Lessico

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz

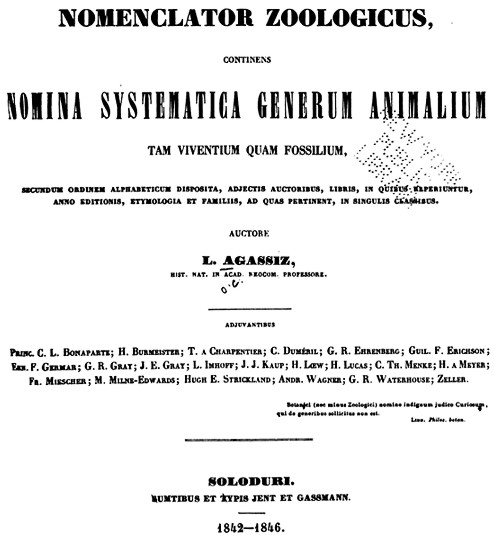

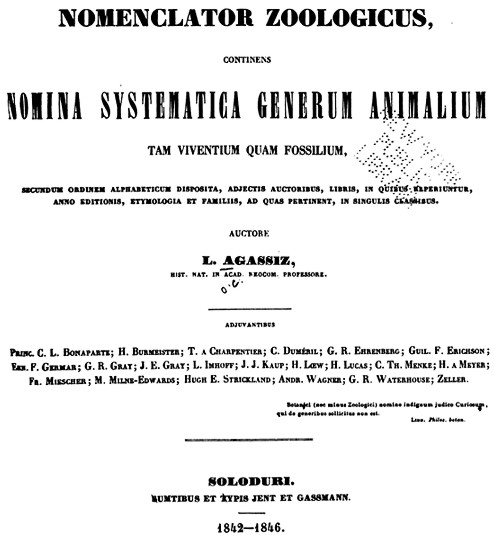

Nomenclator zoologicus

![]()

Nomenclator

zoologicus

trascrizione

e traduzione di Elio Corti![]()

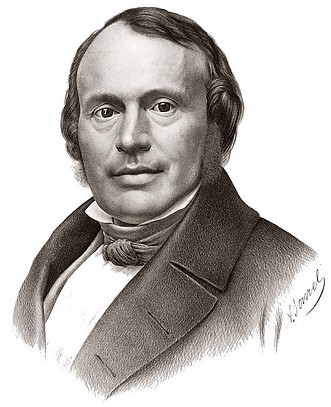

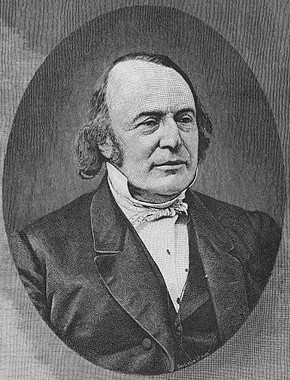

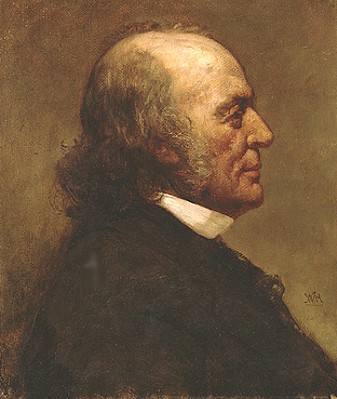

Louis Agassiz: naturalista svizzero (Môtier, Cantone di Friburgo, 1807 - Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1873). Allievo a Parigi di Georges Cuvier (naturalista e biologo francese - Montbéliard, dipartimento del Doubs 1769 - Parigi 1832), nel 1832 divenne professore di storia naturale a Neuchâtel. Nel 1846 guidò una missione scientifica negli Stati Uniti dove gli venne offerta una cattedra nell'Università di Harvard. Deve considerarsi l'iniziatore dei nuovi orientamenti naturalistici negli Stati Uniti, dove fondò il Laboratorio di Biologia Marina di Wood's Hole. Contrario all'evoluzionismo, studiò particolarmente i Pesci, i Molluschi e gli Echinodermi fossili e attuali. Si interessò inoltre a fondo dei ghiacciai lasciando sull'argomento nozioni di grande importanza; espose la sua teoria nell'opera Études sur les glaciers (1840), in cui si precisa che all'inizio dell'era quaternaria un freddo intenso invase l'emisfero settentrionale, causando bruschi cambiamenti della fauna e della flora terrestri; i mari e i laghi boreali gelarono e vaste regioni furono coperte da una spessa coltre di ghiaccio.

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (Môtier, Cantone di Friburgo, 28 maggio 1807 – Cambridge, 14 dicembre 1873) è stato un biologo, zoologo, paleontologo e ittiologo svizzero; fu anche un valente alpinista e glaciologo. Svolse gran parte della propria attività negli Stati Uniti. Sposato con l'educatrice Elizabeth Cabot Cary, fu uno dei maggiori scienziati statunitensi del suo tempo.

