Lessico

Kiwi - Apteryx

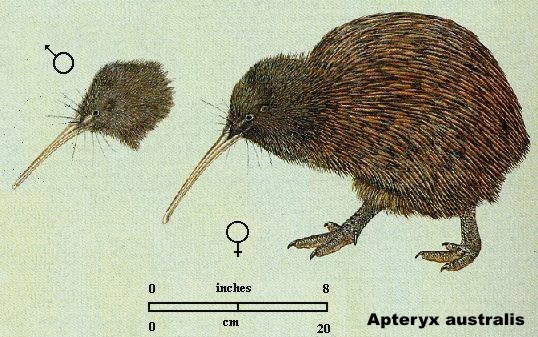

Il Kiwi - il cui nome deriva dai sottili e trillanti ki-wi lanciati dai maschi - appartiene alla famiglia degli Apterigidi, cioè soggetti senza ali, gli struzioniformi più primitivi, anche se accomunati da ben pochi caratteri con gli altri struzioniformi, se si eccettua la mancanza di carena sternale e la disposizione delle ossa del palato. A un’osservazione superficiale sembra addirittura che il Kiwi non sia legato a nessun gruppo di uccelli. Le femmine sono più grandi dei maschi e il loro peso è rispettivamente di 3 e di 2 Kg.

Ambedue le

ovaie - ovviamente della femmina - sono funzionanti, ma viene utilizzato un

solo ovidutto, il sinistro, essendo quello destro per lo più inutilizzato, e

raramente vestigiale. Si veda per completezza la ricerca di Kinsky (1971) The

consistent presence of paired ovaries in the Kiwi (Apteryx) with

some discussion of this condition in other birds![]() .

.

Si distinguono 2 specie:

Apteryx

australis -

Apterice australe - Kiwi striato - con 3 sottospecie:

Apteryx australis australis - Kiwi striato del sud

Apteryx australis mantelli - Apterice di Mantell - Kiwi striato del

nord

Apteryx australis lawryi - Kiwi di Stewart

Apteryx

owenii -

Apterice di Owen - Kiwi maculato - con 2 sottospecie:

Apteryx owenii owenii - Kiwi pigmeo - Kiwi maculato minore

Apteryx owenii haastii - Kiwi di Haast - Kiwi maculato maggiore ![]()

Sono uccelli prettamente notturni che durante il giorno rimangono nascosti in cavità, abitualmente protette da una fitta vegetazione. La ricerca di cibo viene effettuata quasi sempre durante la notte, e sempre in zone con folta vegetazione, ove l’unico indizio della loro presenza sono i sottili e trillanti ki-wi lanciati dai maschi o il leggero kör-kör delle femmine. Si nutrono di insetti, di lombrichi stanati col lungo becco, di bacche cadute al suolo. Il Kiwi non vola, è rivestito di penne molli e cascanti che danno più l’idea di peli che di piume, ha le narici alla punta del becco con olfatto eccellente.

Il Kiwi striato del nord depone abitualmente 2 uova, lasciando intercorrere spesso più di una settimana tra una deposizione e l’altra. I Kiwi striati del sud covano un solo uovo alla volta. L’uovo, dalla forma allungata di circa 12 cm, pesa 450 gr, cioè ben il 14% del peso della femmina. Lo struzzo, che può pesare oltre 150 kg, depone uova di circa 15 cm e di 1,5 kg che rappresentano l’1% del peso materno.

Una gallinella Nagasaki con doppio fattore dell’arricciato, quindi praticamente implume, salvo le ali munite di penne a fil di ferro, che tengo in osservazione da qualche mese, pesa 500 gr e depone uova di 25 gr in media, pari al 5% del suo peso corporeo. Un’ovaiola può deporre uova di 60 gr, ma corrisponderanno pur sempre solo al 2,5% del suo peso, che in media è di 2,5 kg.

Per cui si può affermare che l’uovo del Kiwi è il più grosso del regno ornitologico, almeno in senso relativo, rapportato cioè alla mole della genitrice. Ma quello che è ancor più strano, rapportato alla gallina, è il fatto che, per fabbricare tale uovo, la femmina di Kiwi impiega ben 34 giorni. Un record assoluto. Inoltre il 60% del contenuto è costituito da tuorlo, mentre nella gallina l’albume pesa circa il 66% dell’intero uovo.

Il maschio

di Kiwi si occupa della cova (fa eccezione l'Apteryx owenii haastii in

quanto covano sia il maschio che la femmina, la quale depone solo un uovo) che dura 83-93 giorni, in capo ai

quali il poveretto, già più mingherlino della compagna, ha perso il 20% del

suo peso. Nel frattempo la femmina rimane fedele al marito, non si comporta

cioè come le femmine dei Falaropi![]() e delle

Jacane

e delle

Jacane![]() che

praticano la poliandria. Da notare tuttavia che la poliandria è in grado di

assicurare un maggior numero di discendenti. Forse anche per questo il Kiwi è

diventato sempre più raro.

che

praticano la poliandria. Da notare tuttavia che la poliandria è in grado di

assicurare un maggior numero di discendenti. Forse anche per questo il Kiwi è

diventato sempre più raro.

