Lessico

Francisco Álvares

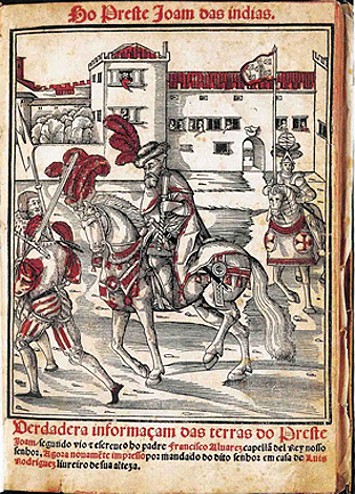

Frontispício da Verdadeira Informaçam das Terras do Preste Joam das Índias, segundo vio e escreueu ho padre Francisco Alvarez capellã el Rey nosso senhor. Lisboa, Casa de Luis Rodriguez, 1540.

Álvares Francisco:

sacerdote, viaggiatore e cronista portoghese (Coimbra ca. 1490 - Roma ca.

1540). Prese parte come cappellano alla spedizione portoghese in Etiopia

(allora detta Abissinia), comandata prima da Duarte Galvão e poi da Rodrigo

de Lima (1515-1527). Per incarico del Papa redasse la relazione del viaggio,

con numerose notizie storiche e geografiche sull’Etiopia che va sotto il

nome diVerdadeira informação do Preste João das Índias

(Notizia veritiera sul Prete Gianni delle Indie![]() ), il cui nome più per esteso

suona così: Ho Preste Joam das Indias! Verdadera informaçam das

terras do Preste Joam segundo vio e escreveo ho padre (…) capellã del Rey

nosso Senhor. Agora novamete impresso por mandado do dito senhor em casa de

Luis Rodrigues... aos vinte e dous dias de Outubro de mil & quinhentos

& quarenta annos.

), il cui nome più per esteso

suona così: Ho Preste Joam das Indias! Verdadera informaçam das

terras do Preste Joam segundo vio e escreveo ho padre (…) capellã del Rey

nosso Senhor. Agora novamete impresso por mandado do dito senhor em casa de

Luis Rodrigues... aos vinte e dous dias de Outubro de mil & quinhentos

& quarenta annos.

Ulisse Aldrovandi

a

pagina 298![]() del II volume di Ornitologia riferisce quanto segue: Francisco Álvares in Verdadeira informação do Preste João das

Índias narra che le galline messe in tavola, la cui carne era stata

spogliata della pelle nonché delle ossa e poi farcita di svariati aromi

delicati, erano poi state sistemate con tanta abilità che in nessun punto

traspariva un’area o una traccia di lacerazione.

del II volume di Ornitologia riferisce quanto segue: Francisco Álvares in Verdadeira informação do Preste João das

Índias narra che le galline messe in tavola, la cui carne era stata

spogliata della pelle nonché delle ossa e poi farcita di svariati aromi

delicati, erano poi state sistemate con tanta abilità che in nessun punto

traspariva un’area o una traccia di lacerazione.

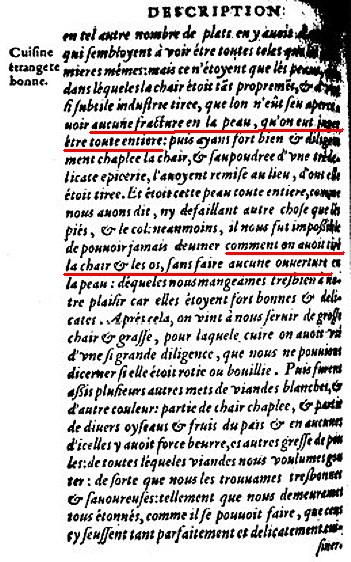

Ecco la traduzione francese del testo di Francisco Álvares relativa a queste galline. Si tratta del capitolo 100 di Historiale description de l'Ethiopie contenant vraye relation des terres, & païs du grand Roy, & Empereur Prete Ian etc. edito ad Anversa nel 1558. Alla versione francese fa seguito quella italiana contenuta in Navigazioni e Viaggi (1550) dell'umanista, geografo e storico italiano Giovanni Battista Ramusio (Treviso 1485 - Padova 1557), dove Álvares suona Alvarez.

Giovanni Battista Ramusio

Navigazioni e Viaggi – 1550

Viaggio

in Etiopia di Francesco Alvarez

1540

Cap. C. – Della pratica che ebbe l'ambasciadore col Prete sopra li tappeti, e come il Prete gli fece un solenne convito che durò fino a mezzanotte.

Le vivande erano fatte di diverse carni variamente acconcie quasi al modo nostro, fra le quali erano galline intere grandi e grasse, parte lesse e parte arroste; e in altritanti piatti venivano altretante galline che parevano quelle medesime, ma erano sole le pelli, in questo modo, che eglino avevano cavata fuori la carne e tutte l'ossa con somma diligenza, di modo che la pelle non era rotta in alcuna parte ma era tutta intera, e poi tagliata la carne sottilmente e mescolata con alcune spezierie delicate, e l'avevano di novo ripiena con essa: la quale, come è detto, era tutta intera, né vi mancava altro che il collo e li piedi dalle ginocchia in giú, né mai potemmo considerare come potessero cavar fuori la carne e l'ossa, o vero scorticarli, che non vi si vedesse rottura alcuna. Di queste mangiamo molto bene a nostro piacere, perché erano molto delicate e buone.

Álvares, Padre Francisco (Coimbra c.1470? - Roma c.1540). Historiador português, natural de Coimbra. Presbítero, foi um dos principais autores da historiografia de viagens de Quinhentos. Nasceu em Coimbra por volta de 1470. Em 1515 foi enviado pelo rei D. Manuel, de quem era capelão, numa embaixada à Etiópia (então designada por Abissínia) liderada por Duarte Galvão, embaixador que viria a falecer, sendo substituído por D. Rodrigo de Lima. Foi já na companhia deste que, em 1520, entrou na corte do imperador da Etiópia, país onde permaneceu durante seis anos e onde reuniu os materiais para a sua obra Verdadeira Informação das Terras do Preste João (1540). Esta obra inaugurou o ciclo sobre a Etiópia, e nela o Padre Francisco Álvares descreveu com minúcia e exactidão tudo aquilo que observou durante a sua estadia: as aventuras do percurso efectuado em caravana, a estada na corte do negus (título dos soberanos etíopes da época), povos e locais desconhecidos, com a sua flora e fauna características, a vida doméstica, o vestuário, os rituais sociais e religiosos, o armamento, e tudo o mais que lhe foi permitido observar. O sucesso e o carácter inovador do seu livro foram de tal ordem que, nos anos seguintes, seria traduzido para castelhano, francês, inglês, alemão e italiano. Em 1527, regressou a Portugal. Quatro anos depois, em 1531, partiu em nova embaixada, desta feita a Roma, na companhia do monge Zagazabo, enviado pelo negus (que os portugueses designavam por Preste João das Índias, figura mítica que se acreditava ser o soberano de um reino cristão, cuja localização foi alvo de várias especulações) para prestar obediência ao Papa Clemente VII. Permaneceu em Roma até à data da sua morte.

