Principles

and practice of poultry culture – 1912

John Henry Robinson (1863-1935)

Principi

e pratica di pollicoltura – 1912

di John Henry Robinson (1863-1935)

Trascrizione e traduzione di Elio Corti![]()

2016

Traduzione assai difficile - spesso incomprensibile

{} cancellazione – <>

aggiunta oppure correzione

CAPITOLO XXVI

|

[475] CHAPTER XXVI |

CAPITOLO XXVI |

|||

|

APPLICATION OF THE PRINCIPLES |

APPLICAZIONE DEI PRINCIPI |

|||

|

The work of the breeder consists in intelligent direction of the natural laws of reproduction for certain definite purposes. His object is not (as is so often erroneously supposed) to secure the perpetuation of natural types, or of the types of domestic live stock which would develop under any given conditions if he did not interfere. If such were his objects, all that would be necessary would be to destroy individuals presenting marked variations from the common type and to allow others to mate according to chance and inclination. The breeder’s part in the development of domestic races is to bring order out of the chaos of variation called mongrelism. From a practically unlimited stock of types he selects the few found most serviceable, or which seem to him most beautiful, fixes these types and tries to persuade others to use and preserve them. What nature would do in any particular case interests him either not at all or only as it gives him an insight into the properties of the living matter with which he works. While the standards to which he breeds are practically fixed, in successful individual work in breeding the results are always progressive. If the first independent efforts of a breeder show improvement in good stock, that is usually due to chance and is likely to be lost in the next trial. It is when the poultry breeder finds, year after year, better quality in his good birds and a larger proportion of birds of high quality, that he knows that he is applying principles correctly. |

Il lavoro dell’allevatore consiste in una intelligente gestione delle leggi naturali di riproduzione per certi definiti scopi. Il suo oggetto non è (come è tanto spesso erroneamente supposto) assicurare la perpetuazione dei tipi naturali, o dei tipi del gruppo domestico vivente che si svilupperebbero sotto alcune determinate condizioni se lui non interferisse. Se tali fossero i suoi scopi, tutto ciò che sarebbe necessario sarebbe distruggere individui che presentano marcate variazioni dal tipo comune e permettere agli altri di accoppiarsi secondo l’opportunità e la propensione. La parte dell’allevatore nello sviluppo delle razze domestiche è portare ordine del caos di variazione chiamata ibridismo. Da un gruppo praticamente illimitato di tipi lui seleziona i pochi trovati molto utili, o che a lui sembrano più belli, fissa questi tipi e tenta di persuadere altri ad usarli e conservarli. Tale natura farebbe in ogni caso particolare che lo interessa oppure per niente affatto o solo in quanto gli dà un intuito nelle proprietà della materia vivente con cui lavora. Mentre gli standard per i quali lui alleva sono praticamente fissati, in un lavoro individuale riuscito allevando i risultati sono sempre progressivi. Se i primi sforzi indipendenti di un allevatore mostrano un miglioramento in un buon gruppo, ciò è abitualmente dovuto alla buona sorte e probabilmente va persa nella prossima prova. È quando l’allevatore di pollame trova, anno dopo anno, la migliore qualità nei suoi buoni uccelli e una più grande quantità di uccelli di alta qualità che lui riconosce che sta applicando correttamente i principi. |

|||

|

While it is not to be expected that the independent work of a novice in breeding stock of any type will give at first a high grade of results, there is no need of the rapid regression from type, and deterioration of quality, usually shown in the work of the novice beginning with good poultry. With very rare exceptions novices in poultry breeding begin their work with two wrong ideas firmly fixed in their minds. They suppose that absolute purity of blood [476] gives uniformity in results, and that the great evil they have to guard against in breeding is loss of vitality and of "practical qualities" through breeding from birds near akin. |

Mentre non ci si deve aspettare che il lavoro indipendente di un novizio nell’allevare un gruppo di qualche tipo darà subito un alto grado di risultati, non c’è alcun bisogno della regressione rapida dal tipo, e il deterioramento di qualità, di solito mostrato nel lavoro del novizio che comincia con del buon pollame. Con molto rare eccezioni i novizi nell’allevare il pollame cominciano il loro lavoro con due idee sbagliate fermamente fissate nelle loro menti. Essi suppongono che una purezza assoluta del sangue dà un’uniformità nei risultati, e che il grande danno che loro devono evitare nell’allevare è la perdita della vitalità e di "qualità pratiche" attraverso un allevamento da uccelli vicini alla consanguineità. |

|||

|

The history of the development of races shows very plainly that the development and preservation of artificial types depends upon systematic, continuous selection. The fact that self-division is the first form of reproduction, and that self-fertilization is the law in both the vegetable and the animal kingdom until a high stage of development through variation is reached and sex becomes necessary as a check on variation, shows that inbreeding is not in itself detrimental. The breeder who accepts these two facts at the beginning of his work is in a position with reference to it which no one who fails to apprehend them ever reaches. It would be hard to find a successful poultry breeder who did not date the beginning of his success from the time when he came to appreciate the fact that any breed or variety in his hands became what he made it, and that outbreeding tended always to disintegration of well-established types. The effective use of principles of breeding as deduced from phenomena of reproduction depends on the application of principles without prejudice. |

La storia dello sviluppo delle razze mostra molto chiaramente che lo sviluppo e la conservazione di tipi artificiali dipendono da una selezione sistematica, continua. Il fatto che l’auto divisione è la prima forma di riproduzione, e che l’autofecondazione è la legge nel regno sia vegetale che animale fino a che un alto stadio di sviluppo attraverso la variazione è raggiunto e il sesso diviene necessario come un controllo sulla variazione, dimostra che l’accoppiamento tra soggetti consanguinei non è in se stesso dannoso. L’allevatore che accetta questi due fatti all’inizio del suo lavoro è in una posizione con riferimento al fatto che nessuno che fallisce per apprenderli sempre li raggiunge. Sarebbe duro trovare un valido allevatore di pollame che non ha attribuito l’inizio del suo successo da quando giunse ad apprezzare il fatto che ogni razza o varietà nelle sue mani divenne quello che lui fece, e che l’esogamia tese sempre alla disintegrazione di tipi ben stabiliti. L’uso effettivo di principi di allevamento come dedotto da fenomeni di riproduzione dipende dall’applicazione di principi senza pregiudizio. |

|||

|

Adaptability of poultry breeding. In poultry breeding, and particularly in the breeding of fowls, we find the one line of animal breeding open to every one who has the use of a little land. The ordinary farmer cannot be an independent breeder of horses or cattle; the number of animals he can produce and mature on his farm is not large enough to give him either the necessary experience or a proper selection of breeding stock. With sheep and hogs the ordinary farmer may, if he is so inclined, do something in the way of special breeding. With poultry the resident on a village lot may do in a few years more actual work in breeding than most growers of other domestic live stock can do in a lifetime. The relatively small individual value of ordinarily good breeders, and the rapid rate of increase in poultry, make it possible for a breeder to secure a few good individuals by a very small investment, and to build up a large stock in a short time. |

L’adattabilità dell’allevamento del pollame . Nell’allevamento del pollame, e particolarmente nell’allevamento dei polli, noi troviamo una linea di condotta di allevamento animale aperta a chi ha l’uso di un piccolo terreno. Il fattore ordinario non può essere un libero allevatore di cavalli o bovini; il numero di animali che può produrre e può portare a maturità nella sua fattoria non è grande abbastanza o per dargli l’esperienza necessaria o una selezione corretta del gruppo in allevamento. Con pecore e porci l’allevatore ordinario può, se è propenso, fare qualcosa nell’allevamento speciale. Con pollame il residente in un appezzamento di villaggio può fare in pochi anni più lavoro effettivo nell’allevare di quanto la maggior parte degli allevatori di altri gruppi domestici vivi possono fare in una vita. Il relativamente piccolo valore individuale di allevatori ordinariamente buoni, e la rapida percentuale di aumento nel pollame, rende possibile per un allevatore assicurare alcuni buoni individui attraverso un investimento molto piccolo, e sviluppare un grande gruppo in un tempo breve. |

|||

|

Length of life and breeding value. The short life of most kinds of poultry is a disadvantage to the breeder, in that the full measure of the breeding value of an individual may not be found [477] until its usefulness as a breeder is nearly over. The value of a stallion or a mare, or of a bull or a cow, as a breeder may be demonstrated long before the animal has reached its prime. Then many years of life remain in which the breeder may use a few selected individuals year after year. But except in the larger and less productive kinds of poultry, the breeder must make a large proportion of new matings every year. The numbers produced by even large stock breeders are less than those produced by the average small poultry breeder. The poultry breeder usually has an abundance of material, for selection, and if he attends to it year by year, may make much more rapid progress in any desired direction than the breeder of cattle and horses. On the other hand, inattention to selection of breeders for a year is almost certain to put him back two or three years, while two or three years’ relaxation of vigilance in efforts to maintain or develop a type will usually make it necessary for him to begin all over again. A breeder of horses or cattle might neglect special attention to breeding for several years, and yet, if he retained a part of his stock, take the work up again about where he left it, and with the same individuals. In a like period of time a neglected stock of fowls or ducks would include a very small proportion of individuals of known breeding. The breeder of poultry has to give practically constant attention to the selection of breeders. |

