Lessico

Fozio

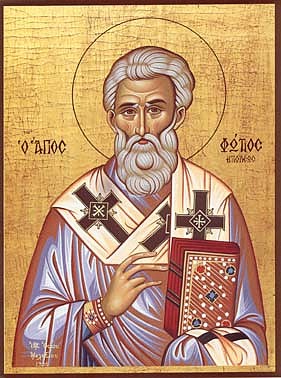

Fozio I di Costantinopoli detto il Grande (Costantinopoli, 820 circa – Armenia, 6 febbraio 898), è stato un bibliografo e patriarca bizantino che in greco suonava Phøtios che si potrebbe magari tradurre con Figlio della Luce. Fu patriarca di Costantinopoli per ben due volte: la prima dal Natale dell'anno 858 all'867; la seconda dal 877 fino al 886. È venerato come santo dalla chiesa cristiana ortodossa. Venne alla luce mentre la sua famiglia si trovava in visita a Costantinopoli, città della quale era patriarca suo zio Niceforo I di Costantinopoli. La sua famiglia godeva di autorità a Costantinopoli: il padre si chiamava Sergio ed era capo della guardie imperiali.

Gli inizi

Fozio ebbe un'ottima educazione, fu molto apprezzato come uomo di vasta cultura, filologo, esegeta ed esperto della Patristica, e i genitori decisero per lui che avrebbe intrapreso una vita da laico. Divenne così docente di filosofia e teologia e successivamente uomo di Stato. Grazie alla parentela con la famiglia Imperiale, poté conseguire incarichi di grande responsabilità, in quanto suo fratello aveva sposato la zia dell'Imperatore Teofilo II di Bisanzio e, grazie a questo appoggio, Fozio occupò in breve tempo posizioni di altissimo prestigio, come quello di Segretario Capo di Stato e Capitano delle guardie del corpo dell'Imperatore.

Fozio I Patriarca di Costantinopoli

L'imperatore Michele III di Bisanzio, detto l'Ubriaco (836 - 867), succedette al padre Teofilo II di Bisanzio nel 842 a soli 6 anni d'età. Non potendo occuparsi degli affari di Stato a causa della minore età - Michele III aveva appunto solo 6 anni quando si ritrovò Imperatore di Bisanzio - la reggenza dell'Impero fu affidata alla madre, l'Imperatrice Teodora, che rimase in carica fino al 858. Fra i diversi atti della sua reggenza ci fu in particolare la comminatoria dell'esilio al patriarca Ignazio I di Costantinopoli, con il pretesto di aver rifiutato di dare la comunione allo zio dell'Imperatore, Bardas.

Teodora aveva dunque bisogno di nominare un nuovo patriarca di Costantinopoli, e fu scelto Fozio, a quell'epoca ancora un laico. Per realizzare tale risultato, Teodora lo nominò vescovo dopo soli cinque giorni dall'esilio del patriarca Ignazio e, nel Natale dello stesso anno 858, Fozio fu nominato patriarca di Costantinopoli. Ma la situazione non si rivelò così semplice da risolvere, dato che Ignazio non ebbe la minima intenzione di rinunciare placidamente al seggio patriarcale. Si recò allora a Roma, dove chiese e ottenne un colloquio con il Papa Niccolò I detto il Magno (858-867); quest'ultimo fu subito pronto ad appoggiare Ignazio e, a tal fine, convocò immediatamente un sinodo che si tenne nel 863 a Roma, durante il quale fu dichiarato:

- che il

Papa non riconosceva la deposizione di Ignazio

- che venivano altresì scomunicati i legati papali, da lui inviati a

Costantinopoli nell'861 per decidere sulla questione e che, invece, si erano

fatti corrompere

- che, di conseguenza, Fozio veniva scomunicato, se avesse insistito

nell'usurpazione del seggio patriarcale.

