Lessico

Georg

Bauer

Georgius Agricola

In tedesco Bauer significa contadino e venne latinizzato in Agricola. Medico e mineralogista tedesco (Glauchau, Sassonia, 1494 - Chemnitz 1555). È considerato il fondatore dell'ingegneria mineraria e della mineralogia. Stabilitosi come medico nella città mineraria di Joachimsthal e quindi a Chemnitz, esercitò la sua professione nelle miniere dei Fugger. Espose i risultati dei suoi studi e delle esperienze dirette in numerosi trattati e saggi, i più importanti dei quali sono: De ortu et causis subterraneorum (1544), in cui critica le teorie degli antichi sull'origine dei minerali; De natura fossilium (1546), trattato di mineralogia in 10 libri; De re metallica (1556), opera postuma in 12 libri, primo trattato organico sull'arte mineraria, che per secoli costituì il testo base in materia. Comprende un resoconto delle varie operazioni minerarie, includendo anche nozioni di geologia, preparazione dei minerali e metallurgia.

Georg Bauer

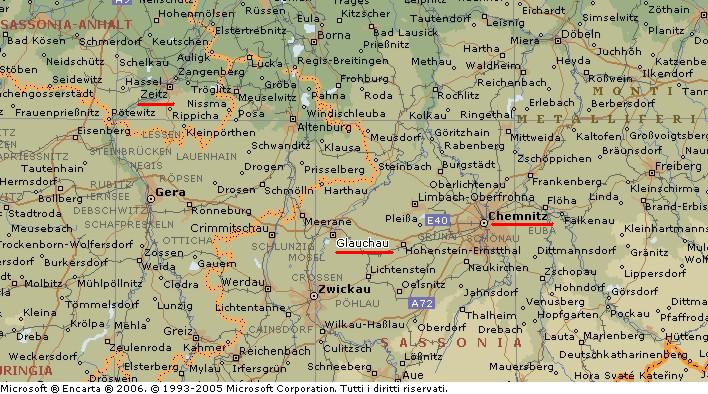

Georg Bauer – Giorgio l'Agricoltore – o Georgius Agricola (Glauchau, Sassonia, 24 marzo 1494 – Chemnitz, 21 novembre 1555) è stato uno scienziato e mineralogista tedesco. È conosciuto come il padre della mineralogia. Il suo vero nome era Georg Pawer (o Georg Bauer). Agricola è la versione latina del suo cognome, dato che Bauer in tedesco significa contadino.

Dotato di un precoce intelletto, fin da giovane ha teso tutto se stesso alla ricerca di nuovi metodi per apprendere, tanto che all'età di vent'anni è stato nominato rettore straordinario di greco alla cosiddetta Grande Scuola di Zwickau, in Germania, e iniziò anche la sua carriera di scrittore in filologia.

Dopo due anni si ritirò da questo incarico per proseguire i suoi studi a Lipsia, dove, come rettore, ricevette il supporto del professore di classici Peter Mosellanus (1493-1524), un celebrato umanista del tempo, con cui Agricola era già in corrispondenza. Qui votò sé stesso agli studi di medicina, fisica, e chimica. Dopo la morte di Mosellanus, egli fece un viaggio in Italia dal 1524 al 1526, dove conseguì il suo dottorato.

Agricola tornò a Zwickau nel 1527 e fu scelto come fisico e medico della città a Jáchymov (in tedesco Joachimsthal), un importante centro minerario e metallurgico boemo, dato che il suo obiettivo era in parte quello di "riempire il vuoto nell'arte curativa", e in parte di testare lo stato dell'arte della letteratura mineralogica attraverso meticolose osservazioni di giacimenti minerari e dei metodi di trattamento dei minerali.

La sua profonda conoscenza della filologia e della filosofia lo aveva abituato al pensiero sistematico, fornendogli la capacità di teorizzare i suoi studi e osservazioni sui minerali in un sistema logico, che cominciò a pubblicare nel 1528.

Il suo

dialogo Bermannus, sive de re metallica dialogus (1530), il primo

tentativo di portare la conoscenza dal puro piano teorico della scienza del

tempo a quello pratico del lavoro, portò Agricola alla ribalta, tanto che il

libro comincia con una lettera di apprezzamento di Erasmo da Rotterdam![]() .