www.universal.pt

As vagas

noções espaciais

de Ásia, Índia e Etiópia

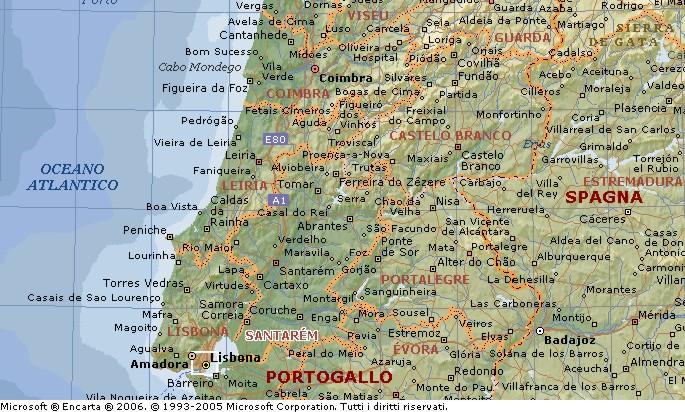

Sobre a expansão do significado de Índia e de Ásia, é significativo o que escreve Oliveira Marques: “A geografia medieval punha a Ásia a começar no Nilo, e não no Mar Vermelho, incluindo portanto nela a maior parte da moderna Etiópia. Alargava também o sentido da palavra “Índia”, parte da qual englobava o nordeste da actual África. Havia várias “Índias” e numa delas vivia o grande imperador cristão, governando um vasto território, densamente povoado, imensamente rico e espantosamente poderoso. Era conhecido como o Preste João, visto ser ao mesmo tempo padre (presbítero) e rei.” (marques, a. h. de Oliveira. História de Portugal. Lisboa: Palas Editores, 1985, v. I, p. 242.)

É dentro desse sentido que se compreende por que o livro do Padre Francisco Alvares sobre a presença dos portugueses na Etiópia se chame Ho Preste Joam das Indias! Verdadera informaçam das terras do (...) (Ho Preste Joam das Indias! Verdadera informaçam das terras do Preste Joam segundo vio e escreveo ho padre (…) capellã del Rey nosso Senhor. Agora novamete impresso por mandado do dito senhor em casa de Luis Rodrigues... aos vinte e dous dias de Outubro de mil & quinhentos & quarenta annos).

Entre 1155 e 1175 circulou pela Europa uma carta assinada pelo Preste João, que se autodenomina Imperador das Índias. O primeiro a receber tal carta foi o imperador do Oriente, Manuel Comeno. Sabe-se que essa carta era falsa, provavelmente uma sátira aos bizantinos onde, pelo contraste, mostrava-se o quanto o Império estava longe de um reino ideal como o do Preste. Hilário Franco Júnior no capítulo denominado “A utopia da justiça; o milênio”, fala de seis personagens medievais consideradas messiânicas, chefes capazes de trazer ao mundo um tempo de justiça e de paz — as promessas messiânicas do reino. Esses Messias são: o rei Artur, Carlos Magno, Frederico Barba Ruiva, o Preste João, o imperador Frederico II, que era visto por uns como Messias, por outros como o Anticristo, e Luis VII ou Filipe Augusto, da França.

Sobre a quarta personagem, o Preste João, escreve Hilário Franco Júnior: Um quarto personagem a considerar é o Preste João, visto como descendente de Davi, conseqüentemente figura carregada de sentido cristológico e escatológico. Duplo sentido reforçado pelas descrições que faziam dele uma mescla de seu homônimo apóstolo João (que por uma lenda então em voga não estaria morto e sim preparando a guerra ao Anticristo), do típico rei-sacerdote do Antigo Testamento, Melquisedec, e do Imperador dos Últimos Tempos. Por tudo isso, Preste João ou um descendente dele estava encarregado de vigiar as poderosas portas de ferro que no Cáucaso aprisionavam 22 povos impuros, dentre eles os bíblicos Gog e Magog. Com efeito, desde fins do século V uma tradição oral referia-se àquelas portas e àqueles aprisionamentos, que teriam sido realizados por Alexandre Magno.

Em algum momento da Idade Média, passou-se a acreditar que por detrás daquelas portas estariam também as famosas dez tribos desaparecidas de Israel como registrava contemporaneamente ao mito do Preste João, a popular Historia Scholastica. O entrecruzamento daquelas duas tradições escatológicas expressa bem a preocupação da época. A cristandade dependia do Preste João para não ser destruída antes do tempo, tema que sensibilizava naquele contexto de pressão muçulmana sobre os Estados Cruzados do Oriente Médio.

De acordo com Hilário Franco Junior, a condição messiânica do Preste João se reforça pela sua vinculação mítica com outras figuras bíblicas, que são também símbolos de uma totalidade: o rei-sacerdote Melquisedec, visto pela exegese como uma prefiguração de Cristo; os Reis Magos, que estavam associados aos três filhos de Noé [Sem, Cam e Jafet], origem das três raças — a iconografia medieval e posterior representa um dos reis como negro.

A partir da carta enviada ao Imperador de Bizâncio, os europeus passaram a acreditar na existência desse poderoso imperador cristão e de seu fabuloso império. Essa primeira carta, aliás, se mostrava como um resumo de todas as fantasias do imaginário europeu da Idade Média; havia nela espaço para a torre de Babel, o Paraíso Terrestre, a ave Fênix, o Unicórnio etc. Além disso, tão poderoso monarca cristão representava a possibilidade de derrotar de vez os infiéis e libertar a cidade santa de Jerusalém.

É nesse contexto que se pode melhor compreender a procura do Preste João como uma das causas das navegações portuguesas. Encontrar esse forte aliado para a luta contra os mouros seria um poderoso trunfo para a política externa do reino de Portugal. O Infante D. Henrique, D. João II e D. Manuel mandaram procurar o Preste. Havia ordem expressa no sentido de as expedições que percorriam o litoral africano adentrarem os rios em busca do Preste.

Oliveira Marques historia: Sabe-se hoje que o conceito medieval de “Preste João”, (cujo nome parece derivar de zan hoy, “meu senhor”, forma como os etíopes se dirigiam a seu rei) fundia e confundia diversas tradições e informações relativas a três núcleos de cristãos distintos e de várias entidades e realidades políticas: o reino cristão-monofisita da Abissínia ou Aksum, as comunidades cristãs-nestorianas da Ásia Central, e os grupos nestorianos espalhados pela Índia.

