Lessico

San

Girolamo

Eusebius Hieronymus

Dottore

della Chiesa latina (Stridone, Istria, ca. 347 - Betlemme, Palestina, 419 o

420). Studiò a Roma sotto la guida di Elio Donato![]() ,

approfondendo gran parte dello scibile di allora e ricevendo il battesimo.

Dopo un breve periodo a Treviri per trascrivere le opere di autori cristiani,

sentendo l'impulso verso la vita monastica si ritirò nel deserto della

Calcide presso Antiochia e si applicò allo studio dell'ebraico.

,

approfondendo gran parte dello scibile di allora e ricevendo il battesimo.

Dopo un breve periodo a Treviri per trascrivere le opere di autori cristiani,

sentendo l'impulso verso la vita monastica si ritirò nel deserto della

Calcide presso Antiochia e si applicò allo studio dell'ebraico.

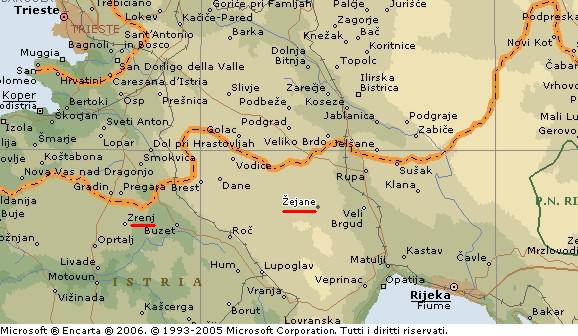

Incerto

il luogo di nascita del grande Girolamo. Chi lo colloca in Dalmazia, chi in

Istria. Tra coloro che lo collocano in Istria, c'è chi propende per Zrenj,

chi per i dintorni di Zejane che si trova 25 km a est di Zrenj. Ecco

quanto riferito da http://razor.arnes.si: "In quel periodo la chiesa di

Aquileia![]() raggiunse il massimo splendore, che si manifestava anche nella grande

fioritura della letteratura cristiana, cresciuta nella cerchia degli asceti

aquileiesi dopo il 370. La massima espressione di tale letteratura fu il

grande Gerolamo, nato nella località di Stridone, al confine tra l'Istria, la

Pannonia e la Dalmazia. Il toponimo Stridone corrisponde al nome medievale del

villaggio di Sdregna presso Pinguente, dove ha situato i natali del santo la

maggioranza degli storiografi italiani del passato. Però attorno al luogo di

nascita di questo famoso scrittore cristiano gli storici e gli scrittori

ecclesiastici hanno discusso parecchio, e ultimamente R. Bratoz, in un saggio

del suo libro Zgodovina Cerkve na Slovenskem (Storia della Chiesa in

Slovenia), pubblicato nel 1991, accetta la tesi più recente, a suo avviso

fondata, secondo cui la località si trovava nella zona della Ciceria tra

Starad, Sapgliane e Zejane."

raggiunse il massimo splendore, che si manifestava anche nella grande

fioritura della letteratura cristiana, cresciuta nella cerchia degli asceti

aquileiesi dopo il 370. La massima espressione di tale letteratura fu il

grande Gerolamo, nato nella località di Stridone, al confine tra l'Istria, la

Pannonia e la Dalmazia. Il toponimo Stridone corrisponde al nome medievale del

villaggio di Sdregna presso Pinguente, dove ha situato i natali del santo la

maggioranza degli storiografi italiani del passato. Però attorno al luogo di

nascita di questo famoso scrittore cristiano gli storici e gli scrittori

ecclesiastici hanno discusso parecchio, e ultimamente R. Bratoz, in un saggio

del suo libro Zgodovina Cerkve na Slovenskem (Storia della Chiesa in

Slovenia), pubblicato nel 1991, accetta la tesi più recente, a suo avviso

fondata, secondo cui la località si trovava nella zona della Ciceria tra

Starad, Sapgliane e Zejane."

Fu poi a Berea e a Costantinopoli, dove continuò lo studio delle Sacre Scritture. Nel 382 andò con San Paolino a Roma e fu segretario di papa Damaso, ma continuò la sua opera di divulgazione della vita monastica e si cimentò con i primi lavori biblici, curando la revisione della traduzione latina dei Vangeli.

Fatto

oggetto di calunnie alla morte di papa Damaso, si ritirò definitivamente a

Betlemme, dedicandosi alla costruzione di monasteri e alla corrispondenza con

gli ecclesiastici più illustri del suo tempo, fra cui Sant'Agostino![]() .

Festa il 30 settembre.

.

Festa il 30 settembre.

Girolamo è, tra i padri della Chiesa, quello più legato alla tradizione classica per spirito e cultura. Anzi, la letteratura profana e quella religiosa furono due diverse attrattive del suo animo inquieto e combattivo (celebre la sua disputa con Sant'Agostino a proposito delle versioni delle Sacre Scritture).

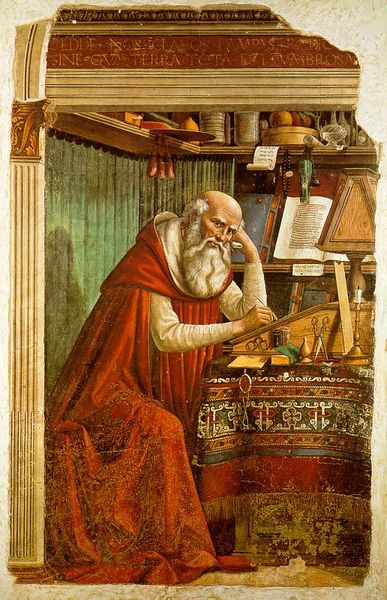

San

Girolamo nel suo studio

Domenico Bigordi detto il Ghirlandaio (Firenze 1449-1494)

Chiesa di Ognissanti - Firenze - 1480

Immensa

l'orma da lui lasciata negli studi cristiani, ma anche, per alcuni suoi

lavori, negli studi profani. Sue opere principali sono: la traduzione e

continuazione fino al 381 della Chronica di Eusebio di Cesarea![]() ,

testo tuttora fondamentale per stabilire la cronologia antica, anche

letteraria; De viris illustribus, composto da brevi biografie di 135

scrittori cristiani, compreso lo stesso Girolamo, e modellato sull'omonima

raccolta di Svetonio

,

testo tuttora fondamentale per stabilire la cronologia antica, anche

letteraria; De viris illustribus, composto da brevi biografie di 135

scrittori cristiani, compreso lo stesso Girolamo, e modellato sull'omonima

raccolta di Svetonio![]() ;

varie Vite di monaci, assai belle per il tono favoloso e la delicata

poesia che le pervade; la revisione delle antiche versioni latine del Nuovo

Testamento e la traduzione di tutto l'Antico Testamento dall'ebraico in latino

(l'edizione Vulgata

;

varie Vite di monaci, assai belle per il tono favoloso e la delicata

poesia che le pervade; la revisione delle antiche versioni latine del Nuovo

Testamento e la traduzione di tutto l'Antico Testamento dall'ebraico in latino

(l'edizione Vulgata![]() delle Sacre Scritture, dichiarata “autentica”

dal Concilio di Trento e adottata ufficialmente dalla Chiesa); numerosissime

opere esegetiche sui libri dei Profeti, sui Salmi, sul Vangelo di Matteo, su 4

lettere di San Paolo; altre opere di violentissima polemica contro gli

avversari (Adversus Helvidium, Adversus Iovinianum, Contra

Vigilantium, Contra Ioannem, Apologia adversus Rufinum, Contra Pelagianos);

omelie e un epistolario di 150 interessantissime lettere, in cui si riflettono

il carattere impetuoso ma anche generoso del santo e gli avvenimenti

drammatici di quegli anni, come il sacco di Roma da parte di Alarico, nel 410.