Sempre nel 1530 il Principe Maurizio di Sassonia lo nominò storiografo,

dandogli un contratto annuale, e così Agricola emigrò a Chemnitz, il centro

dell'industria mineraria dell'epoca, in modo tale da poter ampliare il suo

raggio di osservazione. I cittadini mostrarono di apprezzare molto i suoi

studi, nominandolo fisico della città nel 1533. Nello stesso anno pubblicò

un libro sul sistema di pesi e misure di Greci e Romani, intitolato De

Mensuris et Ponderibus.

.

Sempre nel 1530 il Principe Maurizio di Sassonia lo nominò storiografo,

dandogli un contratto annuale, e così Agricola emigrò a Chemnitz, il centro

dell'industria mineraria dell'epoca, in modo tale da poter ampliare il suo

raggio di osservazione. I cittadini mostrarono di apprezzare molto i suoi

studi, nominandolo fisico della città nel 1533. Nello stesso anno pubblicò

un libro sul sistema di pesi e misure di Greci e Romani, intitolato De

Mensuris et Ponderibus.

Fu anche eletto borgomastro di Chemnitz. La sua popolarità, tuttavia, fu di breve durata. Chemnitz, infatti, fu un violento centro del movimento protestante, mentre Agricola non aveva mai abbandonato la fede nella vecchia religione cattolica. Così fu obbligato ad abbandonare il suo posto pubblico, rassegnando le dimissioni dalla carica di borgomastro. Si ritirò a vita privata, lontano dai movimentati contenziosi dell'epoca, votandosi interamente allo studio. Il suo interesse principale restava sempre la mineralogia, anche se continuava a occuparsi di medicina, matematica, teologia e storiografia. La sua principale opera storica fu il Dominatores Saxonici a prima origine ad hanc aetatem, pubblicato a Friburgo. Nel 1544 pubblicò il De ortu et causis subterraneorum, in cui poneva le basi della geologia fisica e della geologia applicata, criticando le vecchie teorie sull'argomento. Nel 1545 seguì il De natura eorum quae effluunt e terra, nel 1546 il De veteribus et novis metallis, un compendio sulla scoperta e occorrenza dei minerali, mentre nel 1548 pubblicò il De animantibus subterraneis, a cui seguirono negli anni seguenti svariate piccole pubblicazioni sui metalli.

Il suo lavoro più famoso, il De re metallica libri xii, fu pubblicato nel 1556, sebbene apparentemente sia stato terminato molti anni prima, vista che la dedica all'elettore e suo fratello è datata 1550. Questo libro è un completo e sistematico trattato sulla attività mineraria e sulla metallurgia ed è illustrato con raffinate e interessanti xilografie, inoltre contiene in appendice gli equivalenti in tedesco dei termini tecnici usati nel testo in latino. Questo libro è rimasto a lungo un'opera di riferimento e pone il suo autore tra i più esperti chimici del suo tempo.

Nonostante la prova di tolleranza che Agricola aveva nella questione religiosa, non finì la sua vita in pace. Rimase fino alla fine uno strenuo cattolico, sebbene tutti a Chemnitz fossero diventati luterani; e si dice che Agricola morì per un attacco di apoplessia dovuta a un'accesa discussione con un teologo protestante. Morì a Chemnitz il 21 novembre 1555, ed era così violento il risentimento teologico nei suoi confronti che non fu neanche sepolto nella città cui aveva dato lustro. Tra due ali di dimostranti fu portato a Zeitz, 60 km in linea d'aria a dordovest di Chemnitz, e lì fu sepolto.

Il De Re Metallica è considerato un documento classico dell'alba della metallurgia, rimasto insuperato per due secoli. Nel 1912 il Mining Magazine di Londra ne pubblicò una traduzione fatta dall'ingegnere minerario americano Herbert Hoover, oggi meglio ricordato nella sua veste di presidente degli Stati Uniti d'America, e da sua moglie Lou Henry Hoover.

Le opere più importanti

De re

metallica libri XII. Springer, Berlino 2004, ISBN 3-540-20870

Bermannus sive de re metallica. Belles Lettres, Parigi 1990, ISBN

2-25134504-3 (Nachdruck der Ausgabe Basel 1530)

De animantibus subterraneis liber. VDI-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1978, ISBN

3-18-400400-7 (Nachdruck der Ausgabe Basel 1549)

De natura eorum, quae effluunt ex terra. SNM, Bratislava 1996, ISBN

80-85753-91-X (Nachdruck der Ausgabe Basel 1546)

De natura fossilium libri X. Dover Publications, Mineola, N.Y. 2004,

ISBN 0-486-49591-4 (Nachdruck der Ausgabe Basel 1546)

1544: De ortu et causis subterraneorum libri V

1546: De veteribus et novis metallis libri II

1550: De mensuris quibus intervalla metimur liber

1550: De precio metallorum et monetis liber III

De re metallica, a treatise by Agricola (1490-1555) [sic!] on mining and smelting, is a seminal, lavishly illustrated book considered by many to be the foundation upon which the science of metallurgy has been built. First published (posthumously) in 1556, the book is remarkable as one of the earliest works of natural science to be based on careful observation, as opposed to speculation. Born Georg Bauer, the man later known as Agricola studied medicine and became physician and apothecary in a prominent mining district in central Europe.

