with insect powder when set (or soon after), again about the middle of the period of incubation, and a third time just before the eggs are picked. If this is done, the birds and nests should be almost entirely free from lice when the chicks hatch. When only a few hens are set, and the keeper is quick to observe indications of the presence of lice and to take steps to check them, routine preventive treatment may be omitted. Under other circumstances preventive measures are safest and, in the end, more economical. |

Pulizia . Durante l'incubazione, e specialmente se gli uccelli sono confinati in alloggiamenti al coperto, come di solito devono esserlo a inizio stagione, e come può essere molto conveniente in qualunque stagione, la pulizia è della massima importanza. È probabile che gli escrementi degli uccelli che covano abbiano un odore insolitamente ripugnante,* e se si concede che si accumulino, per asciugare e per essere spezzati e mescolati con la lettiera o terra del pavimento colpiscono l'intera atmosfera del luogo, oltre a fare una base di terra così deplorevole che le galline non sguazzeranno in essa e così si terrebbero libere dai pidocchi. Anche quando le galline hanno, e si giovano liberamente, l'opportunità di fare un bagno di polvere, per cautelarsi è consigliabile impedire ai pidocchi di cominciare a vivere nei nidi. Il modo più facile per fare ciò è impolverare galline e nidi con polvere per insetto quando messa a punto (o subito dopo), di nuovo a circa metà del periodo d'incubazione, e una terza volta poco prima che le uova vengano forate. Se ciò è fatto, gli uccelli e i nidi dovrebbero essere quasi completamente liberi da pidocchi quando i pulcini nascono. Quando sono sistemate solo poche galline, e l’allevatore è rapido nell’osservare gli indizi della presenza di pidocchi e nel prendere provvedimenti per tenerli sotto controllo, il trattamento preventivo di routine può essere omesso. In altre circostanze misure preventive sono più sicure e, alla fin fine, più economiche. |

||

|

* The extraordinary offensive odor of the droppings of sitting hens seems to be due in part to their long retention before evacuation and in part to the tendency of nature to take advantage of a period of rest from usual activities, to clean up the system and rid it of impurities. |

* L'odore offensivo e straordinario degli escrementi di galline che covano sembra essere dovuto in parte alla loro lunga ritenzione prima dell'evacuazione e in parte alla tendenza della natura ad approfittare di un periodo di pausa dalle solite attività, per pulire il sistema e liberarlo delle impurità. |

||

|

Testing eggs. Eggs should be tested about the seventh day of incubation. When the work is carefully systematized it is usual to set hens always on the same day of the week. Then if the test on [249] the seventh day shows any considerable proportion of infertile, or unhatchable eggs, the good eggs remaining may be "doubled up" and a part of the hens reset with the next lot. A second test is usually made about the fourteenth day for the detection and removal of dead germs. It is much more important that these should be removed than that the infertile eggs should be taken away, for the composition of the infertile egg is not changed during incubation, while the egg containing a dead germ may rapidly decompose, is more likely to be broken than an infertile egg or one with a live germ, and, if broken in the nest, may spoil the hatch. |

Esame delle uova . Le uova dovrebbero essere esaminate intorno al 7° giorno d'incubazione. Quando il lavoro è attentamente sistematizzato è consuetudine il sottoporre le galline sempre nello stesso giorno della settimana. Quindi, se la prova al 7°giorno mostra una considerevole proporzione di uova non fertili, o che non si schiuderanno, le rimanenti uova buone possono essere "raddoppiate" e una parte delle galline ricollocate col prossimo lotto. Una seconda prova è fatta intorno al 14° giorno per la scoperta e la rimozione di germi morti. È molto più importante che questi debbano essere rimossi anziché le uova sterili vengano portate via, in quanto la composizione dell'uovo sterile non è cambiata durante l'incubazione, mentre l'uovo che contiene un germe morto può decomporsi rapidamente, è molto più probabile che venga rotto rispetto a un uovo sterile o a uno con un germe vivo, e, se rotto nel nido, può guastare la schiusa. |

