Lessico

Avicenna

Nome

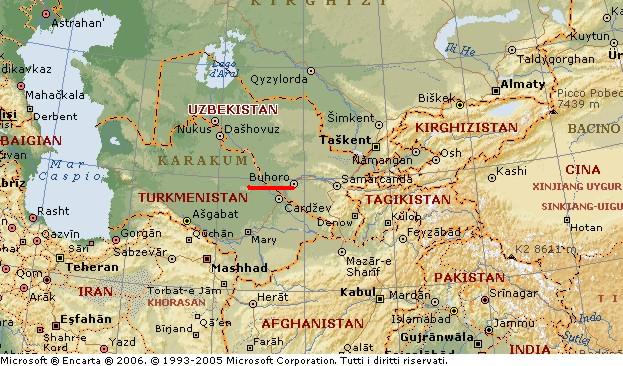

latinizzato del filosofo, medico e letterato persiano Abu Ali al-Husain Ibn

Sina (Afshana, presso Buhara/Buhoro/Buchara/Bukhara,

Uzbekistan, 980

- Hamadan![]() 1037). Figlio di un funzionario della dinastia persiana dei Samanidi,

manifestò sin da fanciullo una spiccata attitudine per gli studi filosofici e

scientifici, in particolar modo per la medicina. Attivo sostenitore del

patriottismo iraniano, fu ministro (wazir) sotto i Buwaihidi a Hamadan, ma

dopo la conquista della città da parte del sultano turco gasnavide Mahmud, si

trasferì a Esfahan, dove divenne consigliere del principe kakuyide Ala

ad-Dawlah. Morì durante una campagna per la riconquista di Hamadan.

1037). Figlio di un funzionario della dinastia persiana dei Samanidi,

manifestò sin da fanciullo una spiccata attitudine per gli studi filosofici e

scientifici, in particolar modo per la medicina. Attivo sostenitore del

patriottismo iraniano, fu ministro (wazir) sotto i Buwaihidi a Hamadan, ma

dopo la conquista della città da parte del sultano turco gasnavide Mahmud, si

trasferì a Esfahan, dove divenne consigliere del principe kakuyide Ala

ad-Dawlah. Morì durante una campagna per la riconquista di Hamadan.

Le opere specificamente filosofiche di Avicenna sono il Libro della Guarigione e il Libro della Liberazione, scritte in arabo, che era la lingua dotta dell'epoca, e il Libro della Sapienza, in persiano, un'esposizione semplificata del suo sistema filosofico, dedicata al principe Ala ad-Dawlah. In filosofia Avicenna non intese costruire un sistema originale ma, negando all'aristotelismo (che pur egli professa nel Libro della Liberazione) la qualifica di verità completa, volle limitarsi a esporre il pensiero di Aristotele come uno dei gradi della verità.

L'opera poetica persiana attribuita ad Avicenna comprende dodici quartine), un ghazal, un frammento (ma c'è chi pensa che sia l'autore di una parte del corpus di Umar Hayyam); quella prosastica è composta da alcuni affascinanti racconti allegorici. Nella quartina la riflessione lirica fa da supporto ad aforismi scettici, amari, lucidamente materialistici, più ammonitori nei riguardi delle illusioni umane che non moraleggianti nel senso usuale del termine.

Nella

medicina Avicenna è considerato uno dei massimi esponenti del periodo

migliore della scuola medica araba; in arabo scrisse i suoi studi di anatomia,

fisiologia, patologia e farmacologia, raccolti nel testo Il canone che,

tradotto in latino nel sec. XII da Gherardo da Cremona![]() col titolo di Liber

canonis medicinae o Canon medicinae e ritradotto da Andrea Alpago

col titolo di Liber

canonis medicinae o Canon medicinae e ritradotto da Andrea Alpago![]() nel sec. XV

nel sec. XV![]() , influenzò per lungo tempo la medicina europea.

, influenzò per lungo tempo la medicina europea.

Il

Canon medicinae si divide in 5 libri:

1 - della medicina teorica e pratica in generale, inclusa l'anatomia

2 - dei medicamenti semplici

3 - delle malattie particolari a una data parte del corpo

4 - delle malattie non particolari di una data parte

5 - della composizione e dell'applicazione dei medicamenti.

La medicina di Avicenna, in buona parte di derivazione galenica, appare come una costruzione unitaria paragonabile, per il rigore scientifico svincolato da influenze filosofiche, a una disciplina matematica. Avicenna ci ha lasciato anche numerosi scritti riguardanti l'astronomia, la matematica e le scienze naturali, contenuti specialmente nel Libro della Guarigione.

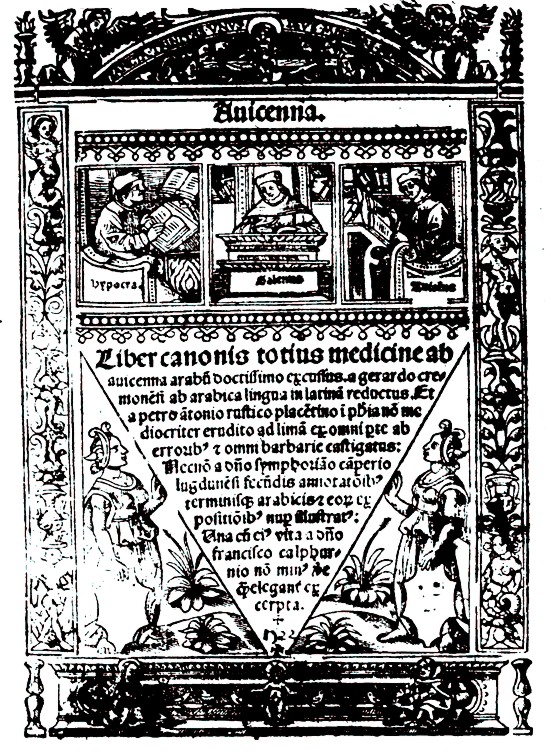

Liber canonis totius medicine

a Gerardo Cremonensi ab arabica lingua in latinam reductus

et a Petro Antonio Rustico Placentino

Symphoriano Camperio Lugdunensi secundis annotationibus

1522

Bibliografia disponibile nelle biblioteche italiane – 2005

- Compendium

de anima ... De diffinitionibus, & quaesitis. De diuisione scientiarum. Ab

Andrea Alpago ... ex Arabico in Latinum versa. Cum expositionibus eiusdem

Andreae. - Venetiis : apud Iuntas, 1546 (apud haeredes Lucaeantonii Iuntae).

- De fractura cranei caput a Ioanne Philippo Ingrassia correctum. -

[1576?].

- De vulneribus neruorum & quae currunt cursu eorum, et eorum vlceribus

a Ioanne Philippo Ingrassia correctum. - [1576?].

- Avicennae Arabum medicorum principis. Ex Gerardi Cremonensis versione, et

Andreae Alpagi castigatione. A Ioanne Costaeo, & Ioanne Paulo Mongio

annotationibus iampridem illustratus Nunc vero ab eodem

- Venetiis : apud Iuntas, 1595.