His interest in occupational mining diseases led to frequent visits to mines and painstaking observation of mining practices. He first summarized his knowledge of mining and metallurgy in 1530 in Bermannus sive de re metallica dialogus. Near the end of his life he expanded this shorter work into De re metallica libri XII and worked closely with a talented illustrator for three years to devise a harmonious and useful marriage of pictures and words. The result was a series of 292 remarkably detailed and animated woodcuts by Blasius Weffring, showing cutaway views of equipment and procedures explained in the text. Weffring’s woodcuts served to illustrate seven editions of the book published between 1556 and 1657, two of which (1561 and 1621) are among the many rare books available in the Institute Archives and Special Collections, a department of the MIT Libraries.

http://libraries.mit.edu

Georgius

Agricola.

Adam

Melchior - Vitae Germanorum medicorum, 1620

|

Patriam nactus est Georgius

Agricola Glaucham, oppidum in Misenorum vel Hermundurorum regione,

argenti ac metallorum ferace; adeo ut Henrico duci Misniae solae

Friburgenses venae tantam argenti copiam largitae sint, quanta tum, ut

annales loquuntur, suffecisset empturo Boemiae regnum. Ibi

ergo Agricola primum huius caeli aerem hausit, anno ab exhibito Messia

millesimo quadringentesimo, nonagesimo quarto, die vicesima quarta

Martii, inter horam quartam et quintam vespertinam. Cum

fundamenta bonarum literarum in Germania feliciter posuisset: et anno

Christi decimo octavo Cygnaeae ludum Graecum aperuisset: ac post

Lipsiam profectus Petri Mosellani, qui eo tempore columna habebatur

Universitatis, Lector fuisset: abiit in Italiam, ubi inter alios

audivit Nicolaum Anconem, et Ioannem Naevium; quorum alter in

medicina, quam docent Arabas secuti, diligenter fuit versatus; alter

tum in Latinis et Graecis literis, tum maxime veteri illa medicina

eruditus. Ex Italia in patriam reverso, nihil fuit potius, quam ut se

ad Sudetos conferret montes, totius Europae fertilissimos argenti. Ad

quos ut venit: statim cepit ardere studio rei metallicae cognoscendae:

quod pleraque opinione multo maiora invenisset. Anno

post, cum viri amicissimi, quorum auctoritas multum apud ipsum valebat,

ei suasissent; in valle Ioachimica suscepit officium et munus medendi.