No século XV, conseguira-se já informação mais exacta acerca do Preste João, depois de alguns contactos directos tentados e obtidos de ambas as partes. O que permanecia objecto de grande controvérsia era a maneira de chegar à Etiópia por via de sudoeste ou de ocidente, continuando também a saber-se pouco do efectivo poder e riqueza do Preste João.

brani tratti da www.letras.puc-rio.br

Textos e

mapas europeus

sobre a Etiópia dos séculos XVI-XVII

Uma das particularidades da literatura europeia sobre o reino abissínio é o modo como as descrições de viagem e exploração geográfica se mesclam com representações lendárias. A publicação de obras como o Fides, Religium, Moresque Ethiopum, por Damião de Góis e sobretudo a Verdadeira Informação das Terras do Preste João, em 1540, foram importantes marcos para o aprofundamento do conhecimento europeu sobre aquele país. Mas suscitaram também uma renovação do imaginário fantástico sobre o "reino do Preste João". Este é manifestamente o caso da polémica obra do frade dominicano Luis de Urreta, Historia... de los Grandes y Remotos Reynos de la Etiopía, de 1610. Este autor valenciano fantasiava aí sobre uma suposta antiga presença dominicana num país maravilhoso, numa sociedade virtuosa e católica, de matizes claramente utópicos. Os padres jesuítas, que detinham o exclusivo da missionação católica numa Etiópia que descreviam como herética e bárbara, reagiram fortemente a esta obra que questionava a legitimidade da sua presença ali. Com base nas cartas ânuas enviadas para a sede da Companhia de Jesus, o Padre Fernão Guerreiro publicou, em 1611, uma primeira refutação da obra de Luis de Urreta (a Adição à Relação de Etiópia), logo seguido, em 1615, pelo livro de Nicolau Godinho, De Abassinorum Rebus. A mais sistemática refutação da visão utópica do frade dominicano, no entanto, é a monumental monografia do jesuíta espanhol Pero Pais (Pedro Páez), a História de Etiópia, completada em 1622, e mantida inédita por decisão dos superiores da Companhia. Este relato vívido da etnografia etíope, da história da missão jesuíta e das aventuras do autor nas terras abissínias, e da sua visita às fontes do Nilo Azul (Abbai) manteve-se inédito até ao início do séc. XX. Foi posteriormente reescrita (e também não publicada) por outro padre da missão etíope, Manuel de Almeida, que, recuperando as informações de Pais sobre a Etiópia, reduziu o peso da sua refutação de Urreta. Já após a restauração da independência de Portugal, um outro padre jesuíta, Baltazar Teles, publicou uma versão totalmente reformulada do livro de Almeida. O manuscrito de Manuel Almeida contém um mapa detalhado do território etíope, que serviu de base a Teles e a Iob Ludolf, contribuindo assim para uma revisão profunda do imaginário geográfico europeu sobre a Etiópia. A cartografia da Etiópia reduz-se então para dimensões topograficamente correctas, e deixa de comportar imagens de palácios fantásticos, dos montes da lua e de um lago central africano de onde fluíam, nos mapas precedentes, não apenas o Nilo, mas o Zambeze, o Níger, o Senegal e o Congo. Ainda assim, mesmo num espaço subitamente redimensionado, as conexões fantásticas da Etiópia com o reino lendário do Preste João não desaparecem, apenas se transformam. Samuel Johnson, em meados do séc. XVIII, ao traduzir para inglês o texto de um outro missionário, o Padre Jerónimo Lobo, e sobretudo ao publicar o romance Rasselas, relançou a visão de um reino utópico, perdido nas terras altas do Corno de África. Por outro lado, a busca do lago central africano perdurará até meados do séc. XIX, e motivará as explorações de Burton, Beke e Livingstone.

http://pwp.netcabo.pt

Francisco Álvares (c. 1465 – c. 1540) was a Portuguese missionary and explorer. Born in Coimbra, Portugal, as an adult he was a chaplain-priest and almoner to King Manuel I of Portugal. He was sent in 1515 as part of an embassy to the Emperor of Ethiopia, accompanied by the Ethiopian ambassador Mattheus. Their first attempt to reach the port of Massawa failed due to the actions of Soares de Albergaria, governor of Portuguese India , which got no closer than the Dahlak Archipelago and led to the death of the Portuguese ambassador Duarte Galvão at Kamaran. Álvares and Mattheus were forced to wait until the arrival of Soares' replacement, Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, who successfully sent the embassy on, with Dom Rodrigo de Lima replacing Duarte Galvão. The party at last reached Massawa on April 9, 1520, and reached the court of Lebna Dengel where he befriended several Europeans who had gained the favor of the Emperor, which included Pêro da Covilhã and Nicolao Branceleon. Father Álvares remained six years in Ethiopia, returning to Lisbon in either 1526 or 1527.

In 1533 he was allowed to accompany Dom Martinho de Portugal to Rome on an embassy to Pope Clement VII, to whom Father Álvares delivered the letter Lebna Dengel had written to the Pope. The precise date of Francisco Álvares death, like that of his birth, is unknown, but the writer of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article concludes it was later than 1540, in which year an account of his travels were published at Lisbon. In the introduction of their translation of Álvares work, C.F. Beckingham and G.W.B. Huntingford furnish evidence that points to Álvares death in Rome, and admit that he may have died before his work was published.

In 1540, Luís Rodrigues published a version of Álvares account in a one

volume folio, entitled Verdadeira Informação das Terras do Preste João

das Indias ("A True Relation of the Lands of Prester John of the

Indies![]() "). C.F. Beckingham and G.W.B. Huntingford cite evidence, based in

part on the earlier work of Professor Roberto Almagia, showing that Rodrigues's

publication is only a part of Álvares's entire account. Another version of

what Álvares wrote was included in an anthology of travel narratives, Navigationi

et Viaggi assembled and published by Giovanni Battista Ramusio, and

published in 1550. Almagia also identified three manuscripts in the

Vatican Library which contain versions of excerpts from the original

manuscript.

"). C.F. Beckingham and G.W.B. Huntingford cite evidence, based in

part on the earlier work of Professor Roberto Almagia, showing that Rodrigues's

publication is only a part of Álvares's entire account. Another version of

what Álvares wrote was included in an anthology of travel narratives, Navigationi

et Viaggi assembled and published by Giovanni Battista Ramusio, and

published in 1550. Almagia also identified three manuscripts in the

Vatican Library which contain versions of excerpts from the original

manuscript.

Francisco Álvares work has been translated into English at least twice. The first time was the work of the ninth Baron Stanley of Alderley for the Hakluyt Society in 1881. This translation was revised and augmented with notes by C.F. Beckingham and G.W.B. Huntingford, The Prester John of the Indies (Cambridge: Hakluyt Society, 1961).

The author of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article was critical of the information it contained, believing it should "be received with caution, as the author is prone to exaggerate, and does not confine himself to what came within his own observation." However, Beckingham and Huntingford have a much higher opinion of Álvares testimony, stating that not only is it "incomparably more detailed than any earlier account of Ethiopia that has survived; it is also a very important source for Ethiopian history, for it was written just before the country was devastated by the Muslim Somali and pagan Galla invasions of the second quarter of the sixteenth century." He provides the first recorded and detailed descriptions of Axum and Lalibela. They continue:

He is sometimes wrong, but very rarely silly or incredible. He made a few mistakes; he may well have made others that we cannot detect because he is our sole authority; when he tried to describe buildings his command of language was usually inadequate; he is often confused and obscure, though this may be as much his printer's fault as his own; his prose is frequently difficult to read and painful to translate; but he seems to us to be free from the dishonesty of the traveller who tries to exaggerate his own knowledge, importance, or courage.