Fozio non gradì l'affronto di una possibile scomunica e a sua volta con l'appoggio dell'Imperatore Michele III scomunicò il Papa nell'867. Fozio inviò un'enciclica a tutti i vescovi bizantini, spiegando alcuni punti di divergenza con la Chiesa di Roma, la quale a seguito di una serie di riforme impose:

-

l'aggiunta del Filioque al credo, estendendo la dottrina trinitaria

greca secondo cui lo Spirito Santo procede dal Padre ma anche dal Figlio

- il celibato per i preti, cosa non prevista nella chiesa ortodossa

- l'esclusiva dei vescovi di celebrare la Cresima

- il digiuno per tutto il clero al sabato.

- la fissazione dell'inizio della quaresima al mercoledì delle ceneri.

La prima deposizione

Ma sempre nell'867 successe un fatto che avrebbe cambiato le sorti dell'Impero bizantino. Michele III fu assassinato e al suo posto divenne Imperatore il suo carnefice, Basilio I di Bisanzio (867-886), fondatore della Dinastia macedone. Basilio tolse a tutti coloro che avevano alte cariche sotto Michele il loro impiego e designò altri dignitari di sua fiducia. Al fine di giungere a un accordo con Roma, anche Fozio fu deposto dal suo incarico di Patriarca e Ignazio fu reinstallato al suo posto. Questo avvenimento, con il relativo riavvicinamento della Chiesa d'Oriente a Roma, fu suggellato dal Concilio di Costantinopoli dell'869, voluto da Papa Adriano II (867-872). Fozio fu esiliato in un monastero sul Bosforo, ma con molta probabilità a Cherson in Crimea. Dopo alcuni anni Basilio I richiamò a corte Fozio f il suo compito fu di fare da precettore a Costantino, uno dei figli dell'Imperatore.

Il secondo mandato patriarcale di Fozio

Nell'877 Ignazio I di Costantinopoli morì e si pose il problema di individuare un sostituto per il Patriarcato sul Bosforo. Basilio I di Bisanzio decise allora di rinominare Fozio quale patriarca di Costantinopoli, visto che era una persona molto popolare nella capitale e tutti lo conoscevano di fama. Persino Papa Giovanni VIII (872-882) ne approvò la nomina.

Fozio raggiunse il culmine del suo trionfo con il Concilio di Costantinopoli dell'879-880, dove revocò le decisioni del precedente Concilio dell'869, nel corso del quale era stato fatto patriarca Ignazio, e riaprì i punti di controversia dottrinale e teologica con Roma. Nel corso dello stesso Concilio, Fozio fece altresì dichiarare ai vescovi che la Bulgaria, dove nell'865 il re Boris aveva indicato il cristianesimo come religione di Stato, doveva far parte della sfera d'influenza religiosa - e quindi politica - del Patriarcato di Costantinopoli e che pertanto le era vietata la creazione di un autonomo patriarcato. Papa Giovanni VIII scomunicò immediatamente Fozio, ma tale scomunica non ebbe alcun effetto, se non quello di creare una maggiore divisione tra la Chiesa d'occidente e quella d'oriente.

La seconda deposizione

Nell'886 salì al trono di Bisanzio un nuovo Imperatore, Leone VI di Bisanzio, detto il Filosofo (886-912), che con alcune accuse senza fondamento verso Fozio lo fece deporre per nominare al suo posto il fratello dell'Imperatore, Stefano I di Costantinopoli. Questa procedura fu ritenuta irregolare da Papa Stefano V (885-891) e perciò quest'ultimo lanciò un'ulteriore scomunica diretta al nuovo patriarca di Costantinopoli.

La fine

Fozio, dopo essere stato deposto e bandito da corte, fu fatto segregare in un monastero in Armenia per ordine dell'Imperatore. La morte lo colse nell'897, mentre ancora si trovava segregato nel monastero armeno in cui fu mandato in esilio. Fozio aveva posto le basi teologiche e politiche per lo Scisma d'Oriente, che avvenne nel 1054, un secolo e mezzo dopo di lui. In seguito fu proclamato santo dalla Chiesa Ortodossa.

Opere letterarie di Fozio

Fozio fu

molto importante per la storia del diritto di ogni paese europeo, contribuendo

fortemente all'opera di elaborazione di testi normativi emanati da Basilio I

di Bisanzio, e poi dal figlio Leone VI di Bisanzio, I Basilici. Fozio

contribuì anche molto alla storia della letteratura bizantina. Egli fu molto

importante per la storia e la preservazione della letteratura greca classica,

grazie, in particolare, alla realizzazione di uno dei massimi repertori

bibliografici che ci siano giunti dall'Alto Medio Evo, la Bibliotheca![]() . Per gli

studiosi dell'antichità classica è un'opera di fondamentale importanza.

