Marcello Malpighi

De formatione pulli in ovo

The formation of the chick in the egg

Transcribed

by Fernando Civardi![]()

translated by Elio Corti

translation reviewed by Roberto Ricciardi![]()

English text reviewed by Elly Vogelaar![]()

September 2010

The

Latin text is drawn from

Marcelli Malpighii Opera omnia

Londini – apud Robertum Scott MDCLXXXVI

but

because of some mistakes contained in it

it has been emended with the following source

Marcelli

Malpighii Opera omnia

Lugduni Batavorum – apud Petrum Vander MDCLXXXVII

The

footnotes mostly come from

Opere scelte di Marcello Malpighi a cura di Luigi Belloni - Torino UTET 1967

The

asterisk indicates that the item is present in lexicon![]()

|

[1]

DE

FORMATIONE PULLI IN OVO. MAGNAE

SOCIETATI REGIAE ANGLICANAE |

THE

FORMATION OF THE CHICK IN THE EGG Marcello

Malpighi very cordially greets |

|

Solent

in excitandis machinis praevio operis apparatu singulas efformare

partes, ita ut separata prius pateant ea, quae postmodum redigi debent

in compagem. Hoc in Naturae operibus plures eiusdem Mystae, circa

Animalium indaginem soliciti, accidere sperabant. Corporis etenim

implicatam structuram cum difficillimum sit resolvere, disparatas in

primordiis singulorum productiones intueri iuvabat. Sed vereor,

mortalium vitam incertis nimium finibus claudi, et aeque obscurum esse

carcerem, ac metam.

Quare, sicut Mors, monente Tullio[1],

nec ad vivos, nec ad mortuos pertinet; ita quid tale in primaevo Animalium initio

accidere censeo: dum enim ab Ovo

animalium solicite perquirimus productionem, in Ovo ipso iam fere animal miramur excitatum, ita ut irritus

noster labor reddatur: Nam primum ortum non assequuti, emergentem

successive partium manifestationem expectare cogimur. |

When

machines are built, before starting their assemblage it is usual to

make the single components, so that first are separately seen the

pieces that subsequently have to be joined. Quite a lot of initiates

to the mysteries of nature, very interested in investigating the

animals, hoped that this happened in the works of nature. In fact,

being very difficult to disentangle the tangled structure of the body,

it appeared useful to attentively investigate from the beginning the

separate formation of each part. But I fear that the life of the

mortals is comprised within too much uncertain boundaries and that the

beginning and the end are so much dark. Which is why, as Cicero* says,

like the death is not concerning neither to living nor to dead people,

I think that in the same manner something similar happens in the

initial stages of animals' life: in fact, studying with care the

formation of the animals from the egg, in the egg itself we observe

the animal as if it had been created, so that our labour is frustrated.

In fact, not having understood the beginning of the birth, we are

forced to wait for the following appearing of the parts. |

|

In

hac quidem perquisitione insudarunt quamplures; inter quos immortalis

vester eminet Harveus, cuius

absolutissimae observationes adhuc ita orbem erudiunt, ut meos

praesertim labores veluti supervacaneos refellant. Quoniam tamen,

eodem afferente[2],

latent plerumque veluti in alta

nocte prima naturae stamina, et subtilitate sua non minus ingenii,

quam oculorum aciem eludunt, tamque varia Naturae vis, incerta

quasi maturitate, modo accelerat, modo differt emergentiam foetus;

ideo rudia quaedam Observationum inchoamenta ex incubatorum Ovorum [2]

lustratione, quam adhuc saepius repetendam propono, me Vobis,

Sodales doctissimi, communicare patiemini, ut si Naturae et magnis

vestris Mentibus consona deprehenderitis, subsequentium annorum

curriculo ea iterum confirmem, consimilium mediatione adaugeam,

novisque, prout tenuitati meae sperare competit, auctiora reddam. |

They

are quite a lot of people indeed that devoted themselves with great

care in this search, among whom emerges your immortal Harvey*, whose

perfect observations are still so full of teachings for everyone to

confute above all my labours as being useless. Since nevertheless, as

he himself affirms, "the first sketches of nature are for the

greater part hidden as in a deep night, and with their thinness they

elude the acuteness of the intelligence no less than of the eyes",

and since the so polymorphous strength of nature, almost with

uncertain timeliness, now accelerates and now delays the appearing of

the fetus, therefore very learned Colleagues you will grant me to

communicate you some rough rudiments of observations inferred from the

analysis of brooded eggs, descriptions that I am proposing to repeat

rather often, so that, if you will find them consistent with nature

and your renowned minds, I can again confirm them during the coming

years, to amplify them by using similar finds and to increase them

with new data as far as it is possible to hope from my littleness. |

|

Inter

partes, quibus Ovum integratur, Cicatricula[3],

seu circularis macula, primum locum obtinet; in huius enim gratiam

reliqua comproducta videntur. Huius igitur mirabilis structura

indaganda sese offert, cuius praecipuas mutationes, et phaenomena

brevibus indicabo. |

Among

the parts composing the egg, the first place is owed to the cicatricle,

or circular patch, since it seems that thanks to it all the other

things are produced. Therefore its marvellous structure, of which I

will shortly point out the principal changes and appearances, is

offering itself to investigation. |

|

Haec

itaque in foecundo Ovo

perpetuo observatur arcte Vitelli membranae adhaerens inter chalazas[4];

et albumine cooperitur: multiplicatisque vitellis (ut videre potui)

eadem Cicatricula multiplicatur, unde frequenter in unico ovo tres

deprehendi Cicatriculas. |

Then,

in the fertilized egg, this cicatricle is constantly observed, tightly

sticking to the membrane of the yolk, that is set among the chalazas

and is covered by the albumen. In case of several yolks (as I

succeeded in seeing) the cicatricle is manifold, that's why often I

observed three cicatricles in only one egg. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

1. Fig. 2. - In ovis pridie editis, et nondum

incubatis (ut elapso Augusti

mense, magno vigente calore, observabam) Cicatricula magnitudinem

habebat A, hic a me ruditer

delineatam, in cuius centro sacculus cinerei coloris[5],

interdum ovalis B, quandoque

alterius figurae deprehendebatur. Innatabat huiusmodi sacculus seu

folliculus[6]

in colliquamenti C liquore[7],

vitro fuso persimili, qui irregulari quasi fovea[8]

continebatur: Candidus enim solidae substantiae circulus D[9],

aggeris instar, idem colliquamentum ambiebat, cuius exterior portio

fuso et liquido alluebatur humore E.

Subsequebatur parum lata substantia F,

frequenter varie lancinata, et humore G

pariter mergebatur. Alii insuper ampliores circuli H, ab eadem solidiori excitati substantia circumducebantur,

interpositis liquoris alveolis I.

Exteriores praecipue circulos H,

non uno ritu efficit Natura; nec hi perpetuo continua protrahuntur

substantia. In sacculo postea, velut in amnio[10],

dum solis radiis illum objiciebam, inclusum foetum L[11]

animadvertebam, cujus caput[12]

cum appensae carinae[13]

staminibus patenter emergebat: Amnii etenim rara et diaphana

contextura frequenter translucebat, ita ut contentum appareret animal.

Saepius acus acie folliculum aperiebam, ut contentum animal in lucem

prodiret; incassum tamen: ita enim mucosa erant adeoque minima, ut

levi ictu singula lacerarentur. Quare pulli

stamina in ovo praexistere[14],

altioremque originem nacta esse fateri convenit, haud dispari ritu, ac

in Plantarum ovis. |

In

eggs laid the previous day and not yet brooded

(as I was observing in the last month of August, when it was hot) the

cicatricle had the size A (fig. 1) here by me roughly drawn, at whose

centre was perceived a little sack, ash in colour, sometimes oval B

(fig. 2) and which sometimes had a different appearance. Such saccule

or follicle, floated in the liquid of colliquation C, very similar to

molten glass contained in a kind of irregular pit: in fact a candid

circle of solid substance D, as if being a bank, surrounded the

aforesaid colliquation, and its external part was wetted by the liquid

E melted and thawed.

Immediately after, the substance F was coming, not very wide, often

variously indented, and that likewise was soaked in the liquid G.