Francisco Álvares (* um 1465 in Coimbra; † um 1540 wahrscheinlich in Rom) war ein portugiesischer Missionar und Entdeckungsreisender. Álvares erhielt eine Ausbildung zum Priester. Im Jahre 1515 nahm er an einer diplomatischen Mission an den Hof des äthiopischen Kaisers, des Negus Lebna Dengel, teil. Die Großmutter Lebna Dengels, Kaiserin Eleni, richtete ein Hilfegesuch an den König Manuel I. von Portugal, da Äthiopien zu der Zeit durch die Türken des Osmanischen Reiches bedroht wurde. Die Gesandtschaft, eine gemischte Truppe aus Soldaten und Missionaren, angeführt von Dom Rodrigo de Lima, erreichte erst 1520 über Indien und den Hafen Massaua, Äthiopien.

Die Gesandtschaft blieb rund 6 Jahre in Äthiopien. 1533 überbringt er in Rom ein Schreiben des Negus an Papst Clemens VII.. In einem erstmals 1540 erschienen Buch ("Verdadeira Informação das Terras do Preste João das Indias", "Wahrhaftiger Bericht aus dem Reich des Priesters Johannes von Indien") berichtet Francisco Álvares über seinen Aufenthalt am Hofe des Negus und gibt erstmals dem christlichen Abendland einen Einblick in das christliche Äthiopien.

Francisco Alvarez

Alvarez Francisco († 1533/42), portugiesischer Entdeckungsreisender. - Der aus der Gegend von Cintra in Portugal stammende Franziskaner war Kaplan des portugiesischen Königs und Benefiziat von San Justa in Coimbra. 1517 wurde er von König Manuel I. als Begleiter der Gesandtschaft Duarte Galvaos zugeordnet, die auf Ersuchen der Kaiserin Elleni das Reich des sagenhaften Priesterkönigs Johannes in Indien aufsuchen sollte. Infolge des Todes Galvaos erreichte die Gesandtschaft jedoch nicht ihr Ziel. Der neue indische Vizekönig Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, der 1518 mit einer Flotte nach Indien gekommen war, betraute 1520 Rodrigo de Lima mit dem Auftrag. Die aus 18 Personen bestehende Gesandtschaft mit Alvarez erreichte im April 1520 den Hafen Massaua, von wo sie ins Landesinnere aufbrach. Der Bote Mateus, der von Äthiopien über Indien nach Portugal und von dort wieder zurück nach Äthiopien gereist war, starb kurz nach der Ankunft. Die Gesandtschaft unter der Führung von Rodrigo de Lima zog über Debarwa und Aksum, den Haik-See und Debre Libanos nach Taguelat, wo sie am 19.11. 1520 den Negus Lebna Dengel erreichte, der jedoch erklärte, nicht er, sondern die mittlerweile entmachtete Kaiserin Elleni habe den Boten nach Portugal geschickt. Es kam somit nicht zum Abschluß eines Bündnisses. 1521 wollte die Gesandtschaft nach Portugal zurück, wartete jedoch vergeblich an der Küste auf ein Schiff. Erst Ende April 1526 konnte die Gesandtschaft Äthiopien verlassen. - Alvarez verfaßte nach der Reise einen höchst wertvollen Reisebericht, der 1540 in gekürzter Version unter dem Titel "Ho Preste Joam das indias. Verdadera informacam das terras do Preste Joam" in Lissabon erschien. Eine wertvolle Hilfe für Alvarez war der seit ca. 1494 in Äthiopien lebende Portugiese Pero da Covilham, der ihm als Dolmetscher diente. Alvarez beschrieb zunächst die Reise bis zum Hof des Negus in der Art eines Itinerars. Wahrscheinlich entstand ein Teil der Aufzeichnungen bereits in Äthiopien selbst. Angesichts der Tatsache, daß der Imam Ahmed Granj ("der Linkshänder") zwischen 1531 und 1543 einen großen Teil Äthiopiens zerstörte, kommt dem Bericht etwa über die Kathedrale von Aksum besondere Bedeutung zu. Für mehr als ein Jahrhundert blieb der Bericht des Minoriten die wichtigste Quelle über Äthiopien. Er beschrieb als erster Europäer die Felsenkirchen von Lalibela, den Zway-See im Süden des Reiches, die Verhältnisse in Eritrea, das muslimische Reich "Dangalli" (Danakil) und "Adea" (Hadya) sowie "Damute" (Damot) und "Goyame" (Godjam), wo der Nil entspringe. Die Gespräche mit dem Negus und dem Abuna Markos vermittelten einen tiefen Einblick in die äthiopische Kultur. Sein besonderes Interesse galt den Ritualen der Kirche, besonders der Taufe und Beschneidung sowie der militärischen Ausrüstung des Landes. Der Negus erzählte ihm auch die Geschichte von der Abstammung der Kaiser von Salomon und der Königin von Saba. Eine Fülle topographischer Namen wird hier erstmals genannt. Leider ist die Originalhandschrift verloren; drei vatikanische Handschriften enthalten teilweise vollständigere Fassungen in italienischer Übersetzung. Briefe des Negus an den Papst und den König von Portugal wurden als Anhang dem Reisebericht zugefügt. Der Bericht über die "monophysitische" Kirche in Äthiopien ist weit entfernt von der Intransigenz, die man zur Zeit des Konzils von Trient gegenüber den "Schismatikern" zeigte. Er kritisierte jedoch die alttestamentlichen Praktiken wie Beschneidung und Einhaltung des Sabbats sowie die mangelnde Bildung des Klerus. - Über Goa und Cochin kehrte die portugiesische Flotte im Juli 1527 mit dem äthiopischen Priester Zagazabo nach Lissabon zurück. Der König empfing die Gesandten in Coimbra; Äthiopien aber hatte für Portugal mittlerweile an strategischer Bedeutung verloren. Alvarez wollte zum Papst, aber der König ließ ihn nicht ziehen; 1529 erhielt er eine Pfründe in der Erzdiözese Braga. Der dortige Erzbischof Diego de Sousa übergab Alvarez einen Fragenkatalog über Äthiopien; die Antwort darauf wurde an den Reisebericht angehängt. Mehrfach ersuchte Alvarez den König, dem Papst endlich die Obödienzerklärung des Negus überbringen zu können. Erst Ende Mai 1532 bevollmächtigte König Johann III. von Portugal Alvarez, Papst Clemens VII. das Schreiben des Kaisers zu übergeben. Am 29.1. 1533 trug der Minorit in Bologna in Anwesenheit Kaiser Karls V. seinen Bericht vor. Bereits im Februar 1533 erschien in Bologna ein Bericht über die Gesandtschaft im Druck; noch im gleichen Jahr erschien eine deutsche Übersetzung. Der portugiesische Gesandte Dom Martinho betrieb die Übersetzung des Werkes von Alvarez durch Paolo Giovio ins Lateinische. Obwohl der Negus den Papst gebeten hatte, Alvarez als Bischof zu schicken, erhielt dieser kein Bistum und kehrte auch nicht mehr nach Portugal zurück. Er starb zwischen 1533 und 1540/42 in Rom. Die Buchausgabe von 1540 wurde wahrscheinlich ohne sein Wissen von Luis Rodriguez in Lissabon publiziert. 1550 verwertete der Humanist Ramusio den Bericht von Alvarez bei seiner Neuausgabe der "Navigatione et Viaggi". 1556 erschien eine französische Übersetzung in Lyon, 1557 eine spanische in Anvers, 1566 eine deutsche bei Joachim Heller in Eisleben, die 1567 und 1573 neu aufgelegt wurde; 1576 erschien ein Neudruck in Frankfurt. 1581 erschien das Werk in der "General Chronica" bei Sigmund Feyerabend in Frankfurt. Alvares' Bericht über Äthiopien führte zur Beendigung der Periode, in der man in Europa nur unklare Vorstellungen vom "Reich des Priesterkönigs Johannes" hatte; die Entmythologisierung hatte jedoch auch zur Folge, daß das Interesse an Äthiopien in Europa abnahm.