Tunc vero quicquid temporis ei vacuum fuit a curandis aegrotis, a

valetudine sustentanda, a cura rei domesticae: id totum consumpsit

partim in percunctandis hominibus, artis metallicae peritis, partim in

legendis scriptoribus Graecis et Latinis, quos aliquid de metallis

putabat memoriae prodidisse. Sed cum videret exstare perpauca, plura

abolita: ipse animum induxit scribere de rebus subterraneis; quae vel

legisset, vel ex peritis artis metallicae didicisset, vel ipse

vidisset in fodinis et officinis. Ex

valle Ioachimica Chemnitium Hermundurorum commigravit: ubi se studio

Physicae et medicinae totum dedidit: conatusque est subterranea e

tenebris, quibus obruta iacuerunt, eruere, et in lucem proferre. Quod

ut eo felicius praestaret, Mauricius Saxoniae dux dedit ei immunitatem

aedium, et vacationem publici muneris: ac Georgii Commerstadii

Iureconsulti suasu annuum eidem stipendium decrevit. Fecit ipse non

parvos de suo in eam rem sumptus, et rei familiaris iacturam non

exiguam. Dum enim toto animo in ea studia incubuit: abiecit curam

rerum privatarum: quas honestis rationibus multum potuisset augere: si

vel divitias, vel opes, vel honores maioris aestimasset; quam

cognitionem rerum occultarum, contemplationemque natura. Scripsit

ergo de ortu et causis subterraneorum. De

natura eorum, quae effluunt ex terra. De

natura fossilium. De

medicatis fontibus. De

subterraneis animantibus. De

veteribus et novis metallis. De

re metallica libros duodecim: ubi non solum omnia ad metallicam

spectantia luculente describuntur; sed et per effigies suis locis

insertas, additis Latinis Germanicisque nominibus, ita ob oculos

ponuntur; ut clarius tradi non possint. De

pretio metallorum et monetis. De

mensuris et ponderibus externis. De

restituendis ponderibus et mensuris. De

Romanorum et Graecorum mensuris et ponderibus. De

mensuris quibus intervalla metimur. De

animantibus subterraneis. Sunt

eius et de peste libri, et de traditionibus Apostolicis: sed an editi

in lucem sint, necne, dubitamus. Equidem

monumentis editis et praeclare ipse de re literaria est meritus; et

nomen suum immortalitati consecravit. Litem ei movit Andreas Alciatus,

super disquisitione de mensuris et ponderibus: cui Agricola brevi

defensione respondit. Amicis

praecipue usus est Wolffgango Meurero, metallica a puero docto, quae

Aldeburgum patria eius gignit: Georgio item Fabricio, antiquitatis

omnis studioso: Valerio Cordo, Romae immatura, sed beata morte

exstincto, Erasmo Roterodamo, cuius exstat ad ipsam epistola, Ioanne

Dryandro, Paulo Ebero, Cornelio Sittardo, Caspare Cornero, et aliis

viris doctis. In

bello Germanico, cum Mauricius et Augustus fratres, Caesaris exercitum

per Bohemiam sequerentur: Agricola, uxore praegnante cum dulcissimis

liberis domi relicta, fortunis etiam omnibus posthabitis, cum

iusiurandum, quo cis erat devinctus, nullo modo negligendum putaret,

in exercitu eorum paene senex militavit. De

obitu et doctrina eius hoc elogium [Note: lib. 16. hist. Thuani de

Agricola elogium.] reliquit Iacobus August. Thuanus, vir cl. his

verbis: His (qui tum mortui narrabantur) annumerabo Georgium Agricolam

qui de re metallica, fossilibus, et subterraneis animantibus ita

accurate hoc saeculo scripsit: ut omnes antiquos in eo genere longe

superaverit: et exacta non solum eorum, quae a veteribus prodita sunt

explicatione; sed a multarum rerum, quas veniens aetas indagavit,

vestigatione, eam historiae naturalis partem illustraverit, addita

post Guilielmum Budaeum, Leonardum Portium, et Andream Alciatum,

ponderibus, mensuris, de pretiis metallorum et monetarum

diligentissima tractatione ac tandem anno millesimo quingentesimo,

quinquagesimo quinto, Chemnitii Hermundurorum, haud longe a maxime

famosis hoc aevo Saxonum VII. virorum agenti fodinis: ubi multa ipse

coram priscis incognita propriis oculis exploravit et observavit,

ultimum vitae diem clausit XI. Kal. Deceb. cum annum aetatis LXL

ageret. Haec ille. Id

Matthiolus ad Caspar. Naevium med. [Note: Lib. 2 epist.]

queritur, hunc praeclarum probumque senem in patria tantum terrae non

invenisse, quo suum operiretur cadaver, quod cur factum sit; Petrus

Albinus indicat. Fuerat aetate ad senium vergente Agricola valde

vehemens et pertinax in propugnanda Romana Ecclesia, eiusque

dogmatibus: qui tamen initio tum alia tum Indulgentiarum nundinationes

improbarat: ut versiculi isti ab ipso Zviccaviae anno decimo nono

compositi et publice affixi, testantur: Si

nos iniecto salvabit cistula nummo; Sed

postea quorundam Theologorum incautis scriptionibus, vitaque

Lutheranorum aliquorum scelerata offensus, inprimis εἰκονομάχια ac seditione

rusticana: reformatam religionem coepit odisse, quam antea multis in

capitibus erat amplexus: quo abduxit cum et hoc, quod natura sua

pompam Ecclesiasticam et caerimonias magni faceret; et splendori

externo fere nimium deditus esset. In

Pontificia igitur religione permanens, e vita discessit Chemnitii,

anno mense, et die ut indicavimus: cadaver autem in [Note: Zitium.]