Lunghezza della vita e valore dell’allevare . La vita breve di molti tipi di pollame è uno svantaggio per l’allevatore, in quanto la piena misura del valore di allevamento di un individuo non può essere trovata fino a che la sua utilità come riproduttore è quasi finita. Il valore di uno stallone o di una cavalla, o di un toro o di una vacca come riproduttore può essere dimostrato da molto prima che l’animale abbia raggiunto il suo pieno sviluppo. Quindi rimangono molti anni della vita in cui l’allevatore può usare pochi individui selezionati anno dopo anno. Ma eccetto che nei tipi più grandi e meno produttivi di pollame, l’allevatore deve fare una grande percentuale di nuovi accoppiamenti ogni anno. I numeri prodotti anche da allevatori di grandi gruppi sono inferiori a quelli prodotti dall’allevatore di un pollame mediamente piccolo. L’allevatore di pollame ha di norma un’abbondanza di materiale per la selezione, e se lui lo assiste di anno in anno, può fare un progresso molto più rapido in ogni desiderata direzione rispetto all’allevatore di bestiame bovino e di cavalli. D’altra parte la disattenzione per la selezione di allevatori per un anno è quasi sicura per metterli indietro di 2 o 3 anni, mentre 2 o 3 anni il attenuazione di vigilanza in sforzi per mantenere o sviluppare un tipo renderà per lui necessario ricominciare di nuovo tutto. È probabile che un allevatore di cavalli o di bestiame bovino trascuri una speciale attenzione ad allevare per molti anni, e ancora, se ha trattenuto una parte del suo gruppo, riprende di nuovo il lavoro circa dove lo lasciò, e con gli stessi individui. In un tale periodo di tempo un gruppo trascurato di polli o anatre includerebbe una proporzione molto piccola di individui di allevamento noto. L’allevatore di pollame deve prestare un’attenzione praticamente continua alla selezione degli animali da riproduzione. |

|||

|

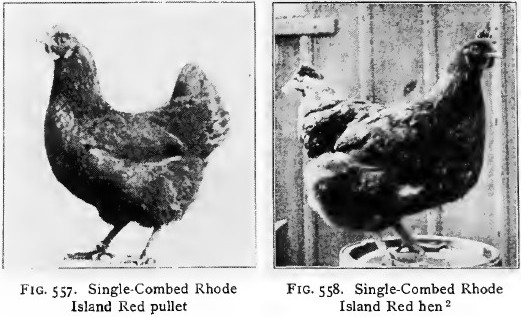

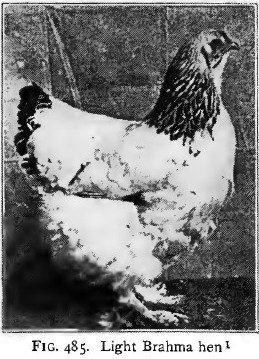

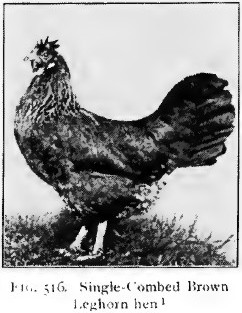

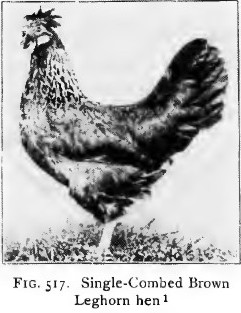

Relative value of male and female. If in polygamous creatures the females produce normally but one or two young at a birth and breed but once a year, the apparent breeding value of a male, bred to any given number of females, is equal to that of all the females, for he has a one-half influence on the progeny of all, while the hereditary influence of each female is limited to her own progeny. Then whatever of peculiar merit an individual in any generation may take from its dam is limited to that individual. Its sire and dam may reproduce its like, one or a few each year. When it arrives at maturity, it may reproduce its special merit in its offspring, ― if a male it may reproduce its type in a considerable number; if a female, in a very limited number each year. Under such conditions a male of great individual merit or prepotency is much more valuable than a female. As the number of young produced by the female increases, her practical value in reproduction [478] of type as compared with that of the male increases; for while the male may still influence a very much larger number of offspring, the female may produce enough offspring in a season to enable a breeder to produce in the next season hundreds or even thousands of young from matings of her offspring. As between a male and female of equal breeding value, polygamous mating constitutes a handicap of one generation on the female. This, where a generation matures in less than a year, is a very slight difference. An experienced and skillful poultry breeder places as high a value on the female in his breeding operations as on the male, though commercially the male is more valuable because a purchaser may realize more quickly on his investment. |

Valore relativo di maschio e femmina . Se in creature poligame le femmine normalmente producono 1 o 2 giovani a una nascita e si accoppiano solo una volta l’anno, l’apparente valore di procreazione di un maschio, accoppiato con qualunque numero determinato di femmine, è uguale a quello di tutte le femmine, in quanto lui ha una mezza influenza sulla progenie di tutte, mentre l’influenza ereditaria di ogni femmina è limitata alla loro propria progenie. Per cui qualunque cosa di merito particolare un individuo in ogni generazione può assumere dalla sua genitrice è limitata a quell’individuo. Il suo progenitore e la genitrice possono riprodurre come il suo, uno o un poco ogni anno. Quando arriva alla maturità, può riprodurre il suo merito speciale nella sua prole ― se un maschio può riprodurre il suo tipo in un numero considerevole; se una femmina, in un numero molto limitato ogni anno. Sotto tali condizioni un maschio di grande valore individuale o la prepotenza è molto più preziosa di una femmina. Siccome il numero di giovani prodotti dalla femmina aumenta, il suo valore pratico aumenta nella riproduzione del tipo come paragonato con quello del maschio; siccome mentre il maschio può ancora influenzare un numero molto più grande di prole, la femmina può produrre abbastanza prole in una stagione per mettere in grado un allevatore a produrre nella prossima stagione centinaia o anche migliaia di giovani da accoppiamenti della sua prole. Come tra un maschio e una femmina di uguale valore procreativo l’accoppiamento poligamo costituisce un intralcio di una generazione sulla femmina. Questo, dove una generazione matura in meno di un anno, è una differenza molto esigua. Un allevatore di pollame esperto e abile pone nelle sue operazioni di allevamento un alto valore sulla femmina come sul maschio, sebbene commercialmente il maschio è più prezioso perché un acquirente può realizzare più rapidamente sul suo investimento. |

|||

|

Selection. In nature the established type of a species or a variety is the type that is best adapted to its environment. Such types develop as a result of natural selection, defined by Darwin as "the survival of the fittest." In improved domestic races types are arbitrarily determined by man in accordance with his needs or his tastes, and are secured and maintained by allowing only individuals of the desired types to propagate their kind. Such types are called artificial types (breeds) and the system of selection by which they are made and preserved is called artificial selection. |

Selezione . In natura il tipo stabilito di una specie o una varietà è il tipo che è meglio adattato al suo ambiente. Tali tipi si sviluppano come un risultato di selezione naturale, definito da Darwin come "la sopravvivenza del più appropriato." Nelle razze domestiche migliorate i tipi sono arbitrariamente determinati dall’uomo in concordanza con le sue necessità o i suoi gusti, e sono assicurati e mantenuti permettendo solo agli individui dei tipi desiderati di propagare il loro tipo. Tali tipi dono detti tipi artificiali (razze) e il sistema di selezione col quale sono fatti e conservati è detto selezione artificiale. |

|||

|

Superficially, artificial and natural selection often seem to proceed on radically different principles, and so are by many regarded as essentially antagonistic. The impression is very general that artificial selection is unnatural, ― at variance with nature. This is true only when by artificial selection the development or suppression of a character is carried to the point where the result becomes detrimental to the race. In domestication natural selection becomes in a measure inoperative, and the natural type varies and multiplies indefinitely. Artificial, or intelligent, selection then becomes necessary for the isolation and development of a limited number of the types arising. In the wild state conditions make it impossible for many special types of a species to develop in the same territory. In domestication, man may develop, by the control and separation of individuals, as many types as he wishes. As long as selection does not unduly disturb the natural equilibrium of characters, artificial selection is not unnatural; and in so far as, without injury to others, it develops special characters beyond what [479] is possible under natural conditions, it is better than natural selection. The difference between the common type of a wild race and the finest type of the same race in domestication is a measure of the difference, in its value to man, of natural and artificial selection. |

La selezione artificiale e naturale spesso sembrano procedere superficialmente su principi radicalmente diversi, e così da molti sono considerate come essenzialmente antagonistiche. È molto generale l’impressione che la selezione artificiale è innaturale ― in disaccordo con la natura. Questo è vero solo quando con la selezione artificiale lo sviluppo o soppressione di un carattere è portato al punto in cui il risultato diventa dannoso alla razza. In stato di addomesticazione la selezione naturale diviene in un certo grado non operante, e il tipo naturale varia e si moltiplica indefinitamente. Artificiale, o intelligente, la selezione diviene allora necessaria per l’isolamento e lo sviluppo di un numero limitato dei tipi che compaiono. Nello stato selvatico le condizioni rendono impossibile per molti tipi speciali di una specie svilupparsi nello stesso territorio. In stato di addomesticazione, l’uomo può sviluppare, con il controllo e la separazione degli individui, tanti tipi quanti desidera. Finché la selezione non disturba in modo inopportuno il naturale equilibrio dei caratteri, la selezione artificiale non è innaturale; e nella misura in cui, senza danno ad altri, sviluppa caratteri speciali oltre quello che è possibile sotto naturali condizioni, è meglio della selezione naturale. La differenza tra il tipo comune di una razza selvatica e il tipo migliore della stessa razza in addomesticazione è una misura della differenza, nel suo valore per l’uomo, tra una selezione naturale e artificiale. |