. Per gli

studiosi dell'antichità classica è un'opera di fondamentale importanza.

Aggiunta dall'Enciclopedia De Agostini - Delle sue opere, oltre all'Epistolario, ricco di testimonianze sull'uomo e il suo tempo, alle Omelie e ai Sermoni, si ricordano soprattutto il Lexicon, la Bibliotheca e l'Amphilochia. Il Lexicon s'inserisce nella grande tradizione glossografica risalente all'ellenismo. La Bibliotheca (titolo originale Myriobiblon) è una rassegna di 279 opere, riassunte e (per la prima volta nella storia) “recensite”, in base a un gusto letterario atticistico e alla sensibilità di cristiano ortodosso dell'autore. Composta forse nell'838, l'opera è un repertorio di fondamentale importanza per la conoscenza della letteratura greca. L'Amphilochia, ritenuta, a differenza delle precedenti, un'opera della vecchiaia di Fozio, è una raccolta di 300 quaestiones, per lo più religiose, dirette ad Anfilochio, metropolita di Cizico, antica città dell'Asia Minore, nella Misia.

La Bibliotheca

(anche nota come Myriobiblon, "mille libri") è una rassegna

bizantina di opere letterarie greche e bizantine redatta dal patriarca Fozio I

di Costantinopoli. È una raccolta di notizie ed epitomi (ossia riassunti) di

altri testi, tra i quali vi sono diverse opere di Erodoto![]() e del

patriarca Niceforo I di Costantinopoli (806-815). Le epitomi, che sono 279,

sono chiamate codici. L'opera inizia e si conclude con due lettere di Fozio

spedite al fratello Tarasio. Per molti autori antichi, le epitomi raccolte

nella Bibliotheca costituiscono tutto ciò che oggi resta delle loro

opere: un esempio sono i romanzi di Antonio Diogene (scrittore greco forse del

sec. I aC) e di Giamblico

e del

patriarca Niceforo I di Costantinopoli (806-815). Le epitomi, che sono 279,

sono chiamate codici. L'opera inizia e si conclude con due lettere di Fozio

spedite al fratello Tarasio. Per molti autori antichi, le epitomi raccolte

nella Bibliotheca costituiscono tutto ciò che oggi resta delle loro

opere: un esempio sono i romanzi di Antonio Diogene (scrittore greco forse del

sec. I aC) e di Giamblico![]() .

.

In quest'opera sono rappresentati solo autori di prosa. Gli autori epitomizzati sono sia cristiani che pagani. La letteratura cristiana è la più trattata nella Bibliotheca, con 157 codici che vi fanno riferimento, mentre la letteratura pagana occupa gli altri 122 codici. L'opera non presenta le opere in ordine cronologico, né in alcun altro ordine globale riconoscibile. è tuttavia possibile ricostruire al suo interno alcuni raggruppamenti:

Atti dei

Concili: codici dal 15 al 20 e dal 52 al 54.

Storie ecclesiastiche: codici dal 27 al 31 e dal 40 al 42.

Storiografia: codici dal 33 al 35, dal 57 al 58, dal 62 al 72, dal 76 al 80,

dal 82 al 84, dal 91 al 93 e dal 97 al 99.

Scritti antiereticali: codici dal 120 al 123.

Lessici: codici dal 145 al 158.

Mitografia e paradossografia: codici dal 186 al 190.

Medicina: codici dal 216 al 221.

Oratoria: codici dal 259 al 268.

Dioscoride![]() appartiene al codice 178

appartiene al codice 178![]() .

.

L'incipit di ciascun codice costituisce una presentazione quasi bibliografica dell'autore trattato; segue un breve riassunto dell'opera redatto da Fozio; il codice si conclude poi con valutazioni morali e stilistiche e con confronti tra l'autore e altri esponenti dello stesso genere letterario.