La formazione scolastica - Il primo anno studiò in casa, i seguenti quattro anni frequentò la scuola a Bienne/Biel (Cantone di Berna), completando, poi, il ciclo di istruzione elementare a Losanna. Inizialmente pensò di intraprendere la professione medica, ma gli accesi e passionali dibatti dei biologi dell'epoca sulla Storia Naturale degli animali, delle piante e degli esseri umani, ben presto fecero breccia nella sua immaginazione e quindi decise di iscriversi a Scienze Biologiche. Studiò nelle Università di Zurigo, Heidelberg e Monaco; in questi anni ebbe modo di approfondire le sue conoscenze di Storia Naturale, in particolar modo della botanica. Nel 1829, a Erlangen (Baviera), ottenne la laurea in Biologia e nel 1830, a Monaco, in Filosofia. Si trasferì a Parigi dove seguì gli insegnamenti di Alexander von Humboldt e Georges Cuvier, che lo incoraggiarono e lo spinsero verso la Glaciologia (la scienza che studia i ghiacciai) e la Zoologia. Fino ad allora non era stato particolarmente attratto dall'Ittiologia, che presto divenne la principale occupazione della sua vita, o almeno quella per la quale viene oggi ricordato.

Primi incarichi e pubblicazioni - Dal 1819 al 1820, Johann Baptist von Spix e Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius erano impegnati in una spedizione in Brasile e al loro ritorno in Europa, tra i molti esemplari di origine naturalistica che avevano portato a casa, c'era una serie notevole di pesci d'acqua dolce del Brasile, in particolare del Rio delle Amazzoni. Spix, che morì nel 1826, non visse abbastanza a lungo da approfondire la storia di questi pesci e Agassiz (sebbene fresco di studi scolastici) fu selezionato da Martius per questo scopo. Lui si buttò a capofitto in questa impresa con l'entusiasmo che sempre lo caratterizzò fino alla fine della sua operosa vita. Il lavoro di descrizione e classificazione dei pesci brasiliani fu completato e pubblicato nel 1829. Seguì poi una ricerca sulla storia dei pesci ritrovati nel lago di Neuchâtel. Ampliò i propri progetti producendo, nel 1830, un prospetto di Storia dei pesci d'acqua dolce nell'Europa centrale. Fu solo nel 1839, però, che la prima parte di quest'opera venne pubblicata e bisognerà aspettare il 1842 per vederne la pubblicazione completa. Nel 1832 gli fu conferita la carica di docente di Storia Naturale, presso l'Università di Neuchâtel. I pesci fossili attirarono presto la sua attenzione. Si conosceva, a quei tempi, l'abbondanza di materiale fornito dalle ardesie del Glarona (Cantone di Glarona) e dalle pietre calcaree del Monte Bolca (Monti Lessini nel comune di Vestenanova, provincia di Verona), ma non erano mai state oggetto di studi scientifici approfonditi. Agassiz, già nel 1829, progettò la pubblicazione dell'opera che, più di ogni altra, contribuì al consolidarsi della sua fama a livello mondiale. Cinque volumi della sua Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (Ricerche sui pesci fossili) furono pubblicati, a intervalli, tra il 1833 e il 1843. Questi volumi erano magnificamente illustrati, principalmente per mano di Joseph Dinkel. Durante i suoi viaggi per raccogliere materiale per il proprio lavoro, Agassiz visitò i principali musei europei e l'incontro con Cuvier a Parigi gli assicurò il suo incoraggiamento e la sua consulenza.

Agassiz scoprì che il proprio lavoro di paleontologo aveva creato le basi per una nuova classificazione ittiologica. I fossili raramente conservavano tracce di tessuti molli dei pesci. Più che altro i resti consistevano in denti, scaglie e pinne; perfino le lische venivano trovate conservate perfettamente solo in pochi casi. Agassiz perciò adottò una classificazione che divideva i pesci in quattro gruppi: Ganoidi, Placoidi, Cycloidi e Ctenoidi, basandosi sulla natura delle scaglie e di altri apparati dermici. Nonostante Agassiz abbia lavorato molto sulla classificazione scientifica, questa sarebbe stata però superata dalle opere successive.

Mentre Agassiz procedeva con il lavoro di descrizione, divenne presto evidente che questo lavoro avrebbe inciso sostanzialmente sulle sue risorse economiche, a meno che non avesse trovato un qualche tipo di finanziamento. La British Association for the Advancement of Science venne in suo aiuto e così anche il Conte di Ellesmere, allora Lord Francis Egerton. I 1.290 disegni originali che corredavano l'opera furono acquistati dal conte e da lui presentati alla Geological Society of London. Nel 1836 Agassiz ricevette la medaglia Wollaston dal Consiglio di quella Società per il suo lavoro sull'ittiologia fossile e nel 1838 fu eletto membro straniero della Royal Society. Nel frattempo cominciava a interessarsi agli invertebrati. Nel 1837 scrisse il "Prodrome" di una monografia sugli Echinodermi recenti e fossili, la prima parte della quale fu pubblicata nel 1838; dal 1839 al 1840 pubblicò due volumi sugli Echinodermi fossili della Svizzera e dal 1840 al 1845 scrisse Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles (Studi critici sui molluschi fossili).