Furthermore other more wide circles H, derived from the same more

solid substance, were arranged around, with the interposition of

rivulets I of liquid. The nature doesn't make in the same way the

circles H, above all the more external ones, neither they are always

extending with continuous substance. After, while I was exposing it to

the rays of the sun, I perceived the fetus L held in the little sack

as being an amnion, and its head clearly emerged together with the

sketches of the hooked carina. In fact the loose and diaphanous weave

of the amnion often allowed the light to pass, so that the animal,

contained in it, was visible. I rather often was opening the follicle

with the point of a needle so that the animal contained in it came to

the light. Nevertheless uselessly: in fact the structures were so

sticky and so much little that all of them were tearing at the

slightest trauma. That's why it is worthwhile to admit that the

sketches of the chick are pre-existing in the egg and that they had a

more remote origin, not otherwise it is happening in the eggs of the

plants. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

3 - Placebat etiam subventanea ova[15]

lustrando cicatriculam intueri, quae ut plurimum minima erat; et licet

variam sortiretur circumscriptionem, et texturam, frequentius tamen

delineatam A prae se ferebat

effigiem. Non longe a centro globosum candidumque corpus, seu cinereum

B, quasi mola, locabatur;

quod laceratum nullum peculiare exhibebat corpus a se diversum.

Appendices reticulares C

habebat, quarum spatia diversas referebant figuras, non raro ovales,

diaphanoque replebantur colliquamento; denique tota haec moles, Iridis

instar, plurimis circumdabatur circulis. |

Observing

the windy eggs it seemed me correct

to examine also the cicatricle, that for the more was very small; and

even if having variable contours and structure, nevertheless rather

often was showing the appearance reproduced in A (fig. 3). Not far

from the centre a globular and snow-white formation B, or else ash in

colour, was found, almost similar to a vesicle; after being lacerated,

it didn't show some particular structure different from its one. It

had adnexa C arranged as a net whose spaces had a variable appearance,

not rarely oval, and they were full of a diaphanous fluid liquid;

finally this whole mass was surrounded by a lot of concentric circles

as the rainbow. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

4. - In incubatis autem

Gallinae ovis sub Indica vel nostrate gallina, summo vigente aestu,

tales attingebam mutationes: et primo immediate [3]

post sex incubatus

horas, Cicatricula huius erat magnitudinis A;

in cuius centro aderat Amnion, scilicet B,

candido solidoque circumvallatum aggere C,

quod colliquamenti liquore fusco replebatur. In

medio, pulli carina D una

cum capite innatabat. Huius inferior portio frequenter disrupto

folliculo E[16] contegebatur. Amplus

subsequebatur circulus F, fasciae instar ambiens, qui tandem umbilicalibus pervadebatur

vasis. Non ubique solidum corpus erat, sed sensim irruente ab

exterioribus rivulis colliquamento solvebatur, collis instar, qui

erumpentibus interluitur et mergitur fontibus. Hoc solidiori circulo

subcandido, parumque lato G ambiebatur, qui rivulis et ipse

intercipiebatur. Interdum alii subsequebantur circuli qui incubationis

progressu frangebantur, vel tandem obliterabantur. |

In

eggs of hen brooded by a turkey hen or by a home hen

at the height of summer - 1671 - I observed the following

changes, and first of all, immediately after

6 hours of incubation, its cicatricle

was large as A (fig. 4). At its centre was present the amnion, or B,

surrounded by a snow-white and solid vallum C, full of a dark liquid

of colliquation. In the centre the carina D of the chick fluctuated

together with the head. Its inferior part was often covered by the

lacerated follicle E. The wide circle F was following, enveloping as a

band, that finally was pervaded by the umbilical vessels. It was not a

solid structure in every point, but was gradually melted by a

penetrating colliquation coming from external rivulets, as a hill

irrigated and submerged by sources gushing with violence. This

structure was surrounded by a more solid circle G, whitish and not

very wide, it too interrupted by rivulets. Sometimes other circles

were following each other, interrupted by the progress of incubation,

or were finally deleted. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

5. - Post horas duodecim incubatus, exaratae partes distinctius patebant in

adaucta cicatricula, magnitudinis A,

quae sursum emergens fere horizontalis erat. Disrupto itaque folliculo

B[17],

foetus C erumpebat insigni capite, et duplici vertebrarum ordine[18],

carinae inchoamenta excitante: Hujusmodi namque candidi orbiculares

sacculi, seu vesiculae, invicem contiguae, deorsum excurrebant,

spinalisque medullae[19]

stamina stipabant; et cerebri[20]

pariter primordia subobscure emergebant. Candidus de more circulus D,

Amnion efformaturus, in exteriori colliquamento E

innatabat. Pars F[21],

quae tandem colliquatur, et umbilicalibus vasculis substernitur,

amplior reddita ex subiecto vitello subluteum referebat colorem, et in

ichorem[22]

fusa ab adveniente colliquamento, quasi rivulis, interrumpebatur: In

his tamen motum aliquem non videbam. Candidus circulus G,

omnia de more continens, subsequebatur. Non semel ulteriorem videbam

latam veluti fasciam H, in

qua reticularem plexum I, spadicei

coloris[23],

deprehendebam, vasorum implicationem aemulantem, cuius spatia

exterioris ambitus arctiora erant et sensim obliterabantur, interiora

autem laxiora. An vero huiusmodi sint Umbilicalia

vasa, quae iam in colliquamenti materia latentia, progressu

temporis aeruginoso ichore, et tandem rubescente sanguine turgeant; an

sinus et alveoli ex fermentato colliquamento viam sibi faciente;

determinare non audeo, cum ex humoris diaphaneitate, et sinuum

angustia, localis motus

imperceptibilis existat. |

After

12 hours of incubation, the described

parts were more distinctly visible in the increased cicatricle, whose

size was corresponding to A (fig. 5), and sticking out upward it was

almost horizontal. Therefore, after having opened the follicle B, the

fetus C emerged from it, endowed with a big head and two rows of

vertebrae forming the sketches of the carina. In reality such white

and round pouches or vesicles, neighbouring each other, stretched

downward and surrounded the sketches of the spinal marrow; and also

the sketches of the brain were emerging in a no very evident way. The

circle D, snow-white as usual, destined to form the amnion, floated in

the more external colliquation E. The part F, that at the end is

liquefying and placing itself under the small umbilical vessels, after

becaming greater, was taking a yellowish colour from the underlying

yolk, and melted into ichor - into liquid - was interrupted as by

rivulets by the tributary colliquation: nevertheless in them I didn't

see any movement. The candid circle G was following, that as usual

enclosed every thing. More

than once I

observed a following formation H ample as a band, in which I perceived

the reticular plexus I of colour of the date - dark red - similar to

an interlacement of vessels, whose spaces in the external area were

more narrow and gradually disappeared, while those more internal were

wider. But I don't dare to establish if these formations are umbilical

vessels which, already latent in the material of colliquation, with

the passing of time are swollen of rust coloured liquid and then of

red blood, or if they are sinuses and rivulets coming from the

fermented colliquation making its way. I don't dare to establish these

hypotheses since, on the basis of the transparency of the humour and

the narrowness of the sinuses, doesn't exist any perceivable local

movement. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

6. - Parum absimilis structura

in incubata cicatricula per horas decem

et octo, ovi apicem horizontaliter tenente, emergebat: Namque

pullus A amplo capite, et

oblonga spina, quae disrupto folliculo B

obtegebatur, in adaucto colliquamento de more mergebatur, superstite

adhuc circulo C. Ambiens

pariter substantia D,

colliquamenti rivulis E,

versus Amnion irruentibus[24],

irrigabatur; nondum tamen sanguinea vasa prodibant, Occurrebat amplior

circulus F, rivulo

interposito G, cuius

continuitas in aliquibus tolli coeperat, et quandoque plures ulterius

circuli addebantur. |

In

the cicatricle incubated for 18 hours,

occupying horizontally the higher part of the egg, a little dissimilar

structure was evident. In fact the chick A (fig. 6) with a big head

and a lengthened spinal column, covered by the lacerated follicle B,

was immersed as usual in the increased colliquation, still persisting

the circle C. Item the substance D placed around was irrigated by

rivulets E of colliquation throwing themselves toward the amnion;

however blood vessels had not yet appeared. A wider circle F was

present, with the interposition of the rivulet G, whose continuity in

some eggs had started to stop, and sometimes many further circles were

adding. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

7. - Post diem integrum horarum

24, saepe cicatriculam in summo emergentem, latioremque redditam,

qualem hic delineavi, videbam. Pullus enim A

cum capitis et spinae candido inchoamento, versus inferiora recurvo,

in colliquamento B

sub-oscuro innatabat, et lateri interdum [4]

sinistro folliculi, vel

circuli fragmento G haerebat;

ambiens vero substantia D,

rivulis excavata, extendebatur, et exterior circulus E,

liquore circumdatus, cicatriculae compagem claudebat, ita tamen, ut

derivato ab alveolis exterioribus F

colliquamento versus D

pateret aditus. |

After

a whole day of 24 hours I often saw

that the cicatricle was sticking out at the summit and had become

wider, as I have drawn it here (fig. 7). In fact the chick A, with the

snow-white sketch of head and column bent downward, was floating in

the colliquation B a little bit dark, and sometimes it clung to the

left side of the follicle or of the circle with the portion G; then

the surrounding substance D was extending, dug by rivulets, and the

most external circle E, surrounded by liquid, was closing the

structure of the cicatricle, however in such a way that to the

colliquation F, derived from the external rivulets, a free access

toward D was guaranteed. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

8. - In Vegetiori ovo interdum

singula evidentiora occurrebant; pullus enim in colliquamento A residens oblongiori pollebat carina, eaque recta, quae multis

vertebrarum globosis inchoamentis B[25],

hinc inde a spina locatis, compaginabatur. Alae C[26]

crucis in modum pariter erumpebant, et reliquum capitis, colli, et

thoracis, crassius redditum elongabatur. Tres ampliores vesiculae D, cum producta spinali medulla E[27], usque ad extremum carinae emergebant, et binae pariter orbiculares

globuli F, hinc inde in

capite reponebantur, forte oculorum inchoamenta. Circulus G, olim

colliquamentum ambiens, superiori foetus parti substernebatur.