|||

|

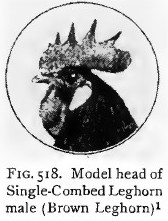

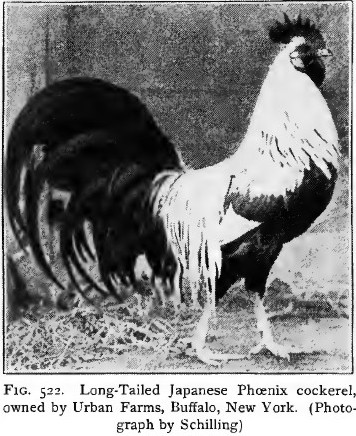

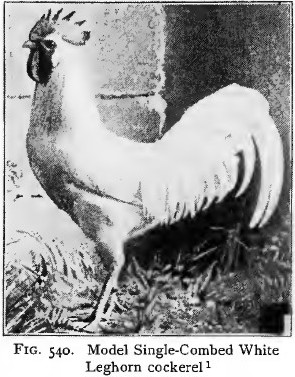

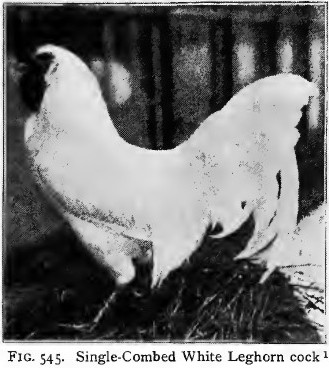

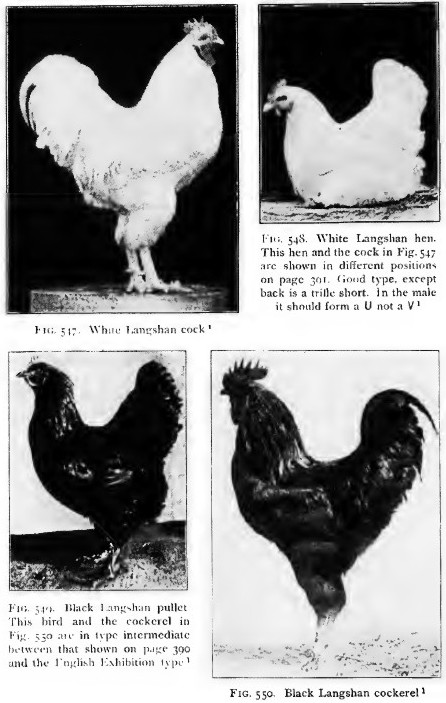

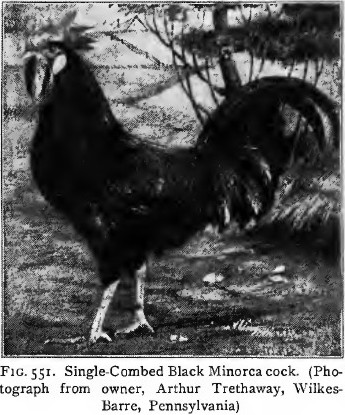

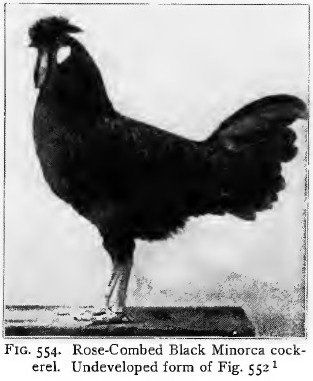

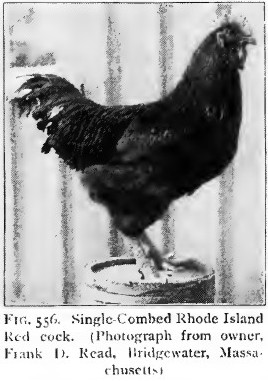

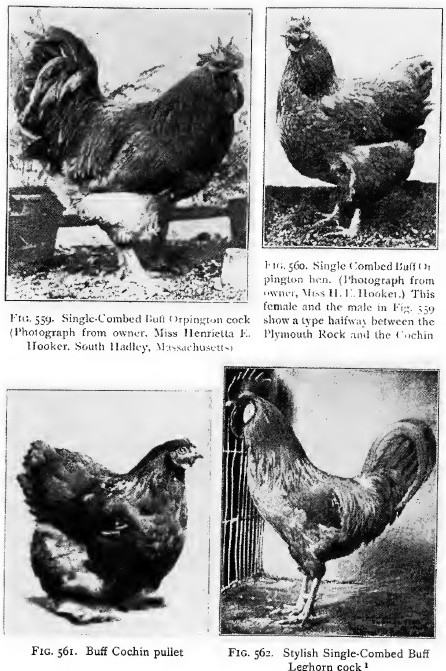

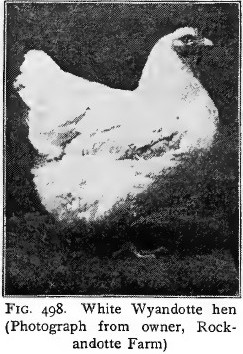

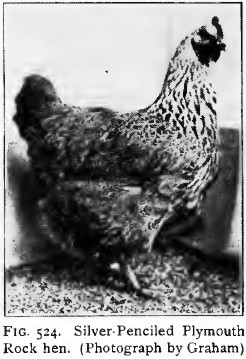

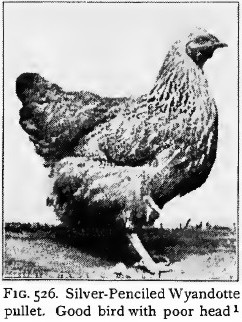

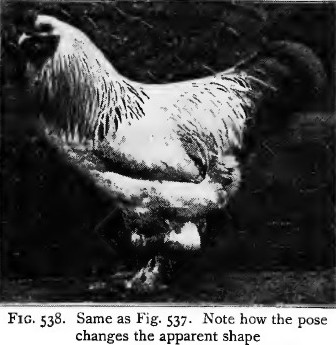

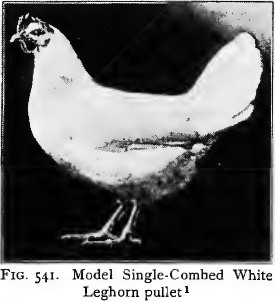

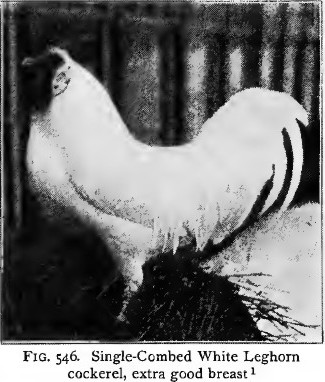

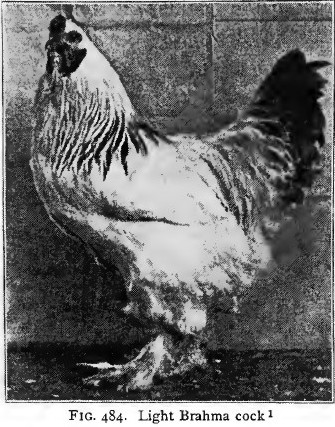

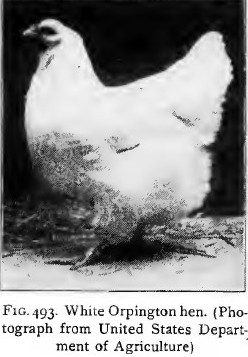

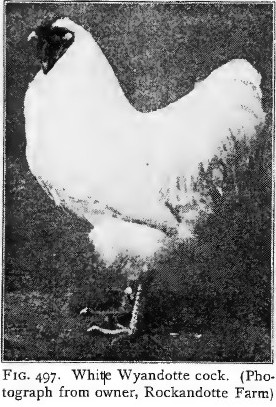

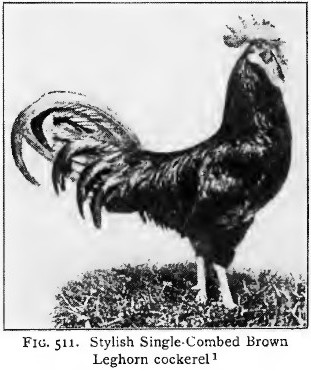

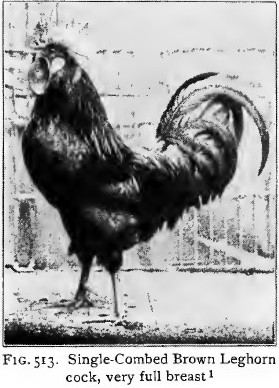

Poultry standards. The continuance and distribution of a specific type or variety in domestication depend upon the agreement of breeders on a standard for that type. In the development of a breed or variety in any locality an unwritten standard is gradually evolved, and the breeders are loosely governed by that standard. When a variety is widely distributed and competitive exhibitions bring together stock from many localities, a written standard becomes necessary. Unwritten standards, as a rule, relate only to the most conspicuous features of a type, and allow great variation in details. Written standards undertake to establish size and weight and to describe every visible character. They are usually mere outlines, and often seem vague to those not familiar with the varieties described and with the popular types. Even when descriptions are supplemented by pictorial illustrations, a written standard is quite inadequate as a description of a variety. In studying a standard the novice must use as illustrations live birds of known values as commonly measured by that standard. The standard of a breed or variety describes the assumed perfect type of every character of that variety. Such a standard is ideal, in that the model form of each and every character is not often found in any one bird.* |

Gli standard del pollame . La durata e la distribuzione di un tipo specifico o di una varietà in addomesticazione dipendono dall’accordo degli allevatori su uno standard per quel tipo. Nello sviluppo di una razza o varietà in qualunque località uno standard non scritto è gradualmente evoluto, e gli allevatori sono liberamente governati da tale standard. Quando una varietà è estesamente distribuita e le esposizioni competitive portano insieme un gruppo da molte località, uno standard scritto diventa necessario. Standard non scritti, come regola, riferiscono solamente sulle caratteristiche più evidenti di un tipo, e permettono una grande variazione nei dettagli. Standard scritti si incaricano di stabilire taglia e peso e di descrivere ogni carattere visibile. Sono di solito meri abbozzi, e spesso sembrano imprecisi per quelli che non sono familiari con le varietà descritte e coi tipi popolari. Anche quando le descrizioni sono integrate da illustrazioni pittoriche, uno standard scritto è piuttosto inadeguato come descrizione di una varietà. Nello studiare uno standard il novizio deve usare come illustrazioni uccelli vivi di valori noti come comunemente misurati da quello standard. Lo standard di una razza o varietà descrive il presunto tipo perfetto di ogni carattere di quella varietà. Tale standard è ideale, in quanto la forma di modello di ognuno e ogni carattere spesso non è trovato in alcun uccello.* |

|||

|

* The technical fiction is that the perfect bird cannot be produced. While the proportion to the whole number is small, many birds are produced which only hypercritical judgment can find fault with. |

* La finzione tecnica è che l’uccello perfetto non può essere prodotto. Mentre la proporzione con il numero intero è piccola, si producono molti uccelli che solamente un giudizio ipercritico può trovarvi un difetto. |

|||

|

The ordinary view of standards makes such a standard (in theory) the ideal toward which all breeders are striving. Actually, considering the relations of a standard to its variety at different periods of the history of the variety, and the inevitable differences in interpretation of its provisions, a written standard only indicates general directions and bounds, and the exact type in style at any time can be learned only by observation of the type that wins most prizes at leading shows. |