Prima del suo viaggio in Inghilterra nel 1834, il lavoro di Hugh Miller e altri geologi portò alla luce gli straordinari pesci dell'Old Red Sandstone nel nord-est della Scozia. Le strane forme dello Pterichthys, del Coccosteus e di altre specie furono conosciute allora per la prima volta: suscitarono in Agassiz un notevole interesse e divennero l'oggetto di una speciale monografia da lui pubblicata dal 1844 al 1845: Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Gres Rouge, ou Systeme Devonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Iles Britanniques et de Russie (Monografia sui pesci fossili dell'Old Red Sandstone, o Sistema Devoniano delle isole britanniche e della Russia).

Durante i primi passi della sua carriera a Neuchâtel, Agassiz fu anche nominato direttore di una facoltà scientifica. Sotto la sua direzione l'Università di Neuchâtel divenne presto un'istituzione di primo piano per la ricerca scientifica.

Formulazione della teoria sull'era glaciale - Nel 1837 Agassiz fu il primo a proporre scientificamente l'idea che la Terra fosse stata nel passato soggetta a un'era glaciale. In passato Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, Venetz, Charpentier e altri avevano compiuto studi approfonditi sui ghiacciai delle Alpi e Charpentier era perfino giunto alla conclusione che i massi erratici di rocce alpine, disseminati sui pendii e sulle cime delle Alpi del Giura, fossero stati trasportati dagli stessi ghiacciai. La questione attirò l'attenzione di Agassiz e lui non solo fece diverse escursioni nelle regioni alpine in compagnia di Charpentier, ma costruì una capanna su uno dei ghiacciai di Aar (Svizzera), nella quale abitò per un po' di tempo per avere la possibilità di compiere delle ricerche sulla conformazione e sui movimenti del ghiaccio. Queste fatiche ebbero come risultato, nel 1840, la pubblicazione della sua opera in due volumi intitolata Études sur les glaciers (Studi sui ghiacciai). In quest'opera si discuteva dei movimenti dei ghiacciai, delle loro morene, della loro influenza sull'erosione delle rocce e sulla formazione delle striature (roches moutonnées) osservate nei paesaggi di tipo alpino. Agassiz non solo accettava l'idea di Charpentier secondo la quale alcuni ghiacciai delle Alpi si sarebbero estesi oltre le pianure e le valli per opera del fiume Aar e dal Rodano, ma si spinse oltre. Lui arrivò alla conclusione che, in un passato relativamente recente, la Svizzera sarebbe stata un'altra Groenlandia, che invece di pochi ghiacciai che occupavano le aree di interesse, un unico, enorme, strato di ghiaccio, formatosi originariamente sulle vette più alte delle Alpi, si sarebbe esteso fino a occupare l'intera vallata della Svizzera nord-occidentale, fino a raggiungere i pendii meridionali del Giura, che sebbene fossero riusciti a controllare e deviare un suo ulteriore avanzamento, non sarebbero riusciti però a impedire al ghiaccio di raggiungere in molti punti la sommità della catena montuosa. La pubblicazione di questo lavoro dette un nuovo impulso allo studio sul fenomeno dei ghiacciai in ogni parte del mondo.

Agassiz in questo modo ebbe la possibilità di avvicinarsi al fenomeno associato ai movimenti dei ghiacciai recenti e si preparò alla scoperta che fece poi nel 1840, insieme a William Buckland. I due visitarono le montagne della Scozia e scoprirono in località diverse le prove di antiche attività glaciali. La scoperta venne comunicata alla Geological Society di Londra. I distretti montani dell'Inghilterra, del Galles e dell'Irlanda furono considerati anch'essi come centri di dispersione di detriti glaciali e Agassiz sottolineò come "quegli enormi strati di ghiaccio, simili a quelli adesso esistenti in Groenlandia, una volta ricoprivano tutti i paesi nei quali si trova ghiaia non stratificata; ghiaia che generalmente veniva prodotta dalla triturazione degli strati di ghiaccio sulla superficie sottostante, etc." Dal 1842 al 1846 pubblicò a Solothurn (Solodurum in latino – capitale del cantone svizzero omonimo) il Nomenclator Zoologicus, una lista, con relativi riferimenti, di tutti i nomi, di generi e gruppi, usati in zoologia, risultato di approfondite ricerche e grande impegno.