delle Sacre Scritture, dichiarata “autentica”

dal Concilio di Trento e adottata ufficialmente dalla Chiesa); numerosissime

opere esegetiche sui libri dei Profeti, sui Salmi, sul Vangelo di Matteo, su 4

lettere di San Paolo; altre opere di violentissima polemica contro gli

avversari (Adversus Helvidium, Adversus Iovinianum, Contra

Vigilantium, Contra Ioannem, Apologia adversus Rufinum, Contra Pelagianos);

omelie e un epistolario di 150 interessantissime lettere, in cui si riflettono

il carattere impetuoso ma anche generoso del santo e gli avvenimenti

drammatici di quegli anni, come il sacco di Roma da parte di Alarico, nel 410.

Lo stile di Girolamo è di grande eleganza e ispirato a quello che egli riconosceva come il proprio modello: Cicerone; Girolamo fu anzi detto il “Cicerone cristiano”.

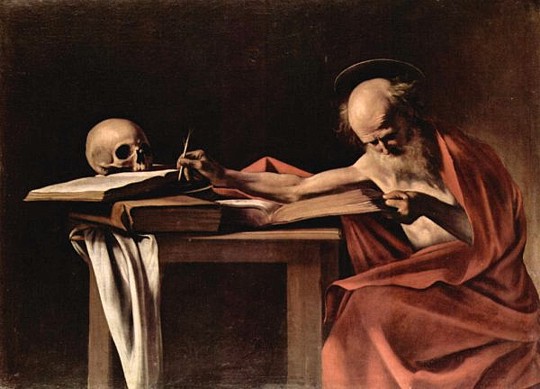

Sofronio Eusebio Girolamo

San

Girolamo – 1605/1606

di Michelangelo Merisi detto il Caravaggio (1571-1610)

Sofronio Eusebio Girolamo, noto come san Girolamo o san Geronimo (Stridone in Dalmazia 347 – Betlemme, settembre 420), è venerato come santo nonché padre e dottore della Chiesa dalla Chiesa cattolica. Fu il primo traduttore della Bibbia dal greco e dall'ebraico al latino. Studiò a Roma sotto la guida di Elio Donato; nel 379, ordinato prete dal vescovo Paolino di Nola, si recò a Costantinopoli dove poté perfezionare lo studio del greco sotto la guida di Gregorio Nazianzeno (uno dei "Padri Cappadoci"). Risalgono a questo periodo le letture dei testi di Origene e di Eusebio.

Dopo tre anni di vita monastica tornò a Roma, nel 382, dove divenne segretario di papa Damaso I e conseguì un notevole successo personale, ma alla morte del Papa il suo prestigio scemò e Girolamo tornò in Oriente, dove fondò alcuni conventi femminili e maschili, in uno dei quali trascorse gli ultimi anni. Morì nel 420.

La Vulgata

La Vulgata, prima traduzione completa in lingua latina della Bibbia, rappresenta lo sforzo più impegnativo affrontato da Girolamo. Nel 382 su incarico di papa Damaso I affrontò il compito di rivedere la traduzione dei Vangeli, successivamente, nel 390, passò all'Antico Testamento in ebraico concludendo l'opera dopo ben 23 anni.

Il testo di Girolamo è stato la base per molte delle successive traduzioni della Bibbia, fino al XX secolo quando per l'Antico Testamento si è cominciato a utilizzare direttamente il testo masoretico ebraico e la Septuaginta, mentre per il nuovo testamento si sono utilizzati direttamente i testi greci.

Girolamo fu un celebre studioso del latino in un'epoca in cui questo implicava una perfetta conoscenza del greco. Fu battezzato all'età di 25 anni e divenne sacerdote a 38. Quando cominciò la sua opera di traduzione non aveva una perfetta conoscenza dell'ebraico, perciò si trasferì a Betlemme per perfezionarne la conoscenza. Girolamo utilizzò un concetto moderno di traduzione che attirò le accuse da parte dei suoi contemporanei. In una lettera indirizzata a Pammachio, genero della nobildonna romana Paola, scrisse:

« Io, infatti, non solo ammetto, ma proclamo liberamente che nel tradurre i testi greci, a parte le Sacre Scritture, dove anche l’ordine delle parole è un mistero, non rendo la parola con la parola, ma il senso con il senso. Ho come maestro di questo procedimento Cicerone, che tradusse il Protagora di Platone, l’Economico di Senofonte e le due bellissime orazioni che Eschine e Demostene scrissero l’uno contro l’altro [...]. Anche Orazio poi, uomo acuto e dotto, nell’Ars poetica dà questi stessi precetti al traduttore colto: "Non ti curerai di rendere parola per parola, come un traduttore fedele" » (Epistulae 57, 5, trad. R. Palla)

Adversus Jovinianum

Nel trattato Adversus Jovinianum, scritto nel 393 in due libri, l'autore esalta la verginità e l'ascetismo, spesso derivando le sue argomentazioni da autori classici come Teofrasto, Seneca, Porfirio. Tra gli altri argomenti, in esso Girolamo difende strenuamente l'astinenza dalla carne dimostrandosi un vegetariano ante litteram:

« Fino al diluvio non si conosceva il piacere dei pasti a base di carne ma dopo questo evento ci è stata riempita la bocca di fibre e di secrezioni maleodoranti della carne degli animali [...] Gesù Cristo, che venne quando fu compiuto il tempo, ha collegato la fine con l’inizio. Pertanto ora non ci è più consentito di mangiare la carne degli animali. » (Adversus Jovinanum, I, 30)

De viris illustribus

Il De Viris Illustribus, scritto nel 392, intendeva emulare le Vite svetoniane dimostrando come la nuova letteratura cristiana fosse in grado di porsi sullo stesso piano delle opere classiche. In esso sono presentate le biografie di 135 autori in prevalenza cristiani (ortodossi ed eterodossi), ma anche ebrei e pagani, che però hanno avuto a che fare con il cristianesimo, con uno scopo dichiaratamente apologetico:

« Sappiano Celso, Porfirio, Giuliano, questi cani arrabbiati contro Cristo, così come i loro seguaci che pensano che la Chiesa non ha mai avuto oratori, filosofi e colti dottori, sappiano quali uomini di valore l’hanno fondata, edificata, illustrata, e cessino le loro accuse sommarie di semplicità rozza rivolte alla nostra fede, e riconoscano piuttosto la loro ignoranza » (Prologo, 14)

Le biografie hanno inizio da san Pietro e terminano allo stesso Girolamo ma, mentre nelle successive Girolamo elabora conoscenze personali, le prime 78 sono frutto di conoscenze di seconda mano non sempre completamente affidabili, tra cui Eusebio di Cesarea. L’opera venne talora indicata da Girolamo stesso col titolo De scriptoribus ecclesiasticis.