Per molti autori e filosofi antichi, la Bibliotheca rappresenta l'unico veicolo tramite il quale il loro pensiero è stato trasmesso ai tempi odierni. Due romanzi in particolare devono all'opera di Fozio la sopravvivenza del proprio ricordo:

- Il Dramaticon di Giamblico. Fozio lesse questo racconto drammatico, che narra storie d'amore, e ne riportò nella sua opera un'epitome, che costituisce l'unica testimonianza sull'opera.

- Le incredibili meraviglie al di là di Thule di Antonio Diogene, in ventiquattro libri.

Inoltre,

le indicazioni di Fozio permettono agli storiografi attuali di ricostruire

dati di moltissime opere delle epoche classica, greca e bizantina; dei 122

autori menzionati da Fozio, 90 sono pressoché perduti; Fozio è perciò un

testimone fondamentale per ricostruirne il pensiero e le opere. In altri casi,

le schede di Fozio testimoniano un tipo di divisione delle opere altrimenti

non pervenuta nei manoscritti originali: è il caso delle Vite di

Plutarco![]() o della

trasmissione delle orazioni attiche.

o della

trasmissione delle orazioni attiche.

Photios I (Greek: Phøtios; c. 810 – c. 893) also spelled Photius or Fotios and known by the Eastern Orthodox Church as St. Photios the Great, was Patriarch of Constantinople from 858 to 867 and from 877 to 886. Photios is widely regarded as the most powerful and influential Patriarch of Constantinople since John Chrysostom, and as the most important intellectual of his time, "the leading light of the ninth-century renaissance". He was a central figure in both the conversion of the Slavs to Christianity and the estrangement of the Eastern and Western Churches. Photios is recognized as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church and some of the Eastern Catholic Churches of Byzantine tradition. His feast is celebrated on 6 February.

Photios was a well-educated man from a noble Constantinopolitan family. He intended to be a monk, but chose to be a scholar and statesman instead. In 858, Emperor Michael III deposed Ignatius, Patriarch of Constantinople, and Photios, still a layman, was appointed in his place. Amid power struggles between the Pope and the Emperor, Ignatius was reinstated. Photios resumed the position when Ignatius died (877), by order of the Emperor. Roman Catholics regard an Ecumenical Council anathematizing Photios as legitimate. Eastern Orthodox regard a second council, reversing the first, as legitimate. The contested Ecumenical Councils mark the end of unity represented by the first seven Ecumenical Councils.

Secular life

Most of the primary sources treating Photios' life are written by persons hostile to him. Modern scholars are thus cautious, when assessing the accuracy of the information these sources provide. Little is known of Photios' and origin and early years. We do know that he was born into a notable family; his uncle Tarasios had been patriarch from 784–806 under both Irene and Nikephoros I. During the second Iconoclasm his family suffered persecution since his father, Sergios, was a prominent iconophile. Sergios's family returned to favor only after the restoration of the icons in 842. Certain scholars assert that Photios was, at least in part, of Armenian descent. Byzantine writers also report that Emperor Michael III once angrily called Photios "Khazar-faced", but whether this was a generic insult or a reference to his ethnicity is unclear.

Although Photios had an excellent education, we have no information about how he received this education. The famous library he possessed attests to his enormous erudition (theology, philosophy, grammar, law, the natural sciences, and medicine). Most scholars believe that he never taught at Magnaura or at any other university; Vasileios N. Tatakis asserts that, even while he was patriarch, Photios taught "young students passionately eager for knowledge" at his home, which "was a center of learning".

Photius says that, when he was young, he had an inclination for the monastic life, but instead he started a secular career. The way to public life was probably opened for him by (according to one account) the marriage of his brother Sergios to Irene, a sister of the Empress Theodora, who upon the death of her husband Theophilos in 842, had assumed the regency of the empire. Photios became a captain of the guard (prøtospatharios) and subsequently chief imperial secretary (prøtasëkrëtës). At an uncertain date, Photios participated in an embassy to the Abbasids of Baghdad.