Il trasferimento negli Stati Uniti - Con l'aiuto di una sovvenzione da parte del Re di Prussia, nell'autunno del 1846 Agassiz attraversò l'Atlantico, con lo scopo sia di occuparsi di ricerche di storia naturale e di geologia sul territorio degli Stati Uniti, che di avviare una serie di conferenze di zoologia, su invito di J. A. Lowell, al Lowell Institute di Boston, Massachusetts. I vantaggi economici e scientifici che gli furono offerti in Nord America lo indussero a stabilirsi negli Stati Uniti, dove rimase fino alla fine della propria vita. Nel 1847 fu nominato docente di zoologia e di geologia all'Università di Harvard. Nel 1852 accettò il professorato medico di anatomia comparata a Charlestown, nel Massachusetts, ma si dimise dopo due anni. Da quel momento in poi il ritmo dei suoi studi scientifici cominciò a decrescere, ma l'influenza che lui produsse in America, in entrambi i campi delle sue specializzazioni, fu profonda. Insegnò per decenni a futuri scienziati di primo piano, come David Starr Jordan, Joel Asaph Allen, Joseph Le Conte, Nathaniel Shaler, Alpheus Packard e, tra gli altri, suo figlio, Alexander Emanuel Agassiz. Il suo nome appare adesso associato a quello di diverse specie, oltre che a molti aspetti del paesaggio naturalistico americano, come il Lago Agassiz (nelle regioni centrali dell'America settentrionale), il precursore risalente al Pleistocene del Lago Winnipeg e del fiume Red River del Nord. Agassiz fu anche responsabile della costruzione del Museum of Natural History di Cambridge in Massachusetts e fu uno dei primi a studiare gli effetti dell'ultima Era Glaciale in Nord America.

Durante questo periodo Agassiz acquistò fama anche a livello popolare, diventando uno degli scienziati più famosi al mondo. Era così benvoluto che, nel 1857, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow scrisse in suo onore Il cinquantesimo compleanno di Agassiz. Agassiz scrisse ancora quattro volumi di Storia Naturale degli Stati Uniti, che furono pubblicati dal 1857 al 1862. In questi anni produsse anche un catalogo di tutti i documenti e i trattati di zoologia e geologia pubblicati fino ad allora, Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae, in quattro volumi, dal 1848 al 1854.

Nel 1860 Agassiz si ammalò, per cui decise di

ritornare 'sul campo', in parte per riposarsi, in parte per riprendere lo

studio dei pesci brasiliani. Nell'aprile del 1865 guidò una spedizione in

Brasile. Ritornò a casa nell'agosto del 1866 e il racconto di questa impresa,

intitolato Un viaggio in Brasile, fu pubblicato nel 1868. Nel 1871

organizzò una seconda escursione, visitando le spiagge meridionali del Nord

America, sia quelle sulla costa del Pacifico che dell'Atlantico.

Il suo lascito all'umanità -

Nell'ultimo periodo della sua vita lavorò per la fondazione di una sede di

formazione permanente dove gli studi zoologici potessero essere compiuti in

mezzo agli esemplari viventi oggetto di studio. Nel 1873 un filantropo

privato, John Anderson, concesse ad Agassiz l'isola di Penikese, nella baia di

Buzzard, in Massachusetts (a sud di New Bedford), e gli fece donazione di

50.000 dollari, per farne una scuola permanente di pratica di Scienze

Naturali, particolarmente dedicata allo studio di zoologia marina. La John

Anderson school crollò presto, subito dopo la morte di Agassiz, ma viene

comunque considerata l'ispiratrice del Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution,

che si trova nelle immediate vicinanze.

Agassiz viene ricordato oggi per il suo lavoro sulle ere glaciali e per essere stato uno dei maggiori zoologi a resistere alla teoria sull'evoluzione di Charles Darwin (una presa di posizione che non abbandonerà mai). Morì a Cambridge, in Massachusetts, nel 1873. Fu seppellito nel cimitero di Mount Auburn. Il suo monumento è un macigno selezionato tra le morene del ghiacciaio dell'Aar, nei pressi del vecchio Hotel des Neuchâtelois, non lontano dal posto dove un tempo aveva costruito la capanna, e gli alberi di pino che ombreggiano la sua tomba provengono dalla sua vecchia casa in Svizzera.

Oltre al Lago Agassiz e al monte Agassizhorn, hanno avuto il suo nome alcune specie animali, come l'Apistogramma agassizi (pesce della classe degli Actinopterigi), l'Isocapnia agassizi (Agassiz Snowfly, insetto esapodo), e il Gopherus agassizi (Tartaruga del deserto). Sono stati chiamati col suo nome anche un cratere su Marte edun promontorio sulla Luna.

Le Opere

Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (1833-1843)

History of the Freshwater Fishes of Central Europe (1839-1842)

Études sur les glaciers (1840)

Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles (1840-1845)

Nomenclator Zoologicus (1842-1846)

Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Gres Rouge, ou Systeme Devonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Iles Britanniques et de Russie (1844-1845)

Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae (1848)

(con Augustus Addison Gould) Principles of Zoology for the use of Schools and Colleges (Boston, 1848)

Lake Superior: Its Physical Character, Vegetation and Animals, compared with those of other and similar regions (Boston:Gould, Kendall e Lincoln, 1850)

Storia Naturale degli Stati Uniti (1847-1862)

Un viaggio in Brasile (1868)

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a paleontologist, glaciologist, geologist and a prominent innovator in the study of the Earth's natural history. He grew up in Switzerland and became a professor of natural history at University of Neuchâtel. Later, he accepted a professorship at Harvard University in the United States.