Il culto

Il Martirologio romano ricorda San Girolamo il 30 settembre. Per la sua attività di traduttore della Bibbia viene considerato santo protettore dei traduttori e per i suoi studi legati all'antichità è considerato il patrono degli archeologi. Nell'iconografia è spesso rappresentato come un vecchio dalla barba bianca intento a scrivere. I simboli nelle opere artistiche sono: il libro (la Vulgata), il leone fido compagno nel deserto al quale aveva tolto una spina, il cappello cardinalizio ottenuto a Roma quando era consigliere dal Papa Damaso I, il Crocifisso e il teschio, segno di penitenza cristiana. Viene anche rappresentato penitente nella grotta di Betlemme, dove si era ritirato sia per vivere la sua vocazione da eremita sia per attendere alla traduzione della Bibbia.

Curiosità

In una lettera all’amico Paolino da Nola, Girolamo si lamenta dei "dilettanti" che si arrogano il diritto di emettere sentenze sulla Bibbia: « Agricolae, caementarii, fabri, metallorum lignorum que caesores, lanarii quoque et fullones et ceteri, qui variam supellectilem et vilia opuscula fabricantur, absque doctore non possunt esse, quod cupiunt. Sola scripturarum ars est, quam sibi omnes passim vindicent: scribimus indocti docti que poemata passim. Hanc garrula anus, hanc delirus senex, hanc soloecista verbosus, hanc universi praesumunt, lacerant, docent, antequam discant [...] et, ne parum hoc sit, quadam facilitate verborum, immo audacia disserunt aliis, quod ipsi non intellegunt. Taceo de meis similibus, qui si forte ad scripturas sanctas post saeculares litteras venerint [...] sed ad sensum suum incongrua aptant testimonia, quasi grande sit et non vitiosissimum dicendi genus depravare sententias et ad voluntatem suam scripturam trahere repugnantem [...] Puerilia sunt haec et circulatorum ludo similia, docere, quod ignores, immo, et cum clitomacho loquar, nec hoc quidem scire, quod nescias. » (Epistula LIII ad Paulinum presbyterum, 7)

Saint

Jerome – 1625/1630

by Pieter Paul Rubens (1577-1640)

Saint Jerome (c. 347 – September 30, 420) (Latin: Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus) was a Christian priest and Christian apologist best known for translating the Vulgate. He is recognized by the Catholic Church as a canonized saint and Doctor of the Church, and his version of the Bible is still an important text in Catholicism. He is also recognized as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church, where he is known as St Jerome of Stridonium or Blessed Jerome. He is presumed by some to have been an Illyrian, but this may just be conjecture.

In the Catholic Church, it has been usual to represent him (the patron of theological learning) anachronistically, as a cardinal, by the side of Augustine of Hippo, Ambrose, and Pope Gregory I. Even when he is depicted as a half-clad anchorite, with cross, skull and Bible for the only furniture of his cell, the red hat or some other indication of his rank as cardinal is as a rule introduced somewhere in the picture. He is also often depicted with a lion, due to a medieval story in which he removed a thorn from a lion's paw, and less often with an owl, the symbol of wisdom and scholarship. Writing materials and the trumpet of final judgment are also part of his iconography. He is commemorated on 30 September with a memorial.

Life

Jerome was born at Stridon, on the border between Pannonia and Dalmatia, close to Aquileia, as mentioned in his De Viris Illustribus Chapter 135 (English translation below). Jerome was possibly an Illyrian, born to Christian parents, but was not baptized until about 360 or 366, when he had gone to Rome with his friend Bonosus (who may or may not have been the same Bonosus whom Jerome identifies as his friend who went to live as a hermit on an island in the Adriatic) to pursue rhetorical and philosophical studies. He studied under the grammarian Aelius Donatus. Jerome learned Greek, but yet had no thought of studying the Greek Fathers, or any Christian writings.

Payne offers a different account of his conversion. As a student in Rome, he engaged in the gay activities of students there which he indulged in quite casually yet suffered terrible bouts of repentance afterwards. To appease his conscience, he would visit on Sundays the sepulchres of the martyrs and the apostles in the catacombs. This experience would remind him of the terrors of hell. "Often I would find myself entering those crypts, deep dug in the earth, with their walls on either side lined with the bodies of the dead, where everything was so dark that almost it seemed as though the Psalmist’s words were fulfilled, Let them go down quick into Hell. Here and there the light, not entering in through windows, but filtering down from above through shafts, relieved the horror of the darkness. But again, as soon as you found yourself cautiously moving forward, the black night closed around and there came to my mind the line of Vergil, Horror ubique animo, simul ipsa silentia terrent." (Jerome, Commentarius in Ezechielem, c. 40, v. 5)

Jerome initially used classical authors to describe Christian concepts, such as hell, that indicated both his classical education and his deep shame of their associated practices, such as male homosexuality. Although initially skeptical of Christianity, he finally converted. After several years in Rome, he travelled with Bonosus to Gaul and settled in Trier "on the semi-barbarous banks of the Rhine" where he seems to have first taken up theological studies, and where he copied, for his friend Rufinus, Hilary of Poitiers' commentary on the Psalms and the treatise De synodis. Next came a stay of at least several months, or possibly years, with Rufinus at Aquileia where he made many Christian friends.

Some of these accompanied him when he set out about 373 on a journey through Thrace and Asia Minor into northern Syria. At Antioch, where he stayed the longest, two of his companions died and he himself was seriously ill more than once. During one of these illnesses (about the winter of 373-374), he had a vision that led him to lay aside his secular studies and devote himself to the things of God. He seems to have abstained for a considerable time from the study of the classics and to have plunged deeply into that of the Bible, under the impulse of Apollinaris of Laodicea, then teaching in Antioch and not yet suspected of heresy.

Seized with a desire for a life of ascetic penance, he went for a time to the desert of Chalcis, to the southwest of Antioch, known as the Syrian Thebaid, from the number of hermits inhabiting it. During this period, he seems to have found time for study and writing. He made his first attempt to learn Hebrew under the guidance of a converted Jew; and he seems to have been in correspondence with Jewish Christians in Antioch, and perhaps as early as this to have interested himself in the Gospel of the Hebrews, said by them to be the source of the canonical Matthew.

Returning to Antioch in 378 or 379, he was ordained by Bishop Paulinus, apparently unwillingly and on condition that he continue his ascetic life. Soon afterward, he went to Constantinople to pursue a study of Scripture under Gregory Nazianzen. He seems to have spent two years there; the next three (382-385) he was in Rome again, attached to Pope Damasus I and the leading Roman Christians. Invited originally for the synod of 382, held to end the schism of Antioch, he made himself indispensable to the pope, and took a prominent place in his councils.