||

|

The method of testing eggs in incubation is substantially the same as the candling of market eggs, but the work is usually done with a little more care. The ordinary incandescent electric light, when convenient, makes a most satisfactory tester. An ordinary hand lamp or lantern may be used, or if the place in which the testing is to be done has a window toward the sun and can be completely darkened, the eggs may be tested by sunlight by placing over this window a shutter, or thick curtain, having in it a hole of suitable size (an inch in diameter, or a little larger), before which the eggs may be passed. When an artificial light is used it may be either placed in a small box with a suitable hole directly before the light, or fitted with a metal chimney with a hole on one side. (See description, p. 171.) The egg to be tested is held, large end up, at the hole before the light. A strongly fertile egg at the seventh day will appear through the tester as in Fig. 294. An infertile egg will be clear, but the yolk may throw a light shadow. The apparent density of the egg will usually be in proportion to the vitality of the germ, and those in which at this time the shadow is relatively faint and the line of the air cell not well defined will not usually hatch. Many poultrymen leave these doubtful eggs until the second test; but it is as well to discard them at the first test, for the germ that does not start well is not likely to produce a strong embryo. |

Il metodo di esaminare le uova in incubazione è sostanzialmente uguale alla speratura di uova per il mercato, ma il lavoro è fatto di solito con un po’ più di attenzione. L’ordinaria luce elettrica incandescente, quando a disposizione, fa un esame più soddisfacente. Possono essere usate una normale lampada a mano o una lanterna, o se il luogo dove l’esame sarà fatto ha una finestra verso il sole e può essere completamente oscurata, le uova possono essere esaminate con la luce del sole mettendo su questa finestra un'imposta, o una tenda spessa, che hanno un buco di dimensione appropriata (1 pollice in diametro, o un po’ più grande) di fronte al quale possono essere passate le uova. Quando è usata una luce artificiale la si può mettere in una piccola scatola con un buco appropriato direttamente di fronte alla luce, o dotata di un camino di metallo con un buco su un lato. (Vedi la descrizione, pag. 171.) L'uovo che deve essere esaminato è tenuto, con la grande estremità in alto, nel buco di fronte alla luce. Un uovo estremamente fertile al 7° giorno apparirà attraverso il saggiatore come nella fig. 294. Un uovo sterile sarà chiaro, ma il tuorlo può proiettare una leggera ombra. La densità apparente dell'uovo sarà di solito in proporzione alla vitalità del germe, e quelle in cui in questo momento l'ombra è relativamente debole e la linea della cella d’aria non è ben definita di solito non schiuderanno. Molti avicoltori lasciano queste uova dubbiose fino al secondo esame; ma è bene scartarle alla prima prova, in quanto il germe che non comincia bene è probabile che non produca un embrione forte. |

||

|

The average hatchable egg, tested with an ordinary light, shows its development only by the increasing density of the shaded portion, the enlargement of the air cell, and the sharper definition of the line between the air cell and the growing embryo. Thin-shelled eggs, or any eggs in very strong light, may show more of the detail [250] of development. As eggs are usually tested with an ordinary lamp, anything noticeable in the shaded portion (as a dark spot, ring, or lines) indicates a dead germ, and vacillation of the lower line of the air space shows that decomposition is well advanced. By slightly turning the egg as held large end up before the light, the condition of the contents may be observed; in the normally developing fertile egg they appear solid, in the decaying egg, fluid. |

L'uovo comune in grado di schiudere, esaminato con una luce ordinaria, mostra il suo sviluppo solo con la densità in aumento della porzione ombreggiata, con l'ingrandimento della cella d’aria, e con la definizione più nitida della linea tra la cella d’aria e l'embrione che sta crescendo. Uova dal guscio sottile, o qualunque uovo di fronte a una luce molto forte, possono mostrare un maggior dettaglio di sviluppo. Siccome le uova sono di solito esaminate con una lampada ordinaria, qualsiasi cosa ben visibile nella porzione ombreggiata (come una macchia scura, un anello, o delle linee) indica un germe morto, e un vacillare della linea più bassa dello spazio d'aria mostra che la decomposizione è assai avanzata. Girando leggermente l'uovo con la grande estremità in alto e tenendolo di fronte alla luce, la condizione dei contenuti può essere osservata; nell'uovo fertile che si sviluppa normalmente essi appaiono solidi, fluidi nell'uovo che si deteriora. |