Early life and education - Louis Agassiz was born in Môtier (now part of Haut-Vully) in the canton of Fribourg, Switzerland. Educated first at home, then spending four years of secondary school in Bienne, he completed his elementary studies in Lausanne. Having adopted medicine as his profession, he studied successively at the universities of Zürich, Heidelberg and Munich; while there he extended his knowledge of natural history, especially of botany. In 1829 he received the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Erlangen, and in 1830 that of doctor of medicine at Munich. Moving to Paris he fell under the tutelage of Alexander von Humboldt and Georges Cuvier, who launched him on his careers of geology and zoology respectively. Previously he had not paid special attention to the study of ichthyology, but it soon became the great focus of his life's work.

Early work - After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, Stanford President David Starr Jordan wrote, "Somebody – Dr. Angell, perhaps – remarked that 'Agassiz was great in the abstract but not in the concrete.'" In 1819–1820, Johann Baptist von Spix and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius were engaged in an expedition to Brazil, and on their return to Europe, amongst other collections of natural objects they brought home an important set of the fresh water fish of Brazil, and especially of the Amazon River. Spix, who died in 1826, did not live long enough to work out the history of these fish, and Agassiz (though fresh out of school) was selected by Martius for this purpose. He at once threw himself into the work with an enthusiasm which characterized him to the end of his busy life. The task of describing the Brazilian fish was completed and published in 1829. This was followed by research into the history of the fish found in Lake Neuchâtel. Enlarging his plans, in 1830 he issued a prospectus of a History of the Freshwater Fish of Central Europe. It was only in 1839, however, that the first part of this publication appeared, and it was completed in 1842. In 1832 he was appointed professor of natural history in the University of Neuchâtel. The fossil fish there soon attracted his attention. The fossil-rich stones furnished by the slates of Glarus and the limestones of Monte Bolca were known at the time, but very little had been accomplished in the way of scientific study of them. Agassiz, as early as 1829, planned the publication of the work which, more than any other, laid the foundation of his worldwide fame. Five volumes of his Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (Research on Fossil Fish) appeared at intervals from 1833 to 1843. They were magnificently illustrated, chiefly by Joseph Dinkel. In gathering materials for this work Agassiz visited the principal museums in Europe, and meeting Cuvier in Paris, he received much encouragement and assistance from him. They had known him for seven years at the time.

Agassiz found that his palaeontological labours made necessary a new basis of ichthyological classification. The fossils rarely exhibited any traces of the soft tissues of fish. They consisted chiefly of the teeth, scales and fins, even the bones being perfectly preserved in comparatively few instances. He therefore adopted a classification which divided fish into four groups: Ganoids, Placoids, Cycloids and Ctenoids, based on the nature of the scales and other dermal appendages. While Agassiz did much to place the subject on a scientific basis, this classification has been superseded by later work.

As Agassiz's descriptive work proceeded, it became obvious that it would over-tax his resources unless financial assistance could be found. The British Association came to his aid, and the Earl of Ellesmere — then Lord Francis Egerton — gave him yet more efficient help. The 1,290 original drawings made for the work were purchased by the Earl, and presented by him to the Geological Society of London. In 1836 the Wollaston Medal was awarded to Agassiz by the council of that society for his work on fossil ichthyology; and in 1838 he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Society. Meanwhile invertebrate animals engaged his attention. In 1837 he issued the "Prodrome" of a monograph on the recent and fossil Echinodermata, the first part of which appeared in 1838; in 1839–40 he published two quarto volumes on the fossil Echinoderms of Switzerland; and in 1840–45 he issued his Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles (Critical Studies on Fossil Mollusks).

Before his first visit to England in 1834, the labours of Hugh Miller and other geologists brought to light the remarkable fish of the Old Red Sandstone of the northeast of Scotland. The strange forms of the Pterichthys, the Coccosteus and other genera were then made known to geologists for the first time. They were of intense interest to Agassiz, and formed the subject of a special monograph by him published in 1844–45: Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Grés Rouge, ou Système Devonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Iles Britanniques et de Russie (Monograph on Fossil Fish of the Old Red Sandstone, or Devonian System of the British Isles and of Russia). In the early stages of his career in Neuchatel, Agassiz also made a name for himself as a man who could run a scientific department well. Under his care, the University of Neuchâtel soon became a leading institution for scientific inquiry.