Zeits fuit translatum, ibique in templo Cathedrali sepultum, cum dies

quinque Chemnitii inhumatum iacuisset, sub pastore Tetelhachio. Exstat

in Agricolam hunc Georgii Fabricii epigramma eiusmodi sub lemmate:

Doctrinae admirabilis. Agricola

e terris thesauros eruit omnes: Quoque

forent usu, quo pretiove, docet. Debuit

in terris vir tantus vivere; quo non Ingenium

maius patria nostra tulit. Urbe

iacet [(transcriber); sic: iabet] Citio, vitreus quam tangit Elister: Fama

viri terris intumulata manet. Lusit

in libros eiusdem idem Fabricius ita: Viderat

Agricolae, Phoebo monstrante, libellos Iuppiter:

et tales edidit ore sonos: Ex

ipso hic terrae thesauros eruet Orco: Et

fratris pandet tertia regna mei. Ioannis

Bodini de hoc iudicium omittere nolumus; quod [Note: In meth. p.

161.] eiusmodi est: Metallicam disciplinam ita tractavit Georgius

Agricola homo Germanus: ut Aristoteles ac Plinius in eo genere nihil

intellexisse videantur. Et

haec de nostro Agricola ex ipsiusmet scriptis: P. Albini Chron. Misn.

Mel. Laubani M. S. collectan. Gesn. bibliotheca, aliis. |

Georgius

Agricola (March 24, 1494 – November 21, 1555) was a German scholar and

scientist. Known as "the father of mineralogy", he was born at

Glauchau in Saxony. His real name was Georg Bauer; Agricola is the

Latinised version of his name, Bauer meaning peasant. He is best known for his

book De Re Metallica.

Gifted with a precocious intellect, Georg early threw himself into the pursuit

of the "new learning," with such effect that at the age of twenty he

was appointed Rector extraordinarius of Greek at the so-called Great School of

Zwickau, and made his appearance as a writer on philology. After two years he

gave up his appointment in order to pursue his studies at Leipzig, where, as

rector, he received the support of the professor of classics, Peter Mosellanus

(1493-1524), a celebrated humanist of the time, with whom he had already been

in correspondence. Here he also devoted himself to the study of medicine,

physics, and chemistry. After the death of Mosellanus he went to Italy from

1524 to 1526, where he took his doctor's degree.

He returned to Zwickau in 1527, and was chosen as town physician at Joachimsthal, a centre of mining and smelting works, his object being partly "to fill in the gaps in the art of healing," partly to test what had been written about mineralogy by careful observation of ores and the methods of their treatment. His thorough grounding in philology and philosophy had accustomed him to systematic thinking, and this enabled him to construct out of his studies and observations of minerals a logical system which he began to publish in 1528. Agricola's dialogue Bermannus, sive de re metallica dialogus, (1530) the first attempt to reduce to scientific order the knowledge won by practical work, brought Agricola into notice; it contained an approving letter from Erasmus at the beginning of the book.

In 1530 Prince Maurice of Saxony appointed him historiographer with an annual allowance, and he migrated to Chemnitz, the centre of the mining industry, in order to widen the range of his observations. The citizens showed their appreciation of his learning by appointing him town physician in 1533. In that year, he published a book about Greek and Roman weights and measures, De Mensuris et Ponderibus.

He was also elected burgomaster of Chemnitz. His popularity was, however, short-lived. Chemnitz was a violent centre of the Protestant movement, while Agricola never wavered in his allegiance to the old religion; and he was forced to resign his office. He now lived apart from the contentious movements of the time, devoting himself wholly to learning. His chief interest was still in mineralogy; but he occupied himself also with medical, mathematical, theological and historical subjects, his chief historical work being the Dominatores Saxonici a prima origine ad hanc aetatem, published at Freiberg. In 1544 he published the De ortu et causis subterraneorum, in which he laid the first foundations of a physical geology, and criticized the theories of the ancients. In 1545 followed the De natura eorum quae effluunt e terra; in 1546 the De veteribus et novis metallis, a comprehensive account of the discovery and occurrence of minerals and also more commonly known as De Natura Fossilium; in 1548 the De animantibus subterraneis; and in the two following years a number of smaller works on the metals.

De Re Metallica

His most famous work, the De re metallica libri xii, was published in 1556, though apparently finished several years before, since the dedication to the elector and his brother is dated 1550. It is a complete and systematic treatise on mining and metallurgy, illustrated with many fine and interesting woodcuts which illustrate every conceivable process to extract ores from the ground and metal from the ore, and more besides. Thus Agricola describes and illustrates how ore veins occur in and on the ground, making the work an early contribution to the developing science of geology. He describes prospecting for ore veins and surveying in great detail, as well as washing the ores to collect the heavier valuable minerals such as gold and tin.