- Expositiones suo loco cum textu Auicenne alligate Gentilis Fulginei atque

Thadei Florentini in secundam seu de criticis quarti canonis. - Neapoli :

per Sigismundum Mair, 1511.

- Hic merito inscribi potens vite liber corporalis canonis libros quinque

... Doctores circa textum positi ... Gentilisde Fulgineo. Iacobus de Partibus

... Thadeusque Florentinus. - Venetijs : per Bernardinum Benalium,

1501-1503.

- Libellus de remouendis nocumentis ... ab Andrea Alpago ex Arabico in

Latinum versa. - Venetijs : apud Cominum de Tridino, 1547.

- Liber canonis. - Venetiis : per Bonetum Locatellum : impensis heredum

Octaviani Scoti, 1505.

- Liber canonis. De medicinis cordialibus. Cantica. De removendis

nocumentis ... Benedictus Rinius ... locubrationibus decoraverat. -

Venetiis : apud Iuntas, 1562 (Venetiis : apud haeredes Lucaeantonii Iuntae,

1562).

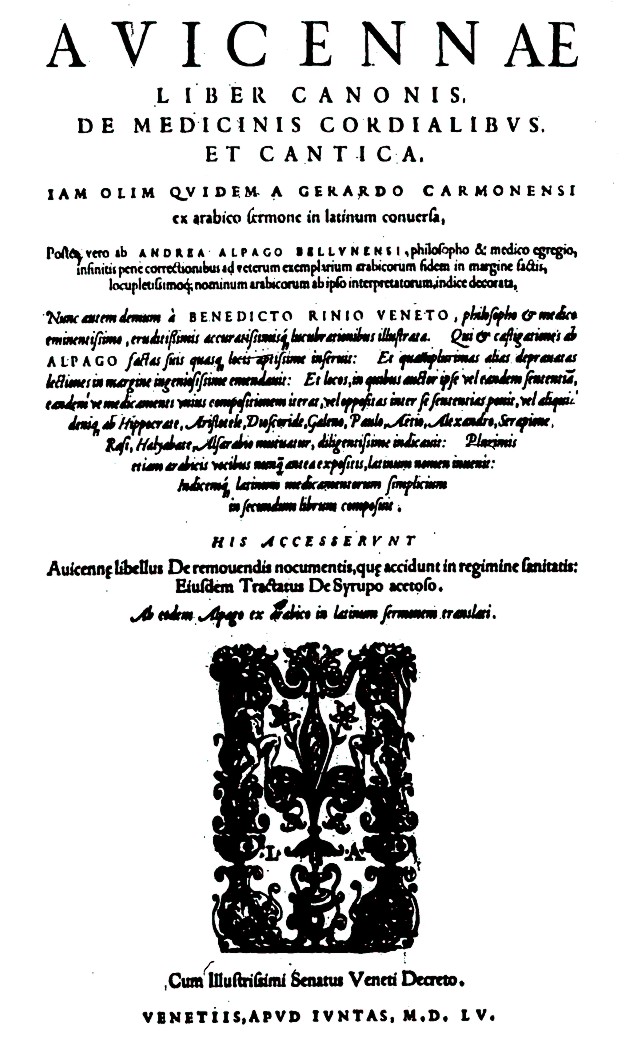

- Avicennae Liber canonis, de medicinis cordialibus, et cantica, iam olim

quidem a Gerardo Carmonensi ex Arabico sermone in Latinum conuersa, postea

vero ab Andrea Alpago Bellunensi, philosopho & medico - Venetiis :

apud Iuntas (apud haeredes Lucaeantonii Iuntae), 1555.

- Liber primus de universalibus medicae scientiae praeceptis, Andrea

Gratiolo interprete. - Venetiis : apud Franciscum Zilettum, 1580.

Avicenna

in un'immagine tratta dal Viridarium Chymicum di Stolcius de

Stolcemberg, Francoforte 1624.

L'epigramma di commento recita:

"Egli

diffuse nel mondo i segreti del magistero e frammischiò dei simboli nei suoi

scritti.

Congiungi il Rospo terrestre all'Aquila che vola, scorgerai il

magistero della nostra arte."

Il mistero delle origini dell'alchimia si riflette nei testi latini nell'uso di annoverare fra i padri dell'alchimia i più diversi personaggi celebri (mitici e storici) dell'antichità giudaico- biblica, dell'antichità cristiana, dell'antichità islamica etc.

Birth

approximately 980 CE / 370 AH

Death 1037 CE / 428 AH

School/tradition Islamic medicine

Main interests - Medicine, astronomy, alchemy, chemistry, ethics, logic, mathematics, metaphysics, philosophy, physics, poetry, science, theology

Notable ideas - The works of Avicenna were long used in Islamic and European medical education, and influenced European physicists

Influences - Aristotle, Galen, Neoplatonism, al-Farabi, al-Biruni, Muslim physicians such as al-Kindi and al-Razi

Influenced - Al-Biruni, Omar Khayyám, Averroes, Scholasticism, Albertus Magnus, Scotus, Thomas Aquinas, Buridan, Benedetti, Galileo, Jann Rañeses

Abu Ali

al-Husayn ibn Abd Allah ibn Sina, born c. 980 in Afshana near Buhara/Buhoro/Buchara/Bukhara,

Uzbekistan – died in 1037 in Hamadan![]() , the ancient Ecbatana (Persia). Commonly known in

English by his Latinized name Avicenna, was a Persian Shi'a Muslim polymath:

an astronomer, chemist, logician and mathematician, physicist and scientist,

poet, soldier and statesman, theologian, and foremost physician and

philosopher of his time.

, the ancient Ecbatana (Persia). Commonly known in

English by his Latinized name Avicenna, was a Persian Shi'a Muslim polymath:

an astronomer, chemist, logician and mathematician, physicist and scientist,

poet, soldier and statesman, theologian, and foremost physician and

philosopher of his time.

He wrote almost 450 works on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived. In particular, 150 of the surviving works concentrated on philosophy and 40 of them concentrated on medicine. His most famous works are The Book of Healing and The Canon of Medicine, which was a standard medical text at many Islamic and European universities up until the 18th century. Ibn Sina developed a medical system that combined his own personal experience with that of Islamic medicine, the medical system of Galen, Aristotelian metaphysics, and ancient Persian, Mesopotamian and Indian medicine. Ibn Sina is regarded as the father of modern medicine, particularly for his introduction of systematic experimentation and quantification into the study of physiology, his discovery of the contagious nature of infectious diseases, the introduction of quarantine to limit the spread of contagious diseases, the introduction of clinical trials, and the first descriptions on bacteria and viral organisms. He is also considered the father of the fundamental concept of momentum in physics.

George Sarton, the father of the history of science, wrote in the Introduction to the History of Science: "One of the most famous exponents of Muslim universalism and an eminent figure in Islamic learning was Ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna (981-1037). For a thousand years he has retained his original renown as one of the greatest thinkers and medical scholars in history. His most important medical works are the Qanun (Canon) and a treatise on Cardiac drugs. The 'Qanun fi-l-Tibb' is an immense encyclopedia of medicine. It contains some of the most illuminating thoughts pertaining to distinction of mediastinitis from pleurisy; contagious nature of phthisis; distribution of diseases by water and soil; careful description of skin troubles; of sexual diseases and perversions; of nervous ailments."