Proposal of an ice age - In 1837 Agassiz was the first to scientifically propose that the Earth had been subject to a past ice age. In the same year, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Prior to this proposal, Goethe, de Saussure, Venetz, Jean de Charpentier, Karl Friedrich Schimper and others had made the glaciers of the Alps the subjects of special study, and Goethe, Charpentier as well as Schimper had even arrived at the conclusion that the erratic blocks of alpine rocks scattered over the slopes and summits of the Jura Mountains had been moved there by glaciers. The question having attracted the attention of Agassiz, he not only discussed it with Charpentier and Schimper and made successive journeys to the alpine regions in company with them, but he had a hut constructed upon one of the Aar Glaciers, which for a time he made his home, in order to investigate the structure and movements of the ice. These labours resulted, in 1840, in the publication of his work in two volumes entitled Études sur les glaciers "Study on Glacier"). In it he discussed the movements of the glaciers, their moraines, their influence in grooving and rounding the rocks over which they travelled, and in producing the striations and roches moutonnees seen in Alpine-style landscapes. He not only accepted Charpentier's and Schimper's idea that some of the alpine glaciers had extended across the wide plains and valleys drained by the Aar and the Rhône, but he went still farther. He concluded that, in the relatively recent past, Switzerland had been another Greenland; that instead of a few glaciers stretching across the areas referred to, one vast sheet of ice, originating in the higher Alps, had extended over the entire valley of northwestern Switzerland until it reached the southern slopes of the Jura, which, though they checked and deflected its further extension, did not prevent the ice from reaching in many places the summit of the range. The publication of this work gave a fresh impetus to the study of glacial phenomena in all parts of the world.

Thus familiarized with the phenomena associated with the movements of recent glaciers, Agassiz was prepared for a discovery which he made in 1840, in conjunction with William Buckland. The two visited the mountains of Scotland together, and found in different locations clear evidence of ancient glacial action. The discovery was announced to the Geological Society of London in successive communications. The mountainous districts of England, Wales, and Ireland were also considered to constitute centres for the dispersion of glacial debris; and Agassiz remarked "that great sheets of ice, resembling those now existing in Greenland, once covered all the countries in which unstratified gravel (boulder drift) is found; that this gravel was in general produced by the trituration of the sheets of ice upon the subjacent surface, etc." In 1842-1846 he issued his Nomenclator Zoologicus, a classified list, with references, of all names employed in zoology for genera and groups — a work of great labour and research.

Relocation to the United States - With the aid of a grant of money from the King of Prussia, Agassiz crossed the Atlantic in the autumn of 1846 with the twin purposes of investigating the natural history and geology of North America and delivering a course of twelve lectures on “The Plan of Creation as shown in the Animal Kingdom,” by invitation from J. A. Lowell, at the Lowell Institute in Boston, Massachusetts. The financial and scientific advantages presented to him in the United States induced him to settle there, where he remained to the end of his life. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1846. His engagement for the Lowell Institute lectures precipitated the establishment of the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard University in 1847 with him as its head. Harvard appointed him professor of zoology and geology, and he founded the Museum of Comparative Zoology there in 1859 serving as the museum's first director until his death in 1873. During his tenure at Harvard, he was, among many other things, an early student of the effect of the last Ice Age on North America.

He continued his lectures for the Lowell Institute. In succeeding years, he gave series of lectures on “Ichthyology” (1847–48 season), “Comparative Embryology” (1848–49), “Functions of Life in Lower Animals” (1850–51), “Natural History” (1853–54), “Methods of Study in Natural History” (1861–62), “Glaciers and the Ice Period” (1864–65), “Brazil” (1866–67) and “Deep Sea Dredging” (1869–70).

In 1850 he married an American college teacher, Elizabeth Cabot Cary Agassiz, who later wrote introductory books about natural history and, after his death, a lengthy biography of her husband. Agassiz served as a non-resident lecturer at Cornell while also being on faculty at Harvard.[8] In 1852 he accepted a medical professorship of comparative anatomy at Charlestown, Massachusetts, but he resigned in two years. From this time his scientific studies dropped off, but he was a profound influence on the American branches of his two fields, teaching decades worth of future prominent scientists, including Alpheus Hyatt, David Starr Jordan, Joel Asaph Allen, Joseph Le Conte, Ernest Ingersoll, William James, Nathaniel Shaler, Samuel Hubbard Scudder, Alpheus Packard, and his son Alexander Agassiz, among others. He had a profound impact on the paleontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott. In return his name appears attached to several species, as well as here and there throughout the American landscape, notably Lake Agassiz, the Pleistocene precursor to Lake Winnipeg and the Red River.

During this time he grew in fame even in the public consciousness, becoming one of the best-known scientists in the world. By 1857 he was so well-loved that his friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote "The fiftieth birthday of Agassiz" in his honor. His own writing continued with four (of a planned ten) volumes of Natural History of the United States which were published from 1857 to 1862. During this time he also published a catalogue of papers in his field, Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae, in four volumes between 1848 and 1854.

Stricken by ill health in the 1860s, he resolved to return to the field for relaxation and to resume his studies of Brazilian fish. In April 1865 he led a party to Brazil. Returning home in August 1866, an account of this expedition, entitled A Journey in Brazil, was published in 1868. In December 1871 he made a second eight month excursion, known as the Hassler expedition under the command of Commander Philip Carrigan Johnson (brother of Eastman Johnson), visiting South America on its southern Atlantic and Pacific seaboards. The ship explored the Magellan Strait, which drew the praise of Charles Darwin.