Patriarch of Constantinople

Photios' ecclesiastical career took on spectacularly after Caesar Bardas and his nephew, the youthful Emperor Michael, put an end to the administration of the regent Theodora and the logothete of the drom Theoktistos in 856. In 858 Bardas found himself opposed by the then Patriarch Ignatios, who refused to admit him into Hagia Sophia, since it was believed that he was having an affair with his widowed daughter-in-law. In response, Bardas and Michael engineered Ignatios's deposition and confinement on the charge of treason, thus leaving the patriarchal throne empty. The throne was soon filled with a Bardas's kinsman, Photios himself; he was tonsured on December 20, 858, and on the four following days he was successively ordained lector, sub-deacon, deacon and priest. He was consecrated as Patriarch of Constantinople on Christmas.

The deposition of Ignatios and the sudden promotion of Photios caused scandal and ecclesiastical division on an oecumenical scale, for Rome took up the cause of Ignatios. The latter's deposition without a formal ecclesiastical trial meant that Photios election was uncanonical, and eventual Pope Nicholas I, as senior patriarch, sought to involve himself in determining the legitimacy of the succession. His legated were dispatched to Constantinople with instructions to investigate, but finding Photios well ensconced, they acquiesced in the confirmation of his election at a synod in 861. On their return to Rome, they discovered that this was not at all what Nicholas had intended, and in 863 at a synod in Rome the pope deposed Photios, and reappointed Ignatius as the rightful patriarch. Four years later, Photios was to respond on his own part, excommunicating the pope on grounds of heresy — over the question of the double procession of the Holy Spirit. The situation was additionally complicated by the question of papal authority over the entire Church and by disputed jurisdiction over newly-converted Bulgaria.

This state of affairs changed with the murder of Photios' patron Bardas in 866 and of the emperor Michael in 867, by his colleague Basil the Macedonian, who now usurped the throne. Photios was deposed as patriarch, not so much because he was a protegé of Bardas and Michael, but because Basil I was seeking an alliance with the Pope and the western emperor. Photios was removed from his office and banished about the end of September 867, and Ignatios was reinstated on November 23. Photios was condemned by the Council of 869–870. During his second patriarchate, Ignatios followed a policy not very different from that of Photios.

Not long after his condemnation Photios had reingratiated himself with the Basil, and became tutor to the emperor's children. From surviving letters of Photios written during his exile at the Skepi monastery it appears that the ex-patriarch brought pressure to bear on the emperor to restore him. Ignatios's biographer argues that Photios forged a document relating to the genealogy and rule of Basil's family, and had it placed in the imperial library where a friend of his was librarian. According to this documents, the emperor's ancestors were not mere peasants as everyone believed but descendants of the Arsacid Dynasty of Armenia. True or not this story does reveal Basil's dependence on Photios for literary and ideological matters. Photios is even said to have prepared a genealogy, showing the emperor's ancestors were not peasants as everyone had thought, but following Photios's recall Ignatios and the ex-patriarch met, and publicly expressed their reconciliation. When Ignatios died on October 23, 877, it was a matter of course that his old opponent replaced him on the patriarchal throne three days later. Shaun Tougher asserts that from this point on Basil no longer simply depended on Photios, but in fact he was dominated by him.

Photios now obtained the formal recognition of the Christian world in a council convened at Constantinople in November 879. The legates of Pope John VIII attended, prepared to acknowledge Photios as legitimate patriarch, a concession for which the pope was much censured by Latin opinion. The patriarch stood firm on the main points contested between the Eastern and Western Churches, the demanded apology to the Pope, the ecclesiastical jurisdiction over Bulgaria, and the introduction of the Filioque clause into the creed. Eventually Photios refused to apologize or accept the Filioque, and the papal legates made do with his return of Bulgaria to Rome. This concession, however, was purely nominal, as Bulgaria's return to the Byzantine rite in 870 had already secured for it an autocephalous church. Without the consent of Boris I of Bulgaria, the papacy was unable to enforce its claims.

During the altercations between Basil I and his heir Leo VI, Photios took the side of the emperor. In 883 Basil accused Leo of conspiracy and confined the prince to the palace; he would have even blinded him had he not been dissuaded by Photios and Stylianos Zautzes, the father of Zoe Zaoutzaina, Leo's mistress. In 886 Basil discovered and punished a conspiracy by the domestic of the Hicanati John Kourkouas and many other officials. In this conspiracy Leo was not implicated, but Photios was possibly one of the conspirators against Basil's authority.

