Lessico

Johann Stumpf

Storico svizzero (Bruchsal 1500 - Zurigo 1576). Entrato nell'ordine dei giovanniti, divenne parroco e priore di Bubikon (Zurigo), poi aderì alle posizioni di Zwingli. Dopo lunghe ricerche scrisse una storia della Svizzera contenente tutte le leggende sull'origine della confederazione (Gemeiner loblicher Eydgenossenschaft Stetten, Landen und Voelkeren chronikwirdiger Thaaten Beschreibung, 1548), opera della quale egli stesso fece poi un estratto (Schwytzer Chronik, 1554) e in cui è notevole il tentativo di inserire la storia locale in quella europea, con particolari riferimenti alle vicende francesi e tedesche. Compose inoltre un'importante storia del Concilio di Costanza (Des grossen gemeinen Conciliums zu Constanz Beschreibung, 1541).

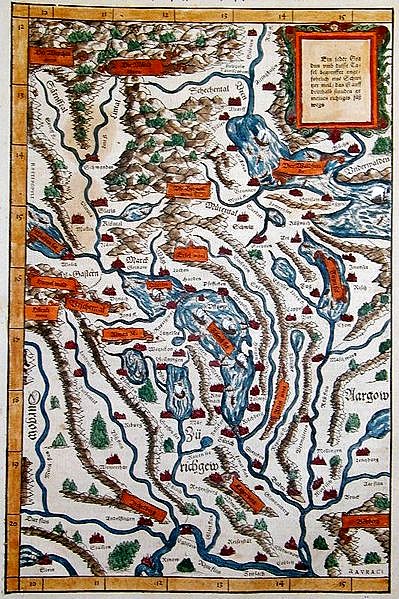

The Swiss region around Zurich

Johann Stumpf (1500-1576) was an early writer on the history and topography of Switzerland. He was born at Bruchsal (near Karlsruhe), and was educated there and at Strasbourg and Heidelberg. In 1520 he became a cleric or chaplain in the order of the Knights Hospitaller. He was sent in 1521 to the preceptory of that order at Freiburg in Breisgau, ordained a priest at Basel, and in 1522 was placed in charge of the preceptory at Bubikon (north of Rapperswil, in the canton of Zürich). However, Stumpf went over to the Protestants, was present at the great Disputation in Bern (1528), and took part in the first Kappel War (1529).

In 1529 he married the first of his four wives, a daughter of Heinrich Brennwald, who wrote a work (still in manuscripts) on Swiss history, and stimulated his son-in-law to undertake historical studies. Stumpf made wide researches, with this object, for many years, and undertook also several journeys, of which that in 1544 to Engelberg and through the Valais seems to be the most important, perhaps because his original diary has been preserved to us. The fruit of his labours (completed at the end of 1546) was published in 1548 at Zürich in a huge folio of 934 pages (with many fine wood engravings, coats of arms, maps, &c.), under the title of Gemeiner loblicher Eydgenossenschaft Stetten, Landen und Voelkeren chronikwirdiger Thaaten Beschreibung (an extract from it was published in 1554, under the name of Schwytzer Chronik, while new and greatly enlarged editions of the original work were issued in 1586 and 1606). The woodcuts are best in the first edition, and it remained till Scheuchzer's day (early 18th century) the chief authority on its subject.

The

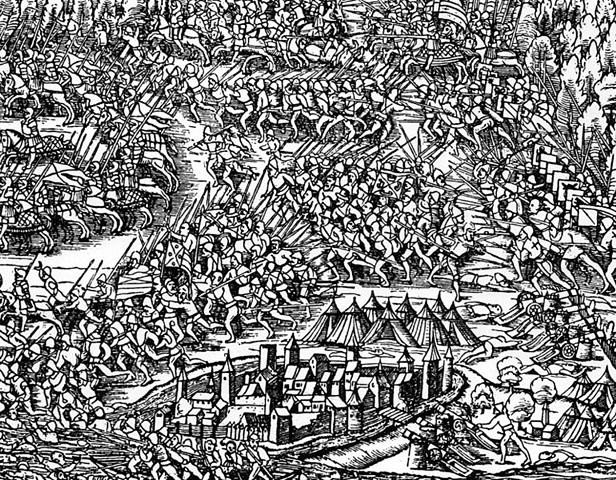

battle of Morat![]() ,

part of an engraving from the Stumpf Chronik.