Bernhard

Grzimek

Vita degli animali - 1974

Kiwi - Apteryx

I kiwi (Apteryx, Shaw 1813) sono un genere di uccelli che vivono in Nuova Zelanda appartenenti all'ordine degli Struthioniformes. I kiwi sono rappresentati da cinque specie con 6-8/9 sottospecie, 2/3 delle quali ancora da definire, e una specie estinta:

Apteryx

australis

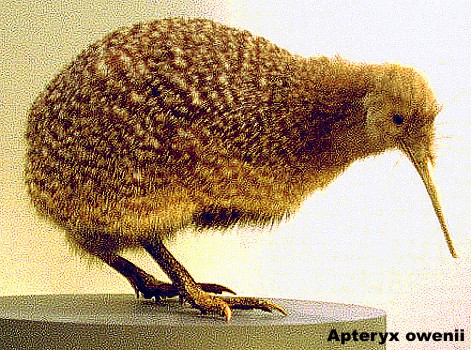

Apteryx owenii

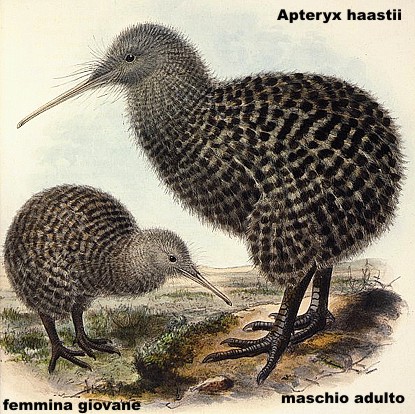

Apteryx haastii![]()

Apteryx rowi

Apteryx mantelli

I kiwi, endemici della Nuova Zelanda, sono una famiglia molto antica, la più antica tra quelle di uccelli viventi in Nuova Zelanda. I progenitori di questa famiglia vivevano in Gondwana e raggiunsero le terre che formano l'attuale Nuova Zelanda passando dalla parte occidentale dell'Antartide prima della separazione avvenuta intorno a 70 milioni di anni fa. Le prime tracce fossili risalgono al Quaternario. La linea evolutiva dei kiwi si separò da quella degli Struzioniformi in tempi molto remoti, ancora prima di perdere l'attitudine al volo. La differenziazione fra le varie specie è piccola.

I kiwi sono morfologicamente differenti dagli altri rappresentanti dell'ordine, sono i rappresentanti più piccoli con un peso che va dal 1 kg del kiwi maculato minore ai 3-5 kg del kiwi australe per una lunghezza compresa fra i 35 e i 65 cm. Gli esemplari di sesso femminile sono più grandi dei maschi della stessa specie, soprattutto poco prima di deporre le uova. La testa è relativamente piccola con un collo lungo e piuttosto robusto. I muscoli toracici sono poco sviluppati mentre tutta la parte inferiore del corpo (bacino, zampe e piedi) è molto robusta, l'insieme ricorda la forma di una pera.

Le ali sono lunghe solamente 4-5 centimetri e nascoste sotto le piume con un uncino all'estremità, la coda è assente. Le zampe sono particolarmente robuste, dotate di potenti muscoli terminanti con piedi aventi quattro dita con robusti artigli, tre in avanti e uno più piccolo indietro, mentre gli altri struzioniformi ne hanno solo due o tre. Sono anche buoni nuotatori.

I sensi sono adatti al tipo di vita che conducono, si muovono normalmente di notte nel sottobosco, quindi sono dotati di buon olfatto e udito, con grandi cavità auricolari esterne per cui localizzano la provenienza dei suoni girando la testa nella direzione giusta. La vista è invece ridotta con occhi piccoli e frontali funzionanti solo a breve distanza.

Il becco dei kiwi è lungo e flessibile, leggermente incurvato verso il basso, il colore varia dal bianco avorio al rosa fino al brunastro con la mandibola inferiore più spessa di quella superiore. Il becco del kiwi australe misura circa 20 cm nel maschio e 25 nella femmina. Il kiwi spesso usa appoggiarsi con la punta del becco, quasi come una terza zampa. Caratteristica particolare del becco sono le narici poste sulla sua cima che lo aiutano nella localizzazione di invertebrati che vivono in prossimità della superficie del terreno. Sulla base del becco si aprono delle valvole per espellere acqua e impurità dalle narici rendendo agevole alimentarsi in luoghi paludosi. La lingua dei kiwi è appuntita e callosa. Alcune penne intorno alla base del becco si sono trasformate in setole tattili.

Le piume degli Apteryx, dall'aspetto ispido, somigliano più a peli che a penne e mancano degli uncini sulle barbule come negli altri ratiti. Non ci sono particolari differenze nel piumaggio fra i sessi o per l'età, soltanto nei più giovani appare più morbido. Pare non ci sia una vera e propria muta del piumaggio, piuttosto un continuo rinnovamento.

L'ambiente ideale per il kiwi è la foresta pluviale ma è riuscito ad adattarsi anche ad altri ecotipi costretto dalla riduzione della superficie coperta da questo tipo di foreste. Lo si può trovare anche nelle foreste subtropicali o temperate ma anche nelle praterie e nelle macchie fra gli arbusti. Il kiwi australe si è adattato anche alle foreste monospecie di pino. Necessita di un terreno relativamente morbido dove poter scavare la tana, e ricco di humus dove trova le sue prede. Le tane si trovano di solito ai margini delle foreste nelle scarpate umide più facili da scavare. È essenziale che il clima sia caldo e umido ma si adatta a vivere dal livello del mare fino a 1.200 m d'altezza. Le varie specie non presentano differenze per quanto riguarda l'habitat.