Basil died in 886 injured while hunting, according to the official story. Warren T. Treadgold believes that this time the evidence points to a plot on behalf of Leo, who became emperor, and dismissed Photios, although the latter had been his tutor. He was replaced by the emperor's brother Stephen, and sent into exile to the monastery of Bordi in Armenia. It is confirmed from letters to and from Pope Stephen that Leo extracted a resignation from Photios. In 887 Leo was put on trial for treason, but no conviction against the ex-patriarch had been secured; the main witness, Theodore Santabarenos, refused to testify that Photios was behind Leo's removal from power in 883, and faced after the trial the emperor's wrath. As a persona non grata Photios probably returned to his enforced monastic retirement. Yet it appears that he did not remain reviled for the remainder of his life.

Photios continued his career as a writer in the reign of Leo who probably rehabilitated his reputation within the next few years; in his Epitaphios on his brothers, a text probably written in 888, the emperor presents Photios favorably, portraying him as the legitimate archbishop, and the instrument of ultimate unity, an image that jars with his attitude to the patriarch in 886–887. Confirmation that Photios was rehabilitated comes upon his death: according to some chronicles his body was permitted to be buried in Constantinople. In addition, according to the anti-Photian biographer of Ignatius, partisans of the ex-patriarch after his death endeavored to claim for him the "honor of sainthood". Further, a leading member of Leo's court, Leo Choirospaktes, wrote poems commemorating the memory of several prominent contemporary figures, such as Leo the Mathematician and the Patriarch Stephen, and he also wrote one on Photios. Shaun Tougher notes, however, that "yet Photios' passing does seem rather muted for a great figure of Byzantine history [...] Leo [...] certainly did not allow him back into the sphere of politics, and it is surely his absence from this arena that accounts for his quiet passing."

For the Eastern Orthodox, Photios was long the standard-bearer of their church in its disagreements with the pope of Rome; to Catholics, he was a proud and ambitious schismatic: the relevant work of scholars over the past generation has somewhat modified partisan judgments. All agree on the virtue of his personal life and his remarkable talents, even genius, and the wide range of his intellectual aptitudes. Pope Nicholas himself referred to his "great virtues and universal knowledge." It may be noted, however, that some anti-papal writings attributed to Photios were apparently composed by other writers about the time of the East-West Schism of 1054 and attributed to Photios as the champion of the independence of the Eastern Church.

The Eastern Orthodox Church venerates Photios as a saint; he is also included in the liturgical calendar of Eastern Catholic Churches of Byzantine Rite, though not in the calendars of other Eastern Catholic Churches. His feast day is February 6.

Assessments

Photios is one of the most famous figures not only of the ninth-century Byzantium but of the entire history of the Byzantine Empire. One of the most learned men of his age, he has earned his fame due to his part in ecclesiastical conflicts, and also for his intellect and literary works. Analysing his intellectual work, Tatakis regards Photios as "mind turned more to practice than to theory". He believes that, thanks to Photios, humanism was added to Orthodoxy as a basic element of the national consciousness of the Byzantines. Tatakis also argues that, having understood this national consciousness, Photios emerged as a defender of the Greek nation and its spiritual independence in his debates with the Western Church. Adrian Fortescue regards him as "the most wonderful man of all the Middle Ages", and stresses that "had not given his name to the great schism, he would always be remembered as the greatest scholar of his time".

Writings

The

most important of the works of Photios is his renowned Bibliotheca or Myriobiblon![]() , a

collection of extracts and abridgments of 280 volumes of classical authors (usually

cited as Codices), the originals of which are now to a great extent

lost. The work is especially rich in extracts from historical writers.

, a

collection of extracts and abridgments of 280 volumes of classical authors (usually

cited as Codices), the originals of which are now to a great extent

lost. The work is especially rich in extracts from historical writers.

There has been discussions on whether the Bibliotheca was in fact compiled in Baghdad at the time of Photius' embassy to the Abbasid court in Samarra in June 845, since many of the mentioned works - the majority by secular authors - seems to have been virtually nonexistent in both contemporary and later Byzantium. The Abbasids showed great interest in classical Greek works and Photius might have studied them during his years in exile in Baghdad.