,

part of an engraving from the Stumpf Chronik.

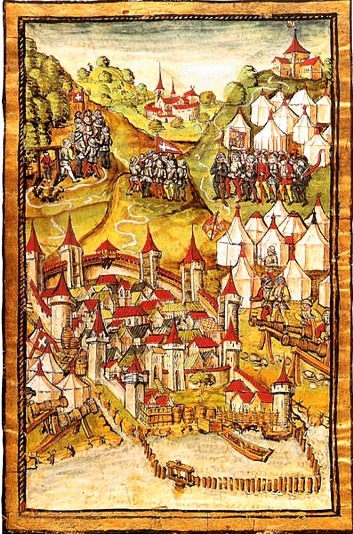

The Swiss town of Zug

When he converted to Protestantism, Stumpf had carried over with him most of his parishioners, whom he continued to care for, as the Protestant pastor at Bubikon, till 1543. He then became pastor of Stammheim (same canton) until 1561, when he retired to Zürich (of which he had been made a burgher in 1548), where he lived in retirement till his death in 1576.

Stumpf also published a monograph (very remarkable for the date) about Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor (1556) and a set of laudatory verses (Lobspruche) about each of the thirteen Swiss cantons.

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Part

of Burgundian Wars

The battle of Morat by Diebold Schilling

Date June

22, 1476

Location Near Murten, Canton of Berne

Result Swiss victory

Combatants

Duchy of Burgundy Swiss Confederation

Commanders

Duke Charles, Jacques, Duke of Savoy Hans von Hallwyl, Hans Waldmann, Adrian

von Bubenberg,René II, Duke of Lorraine,

Strength

c. 20,000 c. 25,000

The Battle of Morat was a battle in the Burgundian Wars fought June 22, 1476 between Charles I, Duke of Burgundy and a Swiss army at Murten (French: Morat), about 30 kilometers from Bern.

Background

Stung by his embarrassing defeat by the Swiss Confederation at Grandson in March 1476, Charles, Duke of Burgundy rebuilt his routed but otherwise mainly intact army at Lausanne. By the end of May he once again felt ready to march against the Confederates to recover his territories and fortifications in the Pays de Vaud (North of Geneva) then march on and attack the city of Berne, his greatest enemy among the cantons.

His first objective was the strategic lakeside town of Murten, set on the eastern shore of Lake Morat. On June 11, 1476 the Burgundians commenced the siege of the well-prepared town, whose forces were commanded by the Bernese general Adrian von Bubenberg. An initial assault was repulsed by a heavy barrage of fire from light guns mounted on the walls, but two great bombards used by the Burgundians were slowly reducing the walls to rubble. By June 19 the Confederate muster was near complete at their camp behind the River Saane. Only a contingent of some 4,000 men from Zürich had yet to arrive and these were not expected until June 22.

Charles in the meantime had been kept reasonably well informed of the approach of the Confederate army, though he did nothing to hinder their approach. This is not to say that he was unprepared for the arrival of the Swiss, indeed in typical fashion Charles had prepared an elaborate plan to meet the enemy on ground of his choosing where he thought they would approach from some 2 km from Murten. The terrain around Murten is quite hilly and he had chosen to rest his left flank artillery on a steeply sloped gorge cut by the Burggraben stream. In the centre, behind an elaborate ditch and palisade entrenchment known as the Grunhag, stood the bulk of Charles’ infantry and artillery not engaged in besieging Murten itself. These were to fight the Confederation pike and halberd blocks to a halt while on the right the massed Gendarmes would then flank the frontally engaged Swiss, thus creating a killing ground from which there was no escape.