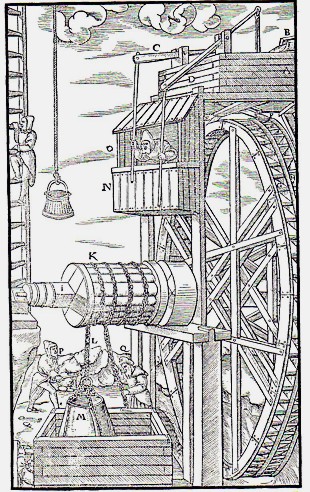

De re metallica - A water mill used for raising ore

It is also interesting for showing the many water mills used in mining, such as the machine for lifting men and material into and out of a mine shaft. Water mills found innumerable applications, especially in crushing ores to release the fine particles of gold and other heavy minerals, as well as working giant bellows to force air into the confined spaces of underground workings.

It contains in an appendix the German equivalents for the technical terms used in the Latin text. It long remained a standard work, and marks its author as one of the most accomplished chemists of his time. Believing the black rock of the Schlossberg at Stolpen to be the same as Pliny the Elder's basalt, he applied this name to it, and thus originated a petrological term which has been permanently incorporated in the vocabulary of science. Until that time, Pliny's work Historia Naturalis was the main source of information on metals and mining techniques, and Agricola makes numerous references to the Roman encyclopedia.

He describes many mining methods which are now redundant, such as fire-setting, which involved building fires against hard rock faces. The hot rock was quenched with water and the thermal shock weakened it enough for easy removal. It was very dangerous when used in underground galleries for the toxic gases given off by fires, and was made obsolete by explosives.

De re metallica - Fire-setting underground

De re metallica is considered a classic document of Medieval metallurgy, unsurpassed for two centuries. In 1912, the Mining Magazine (London) published an English translation. The translation was made by Herbert Hoover, an American mining engineer better known in his term as a President of the United States, and his wife Lou Henry Hoover.

Final days

In spite of the early proof that Agricola had given of the tolerance of his own religious attitude, he was not suffered to end his days in peace. He remained to the end a staunch Catholic, though all Chemnitz had gone over to the Lutheran creed; and it is said that his life was ended by a fit of apoplexy brought on by a heated discussion with a Protestant divine. He died in Chemnitz on 21 November 1555; so violent was the theological feeling against him, that he was not allowed to be buried in the town to which he had added such lustre. Amidst hostile demonstrations he was carried to Zeitz, some sixty kilometers northwest, and buried there.

Georgius Agricola (* 24. März 1494 in Glauchau; † 21. November 1555 in Chemnitz), mit bürgerlichem Namen Georg Pawer bzw. Bauer (sein Professor in Leipzig Petrus Mosellanus riet ihm, seinen Namen zu latinisieren), war ein Wissenschaftler, Humanist und Arzt, und wird auch als Vater der Mineralogie bezeichnet.

Agricola wurde 1494, als zweites von sieben Kindern eines Tuchmachers und Färbers in Glauchau geboren. Er studierte von 1514 bis 1518 alte Sprachen an der Universität Leipzig bei Petrus Mosellanus (1493–1524), einem Anhänger Erasmus’ von Rotterdam, der ihn anschließend in Zwickau empfahl. So wurde Agricola dort zuerst Konrektor (1518), dann Rektor der Zwickauer Ratsschule (1519) und schuf einen neuen Schultyp mit Latein, Griechisch und Hebräisch-Unterricht in Kombination mit Gewerbekunde: Ackerbau, Weinbau, Bau- und Messwesen, Rechnen, Arzneimittelkunde und Militärwesen.

Nachdem Agricola 1522 erneut in Leipzig studierte, diesmal Medizin, ging er 1523 an die Universitäten von Bologna und Padua. 1524 begab er sich nach Venedig, um im Verlag Aldus Manutius die Galen-Ausgabe zu bearbeiten. 1526 kehrte er nach Chemnitz zurück.

Im Jahre 1527 heiratete Agricola die Witwe Anna Meyner aus Chemnitz und ließ sich nun als Arzt und Apotheker in St. Joachimsthal (heute: Jáchymov) nieder. 1531 wurde er Stadtarzt in Chemnitz, dort hatte er viermal das Bürgermeisteramt inne (1546, 1547, 1551 und 1553). Zudem war er im Staatsdienst als sächsischer Hofhistoriograph beschäftigt. Als Universalgelehrter forschte Agricola im Bereich der Medizin, Pharmazie, Alchimie, Philologie und Pädagogik, Politik und Geschichte, Metrologie, Geowissenschaften und Bergbau. Agricola verband humanistische Gelehrsamkeit mit technischen Kenntnissen.