La visione ordinaria degli standard rende tale standard (in teoria) l’ideale verso il quale stanno sforzandosi tutti gli allevatori. Effettivamente, in considerazione delle relazioni di uno standard con la sua varietà in periodi diversi della storia della varietà, e le differenze inevitabili nell’interpretazione delle sue norme, solo uno standard scritto indica direttive generali e limiti, e il tipo esatto in stile in ogni tempo può essere appreso solo con l’osservazione del tipo che vince più premi alle mostre principali. |

|||

|

The term "’standard" is technically (but not discriminatingly) used in this country with specific reference to varieties described in [480] the "American Standard of Perfection"* published by the American Poultry Association. |

Il termine "’standard" è tecnicamente (ma non in modo discriminate) usato in questo paese con lo specifico riferimento a varietà descritte in "American Standard of Perfection"* pubblicato dall’American Poultry Association. |

|||

|

* In a general way the practice of the American Poultry Association has been to give recognition to breeds or varieties at an advanced stage of development whenever a considerable number of persons showed interest in the matter, but it has frequently happened that breeds that were quite popular were refused recognition, while others in which few were interested have been admitted. Recognition in the Standard of Perfection usually implies that considerable progress has been made in fixing the type. The fact that a breed or variety is not in the Standard tells nothing as to its quality. |

* In modo generale la pratica dell’American Poultry Association è stata quella di dare un riconoscimento a razze o varietà ad avanzato stadio di sviluppo ogni qualvolta un numero considerevole di persone mostrava interesse in materia, ma è frequentemente accaduto che quelle razze che erano piuttosto popolari erano rifiutate dall’essere riconosciute, mentre altre nelle quali si aveva poco interesse sono state ammesse. Il riconoscimento nello Standard of Perfection di solito implica che è stato fatto un considerevole progresso nel fissare il tipo. Il fatto che una razza o varietà non è nello Standard nulla dice circa la sua qualità. |

|||

|

Stock bred for any definite purpose or to fix or maintain any character or combination of characters is, properly speaking, standard bred. The Standard of Perfection is a handbook for judges and exhibitors rather than a complete guide for breeders; for, although the breeder’s object is to produce birds of the descriptions the Standard calls for, in all varieties many birds of great value as breeders are found which the Standard disqualifies for exhibition, while in every variety in which double matings are used the exhibition type is regularly produced from matings of Standard birds of one sex with non-Standard birds of the opposite sex. |

Un gruppo allevato per qualche scopo definito o per fissare o mantenere qualche carattere o miscela di caratteri è, opportunamente parlando, uno standard allevato. Lo Standard di Perfezione è un manuale per giudici ed espositori piuttosto che una guida completa per allevatori; in quanto, anche se lo scopo dell’allevatore è produrre uccelli delle descrizioni che lo Standard richiede, in tutte le varietà molti uccelli di grande valore sono trovati come allevatori che lo Standard squalifica per l’esposizione, mentre in ogni varietà nella quale sono usati duplici accoppiamenti il tipo da esposizione è regolarmente prodotto da accoppiamenti di uccelli Standard di un sesso con uccelli non Standard del sesso opposto. |

|||

|

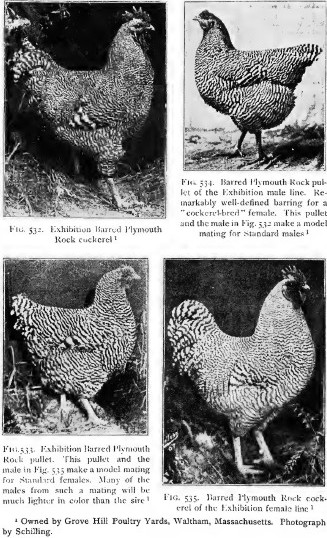

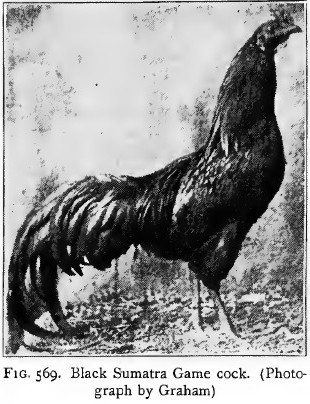

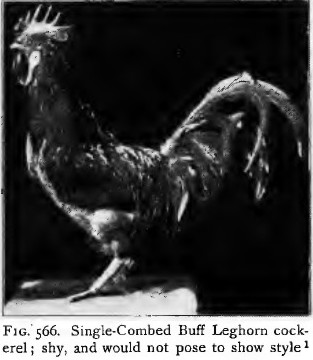

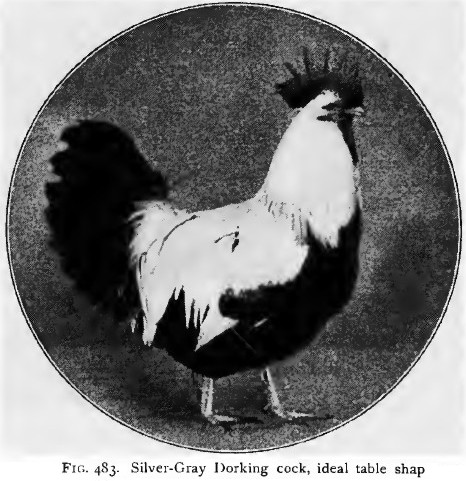

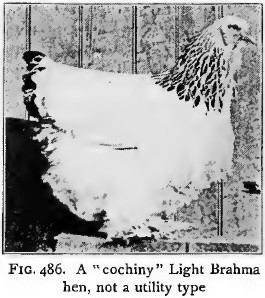

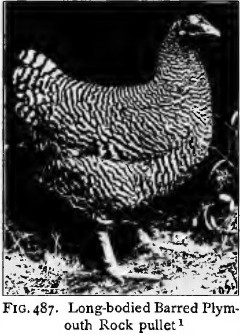

Relative value of characters in selection. When fowls are bred for eggs, without special attention to increase of egg production, there are only two essential points to be considered, ― vitality (vigor, good constitution, and development) and size, and in respect to the latter point, all that is necessary is that the fowls shall be large enough to lay eggs of the average size that the market demands. All other points may be disregarded. In breeding for the table, shape also must be considered, making vitality, size, and shape the essential points. In breeding for exhibition, carriage, color, comb, crest, and other superficial features become of importance. In applying standards in accordance with the original and rational intent of the written standard, superficial characters are not given valuations which make it possible for a bird inferior in substantial characters to win by superiority in superficial characters, and especially not by exaggeration of valuation of a single character. The common effect of the use of written, accurate standards is to bring a variety quickly to a high state of development in superficial characters. After this stage has been reached and the birds (with the usual slight individual variations) are actually of very uniform quality (on a fair interpretation of the terms describing the various [481] sections), the tendency is to make the decision of relative merits turn on a few special features, to overvalue such features, and so, by corresponding undervaluation of other features, to develop a few favored characters at the expense of the rest. Many illustrations of this kind might be given. There is hardly a variety in the Standard that has not at some time suffered through such partiality for some character. The most marked cases are those in which the variety has lost popularity through the development of a feature which finally became detrimental; but the evil is by no means confined to such. The craze for dead-white plumage for a time made the white varieties conspicuous for lack of shape and vitality. The craze for barring "to the skin" leads breeders of Barred Plymouth Rocks to some neglect of shape and size. In Leghorns and Polish the head points have been rated as high as thirty per cent of the value of the specimen, with the result, in case of the Leghorn, of so reducing size and neglecting shape of body that the breed seemed at one time in danger of losing standing with the public. In breeding birds for exhibition the breeder is forced to follow prevailing fads. Doing so does not necessarily compel neglect of other characters, but as the fad develops it becomes more and more difficult to find and produce specimens good in the favored section and also in other sections. |

Valore relativo dei caratteri in selezione . Quando i polli sono allevati per le uova, senza un’attenzione speciale per un aumento della produzione di uova, ci sono solo 2 punti essenziali da essere considerati ― vitalità (vigore, buona costituzione, e sviluppo) e dimensione, e riguardo al secondo punto, tutto ciò che è necessario è che i polli siano grandi abbastanza per deporre uova della dimensione media che il mercato richiede. Tutti gli altri punti possono essere trascurati. Nell’allevare per la tavola deve essere considerata anche la forma, considerando punti essenziali la vitalità, la taglia e la forma. Nell’allevare per l’esposizione, diventano d’importanza portamento, colore, cresta, ciuffo e altre caratteristiche superficiali. Nell’applicare gli standard in accordo con l’intento originale e razionale dello standard scritto, i caratteri superficiali non sono considerati valutazioni che lo rendono possibile per un uccello inferiore in caratteri sostanziali per vincere con superiorità in caratteri superficiali, e specialmente non con esagerazione della valutazione di un singolo carattere. L’effetto comune dell’uso di standard scritti, accurati, è il portare rapidamente una varietà a un alto grado di sviluppo in caratteri superficiali. Dopo che questo stadio è stato raggiunto e gli uccelli (con le solite lievi variazioni individuali) sono davvero di molta qualità uniforme (su un’interpretazione equa dei termini che descrivono le varie sezioni), la tendenza è prendere la decisione che i meriti relativi accendano alcune caratteristiche speciali, per sopravalutare tali caratteristiche, e così, corrispondendo una sottovalutazione di altre caratteristiche, sviluppare alcuni caratteri favoriti a spesa del resto. Potrebbero essere date molte illustrazioni di questo tipo. C’è appena una varietà nello Standard che non ha talora sofferto attraverso tale parzialità per qualche carattere. I casi più marcati sono quelli in cui la varietà ha perso la popolarità attraverso lo sviluppo di una caratteristica che infine divenne dannosa; ma il male è da nessun mezzo confinato così. La mania per il piumaggio bianco spento per un certo tempo rese le varietà bianche notevoli per la mancanza di forma e vitalità. La mania per barrare "fino alle ossa" conduce gli allevatori di Plymouth Rock Barrate a una certa negligenza di forma e taglia. In Livorno e Polacca i punti principali sono stati valutati alti come 30% del valore del campione, col risultato, nel caso della Livorno, di ridurre così la taglia e trascurare forma del corpo che la razza sembrò nello stesso momento nel pericolo di perdere la buona reputazione col pubblico. Nell’allevare uccelli per l’esposizione l’allevatore è costretto a seguire i capricci prevalenti. Facendo così ovviamente non impone la negligenza di altri caratteri, ma come il capriccio si sviluppa diviene sempre più difficile trovare e produrre buoni campioni nella sezione favorita e anche in altre sezioni. |

|||

|

Systems of selection. In selecting his breeding stock a poultry breeder uses two principles, or systems, of selection, applying sometimes one, sometimes the other; thus the common method of selection is by irregular alternation of these systems. Selection by a complex standard may be (1) progressive (or particular), considering certain characters or groups of characters always in the same order, and rejecting from subsequent consideration all individuals failing to meet requirements at any stage of selection, and (2) simultaneous (or collective), in which an effort is made to consider all the more important characters collectively, balancing faults in some against merits in others. It is not practicable to apply the progressive principle to a great many characters, one by one. By a division of characters into natural groups, with separate consideration of each group and of the principal characters, and collective consideration of all but the more important characters in a group, a simple and effective working system of selection is developed. |