Among his other duties, he undertook a revision of the Latin Bible, to be based on the Greek New Testament. He also updated the Psalter then at use in Rome based on the Septuagint. Though he did not realize it yet at this point, translating much of what became the Latin Vulgate Bible would take many years, and be his most important achievement (see Writings - Translations section below).

In Rome he was surrounded by a circle of well-born and well-educated women, including some from the noblest patrician families, such as the widows Marcella and Paula, with their daughters Blaesilla and Eustochium. The resulting inclination of these women to the monastic life, and his unsparing criticism of the secular clergy, brought a growing hostility against him amongst the clergy and their supporters. Soon after the death of his patron Damasus (December 10, 384), Jerome was forced to leave his position at Rome after an inquiry by the Roman clergy into allegations that he had improper relations with the widow Paula.

In August 385, he returned to Antioch, accompanied by his brother Paulinianus and several friends, and followed a little later by Paula and Eustochium, who had resolved to end their days in the Holy Land. In the winter of 385, Jerome acted as their spiritual adviser. The pilgrims, joined by Bishop Paulinus of Antioch, visited Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and the holy places of Galilee, and then went to Egypt, the home of the great heroes of the ascetic life. At the Catechetical School of Alexandria, Jerome listened to the blind catechist Didymus the Blind expounding the prophet Hosea and telling his reminiscences of Anthony the Great, who had died thirty years before; he spent some time in Nitria, admiring the disciplined community life of the numerous inhabitants of that "city of the Lord", but detecting even there "concealed serpents", i.e., the influence of Origen of Alexandria. Late in the summer of 388 he was back in Palestine, and spent the remainder of his life in a hermit's cell near Bethlehem, surrounded by a few friends, both men and women (including Paula and Eustochium), to whom he acted as priestly guide and teacher.

Amply provided by Paula with the means of livelihood and of increasing his collection of books, he led a life of incessant activity in literary production. To these last thirty-four years of his career belong the most important of his works -- his version of the Old Testament from the original Hebrew text, the best of his scriptural commentaries, his catalogue of Christian authors, and the dialogue against the Pelagians, the literary perfection of which even an opponent recognized. To this period also belong most of his polemics, which distinguished him among the orthodox Fathers, including the treatises against the Origenism of Bishop John II of Jerusalem and his early friend Rufinus. As a result of his writings against Pelagianism, a body of excited partisans broke into the monastic buildings, set them on fire, attacked the inmates and killed a deacon, forcing Jerome to seek safety in a neighboring fortress (416).

Jerome died near Bethlehem on September 30, 420. The date of his death is given by the Chronicon of Prosper of Aquitaine. His remains, originally buried at Bethlehem, are said to have been later transferred to the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, though other places in the West claim some relics -- the cathedral at Nepi boasting possession of his head, which, according to another tradition, is in the Escorial.

Translations and commentaries

Jerome was a scholar at a time when that statement implied a fluency in Greek. He knew some Hebrew when he started his translation project, but moved to Jerusalem to strengthen his grip on Jewish scripture commentary. A wealthy Roman aristocrat, Paula, funded his stay in a monastery in Bethlehem and he completed his translation there. He began in 382 by correcting the existing Latin language version of the New Testament, commonly referred to as the Vetus Latina. By 390 he turned to the Hebrew Bible, having previously translated portions from the Septuagint. He completed this work by 405. Prior to Jerome's Vulgate, all Latin translations of the Old Testament were based on the Septuagint. Jerome's decision to use the Masoretic Text instead of the Septuagint went against the advice of most other Christians, including Augustine, who considered the Septuagint inspired. Modern scholarship, however, has cast doubts on the actual quality of Jerome's Hebrew knowledge; the Greek Hexapla is now considered as still the main source also for Jerome's "iuxta Hebraeos" translation of the Old Testament.

For the next fifteen years, until he died, Jerome produced a number of commentaries on Scripture, often explaining his translation choices. His patristic commentaries align closely with Jewish tradition, and he indulges in allegorical and mystical subtleties after the manner of Philo and the Alexandrian school. Unlike his contemporaries, he emphasizes the difference between the Hebrew Bible "apocrypha" and the Hebraica veritas of the protocanonical books. Evidence of this can be found in his introductions to the Solomonic writings, the Book of Tobit, and the Book of Judith. Most notable, however, is the statement from his introduction to the Books of Samuel: This preface to the Scriptures may serve as a helmeted [i.e. defensive] introduction to all the books which we turn from Hebrew into Latin, so that we may be assured that what is outside of them must be placed aside among the Apocryphal writings. Jerome's commentaries fall into three groups:

His translations or recastings of Greek predecessors, including fourteen homilies on the Book of Jeremiah and the same number on the Book of Ezekiel by Origen (translated ca. 380 in Constantinople); two homilies of Origen of Alexandria on the Song of Solomon (in Rome, ca. 383); and thirty-nine on the Gospel of Luke (ca. 389, in Bethlehem). The nine homilies of Origen on the Book of Isaiah included among his works were not done by him. Here should be mentioned, as an important contribution to the topography of Palestine, his book De situ et nominibus locorum Hebraeorum, a translation with additions and some regrettable omissions of the Onomasticon of Eusebius. To the same period (ca. 390) belongs the Liber interpretationis nominum Hebraicorum, based on a work supposed to go back to Philo and expanded by Origen.

Original commentaries on the Old Testament. To the period before his settlement at Bethlehem and the following five years belong a series of short Old Testament studies: De seraphim, De voce Osanna, De tribus quaestionibus veteris legis (usually included among the letters as 18, 20, and 36); Quaestiones hebraicae in Genesin; Commentarius in Ecclesiasten; Tractatus septem in Psalmos 10-16 (lost); Explanationes in Michaeam, Sophoniam, Nahum, Habacuc, Aggaeum. About 395 he composed a series of longer commentaries, though in rather a desultory fashion: first on the remaining seven minor prophets, then on Isaiah (ca. 395-ca. 400), on the Book of Daniel (ca. 407), on Ezekiel (between 410 and 415), and on Jeremiah (after 415, left unfinished).

New Testament commentaries. These include only Philemon, Galatians, Ephesians, and Titus (hastily composed 387-388); Matthew (dictated in a fortnight, 398); Mark, selected passages in Luke, Revelation, and the prologue to the Gospel of John. Treating Revelation in his cursory fashion, he made use of an excerpt from the commentary of the North African Tichonius, which is preserved as a sort of argument at the beginning of the more extended work of the Spanish presbyter Beatus of Liébana. But before this he had already devoted to the Revelation another treatment, a rather arbitrary recasting of the commentary of Saint Victorinus, with whose chiliastic views he was not in accord, substituting for the chiliastic conclusion a spiritualizing exposition of his own, supplying an introduction, and making certain changes in the text.

The works of Hippolytus of Rome and Irenaeus greatly influenced Jerome's interpretation of prophecy. He noted the distinction between the original Septuagint and Theodotion's later substitution. His Commentary on Daniel was expressly written to offset the criticisms of Porphyry, who taught that Daniel related entirely to the time of Antiochus IV Epiphanes and was written by an unknown individual living in the second century BC. Against Porphyry, Jerome identified Rome as the fourth kingdom of chapters two and seven, but his view of chapters eight and 11 was more complex. Jerome held that chapter eight describes the activity of Antiochus Epiphanes, who is understood as a "type" of a future antichrist; 11:24 onwards applies primarily to a future antichrist but was partially fulfilled by Antiochus.