So entstand sein Erstlingswerk Bermannus, sive de re metallica (1530), in dem er Verfahren zur Erzfindung und -verarbeitung sowie Metallgewinnung ebenso beschreibt wie die Fortschritte der Bergbautechnik, das Vermessungswesen (Markscheidewesen), den Transport, die Aufbereitung und die Verarbeitung der Erze. In De Mensuris et ponderibus von 1533 beschreibt er die griechischen und römischen Maße und Gewichte – seinerzeit gab es keine einheitlichen Maße, was den Handel erheblich behinderte. Dieses Werk legte den Grundstein für Agricolas Ruf als humanistischer Gelehrter.

Mit mehreren Werken begründete Agricola die Geowissenschaften: So beschreibt er die Entstehung der Stoffe im Erdinneren in De ortu et causis subterraneorum von 1544, die Natur der aus dem Erdinneren hervorquellenden Dinge in seinem Werk De natura eorum, quae effluunt ex terra von 1545, Mineralien in De natura fossilium sowie die Erzlagerstätten und den Erzbergbau in alter und neuer Zeit (De veteribus et novis metallis). Auch der Meurer-Brief (Epistula ad Meurerum) von 1546 gehört zu diesen Werken.

Agricola war zweimal verheiratet und hatte (mindestens) sechs Kinder. Zwei Jahre nachdem seine erste Frau 1540 starb, heiratete der 48jährige Stadtarzt die 30 Jahre jüngere Tochter Anna des ehemaligen Besitzers der Kupfersaigerhütte Ulrich Schütz d. J.. Er heiratete in die damals reichste Familie von Chemnitz ein. Am 21. November 1555, im Alter von 61 Jahren, starb er in Chemnitz. Nach der Reformation in Sachsen verweigerte die Stadt dem katholischen Agricola die Beerdigung auf Chemnitzer Flur. Daraufhin wurde er in der Schlosskirche von Zeitz begraben, was auf die Initiative seines Freundes, des Gelehrten und Bischofs Julius Pflugk von Zeitz, geschah.

Hauptwerk – De re metallica libri XII

Durch zahlreiche Reisen im Bergbaurevier des sächsischen und böhmischen Erzgebirges gewann Agricola einen Überblick über die gesamte Technik des Bergbaus und Hüttenwesens zu seiner Zeit. Das Ergebnis ist sein Hauptwerk: Das Buch der Metallkunde De re metallica libri XII erschien 1556 ein Jahr nach seinem Tod in lateinischer Sprache in Basel. Später wurde es in zahlreiche andere Sprachen übersetzt. Philippus Bechius, ein Freund Agricolas und Professor an der Universität Basel, übertrug die Schrift ins Deutsche und veröffentlichte sie 1557 unter dem Titel Vom Bergkwerck XII Bücher. Es handelte sich um die erste systematische technologische Untersuchung des Bergbau- und Hüttenwesen und blieb zwei Jahrhunderte lang das maßgebliche Werk zu diesem Thema.

Der erste Band stellt eine zeitgemäße Apologie dar und vergleicht mit anderen Gewerben, beispielsweise der Landwirtschaft oder dem Handel. Im zweiten Band werden die Erschließungsbedingungen erörtert, also geographische Beschaffenheit, Wasserhaltung, Wege, Bodenbesitz und Landesherrschaft; im dritten Band das Markscheidewesen. Der vierte Band äußert sich zur Verteilung der Grubenfelder und den Pflichten des Bergebamten. Im fünften Band werden die verschiedenen Schachtarten und ihr Ausbau beschrieben, zudem der Gangbau und das Vermessen unter Tage. Der sechste ist der umfangreichste Band, er behandelt die Geräte und Maschinen des Bergbaus. Das Probieren der Erze findet sich im siebten Band, ihr Aufbereitungsprozeß im achten Band. Das Schmelzen und die Verfahren zur Metallgewinnung inklusive einer Anleitung zum Schmelzofenbau findet sich im neunten Band. In den Bänden zehn, elf und zwölf geht es dann noch um das Scheiden von Edelmetallen, das Gewinnen von Salzen, Schwefel und Bitumen sowie um Glas.

