Lessico

Sulpicio Severo

Sulpicius Severus

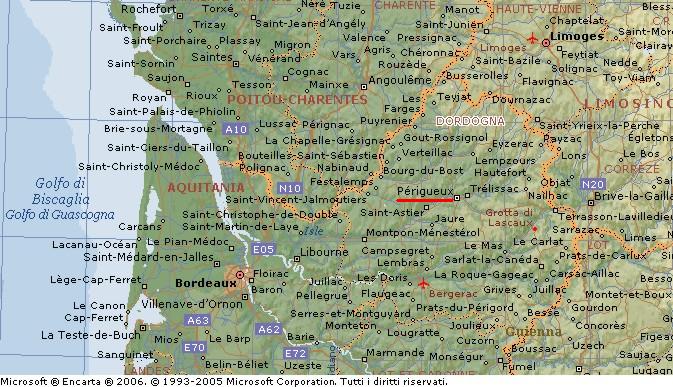

Scrittore ecclesiastico nato in Aquitania circa nel 360, morto a Primuliacum nel 420 circa. Dopo la morte della moglie si ritirò a vita monastica presso Primuliacum (forse l’odierna Primillac nei pressi di Périgueux, capoluogo del dipartimento di Dordogna nel Périgord).

Ebbe un'eccellente

educazione, studiando giurisprudenza e divenne celebre quale eloquente

avvocato. Il suo matrimonio con la figlia di una ricca famiglia di consoli

sembrò condurlo alla felicità terrena. Ma perduta la moglie da una morte

prematura, subito dopo il 390, Severo rinunciò alla sua brillante carriera e

seguì il fratello Paolino per ritirarsi in monastero. Questo improvviso

cambiamento della sua vita trovò la disapprovazione del padre, ma trovò

incoraggiamento dalla suocera. Diventò amico intimo ed entusiasta discepolo

di Martino di Tours![]() e di San Paolino di Nola

(vescovo, poeta e santo, Bordeaux 353-Nola 431).

e di San Paolino di Nola

(vescovo, poeta e santo, Bordeaux 353-Nola 431).

Visse vicino a Eauze, a

Tolosa e a Luz nella Francia del sud. Gennadio testimonia sulla sua

ordinazione a prete, ma non esiste alcun dettaglio circa la sua attività

sacerdotale. Secondo lo stesso Gennadio, Severo si accostò verso la fine

della sua vita al Pelagianesimo (dottrina teologica formulata da Pelagio -

monaco inglese e scrittore religioso ca. 354-ca. 427 - affermante la

sostanziale sanità morale della natura umana anche dopo il peccato originale)

ma presto, scoprendo il suo errore, si impose il silenzio fino alla fine dei

suoi giorni per espiare la sua imprudenza. È autore di Chronicorum Libri

duo (dalla creazione al 400 dC) importanti per la storia del

priscillanesimo o priscillianismo![]() in Gallia, di scritti agiografici (Vita Martini, Dialogi), modelli di

stile classico sull’esempio di Sallustio e di Tacito, largamente seguiti

dall’agiografia medievale.

in Gallia, di scritti agiografici (Vita Martini, Dialogi), modelli di

stile classico sull’esempio di Sallustio e di Tacito, largamente seguiti

dall’agiografia medievale.

Christian writer, was a native of Aquitania (c. 363 - c. 420-425). He was imbued with the culture of his time and of his country, which was then the only true home of Latin letters and learning. Almost all that we know of Severus life comes from a few allusions in his own writings, and some passages in the letters of his friend Paulinus, bishop of Nola. In his early days he was famous as a pleader, and his knowledge of Roman law is reflected in parts of his writings. He married a wealthy lady belonging to a consular family, who died young, leaving him no children.

At this time Severus came under the powerful influence of St Martin, bishop of Tours (Sabaria, Pannonia, 316 o 317-Candes, Touraine, 397), by whom he was led to devote his wealth to the Christian poor, and his own powers to a life of good works and meditation. To use the words of his friend Paulinus, he broke with his father, followed Christ, and set the teachings of the fishermen far above all his Tullian learning. He rose to no higher rank in the church than that of presbyter. He is said to have been led away in his old age by Pelagianism, but to have repented and inflicted long-enduring penance on himself.