||

|

Period of incubation. The time required for incubation is for fowls, 21 days ; pheasants, from 22 to 24 days; turkeys, peafowl, and guineas, 28 days; ostriches, 42 days; ducks, 28 days; geese, from 30 to 35 days; swans, 35 days, ― these figures giving the average periods for different types of each kind of poultry and for normal development. It is noticeable that for the smaller kinds of poultry the period of incubation is generally shorter. This is true also of different types of the same kind of poultry. The eggs of small, active birds hatch sooner than those of the larger, more sluggish ones. Broody birds of high temperature will (other things being equal) hatch the same eggs sooner than will those of lower temperature. The young birds hatching long in advance of the normal average time are likely to be precocious individuals. Those much delayed are likely to lack vitality. As a rule, the best specimens are those which hatch promptly after having taken the full period for embryonic development, due allowance being made for differences in the type of the bird and in the birds incubating the eggs. In fowls a hatch of Leghorns might be complete in twenty days; a hatch of Brahmas under the same conditions show not an egg picked at that time. A difference of a day, or even two days, in the apparent period of a hatch may occur, either through failure of the incubating birds to sit closely on the eggs at the outset, or because of partial chilling of the eggs at a later stage of incubation. In the first case the vitality of the young birds may not be at all affected; in the other they are likely to be weak. |

Periodo dell'incubazione . Il tempo richiesto per l'incubazione è di 21 giorni per i polli; da 22 a 24 giorni per i fagiani; 28 giorni per tacchini, pavoni e galline faraone; 42 giorni per gli struzzi; 28 giorni per le anatre; da 30 a 35 giorni per le oche; 35 giorni per i cigni ― questi numeri forniscono i periodi medi per i tipi diversi di ogni genere di pollame e per lo sviluppo normale. È evidente che per i generi più piccoli di pollame il periodo dell'incubazione è generalmente più breve. Questo è vero anche per i tipi diversi dello stesso genere di pollame. Le uova di uccelli piccoli, attivi, schiudono più presto di quelle dei più grandi, dei più pigri. Uccelli di alta temperatura disposti alla cova (le altre cose essendo uguali) fanno schiudere le stesse uova più presto di quelli con temperatura più bassa. I giovani uccelli che fanno schiudere molto in anticipo rispetto al tempo normale è probabile che siano individui precoci. È probabile che quelli molto ritardatari manchino di vitalità. Come regola, i migliori esemplari sono quelli che fanno schiudere prontamente dopo aver usato il pieno periodo per lo sviluppo embrionale, il dovuto abbuono essendo costituito per le differenze nel tipo dell'uccello e negli uccelli che incubano le uova. Nei polli la schiusa di Leghorn sarebbe completa in 20 giorni; una schiusa di Brahma sotto le stesse condizioni non mostra un uovo schiuso in tale intervallo di tempo. Una differenza di 1 giorno, o anche 2 giorni, può verificarsi nel palese periodo di una schiusa, o attraverso il fallimento degli uccelli che covano di sedersi strettamente sulle uova all'inizio, o a causa di un parziale raffreddamento delle uova in uno stadio più tardivo dell'incubazione. Nel primo caso la vitalità dei giovani uccelli non può essere affatto colpita; nell'altro è probabile che siano deboli. |

||

|

Chilling of eggs during incubation. The chilling of eggs cannot be wholly avoided. A bird may become sick, or perhaps die on the nest, before its condition is discovered; and occasionally one, though to all appearances in good health, quits sitting and stands up in the nest. Such a case the novice may at first fail to distinguish from the case of the bird that stands up occasionally (especially in [251] hot weather) because her eggs are making her uncomfortably warm. Unless it is known that eggs have been chilled beyond recovery, the damage due to chilling can be ascertained only by continuing incubation, and testing after a sufficient time has elapsed to plainly show whether development has stopped. In cold weather, eggs left by a bird for only ten or fifteen minutes may be fatally chilled, while in warm weather a bird may remain off for hours at a time without impairing the hatch. An actual chill probably always does damage, but circumstances or superior hardiness sometimes save the germs in some eggs. Cases have been known of vigorous chicks hatching from eggs in nests where most of the germs were destroyed by a chill. |

Raffreddamento delle uova durante l'incubazione . Il raffreddamento delle uova non può essere completamente evitato. Un uccello può diventare ammalato, o forse morire sul nido, prima che la sua condizione sia scoperta; e di quando in quando, sebbene sotto tutti gli aspetti in buona salute, uno smette di covare e sta ritto in piedi sul nido. In tale caso il principiante può innanzitutto non riuscire a distinguere dal caso dell'uccello che sta ritto in piedi di quando in quando (specialmente quando fa caldo) perché le sue uova stanno producendo il suo sgradevole caldo. Salvo che sia noto che le uova sono state raffreddate dopo il recupero, il danno dovuto al raffreddamento può essere accertato solo continuando l'incubazione, ed esaminando dopo che è trascorso un tempo sufficiente per dimostrare chiaramente se lo sviluppo si è bloccato. Quando fa freddo, le uova abbandonate da un uccello per soli 10 o 15 minuti possono essere fatalmente raffreddate, mentre quando fa caldo un uccello può rimanere via per ore e ore senza danneggiare la schiusa. Un freddo effettivo probabilmente danneggia sempre, ma delle circostanze o una robustezza superiore talora salvano i germi in alcune uova. Si è venuti a conoscenza di casi di pulcini vigorosi schiudere da uova in nidi dove la maggior parte dei germi erano stati distrutti dal freddo. |