Il kiwi si muove soprattutto di notte, durante le ore di luce rimane nascosto nella tana o in altri anfratti e queste abitudini ne hanno reso difficile lo studio. Negli ultimi anni tecnologie come i visori notturni o la radiolocalizzazione hanno contribuito a svelare qualche particolare in più della vita di questi animali. I kiwi sono animali territoriali, vivono in coppie a meno che non siano giovani individui o alla ricerca di un compagno. La dimensione del territorio varia con l'abbondanza del cibo e la densità degli individui. Una coppia di kiwi australi occupa un'area fra i 5 e i 50 ettari, il kiwi maculato maggiore spazia fra gli 8 e i 25 ettari mentre il kiwi maculato minore si accontenta di 2 o 3 ettari. Entrambi gli individui della coppia scacciano qualunque individuo entri nel territorio, soprattutto nella stagione riproduttiva. I kiwi australi si dimostrano più tolleranti, ammettendo una parziale sovrapposizione dei territori.

I kiwi scavano tane, dove costruiscono anche il nido, lunghe diversi metri con un imbocco di 10-15 cm nascosto fra le piante e terminanti con una camera abbastanza ampia da contenere due adulti. A seconda dei casi sono utilizzate per anni oppure cambiate più frequentemente. L'uovo di kiwi può raggiungere fino al 15% del peso della madre. Sono animali simpatici, molto socievoli. I kiwi sono animali amati in Nuova Zelanda, al contrario dei nemici Opossum.

Kiwi è anche il nome del frutto dell'Actinidia chinensis. Questa pianta, originaria della Cina, fu introdotta agli inizi del XX secolo in Nuova Zelanda dove, per la somiglianza, venne spontaneo soprannominare la bacca, munita di buccia marroncina e pelosa, col nome di questi piccoli uccelli caratteristici della regione. Dalla Nuova Zelanda, principale produttrice di kiwi, la coltivazione dell'Actinidia chinensis si è poi diffusa in tutto il mondo, trascinando con sé il nomignolo neozelandese.

Un piccolo kiwi giallo, munito di scarpe da ginnastica, è il protagonista di The New Zealand Story, videogioco arcade sviluppato nel 1988 dalla Taito, dove, ad ogni livello, il simpatico animaletto di nome Tiki dovrà riuscire a liberare i suoi amici, catturati ed ingabbiati da un tricheco. Un kiwi (Scritto da Andrea Zingoni) è protagonista di un cartone animato in onda su Rai 3 dal titolo: Le ricette di Arturo e Kiwi. I kiwi sono presenti anche nel mondo dei fumetti: uno è Angus Fangus, giornalista neozelandese di 00 Channel, presente nella serie PKNA della Disney, l'altro appare col nome di Apteryx nelle strisce di B.C. di Johnny Hart. Kiwi è il nomignolo con cui, nei paesi di lingua anglosassone, sono spesso chiamati i neozelandesi in generale. Il kiwi ha stuzzicato anche la fantasia di un giovane animatore, Dony Permedi: il suo video ha superato i 20 milioni di visualizzazioni in poco più di due anni. Il kiwi è stato il primo simbolo della scuderia di Formula 1 McLaren, fondata dall'omonimo Bruce McLaren originario della Nuova Zelanda.

The widely recognised origin for the name Kiwi is from the Maori language (1825–1835) and as "of imitative origin" from the call. However, there is another theory that the name stems from the fact that, with its long decurved bill and hairy brown body, it is similar to the Polynesian word kivi, used for the bristle-thighed curlew. So when the first settlers arrived, they simply reused this word for the new found bird The genus name Apteryx is Greek, meaning without wing: a-, without or not; pteryx, wing.

Kiwi are flightless birds endemic to New Zealand, in the genus Apteryx and family Apterygidae. The kiwi is a national symbol of New Zealand. At around the size of a domestic chicken, kiwi are by far the smallest living ratites and lay the largest egg in relation to their body size. There are five recognised species - all of which are endangered. There are five accepted species of kiwi (one of which has four sub-species), plus one to be formally described.

Apteryx

haastii - Great spotted kiwi![]()

Apteryx owenii - Little spotted kiwi

Apteryx rowi - Okarito brown kiwi

Apteryx australis - Brown kiwi

Apteryx mantelli - North island brown kiwi

The largest species is the Great Spotted Kiwi or Roroa, Apteryx haastii, which stands about 45 cm (18 in) high and weighs about 3.3 kg (7.3 lb). (Males about 2.4 kg (5.3 lb)) It has grey-brown plumage with lighter bands. The female lays just one egg, with both sexes incubating. Population is estimated to be over 20,000, distributed through the more mountainous parts of northwest Nelson, the northern West Coast, and the Southern Alps. The Maori name for the Great Spotted Kiwi is roroa, or roa.

The very small Little Spotted Kiwi, Apteryx owenii is unable to withstand predation by introduced pigs, stoats and cats and is extinct on the mainland because of these reasons. About 1350 remain on Kapiti Island and it has been introduced to other predator-free islands and appears to be becoming established with about 50 'Little Spots' on each island. A docile bird the size of a bantam, it stands 25 cm (9.8 in) high and the female weighs 1.3 kg (2.9 lb). She lays one egg which is incubated by the male. The Maori name for the Little Spotted Kiwi is kiwi pukupuku.

The Rowi, also known as the Okarito Brown Kiwi or Apteryx rowi, is a recently identified species, slightly smaller, with a greyish tinge to the plumage and sometimes white facial feathers. Females lay as many as three eggs in a season, each one in a different nest. Male and female both incubate. Distribution of these kiwi are limited to a small area on the west coast of the South Island of New Zealand, however studies of ancient DNA have revealed that in prehuman times it was far more widespread up the west coast of the South Island and was present in the lower half of the North Island where it was the only kiwi species detected.