Sistemi di selezione . Nel selezionare il suo gruppo in allevamento, un allevatore di pollame usa due principi, o sistemi, di selezione, applicandone qualche volta uno, qualche volta un altro; così il metodo comune di selezione avviene con una irregolare alternanza di questi sistemi. Selezione in base a uno standard complesso può essere (1) progressivo (o particolare), considerando certi caratteri o gruppi di caratteri sempre nello stesso ordine, e rifiutando in base a una considerazione successiva tutti gli individui che non riescono a soddisfare i requisiti ad ogni stadio della selezione, e (2) simultaneo (o collettivo) nel quale uno sforzo è fatto per considerare collettivamente tutti i più importanti caratteri, bilanciando in alcuni i difetti contro i meriti in altri. Non è praticabile applicare il principio progressivo a moltissimi caratteri, uno alla volta. Con una suddivisione dei caratteri i gruppi naturali, con considerazione separata di ogni gruppo e dei caratteri principali, e la considerazione collettiva di tutti ma più importanti caratteri in un gruppo, un semplice ed effettivo sistema di lavoro di selezione è sviluppato. |

|||

|

[482] Division of characters for this purpose gives three classes, which may be designated as (1) essential, (2) substantial, and (3) superficial. |

La suddivisione dei caratteri per questo scopo fornisce 3 classi, che possono essere designate come (1) essenziale, (2) sostanziale e (3) superficiale. |

|||

|

Essential characters. Whatever the purpose for which poultry are bred, they should have (a) good constitution, (b) size appropriate to minimum requirements, and (c) individual symmetry. Lacking constitutional vigor, a bird is not likely to produce offspring equal to itself in other respects. The difference may not be perceptible in comparing consecutive generations, but a comparison of stock bred for several generations with care to preserve vitality, and stock in which this point has been neglected for a similar period, rarely fails to show marked deterioration in the latter. Constitution not only affects the quality of other characters but the numbers produced, the losses of stock, and so (indirectly) the methods of practice. In size the birds selected as breeders must always be large enough to produce offspring that will meet the ordinary requirements of the purpose for which the stock is bred. Stock bred for egg production must be large enough to lay eggs marketable at prices for average receipts; stock bred for market must be large enough to produce poultry that will meet at least the minimum ordinary demand. So with stock bred to sell for breeding or laying purposes, ― if the stock is vigorous and has the size required for the ordinary production of eggs and market poultry, it is salable, though deficient in many other respects; but if it lacks constitution and ordinary size, it cannot, as a rule, be profitably grown for any purpose. Individual symmetry means a symmetrical development of the individual without regard to any particular standard; there may be symmetry of parts without correspondence with any special established type. Individual symmetry implies absence of deformity. |

Caratteri essenziali . Qualunque sia lo scopo per il quale il pollame è allevato, esso dovrebbe avere (a) una buona costituzione, (b) una taglia adeguata ai minimi requisiti, e (c) un’individuale armonia di proporzioni. Se manca il vigore costituzionale, è probabile che un uccello non produca una prole uguale sotto altri aspetti. La differenza non può essere percettibile nel paragonare generazioni consecutive, ma un paragone di gruppo allevato per molte generazioni con cura di preservare la vitalità, e di gruppo in cui questo punto è stato trascurato per un periodo simile, raramente non riesce a mostrare il marcato deterioramento nel secondo. La costituzione non solo colpisce la qualità di altri caratteri ma i numeri prodotti, le perdite di gruppo, e così (indirettamente) i metodi di pratica. In taglia gli uccelli selezionati come riproduttori devono essere sempre grandi abbastanza da produrre una prole che soddisferà i requisiti all’ordine del giorno dello scopo per cui il gruppo è allevato. Un gruppo allevato per la produzione di uova deve essere grande abbastanza da deporre uova commerciabili a prezzi per introiti medi; un gruppo allevato per il mercato deve essere grande abbastanza da produrre pollame che soddisferà almeno la minima ordinaria richiesta. Quindi con un gruppo allevato per essere venduto a scopi di allevamento o di ovo deposizione ― se il gruppo è vigoroso e ha la taglia richiesta per l’abituale produzione di uova e di pollame da mercato, è vendibile, sebbene deficiente sotto molti altri aspetti; ma se manca di costituzione e taglia all’ordine del giorno, non può, come regola, essere allevato proficuamente per qualunque scopo. La simmetria individuale significa uno sviluppo simmetrico dell’individuo senza riguardo ad alcun particolare standard; ci può essere simmetria di parti senza corrispondenza con alcun tipo stabilito speciale. La simmetria individuale implica assenza di deformità. |

|||

|

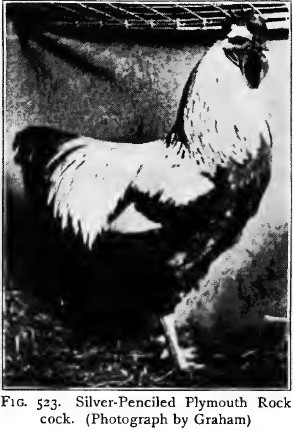

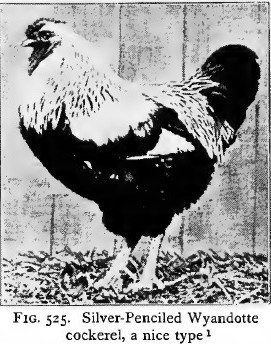

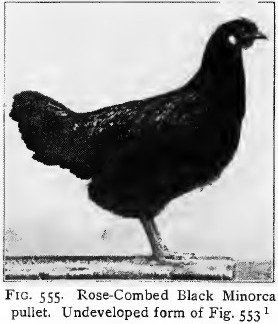

Substantial characters. Size as related to special uses or standards, and distinctive shape and color, are substantial characters. If a particular size of market poultry is to be produced, the birds used for breeders must be of appropriate size. In breeding birds, of any established race, to be sold for exhibition or breeding purposes, the breeders selected must closely approximate the standards of weight for their breed or variety. They should also have the distinctive shape and symmetry of the breed or variety, both as to body and as to the general size and shape of other parts in which characters are distinctive. Color, too, is a substantial character in so far as it may [483] have an influence on profits with poultry of no particular color type, or may qualify a specimen as of some particular color type. In breeding for market the breeder, as a rule, avoids black and dark-colored birds, especially if they are to be dressed and sold before maturity. In breeding to color standards (even without close attention to the finer points of color) a line must be drawn between color faults which may be tolerated and those which ought to condemn a bird for breeding purposes. |

Caratteri sostanziali . La taglia in relazione a usi speciali o standard, e la forma e il colore peculiari, sono caratteri sostanziali. Se una particolare taglia di un pollame da mercato deve essere prodotta, gli uccelli usati per allevare devono essere di taglia appropriata. Nell’allevare uccelli, di qualunque razza stabilita, per essere venduti per l’esposizione o per scopi di allevamento, gli allevatori selezionati debbono strettamente avvicinarsi agli standard di peso per la loro razza o varietà. Dovrebbero anche avere la forma distintiva e la simmetria della razza o varietà sia per il corpo che per la taglia generale e la forma di altre parti nelle quali i caratteri sono distintivi. Il colore è pure un carattere sostanziale in quanto può avere un’influenza su profitti con pollame di nessun particolare tipo di colore, o può qualificare un campione come di qualche particolare tipo di colore. Nell’allevare per il mercato l’allevatore, come regola, evita uccelli neri e di colore scuro, specialmente se devono essere preparati e venduti prima della maturità. Nell’allevare per degli standard di colore (anche senza un stretta attenzione per i punti più eccellenti di colore) una linea deve essere ottenuta tra difetti di colore che possono essere tollerati e quelli che dovrebbero condannare un uccello per scopi di allevamento. |

|||

|

Superficial characters. The fine points of color and of shape, particularly of shape as not affecting any useful quality, are superficial characters. It is the superficial points which make the differences between those individual specimens of a race that are worth consideration for exhibition or breeding purposes, ― which give to the specimen finish and proportionately increasing money value, provided these superficial characters are found with the desired essential and substantial characters. Remarkable finish in color or in some other conspicuous feature is often found on birds of poor shape, or distinctly inferior in size, or lacking in constitution. Such birds are not usually salable at high prices, but the breeder is strongly tempted to use them, in the hope of getting a proportion of offspring with their excellence and without their faults. An experienced breeder who knows his stock thoroughly, who relies on other matings for most of his stock, and who uses such birds only in special matings may sometimes succeed in doing this. A novice rarely gets the desired results, and if (as is too often the case) the use of such a bird for breeding affects a large part of the produce of a season, he may lose more than he could possibly gain if the bird bred up to his expectations; for a bird of this kind rarely impresses its good quality on any considerable proportion of its offspring. |