||

|

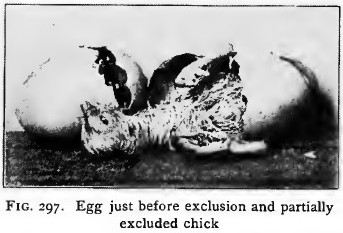

When the eggs begin to hatch. The inclination of the mother is to keep the nest until she is ready to leave it with her young. In houses where the sitters are under control, it is well now to keep the nests closed. The advantage of protecting an outside nest is emphasized at this stage. A nest cover like those shown in Figs. 278 and 279 can be completely closed by a board in front of the entrance, and the sitting bird protected from outside interference at the time when it is most dangerous to her brood. If she is in good condition it will be no serious hardship for her to go without food and water for two or three days, while if she leaves the nest, the air may dry the membranes in pipped eggs and there is risk of her crushing in the shells as she returns. On all accounts she should be allowed to remain quiet. Birds that become too restless and crush their eggs should be removed and others substituted, or (if that cannot be done) the eggs should be taken away. |

Quando le uova cominciano a essere covate . La propensione della madre è di tenere il nido finché è pronta a lasciarlo con il suo piccolo. In case dove le chiocce sono sotto controllo, ora è bene tenere i nidi chiusi. Il vantaggio di proteggere un nido esterno è sottolineato a questo punto. Una coperta di nido come quelle mostrate nelle figure 278 e 279 può essere completamente chiusa da un asse di fronte all'entrata, e l'uccello che sta seduto venir protetto da un’interferenza esterna quando è molto pericolosa alla sua covata. Se è in buone condizioni non sarà per lui una seria fatica procedere senza cibo e acqua per 2 o 3 giorni, mentre se lascia il nido l’aria può asciugare le membrane in uova che pigolano e c'è il rischio che frantumi i gusci quando ritorna. Sotto ogni aspetto gli dovrebbe essere permesso di rimanere tranquillo. Uccelli che diventano troppo irrequieti e schiacciano le loro uova dovrebbero essere rimossi e essere sostituiti da altri, o (se ciò non si può fare) le uova dovrebbero essere portate via. |

||

|

To avoid losses at this stage some poultrymen who hatch mostly with hens transfer the eggs to incubators at about the eighteenth day, returning the chicks to the hens when dry and ready to begin eating. When this is not practicable, and the mother seems likely to lose many of the young as they hatch, the eggs may be put (in the old-fashioned way) into a flannel-lined box or basket and kept in any safe, warm place until they hatch. The nests should be examined only to observe in a general way how things are progressing, and to correct anything going wrong. As a rule, the hen that seems to be doing well should be let alone, the hen that is not doing well relieved of responsibility. When things are going well, all that [252] is necessary is to remove the empty shells, in order to give more room in the nest and to prevent an unhatched egg from being "capped" by a shell. |

Per evitare perdite in questo stadio alcuni avicoltori che usano soprattutto le galline per covare trasferiscono le uova nelle incubatrici intorno al 18° giorno, ridando i pulcini alle galline quando asciutti e pronti a cominciare a mangiare. Quando questo non è fattibile, e la madre sembra probabilmente perdere molti dei giovani quando schiudono, le uova possono essere messe (nel vecchio modo) in una scatola foderata di flanella o in un cesto e tenuti in qualunque luogo sicuro e caldo fino a quando schiudono. I nidi dovrebbero essere esaminati solo per osservare in modo generale come le cose stanno progredendo, e correggere qualsiasi cosa sbagliata. Come regola, la gallina che sembra stia agendo bene dovrebbe essere lasciata da sola, la gallina che non sta agendo bene dovrebbe venir sollevata da ogni responsabilità. Quando le cose stanno andando bene, tutto ciò che è necessario è rimuovere i gusci vuoti per dare più spazio nel nido e impedire a un uovo non schiuso dell'essere "incappucciato" da un guscio. |