The Tokoeka, Apteryx australis, relatively common species of kiwi known from south and west parts of South Island that occurs at most elevations. It is approximately the size of the Great Spotted Kiwi and is similar in appearance to the Brown Kiwi but its plumage is lighter in colour. Ancient DNA studies have shown that in prehuman times the distribution of this species included the east coast of the South Island. There are several subspecies of the Tokoeka recognised.

The North Island Brown Kiwi, Apteryx mantelli or Apteryx australis before 2000 (and still in some sources), is widespread in the northern two-thirds of the North Island and, with about 35,000 remaining, is the most common kiwi. Females stand about 40 cm (16 in) high and weigh about 2.8 kg (6.2 lb), the males about 2.2 kg (4.9 lb). The North Island Brown has demonstrated a remarkable resilience: it adapts to a wide range of habitats, even non-native forests and some farmland. The plumage is streaky red-brown and spiky. The female usually lays two eggs, which are incubated by the male.

Analysis of mitochondrial DNA, ecology, behaviour, morphology, geographic distribution and parasites of the North Island Brown Kiwi has led scientists to propose that the Brown Kiwi is three distinct species. The North Island Brown Kiwi; the Okarito Brown Kiwi (Rowi), whose distribution is restricted to a single site on the West Coast of the South Island of New Zealand; and a third distinct population of the North Island Brown Kiwi, the Southern Tokoeka, distributed in the in lowland forest to the north of Franz Josef glacier in the South Island and on Stewart Island/Rakiura, with a small population near Haast being another possibly distinct species, the Haast Tokoeka.

It was long presumed that the kiwi's closest relatives were the other New Zealand ratites, the moa. However, recent DNA studies indicate that the Ostrich is more closely related to the moa and the kiwi's closest relatives are the Emu and the cassowaries. This theory suggests that the kiwi's ancestors arrived in New Zealand from elsewhere in Australasia well after the moa. According to British scientists, the kiwi may be an ancient import from Australia. Researchers at Oxford University have found DNA evidence connected to Australia's Emu and the Ostrich of Africa. Upon examining DNA from New Zealand's native moa, they believe that the kiwi is more closely related to its Australian cousins.

Prior to the arrival of humans in the 13th century or earlier, New Zealand's only endemic mammals were three species of bat, and the ecological niches that in other parts of the world were filled by creatures as diverse as horses, wolves and mice were taken up by birds (and, to a lesser extent, reptiles).

Kiwi are shy and usually nocturnal. Their mostly nocturnal habits may be a result of habitat intrusion by predators, including humans. In areas of New Zealand where introduced predators have been removed, such as sanctuaries, kiwi are often seen in daylight. They prefer subtropical and temperate podocarp and beech forests, but they are being forced to adapt to different habitat, such as sub-alpine scrub, tussock grassland, and the mountains. Kiwi have a highly developed sense of smell, unusual in a bird, and are the only birds with nostrils at the end of their long beak. Kiwi eat small invertebrates, seeds, grubs, and many varieties of worms. They also may eat fruit, small crayfish, eels and amphibians. Because their nostrils are located at the end of their long beaks, Kiwi can locate insects and worms underground without actually seeing or feeling them, due to their keen sense of smell.

Once bonded, a male and female kiwi tend to live their entire lives as a monogamous couple. During the mating season, June to March, the pair call to each other at night, and meet in the nesting burrow every three days. These relationships may last for up to 20 years.

As some

other birds they have a functioning pair of ovaries, but only an oviduct is

used, the left, being the right unused, and rarely vestigial. See the research of Kinsky (1971) The

consistent presence of paired ovaries in the Kiwi (Apteryx) with

some discussion of this condition in other birds![]() .

.

Kiwi eggs can weigh up to one quarter the weight of the female. Usually only one egg is laid per season. The kiwi lays the biggest egg in proportion to its size of any bird in the world, so even though the kiwi is about the size of a domestic chicken, it is able to lay eggs that are about six times the size of a chicken's egg. Eggs are smooth in texture, and are ivory or greenish white. The male incubates the egg, except for the Great spotted kiwi, Apteryx haastii, where both parents are involved. The incubation period is 63-92 days. Producing the huge egg places a lot of demands on the female. For the thirty days it takes to grow the fully developed egg the female must eat three times her normal amount of food. Two to three days before the egg is laid there is little space left inside the female for her stomach and she is forced to fast.

Their adaptation to a terrestrial life is extensive: like all ratites they have no keel on the breastbone to anchor wing muscles, and barely any wings. The vestiges are so small that they are invisible under the kiwi's bristly, hair-like, two-branched feathers. While birds generally have hollow bones to minimise weight and make flight practicable, kiwi have marrow, in the style of mammals. With no constraints on weight from flight requirements, some Brown Kiwi females carry and lay a single 450 g (16 oz) egg. Like most other ratites, they have no preen gland. Their bill is long, pliable, and sensitive to the touch, and their eyes have a reduced pecten. Their feathers lack barbules, and aftershafts, and they have large vibrissae around the gape. They have 13 flight feathers, no tail, just a small pygostyle. Finally, their gizzard is weak and their caeca is long and narrow.

Maori traditionally believe that kiwi are under the protection of Tane Mahuta, god of the forest. Kiwi feathers are particularly important to Maori, as they are used for kahu-kiwi – ceremonial cloaks. Today, while kiwi feathers are still used, they are gathered from kiwi that die naturally or through road accidents or predation, and Maori no longer hunt kiwi, but consider themselves their guardians.