Jerome identified the four prophetic kingdoms symbolized in Daniel 2 as the Neo-Babylonian Empire, the Medes and Persians, Macedon, and Rome. Jerome identified the stone cut out without hands as "namely, the Lord and Savior". Jerome refuted Porphyry's application of the little horn of chapter seven to Antiochus. He expected that at the end of the world, Rome would be destroyed, and partitioned among ten kingdoms before the little horn appeared. Jerome believed that Cyrus of Persia is the higher of the two horns of the Medo-Persian ram of Daniel 8:3. The he-goat is Greece smiting Persia. Alexander is the great horn, which is then succeeded by Alexander's half brother Philip and three of his generals.

Historical writings

One of Jerome's earliest attempts in the department of history was his Chronicle (or Chronicon or Temporum liber), composed ca. 380 in Constantinople; this is a translation into Latin of the chronological tables which compose the second part of the Chronicon of Eusebius, with a supplement covering the period from 325 to 379. Despite numerous errors taken over from Eusebius, and some of his own, Jerome produced a valuable work, if only for the impulse which it gave to such later chroniclers as Prosper, Cassiodorus, and Victor of Tunnuna to continue his annals. Three other works of a hagiological nature are:

the Vita Pauli monachi,

written during his first sojourn at Antioch (ca. 376), the legendary material

of which is derived from Egyptian monastic tradition;

the Vita Malchi monachi captivi (ca. 391), probably based on an earlier

work, although it purports to be derived from the oral communications of the

aged ascetic Malchus originally made to him in the desert of Chalcis;

the Vita Hilarionis, of the same date, containing more trustworthy historical matter than the other two, and based partly on the biography of Epiphanius and partly on oral tradition.

The so-called Martyrologium Hieronymianum is spurious; it was apparently composed by a western monk toward the end of the sixth or beginning of the seventh century, with reference to an expression of Jerome's in the opening chapter of the Vita Malchi, where he speaks of intending to write a history of the saints and martyrs from the apostolic times.

But the most important of Jerome's historical works is the book De viris illustribus, written at Bethlehem in 392, the title and arrangement of which are borrowed from Suetonius. It contains short biographical and literary notes on 135 Christian authors, from Saint Peter down to Jerome himself. For the first seventy-eight authors Eusebius (Historia ecclesiastica) is the main source; in the second section, beginning with Arnobius and Lactantius, he includes a good deal of independent information, especially as to western writers.

Letters

Jerome's letters or epistles, both by the great variety of their subjects and by their qualities of style, form the most interesting portion of his literary remains. Whether he is discussing problems of scholarship, or reasoning on cases of conscience, comforting the afflicted, or saying pleasant things to his friends, scourging the vices and corruptions of the time, exhorting to the ascetic life and renunciation of the world, or breaking a lance with his theological opponents, he gives a vivid picture not only of his own mind, but of the age and its peculiar characteristics.

The letters most frequently reprinted or referred to are of a hortatory nature, such as Ep. 14, Ad Heliodorum de laude vitae solitariae; Ep. 22, Ad Eustochium de custodia virginitatis; Ep. 52, Ad Nepotianum de vita clericorum et monachorum, a sort of epitome of pastoral theology from the ascetic standpoint; Ep. 53, Ad Paulinum de studio scripturarum; Ep. 57, to the same, De institutione monachi; Ep. 70, Ad Magnum de scriptoribus ecclesiasticis; and Ep. 107, Ad Laetam de institutione filiae.

Theological writings

Practically all of Jerome's productions in the field of dogma have a more or less vehemently polemical character, and are directed against assailants of the orthodox doctrines. Even the translation of the treatise of Didymus the Blind on the Holy Spirit into Latin (begun in Rome 384, completed at Bethlehem) shows an apologetic tendency against the Arians and Pneumatomachoi. The same is true of his version of Origen's De principiis (ca. 399), intended to supersede the inaccurate translation by Rufinus. The more strictly polemical writings cover every period of his life. During the sojourns at Antioch and Constantinople he was mainly occupied with the Arian controversy, and especially with the schisms centering around Meletius of Antioch and Lucifer Calaritanus. Two letters to Pope Damasus (15 and 16) complain of the conduct of both parties at Antioch, the Meletians and Paulinians, who had tried to draw him into their controversy over the application of the terms ousia and hypostasis to the Trinity. At the same time or a little later (379) he composed his Liber Contra Luciferianos, in which he cleverly uses the dialogue form to combat the tenets of that faction, particularly their rejection of baptism by heretics.

In Rome (ca. 383) he wrote a passionate counterblast against the teaching of Helvidius, in defense of the doctrine of The perpetual virginity of Mary and of the superiority of the single over the married state. An opponent of a somewhat similar nature was Jovinianus, with whom he came into conflict in 392 (Adversus Jovinianum, Against Jovinianus) and the defense of this work addressed to his friend Pammachius, numbered 48 in the letters). Once more he defended the ordinary Catholic practices of piety and his own ascetic ethics in 406 against the Spanish presbyter Vigilantius, who opposed the cultus of martyrs and relics, the vow of poverty, and clerical celibacy. Meanwhile the controversy with John II of Jerusalem and Rufinus concerning the orthodoxy of Origen occurred. To this period belong some of his most passionate and most comprehensive polemical works: the Contra Joannem Hierosolymitanum (398 or 399); the two closely-connected Apologiae contra Rufinum (402); and the "last word" written a few months later, the Liber tertius seu ultima responsio adversus scripta Rufini. The last of his polemical works is the skilfully-composed Dialogus contra Pelagianos (415).

Jerome's reception by later Christianity

Jerome is the second most voluminous writer (after St. Augustine) in ancient Latin Christianity. In the Roman Catholic Church, he is recognized as the patron saint of translators, librarians and encyclopedists. He acquired a knowledge of Hebrew by studying with a Jew who converted to Christianity, and took the unusual position (for that time) that the Hebrew, and not the Septuagint, was the inspired text of the Old Testament. He used this knowledge to translate what became known as the Vulgate, and his translation was slowly but eventually accepted in the Catholic church. Obviously, the later resurgence of Hebrew studies within Christianity owes much to him.

Jerome sometimes seemed arrogant, and occasionally despised or belittled his literary rivals, especially Ambrose. It is not so much by absolute knowledge that he shines, as by a certain poetical elegance, an incisive wit, a singular skill in adapting recognized or proverbial phrases to his purpose, and a successful aiming at rhetorical effect. He showed more zeal and interest in the ascetic ideal than in abstract speculation. It was this strict asceticism that made Martin Luther judge him so severely. In fact, Protestant readers are not generally inclined to accept his writings as authoritative. The tendency to recognize a superior comes out in his correspondence with Augustine (cf. Jerome's letters numbered 56, 67, 102-105, 110-112, 115-116; and 28, 39, 40, 67-68, 71-75, 81-82 in Augustine's).