His time was passed chiefly in the neighborhood of Toulouse, and such literary efforts as he permitted to himself were made in the interests of Christianity. In many respects no two men could be more unlike than Severus, the scholar and orator, well versed in the ways of the world, and Martin, the rough Pannonian bishop, ignorant, suspicious of culture, champion of the monastic life, seer and worker of miracles. Yet the spirit of the rugged saint subdued that of the polished scholar, and the works of Severus are only important because they reflect the ideas, influence and aspirations of Martin, the foremost ecclesiastic of Gaul.

The chief work of Severus is the Chronica (c. 403) - The Chronicle - Chronicorum Libri duo or Historia sacra -, a summary of sacred history from the beginning of the world to his own times, with the omission of the events recorded in the Gospels and the Acts, lest the form of his brief work should detract from the honor due to those events. The book was a text-book, and was used as such in the schools of Europe for about a century and a half after the editio princeps was published by Flacius Illyricus in 1556. Severus nowhere clearly points to the class of readers for whom his book is designed. He disclaims the intention of making his work a substitute for the actual narrative contained in the Bible. Worldly historians had been used by him, he says, to make clear the dates and the connection of events and for supplementing the sacred sources, and with the intent at once to instruct the unlearned and to convince the learned.

Probably the unlearned are the mass of Christians and the learned are the cultivated Christians and pagans alike, to whom the rude language of the sacred texts, whether in Greek or Latin, would be distasteful. The literary structure of the narrative shows that Severus had in his mind principally readers on the same level of culture with himself. He was anxious to show that sacred history might be presented in a form which lovers of Sallust and Tacitus could appreciate and enjoy. The style is lucid and almost classical. Though phrases and even sentences from many classical authors are in woven here and there, the narrative flows easily, with no trace of the jolts and jerks which offend us in almost every line of an imitator of the classics like Sidonius. It is free from useless digressions. In order that his work might fairly stand beside that of the old Latin writers, Severus ignored the allegorical methods of interpreting sacred history to which the heretics and the orthodox of his age were wedded.

After the Chronica the chief work of Severus is his Life of Martin - Vita Martini Turonensis Episcopi -, a contribution to popular Christian literature which did much to establish the great reputation which that wonder-working saint maintained throughout the middle ages. The book is not properly a biography, but a catalogue of miracles, told in all the simplicity of absolute belief. The power to work miraculous signs is assumed to be in direct proportion to holiness, and is by Severus valued merely as an evidence of holiness, which he is persuaded can only be attained through a life of isolation from the world.

In the first of his Dialogues (fair models of Cicero), Severus puts into the mouth of an interlocutor (Posthumianus) a pleasing description of the life of coenobites and solitaries in the deserts bordering on Egypt. The main evidence of the virtue attained by them lies in the voluntary subjection to them of the savage beasts among which they lived. But Severus was no indiscriminating adherent of monasticism. The same dialogue shows him to be alive to its dangers and defects.

The second dialogue is a large appendix to the Life of Martin, and really supplies more information of his life as bishop and of his views than the work which bears the title Vita S. Martini. The two dialogues occasionall make interesting references to personages of the epoch.

In Dia I, cc. 6, 7, we have a vivid picture of the controversies which raged at Alexandria over the works of Origen. The judgment of Severus himself is no doubt that which he puts in the mouth of his interlocutor Posthumianus: I am astonished that one and the same man could have so far differed from himself that in the approved portion of his works he has no equal since the apostles, while in that portion for which he is justly blamed it is proved that no man has committed more unseemly errors.

Three Epistles on the death of Martin (ad Eusebium, ad Aurelium diaconum, ad Bassulam) complete the list of Severus genuine works. Other letters (to his sister), on the love of God and the renunciation of the world, have not survived.

http://12.1911encyclopedia.org

Priscilliano (ca. 345 - ca. 385), un nobile ed erudito spagnolo, stabilì, nel 385, il non invidiabile primato di essere stato il primo eretico messo a morte dalla Chiesa Cristiana, anche se per ordine dell'imperatore usurpatore Massimo Magno Clemente (383-388).