Umbilicalium vasorum H

surculi primo prodibant, qui contorti e varicosi in colliquamento

mergebantur, nec ipsorum continuata productio adhuc patebat, unde

variae obiiciebantur species; contentus vero humor, interdum

subvitellinus, quandoque rubiginosus erat; huius motum nequaquam

deprehendere valebam. Cordis

motum licet visus fuerim attigisse, non tamen certo affirmare

audebam. |

In

a more vigorous egg sometimes the details were appearing more evident.

In fact the chick located in the colliquation A (fig. 8) was endowed

with a longer and straight carina, which was composed of numerous

spherical sketches B of vertebrae arranged at both sides of the column.

Also the crosswise arranged wings C were sprouting, and the remaining

parts of head, neck and thorax had become thicker and longer. Three

rather great vesicles D, together with the spinal marrow E in

continuity with them, were emerging until the extremity of the carina,

and likewise at each side of the head two spherical globules F were

located, perhaps the sketches of the eyes. The circle G, before

surrounding the colliquation, was below the superior part of the fetus.

For the first time the small branches of the umbilical vessels H

appeared, that, twisted and dilated, were plunged in the colliquation,

but an uninterrupted extension of them was not yet evident, hence

different appearances were noticed. The liquid they contained

sometimes had a colour similar to yolk, other times it had a rust

colour. I was not able at all to catch a movement of it. Although it

seemed me to have noticed a movement of the heart, nevertheless I

didn't dare to affirm it with certainty. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

9. - Absumptis triginta horis, cicatricula taliter configurabatur: In adaucto

amnio A, iacebat pullus B,

in quo novae nondum emerserant partes, praeter capitis appendices, in

aliquibus parum elongatas. Circa amnion perpetuo varicosa umbilicalia

vasa C observabantur, quae

in exteriori limbo D[28]

ampliora, et magis continua, coloris aeruginosi, extendebantur; versus

interiora tamen obscurabatur ipsorum progressus turgente colliquamento:

unde tunc temporis eatenus haec in oculos incurrere dubitabam,

quatenus conglobata reddebantur. Ambientes circuli E,

fusique humoris rivuli F, multiplicabantur,

qui recollectum umbilicalibus, et amnio subministrabant: Non tamen

haec alveolorum ad amussim species obiiciebatur, sed varia quandoque a

Natura promebatur. |

When

30 hours passed, the cicatricle was

shaped as follows. In the amnion A (fig. 9), that had grown, the chick

B was laying, in which new parts not yet sprouted, except the cephalic

appendixes, a little lengthen in some chicks. Around the amnion

umbilical dilated vessels C were always observed, that in the more

external edge D were greater and more continuous, of rust colour.

Nevertheless toward the inner parts their progress was hidden by the

swollen colliquation: therefore then I doubted that such vessels were

visible until they were conglobated. The concentric circles E and the

rivulets F of melted liquid were increasing in number, which supplied

the collected matter to umbilical vessels and amnion. However this

appearance of the canaliculi didn't appear exactly, but sometimes was

shown different by nature. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

10. - Elapso die cum dimidio, parum absimilis occurrebat configuratio. Caput A

solitis vesiculis turgidum, cum alarum inchoamentis B,

et spinali medulla C,

patebat; extremitas carinae D

curvabatur; Umbilicalium vasorum exterior limbus E,

quasi continuato vasculo, adhuc subruginosum continente humorem,

terminabatur, et continuati surculi F,

reticulariter impliciti, versus interiora erant producti. |

When

one day and a half passed, the

appearance was not very dissimilar. The head A (fig. 10) was evident,

swollen by the usual vesicles together with the sketches B of the

wings and spinal marrow C; the extremity of the carina D was bent; the

most external edge E of umbilical vessels was delimited by a small

almost continuous vascular structure still containing an almost rust

coloured liquid, and the little branches F, continuous in structure

and netlike interwoven, were going toward the inner structures. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

11. - Evidentius patuere singula post incubatum horarum triginta octo. Auctior pullus insigni capite A pollebat, in quo tres vesiculae[29]

situabantur, quarum amplior figuram B

prae se ferebat; circum tamen obducebantur involucra C, totum spinae tractum ambientia, quam vertebrarum rotundi

sacculi D de more

componebant. Supra Alarum

exortum, Cordis E structura

primo patebat; quam antea interdum, dubie tamen, mihi detexisse visus

fueram: Vivente enim animali pulsus observabatur; quo cessante fusca

tandem quasi linea designabatur. In colliquamento F

fragmenta circuli G adhuc

supererant. Umbilicalia vasa H

conspicuis surculis varicosis et reticulariter [5]

unitis circum abstabant,

nec adhuc ipsorum productio usque ad Cor emergebat; supernatante enim

colliquamento vel crassiori albumine obscurabantur: Ichor pariter

circum-affundebatur cum innatantibus circulorum solidis fragmentis. |

Each

structure became more evident after an incubation of 38 hours.

The chick, of higher dimensions, was endowed with a big head A

(fig.11) in which three vesicles were located, the greater one showing

the appearance B; nevertheless the wraps C were stretched all around,

surrounding the whole section of the column, composed as usual by the

round vertebral pouches D. Above the origin of the wings appeared for

the first time the structure of the heart E, which sometimes

previously seemed me to identify, even if with some doubts. In fact in

the still alive animal a pulsation was visible, but at its stop a dark

line so to say was drawing. In the colliquation F fragments of the

circle G were still present. The umbilical vessels H were arranged

around with large dilated branches and joined to make a net, but their

lengthening until the heart was not yet noticed; in fact they were

hidden by the above colliquation or denser albumen. Likewise liquid

containing solid floating fragments of circles was spreading all

around. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

12. - Quadraginta elapsis

oris, pullus in colliquamento A degens

pulchrum exhibebat spectaculum; nam crassefacta carina, Caput B curvabatur; Cerebri vesiculae C non ita patentes erant; oculorum D inchoamenta emergebant; Cor E

pulsabat recepto a venis humore, rubiginosi et interdum

xerampelini[30]

coloris: Exterior namque umbilicalium limbus venoso quasi circulo

crassiori F circumducebatur,

qui finibus praecipue G[31]

in cor hiabat: Talis autem ex contento sanguine via, et continentium

structura indicabatur, qualem hic delineatam intuemini. |

When

40 hours passed, the chick, laying in

the colliquation A (fig. 12), was showing a beautiful appearance. In

fact, the carina being increased, the head B was bent; the cerebral

vesicles C were not so apparent; the ocular sketches D were sticking

out; the heart E pulsated, having received from the veins some liquid

rust coloured and sometimes of the colour of a drying leaf of vine: in

fact the external band of the umbilical vessels was surrounded by a

kind of thicker venous circle F, that opened in the heart mainly with

the terminations G. Really such a way, due to the contained blood and

to the appearance of the structures containing it, was put in evidence

as you can see it drawn here. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

13. - Primo itaque motus

Constrictionis ex appulso humore per

venas A[32]

observabatur

evidenter in auriculam B[33];

a qua expressus succus propellebatur per C[34]

in amplum ventriculum dextrum D[35],

qui constrictione media in continuatam appendicem E[36]

protrudebatur, a qua in arteriam Aortam F

patebat aditus; haec autem sursum in caput insignes emittebat ramos[37],

et deorsum in truncum G[38]

se elongabat, qui divisus usque ad extremum carinae producebatur; Fig.