Early life

Ibn Sina's life is known to us from authoritative sources. A biography, which is widely considered by foremost Arabicists to have been composed by a disciple and later redacted, covers his first thirty years, and the rest are documented by his disciple al-Juzjani, who was also his secretary and his friend.

He was born in Persia around 980 (370 AH) in Afshana,

his mother's home, a small city now part of Uzbekistan. His father, a

respected Ismaili scholar, was from Balkh of the Persian province of Khorasan![]() , now part of Afghanistan, and was at the time of

his son's birth the governor of a village in one of the Samanid Nuh ibn

Mansur's estates. He had his son very carefully educated at Bukhara. Ibn Sina's

independent thought was served by an extraordinary intelligence and memory,

which allowed him to overtake his teachers at the age of fourteen.

, now part of Afghanistan, and was at the time of

his son's birth the governor of a village in one of the Samanid Nuh ibn

Mansur's estates. He had his son very carefully educated at Bukhara. Ibn Sina's

independent thought was served by an extraordinary intelligence and memory,

which allowed him to overtake his teachers at the age of fourteen.

Ibn Sina was put under the charge of a tutor, and his precocity soon made him the marvel of his neighbours; he displayed exceptional intellectual behaviour and was a child prodigy who had memorized the Quran by the age of 7 and a great deal of Persian poetry as well. From a greengrocer he learned arithmetic, and he began to learn more from a wandering scholar who gained a livelihood by curing the sick and teaching the young.

However he was greatly troubled by metaphysical

problems and in particular the works of Aristotle![]() . So, for the next year and a half, he also studied

philosophy, in which he encountered greater obstacles. In such moments of

baffled inquiry, he would leave his books, perform the requisite ablutions,

then go to the mosque, and continue in prayer till light broke on his

difficulties. Deep into the night he would continue his studies, and even in

his dreams problems would pursue him and work out their solution. Forty times,

it is said, he read through the Metaphysics of Aristotle, till the words were

imprinted on his memory; but their meaning was hopelessly obscure, until one

day they found illumination, from the little commentary by Farabi, which he

bought at a bookstall for the small sum of three dirhams. So great was his joy

at the discovery, thus made by help of a work from which he had expected only

mystery, that he hastened to return thanks to God, and bestowed alms upon the

poor.

. So, for the next year and a half, he also studied

philosophy, in which he encountered greater obstacles. In such moments of

baffled inquiry, he would leave his books, perform the requisite ablutions,

then go to the mosque, and continue in prayer till light broke on his

difficulties. Deep into the night he would continue his studies, and even in

his dreams problems would pursue him and work out their solution. Forty times,

it is said, he read through the Metaphysics of Aristotle, till the words were

imprinted on his memory; but their meaning was hopelessly obscure, until one

day they found illumination, from the little commentary by Farabi, which he

bought at a bookstall for the small sum of three dirhams. So great was his joy

at the discovery, thus made by help of a work from which he had expected only

mystery, that he hastened to return thanks to God, and bestowed alms upon the

poor.

He turned to medicine at 16, and not only learned medical theory, but also by gratuitous attendance on the sick had, according to his own account, discovered new methods of treatment. The teenager achieved full status as a physician at age 18 and found that "Medicine is no hard and thorny science, like mathematics and metaphysics, so I soon made great progress; I became an excellent doctor and began to treat patients, using approved remedies." The youthful physician's fame spread quickly, and he treated many patients without asking for payment.

Adulthood

His first appointment was that of physician to the emir, who owed him his recovery from a dangerous illness (997). Ibn Sina's chief reward for this service was access to the royal library of the Samanids, well-known patrons of scholarship and scholars. When the library was destroyed by fire not long after, the enemies of Ibn Sina accused him of burning it, in order for ever to conceal the sources of his knowledge. Meanwhile, he assisted his father in his financial labours, but still found time to write some of his earliest works.

When Ibn Sina was 22 years old, he lost his father. The Samanid dynasty came to its end in December 1004. Ibn Sina seems to have declined the offers of Mahmud of Ghazni, and proceeded westwards to Urgench in the modern Uzbekistan, where the vizier, regarded as a friend of scholars, gave him a small monthly stipend. The pay was small, however, so Ibn Sina wandered from place to place through the districts of Nishapur and Merv to the borders of Khorasan, seeking an opening for his talents. Shams al-Ma'äli Kavuus, the generous ruler of Dailam and central Persia, himself a poet and a scholar, with whom Ibn Sina had expected to find an asylum, was about that date (1002) starved to death by his troops who had revolted. Ibn Sina himself was at this season stricken down by a severe illness. Finally, at Gorgan, near the Caspian Sea, Ibn Sina met with a friend, who bought a dwelling near his own house in which Ibn Sina lectured on logic and astronomy. Several of Ibn Sina's treatises were written for this patron; and the commencement of his Canon of Medicine also dates from his stay in Hyrcania.

Ibn Sina subsequently settled at Rai, in the

vicinity of modern Tehran (present day capital of Iran), the home town of

Rhazes![]() ; where Majd Addaula, a son of the last Buwayhid

emir, was nominal ruler under the regency of his mother (Seyyedeh Khatun).

About thirty of Ibn Sina's shorter works are said to have been composed in

Rai. Constant feuds which raged between the regent and her second son, Amir

Shamsud-Dawala, however, compelled the scholar to quit the place. After a

brief sojourn at Qazvin he passed southwards to Hamadan, where another

Deylamite emir had established himself. At first, Ibn Sina entered into the

service of a high-born lady; but the emir, hearing of his arrival, called him

in as medical attendant, and sent him back with presents to his dwelling. Ibn

Sina was even raised to the office of vizier. The emir consented that he

should be banished from the country. Ibn Sina, however, remained hidden for

forty days in a sheikh's house, till a fresh attack of illness induced the

emir to restore him to his post. Even during this perturbed time, Ibn Sina

persevered with his studies and teaching. Every evening, extracts from his

great works, the Canon and the Sanatio, were dictated and explained to his

pupils. On the death of the emir, Ibn Sina ceased to be vizier and hid himself

in the house of an apothecary, where, with intense assiduity, he continued the

composition of his works.

; where Majd Addaula, a son of the last Buwayhid

emir, was nominal ruler under the regency of his mother (Seyyedeh Khatun).

About thirty of Ibn Sina's shorter works are said to have been composed in

Rai. Constant feuds which raged between the regent and her second son, Amir

Shamsud-Dawala, however, compelled the scholar to quit the place. After a

brief sojourn at Qazvin he passed southwards to Hamadan, where another

Deylamite emir had established himself. At first, Ibn Sina entered into the

service of a high-born lady; but the emir, hearing of his arrival, called him

in as medical attendant, and sent him back with presents to his dwelling. Ibn

Sina was even raised to the office of vizier. The emir consented that he

should be banished from the country. Ibn Sina, however, remained hidden for

forty days in a sheikh's house, till a fresh attack of illness induced the

emir to restore him to his post. Even during this perturbed time, Ibn Sina

persevered with his studies and teaching. Every evening, extracts from his

great works, the Canon and the Sanatio, were dictated and explained to his

pupils. On the death of the emir, Ibn Sina ceased to be vizier and hid himself

in the house of an apothecary, where, with intense assiduity, he continued the

composition of his works.