To Photios we are indebted for almost all we possess of Ctesias, Memnon, Conon, the lost books of Diodorus Siculus, and the lost writings of Arrian. Theology and ecclesiastical history are also very fully represented, but poetry and ancient philosophy are almost entirely ignored. It seems that he did not think it necessary to deal with those authors with whom every well-educated man would naturally be familiar. The literary criticisms, generally distinguished by keen and independent judgment, and the excerpts vary considerably in length. The numerous biographical notes are probably taken from the work of Hesychius of Miletus.

The Lexicon, published later than the Bibliotheca, was probably in the main the work of some of his pupils. It was intended as a book of reference to facilitate the reading of old classical and sacred authors, whose language and vocabulary were out of date. The only manuscript of the Lexicon is the Codex Galeanus, which passed into the library of Trinity College, Cambridge.

His most important theological work is the Amphilochia, a collection of some 300 questions and answers on difficult points in Scripture, addressed to Amphilochius, archbishop of Cyzicus. Other similar works are his treatise in four books against the Manichaeans and Paulicians, and his controversy with the Latins on the Procession of the Holy Spirit. Photios also addressed a long letter of theological advice to the newly-converted Boris I of Bulgaria. Numerous other Epistles also survive. The chief contemporary authority for the life of Photios is his bitter enemy, Niketas David Paphlagon, the biographer of his rival Ignatios.

The Bibliotheca or Myriobiblon was a 9th century work of Byzantine Patriarch Photius, dedicated to his brother and composed of 279 reviews of books which he had read. It was not meant to be used as a reference work, but was widely used as such in the 9th century, and is generally seen as the first Byzantine work that could be called an Encyclopedia. The works he notes are mainly Christian and pagan authors from the 5th century BC to his own time in the 9th century AD. Almost half the books mentioned no longer survive.

There has been discussions on whether the Bibliotheca was in fact compiled in Baghdad at the time of Photius' embassy to the Abbasid court in Samarra in june 845, since many of the mentioned works - the majority by secular authors - seems to have been virtually nonexistent in both contemporary and later Byzantium. The Abbasids showed great interest in translating classical Greek works to Arabic and Photius might have studied them during his years in exile in Baghdad. Editio princeps (in Greek): David Hoeschel, Augsburg, 1601. Modern critical edition by R. Henry.

Codex

178

Dioscorides

Read On

Matter by Dioscorides![]() , a

work divided in seven books 1

, a

work divided in seven books 1![]() . In

five of them he speaks about herbs, plants, aromatics, and the preparation of

oils and unguents. He also deals with animals and the use that may be made of

certain of their organs; of trees, the juices which come from them, or which

lose them, of honey and also of milk, of grass, of plants that are called

cereals or vegetables, of the roots of plants and of shrubs and herbs and of

the usage of their juice for medicine or nourishment. Further, he deals in a

fully sufficient manner with wines and metals and, for most of the items he

intends to discuss, he describes the appearance, the nature of these items,

and the places where they may be found in a very exact manner so that one can

recognise the object searched for; he speaks less of the usage that one can

make of them or he describes the search with less exactitude. He also gives

various ways to deal with wines in this part.

. In

five of them he speaks about herbs, plants, aromatics, and the preparation of

oils and unguents. He also deals with animals and the use that may be made of

certain of their organs; of trees, the juices which come from them, or which

lose them, of honey and also of milk, of grass, of plants that are called

cereals or vegetables, of the roots of plants and of shrubs and herbs and of

the usage of their juice for medicine or nourishment. Further, he deals in a

fully sufficient manner with wines and metals and, for most of the items he

intends to discuss, he describes the appearance, the nature of these items,

and the places where they may be found in a very exact manner so that one can

recognise the object searched for; he speaks less of the usage that one can

make of them or he describes the search with less exactitude. He also gives

various ways to deal with wines in this part.

In the sixth book, he discusses remedies: those which are harmful and those which attack illness. In the seventh, which is also the last of all his research, he undertakes an enquiry into animals that throw darts and on the means thanks to which those who have encountered these animals will find a relief and even a complete cure.