12. -versus tamen mediam regionem umbilicales ramos H[39]

promebat, qui germinatis surculis I

in peripheria absumebantur, excitato reticulari plexu, quem in

relinquorum vasorum sanguineorum extremitate perpetuo miramur.

Consimilis etiam implicatio observabatur circa venosum vas F[40];

quin adhuc vereor, ne sit latum vas, an vero conglomeratus reticularis

plexus venosus, cum frequenter huius vestigia deprehenderim. Pulsantes

itaque successive hasce vesiculas[41]

Verum Cor esse censeo, circa

quas (ut non semel suboscure videbam) musculosae carneae portiones

circumducebantur, nondum opacitatem aut rubedinem sortitae. Quare

motum illum, qui in micante gutta, seu saliente puncto, alias observatus est, nequaquam palpitationem

inclusi sanguinis[42]

esse reor, sed veri cordis motum, pulsum scilicet constrictionis

et dilatationis, qui successive peragitur in debitis ventriculis,

solo loco disparatis, qui tandem uniti, inducta carne, consuetam

adulti cordis excitant fabricam. |

Therefore

it was first of all observed in a well visible way the movement of the

systole thanks to the liquid pushed through the veins A (fig. 13) in

the auricle B, and the liquid it squeezed was pushed through C in the

wide right ventricle D which, after having halved itself, debouched

into the adjacent appendix E, from which the access to the aorta

artery F was opening. Then this was sending forth some big branches in

cranial direction and was lengthening downward in the trunk G that,

after having divided, pushed until the extremity of the carina.

However approximately in the central area it was sending forth the

umbilical branches H (fig. 12), which, after gave origin to the little

branches I, were dispersing in the periphery after having formed a

reticular plexus, as we regularly observe at the extremity of the

other blood vessels. Analogous interweaving was also observed around

the venous vessel F; so that I still fear that it is not a big vessel,

but a venous reticular curled up plexus, since often I observed its

traces. Therefore I believe that these vesicles, subsequently

pulsating, are the true heart, and around them (as many times I saw

not very distinctly) were placed portions of muscular flesh that had

not yet acquired redness and opacity. Then I think that that movement

observed other times in the vibrating drop, or hopping point, is not

at all the palpitation of the contained blood, but the movement of the

true heart, that is, a tightening and dilating pulsation - systole and

diastole - and that it is fulfilled in succession in the ventricles to

this destined, distinguished only by their position, which finally

join up and become covered with flesh, and assume the usual structure

of the adult heart. |

|

Difficillimum

quidem est sensu ipso confirmare, An Sanguis prior sit exarato Corde?

Licet enim frequentissime fuscus et rubiginosus humor in exterioribus

umbilicalium vasorum finibus appareat nondum videnter emergente Corde;

et speciosum videri possit, Cor fieri excurvato et expanso vase, cui

carneae portiones, veluti manus, exterius aptentur; quoniam tamen tunc

temporis ita mucosa, candida, et lucida sunt omnia, ut sensus

quocunque instrumento munitus nequeat distinctam partium compagem

attingere, et, sicut in Insectis videre est, ultimi senii partes in

primordiis rudimenta habere, ita de Corde adhuc mihi dubitandum

superest: Hoc autem certo sensui patet, Sanguinem seu sanguineam

materiam a primordiis non omnia illa habere, quae in ipso ex post

deprehenduntur. Primo namque colliquamenti species, a rivulis versus

foetum deducti, in vasis patet; mox vi fermentationis sub-vitellinus

et rubiginosus emergit humor, [6]

qui tandem rubicundus evadit; sub postremis hisce naturis, cordis

ministerio in gyrum pellitur. Quare vereri possumus, quod, sicuti in

Sanguinea materia successivae mutationes, inducto colore,

manifestantur; ita pariter cordis structura solo motu evidenter pateat,

et quod quiescens adhuc praeexistat, licet iners, nondum scilicet

firmatis carneis fibris. Hoc vero certum videtur, Ichorem, seu

exaratam materiam, quae postremo rubicunda efficitur, Cordis motum

antecedere; Cor vero suo etiam motu Sanguinis rubificationem. |

Really

it is very difficult to confirm, just basing themselves on the visual

experience, if the blood is pre-existing to the heart we described. In

fact, although very often a dark and rust in colour liquid appears in

the outer extremities of the umbilical vessels when the heart is not

still clearly visible, and although it could seem beautiful that the

heart derives from a bent and expanded vessel, externally to which

pieces of flesh are arranging themselves as being hands; since

nevertheless in such moment everything is so mucous, snow-white and

bright that the eye provided of whatever tool would not be able to

distinctly detect the structure of the parts, and that, as it can be

seen in insects, the parts of the farthest old age have the sketches

in the initial structures; then I am still doubtful about the heart.

In fact to the sight it is certainly clear what follows, that the

blood or haematic material doesn't possess since the beginning all

those things subsequently observed in it. In fact at first in the

vessels something is evident seeming a colliquation, transported by

the rivulets toward the fetus; soon after through the action of the

fermentation a yellowish and rust coloured liquid is highlighting,

finally becoming red, and under this final appearance is pushed around

by cardiac activity. Which is why we can suspect that, as in the

haematic material some following changes are showing themselves

through the assumed colour, so likewise the structure of the heart is

showing itself in a clear way by only the movement, and that it is

pre-existing still quiescent, although inactive, since the fleshy

fibres didn't yet grow stronger. It seems certain what follows, that

the liquid, that is, the described material finally becoming red,

precedes the movement of the heart, as well as that the heart starts

to pulsate before the blood becomes red. |

|

An

autem Ichor primo emergens sit simplex colliquamentum, an vitalis

liquor, an sanguis inchoatus, cum sensuum ministerio determinari

nequeat, vestris mentibus diiudicandum relinquo; illud unum innuens,

ante Ichoris collectionem, eiusdem motum, et in sanguinis naturam

conversionem, Carinam, cum capitis, cerebri, spinalis medullae, et

alarum[43]

inchoamentis, evidenter patere; et sicut in Plantarum Ovis primo

colligitur colliquamentum, ex quo ab initio Plantae carina sive

truncus cum foliis excitatur; quae singula diversis Vasis, succisque

fermentativis concretis compaginantur: ita in Animalium primaeva et

simultanea productione dubitare fas est; cum suspicari possumus, in

Ovo subesse pullum, cum partium fere omnium conterminis sacculis

innatantem in colliquamento, huiusque naturam nutritivis et

fermentativis succis commixtis integrari, ex quorum suscitata mutua

actione sanguis successive progignitur, partesque olim delineatae

erumpunt, et turgent. Sed tam involuta et latentia sunt haec Naturae

opificia, ut licet sensuum ministerio inquirantur, quoniam tamen circa

minima versantur, facile (me saltem) decipere possint; ideo irritum

prorsus censeo meis coniecturis ea prosequi. Quare redeo ad indagandas

successivas pulli manifestationes. |

But,

being impossible to establish by the employment of the senses if the

liquid at first appearing is a simple colliquation, or a vital liquid,

or a sketch of blood, I leave it to be judged by your minds. I confine

myself to mention that the carina, together with the sketches of head,

brain, spinal marrow and wings, shows itself in evident way before the

liquid gathers, starts to move and turns into blood. And as in the

eggs of the plants at first the colliquation is gathering, from which

since the beginning the carina of the plant originates, that is, the

trunk, together with the leaves, and each structure is composed of

different vessels and thick fermentative juices, it is permissible to

doubt that so happens in the juvenile and simultaneous formation of

the animals, since we can suspect that in the egg the chick hides

itself, floating in the colliquation, with the contiguous pouches of

almost all the parts, and that its nature is renewed by the mixture of

nourishing and fermented juices, thanks to whose mutual stimulation

the blood is subsequently begot, and the parts, for a long time

delineated, erupt and increase. But these laboratories of nature are

so dark and hidden that, as far as they are investigated by using the

senses, being that nevertheless they concern very small things, they

could easily deceive (me at least). Therefore I think undoubtedly

useless to expound them by using my conjectures. Which is why I go

back to the following manifestations of the chick that have to be

investigated. |

|

Non

in singulis incubatis quacunque tempestate ovis, Cor et appensa

Umbilicalia vasa tam cito manifestabantur: Frequenter enim elapso

altero die emergere solebant; autumno praecipue, et vere, ut saepius

mihi accidebat. Inter observandum, in obscuro etiam conclavi, nunquam

micantem in Corde lucem, etiam

minimam[44],

attingere potui. |

The

heart, and the umbilical vessels suspended from it, didn't show

themselves as much soon in each egg incubated in whichever season: in

fact often they were accustomed to appear when the second day was

passed, especially in autumn and in spring, as rather often it

happened me to observe. Also during the observations in a darkroom,

never I succeeded to see in the heart the slightest sparkling light. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