The first kiwi specimen to be studied by Europeans was a kiwi skin brought to George Shaw by Captain Andrew Barclay aboard the ship Providence, who was reported to have been given it by a sealer in Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) around 1811. George Shaw gave the kiwi its scientific name and drew sketches of the way he imagined a live bird to look which appeared as plates 1057 and 1058 in volume 24 of The Naturalist's Miscellany in 1813.

The kiwi as a symbol first appeared in the late 19th century in New Zealand regimental badges. It was later featured in the badges of the South Canterbury Battalion in 1886 and the Hastings Rifle Volunteers in 1887. Soon after, kiwis appeared in many military badges, and in 1906 when Kiwi Shoe Polish was widely sold in the UK and the USA the symbol became more widely known. During the First World War, the name "kiwi" for New Zealand soldiers came into general use, and a giant kiwi, (now known as the Bulford Kiwi), was carved on the chalk hill above Sling Camp in England. Use has now spread so that now all New Zealanders overseas and at home are commonly referred to as "kiwis". The kiwi has since become the most well-known national symbol for New Zealand, and kiwis are prominent in the coat of arms, crests and badges of many New Zealand cities, clubs and organisations. The New Zealand dollar is often referred to as "the kiwi".

Kiwi

maculato maggiore

Apteryx haastii

Il kiwi maculato maggiore (Apteryx haastii, Potts 1872) è un uccello del genere Apteryx diffuso nell'Isola del Sud (Nuova Zelanda): a occidente tra Nelson e Westland, probabilmente anche nel Fiordland. È stato inoltre introdotto nell'isola Little Barrier. È relativamente comune nel suo areale poiché, a differenza del suo parente di minori dimensioni Apteryx owenii, è molto diffidente ed elusivo. Il maschio è alto tra 50 e 60 cm, con un peso che varia dai 1215 ai 2610 g, e ha il becco lungo tra i 90 e i 100 mm. La femmina presenta le stesse dimensioni ma pesa di più (1530-3270 g) e ha il becco più lungo, tra i 125 e i 135 mm. Essa possiede ambedue le ovaie funzionanti - come tutte le altre specie di Apteryx - e collabora col maschio nella cova dell'unico uovo annuale che depone.

Great Spotted Kiwi

Apteryx haastii

The Great Spotted Kiwi, Great gray kiwi, or Roroa, Apteryx haastii, is a species of kiwi endemic to the South Island of New Zealand. The Great Spotted Kiwi, as a member of the Ratites, is flightless. It is the largest of the kiwi. The rugged topography and harsh climate of the high altitude, alpine, part of its habitat render it inhospitable to a number of introduced mammalian predators , which include dogs, ferrets, pigs and stoats. Because of this, populations of this species have been less seriously affected by the predations of these mammals compared to other species of Kiwi. Nonetheless, there has been a 43% decline in population in the past 45 years, due to the predations of these invasive species and habitat destruction. This has led it to be classified as vulnerable. There are about 22,000 Great Spotted Kiwis in total, almost all in the more mountainous parts of northwest Nelson, the northwest coast, and the Southern Alps. A minority live on islands.

This kiwi is highly aggressive, and pairs will defend their large territories (49 acres) against other kiwi. Great Spotted Kiwi are nocturnal, and will sleep during the day in burrows. At night, they feed on invertebrates and will also eat plants. Great Spotted Kiwi breed between June and March. The egg is the largest of all birds in proportion to the size of the bird. Chicks take 75 to 85 days to hatch, and after hatching, they are abandoned by their parents.

This large kiwi is one of five species of kiwis residing in New Zealand. The other four are the Tokoeka (Apteryx australis), Okarito Brown Kiwi (Apteryx rowi), Little Spotted Kiwi (Apteryx owenii), and North Island Brown Kiwi (Apteryx mantelli). Great Spotted Kiwis are related closest to the Little Spotted Kiwi. The Kiwi genus, Apteryx, is endemic to only New Zealand. 44% of the bird species native to New Zealand are endemic. Kiwis are placed in the Ratite family, which also includes the Emu, Ostrich, Rhea, and Cassowary. All Ratites are flightless. Kiwi are closely related to the extinct Moa bird that once inhabited New Zealand.

Before the Great Spotted Kiwi was discovered, several stories circulated about the existence of a large kiwi called the Maori Roaroa. In 1871, two specimens were brought to the Canterbury Museum, where they were identified as a new species and were named after the museum's curator, Dr. Haast. The genus name, Apteryx, comes from the Ancient Greek words a "without" or "no", and pteryx, "wing" and haastii is the Latin form of the last name of Sir Julius von Haast.

Great Spotted Kiwis are the largest of the kiwis; the male is 45 cm (18 in) tall, while the female is 50 cm (20 in) tall. Bill length ranges from 9–12 cm (3.5–4.7 in), while weight ranges between 1.2 and 2.6 kg (2.6 and 5.7 lb) for males and 1.5 and 3.3 kg (3.3 and 7.3 lb) for females. The body is pear-shaped, while the head and neck is small with a long slender ivory bill. The Great Spotted Kiwi, along with the other Kiwi species, is the only bird with nostrils at the end of its bill. The eyes are small and do not see well, as it relies mostly on its sense of smell. The legs are short, with four toes per foot. It has a plumage composed of soft, hair-like feathers, which have no aftershafts. The plumage can range from charcoal gray to light brown. They have large vibrissae around the gape, and they have no tail, only a small pygostyle. The common name of this bird comes from black spots on its feathers. They use their powerful legs and claws for defense against predators like stoats or ferrets. Kiwis are flightless birds, and this is because Kiwis lack hollow bones, lack a keel to which wing muscles anchor, and have tiny wings. This species also has a low body temperature compared to other birds and are rather fast. They can live for up to fifteen years.