Elizabeth Aggasiz wrote, at the Strait: '…the Hassler pursued her course, past a seemingly endless panorama of mountains and forests rising into the pale regions of snow and ice, where lay glaciers in which every rift and crevasse, as well as the many cascades flowing down to join the waters beneath, could be counted as she steamed by them.... These were weeks of exquisite delight to Agassiz. The vessel often skirted the shore so closely that its geology could be studied from the deck.'

Legacies - In 1863, Agassiz's daughter Ida married Henry Lee Higginson, later to be founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and benefactor to Harvard University and other schools. On November 30, 1860, Agassiz's daughter Pauline was married to Quincy Adams Shaw (1825–1908), a wealthy Boston merchant and later benefactor to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Quincy Adams Shaw and his brother-in-law Henry Higginson became major investors in the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company, and Shaw was the first president of the company and retained that position until 1871, when Agassiz's son Alexander Agassiz took over.

In the last years of his life, Agassiz worked to establish a permanent school where zoological science could be pursued amid the living subjects of its study. In 1873, a private philanthropist (John Anderson) gave Agassiz the island of Penikese, in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts (south of New Bedford), and presented him with $50,000 to permanently endow it as a practical school of natural science, especially devoted to the study of marine zoology. The John Anderson school collapsed soon after Agassiz's death, but is considered a precursor of the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory, which is nearby.

Agassiz is remembered today for his theories on ice ages, and for his resistance to Charles Darwin's theories on evolution, which he kept up his entire life. He died in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1873 and was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery, joined later by his wife. His monument is a boulder selected from the moraine of the glacier of the Aar near the site of the old Hotel des Neuchâtelois, not far from the spot where his hut once stood; and the pine-trees that shelter his grave were sent from his old home in Switzerland.

The Cambridge elementary school north of Harvard University was named in his honor and the surrounding neighbourhood became known as "Agassiz" as a result. The school's name was changed to the Maria L. Baldwin School on May 21, 2002, in honor of the African-American principal of the school who served from 1889 until 1922. The neighbourhood, however, continues to be known as Agassiz.

An ancient glacial lake that formed in the Great Lakes region of North America, Lake Agassiz, is named after him, as are Mount Agassiz in California's Palisades, Mount Agassiz, in the Uinta Mountains, and Agassiz Peak in Arizona. Agassiz Glacier and Agassiz Creek in Glacier National Park also bear his name. A crater on Mars and a promontorium on the Moon are also named in his honour. In addition, several animal species are so named, including Apistogramma agassizi Steindachner, 1875 (Agassiz's dwarf cichlid); Isocapnia agassizi Ricker, 1943 (a stonefly); Publius agassizi (Kaup), 1871 (a passalid beetle); Xylocrius agassizi (LeConte), 1861 (a longhorn beetle); Exoprosopa agassizi Loew, 1869 (a bee fly); and the most well-known, Gopherus agassizii Cooper, 1863 (the desert tortoise).

In 2005 the EGU Division on Cryospheric Sciences established the Louis Agassiz Medal, awarded to individuals in recognition of their outstanding scientific contribution to the study of the cryosphere on Earth or elsewhere in the solar system.

He took part in a monthly gathering called the Saturday Club at the Omni Parker House, a meeting of Boston writers and intellectuals. He was therefore mentioned in a stanza of the Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. poem, "At the Saturday Club," where the author dreams he sees some of his friends who are no longer:

There, at the table's further end I see

In his old place our Poet's vis-à-vis,

The great PROFESSOR, strong, broad-shouldered, square,

In life's rich noontide, joyous, debonair.

His social hour no leaden care alloys,

His laugh rings loud and mirthful as a boy's,--

That lusty laugh the Puritan forgot,--

What ear has heard it and remembers not?

How often, halting at some wide crevasse

Amid the windings of his Alpine pass,

High up the cliffs, the climbing mountaineer,

Listening the far-off avalanche to hear,

Silent, and leaning on his steel-shod staff,

Has heard that cheery voice, that ringing laugh,

From the rude cabin whose nomadic walls

Creep with the moving glacier as it crawls!

How does vast Nature lead her living train

In ordered sequence through that spacious brain,

As in the primal hour when Adam named

The new-born tribes that young creation claimed!--

How will her realm be darkened, losing thee,

Her darling, whom we call our AGASSIZ!

Classification scheme - After Agassiz came to the United States he became a prolific writer in what has been later termed the genre of scientific racism. Agassiz was specifically a believer and advocate in polygenism, that races came from separate origins (specifically separate creations), were endowed with unequal attributes, and could be classified into specific climatic zones, in the same way he felt other animals and plants could be classified.

Agassiz was a creationist who believed nature had order because God has created it directly and Agassiz viewed his career in science for the search of ideas in the mind of the creator expressed in creation. Agassiz denied that migration and adaptation could account for the geographical age or any of the past. Adaptation took time, in an example Agassiz questioned how could plants or animals migrate through regions they were not equipped to handle.

According to Agassiz the conditions in which particular creatures live “are the conditions necessary to their maintenance, and what among organized beings is essential to their temporal existence must be at least one of the conditions under which they were created”.