14. - Binis

superatis diebus,

utplurimum consimilis occurrebat species, qualem delineare mea

manu tentavi; prout nudis etiam oculis obiicitur. Colliquamenti

sacculus, seu amnion A,

copioso fuscoque refertus ichore, Pullum continebat, cuius vesiculae

recurvum caput integrabant; vertebrarum sacculi per longum producti

adhuc patebant; cor B extra

thoracem pendulum, triplici, hocque successivo, pulsu movebatur. Nam

receptus humor, quandoque adhuc rubiginosus, a vena per auriculam in

cordis ventriculos, ab his in arterias, et postremo in umbilicalia

vasa C demandabatur. Saepe

servabam pullum, et exsiccato subiecto vitello, Cor per diem pulsum

non intermittebat. Umbilicalium vasorum limbus D, lato quasi vase terminabatur, cuius quidem crassitiem ex

implicatione reticulari venarum et arteriarum excitari censeo; quod

tamen ulteriori eget inquisitione: Exonerabantur autem venae mediis

extremis finibus E in

auriculam cordis. |

When

2 days passed, mostly was occurring

an appearance similar to that I tried to draw with my hand, so as it

is occurring also to naked eyes. The pouch of the colliquation, that

is the amnion A (fig. 14), full of abundant and dark liquid, contained

the chick, whose vesicles were leaning against the bent head; the

pouches of the vertebrae were also visible, longitudinally placed; the

heart B, hanging outside the thorax, was moving by triplex and

following pulsation. In fact the liquid received from the vein,

sometimes still rust coloured, was sent through the auricle in the

ventricles of the heart and from these in the arteries, and finally in

the umbilical vessels C. Often I conserved the chick and, after the

underlying yolk dried, the heart didn't stop pulsating for one whole

day. The band D of the umbilical vessels was ending as in a wide

vessel whose size in my opinion is provoked by the reticular weaving

of veins and arteries. Nevertheless this needs a further investigation.

Besides the veins were discharging, through the central and terminal

extremities E, in the auricle of the heart. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

15. - Valde solicitus eram

circa primaevam Cordis

apparentem formam, et, quam attingere potui a contento sanguine

delineatam, hic habebitis. [7] Ex quibus patet, sanguinem perpetuo a venis A, a limbo deductis, deferri in auriculam B, a qua, brevi interdum intermedio canali, in dextrum cordis

ventriculum C exprimitur, et

inde in sinistrum D, et

tandem in arterias E, a

quibus in caput F, et

umbilicalia vasa G. |

I

was very attentive about the appearance of the primordial shape of the

heart and you will find it here as I have been able to observe it

outlined by the contained blood. From these images it is evident that

always the blood from the veins A (fig. 15), coming from the band,

passes in the auricle B, from which, through a sometimes brief

intermediary channel, is pushed in the right ventricle C of the heart,

and from here in the left D, and finally in the arteries E, and from

them in the head F and in the umbilical vessels G. |

|

Circa

exaratos Sanguinis ductus fibrosa diaphanaque musculosae carnis portio

extendebatur, ut subobscure videbam; cuius necessitatem pulsus arguit.

Non semel sanguineos ramos A

a cordis auricula et dextro ventriculo elongatos licet deprehenderim;

adhuc tamen haereo, cum mihi ambigendum occurrerit, productiones esse

subiectorum Umbilicalium vasorum[45]. |

Around

the described blood's ducts a fibrous and diaphanous portion of

muscular flesh was stretching, as I was able to observe in a rather

uncertain way, and the pulsation shows the necessity of it. Even if I

have observed not only once that the blood branches A are departing

from the auricle of the heart and from the right ventricle,

nevertheless I am still doubtful, being happened me a reason for

doubting, if they are ramifications of the underlying umbilical

vessels. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

16. - Post binos

dies, horasque quatuordecim, pullus pariter auctior redditus,

in colliquamento A, curvo capite, pronus iacebat; cerebri vesiculae B,

sanguineis vasis irrigatae, cum oculorum inchoamentis C;

spinalis item medulla per longum exporrecta, vertebris D contenta, observabantur: Externum corporis habitum colliquamenti

E portio, crassior et

obscurior reddita, veluti involucrum[46],

ambiebat: a corde emanabant sanguinea vasa, quae producta versus

medium abdominis, umbilicales arterias F,

et venas G etiam, promebant: Patebant autem venae G, una cum arteriis excurrentes, ex inverso sanguinis motu, et

eandem fere magnitudinem cum arteriis acquisiverant. Extremus

Umbilicalium vasorum limbus H

sanguineis vasculis excitabatur crassefactis, vel saltem reticulariter

implicitis. Placebat, repetitis observationibus, Cordis motum et

figuram rimari, quae talis apparebat; Sanguis partim ab extremo limbo H, et a vena ascendente et descendente I, in auriculam K

eructabatur; haec postea pulsu edito ipsum propellebat in cordis

ventriculum L, qui

constrictione media pallidus efficiebatur, et in proximum ventriculum M,

et tandem in aortam protrudebat, a qua capiti, corporis habitui, et

umbilico communicabatur. |

After

2 days and 14 hours the chick had

become meanwhile greater and was laying prone, with the bent head, in

the colliquation A (fig. 16). The brain vesicles B were visible,

bedewed by blood vessels, together with the ocular sketches C, as well

as the spinal marrow longitudinally arranged and held by the vertebrae

D. The portion of the colliquation E, made denser and darker, was

surrounding, as if being a wrap, the outer part of the body. From the

heart some blood vessels were departing that, going toward the middle

part of the abdomen, sent forth the umbilical arteries F, and also the

veins G. Really the veins G, flowing together with the arteries, were

clearly recognizable from the inverse movement of the blood, and had

acquired almost the same size of the arteries. The most outer band H

of the umbilical vessels was composed of thickened little blood

vessels, or at least woven as a net. I thought advisable to examine,

with repeated observations, the movement and the shape of the heart

appearing as follows: the blood, coming partly from the most external

band H and from the ascending and descending vein I, flowed in the

auricle K; then this, resorting to a pulsation, pushed it in the

ventricle L of the heart, that at half contraction became pale, and

pushed it in the near ventricle M and finally in the aorta, from which

was sent to head, to bodily structure and to navel. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

17. - Transacto triduo, curvo et prono corpore cubantem reperiebam pullum; in

cuius capite A, ultra binos

oculos B, quinque vesiculae C,

humore turgidae, quibus coagmentatur cerebrum: Crurum quoque D

et alarum E inchoamenta

patebant. Vesicularum, cerebrum integrantium, situs et forma talis

erat: In capitis vertice amplior locabatur vesicula[47],

vasculis irrigata, hemisphaerae instar; haec subsequentibus diebus in

binas dividebatur quasi vesiculas[48]:

Unde adhuc haereo, an a principio una an gemina sint vesiculae. In

occipite triangularis quasi vesicula G[49]

addebatur;

sincipitis[50]

vero profundam partem tenebat ovalis vesicula H[51],

cui proxime

locabantur binae vesiculae I[52].

Corporis habitum inducta

caro contegebat, ita ut sanguinis via non ita facile in oculos

incurreret. Oculi B eminebant, et ipsorum pupilla nigra, circularique zona in ima

parte discontinuata[53]

excitabatur; centrum vero crystallinus vitreo contentus tenebat. Prope

eruptionem umbilicalium vesicula K

extra pendebat, sanguineis vasculis irrigata, quem carnosum

ventriculum[54]

censeo. Cordis compages talis erat, qualem hic exhibebo: Naturae enim

mysterium, quod superius innuebam, hac die evidenter patebat; Auricula

namque L sanguinem [8]

a venis M

recipiens, quasi gemino pulsabat motu, veluti binis distincta

ventriculis, et ita in cor sanguis quadam propellebatur via, quae

ulteriori eget indagine. Dexter cordis ventriculus N,

a primordiis notus, de more pulsabat, sinister vero et ipse distincto

motu agitabatur, et latior indies reddebatur, donec consocio unitus

ventriculo pro sinistro manifestaretur; quod subsequentium dierum

inspectionibus magis patebat. |

When

3 days passed, I found the chick

laying with a prone and bent body, and on its head A (fig. 17),

besides the two eyes B, I found 5 vesicles C turgid of liquid, and of

them the brain is made up. Also the sketches of legs D and wings E

were evident. The arrangement and the shape of the vesicles composing

the brain was the following: at the top of the head the greatest

vesicle - F - was located, bedewed by little hemispheric vessels, and

in the following days it was subdividing as in two vesicles; which is

why I am still in doubt if initially the vesicles are only one or two.