Quellen: Die reiß zu deß ... Königs in hohen Ethiopien, den wir Priester Johann nenen, Hoffläger, darinnen alle seine Konigreich ...Gewonheiten beschrieben werden, Frankfurt 1576; The Prester John of the Indies, 2 vol., ed. by C. F. Beckingham a. G.W.Huntingford, Cambridge 1961; Dokumente zur Geschichte der europäischen Expansion, Bd. 2: Die großen Entdeckungen, hrsg. v. Mathias Meyn u. Eberhard Schmitt, München 1984, 223-227, Nr. 47; Verdadeira informacao sobre a terra do Preste Joao das Indias, 2 Bde, Lissabon 1989 (Kommentar v. J. do Santos Ramalo Cosme).

Lit.: K. Krause: Die Portugiesen in Abessinien. Ein Beitrag zur Entdeckungsgeschichte von Afrika, Dresden 1912; - Francis M. Rogers: The Quest for Eastern Christians, Minneapolis MA 1962; - Richard Pankhurst: Travellers in Ethiopia, London 1965; - Robert Silverberg: The realm of Prester John, Athens/Ohio 1972; - Dietmar Henze: Enzyklopädie der Entdecker und Erforscher der Erde, Bd. 1, Graz 1978, 62-65; - Ulrich Knefelkamp: Die Suche nach dem Reich des Priesterkönigs Johannes, Gelsenkirchen 1986; - Ulrich Knefelkamp: Der portugiesische Franziskaner Francisco Alvares als Missionar im diplomatischen Dienst in Äthiopien (1520-1526), in: Regiones Paeninsulae Balcanicae et proximi Orientis, Festschrift Basilius S. Pandzic, Bamberg 1988, 36-54; - Wilhelm Baum: Die Verwandlungen des Mythos vom Reich des Priesterkönigs Johannes, Klagenfurt 1999; - Wilhelm Baum: Äthiopien und der Westen im Mittelalter, Klagenfurt 2001.

Wilhelm Baum

www.bautz.de/bbkl

Prete Gianni - o Prèsto Janni - pari derivi da zan hoy, cioè mio signore, in quanto gli Etiopi si rivolgevano così al loro

re, come viene spiegato in fondo a questa relazione. Il Prete Gianni era una

figura leggendaria di re e sacerdote, al quale nel Medioevo, specialmente dopo

il sec. XII, si attribuiva un non meno misterioso regno che la fantasia

popolare si raffigurava ricchissimo e potentissimo. Marco Polo![]() collocò

questo regno nello Shansi, regione della Cina. Nei sec. XIV e XV proprio il

desiderio di conoscere questo regno fu stimolo e occasione a numerosi viaggi:

i frati Giordano di Séverac e Giovanni dei Marignolli lo collocarono in

Etiopia, mentre i navigatori portoghesi lo cercarono sulle coste del Mar

Rosso. La critica storica moderna ha sfatato la leggenda riguardo al

personaggio e al suo fantomatico regno.

collocò

questo regno nello Shansi, regione della Cina. Nei sec. XIV e XV proprio il

desiderio di conoscere questo regno fu stimolo e occasione a numerosi viaggi:

i frati Giordano di Séverac e Giovanni dei Marignolli lo collocarono in

Etiopia, mentre i navigatori portoghesi lo cercarono sulle coste del Mar

Rosso. La critica storica moderna ha sfatato la leggenda riguardo al

personaggio e al suo fantomatico regno.

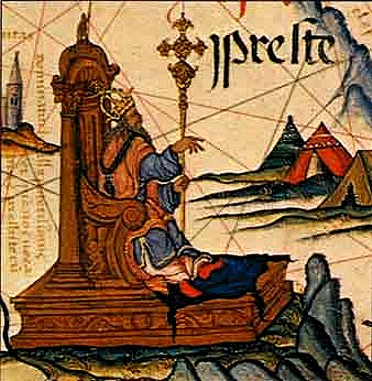

Prete Gianni

Prester John da Hartmann Schedel's Nuremberg Chronicle -1493

Il Prete Gianni rappresenta un personaggio leggendario molto popolare in epoca medievale, tanto che, secondo i poemi del ciclo bretone, il Santo Graal sarebbe stato trasportato proprio nel suo regno. Ludovico Ariosto ne fa uno dei personaggi del suo Orlando furioso con il nome di Senapo, re d'Etiopia, che Astolfo libera da una maledizione divina che lo costringeva a soffrire in eterno la fame. Invece Dante non ne fa cenno.

Lettera del Prete Gianni

La prima notizia che lo riguarda e lo cita giunse in occidente in modo romanzesco nel 1165. L'imperatore bizantino Manuele I Comneno ricevette una strana lettera, da lui poi girata a papa Alessandro III e a Federico Barbarossa. Il mittente delle missive si qualificava come: «Giovanni, Presbitero, grazie all'Onnipotenza di Dio, Re dei Re e Sovrano dei sovrani».

La lettera, in termini eccessivamente ampollosi anche per quei tempi, descriveva il regno di questo re e prete dell'estremo oriente. Si trattava di domini immensi: egli, definendosi «signore delle tre Indie», diceva di vivere in un immenso palazzo fatto di gemme, tenute insieme da oro usato come cemento, e aveva non meno di diecimila invitati a ogni pasto. Sette re, sessantadue duchi e trecentosessantacinque conti gli facevano da camerieri. Tra i suoi sudditi non annoverava solo uomini, ma anche folletti, nani, giganti, ciclopi, centauri, minotauri, esseri con la testa di cane (cinocefali), creature con la faccia sul petto e senza testa (blemmi), esseri con un gigantesco piede solo, che si spostavano strisciando sulla schiena e che si facevano ombra col loro stesso piede (da cui la definizione di sciapodi), etc. Insomma, tutto il campionario di esseri favolosi di cui hanno parlato le letterature e le leggende medioevali. I due imperatori non diedero peso più di tanto a quel fantasioso testo. Il papa, per puro scrupolo (se davvero in Oriente c'era un re cristiano, per giunta prete, rispondere era un dovere), mandò una lettera di esattamente mille parole, in cui lo informava che, una volta giunte notizie più precise, avrebbe inviato il vescovo Filippo da Venezia, nella duplice veste d'ambasciatore e di missionario, per istruire il Prete Gianni nella dottrina cristiana. È da notare che il mitico personaggio si era definito seguace dell'antica eresia nestoriana, condannata al Concilio di Efeso, secondo la quale le due nature di Gesù erano rigidamente separate, e unite solo in modo morale, ma non sostanziale. La corrispondenza si concluse così.