Greater Spotted Kiwis once lived in numerous areas throughout the South Island, but because of predation by invasive species, the remaining kiwi are now restricted to three localities. These kiwi live in higher altitude areas. Populations are present from northwestern Nelson to the Buller River, the northwest coast (Hurunui River to Arthur's Pass), and the Paparoa Range, as well as within the Lake Rotoiti Mainland Island and on Little Barrier Island. The Southern Alps population is particularly isolated. Great Spotted Kiwis reside in complex, maze-like burrows that they construct. Up to fifty burrows can exist in one bird's territory. They will often move around, staying in a different burrow every day. Bird's Nest Fungus sometimes grows in these burrows. Their habitat ranges in elevation from sea level to 1,500 m (4,900 ft), but the majority are concentrated in a range from 700–1,100 m (2,300–3,600 ft) in a subalpine zone. These kiwis will live in tussock grasslands, scrubland, pasture, and forests.

The Great Spotted Kiwi population started declining when European settlers first arrived in New Zealand. Before settlers arrived, about 12 million Great Spotted Kiwis lived in New Zealand. This bird is often preyed upon by invasive pigs, dogs, ferrets and stoats, leading to a 5% chick survival rate. It has more of an advantage than other kiwi species over these predators because it lives in high altitude areas, where the wet upland population thrives. However, there has been a decrease in population of 43% in the past 45 years, and has declined 90% since 1900. Humans have also endangered the species by destroying their habitat by logging forests and building mines. Previously, humans hunted these kiwis for feathers and food. In 1988, the species was listed as Least Concern species. It is currently classified by the IUCN as a vulnerable species. This kiwi has an occurrence range of 8,500 km2 (3,300 sq mi), and in 2000 an estimated 22,000 adult birds remained. They have been trending down about 5.8% a year. The main threat is from predators is mustelids, brush-tailed possum Trichosurus vulpecula, cats, dogs and pigs. The most threatened populations are in the southern areas of the species' range. About 22,000 Great Spotted Kiwis remain. Movements for saving the Kiwi are in place, and sanctuaries for the Great Spotted Kiwi have been made. Thanks to intensive trapping and poisoning efforts the chick survival rate has been raised to about 60% in areas where mammalian pest control is undertaken.

The Great Spotted Kiwi is nocturnal in behavior. If the Kiwis live in an area lacking predators, they will come out in the day. At night, they come out to feed. Like other species of Kiwi, they have a good sense of smell, which is unusual in birds. Males are fiercely territorial. They have bad tempers and will defend their large territories fiercely. At most, four to five Kiwis live in a square kilometer. One pair's territory can be 25 hectares (62 acres) in size. It is not known how they defend such a large territory in proportion to their size. They will call, chase, or fight intruders out. Vocalizations of the Great Spotted Kiwi include growls, hisses, and bill snapping. Great Spotted Kiwi males have a call that resembles a warbling whistle, while the female call is harsh raspy, and also warbling.

In the ground, they dig for earthworms and grubs, and they search for beetles, cicada, crickets, flies, weta, spiders, caterpillars, slugs and snails on the ground. They will also feed on berries and seeds. To find prey, the Great Spotted Kiwi use their scenting skills or feel vibrations caused by the movement of their prey. To do the latter, a kiwi would stick its beak into the ground, then use its beak to dig into the ground. As they are nocturnal, they do not emerge until thirty minutes after sunset to begin the hunt. Kiwis will also swallow small stones, which aid in digestion.

Because adult Great Spotted Kiwis are large and powerful, they are able to fend off most predators that attack them, such as stoats, ferrets, weasels, pigs, brushtails and cats, all of which are invasive species in New Zealand. However, dogs are able to kill even adults. Stoats, ferrets, possums, cats and dogs will feed on the eggs and chicks, meaning most chicks die within their first five months of life. Once the Great Spotted Kiwi was also preyed upon by the Haast's Eagle, which is now extinct.

Great Spotted Kiwis are monogamous, with pairs sometimes lasting twenty years. Nests are made in burrows. The breeding season begins in June and ends in March, as this is when food is plentiful. Males reach sexual maturity at 18 months in captivity, while females are able to lay eggs after three years. In the wild, sexual maturity for both sexes is between ages three and five. Great Spotted Kiwi males chase females around until the females either run off or mate. The pair mates about two to three times during peak activity. The gestation period is about a month. Females do not eat during this period, as the eggs will take up a fourth of a kiwi's body mass. The egg is so large because the yolk takes up 65% of the egg. In most bird eggs, the yolk takes up about 35 to 40% of the egg. This makes the kiwi egg the largest in proportion to the body. Females must rely on fat stored from the previous five months to survive. Because of the large size of the egg, gestation is uncomfortable to the female, and they do not move much. To relieve the pain, females soak themselves in puddles when they come out of the burrows by dipping their abdomens into the puddle. The egg-laying season is between August and January.

After the female lays the egg, the male incubates the egg while the female guards the nest. Males only leave the nest for a few hours to hunt, and during this time, the female takes over. It takes 75 to 85 days for the egg to hatch. The baby kiwi takes 2 to 3 days simply to get out of its egg. Kiwi babies are precocial, and are abandoned by their parents after hatching. After ten days, chicks venture out of the burrow to hunt. Most chicks are killed by predators in the first six months of their life. Great Spotted Kiwis reach full size at year six. Unlike most birds, female Great Spotted Kiwis have two ovaries. Most birds have only one. Great Spotted Kiwis are distinguishable from other kiwi species by the fact that they can only produce one egg a year, as it takes so much energy to produce the massive egg.