In the occipital place an almost triangular vesicle G was added and an

oval vesicle H occupied the deep part of the sinciput, and near H were

situated the two vesicles I. The superimposed flesh was covering the

body surface, so that the way of the blood didn't easily penetrate in

the eyes. The eyes B were bulging, and their pupil lifted in a black

and circular band, interrupted in the inferior part; the crystalline

contained in the vitreous

body occupied the centre. Near the point of coming out of the

umbilical vessels a vesicle K was hanging outside, bedewed by small

blood vessels, I think it to be the muscular stomach. The structure of

the heart was as here I will show: in fact in this day it was clearly

evident the mystery of nature to which I was previously pointing. In

fact the auricle L, receiving blood from the veins M, pulsated almost

with a double movement, as if it was divided in two cavities, and so

the blood was pushed in the heart through a way needing a further

investigation. The right ventricle N of the heart, known since the

beginning, pulsated as usual, while also the left one got excited with

a separate movement and was becoming larger day by day, until, joined

with the other ventricle, it appeared as being the left one; this was

more evident in the observations of the following days. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

18. - Quarta elapsa die manifestior evaserat pullus. Perampli cerebri quinque

vesiculae A adhuc patentes,

magis ad invicem approximabantur, et laceratae ichorem etiam reddebant;

oculi B magis tumidi

expositam servabant figuram; alae D,

et crura E magis elongata,

solidiora reddebantur. Extremitas pariter carinae F

uropygium constitura recurva prominebat; totum corpus adaucta

mucosa carne tegebatur, et vasorum irrigabatur propaginibus; Interior

cavae et aortae progressus condebatur, et funiculus umbilicalium

vasorum G ab abdomine

erumpebat sanguis per arterias propulsus rubicundo saturatoque

inficiebatur colore; qui vero per venas regrediebatur, subluteus erat.

Interius Ichoris[55]

inchoamentum, et candida intestina cum carnoso praecipue ventriculo,

mucosa tamen, manifestabantur. In aliquibus extra thoracem Cor H pendulum situabatur, cuius auriculae I, eidem magis approximatae, sanguinem a venis K

recipiebant, et cordis ventriculis subministrabant: dexter etenim

ventriculus L consuetam sortitus figuram, sinistro M nectebatur, qui latior redditus, retracto aortae principio N,

sensim debitam induebat formam: In aliis vegetioribus ovis, clausa

levi tunica thoracis cavitate, cor intus celabatur, et sinister

ventriculus deorsum pendulus consocio incumbebat ventriculo. |

When

the 4th day passed, the chick was

more evident. The five vesicles A (fig. 18), even more evident, of the

very big brain, were more approaching each other and, when lacerated,

they also sent forth a serosity. The eyes B, more swollen, were

keeping the described appearance. The wings D and the legs E, longer,

were becoming stronger. Item the bent extremity of the carina F was

sticking out, that would have formed the

uropygial gland*. The whole body was covered by mucous

increased flesh and was bedewed by offshoots of the vessels. The inner

way of vena cava and aorta was hidden, and the funicle G of umbilical

vessels was emerging from the abdomen, and the blood pushed through

the arteries was becoming tinged with a red saturated colour, while

that getting back through the veins was yellowish. The sketch of the

liquid - of the liver - and the very white bowels but mucous, above

all with the muscular stomach, were visible more inside. In some

embryos the heart H was pendulous outside the chest and its auricles

I, closer to it, received the blood from the veins K and sent it to

the ventricles of the heart. In fact the right ventricle L, endowed

with the usual appearance, was connecting to the left ventricle M,

which, being become greater, and the initial part of the aorta N

having shortened, was gradually assuming the proper shape. In other

more vigorous eggs, the thoracic cavity having closed through a thin

membrane, the heart was hiding itself inside and the left ventricle,

pendulous outside, was above the ventricle its companion. |

|

Post

quintam diem in incubato ovo

nil fere novi deprehendebatur praeter maiorem enarratorum

manifestationem. Vasorum umbilicalium extremus limbus, vitellum

ambiens, non excurrente trunco excitabatur, sed ipsorum extremi fines

lateraliter curvati et reticulariter inosculati extremum sortiebantur

terminum. Circa huiusmodi ramos, globuli seu placentulae, ex vitelli

substantia excitatae, hinc inde haerebant. In Vitelli semisphaera,

quae umbilicalibus vasis non tegitur, diversi alveoli, non dissimiles

a cicatricis rivulis, excitabantur. |

After

the 5th day almost nothing new was

observed in the incubated egg, except a greater evidence of the

described things. The most external band of the umbilical vessels

surrounding the yolk was not made by a continuous tract, but their

terminal segments, bent sideways and anastomosed as a net, were ending

at the extreme periphery. Around such branches were sticking at both

sides some globules or small bannocks derived from the substance of

the yolk. In the hemisphere of the yolk, not covered by umbilical

vessels, different small ducts non dissimilar from the rivulets of the

cicatricle were taking shape. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

19. - Sexti

superata die, taliter cubabat pullus in amnio A[56],

insigni pollens capite, cuius amplior vesicula B,

quasi gemina, oblonga excitata scissura, messoriae falci[57]

fortasse locum praebebat, et lacerata nullum reddebat ichorem.

Anteriores binae cerebri vesiculae C,

humiliores redditae, subcrescente carne, parum obscurabantur, quibus

appendebatur rostri inchoamentum: intercepta vero vesicula pene

latitabat; quod et quintae, in occipite locatae, accidebat. Spinalis

medulla, in binas divisa partes, solida per longum carinae

exporrigebatur. Alae, et crura, exporrectis pedibus D,

elongabantur. Abdomen E

clausum, quasi hernia laborans, extra protuberabat. Erumpentia

umbilicalia vasa F partim in tenue albumen G[58],

vitellum et amnion ambiens, partim in vitellum H

producebantur; et arteriae, graciliores redditae, venis ipsis

valde [9] minores erant. In abdomine, Iecoris evidentior structura emergere

incipiebat; reticularis namque compages I

observabatur ex vasis et involucris structuram firmantibus, quibus

miliares glandulae haerebant; et ita sensim spatia replebantur.