Caratteri superficiali. I raffinati punti di colore e di forma, particolarmente di forma come non pertinenti ad alcuna qualità utile, sono caratteri superficiali. Sono i punti superficiali che fanno le differenze tra quei campioni individuali di una razza che sono di valida considerazione per l’esposizione o per scopi di allevamento ― che danno alla specie raffinatezza e valore in soldi proporzionatamente in aumento, purché questi caratteri superficiali siano trovati coi caratteri essenziali e sostanziali desiderati. Straordinaria raffinatezza in colore o in qualche altra caratteristica evidente è spesso trovata su uccelli di forma povera, o nettamente inferiori in taglia, o mancanti di costituzione. Tali uccelli non sono di solito vendibili a prezzi alti, ma l’allevatore è fortemente tentato a usarli, nella speranza di trovare una proporzione di discendenza con la loro eccellenza e senza i loro difetti. Un allevatore esperto che conosce completamente il suo gruppo, che conta su altri accoppiamenti per la maggior parte del suo gruppo, e che usa tali uccelli solo in accoppiamenti speciali, può qualche volta riuscire nel fare questo. Un novizio raramente consegue i risultati desiderati, e se (come è troppo spesso il caso) l’uso di tale uccello per allevare colpisce una gran parte della produzione di una stagione, lui può perdere più di quello che possibilmente potrebbe guadagnare se l’uccello si accoppiasse secondo le sue aspettative; in quanto un uccello di questo tipo raramente applica la sua buona qualità in qualche considerevole proporzione della sua prole. |

|||

|

Progressive selection, with the elimination, at each step, of all individuals which fail in the requirements under consideration, prevents the development of stocks strong in some fancy points but lacking in essential and substantial characters. The more rigid the selection, the smaller becomes the number of birds that will pass it. As a matter of business policy the breeder must so regulate his selection of available stock that he can make the most profitable use of it as a whole, but to establish himself firmly as a breeder [484] he must make the best possible use of the relatively small proportion of each year’s produce in which he finds combined a high degree of excellence in many characters. |

La selezione progressiva, con l’eliminazione, a ogni passo, di tutti gli individui che mancano dei requisiti in considerazione, previene lo sviluppo di gruppi forti in alcuni punti di razza scelta ma che mancano di caratteri essenziali e sostanziali. Quanto più è rigida la selezione, tanto più piccolo diventa il numero di uccelli che la passeranno. Come una questione di indirizzo di affari l’allevatore deve regolare così la sua selezione di gruppo disponibile che lui può farne il suo uso più proficuo nell’insieme, ma per stabilirsi decisamente come un allevatore deve fare il migliore uso possibile della relativamente piccola proporzione della produzione di ogni anno nella quale lui trova combinato un alto grado di eccellenza in molti caratteri. |

|||

|

Collective selection and compensation in breeding. Progressive selection can apply in practice to only a few of the more important characters. It is in effect selection for the elimination of faults which the breeder regards as intolerable. When birds with such faults have been eliminated, what remain will always show considerable variation, and this will be most marked in superficial characters. Continued careful breeding reduces differences, but since at the same time it develops the breeder’s critical faculty and his ability to distinguish slight differences, the proportion of what he considers good breeders in his stock may not be materially changed. There is usually a tendency, partly in the stock and partly in the breeder’s selection, to develop a stock in the direction of its strongest points. The most effective checks on this are the written standard, competition, and the difficulty of selling specimens which are decidedly weak in any superficial character. |

Selezione collettiva e compensazione nell’allevare. La selezione progressiva si può applicare in pratica solo ad alcuni dei più importanti caratteri. È in effetti una selezione per l’eliminazione di difetti che l’allevatore ritiene intollerabili. Quando uccelli con tali difetti sono stati eliminati, ciò che rimane mostrerà sempre una variazione considerevole, e questo sarà più marcato in caratteri superficiali. Un allevamento continuato accurato riduce le differenze, ma siccome allo stesso tempo sviluppa la facoltà critica dell’allevatore e la sua abilità nel distinguere lievi differenze, la proporzione di quello che lui considera buoni allevatori nel suo gruppo non può essere materialmente cambiata. C’è di solito una tendenza, in parte nel gruppo e in parte nella selezione dell’allevatore, a sviluppare un gruppo nella direzione dei suoi punti più forti. I controlli più effettivi su ciò sono lo standard scritto, la competizione e la difficoltà di vendere campioni che sono chiaramente deboli in qualche carattere superficiale. |

|||

|

Having eliminated the most unlike individuals by progressive selection, the breeder proceeds to make appropriate matings of those he has reserved by collective consideration not simply of the points of the individual but of the points of a pair, male and female. His object is to secure in the sexes, as far as possible, likeness to the type to be produced (sexual differences of color, etc. duly considered), and when the bird of one sex varies from the typical in any character, to secure in the other sex the opposite variation in that character, nearly all variations in well-bred birds being slight when compared with variations in specimens from parents markedly unlike. This balancing of opposite tendencies in variation is of little use, as a rule, when the characters considered represent wide variations, for the result of the union of such characters is likely to give many intermediate grades of blending of characters and only a very few of any desired grade. The mating of individuals differing widely in any character is good practice only when the desired character cannot be secured by breeding together like individuals. The object of the compensation method in mating is not to enable the breeder to use for breeding purposes as large a proportion of his stock as possible, but to enable him to equalize the tendencies [485] to variation in the individuals nearest the type. A skilled breeder never uses, in his regular matings of an established variety, birds varying conspicuously from the type which produces the standard type. Experience shows that, when the object is to produce uniformity of type and high average merit, the most reliable breeders are those individuals with the fewest faults. The "good all-round bird" is almost invariably more valuable as a breeder than the bird conspicuous for special excellence of one character or a few characters. |

Avendo eliminato i più diversi individui con una selezione progressiva, l’allevatore procede a fare adatti accoppiamenti di quelli che lui ha riservato con una considerazione collettiva non semplicemente dei punti dell’individuo ma dei punti di una coppia, maschio e femmina. Il suo scopo è assicurare nei sessi, per quanto possibile, la somiglianza al tipo da essere prodotto (le differenze sessuali di colore, ecc., debitamente considerate), e quando l’uccello di un sesso varia dal tipico in qualche carattere, assicurare nell’altro sesso la variazione opposta in quel carattere, quasi tutte le variazioni negli uccelli bene allevati essendo lievi quando paragonate con variazioni in campioni marcatamente diversi dai genitori. Questo bilanciamento di tendenze opposte nella variazione è di piccolo uso, come regola, quando i caratteri considerati rappresentano ampie variazioni, in quanto il risultato dell’unione di tali caratteri è probabile che dia molti gradi intermedi di mescolanza di caratteri e solo molto poco di qualche grado desiderato. L’accoppiamento di individui che differiscono ampiamente in qualche carattere è una buona pratica solo quando il carattere desiderato non può essere assicurato facendo accoppiare tali individui. L’oggetto del metodo di compensazione nell’accoppiare è non abilitare l’allevatore a usare per scopi di allevamento una proporzione del suo gruppo più grande possibile, ma abilitarlo a pareggiare le tendenze alla variazione negli individui più vicini al tipo. Un allevatore specializzato non usa mai, nei suoi accoppiamenti regolari di una varietà stabilita, uccelli che variano in modo cospicuo dal tipo che produce il tipo standard. L’esperienza mostra che, quando lo scopo è produrre un’uniformità di tipo e un merito di alta quotazione, i riproduttori più affidabili sono quelli con il minor numero di difetti. Il "buon uccello completo" è quasi invariabilmente più prezioso come riproduttore rispetto all’uccello notevole per eccellenza speciale di un carattere o pochi caratteri. |

|||

|

Inbreeding and line breeding. Inbreeding refers to matings of individuals that are near akin. Line breeding is applied to various plans designed to conserve blood and race character without inbreeding. Theoretically, plans of breeding may be, and have been, worked out which would give the breeder, for use at frequent intervals, individuals bred in the same way from the same origin, ― the same blood separated by several generations. Possibly the specifications could be carried out in practice, but the work is too complicated and the results are too uncertain, and experience in close breeding soon shows the breeder that it is not necessary to resort to such methods to avoid inbreeding. |

L’inincrocio e l’incrocio tra poco consanguinei . L’inincrocio si riferisce ad accoppiamenti di individui che sono prossimi alla consanguineità. L’incrocio tra scarsamente consanguinei è applicato a vari progetti elaborati per conservare sangue e carattere di razza senza inincrocio. Teoreticamente i progetti di incrocio possono essere e sono stati attuati come vorrebbe fare l’allevatore, per un uso ad intervalli frequenti di individui incrociati nello stesso modo dalla stessa origine ― lo stesso sangue suddiviso da molte generazioni. Possibilmente le specificazioni potrebbero essere eseguite in pratica, ma il lavoro è assai complicato e i risultati sono troppo incerti, e l’esperienza in incroci stretti mostra all’allevatore che non è necessario ricorrere a tali metodi per evitare l’inincrocio. |

|||

|

The most common form of line breeding is to maintain a male line intact, though occasional or even regular changes are made in the female line. Such line breeding gives better results than when breeding lines are crossed and recrossed irregularly. If the head of the line was an exceptional bird, and his male descendants used for breeding in each generation resemble him very closely, the type cannot fail to be strongly impressed on the stock, though females of somewhat different breeding are occasionally used. In most cases, when results of line breeding are conspicuously and regularly good, the breeder practices close breeding to a much greater extent than he thinks it wise to admit to a public with a prejudice against it. |