Priscilliano, nato probabilmente nel 345, imparò le dottrine gnostiche manichee da un certo Marco, un egiziano di Memphis, e sviluppò un movimento ascetico molto popolare, al tempo, in Spagna.

Il movimento attirò le simpatie di due vescovi cattolici, Istanzio e Salviano e di uno studioso di retorica, Elpidio, ma anche le preoccupazioni di tre vescovi ortodossi, Igino di Cordova, Idacio di Emeritu e Itacio di Ossanova (il più accanito anti-priscillianista), che convinsero i vescovi spagnoli a convocare un sinodo nel 380 a Saragozza, dove i priscillianisti furono scomunicati. Nonostante le condanne del suo movimento, Priscilliano, diventato dapprima sacerdote, fu nominato vescovo d'Avila nel 380 ca., ma poco dopo fu esiliato, nel 381, dall'imperatore Graziano (375-383).

In Italia la sua condanna all'esilio fu condonata e Priscilliano rientrò in Spagna, aumentando il suo seguito e obbligando, a sua volta, Itacio all'esilio. Quest'ultimo pensò di ricorrere all'imperatore, ma, nel 383, il legittimo regnante Graziano era stato assassinato dall'usurpatore Massimo Magno Clemente, al quale, comunque, ricorse Itacio.

Massimo convocò il sinodo di Bordeaux nel 384, dove Itacio riuscì a far condannare il vescovo priscillianista Istanzio, ma Priscilliano stesso si appellò all'imperatore recandosi a Treviri: ancora una volta Itacio attaccò Priscilliano con una tale ferocia che San Martino di Tours (ca.316-397), presente al processo, intervenne, lamentando che una causa religiosa fosse finita davanti a un tribunale civile. San Martino cercò, inoltre, di convincere Massimo a non applicare la pena di morte in caso di condanna, ma quando il santo lasciò la città, l'imperatore fece decapitare, nel 385, Priscilliano e i suoi seguaci, sotto l'accusa di magia.

L'esecuzione fu censurata dal mondo cattolico da Papa San Siricio (384-399) fino a Sant'Ambrogio, e l'ondata d'indignazione che ne seguì portò, perlomeno, alla definitiva deposizione e allontanamento di Itacio e Idacio. Oltretutto, la condanna a morte di Priscilliano non fece che crescere la popolarità del suo movimento, condannato nuovamente, ma inutilmente, dal sinodo di Toledo del 400.

15 anni più tardi, nel 415, il prete spagnolo Paolo Orosio, allievo di Sant'Agostino, sentì la necessità di rivolgersi al suo maestro per chiedere il suo aiuto nella lotta contro il priscillianismo. In seguito, nel 427, su sollecitazione del diacono Quodvultdeus, Agostino ne scrisse nella sua opera Sulle eresie (De haeresibus). Tuttavia né quest'episodio né vari concili nel V secolo riuscirono a debellare il movimento, che si poté definire scomparso solo dopo il Sinodo di Braga del 563.

La dottrina di Priscilliano era una complessa miscela di manicheismo dualista, docetismo e sabellianismo. Dal manicheismo dualista Priscilliano predicava che il corpo era opera del demonio, principio del male e delle tenebre, mentre l'anima era fatta della stessa sostanza di Dio e che avrebbe potuto vincere contro il regno delle tenebre, ma che era stata intrappolata nel corpo come punizione per i suoi peccati. Perciò l'uomo, secondo Priscilliano, poteva redimersi solo con una condotta veramente virtuosa. Dal docetismo Priscilliano aveva preso il concetto che Cristo fosse una emanazione divina, negando la sua incarnazione e il conseguente dogma della resurrezione. Dal sabellianismo Priscilliano aveva attinto la negazione della pre-esistenza di Cristo prima della Sua nascita e della Sua natura umana. Inoltre, il Padre e il Figlio non erano che due modi di presentarsi della stessa Persona divina.