Dubitavi interdum, quod, sicuti in testibus et conglobatis glandulis,

exterius, et interius, musculosae carneaeque fibrae areas constituendo

firmant et comprimunt glandularum molem, ita in iecore eaedem reperiri

possint. Iecoris color nondum rubicundus, sed ex candido subfuscus

redditus erat. Cor interius conditum, licet mucosum, binis pulsabat

ventriculis, a quibus lacertosae pendebant auriculae, duplici

excitatae motu, mole adhuc insignes, una cum vasis candidis. Corporis

exterior habitus cute obductus, vasorum reticularibus propaginibus

irrigabatur, et evidentiores reddebantur tumores quidam, seu futurarum

pennarum folliculi. |

When

the 6th day was passed, the chick was

found laying in the amnion A (fig. 19) in this way: it was endowed

with a big head, whose almost doubled greater vesicle B, a lengthened

fissure having taken shape, perhaps offered space to the reaping hook

- the cerebral sickle or great sickle, and when lacerated it didn't

send forth any liquid. The two anterior cerebral vesicles C, having

lowered, were a little bit hidden by the growing flesh, and the sketch

of the beak was hanging on them. The interposed vesicle was almost

hidden, as it was happening also to the fifth vesicle located at the

occiput. The spinal marrow, divided into two parts, was extending

solid along the carina. The wings and the legs were lengthening and

the feet D were enlarged. The abdomen E, closed, was sticking outside

as suffering from hernia. The bursting umbilical vessels F were

distributed partly in the thin albumen G surrounding the yolk and the

amnion, partly in the yolk H; and the arteries, becoming thinner, were

much smaller than the veins themselves. In the abdomen the structure

of the liver started to emerge with greater evidence, and in fact was

observed the reticular structure I, composed of vessels and wraps

strengthening the structure, to which were sticking some small

formations similar to grains of millet; and so the spaces were

gradually filled. Sometimes I doubted that also in the liver the same

muscular and fleshy fibres are available identical to those that, as

in testicles and in compressed glands, outside and inside, by

delimiting some areas, are strengthening and compressing the glandular

mass. The colour of the liver was not reddish yet, but from snow-white

became rather dark. The heart, hidden more inside, although mucous,

pulsated with both ventricles, from which, together with white vessels,

some strong auricles were hanging, stimulated by a double movement and

increased in volume. The outside of the body, covered by skin, was

irrigated by reticular offshoots of vessels, and some protuberances

were becoming more evident, that is, the follicles of the future

feathers. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

20. - Septima terminata

die ita configuratus iacebat pullus: Capite amplo et insigni pollebat,

et cerebrum A etiam extra

eminebat solitis contentum indumentis; quibus laceratis ichor iam

fluidus in solida concreverat filamenta, ventriculorum concamerationes

excitantia. Inter

amplos oculos sensim erumpebat rostrum. Alae et crura cum appensis

pedibus omnimodam sortitae erant configurationem, et venter B

tumidus turgentibus visceribus reddebatur. Umbilicalia vasa foras

erumpentia, per vitellum et albumen producta elongabantur. Conclusum

intra thoracem Cor hanc servabat figuram; geminis sc. ventriculis,

quasi sacculis C contiguis, et in superiori parte unitis, cum superposito

auricularum corpore D

compaginabatur, et bini motus in ventriculis, totidemque in auriculis

succedebant; deorsum enim retractum fistulosum corpus, quod in

continuatas arterias sanguinem a dextro ventriculo receptum pulsu

propellebat, sinistrum ventriculum mole maiorem iam excitaverat: circa

utrosque musculosae spinales fibrae successive obducebantur, quibus

cordis caro compaginabatur, et ambo ventriculi nectebantur, et

ambiebantur. Auriculae et ipsae inaequales et rugosae ex lacertorum

suborta implicatione redditae, quasi novum corculum binis distinctum

cavitatibus constituebant; quod in adultis evidentius patet. Lacerata

cute, carnibus, et mucoso peritoneo, renes oblongi cinerei coloris

apparebant. Iecur ipsum, subluteo interdum suffusum colore, quandoque

cinereo, auctius et solidius reddebatur, et ipsius glandulae non

omnino rotundam et sphaericam referebant figuram, sed oblongiores et

quasi caecales utriculos, ductui hepatico appensos, representabant;

quod in aliquibus glandulosis hepatis racemis et miliaribus glandulis

frequenter observatur. Ventriculus

carnosus, licet adhuc exiguus, candidus erat, solitaque figura

constans; appensa habebat intestina gracilia et alba. |

When

the 7th day passed, the chick was

shaped in the following way. It was standing out for the wide and big

head, and also the brain A (fig. 20) was sticking out on the outside,

held by usual coverings; when they were lacerated the liquid, formerly

fluid, was consolidated in solid filaments forming the cavities of

cerebral ventricles. Among the big eyes the beak was slowly sticking

out. The wings and the legs, with the suspended feet, had reached

their complete conformation and the abdomen B was inflated by the

entrails that were increasing in volume. The umbilical vessels,

pushing their way outward, lengthened by extending themselves through

the yolk and the albumen. The heart, held in the thorax, maintained

the following appearance: that is, it was composed by two ventricles

as being two small contiguous bags and joined in the upper part, with

the overlap of the structure D of the auricles, and two movements

alternated in the ventricles and as many in the auricles. In fact the

tubular structure, that had lowered, with a pulsation pushed the blood

received from the right ventricle in the following arteries, and

already had stimulated the left ventricle that was greater in size.

Around both ventricles were branching in succession some muscular

spine-shaped fibres by which the flesh of the heart was made, and by

which both ventricles were linked and surrounded. The auricles, also

made unequal and wrinkled by the muscular neoformation, almost

constituted a new little heart divided in two cavities, which is more

evident in adult subjects. After the skin, the flesh and the mucous

peritoneum had been lacerated, the lengthened and ash coloured kidneys

were visible. The liver itself, sometimes suffused with yellowish

colour, other times ash coloured, was appearing bigger and more

consistent, and its structures didn't show a quite round and spherical

appearance, but they seemed small cavities rather lengthened, and

almost with blind bottom, hung on the liver duct, a thing often

observed in some clusters of liver structures and in glands structured

as grain of millet. The muscular stomach, although still small, was

white, it showed the usual shape and had hung the delicate and white

intestines. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

21. - Post

octavae diei incubationem

grandior redditus pullus capitis amplitudinem adhuc servabat, quo

aperto, cerebri moles iam solidior erat; nam vesiculae olim disparatae,

nunc unitae, geminas constituebant eminentias, in quibus ventriculi

excitabantur, thalamus pariter seu exortus nervorum opticorum, et

cerebellum cum principio spinalis medullae. Exterior

corporis habitus tuberculis A exasperabatur,

[10] a quibus pennae erumpebant, quae insigniores erant circa dorsum, et

uropygium. Umbilicus B latus

et amplus, ex amnii ambiente tunica, ultra sanguinea vasa, intestinula

(velut in hernia accidit) admittebat. In aperto abdomine Iecur

aeruginosum, in lobos divisum, soliditatem acquisierat; nondum tamen

recollecta observabatur bilis. Cor

de more pulsabat, et lateraliter pulmones candidi emergebant. |

After

the incubation of the 8th day the

chick, that became bigger, still kept a big head, and when opened, the

cerebral mass was by now more compact. In fact the vesicles, before

separated and now united, constituted two twin prominences in which

the ventricles were forming and also the thalamus, that is the origin

of the optic nerves, and the cerebellum with the beginning of the

spinal marrow. The outside of the body was made rough by the bulges A

(fig. 21) from which the feathers came out, that were more evident

around the back and the uropygial gland*. The navel B, wide and ample,

starting from the surrounding amniotic membrane, was housing, besides

the blood vessels, the small intestines (as it happens in a hernia).

In the abdomen, after was opened, the liver, rust in colour,

subdivided into lobes, had acquired solidity, but a collection of bile

was not yet perceived. The heart pulsated as usual and at its sides

the white lungs were standing out. |

|

|

|

|

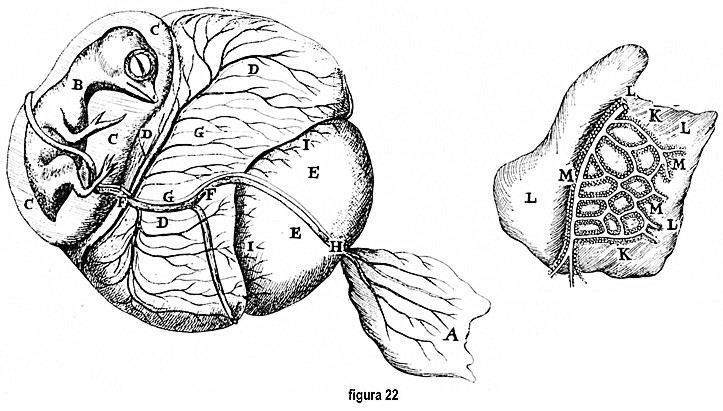

Fig.

22. - Decima

elapsa die, pullus ita cubabat, et ambientibus humoribus nectebatur:

Laceratis membranis, totum ovum circum-vestientibus, et praecipue

crassiori A, quae albuminis fusiorem continebat, corii instar, substantiam,

talis occurrebat species: Pullus B

ita flexo corpore iacebat, innatans in humore C,

propria tunica[59]

contento. Subsequebatur

continuatum vitelli involucrum D[60],

cui appendebatur seu arcte haerebat crassior albuminis portio E.

Singula haec venas F, et

arterias G, umbilicales

recipiebant; lata enim vena H

in tenuioris albuminis tunicam A[61]

deducebatur: Vitelli quoque tunica D

venas et arterias recipiebat, quae non omnino totam ipsius peripheriam

contegebant, sed relicto rotundo spatio[62],

quasi pupilla, qua crassiori albumini nectebatur, exiguos surculorum

fines I in huiusmodi crassum

albumen promebant. Elegantem circa vitellum productionem mirari

licebat, dum evacuata huiusmodi tunica, et, diductis parum ipsius

partibus, supra vitrum extendebatur. Arteriae mole minores erant ipsis

venis, illae vero nequaquam perpetuo vitelli tunicae haerebant, sed

elongatis extremitatibus invicem anastomizatis, caecas quasi

appendices K premebant, quae

a tunica L interius

pendentes in vitelli ichore fusco innatabant, et mergebantur. Arteriis

praecipue copiosi haerebant sacculi M,

qui ambientibus sanguineorum vasorum rivulis firmabantur, et

conglobata vitelli substantia turgebant: singulus utriculus plures

globulos parum depressos continebat. Venarum et arteriarum

umbilicalium rami nequaquam perpetuo unitim excurrebant, sed parum

distantes elongabantur; et caecales arteriarum appendices a venis

transversales surculos recipiebant. Vitelli ichor iam fluidior

redditus subflavus, lentusque erat, et parum mole imminutus videbatur,

multumque defecisse tenuior

albuminis portio deprehendebatur. Pulli exterior habitus, alae praecipue et

uropygium, costulis et musculis firmabantur, et pennis erumpentibus

condecorabantur. Rostrum iam osseum reddebatur; scutum enim pendebat,

cuius angularis portio, centrum occupans, primo candidam et osseam

acquisierat naturam, hancque hexagonum quoddam fusci coloris corpus

continebat, quod et ipsum quasi carnea consimili substantia ambiebatur.