Despite the criticisms already mentioned, Jerome has retained a rank among the western Fathers. This would be his due, if for nothing else, on account of the great influence exercised by his Latin version of the Bible upon the subsequent ecclesiastical and theological development.

Jérôme de Stridon, en latin Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus Stridonensis (vers 340 - 30 septembre 420) est surtout connu pour ses traductions en latin de la Bible à partir du grec et de l'hébreu (la Vulgate). Les catholiques romains le considèrent comme un des Pères de l'Église et, avec les orthodoxes, le vénèrent comme saint. Depuis Boniface VIII, en 1298, il est qualifié de docteur de l'Église.

Résumé

Père de l'Église latine, né vers 340 ou 331, à Stridon, à la frontière entre la Pannonie et la Dalmatie (actuelle Croatie), il est mort à Bethléem le 30 septembre 420. Une tradition a fait de lui le patron des traducteurs. Jérôme de Stridon fait des études à Rome, se convertit à l'âge de 25 ans suite à un rêve mystérieux lors d'une maladie, puis, après un séjour en Gaule, part pour la Terre Sainte en 373 où il vit en ermite à Chalcis de Syrie dans la « Thébaïde de Syrie », au sud-ouest d'Antioche. Il est ensuite fait prêtre à Antioche (Asie Mineure). En 383, le pape Damase Ier le choisit comme secrétaire et lui demande de traduire la Bible en latin. À la mort du pape, il doit quitter Rome et retourne en Terre Sainte en compagnie de Paula, noble romaine. Ils fondent un monastère à Bethléem où il meurt en 419, à 91 ans. Durant les 34 dernières années de sa vie, Jérôme se consacre à l'écriture de l'Ancien Testament en latin à partir de sa propre traduction de l'hébreu et à rédiger ses commentaires sur la Bible. Ses restes sont d'abord enterrés à Jérusalem puis transférés à la Basilique Sainte-Marie-Majeure, une des quatre grandes basiliques de Rome. Sa traduction constitue la pièce maîtresse de la Vulgate, traduction de la Bible officiellement reconnue par l'Église catholique.

Biographie détaillée

Jérôme, bien que né de parents chrétiens, ne fut pas baptisé avant 360, date à laquelle il partit à Rome avec son frère Bonosus pour continuer ses études de rhétorique et de philosophie. Il étudia sous la férule d'Aelius Donat, un excellent grammairien. Jérôme apprit aussi le grec, sans avoir encore l'intention d'étudier les textes fondateurs du christianisme. Après quelques années à Rome, il se rendit avec Bonosus en Gaule, et s'installa à Trèves « sur la rive à moitié barbare du Rhin ». C'est là qu'il entama son parcours théologique et copia, pour son ami Rufin, le commentaire d'Hilaire de Poitiers sur les Psaumes, et le traité De synodis. Il séjourna ensuite pendant quelque temps (plusieurs années?) avec Rufin à Aquilée. Quelques-uns de ses amis chrétiens l'accompagnèrent lorsqu'il entama, vers 373, un voyage à travers la Thrace et l'Asie Mineure pour se rendre au nord de la Syrie. À Antioche, deux de ses compagnons moururent, et lui-même tomba malade plusieurs fois. Au cours de l'une de ces maladies (hiver 373-374) il fit un rêve qui le détourna des études profanes et l'engagea à se consacrer à Dieu. Dans ce rêve, qu'il raconte dans une de ses lettres, il lui fut reproché d'être « Cicéronien, et non pas chrétien ». Il semble avoir renoncé pendant une longue durée après ce rêve à l'étude des classiques profanes, et s'être plongé dans celle de la Bible sous l'impulsion d'Apollinaire de Laodicée. Il enseigna ensuite à Antioche. Désirant vivement vivre en ascète et faire pénitence, il passa quelque temps dans le désert de Chalcis de Syrie, au sud-ouest d'Antioche, connue sous le nom de « Thébaïde de Syrie », en raison du grand nombre d'ermites qui y vivaient. C'est à cette époque qu'il commença à apprendre l'hébreu avec l'aide d'un juif converti. Il fut en relation à cette époque avec les Chrétiens d'Antioche, et semble avoir commencé alors à s'intéresser à l'Évangile des Hébreux, qui était, selon les gens d'Antioche, la source de l'Évangile selon Matthieu.

À son retour à Antioche, en 378 ou 379, il fut ordonné par l'évêque Paulin. Peu de temps après, il partit à Constantinople pour continuer ses études de l'Écriture sous l'égide de Grégoire de Nazianze. Il passa deux ans là-bas, puis revint à Rome pendant trois ans (382-385), en contact direct avec le pape Damase et la tête de l'Église de Rome. Invité au concile de 382, qui était convoqué pour mettre fin au schisme d'Antioche, il sut se rendre indispensable au pape. Entre autres tâches, il prit en charge la révision du texte de la Bible Latine, sur la base du Nouveau Testament grec et du texte de la Septante, pour mettre fin aux divergences des textes qui circulaient en occident (connus sous le nom de Vetus Latina). Ce travail l'occupa pendant de très nombreuses années, et constitue son œuvre majeure. Il exerça une influence non négligeable au cours de ces trois années passées à Rome, notamment par son zèle à prôner l'ascétisme. Il s'entoura d'un cercle de femmes de la noblesse, dont certaines étaient issues des plus anciennes familles patriciennes, comme les veuves Marcella et Paula, et leurs filles Blaesilla et Eustochium (destinataire de la lettre la plus fameuse de Jérôme de Stridon, la 22e dans sa Correspondance). L'inclination de ces femmes à la vie monastique, et la critique virulente que faisait Jérôme du clergé régulier, firent naître une hostilité croissante à son égard de la part du clergé et de ses partisans. Peu de temps après la mort de son protecteur Damase (10 décembre 384), Jérôme quitta Rome.

En août 385, il retourna à Antioche, accompagné par son frère Paulinianus et quelques amis. Il fut suivi peu de temps après par Paula et Eustochium, résolues à quitter leur entourage patricien pour finir leurs jours sur la Terre Sainte. Au cours de l'hiver 385, Jérôme les accompagna. Les pèlerins, rejoints par l'évêque Paulin d'Antioche, visitèrent Jérusalem, Bethléem et les lieux saints de Galilée, puis partirent en Égypte, où vivaient les grands modèles de la vie ascétique. En Alexandrie, Jérôme put rencontrer et écouter le catéchiste Didyme l'Aveugle expliquer le prophète Osée et raconter les souvenirs qu'il avait de l'ascète Antoine, mort trente ans plus tôt. Il resta quelque temps à Nitrie à admirer la vie communautaire des nombreux habitants de cette « cité du Seigneur »; mais il ne fut pas sans critiquer le « serpent » qu'il voyait en Origène. À la fin de l'été 388, il revint en Palestine, et s'installa jusqu'à la fin de ses jours dans une cellule près de Bethléem, entouré par quelques amis, hommes et femmes.