Meanwhile, he had written to Abu Ya'far, the prefect of the dynamic city of Isfahan, offering his services. The new emir of Hamadan, hearing of this correspondence and discovering where Ibn Sina was hidden, incarcerated him in a fortress. War meanwhile continued between the rulers of Isfahan and Hamadan; in 1024 the former captured Hamadan and its towns, expelling the Tajik mercenaries. When the storm had passed, Ibn Sina returned with the emir to Hamadan, and carried on his literary labours. Later, however, accompanied by his brother, a favourite pupil, and two slaves, Ibn Sina escaped out of the city in the dress of a Sufi ascetic. After a perilous journey, they reached Isfahan, receiving an honourable welcome from the prince.

Later life

The remaining ten or twelve years of Ibn Sina's life were spent in the service of Abu Ja'far 'Ala Addaula, whom he accompanied as physician and general literary and scientific adviser, even in his numerous campaigns.

During these years he began to study literary

matters and philology, instigated, it is asserted, by criticisms on his style.

He contrasts with the nobler and more intellectual character of Averroes![]() . A severe colic, which seized him on the march of

the army against Hamadan, was checked by remedies so violent that Ibn Sina

could scarcely stand. On a similar occasion the disease returned; with

difficulty he reached Hamadan, where, finding the disease gaining ground, he

refused to keep up the regimen imposed, and resigned himself to his fate.

. A severe colic, which seized him on the march of

the army against Hamadan, was checked by remedies so violent that Ibn Sina

could scarcely stand. On a similar occasion the disease returned; with

difficulty he reached Hamadan, where, finding the disease gaining ground, he

refused to keep up the regimen imposed, and resigned himself to his fate.

His friends advised him to slow down and take life moderately. He refused, however, stating that: "I prefer a short life with width to a narrow one with length". On his deathbed remorse seized him; he bestowed his goods on the poor, restored unjust gains, freed his slaves, and every third day till his death listened to the reading of the Qur'an. He died in June 1037, in his fifty-eighth year, and was buried in Hamadan, Iran.

Avicenna's tomb in Hamadan

Works

Scarcely any member of the Muslim circle of the sciences, including theology, philology, mathematics, astronomy, physics, and music, was left untouched by the treatises of Ibn Sina. This vast quantity of works - be they full-blown treatises or opuscula - vary so much in style and content (if one were to compare between the 'ahd made with his disciple Bahmanyar to uphold philosophical integrity with the Provenance and Direction, for example) that Yahya (formerly Jean) Michot has accused him of "neurological bipolarity".

Ibn Sina wrote at least one treatise on alchemy, but

several others have been falsely attributed to him. His book on animals was

translated by Michael Scot![]() . His Logic, Metaphysics, Physics, and De Caelo, are

treatises giving a synoptic view of Aristotelian doctrine, though the

Metaphysics demonstrates a significant departure from the brand of

Neoplatonism known as Aristotelianism in Ibn Sina's world; Arabic philosophers

have hinted at the idea that Ibn Sina was attempting to "re-Aristotelianise"

Muslim philosophy in its entirety, unlike his predecessors, who accepted the

conflation of Platonic, Aristotelian, Neo- and Middle-Platonic works

transmitted into the Muslim world.

. His Logic, Metaphysics, Physics, and De Caelo, are

treatises giving a synoptic view of Aristotelian doctrine, though the

Metaphysics demonstrates a significant departure from the brand of

Neoplatonism known as Aristotelianism in Ibn Sina's world; Arabic philosophers

have hinted at the idea that Ibn Sina was attempting to "re-Aristotelianise"

Muslim philosophy in its entirety, unlike his predecessors, who accepted the

conflation of Platonic, Aristotelian, Neo- and Middle-Platonic works

transmitted into the Muslim world.

The Logic and Metaphysics have been printed more than once, the latter, e.g., at Venice in 1493, 1495, and 1546. Some of his shorter essays on medicine, logic, etc., take a poetical form (the poem on logic was published by Schmoelders in 1836). Two encyclopedic treatises, dealing with philosophy, are often mentioned. The larger, Al-Shifa' (Sanatio), exists nearly complete in manuscript in the Bodleian Library and elsewhere; part of it on the De Anima appeared at Pavia (1490) as the Liber Sextus Naturalium, and the long account of Ibn Sina's philosophy given by Muhammad al-Shahrastani seems to be mainly an analysis, and in many places a reproduction, of the Al-Shifa'. A shorter form of the work is known as the An-najat (Liberatio). The Latin editions of part of these works have been modified by the corrections which the monastic editors confess that they applied. There is also a hikmat-al-mashriqqiyya, in Latin Philosophia Orientalis, mentioned by Roger Bacon, the majority of which is lost in antiquity, which according to Averroes was pantheistic in tone.

About 100 treatises were ascribed to Ibn Sina. Some of them are tracts of a few pages, others are works extending through several volumes. The best-known amongst them, and that to which Ibn Sina owed his European reputation, is his 14-volume The Canon of Medicine, which was a standard medical text in Europe and the Islamic world up until the 18th century. The book is known for its introduction of systematic experimentation and quantification into the study of physiology, the discovery of contagious diseases, the introduction of quarantine to limit the spread of infectious diseases, the introduction of clinical trials, and the first descriptions on bacteria and viral organisms.[It classifies and describes diseases, and outlines their assumed causes. Hygiene, simple and complex medicines, and functions of parts of the body are also covered. In this, Ibn Sina is credited as being the first to correctly document the anatomy of the human eye, along with descriptions of eye afflictions such as cataracts. It asserts that tuberculosis was contagious, which was later disputed by Europeans, but turned out to be true. It also describes the symptoms and complications of diabetes. Both forms of facial paralysis were described in-depth. In addition, the workings of the heart as a valve are described.

An Arabic edition of the Canon appeared at Rome in

1593, and a Hebrew version at Naples in 1491. Of the Latin version there were

about thirty editions, founded on the original translation by Gerard of

Cremona![]() . In the 15th century a commentary on the text of the Canon was

composed. Other medical works translated into Latin are the Medicamenta

Cordialia, Canticum de Medicina, and the Tractatus de Syrupo

Acetoso.

. In the 15th century a commentary on the text of the Canon was

composed. Other medical works translated into Latin are the Medicamenta

Cordialia, Canticum de Medicina, and the Tractatus de Syrupo

Acetoso.

It was mainly accident which determined that from

the 12th to the 18th century, Ibn Sina should be the guide of medical study in

European universities, and eclipse the names of Rhazes, Ali ibn al-Abbas and

Averroes. His work is not essentially different from that of his predecessor

Rhazes, because he presented the doctrine of Galen![]() , and through Galen the doctrine of Hippocrates

, and through Galen the doctrine of Hippocrates![]() , modified by the system of Aristotle, as well as

the Indian doctrines of Sushruta and Charaka. But the Canon of Ibn Sina is

distinguished from the Al-Hawi (Continens) or Summary of Rhazes by its

greater method, due perhaps to the logical studies of the former.