Oculi velamentis, et membrana, qua nicticant, contegebantur. Interius

rubiginoso Iecori appensus pendebat Bilis folliculus, quae caerulea

erat. Ventriculus carnosus una cum elongatis intestinis, rite

configuratis, interdum abdominis cavitatem occupabat, quandoque extra

pendebat; et in ventriculo nil deprehendebatur, in proximo vero

intestino parum bilis stagnabat. |

When

the 10th day passed, the chick was

laying in the following way and was connected with the surrounding

liquids. After the membranes wrapping the whole egg were lacerated,

and above all the thickest A (fig. 22) that, as if made of leather,

contained the more fluid substance of the albumen, the following scene

occurred: the chick B was laying so, with the flexed body, swimming in

the liquid C contained in its own membrane. Underneath was following

the uninterrupted wrap D of the yolk, to which was suspended or

tightly stuck the more dense part E of the albumen. Every one of these

structures received the umbilical veins F and arteries G. In fact a

wide vein H went to end in the membrane A of the more fluid albumen.

Also the membrane D of the yolk received veins and arteries that

however didn't cover entirely its whole periphery, but, leaving a

round space free, almost as a pupil through which was linking to the

more dense albumen, they sent thin endings of little vessels I into

this dense albumen. Around the yolk it was possible to admire an

elegant prolongation of them when, after such membrane had been

emptied, it was stretched above a glass after having divaricated its

parts a little bit. The arteries were of smaller dimensions in

comparison to the veins and they didn't always stick at all to the

membrane of the yolk, but, through lengthened extremities anastomosed

each other, they dug as blind appendixes K that, internally hanging

from the membrane L, were swimming and plunging into the dark liquid

of the yolk. Numerous small sacks M mainly stuck to the arteries, and

they were strengthened by the surrounding rivulets of the blood

vessels and they were bulging because of the accumulated substance of

the yolk. Every wrap contained numerous small round and not very

crushed formations. The branches of the umbilical veins and arteries

didn't flow at all always placed side by side, but remained a little

bit distant, and the blind appendixes of the arteries received some

transversal little vessels from the veins. The liquid of the yolk,

already more fluid, was yellowish and viscous and seemed a little bit

reduced in volume, and it was seen that the thinner portion of the

albumen was strongly decreased. The external appearance of the chick,

above all the wings and the uropygial gland, were consolidated by

small ribs and by muscles and they were embellished by sprouting

feathers. The beak became already bony; in fact a shield was hanging

whose angular part occupying the centre had for the first time

acquired a white and bony appearance, and a hexagonal body dark in

colour contained this part, and also it was surrounded by an almost

fleshy similar substance. The eyes were covered by voiles and by the

nictitating membrane. Inside the rust coloured liver the pouch of the

blue bile was suspended and hanging. The muscular stomach, together

with the bowels that had lengthened and had normal appearance,

sometimes was occupying the cavity of the abdomen, other times was

hanging outside. And in the stomach nothing was found, while in the

following bowel a little bit of bile was stagnant. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

23. - Post

duodecimam diem Pennarum

eruptiones A, dorsi

longitudinem contegebant, et ab extremis pariter alis B

et coxis C erumpebant;

subiectae vero partes quasi implumes erant. In ventre hiatus adhuc aderat,

[11] quo

umbilicalibus D patebat aditus, et quandoque etiam intestinis, et carnoso

ventriculo. Fellea cistis, ab amplo iecore pendens, viridi turgebat

humore, cuius portio in proximum intestinum eructabatur. Intestinulum

a carnoso ventriculo erumpens glandularum[63]

inchoamenta continebat. Pulmonum

pariter compages emergebat, solidefactis costulis, et exterius

extensis musculis. |

After

the 12th day the sprouted feathers A

(fig. 23) were covering the length of the back, and likewise they

sprouted from the end of wings B and thighs C, while the ventral areas

were almost unfledged. In the abdomen was still present an opening

through which the access to the umbilical vessels D was opening and

sometimes also to bowels and muscular stomach. The gall bladder,

hanging from the big liver, was bulging with a green liquid, part of

which was flowing in the nearby intestine. The small intestine

emerging from the muscular stomach contained sketches of glands. Also

the structure of the lungs was evident, the small ribs were

consolidated and externally the muscles were expanded. |

|

|

|

|

Fig.

24. - Decima quarta die transacta, iam fere perfectus erat pullus;

pennae A auctiores et

copiosiores eminebant; musculosa caro sub cute turgebat; ossa fere

soliditatem adepta erant; viscera clauso quasi abdomine debitam

circumscriptionem sortiebantur; felleus folliculus subviridis interdum,

quandoque caeruleus, a iecore pendebat, quod pertranseunti umbilicali

venae parum continuabatur: In carnoso ventriculo lac stagnabat, et

proxima intestini portio muco quodam candido replebatur, glandulaeque

copiosae[64]

intra eiusdem substantiam, interserebantur. Cor B

unitis ventriculis compaginabatur, et plures arteriae C[65] tubuli, veluti manus

digiti, olim a corde distantes, iam immediate haerebant; Auriculae D

pariter amplae et impense rubicundae lacertis componebantur

reticulariter implicitis, ita ut areae et spatia diversi coloris

cernerentur. |

When

the 14th day passed, the chick was

already almost completed. The feathers A (fig. 24) were sticking out

greater and more numerous, the muscular flesh was swollen under the

skin, the bones had almost reached the compactness, the entrails, the

abdomen being almost closed, had a right delimitation, the gall

bladder, sometimes greenish sometimes blue, was hanging from the liver,

which was loosely linked with the umbilical vein crossing it. In the

muscular stomach some milky juice was stagnating and the nearby

portion of the bowel was full of a white mucus, and numerous glands

were disseminated in its structure. The heart B was composed by the

ventricles joined each other, and numerous arterial little ducts C, as

fingers of a hand, before distant from the heart, now were tightly

sticking to it. The auricles D, equally wide and intensely red, were

composed by tortuous muscles arranged as net, so that areas and spaces

of different colour were perceived. |

|

Singula

haec manifestiora magisque firma reddebantur absumptis humoribus,

praecipue utroque albumine, et quasi dimidia vitelli portione, tribus

decorrentibus hebdomadis, quo tempore in lucem proditurus erat pullus,

qui adhuc inclusus pipiens audiebatur. Huius carnosus ventriculus

concreto turgebat succo quasi lacte vel oxygala: superior intestinorum

portio subviridi succo, inferior autem cinereo replebatur humore, et

ab hiante vitelli brevi ductu liquorem recipiebat; extrema vero

intestina cum binis appensis caecis stercoraceo humore inficiebantur.

In abdomine exterius carnosa quaedam labia patentem umbilici hiatum

constituebant, quo admittebatur umbilici portio extra pendens;

funiculus enim quasi nerveus erumpebat, qui sanguineis vasis

spiraliter ductis[66]

circumambiebatur. In corii[67]

cavitate reticularis alborum ductuum plexus quasi gracile omentum

observabatur, mucosa et candida aspersum substantia: Adhuc ambigo, an

eius ope albuminis portio versus foetum deducatur, an vero sit

chalazarum vestigium? Vitelli folliculus ichore semiplenus intra

abdominis claustra custodiebatur. |

Everyone

of these structures was becoming more apparent and more solid after

the disappearance of the liquids, above all of the two albumens and of

almost half the yolk, three weeks being passed, the moment when the

chick was about to come to the light, and still shut up it was heard

peeping. Its muscular stomach was turgid of a dense juice similar to

milk or to sour milk. The upper portion of the bowels was full of

greenish juice, while the lower was full of an ash coloured liquid and

was receiving liquid from the short duct of the yolk that was open.

The terminal portions of the bowels, with both caecal appendixes, were

full of a stercoraceous liquid. Externally, at abdomen level, some

fleshy lips delimited the gaping opening of the navel, through which

was entering the portion of the navel hanging outside: in fact a

funicle similar to a nerve, surrounded by spirally shaped blood

vessels, was coming out. In the cavity of the chorion a reticular