Vivant grâce aux moyens que lui fournissait Paula, et accroissant sans cesse le nombre de ses livres, il écrivit sans cesse. On doit à ces trente-quatre dernières années de son existence la majeure partie de son œuvre: sa version de l'Ancien Testament à partir du texte hébreu, ses meilleurs commentaires sur l'Écriture, son catalogue des auteurs chrétiens, ainsi que le dialogue contre les Pélagiens. De cette période date également la majeure partie de ses textes polémiques, et notamment les traités dus à la controverse sur Origène avec l'évêque Jean d'Alexandrie. Suite à ses écrits contre les Pélagiens, une troupe de partisans de ces derniers envahit sa retraite, y mit le feu et contraignit Jérôme à se réfugier dans une forteresse avoisinante. La date de sa mort nous est connue par la chronique de Prosper d'Aquitaine. Ses restes, enterrés d'abord à Jérusalem, ont été ensuite transférés, dit-on, à l'église Sainte-Marie Majeure de Rome.

Traductions

Jérôme était un érudit de langue latine à une époque où cela impliquait de parler couramment le grec. Il savait un peu d'hébreu à l'époque où il commença son projet de traduction, mais il se rendit à Bethléem pour parfaire sa connaissance de la langue et améliorer son approche de la technique juive du commentaire scripturaire. Une aristocrate romaine aisée, Paula, fit construire un monastère pour lui à Bethléem, où il commença son travail de traduction. Il commença en 382 par la modification de la version latine du Nouveau Testament qui circulait à l'époque, connue sous le nom de Vetus Latina. Dans les années 390, il se tourna vers l'Ancien Testament, et le traduisit de l'hébreu, en connaissant en parallèle la version grecque des Septante. Il vint à bout de cette entreprise vers 405.

Au cours des quinze années suivantes, jusqu'à sa mort, il écrivit nombre de commentaires sur l'Écriture, souvent pour expliquer ses choix de traduction. Sa connaissance de l'hébreu donne également à ses traités exégétiques (en particulier ceux écrits après 386) une valeur supérieure à celle de la plupart des commentaires patristiques, même si Jérôme a un penchant marqué pour les subtilités allégoriques et mystiques à la manière de Philon et de l'École d'Alexandrie. Ses commentaires peuvent se ranger en trois catégories:

Des traductions ou adaptations de ses prédécesseurs grecs, comprenant quatorze homélies d'Origène sur Jérémie et le même nombre sur Ézéchiel (traduites vers 380 à Constantinople), deux homélies d'Origène sur le Songe de Salomon (Rome, vers 383), trente-neuf sur Luc (Bethléem, 389). La traduction des neuf homélies d'Origène sur Ésaïe que l'on comprend dans les œuvres de Jérôme ne sont pas de lui. On peut faire mention ici de son importante contribution à la connaissance de la topographie de la Palestine, par le biais de son De situ et nominibus locorum Hebraeorum, qui est une traduction comprenant des additions - et de regrettables omissions - de l'Onomasticon d'Eusèbe. De la même période (390), on peut mentionner le Liber interpretationis nominum Hebraicorum, qui se fonde sur un livre qui prend sans doute sa source chez Philon, pour être ensuite amplifié par Origène.

Des commentaires originaux sur l'Ancien Testament. De son installation à Bethléem et des cinq années suivantes date une série de brèves études de l'Ancien Testament : De seraphim, De voce Osanna, De tribus quaestionibus veteris legis (que l'on classe généralement dans la Correspondance aux chiffres 18, 20 et 36), Quaestiones hebraicae in Genesin, Commentarius in Ecclesiasten, Tractatus septem in Psalmos 10 - 16 (perdu), Explanationes in Michaeam, Sophoniam, Nahum, Habacuc, Aggaeum. Vers 395, il composa une série de commentaires plus longs, portant d'abord sur les sept petits prophètes restant, puis sur Isaïe (395-400), Daniel (407), Ezéchiel (410-415) et Jérémie (415, inachevé).

Des commentaires sur le Nouveau Testament. Ces derniers comprennent seulement les épîtres à Philémon, aux Galates, aux Ephésiens et à Tite (composé à la hâte vers 387-388), les Évangiles de Matthieu (écrit en deux semaines, 398), Marc, quelques passages de Luc, le prologue de Jean et l'Apocalypse. Ayant écrit ce dernier avec la hâte qui lui était coutumière, il se servit d'un extrait du commentaire de Tichonius, un Africain, qui nous est préservé sous la forme d'une sorte de préface au début d'un ouvrage plus long du prêtre espagnol Beatus de Libana. Auparavant, il avait réservé un autre traitement au livre de l'Apocalypse : il avait retravaillé un commentaire de Victorinus (saint) (303); en désaccord avec les vues millénaristes de ce dernier, il avait substitué à la conclusion millénariste de celui-ci un exposé spiritualisant personnel, ajouté une introduction et introduit quelques changements dans le texte.

Écrits historiques

Une des premières tentatives de Jérôme dans le domaine de l'histoire fut son Temporum liber, composé aux environs de 380 à Constantinople. Il s'agit d'une transposition en latin des tables chronologiques mises en place dans la seconde partie de la Chronique d'Eusèbe, avec un supplément pour la période 325-379. En dépit de nombreuses erreurs venant d'Eusèbe et d'autres dues à Jérôme, son travail est de valeur, ne serait-ce que pour l'impulsion qu'il donna à des chroniqueurs plus tardifs comme Prosper, Cassiodore et Victor de Tannuna. Nous lui devons également trois hagiographies (les trois premières en langue latine, qui influenceront Sulpice-Sévère dans l'écriture de sa Vie de saint Martin): la Vie du moine Paul, écrite pendant son premier séjour à Antioche (376), la Vie de Malch (391) qui se fonde probablement sur un travail antérieur, même s'il prétend avoir pour source des discussions avec l'ascète Malch lui-même dans le désert de Calchis, et la Vie d'Hilarion (même date), dont la matière historique est plus fiable que les deux précédentes, et repose en partie sur une biographie d'Epiphanius, et en partie sur la tradition orale. Ce que l'on nomme le Martyrologium sancti Hieronymi est apocryphe : c'est manifestement l'œuvre d'un moine occidental à la fin du VIe siècle ou au début du VIIe, qui se réfère ouvertement au chapitre d'ouverture de la Vie de Malch, où Jérôme fait part de son intention d'écrire une histoire des saints et des martyrs à partir de l'époque apostolique. Le plus important des travaux historiques de Jérôme est le livre De viris illustribus, écrit à Bethléem en 392, dont le titre et la structure sont empruntés à Suétone. Il contient de brèves notices biographiques et littéraires sur 135 auteurs chrétiens, de Pierre à Jérôme lui-même. Pour les 78 premiers, sa source principale est Eusèbe de Césarée (Historia ecclesiastica); la seconde partie, qui commence avec Arnobe et Lactance, comprend une bonne dose d'informations indépendantes, particulièrement en ce qui concerne les auteurs occidentaux.