, modified by the system of Aristotle, as well as

the Indian doctrines of Sushruta and Charaka. But the Canon of Ibn Sina is

distinguished from the Al-Hawi (Continens) or Summary of Rhazes by its

greater method, due perhaps to the logical studies of the former.

The work has been variously appreciated in subsequent ages, some regarding it as a treasury of wisdom, and others, like Averroes, holding it useful only as waste paper. In modern times it has been seen of mainly historic interest as most of its tenets have been disproved or expanded upon by scientific medicine. The vice of the book is excessive classification of bodily faculties, and over-subtlety in the discrimination of diseases. It includes five books; of which the first and second discuss physiology, pathology and hygiene, the third and fourth deal with the methods of treating disease, and the fifth describes the composition and preparation of remedies. This last part contains some personal observations.

He is, like all his countrymen, ample in the enumeration of symptoms, and is said to be inferior to Ali in practical medicine and surgery. He introduced into medical theory the four causes of the Peripatetic system. Of natural history and botany he pretended to no special knowledge. Up to the year 1650, or thereabouts, the Canon was still used as a textbook in the universities of Leuven and Montpellier.

In the museum at Bukhara, there are displays showing many of his writings, surgical instruments from the period and paintings of patients undergoing treatment. Ibn Sina was interested in the effect of the mind on the body, and wrote a great deal on psychology, likely influencing Ibn Tufayl and Ibn Bajjah. He also introduced medical herbs.

Alchemy

As a chemist, Avicenna was the first to write refutations on alchemy. Four of these works were translated into Latin as:

Liber Aboali Abincine de Anima in arte Alchemiae

Declaratio Lapis physici Avicennae filio sui Aboali

Avicennae de congelatione et conglutinatione lapifum

Avicennae ad Hasan Regem epistola de Re recta

In one of these works, Ibn Sina was the first to discredit the theory of the transmutation of substances commonly believed by alchemists:

"Those of the chemical craft know well that no change can be effected in the different species of substances, though they can produce the appearance of such change."

Among his works refuting alchemy, Liber Aboali Abincine de Anima in arte Alchemiae was the most influential, having influenced later medieval chemists and alchemists such as Vincent of Beauvais.

Aromatherapy

Ibn Sina used steam distillation to produce the first essential oils. As a result, he is regarded as a pioneer of aromatherapy.

Astronomy

In 1070, Abu Ubayd al-Juzjani, a pupil of Ibn Sina, claimed that his teacher Ibn Sina had solved the equant problem in Ptolemy's planetary model.

Chemistry

In chemistry, steam distillation was invented by Ibn Sina in the early 11th century, which he used to produce essential oils.

Earth sciences

Ibn Sina wrote on the earth sciences in The Book of Healing. In geology, he hypothesized two causes of mountains:

"Either they are the effects of upheavals of the crust of the earth, such as might occur during a violent earthquake, or they are the effect of water, which, cutting itself a new route, has denuded the valleys, the strata being of different kinds, some soft, some hard... It would require a long period of time for all such changes to be accomplished, during which the mountains themselves might be somewhat diminished in size."

Physics

In physics, Ibn Sina was the first to employ an air thermometer to measure air temperature in his scientific experiments.

In mechanics, Ibn Sina developed an elaborate theory of motion, in which he made a distinction between the inclination and force of a projectile, and concluded that motion was a result of an inclination (mayl) transferred to the projectile by the thrower, and that projectile motion in a vacuum would not cease. He viewed inclination as a permanent force whose effect is dissipated by external forces such as air resistance. His theory of motion was thus consistent with the concept of inertia in Newton's first law of motion. Ibn Sina also referred to mayl to as being proportional to weight times velocity, a precursor to the concept of momentum in Newton's second law of motion. Ibn Sina's theory of mayl was further developed by Jean Buridan in his theory of impetus.

In optics, Ibn Sina discovered that the speed of light is finite, as he "observed that if the perception of light is due to the emission of some sort of particles by a luminous source, the speed of light must be finite." He also provided a sophisticated explanation for the rainbow phenomenon. Carl Benjamin Boyer described Ibn Sina's theory on the rainbow as follows:

"Independent observation had demonstrated to him that the bow is not formed in the dark cloud but rather in the very thin mist lying between the cloud and the sun or observer. The cloud, he thought, serves simply as the background of this thin substance, much as a quicksilver lining is placed upon the rear surface of the glass in a mirror. Ibn Sina would change the place not only of the bow, but also of the color formation, holding the iridescence to be merely a subjective sensation in the eye."

Philosophy

Ibn Sina wrote extensively on the subjects of philosophy, logic, ethics, metaphysics and other disciplines. Most of his works were written in Arabic - which was the de facto scientific language of that time, and some were written in the Persian language. Of linguistic significance even to this day are a few books that he wrote in nearly pure Persian language (particularly the Danishnamah-yi 'Ala', Philosophy for Ala' ad-Dawla'). Ibn Sina's commentaries on Aristotle often corrected the philosopher, encouraging a lively debate in the spirit of ijtihad.

Ibn Sina's philosophical tenets have become of great interest to critical Western scholarship and to those engaged in the field of Muslim philosophy, in both the West and the East. However, it is still the case that the West only pays attention to a portion of his philosophy known as the Latin Avicennian School. Ibn Sina's philosophical contributions have been overshadowed by Orientalist scholarship (for example that of Henri Corbin), which has sought to define him as a mystic rather than an Aristotelian philosopher. The so-called hikmat-al-mashriqqiyya remains a source of huge irritation to contemporary Arabic scholars, in particular Reisman, Gutas, Street, and Bertolacci.

The original work, entitled The Easterners (al-mashriqiyun), was probably lost during Ibn Sina's lifetime; Ibn Tufayl appended it to a romantic philosophical work of his own in the twelfth century, the Hayy ibn Yaqzan, in order to validate his philosophical system, and, by the time that the work was transmitted into the West, appended as it was to a set of "mystical" opusculae and sundry essays, it was firmly accepted as a demonstration of Ibn Sina's "esoteric" orientation, which he concealed out of necessity from his peers.

Some argue that such interpretations of Ibn Sina's "true" state of mind ignore the vast corpus of work that he produced, from major treatises to slurs on his enemies and rivals, misrepresent him utterly. It also detracts attention from the fact that Muslim philosophy flourished during the ten centuries after Ibn Sina's death, emerging from Ibn Sina's inflammatory pronouncements on all matters within the world, whether physical or metaphysical; the works of the post-Avicennian Baghdadi Peripatetics and anti-Peripatetics, for example, remain to be studied in much greater detail.