La forma più comune di incrocio tra poco consanguinei è mantenere una linea maschile intatta, sebbene cambiamenti occasionali o anche regolari sono fatti nella linea femminile. Tale incrocio tra poco consanguinei dà migliori risultati di quando l’incrocio tra poco consanguinei è fatto e rifatto irregolarmente. Se alla testa dell’incrocio ci fosse un uccello eccezionale, e i suoi discendenti maschi usati per incrociare in ogni generazione gli assomigliano molto da vicino, il tipo non può fallire ad essere fortemente impressionato sul gruppo, sebbene femmine di qualche diverso incrocio siano usate di quando in quando. In più casi, quando i risultati di incrocio tra poco consanguinei sono assai e regolarmente buoni, l’allevatore pratica uno stretto accoppiamento ad un’estensione molto più grande di quanto lui pensa saggio ammettere a un pubblico con un pregiudizio contro di esso. |

|||

|

Close breeding. The term "close breeding" describes the practice of the best poultry breeders more comprehensively than the more familiar terms "line breeding" and "inbreeding." Close breeding is necessary to secure such likeness in parents that similar uniformity may be produced in their offspring. Since an individual inherits, on the average, only one half of its characters [486] from its immediate parents, 6.25 per cent from each of four grandparents, 1.50 per cent from each of eight great-grandparents, and .39 per cent from each of sixteen great-great-grandparents, it is plain that if a breeder undertakes (as most breeders do at the outset) to avoid consanguineous matings, he will always have in the ancestry of each generation of stock so many chances for reversion and recombinations of latent characters that his stock will never reach a high grade of excellence in many qualities. |

Incrocio stretto . Il termine "incrocio stretto" descrive la pratica dei migliori allevatori di pollame in modo più esauriente rispetto ai termini più familiari "incrocio tra poco consanguinei" e "inincrocio". Un incrocio stretto è necessario per assicurare tale somiglianza in genitori la cui simile uniformità può essere prodotta nei loro discendenti. Dal momento che un individuo eredita, in media, solo uno la metà dei suoi caratteri dai suoi immediati genitori, il 6,25% da ognuno dei 4 nonni, l’1,5% da ognuno degli 8 bisnonni, e lo 0,39% da ognuno dei 16 trisnonni, è chiaro che se un allevatore intraprende (come la maggior parte degli allevatori fa all’inizio) per evitare accoppiamenti tra consanguinei, lui avrà sempre nell’ascendenza di ogni generazione di gruppo così tante opportunità per reversione e ricombinazioni di caratteri latenti che il suo gruppo non giungerà mai a un alto grado di eccellenza in molte qualità. |

|||

|

In selecting like parents for any generation the breeder usually finds that the birds most like in appearance (and generally in performance as well) are of near kin, ― that is, they are like in ancestry as well as in appearance. The advantage of mating like birds of like ancestry is so plain, and has been demonstrated so often in practice, that it is universally recognized. But there is a popular belief that close breeding (in-and-in-breeding), while of advantage to the fancier, is almost immediately destructive of vitality and of practical qualities, and quickly leads to sterility. This fallacy is less prevalent than it has been, and would soon disappear from among poultrymen if breeders did not, as a matter of policy, say as little as possible about this part of their breeding practice.* |

Nel selezionare come genitori per qualche generazione l’allevatore di solito trova che gli uccelli più simili in aspetto (e generalmente anche in prestazioni) sono di ceppo vicino ― ovvero, sono simili in ascendenza così come in aspetto. Il vantaggio di accoppiare tali uccelli di ascendenza uguale è così semplice, ed è stato dimostrato così spesso in pratica che è riconosciuto universalmente. Ma c’è una credenza popolare che un incrocio stretto (incrocio ripetuto), mentre è di vantaggio per l’amatore, è quasi immediatamente distruttivo della vitalità e delle qualità pratiche, e rapidamente porta alla sterilità. Questa fallacia è meno comune di quanto è stata, e scomparirebbe presto fra gli uomini del pollame se gli allevatori non dicessero, come una questione di politica, il meno possibile su questa parte della loro pratica di allevamento.* |

|||

|

* The poultry breeder’s ordinary and low-priced stock is bought mostly by novices who insist on having stock not akin. A large breeder making many matings can furnish birds mated for breeding that are not near kin. The purchaser would usually get good results from a mating of this kind. But in a great many cases, so fearful is he of the dangers of inbreeding, and so distrustful of the breeder, that he buys from two different breeders at the same time and changes the males, or if he has some stock of his own, mates some of his females to the male purchased and one of his males to the females. An expert breeder who knew all the stock might do this with a specific object and get the results sought, but one who has no reason for a mating except to avoid inbreeding seldom gets good results from such changes. |

* Il gruppo ordinario e di basso prezzo dell’allevatore di pollame è comprato sopratutto da novizi che insistono nell’avere un gruppo non consanguineo. Un grande allevatore che fa molti accoppiamenti può fornire uccelli accoppiati da incrociare che non sono di ceppo vicino. L’acquirente otterrebbe di solito buoni risultati da un accoppiamento di questo tipo. Ma in moltissimi casi lui è così timoroso dei pericoli di incrocio, e così diffidente dell’allevatore, che compra da 2 diversi allevatori allo stesso tempo e cambia i maschi, o se lui ha qualche suo gruppo, accoppia alcune delle sue femmine col maschio acquistato e uno dei suoi maschi con le femmine. Un allevatore esperto che conosceva tutto il gruppo potrebbe fare ciò con uno specifico fine e otterrebbe i risultati ricercati, ma uno che non ha motivo per un accoppiamento, eccetto che per evitare l’inincrocio, raramente ottiene buoni risultati da tali cambiamenti. |

|||

|

The rule of good practice. Mate the best (for the object in view) individuals available, disregarding relationship, is the general practice of skillful breeders. It makes close breeding the usual practice, and at the same time leads to the introduction of new blood in small flocks every few generations, and in large stocks at less frequent intervals. As long as a breeder’s matings within the blood lines of his own stock are giving him such breeding birds as he wants, there is no object in his going outside for new blood, but when he finds another breeder producing birds better than his [487] in any respect, unless he can make the same improvement in his own stock, he must have some of that breeder’s stock. Usually he buys stock as the easiest and surest way to get what he wants. A breeder who is working on a large scale, making ten, fifteen, twenty, or more matings of a single variety every season, can, with a little care, avoid mating birds of near kin, yet keep within the same general blood lines. Such breeders, as a rule, consider the point of relationship only as it may affect the behavior of characters in transmission. Without exception these breeders are ready buyers of birds that they think may prove useful in their breeding. The small breeder, unless he has stock of high quality, and breeds very closely, is forced to go outside often, not for new blood but for better quality. |

La regola della buona pratica . Accoppiare (per lo scopo prefissato) i migliori individui disponibili, trascurando il grado di parentela, è la pratica generale degli abili allevatori. Ciò rende l’incrocio stretto la pratica abituale, e allo stesso tempo porta all’introduzione di nuovo sangue nei piccoli gruppi ogni poche generazioni, e in grandi gruppi ad intervalli meno frequenti. Finché gli accoppiamenti di un allevatore all’interno delle linee di sangue del suo proprio gruppo stanno dandogli tali uccelli d’allevamento come lui vuole, non c’è motivo nel suo andare fuori per sangue nuovo, ma quando lui trova un altro allevatore che produce uccelli migliori dei suoi in ogni aspetto, a meno che lui possa fare lo stesso miglioramento nel suo proprio gruppo, lui deve avere qualcuno di tale gruppo dell’allevatore. Di solito lui compra il gruppo come modo più facile e più sicuro di trovare quello che vuole. Un allevatore che sta lavorando in larga scala, facendo ogni stagione 10, 15, 20 o più accoppiamenti di una sola varietà, può, con una piccola cura, evitare di accoppiare uccelli di ceppo vicino, ancora tenga all’interno delle stesse linee generali di sangue. Tali allevatori, come regola, considerano il punto di relazione solamente come può influire sul comportamento dei caratteri in trasmissione. Senza eccezione questi allevatori sono pronti acquirenti di uccelli che pensano possono dimostrarsi utili nell’essere allevati. Il piccolo allevatore, a meno che abbia un gruppo di alta qualità, e razze di sommo grado, è spesso costretto ad andare fuori, non per un nuovo sangue ma per una qualità migliore. |

|||

|

The danger of introducing new blood. In any well-bred stock the danger of deterioration through the introduction of new blood, is very much more real than any danger of deterioration through lack of new blood in stock bred with due attention to essential and substantial characters. While the point is not one easily demonstrated, there is reason to suppose that a mingling of blood lines long separated tends to bring out latent ancestral characters (more especially, the most troublesome faults of a variety). Hence, before making extensive use of a bird of different stock or of unknown breeding, an experienced breeder tries it in special matings, to find out how it will "nick" with his stock. A breeder may try a bird in this way a number of times with different mates without getting the results he wants. Small breeders, even after a good deal of experience, are too prone to take chances on a new bird that has taken their fancy in their general matings, often with the result that faults requiring years of careful breeding to eliminate crop out all through the progeny. The experienced breeder never relies on a new bird until he has tested it, and never lets a bird of proved breeding value go unless he has a better one for its place. |

Il pericolo di introdurre nuovo sangue . In ogni gruppo ben allevato il pericolo del deterioramento attraverso l’introduzione di nuovo sangue è assai più reale di ogni pericolo di deterioramento attraverso la mancanza di nuovo sangue in un gruppo allevato con la dovuta attenzione per caratteri essenziali e sostanziali. Mentre il punto non è facilmente dimostrato, c’è ragione di supporre che un mescolamento di linee di sangue molto separate tende a rivelare caratteri ancestrali latenti (più particolarmente, i difetti più fastidiosi di una varietà). Per cui, prima di fare un esteso uso di un uccello di gruppo diverso o di allevamento ignoto, un allevatore esperto lo prova in speciali accoppiamenti, per scoprire come "intaccherà" il suo gruppo. Un allevatore può provare un uccello in questo modo un numero di volte con accoppiamenti diversi senza raggiungere i risultati che lui vuole. Piccoli allevatori, anche dopo una gran quantità di esperienza, sono assai inclini a rischiare su un nuovo uccello che ha ghermito la loro voglia nei loro accoppiamenti generali, spesso col risultato di difetti che richiedono anni di procreazione accurata per eliminare il raccolto fuori di tutto attraverso la progenie. L’allevatore esperto non conta mai su un nuovo uccello finché non l’ha saggiato, e mai permette a un uccello di comprovato valore di allevamento di andare avanti se lui non ne ha uno migliore per il suo luogo. |