Viaggiatori medievali

Circa venti anni dopo, il vescovo Otto Freising scrisse di aver incontrato in Siria un monaco che gli aveva parlato di un sovrano cristiano, re e sacerdote, che regnava su un grande impero posto oltre l'Armenia e la Persia, ma prima dell'India e della Cina. Passò un altro mezzo secolo. Fra' Giovanni dal Pian del Carpine, che, in veste di ambasciatore del Papa in Estremo Oriente, aveva assistito all'incoronazione del terzo Gran Khan Kuyuk, nella cronaca dei suoi viaggi (Historia Mongolorum) narra di come il successore di Gengis Khan, Ogüdai, era stato sconfitto dai sudditi di un re cristiano, il Prete Gianni, conosciuti come «Quegli Indiani chiamati Saraceni neri, o anche Etiopi».

Marco Polo![]() , nel Milione,

fornisce una versione molto più elaborata della storia. Il Prete Gianni è

descritto come un grande imperatore, signore di un immenso dominio esteso

dalle giungle indiane ai ghiacci dell'estremo nord. I Tartari erano suoi

sudditi, gli pagavano tasse ed erano l'avanguardia delle sue truppe. Questo

fino al giorno in cui non elessero Gengis Khan loro khan. Quest'ultimo, come

riconoscimento della propria indipendenza, chiese in moglie una figlia del

Prete Gianni. Avutone un rifiuto, gli mosse guerra. Una serie di eventi

sensazionali accompagnarono la campagna militare che si chiuse con la vittoria

tartara. Per circa un secolo, nessuno più parlò di tale personaggio.

, nel Milione,

fornisce una versione molto più elaborata della storia. Il Prete Gianni è

descritto come un grande imperatore, signore di un immenso dominio esteso

dalle giungle indiane ai ghiacci dell'estremo nord. I Tartari erano suoi

sudditi, gli pagavano tasse ed erano l'avanguardia delle sue truppe. Questo

fino al giorno in cui non elessero Gengis Khan loro khan. Quest'ultimo, come

riconoscimento della propria indipendenza, chiese in moglie una figlia del

Prete Gianni. Avutone un rifiuto, gli mosse guerra. Una serie di eventi

sensazionali accompagnarono la campagna militare che si chiuse con la vittoria

tartara. Per circa un secolo, nessuno più parlò di tale personaggio.

Scoperte geografiche

Tornò agli onori delle cronache all'improvviso. Sino a quel momento, tutti coloro che avevano parlato del regno del Prete Gianni avevano detto di star riferendo voci. Un viaggiatore inglese, John Mandeville, raccontò invece che vi era stato; nel 1355 fu in cura presso il medico di Liegi Jean de Bourgogne e, al momento di andarsene, gli lasciò il manoscritto delle sue memorie. Il testo vide una diffusione enorme, ma nel 1371, in punto di morte, il medico belga confessò di essersi inventato tutto. I viaggi del gentiluomo inglese inoltre descrivono e accreditano tutte le favole precedenti e ne aggiungono altre. Unico particolare, sembra che lascino pensare a una localizzazione africana anziché asiatica.

Tale tesi

conquistò il re Giovanni II del Portogallo che nel 1489 inviò un'ambasceria

in Egitto, proprio con lo scopo di giungere nel paese del Prete Gianni. I

messi raggiunsero l'Etiopia, dove trovarono davvero dei re cristiani

sottomessi a un imperatore (Negus) che si proclamava discendente di re Davide.

Quest'ultimo mandò a sua volta ambasciatori a Lisbona. I geografi

cominciarono a indicare l'Etiopia come "Regno del Presbitero

Giovanni" e storici come Giuseppe Scaligero![]() ipotizzarono che, un tempo, i domini etiopi giungessero sino alla Cina. Ben

presto, però, ci si rese conto che non era così. Il Prete Gianni è citato

anche su carte geografiche tardo-medievali, come il mappamondo di Martin

Behaim.

ipotizzarono che, un tempo, i domini etiopi giungessero sino alla Cina. Ben

presto, però, ci si rese conto che non era così. Il Prete Gianni è citato

anche su carte geografiche tardo-medievali, come il mappamondo di Martin

Behaim.

Mito o figura storica?

Forse però non si tratta solo di una figura mitologica. Nel 1926, il giornale cattolico americano The Catholic World pubblicò un articolo, firmato John Crowe, in cui si sosteneva che in Asia esiste un Re-sacerdote: il Dalai Lama. Ne consegue che il regno del Prete Gianni sarebbe stato il Tibet. Pur non potendolo escludere, c’è da ricordare che le ricerche più recenti hanno appurato che forse il più vicino alla realtà era proprio Marco Polo. La Chiesa Cristiana Nestoriana (detta anche, impropriamente, assira) ha, ancora oggi, la sua "testa" gerarchica in territori che oggi, politicamente fanno parte di Iraq, Iran e Afghanistan e che, anticamente, erano Persia e il grosso dei fedeli è concentrato oggi in India, ma nel corso del VI e VII secolo espletò un'intensa attività missionaria in Asia Centro-Orientale, in particolare tra le popolazioni turco-mongole, (ma anche in Tibet, Siam e nella stessa Cina). Fra tali missionari, si ricorda la figura del monaco siriano Alopen, che, nell'anno 635, ottenne dall'imperatore cinese T'ai-tsung il permesso di costruire chiese e monasteri e di importare 530 libri religiosi e tradurne in cinese 35.

Anche alcuni sovrani Uiguri (attuale Sinkiang Uighur, Cina occidentale) e Mancesi (Manciuria, Cina nord-orientale) si convertirono a questa fede. Una popolazione tartaro-uigura, l'etnia dei Kara Khitay (vocabolo turco che vuol dire cinesi neri, da cui forse i saraceni neri detti etiopi di Fra' Giovanni dal Pian del Carpine), formò un immenso impero esteso, al momento della massima espansione, dalla Cina settentrionale e dall'Altai al Lago d'Aral, che durò tra X, XI e XII secolo. Si tratta della dinastia e del popolo che gli storici cinesi chiamano "Liao". Il suo più grande condottiero fu il khan Yeliutashi. Sconfisse Arabi, Tartari, Turchi, Cinesi e Russi, e regnò dal 1126 al 1144. Yeliutashi era cristiano nestoriano, come lo erano molti suoi sudditi. Alla sua morte l’impero si divise. L’ultimo della sua dinastia fu Toghrul, di cui Gengis era nominalmente vassallo e che tale rimase fin che non lo sconfisse. Ancora ai tempi di Marco Polo un esponente di questa dinastia regnava sugli Uiguri, vassallo di Kublai Khan. Nel 1292 Fra' Giovanni da Monte Corvino sostenne di averne conosciuto il successore, di nome Giorgio, e di averlo convertito al Cattolicesimo.