Metaphysical doctrine

Islamic philosophy, imbued as it is with theology, distinguishes more clearly than Aristotelianism the difference between essence and existence. Whereas existence is the domain of the contingent and the accidental, essence endures within a being beyond the accidental. However, Ibn Sina's commentaries upon the Metaphysics in particular demonstrate that he was much more clearly aligned with a philosophical comprehension of the metaphysical world rather than one that was grounded in theology. (See, for example, the Compendium on the Soul, where beneath the heading of Metaphysics he prioritises Universal Science (Being-as-such and First Philosophy) over theology.) The philosophy of Ibn Sina, particularly that part relating to metaphysics, owes much to Aristotle and to Al-Farabi. The search for a truly definitive Islamic philosophy can be seen in what is left to us of his work.

God as the first cause of all things

For Ibn Sina, essence is non-contingent. For an essence to be realised within time (as an existence), the existence must be rendered necessary by the essence itself. This particular relationship of cause and effect is due to an inherent property of the essence, that it is non-contingent. For existence in general to be possible, there must exist a necessary essence, itself uncaused - a being or God to begin a process of emanation.

This view has a profound impact on the monotheistic concept of creation. Existence is not seen by Ibn Sina as the work of a capricious deity, but of a divine, self-causing thought process. The movement from this to existence is necessary, and not an act of will per se. The world emanates from God by virtue of his abundant intellect - an immaterial cause as found in the neoplatonic concept of emanation.

Ibn Sina found inspiration for this metaphysical view in the works of Al-Farabi, but his innovation is in his account a single and necessary first cause of all existence. Whether this view can be reconciled with Islam, particularly given the question of what role is left for God's will, was to become a subject of considerable controversy within intellectual Islamic discourse.

The Ten Intellects

In Ibn Sina's account of creation (largely derived from Al-Farabi), from this first cause (or First Intellect) proceeds the creation of the material world.

The First Intellect, in contemplating the necessity of its existence, gives rise to the Second Intellect. In contemplating its emanation from God, it then gives rise to the First Spirit, which animates the Sphere of Spheres (the universe). In contemplating itself as a self-caused essence (that is, as something that could potentially exist), it gives rise to the matter that fills the universe and forms the Sphere of the Planets (the First Heaven in al-Farabi).

This triple-contemplation establishes the first stages of existence. It continues, giving rise to consequential intellects which create between them two celestial hierarchies: the Superior Hierarchy of Cherubim (Kerubim) and the Inferior Hierarchy, called by Ibn Sina "Angels of Magnificence". These angels animate the heavens, but are deprived of all sensory perception, but have imagination which allows them to desire the intellect from which they came. Their vain quest to join this intellect causes an eternal movement in heaven. They also cause prophetic visions in humans.

The angels created by each of the next seven Intellects are associated with a different body in the Sphere of the Planets. These are: Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, the Sun, Venus, Mercury and the Moon. The last of these is of particular importance, since its association is with the Angel Gabriel ("The Angel").

This Ninth Intellect occurs at a step so removed from the First Intellect that the emanation that then arises from it explodes into fragments, creating not a further celestial entity, but instead creating human souls, which have the sensory functions lacked by the Angels of Magnificence.

The Angel and the minds of humans

For Ibn Sina, human minds were not in themselves formed for abstract thought. Humans are intellectual only potentially, and only illumination by the Angel confers upon them the ability to make from this potential a real ability to think. This is the Tenth Intellect, identified with the "active intellect" of Aristotle's De Anima.

The degree to which minds are illuminated by the Angel varies. Prophets are illuminated to the point that they posses not only rational intellect, but also an imagination and ability which allows them to pass on their superior wisdom to others. Some receive less, but enough to write, teach, pass laws, and contribute to the distribution of knowledge. Others receive enough for their own personal realisation, and others still receive less.

On this view, all humanity shares a single agent intellect - a collective consciousness. The final stage of human life, according to Ibn Sina, is reunion with the emanation of the Angel. Thus, the Angel confers upon those imbued with its intellect the certainty of life after death. For Ibn Sina, as for the neoplatonists who influenced him, the immortality of the soul is a consequence of its nature, and not a purpose for it to fulfill.

Criticism

Ibn Sina's heterodox beliefs, namely his belief that bodily resurrection was impossible, placed him at odds with traditionalist Muslim scholars of his time. This departure from orthodox thought led the prominent Ash'ari scholar al-Ghazzali to consider Ibn Sina a disbeliever of Islam, and he argued that it was hard to consider him a Kafir.

Logic

The first criticisms on Aristotelian logic were written by Ibn Sina, who produced independent treatises on logic rather than commentaries. He criticized the logical school of Baghdad for their devotion to Aristotle at the time. He investigated the theory of definition and classification and the quantification of the predicates of categorical propositions, and developed an original theory on "temporally modalized" syllogism. Its premises included modifiers such as "at all times", "at most times", and "at some time".

Natural philosophy

Ibn Sina and Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, who are both regarded as two of the greatest polymaths in Persian history, engaged in a written debate, with al-Biruni mostly criticizing Aristotelian natural philosophy and the Peripatetic school, while Avicenna and his student Ahmad ibn 'Ali al-Ma'sumi respond to al-Biruni's criticisms in writing. Al-Biruni began by asking Avicenna eighteen questions, ten of which were criticisms of Aristotle's On the Heavens. After Avicenna responded to the questions, al-Biruni was unsatisfied with some of the answers and wrote back commenting on them, after which Avicenna's student Ahmad ibn 'Ali al-Ma'sumi wrote back on behalf of Avicenna.

Engineering

In the chapters on mechanics and engineering in his encyclopedia Mi'yar al-'aql (The Measure of the Mind), Avicenna writes an analysis on the ilm al-hiyal (science of ingenious devices) and makes the first successful attempt to classify simple machines and their combinations. He first describes and illustrates the five constituent simple machines: the lever, pulley, screw, wedge, and windlass. He then analyzes all the combinations of these simple machines, such as the windlass-screw, windlass-pulley and windlass-lever for example. He is also the first to describe a mechanism which is essentially a combination of all of these simple machines (except for the wedge).

Poetry

Almost half of Ibn Sina's works are versified. His poems appear in both Arabic and Persian. As an example, Edward Granville Browne claims that the following verses are incorrectly attributed to Omar Khayyám, and were originally written by Ibn Sina :

Up from Earth's Centre through the Seventh Gate

I rose, and on the Throne of Saturn sate,

And many Knots unravel'd by the Road;

But not the Master-Knot of Human Fate.

Legacy

George Sarton, the father of the history of science,

described Ibn Sina as "one of the greatest thinkers and medical scholars

in history" and called him "the most famous scientist of Islam and

one of the most famous of all races, places, and times." He was one of

the Islamic world's leading writers in the field of medicine. He was

influenced by the approach of Hippocrates and Galen, as well as Sushruta and

Charaka. Along with Rhazes, Abulcasis/Albucasis![]() , Ibn al-Nafis, and al-Ibadi, Ibn Sina is considered

an important compiler of early Muslim medicine. He is remembered in Western

history of medicine as a major historical figure who made important

contributions to medicine and the European Renaissance. Ibn Sina is also

considered the father of the fundamental concept of momentum in physics.