Such is the general purpose of the work. This book is useful not only for the practice of medicine, but also for speculations on philosophy and the natural sciences. Of all those since Dioscurides who have written about simples, some have merely copied his work, others have not even cared to transcribe it exactly, but have broken up the ensemble of teaching on each subject so as to group in one part the facts about appearance, nature and reproduction of simples, and in the other part to describe in detail their use and usefulness.

Alexander,

Paul

2![]() and

Aetius

3

and

Aetius

3![]() and

the other writers of the same kind have not even taken any account of the

appearance of plants, but have merely extracted the information relating to

their use to include in their own treatises; and further, Paul has left out

what Dioscurides said about the use of plants, but has collected a number of

facts on the use and usefulness of items which the latter did not

mention.Aetius has not only added nothing, but has left out, I do not know why,

much that Dioscurides wrote. And even Oribasos himself, who seems to be the

most lengthy of them, has not transcribed in its own groups all that

Dioscurides wrote, but has separated the use of the form and of the nature.

and

the other writers of the same kind have not even taken any account of the

appearance of plants, but have merely extracted the information relating to

their use to include in their own treatises; and further, Paul has left out

what Dioscurides said about the use of plants, but has collected a number of

facts on the use and usefulness of items which the latter did not

mention.Aetius has not only added nothing, but has left out, I do not know why,

much that Dioscurides wrote. And even Oribasos himself, who seems to be the

most lengthy of them, has not transcribed in its own groups all that

Dioscurides wrote, but has separated the use of the form and of the nature.

And Galen, apart from leaving out a very great number of facts on plants, has only transcribed the information on the powers and uses of the items of which he talks: he has only given a feeble justification of his omissions of form and nature.Although, in discussing herbs, he speaks of them with more detail than Dioscurides, exceeding the reputation of this writer in usefulness for this one part, which is not the least important, he surpasses him less all the same because he does not appear inferior to him in his treatise on plants. To my knowledge, for things that concern knowledge of appearance, nature and origin of these plants, no author can be found more useful than Dioscurides.

According

to the testimony of Galen, the author was from Anazarba. Myself I have found

in the subscriptio's [of manuscripts] that he is called at the same time from

Anazarba and from Peda 4![]() . Among

the many authors who have treated the same subject before him, he is revealed

as having the most exact and most useful usage of them all.

. Among

the many authors who have treated the same subject before him, he is revealed

as having the most exact and most useful usage of them all.

1. This work has survived in 5 books, while Photius knows of 7. It belongs to the 2nd century AD. The work was edited by Max Wellmann, Berlin: Weidmann (1906-14). See Wellmann, Dioskurides (n. 12), in P. W., vol. V (1905), col. 1131-1142. Dante placed Dioscurides in the first circle of Hell, that inhabited by the good pagans. Inferno IV 139-141: e vidi il buono accoglitor del quale, | Dioscoride dico; e vidi Orfeo, | Tullio e Lino e Seneca morale; [...].

2. An important 7th century AD compiler. Cf. Diller, s. v. Paulus (n. 23), in P. W., t. XVIII, 2 (1949), col. 2386-2387.

3.

Aetius of Amida![]() , a 6th

century AD writer. He was the author of a large compilation in 60 books (see

codex 221). The three authors mentions knew Dioscurides work only indirectly,

according to Wellmann.Cf. Wellmann, s. v. Aetios (n. 8), in P. W.,

t. I (1894), col. 703-704, et Supplementband I, col. 29

, a 6th

century AD writer. He was the author of a large compilation in 60 books (see

codex 221). The three authors mentions knew Dioscurides work only indirectly,

according to Wellmann.Cf. Wellmann, s. v. Aetios (n. 8), in P. W.,

t. I (1894), col. 703-704, et Supplementband I, col. 29

4. The manuscripts of his work call him [Greek]. This is without doubt the source of Photius' comment. Péda in Greek was Pedum in Latin, a city in ancient Latium near Gallicano nel Lazio of today, province of Rome.

Translated from modern critical edition of R. Henry

www.tertullian.org