Dal punto di vista comportamentale i priscillianisti erano fortemente critici nei confronti di una crescente esteriorità della Chiesa Cristiana: erano molto ascetici, digiunavano di domenica e a Natale, e, poiché spesso erano alquanto facoltosi, essi vendevano tutti i loro beni per aiutare i poveri. Inoltre erano soliti portare a casa l'ostia data durante l'Eucaristia in chiesa per prenderla durante cerimonie private di preghiera, quasi come forma di rifiuto della Chiesa ufficiale.

www.eresie.it

Priscillian, bishop of Ávila (died 385), a theologian from Roman Gallaecia (in the Iberian Peninsula), was the first person in the history of Christianity to be executed for heresy (though the civil charges were for the practice of magic). He founded an ascetic group that, in spite of persecution, continued to subsist in Hispania and Gaul until the later 6th century. Tractates by Priscillian and close followers, which had seemed certainly lost, were recovered in 1885 and published in 1889.

Priscillian's career

The principal and almost contemporary source for the career of Priscillian is the Gallic chronicler Sulpicius Severus, who characterized him (Chronica II.46) as noble and rich, a layman who had devoted his life to study, vain of his classical pagan education, already being looked on with misgivings (see Gregory of Tours). He was an ascetic mystic and regarded the Christian life as continual intercourse with God. His favourite idea was Saint Paul`s "Know ye not that ye are the temple of God?" (I Corinthians 6:19) and he argued that to make himself a fit habitation for the divine a man must, besides holding the Catholic faith and doing works of love, renounce marriage and earthly honour, and practise a hard asceticism. It was on the question of continence in, if not renunciation of, marriage, that he came into conflict with the authorities, and his influence among growing numbers of followers threatened the authority of the church when the bishops Instantius and Salvian were won over by his eloquence and his severely ascetic example.

His notable opponents in Hispania were Hyginus, bishop of Cordoba, and Hydatius, bishop of Mérida. Their complaint to Pope Damasus I (also from Hispania) resulted in a synod held at Saragossa in 380, in the absence of Priscillian or any of his followers. The canons issued by the synod shed light on Priscillian's practices, by condemnation. That is, much of what was forbidden was condemned because the Priscillians were practicing it. Women were forbidden to join with men during the time of prayer; fasting on Sunday was condemned; no one was to retreat at home or in the mountains during Lent; the Eucharist was to be taken in church and not brought home; excommunicated persons were not to be sheltered by bishops; a cleric was forbidden to become a monk on the motivation of a more perfect life; no one was to assume the title "doctor" (Latin for teacher); women were not to be accounted "virgins" until they had reached the age of forty.

Through the exertions of Hydatius of Emerita, the leading Priscillianists, who had failed to appear before the synod of Hispanic and Aquitanian bishops to which they had been summoned, were excommunicated at Saragossa in October 380, according to Sulpicius, a conclusion that was emphatically denied in a letter to Damasus, Liber ad Damasum episcopum (McKenna, note 14).

Among the more prominent of Priscillian's friends were two bishops, Instantius and Salvianus; Hyginus of Cordova also joined the party. After a Priscillianist delegation to Hydatius was turned away, they appointed Priscillian bishop of Ávila, and the orthodox party found it necessary to appeal to the emperor Gratianus, who issued an edict threatening the sectarian leaders with banishment. Consequently, the three bishops, Instantius, Salvianus and Priscillian, went in person to Rome, to present their case before Damasus. But neither the Pope nor Ambrose, bishop of Milan, granted them an audience. Salvianus died in Rome, but through the intervention of Macedonius, the imperial magister officiorum and an enemy of Ambrose, they succeeded in procuring the withdrawal of Gratianus' edict, and the attempted arrest of Ithacius of Ossonuba.

On the murder of Emperor Gratianus in Lyon and the accession, at Trier (Trèves, in Germany) at least, of the usurper Magnus Maximus (383), Ithacius fled to Trier, and in consequence of his representations a new synod was held (384) at Bordeaux, where Instantius was deposed. Priscillian appealed to the emperor, with the unexpected result that, with six of his companions, he was beheaded at Trier in 385, the first Christian heretics to be put to death by Christians. This act had the approval of the synod which met at Trier in the same year, but Ambrose of Milan, Pope Siricius and Martin of Tours protested against Priscillian's execution, largely on the jurisdictional grounds that an ecclesiastical case should not be decided by a civil tribunal, and worked to reduce the persecution.