, Ibn al-Nafis, and al-Ibadi, Ibn Sina is considered

an important compiler of early Muslim medicine. He is remembered in Western

history of medicine as a major historical figure who made important

contributions to medicine and the European Renaissance. Ibn Sina is also

considered the father of the fundamental concept of momentum in physics.

In Iran, he is considered a national icon, and is often regarded as one of the greatest Persians to have ever lived. Many portraits and statues remain in Iran today. An impressive monument to the life and works of the man who is known as the 'doctor of doctors' still stands outside the Bukhara museum and his portrait hangs in the Hall of the Faculty of Medicine in the University of Paris. There is also a crater on the moon named Avicenna.

Ibn Sina commemorated on a Polish stamp

Imaginary

portrait of Ibn Sina as seen depicted on a stamp

issued by the United Arab Emirates

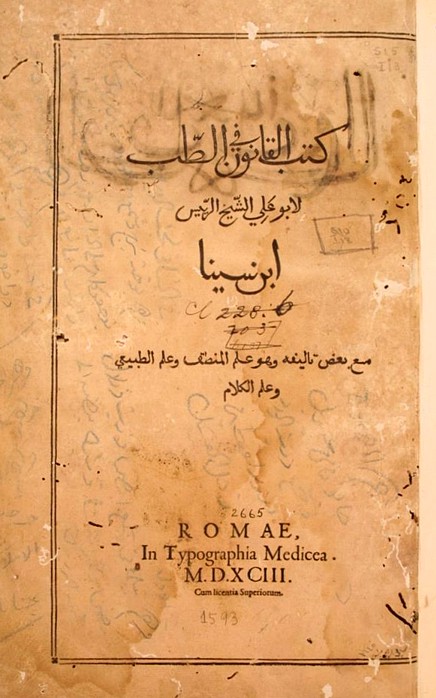

A copy of the Canon of Medicine dated 1593

The Canon of Medicine (original title in Arabic "Al-qanun fi al-tibb") is a 14-volume medical encyclopedia by the Persian Muslim scientist and physician Abu Ali ibn Sina (Avicenna), circa 1020. The book was based on a combination of his own personal experience, medieval Islamic medicine, the writings of Galen, Sushruta, and Charaka, and ancient Persian and Arabian medicine. The Canon is considered one of the most famous books in the history of medicine.

Also known as the Qanun, which means "law" in Arabic and Persian, the Canon of Medicine remained a medical authority up until the 18th century. It set the standards for medicine in Europe and the Islamic world, and is Avicenna's most well-renowned written work. The principles of medicine described by him ten centuries ago in this book, are still taught at UCLA and Yale University, among others, as part of the history of medicine. Among other things, the book is known for the introduction of systematic experimentation and quantification into the study of physiology, the discovery of the contagious nature of infectious diseases, the introduction of quarantine to limit the spread of contagious diseases, the introduction of clinical trials, and the first descriptions on bacteria and viral organisms.

George Sarton, the father of the history of science, wrote in the Introduction to the History of Science: "One of the most famous exponents of Muslim universalism and an eminent figure in Islamic learning was Ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna (981-1037). For a thousand years he has retained his original renown as one of the greatest thinkers and medical scholars in history. His most important medical works are the Qanun (Canon) and a treatise on Cardiac drugs. The 'Qanun fi-l-Tibb' is an immense encyclopedia of medicine. It contains some of the most illuminating thoughts pertaining to distinction of mediastinitis from pleurisy; contagious nature of phthisis; distribution of diseases by water and soil; careful description of skin troubles; of sexual diseases and perversions; of nervous ailments."

Overview

The book explains the causes of health and disease. Ibn Sina believed that the human body cannot be restored to health unless the causes of both health and disease are determined. Ibn Sina stated that medicine (tibb) is the science by which we learn the various states of the human body when in health and when not in health, and the means by which health is likely to be lost, and when lost, is likely to be restored. In other words, medicine is the science whereby health is conserved and the art whereby it is restored after being lost.

Avicenna regarded the causes of good health and diseases to be:

The Material causes.

The Elements.

The Humors.

The Variability of the Humors.

The Temperaments.

The Psychic Faculties.

The Vital Force.

The Organs.

The Efficient Causes.

The Formal Causes.

The Vital Faculties.

The Final Causes.

There are many other sources that explain his concepts in depth and are accessible through the world-wide web in medical and Islamic sites.

The Qanun distinguishes mediastinitis from pleurisy and recognises the contagious nature of phthisis (tuberculosis of the lung) and the spread of disease by water and soil. It gives a scientific diagnosis of ankylostomiasis and attributes the condition to an intestinal worm. The Qanun points out the importance of dietetics, the influence of climate and environment on health and the surgical use of oral anesthetics. Ibn Sina advised surgeons to treat cancer in its earliest stages, ensuring the removal of all the diseased tissue. The Qanun 's materia medica considers some 760 drugs, with comments on their application and effectiveness. He recommended the testing of a new drug on animals and humans prior to general use.

Ibn Sina noted the close relationship between emotions and the physical condition and felt that music had a definite physical and psychological effect on patients. Of the many psychological disorders that he described in the Qanun, one is of unusual interest: love sickness! Ibn Sina is reputed to have diagnosed this condition in a Prince in Jurjan who lay sick and whose malady had baffled local doctors. Ibn Sina noted a fluttering in the Prince's pulse when the address and name of his beloved were mentioned. The great doctor had a simple remedy: unite the sufferer with the beloved.

The earliest known copy of the Canon of Medicine dated 1052 is held in the collection of the Aga Khan and is to be housed in the Aga Khan Museum planned for Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Avicenna's Canon of Medicine in Europe

The Arabic text of the Qanun was translated into

Latin as Canon medicinae by Gerard of Cremona![]() in the 12th century and into Hebrew in 1279.

Henceforth the Canon served as the chief guide to medical science in the West

and is said to have influenced Leonardo da Vinci. Its encyclopedic content,

its systematic arrangement and philosophical plan soon worked its way into a

position of pre-eminence in the medical literature of Europe, displacing the

works of Galen and becoming the text book for medical education in the schools

of Europe. The text was read in the medical schools at Montpellier and Leuven

as late as 1650, and Arnold C. Klebs described it as "one of the most

significant intellectual phenomena of all times." In the words of Dr.

William Osler, the Qanun has remained "a medical bible for a longer time

than any other work". The first three books of the Latin Canon were

printed in 1472, and a complete edition appeared in 1473. The 1491 Hebrew

edition is the first appearance of a medical treatise in Hebrew and the only

one produced during the 15th century. In the last 30 years of the 15th century

it passed through 15 Latin editions. In recent years, a partial translation

into English was made.

in the 12th century and into Hebrew in 1279.

Henceforth the Canon served as the chief guide to medical science in the West

and is said to have influenced Leonardo da Vinci. Its encyclopedic content,

its systematic arrangement and philosophical plan soon worked its way into a

position of pre-eminence in the medical literature of Europe, displacing the

works of Galen and becoming the text book for medical education in the schools

of Europe. The text was read in the medical schools at Montpellier and Leuven

as late as 1650, and Arnold C. Klebs described it as "one of the most

significant intellectual phenomena of all times." In the words of Dr.