The

consistent presence

of

paired ovaries in the Kiwi (Apteryx)

with some discussion of this condition in other birds

by F. C. Kinsky, Wellington, New Zealand – 1971

Excerpt

Introduction

During 1966, while sexing an immature North Island Kiwi (Apteryx australis mantelli Barrier), it was found that the bird was a female and that it had paired ovaries. Both ovaries, showing the same stage of development, were of approximately equal size and well separated from each other. Only one oviduct, the left, was present.

A search through literature revealed only three references to the occurrence of double ovaries within the order Apterygiformes, i.e. Owen (1841:281 and 1849:300), repeated by the same author in 1879, and Fürbringer (1888:1446). These statements seem to have been overlooked by later workers, as no mention can be found of the occurrence of paired ovaries in Apteryx in recent literature.

Following the above chance discovery, every female Apteryx received at the Dominion Museum was carefully examined for paired ovaries and for the possible presence of a right oviduct or its vestigial remnants. In the period from 1967 to 1971, fifty one female Kiwis were received at the Museum and double ovaries were found in all of them. In addition it was found that successful ovulation from either ovary, or from both ovaries alternately within the same laying season, is a normal occurrence. Vestigial remnants of right oviducts were found in 3 instances only.

Previous work on paired ovaries in birds

Normally in birds, as opposed to other vertebrates, only the left ovary and oviduct reach functional development. Textbooks stress this fact, but admit that the order Falconiformes, in various species of which both ovaries may persist, forms an exception to the general rule: van Tyne and Berger (1958 : 38), Marshall (1961 : 193), Welty (1962 : 136), Darling and Darling (1963 : 181), and Thomson (1964 : 691--692). Marshall mentions, in addition (1961 : 193) that "in some nonraptorial species in which asymmetry is usual the primitive bilateral condition not infrequently arises", and also refers to Romanoff and Romanoff (1949 : 176), who state that "the frequency with which the right ovary persists in adult females of certain species is very high". This statement is followed by a small table listing the frequency of paired ovaries found in the following birds:

Hawk 50% (Gunn, 1912); Hawk 47.8% (Picchi, 1911) and Ringdove 23.5%, Common Dove 9.5%, Robin 4.8%, and English Sparrow 4.5% (Riddle, 1925).

Paired ovaries and paired oviducts develop simultaneously during early embryonic development, but both organs on the right side soon regress. Romanoff and Romanoff (1949) point out that the left oviduct in the 4 to 7 day old female chick embryo is already distinctly larger than the right and that in the 9-day old embryo, asymmetry in size, form and structure has become pronounced. At the time of hatching, the right ovary as compared with the left is diminutive and appears to be degenerating. Stanley and Witschi (1940) have found that the regression of the right oviduct in the Red-tailed Hawk begins after the eighteenth day of incubation (i. e. later than in the domestic chick). They also point out that the right oviduct, if persisting at the adult stage, is an inconspicuous vestige, and has never been found in a functional condition in hawks investigated during their studies.

It is difficult to explain the regression and usual disappearance of the right ovary and oviduct during the embryonic stage. Nevertheless, Darling and Darling (1963 : 181) point out that "here is another of the countless weight- saving adaptations found in birds". The authors themselves admit however, that this reasoning is not quite logical, as nearly 50% of all female birds of prey have paired ovaries. Welty (1962) suggests that the reduction in ovaries "from two to one is in part an adaptation to reduce ballast in a flying machine, but also is an arrangement which protects the developing egg. If birds had paired ovaries and oviducts, a sudden jolt of the body, as in alighting, might crack mature eggs located side by side in the parallel oviducts".

Witschi (1935) has found, however, that during the early development of bird embryos primordial germ cells undergo drastic movements and eventually concentrate on the left side. At the beginning of the third day of incubation the primordial germ cells are symmetrically distributed. In the course of the third day the germ cells from the left and right are brought together. This aggregation is immediately followed by a renewed separation of the germ cells into paired strands, of which the left always is the stronger, containing three to ten times as many germ cells as the right strand. The gonads become organized during the fourth day. They consist of a cortex and a medulla. While the gonads are forming, the primordial germ cells invade both cortex and medulla. At the end of the fourth day right and left medullae contain similar numbers of gonia so that the asymmetry arises, mainly if not exclusively, from the small number of germ cells in the right cortex. The author therefore concludes that "the asymmetry in the sex glands of birds is due to a primary, hereditarily fixed deficiency of the right cortical inductor. This deficiency is supposed to express itself in decreased attraction upon the primordial germ cells, especially during the phase of their redistribution in the early part of the third day" of incubation.

The asymmetry of oviducts, according to Witschi (1935) "might have evolved as an adaptation to the aviatic life habits of birds, whereas the more or less complete reduction of the right ovary followed later".

Kumerloeve (1955), mentions that the right side of an embryo contains fewer germ cells than the left side, and that therefore no cortex, or only a reduced cortex, develops. He then expresses the opinion that the regression of the right ovary and consequently of the right oviduct might be owing to lack of space and the increased pressure of other organs situated in the right side of the body cavity, i. e. the stomach, the liver, (the right lobe of which, except in Falconiformes, is always considerably larger than the left lobe), and last but not least by pressure exerted just in that region by the vena cava posterior, which is situated along the right side of the vertebral column. Kumerloeve also suggests that the reduction of the right ovary preceded the reduction of the right oviduct during evolution.