Priscillian's contemporary following

Priscillian and his sympathizers included many women, who were welcomed as equals of men. They were organised into bands of spirituales and abstinentes. This insistence on celibacy explains the charge of Manichaeism some levelled against Priscillian (even Jerome, for his talk of the sordes nuptiarum, had been similarly accused, and to escape popular indignation had retired to Bethlehem). To this charge was added the accusation of magic and licentious orgies (a particularly preposterous charge, given the nature of Priscillian's doctrines).

Continued Priscillianism

The heresy, notwithstanding the severe measures taken against it, continued to spread in Gaul as well as in Hispania; in 412 Lazarus, bishop of Aix-en-Provence, and Herod, bishop of Arles, were expelled from their sees on a charge of Manichaeism. Proculus, the metropolitan of Marseille, and the metropolitans of Vienne and Narbonensis Secunda were also followers of the rigorist tradition for which Priscillian had died.

Something was done for its repression by a synod held by Turibius of Astorga in 446, and by that of Toledo in 447; as an openly professed creed it had to be declared heretical once more by the second synod of Braga in 563, a sign that Priscillianist asceticism was still strong long after his execution. "The official church," says F. C. Conybeare, "had to respect the ascetic spirit to the extent of enjoining celibacy upon its priests, and of recognizing, or rather immuring, such of the laity as desired to live out the old ascetic ideal. But the official teaching of Rome would not allow it to be the ideal and duty of every Christian. Priscillian perished for insisting that it was such".

The long prevalent estimation of Priscillian as a heretic and Manichaean rested upon Augustine, Turibius of Astorga, Leo the Great and Orosius (who quotes a fragment of a letter of Priscillian's), although at the Council of Toledo in 400, fifteen years after Priscillian's death, when his case was reviewed, the most serious charge that could be brought was the error of language involved in a misrendering of the word innascibilis ("unbegettable").

It is not always easy to separate the genuine assertions of Priscillian himself from those ascribed to him by his enemies, nor from the later developments taken by groups who were labelled 'Priscillianist'. Priscillian casts a long shadow in the north of Hispania and the south of Gaul, where mystic asceticism has repeatedly been carried to extremes that the political mainstream has denounced as 'heretical'.

Priscillian was long honored as a martyr, not heretic, especially in Gallaecia (modern Galicia and northern Portugal), where his body was reverentially returned from Trier. Some claim that the remains found in the 8th century at the site rededicated to Saint James the Great — Santiago de Compostela — which even today are a place of the pilgrimage belong not to the apostle James but to Priscillian.

Writings and rediscovery

Some writings by Priscillian were accounted orthodox and were not burned. For instance he divided the Pauline epistles (including the Epistle to the Hebrews) into a series of texts on their theological points and wrote an introduction to each section. These "canons" survived in a form edited by Peregrinus. They contain a strong call to a life of personal piety and asceticism, including celibacy and abstinence from meat and wine. The charismatic gifts of all believers are equally affirmed. Study of scripture is urged. Priscillian placed considerable weight on the deuterocanonical books of the Bible, not as being inspired but as helpful in discerning truth and error; however several of the books were considered to be genuine and inspired.

It was long thought that all the writings of the "heretic" himself had perished, but in 1885, Georg Schepss discovered at the University of Würzburg eleven genuine tracts, published in the Vienna Corpus 1886. Though they bear Priscillian's name, four describing Priscillian's trial appear to have been written by a close follower.

According to Raymond Brown's introduction of his edition Epistle of John, the source of the Comma Johanneum, a brief interpolation in the First Epistle of John, known since the fourth century, appears to be the Latin Liber Apologeticus by Priscillian.

The modern assessment of Priscillian is summed up in Cambridge professor Henry Chadwick's Priscillian of Avila: The Occult and the Charismatic in the Early Church, (Oxford University Press) 1975.

Fletcher, Richard A., "St. James' Catapult: The Life and Times of Diego Gelmirez", Chapter 1 and passim: Galicia, online at http://libro.uca.edu/sjc/sjc.htm which offers a historical and geographical background to the building of the cathedral in Compostela, and Burras, Virginia, The Making of a Heretic, U. of California Press, 1995

McKenna, Stephen, "Priscillianism and Pagan Survivals in Spain" in Paganism and Pagan Survivals in Spain up to the Fall of the Visigothic Kingdom on-line The present account depends on this thoroughly cited chapter.