Correspondance

La Correspondance de Jérôme constitue la partie la plus intéressante de son œuvre conservée par la variété de la matière et la qualité du style. Qu'il discute de points d'érudition, évoque des cas de conscience, réconforte les affligés, tienne des propos plaisants avec ses amis, vitupère contre les vices de son époque, exhorte à la vie ascétique et à la renonciation au monde, ou joute contre ses adversaires théologiques, il offre une peinture vivante non seulement de son esprit, mais également de son époque et de ses caractéristiques particulières. Les lettres les plus reproduites ou les plus citées sont des lettres d'exhortation : ep. 14 Ad Heliodorum de laude vitae solitariae, ep. 22 Ad Eustochium de custodia virginitatis, ep. 52 Ad Nepotianum de vita clericorum et monachorum, une sorte de résumé de la théologie pastorale vue sous l'angle ascétique, ep. 53 Ad Paulinum de studio scripturarum, ep. 57 au même : De institutione monachi, ep. 70 Ad Magnum de scriptoribus ecclesiasticis, et ep. 107, Ad Laetam de institutione filiae.

Œuvre théologique

La quasi-totalité de la production de Jérôme dans le domaine doctrinal a un caractère polémique plus ou moins affirmé. Elle est dirigée contre des adversaires de la doctrine orthodoxe. Même sa traduction du traité de Didyme sur l'Esprit Saint en latin (commencé à Rome en 384 et continué à Bethléem) fait preuve d'une tendance à l'apologétique contre les Ariens et les tenants de la doctrine pneumatiste. Il en est de même de sa version du De principiis d'Origène (vers 399), dont la vocation est de suppléer à la traduction inappropriée de Rufin. Les écrits polémiques au sens strict couvrent la totalité de la carrière littéraire de Jérôme. Pendant ses séjours à Antioche et Constantinople, il dut s'occuper de la controverse arienne, et particulièrement des schismes provoqués par Mélitios et Lucifer de Cagliari. Dans deux lettres au pape Damase (ep. 15 et 16), il se plaint de la conduite des deux partis à Antioche, les Mélétiens et les Pauliniens, qui ont tenté de le faire participer à leur controverse sur l'application des termes « ousia » et « hypostasis » à la Trinité. À la même époque, ou un peu plus tard (379), il rédige son Liber contra Luciferianos, où il fait un usage adroit du dialogue pour combattre les meneurs de cette faction. À Rome, vers 383, il écrivit une vibrante tirade contre l'enseignement d'Helvidius, pour défendre la doctrine de la virginité perpétuelle de Marie et la supériorité du célibat sur l'état conjugal. Il trouva un opposant similaire en la personne de Jovinianus, avec qui il entra en conflit en 392 (Adversus Jovinianum, et l'apologie de ce texte, que l'on trouve dans une lettre à son frère Pammachius, ep. 48). Une fois de plus, il prit la défense les pratiques catholiques traditionnelles de la piété et sa propre éthique ascétique en 406, contre le prêtre espagnol Vigilantius, qui s'opposait au culte des martyrs et des reliques, au vœu de pauvreté, et au célibat du clergé. C'est à cette époque que débuta la controverse avec Jean de Jérusalem et Rufin sur l'orthodoxie d'Origène. C'est à cette époque qu'appartiennent ses polémiques les plus passionnées et les plus globales: le Contra Joannem Hierosolymitanum (398 ou 399), les deux Apologiae contra Rufinum qui y sont intimement liées (402), et le « dernier mot » écrit quelques mois plus tard, Liber tertius seu ultima responsio adversus scripta Rufini. Le dernier de ses écrits polémiques est le dialogue Contra Pelagianos (415).

Position théologique

Jérôme fait sans conteste partie des plus érudits des Pères occidentaux. Dans l'Église catholique romaine, il est reconnu comme le saint patron des bibliothécaires et des traducteurs. Sa supériorité vient notamment de sa connaissance de l'hébreu. Il est vrai qu'il était tout à fait conscient de ses qualités, et qu'il ne se libéra jamais de la tentation de mépriser ses rivaux, particulièrement Ambroise. Son érudition n'est cependant pas dépourvue de faiblesses. Il connaissait bien la littérature grecque et latine, païenne aussi bien que chrétienne, mais on peut parfois constater des manques ou des traces de superficialité. En outre, sa connaissance de l'hébreu prête le flanc à de nombreuses attaques de la part de la critique moderne.

D'une façon générale, ce n'est pas son savoir absolu qui en fait un auteur exceptionnel, mais une élégance proche de la poésie, un esprit incisif, une capacité reconnue à adapter des sentences ou des proverbes connus à ses visées, et une tendance lourde à rechercher les effets rhétoriques. Ses faiblesses sont plus notables sur les points de dogme. Il n'a contribué qu'indirectement au développement de la doctrine. On peut en dire de même de sa contribution à la théologie morale, où il faisait preuve moins d'un intérêt pour la spéculation abstraite portant sur la morale que d'un zèle ascétique obsessionnel et d'un enthousiasme passionné pour l'idéal monastique. C'est pour cette attitude que Martin Luther le jugea d'une façon si sévère. Il fait preuve d'un réel défaut d'indépendance et d'une soumission à la tradition orthodoxe. C'est dans cet esprit qu'il vivait avec le pape Damase, ne faisant jamais preuve du moindre esprit de décision. Quand l'Église dut décider s'il fallait reconnaître avec les Mélétiens l'existence de trois hypostases de l'ousia divine ou, avec les Pauliniens, une hypostase avec trois personnes (prosopa), Jérôme écrit: « Décide, je t'en prie, et je n'aurai pas peur de parler de trois hypostases ». On peut en faire le précurseur de l'ultramontanisme. Sa tendance à reconnaître la supériorité d'autrui ne se manifeste pas moins dans sa correspondance avec Augustin d'Hippone (ep. 56, 67, 102-105, 110-112, 115-116 pour Jérôme, et 28, 39, 40, 67-68, 71-75, 81-82 pour Augustin).

Cependant, en dépit des défauts et des faiblesses évoquées, Jérôme a sa place parmi les Pères d'Occident, ne serait-ce que par l'influence immense de sa version de la Bible sur le développement ultérieur de l'Église et de la théologie. Son accession au rang de saint et de docteur de l'Église catholique ne fut possible que parce qu'il rompit toute relation avec l'école théologique qui avait assuré sa formation, celle des Origénistes.

Iconographie

Prêtre romain, Jérôme de Stridon est traditionnellement représenté en cardinal. Même lorsqu'il est représenté comme un anachorète avec une croix, un crâne et une Bible pour toute ornementation de sa cellule, on utilise généralement le chapeau rouge ou un autre signe pour indiquer son rang. L'iconographie de Jérôme de Stridon a fait souvent appel à sa légende: par exemple, sa pénitence au désert (Léonard de Vinci - 1480 - pinacothèque vaticane - Rome) ou encore retirant l'épine de la patte d'un lion (Vittore Carpaccio - Venise) Il est l'un des quatre principaux Pères de l'Église latins, et il est à ce titre souvent représenté aux côtés de l'évêque Augustin d'Hippone, de l'archevêque Ambroise de Milan et du pape Grégoire Ier. Les chrétiens d'Occident le vénèrent comme saint et le fêtent le 30 septembre. Il est fêté le 15 juin julien ou le 15 juin grégorien par l'Église orthodoxe. Il est le patron des traducteurs.