Without question paired ovaries have been found most commonly in the Order Falconiformes. And in most cases it has been recorded that the right ovary was the smaller of the two, although it often appeared to be functional. Stanley and Witschi (1940) state that the largest right ovaries occur with the true hawks (subfamily Accipitrinae), "whereas vultures and buzzards have the smallest right ovaries; the falcons holding an intermediate position". Stieve (1924) reports that in 50% of the cases in which double ovaries were found in Sparrow Hawks (Accipiter nisus), the right ovaries were smaller than the left, whereas in the other 50 % the ovaries were of equal size. Right ovaries larger than left ovaries were reported by Brodkorb (1928) with Circus c. hudsonicus and by Gunn (1912) with Accipiter nisus and Falco tinnunculus. As for the positioning of paired ovaries within the body cavity, Gunn (1912) points out that with Falconiformes the two ovaries are arranged (almost without exception) symmetrically and parallel to each other. With other birds Gunn states "the arrangement of the ovaries is more irregular and uncertain. They are seldom symmetrically placed, the general tendency being for the right ovary to move downwards and to the left, so that the whole of the left ovary and the greater part of the right are contained in the left half of the body cavity, one ovary more or less overlapping the other".

Double oviducts have not been found as often as double ovaries. Here again, they seem to predominate in the order Falconiformes, but for example have been found also in Ciconiiformes (Ciconia ciconia), in Anseriformes, Ralliformes, Columbiformes and Psittaciformes. Unfortunately not all authors who have found right oviducts reported if these were complete (i. e. possibly functional), or were only vestigial. Nevertheless, Gunn (1912) reports having found complete and seemingly functional right oviducts in Accipter nisus and in Falco tinnunculus. In particular he mentions one Sparrow Hawk in which "the right oviduct was double the width of the left and had the appearance of having recently passed eggs". In most cases, however, the right oviducts, if present, are only rudimentary, and the presence or absence of the vestigial right oviduct (with Hawks) is not directly correlated with larger or smaller size of the right ovary (Stanley and Witschi, 1940).

Anatomical proof of a fully functional right ovary, has been presented in only two cases. Stieve (1924) reports having obtained a female Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) which was shot while incubating a clutch of 3 fresh eggs. On dissection he found that the bird had two ovaries, but only one oviduct. In addition to several larger ovules showing signs of regression, in both ovaries, he found two ruptured follicles on the left ovary and one ruptured follicle on the right ovary. This indicates that two of the 3 eggs of the clutch originated from the left ovary, whereas the third egg originated from the right ovary. As there was only one (the left) oviduct present, the author assumed that the ovum, following ovulation from the right ovary, had to wander over (Überwanderung) to the left side of the body to meet the oviduct.

In the second case White (1969) reports having dissected a female Peregrine (Falco peregrinus) obtained from Alaska, in which he found that "the left ovary was markedly atrophied and appeared never to have been functional. The right ovary had 5 enlarged follicles about 25 mm in diameter and two visible ovarian scars from which follicles had ruptured". From his findings, White concludes that "although two ovaries may be present, only one appears to be functional in egg production in any one season or perhaps throughout the life of the bird".

A most unusual case of paired reproductive organs was reported by Chappellier (1914). A domestic duck, which laid two eggs daily, was found to have double ovaries and double oviducts.

Table I has been drawn up from the literature available to the writer. It contains all orders and species of birds in which paired ovaries and paired oviducts have been found. This table shows that paired ovaries have been found in 86 species of birds belonging to 16 Orders, and paired oviducts have been found in 33 species belonging to 12 Orders. As mentioned above, paired ovaries and oviducts predominate in the Order Falconiformes (45 species) but have also been found in many additional species. The seemingly less frequent occurrences of double ovaries in other orders of birds might be due partly to the fact that they are not usually sought (Gunn 1912). However, as paired ovaries are well known in Raptors, they are probably automatically looked for in this order during routine dissections. If normal sexing routine for all birds included examination of the right half of the body cavity in addition to the usual examination of the left side only, more occurrences of paired ovaries and oviducts might possibly be found.

Summary

The ratite order Apterygiformes is the only group of birds in which:

1 - Paired ovaries occur consistently without known exceptions.

2 - The right ovary (as well as the left) is usually functional.

3 - Successful ovulation from the right ovary (as well as the left) is a normal occurrence.

4 - If more than one egg is laid during tho same season, ovulation occurs alternately from the two ovaries.

In addition the following points have also been established:

5 - In the North Island Kiwi irregular time intervals between egg laying within one clutch are apparently owing to the widely differing stages of development of the succeeding follicles at the time of laying of the preceding egg.

6 - Only the left oviduct is functional in Kiwis and vestigial right oviducts occur only rarely.

7 - From the evidence obtained during this study on Kiwis it appears that the reduction of the right oviduct in birds might well have preceded the reduction of the right ovary during their evolutionary history.

8 - Despite textbook statements paired ovaries in birds have been recorded in individual birds of at least 86 species belonging to 16 different orders and paired oviducts in birds have now been recorded in individuals of at least 34 species belonging to 13 different orders.

9 - Although it has long been known that paired ovaries occurred commonly but irregularly in some members of the carinate order Falconiformes, species of this group form only 52% of the total number of bird species in which paired ovaries have now been recorded. If normal sexing routine in birds included the examination of the right side of the body cavity in addition to the usual examination of the left side, additional species (and additional orders) with paired ovaries might well be found.