William Osler, the Qanun has remained "a medical bible for a longer time

than any other work". The first three books of the Latin Canon were

printed in 1472, and a complete edition appeared in 1473. The 1491 Hebrew

edition is the first appearance of a medical treatise in Hebrew and the only

one produced during the 15th century. In the last 30 years of the 15th century

it passed through 15 Latin editions. In recent years, a partial translation

into English was made.

Avicenna

Persian physician and philosopher, born at Kharmaithen (?) <Afshana>, in the province of Bokhara, 980; died at Hamadan, in Northern Persia, 1037. From the autobiographical sketch which has come down to us we learn that he was a very precocious youth; at the age of ten he knew the Koran by heart; before he was sixteen he had mastered what was to be learned of physics, mathematics, logic, and metaphysics; at the age of sixteen he began the study and practice of medicine; and before he had completed his twenty-first year he wrote his famous "Canon" of medical science, which for several centuries, after his time, remained the principal authority in medical schools both in Europe and in Asia.

He served successively several Persian potentates as physician and adviser, travelling with them from place to place, and despite the habits of conviviality for which he was well known, devoted much time to literary lobours, as is testified by the hundred volumes which he wrote. Our authority for the foregoing facts is the "Life of Avicenna,", based on his autobiography, written by his disciple Jorjani (Sorsanus), and published in the early Latin editions of his works. Besides the medical "Canon," he wrote voluminous commentaries on Arisotle's works and two great encyclopedias entitled "Al Schefa", or "Al Chifa" (i.e. healing) and "Al Nadja" (i.e. deliverance).

The "Canon" and portions of the encyclopedias were translated into Latin as early as the twelfth century, by Gerard of Cremona, Dominicus Gundissalinus, and John Avendeath; they were published at Venice, 1493-95. The complete Arabic texts are said to be are said to be in the manuscript. in the Bodleian Library. An Arabic text of the "Canon" and the "Nadja" was published in Rome, 1593.

Avicenna's philosophy, like that of his predecessors among the Arabians, is Aristoteleanism mingled with neo-Platonism, an exposition of Aristotle's teaching in the light of the Commentaries of Thomistius, Simplicius, and other neo-Platonists. His Logic is divided into nine parts, of which the first is an introduction after the manner of Porphyry's "Isagoge"; then follow the six parts corresponding to the six treatises composing the "Organon"; the eighth and ninth parts consist respectively of treatises on rhetoric and poetry. Avicenna devoted special attention to definition, the logic of representation, as he styles it, and also to the classification of sciences. Philosophy, he says, which is the general name for scientific knowledge, includes speculative and practical philosophy. Speculative philosophy is divided into the inferior science (physics), and middle science (mathematics), and the superior science (metaphysics including theology). Practical philosophy is divided into ethics (which considers man as an individual); economics (which considers man as a member of domestic society); and politics (which considers man as a member of civil society). These divisions are important on account of their influence on the arrangement of sciences in the schools where the philosophy of Avicenna preceded the introduction of Aristotle's works.

A favourite principle of Avicenna, which is quoted not only by Averroes but also by the Schoolmen, and especially by St. Albert the Great, was intellectus in formis agit universalitatem, that is, the universality of our ideas is the result of the activity of the mind itself. The principle, however, is to be understood in the realistic, not in the nominalistic sense. Avicenna's meaning is that, while there are differences and resemblances among things independently of the mind, the formal constitution of things in the category of individuality, generic universality, specific universality, and so forth, is the work of the mind.

Avicenna's physical doctrines show him in the light of a faithful follower of Aristotle, who has nothing of his own to add to the teaching of his master. Similarly, in psychology, he reproduces Aristotle's doctrines, borrowing occasionally an explanation, or an illustration, from Alfarabi. On one point, however, he is at pains to set the true meaning, as he understands it, of Aristotle, above all the exposition and elaboration of the Commentators. That point is the question of the Active and Passive Intellect. He teaches that the latter is the individual mind in the state of potency with regard to knowledge, and that the former is the impersonal mind in the state of actual and perennial thought. In order that the mind acquire ideas, the Passive Intellect must come into contact with the Active Intellect. Avicenna, however, insists most emphatically that a contact of that kind does not interfere with the independent substantiality of the Passive Intellect, and does not imply that it is merged with the Active Intellect.

He explicitly maintains that the individual mind retains its individuality and that, because it is spiritual and immaterial, it is endowed with personal immortality. At the same time, he is enough of a mystic to maintain that certain choice souls are capable of arriving at a very special kind of union with the Universal, Active, Intellect, and of attaining thereby the gift of prophecy. Metaphysics he defines as the science of supernatural (ultra-physical) being and of God. It is, as Aristotle says, the theological science. It treats of the existence of God, which is proved from the necessity of a First Cause; it treats of the Providence of God, which, as all the Arabians taught, is restricted to the universal laws of nature, the Divine Agency being too exalted to deal with singular and contingent events; it treats of the hierarchy of mediators between God and material things, all of which emanated from God, the Source of all sources, the Principle of all principles. The first emanation from God is the world of ideas. This is made up of pure forms, free from change, composition, or imperfection; it is akin to the Intelligible world of Plato, and is, in fact, a Platonic concept. Next to the world of ideas is the world of souls, made up of forms which are, indeed, intelligible, but not entirely separated from matter. It is these souls that animate and energize the heavenly spheres. Next to the world of souls is the world of physical forces, which are more or less completely embedded in terrestrial matter and obey its laws; they are, however, to some extent amenable to the power of intelligence in so far as they may be influenced by magic art. Lastly comes the world of corporeal matter; this, according to the neo-Platonic conception which dominates Avicenna's thought in this theory of emanation, is of itself wholly inert, not capable of acting but merely of being acted upon (Occasionalism).

In this hierarchical arrangement of beings, the Active Intellect, which, as was pointed out above, plays a necessary role in the genesis of human knowledge, belongs to the world of Ideas, and is of the same nature as the spirits which animate the heavenly spheres. From all this it is apparent that Avicenna is no exception to the general description of the Arabian Aristoteleans as neo-Platonic interpreters of Aristotle. There remain two other doctrines of general metaphysical nature which exhibit him in the character of an original, or rather an Arabian, and not a neo-Platonic interpreter. The first is his division of being into three classes: (a) what is merely possible, including all sublunary things; (b) what is itself merely possible but endowed by the First Cause with necessity; such are the ideas that rule the heavenly spheres; (c) what is of its own nature necessary, namely, the First Cause. This classification is mentioned and refuted by Averroes. The second doctrine, to which also Averroes alludes, is a fairly outspoken system of pantheism which Avicenna is said to have elaborated in a work, now lost, entitled "Philosophia Orientalis". The Scholastics, apparently, know nothing of the special work on pantheism; they were, however, aware of the pantheistic tendencies of Avicenna's other works on philosophy, and were, accordingly, reluctant to trust in his exposition of Aristotle.

William

Turner

Transcribed by

Geoffrey K. Mondello, Amy M. Mondello, and Stephen St. Damian Mondello

The Catholic Encyclopedia