||

|

|

|||

|

Helping birds out of the shell. On the principle that the bird that has not strength to get out of the shell unassisted is not worth keeping, most experienced poultrymen consider it inadvisable to help them out. Few, however, rigidly follow this rule. Especially in hatching by natural methods, where the eggs are easy to get at, the attendant is likely to help out of the shell every chick that seems to need help, and discard the weaklings later, when removing the chicks from the nests. This saves the chick that is held in the shell by something else than lack of strength to make its way out under normal conditions. Such cases occur when the membranes dry as the chick picks around the shell, and when the chick is "mispresented" and picks at the small instead of the large end of the egg. If the drying of membranes as eggs are picked is general, it is a good plan to moisten the nest with tepid water, and also, if conditions are very bad, to sprinkle the floor of the apartment liberally. Except in such circumstances, it is not necessary to moisten eggs in process of incubation by the natural method. In removing the shell from a chick which seems to need help, the condition of the blood vessels in the membrane should be noted. While the blood still circulates in them, nothing should be done. The chick will be injured or killed by the bleeding that would follow the removal of shell and membrane. |

Aiutando gli uccelli fuori dal guscio . In base al principio che l'uccello che non ha la forza per uscire dal guscio senza aiuto non vale la pena tenerlo, molti avicoltori esperti considerano sconsigliabile aiutarlo a uscire. Comunque, pochi seguono rigidamente questa regola. Specialmente nel covare con metodi naturali, per cui le uova sono facili da afferrare, è probabile che l’addetto aiuti a uscire fuori del guscio ogni pulcino che sembra necessitare di aiuto, e scarta più tardi i malaticci quando rimuove i pulcini dai nidi. Questo salva il pulcino trattenuto nel guscio da qualcosaltro rispetto alla mancanza di forza per fare la sua via d’uscita in condizioni normali. Accadono tali casi quando le membrane si asciugano in quanto il pulcino spezza il guscio circolarmente, e quando il pulcino è "malpresentato" e spezza la piccola invece della grande estremità dell'uovo. Se è comune l’essiccare membrane quando le uova sono forate, è un buon programma inumidire il nido con acqua tiepida, e anche, se le condizioni sono molto cattive, spruzzare abbondantemente il pavimento dell'appartamento. Eccetto che in tali circostanze, non è necessario inumidire le uova in corso d'incubazione in modo naturale. Nel rimuovere il guscio da un pulcino che sembra necessitare di aiuto, la condizione dei vasi sanguigni nella membrana dovrebbe essere notata. Mentre il sangue vi circola ancora, nulla si dovrebbe fare. Il pulcino sarà danneggiato o ucciso dall'emorragia secondaria alla rimozione del guscio e della membrana. |

||

|

Conditions of good hatching. Success in hatching by natural methods depends on constant and careful attention to every detail [253] that may affect results. While the natural method is the only one available for those who cannot give an incubator as close attention as its heater requires, the poultry keeper who leaves sitting birds to themselves is taking chances. Under favorable conditions a single bird sitting by itself may make a good hatch. A few birds may do as well if they get along amicably, but good or even fair hatches are exceptional under such circumstances. As a rule, good results by natural methods are secured only by careful selection of eggs and sitters, careful preparation of nests, regular attention to the wants of the birds, and prompt correction of any condition unfavorably affecting either the germs in the eggs or the mothers at hatching time. The natural method of incubation, at its season and in its place, is the more economical method, and taxes the thought of the operator less than the other, but to get full results from it the operator must do his part as faithfully as he expects his birds to do theirs. |

Le condizioni di un buon covare . Il successo nel covare con metodi naturali dipende da una costante e accurata attenzione per ogni dettaglio che può influire sui risultati. Mentre il metodo naturale è il solo disponibile per quelli che non possono dare a un'incubatrice un’attenzione tanto stretta come il suo riscaldatore richiede, l’allevatore di pollame che lascia gli uccelli che covano a sé stessi sta correndo dei rischi. In condizioni favorevoli un singolo uccello che cova da solo può determinare una buona schiusa. Pochi uccelli possono agire bene cavandosela amichevolmente, ma buone o anche belle schiuse sono eccezionali in tali circostanze. Come regola, buoni risultati da metodi naturali sono assicurati solo da una selezione accurata di uova e galline che covano, da una preparazione accurata dei nidi, da un’attenzione regolare alle necessità degli uccelli, e da una pronta correzione di qualunque condizione che colpisce sfavorevolmente o i germi nelle uova o le madri al momento della schiusa. Il metodo naturale dell'incubazione, alla sua stagione e nel suo luogo, è il metodo più economico, e grava sul pensiero dell'operatore meno dell'altro, ma per ottenerne i pieni risultati l'operatore deve fare la sua parte esattamente come lui si aspetta che i suoi uccelli facciano le loro. |