Il Prete Gianni nel fumetto

Dopo la scoperta delle Americhe non mancò chi localizzò il Prete Gianni in Florida, e lo collegò a un altro mito, quello della fonte della giovinezza. Questa è anche la versione di Alfredo Castelli, autore del fumetto italiano Martin Mystère, che lo fa vivere dal 1101 al 1344. Egli però ha fatto la sua comparsa anche nei fumetti della Marvel. Si tratta di un personaggio minore, una sorta di strano cavaliere medievale, le cui avventure spaziano dalla corte di re Artù, a quella di Riccardo Cuor di Leone e si intrecciano spesso con quelle di un altro personaggio medievaleggiante della Marvel, Sir Perceval il Cavaliere Nero. Tale "Prete Gianni" (chiamato all'inglese Prester John) possiede un amuleto pressoché onnipotente, ottenuto coniugando tecnologie aliene e magia, il cosiddetto Occhio del male. Tale attrezzo è desiderato da potenti entità, come il dio vichingo del male, della magia e del fuoco Loki e il misterioso demone Dormammu, signore di un universo tenebroso. Ciò perché tale attrezzo è in grado, tra l'altro, anche di fondere tra loro gli universi paralleli. Proprio la ricerca di tale attrezzo è il preludio a uno dei primi e più emozionanti cross-over della Marvel: la saga de "I Difensori vs I Vendicatori" (edizione italiana 1974, a cura dell'editoriale Corno).

Image

of Prester John, enthroned, in a map of East Africa

in Queen Mary's Atlas, Diego Homem, 1558

The legends of Prester John (also Presbyter John), popular in Europe from the 12th through the 17th centuries, told of a Christian patriarch and king said to rule over a Christian nation lost amidst the Muslims and pagans in the Orient. Written accounts of this kingdom are variegated collections of medieval popular fantasy. Reportedly a descendant of one of the Three Magi, Prester John was said to be a generous ruler and a virtuous man, presiding over a realm full of riches and strange creatures, in which the Patriarch of Saint Thomas resided. His kingdom contained such marvels as the Gates of Alexander and the Fountain of Youth, and even bordered the Earthly Paradise. Among his treasures was a mirror through which every province could be seen, the fabled original from which derived the "speculum literature" of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, in which the prince's realms were surveyed and his duties laid out.

At first, Prester John was imagined to be in India; tales of the "Nestorian" Christians' evangelistic success there and of Thomas the Apostle's subcontinental travels as documented in works like the Acts of Thomas probably provided the first seeds of the legend. After the coming of the Mongols to the Western world, accounts placed the king in Central Asia, and eventually Portuguese explorers convinced themselves they had found him in Ethiopia. Prester John's kingdom was the object of a quest, firing the imaginations of generations of adventurers, but remaining out of reach. He was a symbol to European Christians of the Church's universality, transcending culture and geography to encompass all humanity, in a time when ethnic and interreligious tension made such a vision seem distant.

Origin of the legend

The stories of Saint Thomas proselytizing in India, which date back to at least the 3rd century, had obvious influence on the legend's development. Distorted reports of the Assyrian Church of the East's movements in Asia had a hand as well. This church, called "Nestorian" by Europeans who mistook it as adhering to the teachings of Nestorius, gained a wide following in the Eastern nations and engaged the Western imagination as an assemblage both exotic and familiarly Christian. Additionally, a kernel of the tradition may have been drawn from Saint Irenaeus's quotes, recorded by the ecclesiastical historian and bishop Eusebius of Caesarea, on the shadowy early Christian figure John the Presbyter of Syria, supposed in one document to be the author of two of the Epistles of John. The martyr bishop Papias had been Irenaeus' teacher; Papias in turn had received his apostolic tradition from John the Presbyter. Little links this figure to the Prester John legend beyond the name, however.

Whatever its influences, the legend began in earnest in the early 12th century with two reports of visits of an Archbishop of India to Constantinople and of a Patriarch of India to Rome at the time of Pope Callixtus II (1119 – 1124). These visits apparently from the Saint Thomas Christians of India cannot be confirmed, evidence of both being secondhand reports. Later, the German chronicler Otto of Freising reports in his Chronicon of 1145 that the previous year he had met a certain Hugh, bishop of Jabala in Syria, at the court of Pope Eugene III in Viterbo. Hugh was an emissary of Prince Raymond of Antioch seeking Western aid against the Saracens after the Siege of Edessa, and his counsel incited Eugene to call for the Second Crusade. He told Otto, in the presence of the pope, that Prester John, a Nestorian Christian who served in the dual position of priest and king, had regained the city of Ecbatana from the brother monarchs of Medes and Persia, the Samiardi, in a great battle "not many years ago". Afterwards Prester John allegedly set out for Jerusalem to rescue the Holy Land, but the swollen waters of the Tigris compelled him to return to his own country. His fabulous wealth was demonstrated by his emerald scepter; his holiness by his descent from the Three Magi.

Otto's story appears to be a muddled version of real events. In 1141, the Kara-Khitan Khanate under Yelü Dashi defeated the Seljuk Turks near Samarkand. The Seljuks ruled over Persia at the time and were the most powerful force in the Muslim world, and the defeat at Samarkand weakened them substantially. The Kara-Khitan were not Christians, however, and there is no reason to suppose Yelü Dashi was ever called Prester John. However, several vassals of the Kara-Khitan practiced Nestorian Christianity, which may have contributed to the legend. The idea was introduced into the academic mainstream by Lev Gumilev in his popular book about Prester John, "Searches for an Imaginary Kingdom" (1970). Whatever the case may be, the defeat encouraged the Crusaders and inspired a notion of deliverance from the East, and it is possible Otto recorded Hugh's confused report to prevent complacency in the Crusade's European backers; according to his account no help could be expected from a powerful Eastern king.

Letter of Prester John

No more of the tale is recorded until about 1165 when copies of the Letter of Prester John started spreading throughout Europe. An epistolary wonder tale with parallels suggesting its author knew the Romance of Alexander and the above-mentioned Acts of Thomas, the Letter was supposedly written to the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Comnenus (1143 – 1180) by Prester John, descendant of one of the Three Magi and King of India. The many marvels of richness and magic it contained captured the imagination of Europeans, and it was translated into numerous languages, including Hebrew. It circulated in ever more embellished form for centuries in manuscripts, a hundred examples of which still exist. The invention of printing perpetuated the letter's popularity in printed form; it was still current in popular culture during the period of European exploration. Part of the letter's essence was that a lost kingdom of Nestorian Christians still existed in the vastnesses of Central Asia.

The reports were so far believed that Pope Alexander III sent a letter to Prester John via his emissary Philip, his physician, on September 27, 1177. Of Philip, nothing more is recorded, but it is most probable he did not return with word from Prester John. The Letter continued to circulate, accruing more embellishments with each copy. In modern times textual analysis of the letter's variant Hebrew versions have suggested an origin among the Jews of northern Italy or Languedoc: several Italian words remained in the Hebrew texts. At any rate, the Letter’s author was most likely a Westerner, though his or her purpose remains unclear.

Mongol Empire

In 1221 Jacques de Vitry, Bishop of Acre, returned from the disastrous Fifth Crusade with good news: King David of India, the son or grandson of Prester John, had mobilized his armies against the Saracens. He had already conquered Persia, then under the Khwarezmian Empire's control, and was moving on towards Baghdad as well. This descendent of the great king who had defeated the Seljuks in 1141 planned to reconquer and rebuild Jerusalem.