|||

|

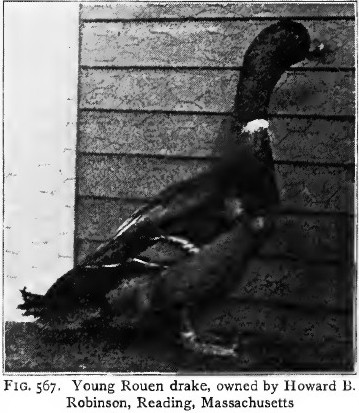

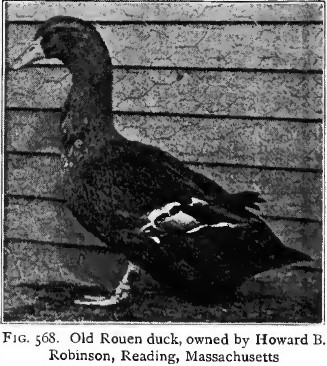

Age and breeding quality. In those kinds of poultry which get their full growth within a year, it is commonly observed that the birds, if matured by the beginning of the breeding season, are more reliable breeders the first season than afterwards, producing more young, though the quality may be somewhat inferior to what the [488] same birds produce in their second and third breeding seasons. In the larger kinds, as geese and turkeys, the yearling males in particular lack development and the two- and three-year-old males are usually in every way much better breeders. With regard to fowls and ducks ― especially the former ― many instances of great breeding vigor after the first year show that the common failure is due to conditions and management. Males are overworked during the breeding season and not given proper care after it. While old cocks are usually much less fertile in winter than cockerels, if in equally good condition they are as serviceable when spring approaches and will get larger and more uniform chickens. In general this is true also as to pullets and hens. It is largely a question of condition. The older the bird grows, the more difficult it is to keep it in good breeding condition. Few fowls and ducks are as good breeders the third year as the second, fewer still are good after the third year; yet occasionally four- and five-year-old birds of both sexes will breed as well and the hens lay as well as young stock, and there are authentic instances of fowls breeding well at seven and eight years of age. |

Età e qualità di allevamento . In quei tipi di pollame che assumono la loro piena crescita entro un anno, è comunemente osservato che i soggetti, se maturati dall’inizio della stagione degli accoppiamenti, sono generatori più affidabili nella prima stagione che dopo, producendo più giovani, sebbene la qualità può essere piuttosto inferiore a quella che gli stessi uccelli producono nelle loro seconde e terze stagioni di accoppiamenti. Nei generi più grandi, come oche e tacchini, i maschi di un anno mancano in particolare di sviluppo e i maschi di 2 e 3 anni sono di solito in ogni modo generatori molto migliori. A proposito di polli e anatre ― specialmente i primi ― molti esempi di grande vigore di procreazione dopo il primo anno dimostrano che il comune fallimento è dovuto alle condizioni e alla gestione. I maschi sono sovraccarichi di lavoro durante la stagione di procreazione e dopo non hanno una cura corretta. Mentre i vecchi galli di solito sono molto meno fertili in inverno rispetto ai galletti, se si trovano in una condizione ugualmente buona sono tanto utili quando la primavera si avvicina e diventeranno polli più grandi e più uniformi. In generale questo è vero anche per i pollastri e le galline. È grandemente una questione di condizione. Più vecchio l’uccello cresce, più difficile è tenerlo in buone condizioni di allevamento. Pochi polli e anatre sono buoni generatori il 3° anno come il 2°, meno ancora sono buoni dopo il 3° anno; tuttavia di quando in quando uccelli di ambo i sessi di 4 e 5 anni d’età si accoppieranno bene e le galline deporranno bene come se fossero giovani, e ci sono esempi autentici di polli che si riproducono bene a 7 e 8 anni d’età. |

|||

|

Ratio of females to males. In ordinary breeding, with quantity the first consideration, it is usual to make the mating ratio as wide as possible, mating with each male the largest number of females that can be kept with him and a satisfactory percentage of fertile eggs secured. This number varies greatly for individuals of the same variety, and also in averages for males of different classes of fowls and of different kinds of poultry. In fowls it varies notably, also, with conditions of mating. When one male is penned for the season with the same lot of females, the usual practice is to mate with a male of the small breeds, from ten to fifteen hens; with a male of the medium-sized breeds, from eight to twelve hens; with a male of the largest breeds, from six to ten hens. These are about the numbers used by fanciers and breeders who select and breed closely for general matings. In special matings the breeder mates with each male such females as closely match, in appearance and breeding, the one selected as the best mate for that male. In mating as carefully as this a breeder rarely finds more than three or four females for a pen, and frequently finds only one. To get full service from the male in such cases, he may either alternate him in [489] two small matings (the second of which is made up of females judged less desirable as mates for him but likely to produce some good birds) or mate him with females of several slightly different types and keep the eggs separate by trap-nesting the hens. When it is inconvenient to keep hens in as small flocks as ten or fifteen, many poultry keepers keep from twenty-five to thirty-five hens in a flock and use two males, alternating them at regular intervals. |

Proporzione delle femmine coi maschi . Nella riproduzione abituale, con la quantità come prima considerazione, è abituale fare la proporzione di accoppiamento più ampia possibile, accoppiando con ogni maschio il più grande numero di femmine che possono essere tenute con lui e una percentuale soddisfacente di uova fertili assicurate. Questo numero varia grandemente per individui della stessa varietà, e anche in medie per maschi di classi diverse di polli e di tipi diversi di pollame. Nei polli varia notevolmente, anche, con condizioni di accoppiamento. Quando un maschio è rinchiuso in un recinto per la stagione con lo stesso gruppo di femmine, la pratica abituale è di accoppiare con un maschio delle razze piccole da 10 a 15 galline; con un maschio delle razze di media dimensione da 8 a 12 galline; con un maschio delle razze più grandi da 6 a 10 galline. Questi riguardano i numeri usati da amatori e allevatori che selezionano e accoppiano bene per accoppiamenti generali. In accoppiamenti speciali l’allevatore accoppia con ogni maschio tali femmine come accoppia strettamente, in aspetto e allevamento, una selezionata come la migliore compagna per quel maschio. Nell’accoppiare così attentamente un allevatore trova raramente più di 3 o 4 femmine per un recinto, e frequentemente ne trova solo una. Per ottenere il pieno servizio dal maschio in tali casi, lui può o alternarsi in 2 piccoli accoppiamenti (il 2° del quale è fatto con femmine giudicate meno desiderabili come accoppiamenti per lui ma probabilmente per produrre alcuni buoni uccelli) o accoppiarsi con femmine di molti tipi lievemente diversi e tenere le uova separate in una gabbia nido per galline. Quando è fastidioso tenere le galline in piccoli gruppi come 10 o 15, molti custodi di pollame tengono da 25 a 35 galline in un gruppo e usano 2 maschi, alternandoli ad intervalli regolari. |

|||

|

When hens in large flocks are used to produce eggs for hatching, the proportion of males used is much smaller than for separate matings. With medium-sized fowls six males to one hundred females is generally considered sufficient. Good results have been reported from flocks of Asiatics with the same proportion of males. With large flocks of Leghorns the same proportion is used by many breeders, but others use a smaller proportion of males, some as low as three to one hundred hens.* |

Quando le galline in grandi gruppi sono usate per produrre uova da covare, la proporzione di maschi usata è molto più piccola che per accoppiamenti separati. Con polli di medie dimensioni 6 maschi per 100 femmine sono generalmente considerati sufficienti. Buoni risultati sono stati riportati da gruppi di Asiatici con la stessa proporzione di maschi. Coi grandi gruppi di Livorno la stessa proporzione è usata da molti allevatori, ma altri usano una più piccola quota di maschi, alcuni tanto bassa come 3 per 100 galline.* |

|||

|

* I cannot say positively that fertility runs better in the large flocks with the wider mating ratio, but reports from breeders indicate to me that it does. The fact of the very regular difference in mating ratio for separate matings and miscellaneous matings indicates more efficient service of the males under such conditions. |

* Io non posso dire positivamente che la fertilità decorre meglio nei grandi gruppi con un rapporto di accoppiamento più ampio, ma resoconti da allevatori mi indicano che lo fa. Il fatto della differenza molto regolare nel rapporto dell’accoppiare per accoppiamenti separati e accoppiamenti miscellanei indica un servizio più efficiente dei maschi sotto tali condizioni. |

|||

|

In ducks the usual mating ratio is one male to five females until warm weather (May or June); after that, one male to eight or ten females. As the males are not quarrelsome, and interfere with each other very little, breeding flocks may be of any desired number. Average flocks contain from thirty to forty breeders. In turkeys one male is mated with any number of females up to fifteen or twenty, the usual number being ten or twelve. All other kinds of poultry either pair or mate in small families. |

Nelle anatre il solito rapporto di accoppiamento è 1 maschio per 5 femmine finché fa caldo (maggio o giugno); dopo di che, 1 maschio per 8 o 10 femmine. Dato che i maschi non sono litigiosi, e interferiscono molto poco l’un l’altro, i gruppi da allevamento possono essere di qualunque numero desiderato. Gruppi di media quantità contengono da 30 a 40 soggetti. Nei tacchini un maschio è accoppiato con qualunque numero di femmine fino a 15 o 20, il numero abituale essendo 10 o 12. Tutti gli altri generi di pollame si appaiano o accoppiano in piccole famiglie. |

|||

|

Period of fertility. Fertile eggs are often obtained, on the second day after the introduction of a male, from hens previously kept in celibacy, but usually fertility from a new mating is low for a week or two, especially in cold weather. Experiments have shown that hens may continue to lay fertile eggs for nearly three weeks after separation from the male, and that the fertility is likely to be as good for a week or ten days after the removal of a male as it was while he was present. In turkeys the influence of an impregnation is said to continue for a very much longer period, but this view seems to rest on a small number of instances not very well authenticated. Accurate observation is difficult, and the roving [490] habit of the turkey makes it quite possible for females and males from different flocks to mate without the knowledge of the keeper. There is no authentic instance of the influence of impregnation continuing as long as three weeks in fowls. When birds of different varieties that have been running together are separated and mated each with its own kind, no effects of previous matings are likely to appear after a week or ten days.* The usual rule is not to use the eggs for hatching until two weeks after separation. |