In his work he noted similarities of distribution of like species in different geological era; a phenomenon clearly not the result of migration. Agassiz questioned how fish of the same species live in lakes well separated with no joining waterway, Agassiz concluded they were created at both locations. According to Agassiz the intelligent adaptation of creatures to their environments testified to an intelligent plan. The conclusions of his studies lead him to believe that whichever region each animal was found in, was created there “animals are naturally autochthones wherever they are found”. After further research he later extended this idea to humans, which became to be known as his theory of polygenesis.

According to Agassiz’s theory of polygenesis animals, plants and humans were all created in “special provinces” each having distinct populations of species created in and for that province. Agassiz claimed plants, animals and humans did not originate in pairs but were created in large numbers. According to Agassiz the different races were created in different provinces, each race was indigenous to the province it was created in, he sited evidence from Egyptian monuments to prove that fixity of racial types had existed for at least five millennia. According to Agassiz’s theory of polygenism all species are fixed, including all the races of humans and species do not evolve into other species.

Agassiz like other polygenists believed Book of Genesis recounted the origin of the White race only and that the animals and plants in the bible refer only to those species proximate and familiar to Adam and Eve. Agassiz, Josiah Clark Nott, and other polygenists such as George Gliddon, believed that the biblical Adam means "to show red in the face" or "blusher"; since only light skinned people can blush, then the biblical Adam must be the Caucasian race. Agassiz believed like many of the other polygenists that the writers of the bible only knew of local events, for example the Noah's flood was a local event only known to the regions that were populated by ancient Hebrews, Agassiz claimed the writers of the bible did not know about any events other than what was going on in their own region and their intermediate neighbors.

According to Agassiz the provinces that the different races were created in included Western American Temperate (the indigenous peoples west of the Rockies); Eastern American Temperate (east of the Rockies); Tropical Asiatic (south of the Himalayas); Temperate Asiatic (east of the Urals and north of the Himalayas); South American Temperate (South America); New Holland (Australia); Arctic (Alaska and Arctic Canada); Cape of Good Hope (South Africa); and American Tropical (Central America and the West Indies).

Stephen Jay Gould has argued that Agassiz's theories sprang from an

initial revulsion in his encounters with African-Americans upon moving to the

United States.

Even though Agassiz was a believer in polygenism he rejected racism and

supported the notion of a spiritualized human unity. He claimed human

polygenism did not undermine the spiritual commonality of all people, even

though each race was physically diverse. The physical descent was irrelevant

to the spiritual descent of humanity according to Agassiz. Agassiz also

believed God had made all men equal:

Those intellectual and moral qualities which are so eminently developed in civilized society, but which equally exist in the natural dispositions of all human races, constituting the higher unity among men, making them all equal before God.

Agassiz was never a supporter of slavery he claimed his views had nothing to do with politics. Agassiz was influenced by philosophical idealism and the scientific work of Georges Cuvier. According to Agassiz genera and species were ideas in the mind of God, their existence in God’s mind prior to their physical creation meant that God could create human as one species yet in several distinct and geographically separate acts of creation. According to Agassiz there is one species of humans but many different creations of races.

Agassiz attacked monogenism and evolution, he claimed that the theory of evolution reduced the wisdom of God to an impersonal materialism. Species in their natures and geographical distribution, are direct expressions of the intelligence and will of God not the results of blind chance according to Agassiz. Agassiz believed evolution was an insult to the wisdom and will of God.

Popular in his day was Agassiz’s theory polygenesis and was accepted by a number of Protestants and scientists. For example Nathaniel Shaler who had studied under Agassiz at Harvard was a believer in Agassiz's polygenism.

In recent years, critics have cited Agassiz's racial theories, arguing that these now-unpopular views tarnish his scientific record; this has occasionally prompted the renaming of landmarks, schoolhouses, and other institutions which bear the name of Agassiz (which abound in Massachusetts). Opinions on these events are often torn, given his extensive scientific legacy in other areas. On September 9, 2007 the Swiss government acknowledged the "racist thinking" of Agassiz but declined to rename the Agassizhorn summit.

Works

Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (1833–1843)

History of the Freshwater Fishes of Central Europe (1839–1842)

Études sur les glaciers (1840)

Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles (1840–1845)

Nomenclator Zoologicus (1842–1846)

Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Gres Rouge, ou Systeme Devonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Iles Britanniques et de Russie (1844–1845)

Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae (1848)

(with AA Gould) Principles of Zoology for the use of Schools and Colleges (Boston, 1848)

Lake Superior: Its Physical Character, Vegetation and Animals, compared with those of other and similar regions (Boston: Gould, Kendall and Lincoln, 1850)

Contributions to the natural history of the United States of America (Boston: Little, Brown, 1857–1862)

Geological Sketches (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1866)

A Journey in Brazil (1868)

De l'espèce et de la classification en zoologie [Essay on classification] (Trans. Felix Vogeli. Paris: Bailière, 1869)

Geological Sketches (Second Series) (Boston: J.R. Osgood, 1876)

Essay on Classification, by Louis Agassiz (1962, Cambridge)