The bishop of Acre was right in the fact that a great King was conquering Persia; however "King David", as it turned out, was no benevolent Nestorian monarch nor even a Christian, but the pagan warlord Genghis Khan. His reign took the story of Prester John in a new direction. The Mongol Empire's rise gave Western Christians the opportunity to visit lands they had never seen before, and they set out in large numbers along the Empire's secure roads. Belief that a lost Nestorian kingdom existed in the east, or that the Crusader states' salvation depended on an alliance with an Eastern monarch, explains the numerous Christian ambassadors and missionaries sent to the Mongols. These include the Franciscan explorers Giovanni da Pian del Carpine in 1245 and William of Rubruck in 1253.

The link between Prester John and Genghis Khan was elaborated upon at this time as the Prester became identified with Genghis' foster father, Toghrul, king of the Keraits, given the Jin title Wang Khan Toghrul. Fairly truthful chroniclers and explorers such as Marco Polo, Crusader-historian Jean de Joinville, and the Franciscan voyager Odoric of Pordenone stripped Prester John of much of his otherworldly veneer, portraying him as a more realistic earthly monarch. Joinville describes Genghis Khan in his chronicle as a "wise man" who unites all the Tartar tribes and leads them to victory against their strongest enemy, Prester John. William of Rubruck says a certain "Vut", lord of the Keraits and brother to the Nestorian King John, was defeated by the Mongols under Genghis. Genghis made off with Vut's daughter and married her to his son, and their union produced Möngke, the Khan at the time William wrote. According to Marco Polo's Travels, the war between the Prester and Genghis started when Genghis, new ruler of the rebellious Tartars, asked for the hand of Prester John's daughter in marriage. Angered that his lowly vassal would make such a request, Prester John denied him in no uncertain terms. In the war that followed, Genghis triumphed and Prester John perished.

The historical figure behind these accounts, Toghrul, was in fact a Nestorian Christian monarch defeated by Genghis. He had fostered the future Khan after the death of his father Yesugei and was one of his early allies, but the two had a falling out. After Toghrul rejected a proposal to wed his son and daughter to Genghis' children, the rift between them grew until war broke out in 1203. Genghis captured Toghrul's daughter Sorghaghtani Beki and married her to his son Tolui; they had several children, including Möngke, Kublai, Hulagu, and Ariq Böke.

The major characteristic of Prester John tales from this period is the kings' portrayal not as an invincible hero, but merely one of many adversaries defeated by the Mongols. But as the Mongol Empire collapsed, Europeans began to shift away from the idea that Prester John had ever really been a Central Asian king. At any rate they had little hope of finding him there, as travel in the region became dangerous without the security the Empire had provided. In works such as The Travels of Sir John Mandeville and Historia Trium Regum by John of Hildesheim, Prester John's domain tends to regain its fantastic aspects and finds itself located not on the steppes of Central Asia, but back in India proper, or some other exotic locale. Wolfram von Eschenbach tied the history of Prester John to the Holy Grail legend in his poem Parzival, in which the Prester is the son of the Grail maiden and the Saracen knight Feirefiz.

Ethiopia

Though Prester John had been considered the ruler of India since the legend's beginnings, "India" was a vague concept to the Europeans. Writers often spoke of the "Three Indias", and lacking any real knowledge of the Indian Ocean, they sometimes considered Ethiopia one of the three. Westerners knew Ethiopia was a powerful Christian nation, but contact had been sporadic since the rise of Islam. Since no Prester John was to be found in Asia, European imagination moved him around the blurry frontiers of "India" until they found an appropriately powerful kingdom for him in Ethiopia.

Marco Polo had discussed Ethiopia as a magnificent Christian land and Orthodox Christians had a legend that the nation would one day rise up and invade Arabia, but they did not place Prester John there. Then in 1306 thirty Ethiopian ambassadors from Emperor Wedem Arad came to Europe, and Prester John was mentioned as the patriarch of their church in a record of their visit. The first clear description of an African Prester John is in the Mirabilia Descripta of Dominican missionary Jordanus, around 1329. In discussing the "Third India", Jordanus records a number of fanciful stories about the land and its king, whom he says Europeans call Prester John. After this point, an African location became increasingly popular; by the time the emperor Lebna Dengel and the Portuguese had established diplomatic contact with each other in 1520, Prester John was the name by which Europeans knew the Emperor of Ethiopia.

The Ethiopians, though, had never called their emperor that. When ambassadors from Emperor Zara Yaqob attended the Council of Florence in 1441, they were confused when council prelates insisted on referring to their monarch as Prester John. They tried to explain that nowhere in Zara Yaqob's list of regnal names did that title occur. "No matter," says Robert Silverberg, author of The Realm of Prester John. "Prester John was what Europe wanted to call the King of Ethiopia, and Prester John is what Europe called him." Some writers who used the title did understand it was not an indigenous honorific; for instance Friar Jordanus seems to use it simply because his readers would have been familiar with it, not because he thought it authentic.

While Ethiopia has been claimed for many years as the origin of the Prester John legend, most modern experts believe the legend was simply adapted to fit that nation in the same fashion it had been projected upon Wang Khan and Central Asia during the 13th century. Modern scholars find nothing about the Prester or his country in the early material that would make Ethiopia a more suitable identification than any place else, and furthermore, specialists in Ethiopian history have effectively demonstrated the story was not widely known there until well after European contact. When the Czech Franciscan Remedius Prutky asked Emperor Iyasu II about this identification in 1751, Prutky states the man was "astonished, and told me that the kings of Abyssinia had never been accustomed to call themselves by this name." In a footnote to this passage, Richard Pankhurst opines that this is apparently the first recorded statement by an Ethiopian monarch about this tale, and they were likely ignorant of the title until Prutky's inquiry.

End of the legend

When 17th century academics like the German orientalist Hiob Ludolf proved that there was no actual native connection between Prester John and the Ethiopian monarchs, the fabled king left the maps for good. But the legend had affected several hundred years of European and world history, directly and indirectly, by encouraging Europe's explorers, missionaries, scholars and treasure hunters.

Literary references

Though the prospect of finding Prester John had long since vanished, the tales continued to inspire through the 20th century. William Shakespeare's 1600 play Much Ado About Nothing contains an early modern reference to the legendary king, and in 1910 British novelist and politician John Buchan used the legend in his sixth book, Prester John, to supplement a plot about a Zulu uprising in South Africa. The book was popular, and exists as an excellent example of the early 20th century adventure novel. Perhaps due to Buchan's work, Prester John appeared in pulp fiction and comics throughout the century. For example, Marvel Comics has featured "Prester John" in issues of Fantastic Four and Thor.

Charles Williams, a prominent member of the 20th century literary group the Inklings, made Prester John a messianic protector of the Holy Grail in his 1930 novel War in Heaven. The Prester and his kingdom also figure prominently in Umberto Eco's 2000 novel Baudolino, in which the titular protagonist enlists his friends to write the Letter of Prester John for his stepfather Frederick Barbarossa, but it is stolen before they can send it out. Eventually Baudolino and company determine to visit the priest's wonderful kingdom which turns out to be everything and nothing like they expected.