||

|

Hatching by Artificial Methods |

Covando con metodi artificiali |

||

|

Responsibility of the operator. The modern incubator is a cleverly designed, serviceable mechanism, but it has its limitations. Many of the troubles of incubator operators are due to overestimates of the automatic capacity of incubators, and to the consequent neglect of things to which the operator should give his personal attention. The most successful operators are those who watch their incubators very closely, quite ignoring the manufacturer's claim that the machine will do its work with a little attention every twelve hours, and that no serious harm will result if the operator happens to leave it alone for twenty-four hours. The facts as to this are, as the experienced operator has learned, that while an incubator may run for weeks without requiring attention except at the regular intervals, it may go wrong at any time, and many hatches are lost which might have been saved had the operator been on the lookout to promptly correct wrong conditions. When operations are on a large scale the risk of loss is so great that the wise poultry keeper takes no unnecessary chances, but looks after his incubators and brooders early, often, and late. In small operations it may not seem profitable to give the time to this, and on the actual value of the eggs, or of the chicks when hatched, it may not be profitable; [254] but considering such points in their general relation to his work, the poultry keeper will find that he cannot afford to leave undone anything that it is in his power to do in order to hatch, at the most favorable season, the young stock that he needs. Special emphasis has been laid upon this point, because economy of attention which amounts to neglect of incubators is the great stumblingblock of the small operator. |

Responsabilità dell'operatore . La moderna incubatrice è un meccanismo progettato con intelligenza, utile, ma ha le sue limitazioni. Molti dei guai di operatori di incubatrice sono dovuti a stime in eccesso della capacità automatica delle incubatrici, e alla conseguente negligenza di cose alle quali l'operatore dovrebbe dare la sua personale attenzione. Gli operatori più validi sono quelli che guardano molto da vicino le loro incubatrici, ignorando completamente la richiesta del fabbricante che la macchina farà il suo lavoro con una piccola attenzione ogni 12 ore, e che nessun danno serio risulterà se all'operatore accade di lasciarla per 24 ore da sola. Come l'operatore esperto ha imparato i fatti relativi sono che mentre un'incubatrice può funzionare per settimane senza richiedere attenzione eccetto che a intervalli regolari, può andar male in qualunque momento, e si perdono molte schiuse che avrebbero potuto essere salvate se l'operatore fosse stato in guardia per correggere prontamente condizioni sbagliate. Quando le operazioni sono su larga scala, il rischio di perdita è così grande che il saggio allevatore di pollame non assume rischi non necessari, ma controlla le sue incubatrici e covatrici di buon'ora, spesso e tardi. Nelle piccole operazioni non può sembrare utile dedicare il tempo a questo, e può non essere proficuo sul valore attuale delle uova, o dei pulcini quando schiusi; ma considerando tali punti nella loro relazione generale al suo lavoro, l’allevatore di pollame troverà che lui non può permettersi di lasciare incompiuta qualsiasi cosa che è in suo potere fare per far schiudere, nella stagione più favorevole, il giovane gruppo di cui ha bisogno. Enfasi speciale è stata fatta su questo punto, perché l’economia di attenzione che equivale a trascurare le incubatrici è di grande ostacolo per il piccolo operatore. |

||

|

|

|||

|

Selection of an incubator. The choice of an incubator is a less important matter than is commonly supposed. Although there are manufactured in America over a hundred differently named incubators, most of them are imitations of popular machines, the imitation being sometimes inferior in construction or different in some particular, but as often equal to, and occasionally an improvement on, the model. It is notorious that some of the best-known incubators on the market are substantially identical and as nearly equal as may be in hatching results, the differences in hatches of machines of different makes being no more noticeable than differences in hatches from machines of the same make. It is not unusual to find poultrymen in the same locality preferring different machines. Even men operating in the same room, with the same eggs, may not agree in their [255] choice of an incubator. Some operators can get good results from any machine, others cannot successfully run at the same time machines requiring different adjustments. |