Im Gesamtwerk stehen ausschließlich objektive Eigenschaften zur Diskussion, alle Überlieferungen und alchemistischen Aussagen werden auf ihren Wahrheitsgehalt untersucht. Mangels einheitlicher Maße nimmt Agricola bezug zu bekannten Angaben:

„Bei kleinen, mittleren oder groben Zinnerzstücken braucht der erfahrene Schmelzer … wenn er die ersten verschmilzt, nur langsam Feuer, wenn die zweiten, mittleres, wenn die dritten, scharfes; jedoch viel weniger scharfes, als wenn er Gold-, Silber- oder Kupfererz verschmilzt.“

oder

„… man habe noch so lange zu erhitzen als einer braucht fünfzehn Schritte zu gehen.“

Die Beschreibungen der Minerale bauen auf den Werken von Avicenna und Albertus Magnus auf.

Dieses Buch der Metallkunde war auch Francis Bacon bekannt, aus dem er wichtige Anregungen entnahm. Es enthält neben einer modernen Theorie der Entstehung von Metalladern in Erzgestein allerdings auch Abschnitte über Kobolde und Drachen in den Gruben, die er „Lebewesen unter Tage“ (De animantibus subterraneis) nannte.

Postume Ehrung

1926 gründen Oskar von Miller, Schöpfer des Deutschen Museums, und Conrad Matschoß, Direktor des Vereins Deutscher Ingenieure und Nestor der deutschen Technikgeschichtsschreibung, die Georg-Agricola-Gesellschaft beim Deutschen Museum. Erstes Ziel der Gesellschaft ist die Herausgabe der ersten modernen deutschen Ausgabe von Agricolas Hauptwerk.

1960 konstituiert sich beim Verein Deutscher Ingenieure – unter maßgeblicher Beteiligung des Deutschen Verbandes Technisch-Wissenschaftlicher Vereine e.V. und der Montanindustrie – die „Georg-Agricola-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik e.V.

Die Universitätsbibliothek der TU Bergakademie Freiberg wurde 1981 nach Georgius Agricola benannt. Seit dem Jahr 1995 trägt die Fachhochschule Bergbau in Bochum den Namen Technische Fachhochschule Georg Agricola. Auch das Krankenhaus in Zeitz, wo er im sog. Dom St. Peter und Paul, der Schlosskirche begraben liegt, ist nach ihm benannt. Eine Studentenverbindung mit Sitz in Aachen und Clausthal-Zellerfeld gab sich 1948 den Namen Akademischer Verein Agricola Schlägel und Eisen und änderte ihn später in Agricola Akademischer Verein. Die Westsächsische Hochschule Zwickau besitzt einen Georgius-Agricola-Bau. In Glauchau und Chemnitz gibt es ein Georgius-Agricola-Gymnasium. In der Stadt Zeitz (Sachsen-Anhalt) ist eine Straße nach Georgius Agricola benannt, wodurch der Universalgelehrte und Freund des Zeitzer Bischofs Julius Pflugk geehrt wird.

Veröffentlichungen

Bermannus sive de re metallica, Basel 1530 (Digitalisat) (Nachdruck: Belles Lettres, Paris 1990, ISBN 2-251-34504-3)

De bello adversus Turcas, Nürnberg 1531 (Digitalisat/PDF)

De mensuris et ponderibus libri V, Paris 1533 (Digitalisat Ausg. Venedig 1535)

Oratio de bello adversus Turcam Suscipiendo, Basel 1538 (Digitalisat/PDF)

De re metallica, Ausgabe Paris 1541 (Vorwort von Erasmus) (Digitalisat/PDF)

De ortu et causis subterraneorum libri V, Basel 1546 Sammelwerk (Digitalisat Ausg. Basel 1558)

De natura eorum, quae effluunt ex terra, Basel 1546 (Nachdruck: SNM, Bratislava 1996, ISBN 80-85753-91-X)

De veteribus et novis metallis libri II, Basel 1546

De natura fossilium libri X., Basel 1546 ("Digitalisat Engl. Übers. v. Bandy 1955) (Nachdruck: Dover Publ., Mineola, N.Y. 2004, ISBN 0-486-49591-4)

De animantibus subterraneis liber, Basel 1549 (Nachdruck: VDI-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1978, ISBN 3-18-400400-7)

De mensuris quibus intervalla metimur liber, 1550 (Digitalisat)

De precio metallorum et monetis liber III, 1550

De peste libri tres Basel 1554 (Digitalisat)

De re metallica libri XII, Basel 1556 (Digitalisat/Transkript) (Digitalisat Ausg. 1561) ( Digitalisat Dt. Übers. v. Schiffner 1928) (Digitalisat Engl. Übers v. Hoover 1912)

Dictionnaire

historique

de la médecine ancienne et moderne

par Nicolas François Joseph Eloy

Mons – 1778