The Battle

Saturday, June 22, 1476 dawned stormy and dark. Charles had not seen fit to scout beyond the River Saane to see what held the Swiss back, but there was a notion round the Burgundian camp that this was to be the day of battle. The Burgundians stood to at dawn in expectation of the enemy and remained drawn up for battle all morning in the pouring rain, but no horde of enemy appeared, and at noon Charles stood down most of his men, leaving the Grunhag manned by 2,000 infantry and 1,200 horse. Retiring to their camp the Burgundians sought shelter from the rain, besides it was also a payday and many sought their midday meal after a soaking that morning. It was then that the Confederate Vanguard of some 6,000 skirmishers and all the 1,200 cavalry present erupted out of Birchenwald Woods to the west of Murten, exactly where Charles had predicted they would appear.

Behind the

Vanguard came the main body of pike, the Gewalthut (Centre). This was some

10,000–12,000 strong and was formed in a huge wedge with the cantonial

standards in the centre, flanked by halberds and an outer ring of pikemen. The

Rearguard of 6,000–8,000 more closely packed pike and halberdiers followed

the Gewalthut towards the now sparsely manned Grunhag.

As the Swiss charged downhill into the Burgundian position the artillery

managed to fire a few salvoes, killing or maiming several hundred of the

overeager Lorrainers. Against the odds the defenders in the Grunhag held the

Swiss for some time before a contingent of Swiss found a way through the left

flank of the defences near the Burggraben and turned the whole position. The

Swiss formed up quickly beyond it and advanced towards Murten and the

besieger’s camp.

In the Burgundian camp all hell was let loose once the Swiss were sighted as men rushed to reform and prepare for battle. In the Ducal tent on top of the Bois Du Domingue, a hill overlooking Murten, Charles was quickly armed by his retainers before rushing on horseback to try and co-ordinate the defence of the camp. But as fast as any unit was formed and moved forward against the Swiss, it was swept aside as various uncoordinated attacks were made against the still compact Confederate battle formations. There was some resistance from the squadrons of the Ducal household who routed the Lorrainers, including René II, Duke of Lorraine, who was saved only by the arrival of the pikes, against which the Gendarmes could only retire, unable to make any impression against them.

Charles managed to muster enough English archers to form a last line of defence before the camp, but these were routed before a bow could be bent, their commander shot by a Swiss skirmisher. Then it was every man for himself as Charles ordered the army to fall back which was interpreted as a retreat, which in turn became a rout as all organized resistance ended.

For some three miles along the lakeside many Burgundians died that day in the rout. The Italian division of some 4,000–6,000 men besieging the southern part of Murten probably suffered the worst fate: cut off by the Swiss rearguard and attacked by a sally from the town, they were hunted down along the shore and driven into the lake. As promised, no quarter was granted.

More fortunate was the Savoyard division under Jacques, Duke of Savoy which was posted in the northern half of the Murten siege works. Forming up and abandoning all their baggage they retreated east round the lake and eventually made good their escape to Romont (one of Jacques' lesser titles was count of Romont).

Byron in Canto III of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage has these words on the battle:

63

But ere these matchless heights I dare to scan,

There is a spot should not be pass'd in vain,--

Morat! the proud, the patriot field! where man

May gaze on ghastly trophies of the slain,

Nor blush for those who conquered on that plain;

Here Burgundy bequeath'd his tombless host,

A bony heap, through ages to remain,

Themselves their monument;--the Stygian coast

Unsepulchred they roam'd, and shriek'd each wandering ghost.

64

While Waterloo with Cannae's carnage vies,

Morat and Marathon twin names shall stand;

They were true Glory's stainless victories,

Won by the unambitious heart and hand

Of a proud, brotherly, and civic band,

All unbought champions in no princely cause

Of vice-entail'd Corruption; they no land

Doom'd to bewail the blasphemy of laws

Making kings' rights divine, by some Draconic clause.

Aftermath

Charles’ dream of revenge against the Confederates ended that day. Although he would doggedly struggle for another six months against his foes, his defeat at Murten really spelled the beginning of the end for the Duchy of Burgundy, much to the delight of the Duke’s enemies.

Charles escaped to Morges, and then to Pontarlier, where he stayed for months, reportedly in a deep depression. He later returned to the battlefield at the Battle of Nancy, where he was killed.