Lessico

Avena

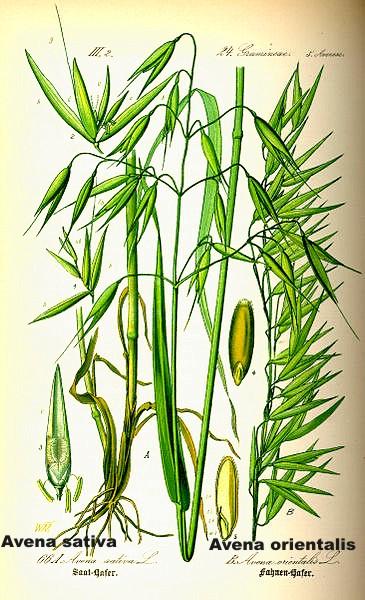

Avena sativa

L’Avena sativa, di cui esiste anche la varietà nuda, ha fiori che spesso si presentano glabri alla base. Invece nell’Avena fatua, che è infestante, i fiori sono sempre barbati alla base. Il frutto dell’Avena sativa è una cariosside oblunga, appuntita, che serve per l'alimentazione del bestiame (biada), in particolare degli equini, in quanto le glumette contengono avenina, stimolante del sistema neuromuscolare. La classificazione risale a Linneo: 1753 per la sativa, 1756 per la varietà nuda.

Avena sativa nuda

Avena comune

L'avena comune (Avena sativa) è una pianta della famiglia delle Poacee (o Graminacee) ed è la specie più nota del genere Avena. L'avena presenta il tipico fusto erbaceo delle graminacee, detto culmo, cavo e sottile e suddiviso in diversi internodi. Le foglie sono sottili e allungate, a nervature parallele, avvolte a guaina intorno al culmo in modo da ricoprire un intero internodo ciascuna. Dai fiori, riuniti a gruppi di 2 o 3 in infiorescenze lasse a spighette, si sviluppano le cariossidi, vale a dire frutti secchi e indeiscenti, ricchi di amido. Le glumette, le brattee che avvolgono le cariossidi, si prolungano in due caratteristiche ariste sottili.

Le varietà utilizzate in agricoltura furono selezionate circa 4500 anni fa a partire da specie selvatiche, da coltivatori europei e mediorientali. L'avena viene generalmente seminata all'inizio della primavera e raccolta in piena o tarda estate; nelle regioni meridionali dell'Europa e del Nord America può essere seminata anche in autunno. La specie più diffusamente coltivata è Avena sativa, mentre Avena fatua, nota con il nome comune di avena folle, è considerata una pianta infestante difficile da eliminare, che cresce in Europa, nel Nord America e in Asia.

Al momento del raccolto i chicchi d'avena consistono di cariossidi (frutti) altamente digeribili avvolte da un tegumento non digeribile. Rispetto ad altri cereali, l'avena integrale produce un alimento ricco di proteine (12%), grassi (7%), fibre (dal 12 al 14%) e carboidrati (circa 64%). Rispetto alle varietà comuni, fino a qualche tempo fa, quelle attualmente coltivate hanno rese più elevate e sono più ricche di proteine e di sostanze energetiche; sono inoltre più resistenti alla ruggine, ai virus e alle aggressioni di insetti. Se consumata sotto forma di cereali ottenuti dai chicchi tostati, l'avena è un'ottima fonte di proteine e di tiamina o vitamina B1.

Avena fatua

Fu

descritta già da Plinio il Vecchio![]() . Essendo molto nutriente,

l'avena integrale è ideale nelle convalescenze e durante l'allattamento.

Possiede una buona percentuale di lisina. Regola la tiroide Rinforza tendini e

ossa. Veniva somministrata ai cavalli per un buono sviluppo dei muscoli. È

utile a chi soffre di insonnia e di disordini dell'appetito. A dosi alte può

dare luogo a cefalea, soprattutto localizzata nella zona della nuca, per

l'elevato contenuto di vitamina B2. Regola il colesterolo. È utile a chi

soffre di emorroidi.

. Essendo molto nutriente,

l'avena integrale è ideale nelle convalescenze e durante l'allattamento.

Possiede una buona percentuale di lisina. Regola la tiroide Rinforza tendini e

ossa. Veniva somministrata ai cavalli per un buono sviluppo dei muscoli. È

utile a chi soffre di insonnia e di disordini dell'appetito. A dosi alte può

dare luogo a cefalea, soprattutto localizzata nella zona della nuca, per

l'elevato contenuto di vitamina B2. Regola il colesterolo. È utile a chi

soffre di emorroidi.

I chicchi di avena vengono destinati all'alimentazione umana o animale; le piante verdi sono spesso messe a fieno, immagazzinate nei silos e utilizzate come foraggio, mentre le piante essiccate costituiscono un ottimo materiale da lettiera per il bestiame. L'avena rappresenta un'importante coltura da rotazione nelle aziende agricole che dispongono di bestiame e di terreno arabile.

L'avena contiene

antiossidanti che impediscono ai cibi grassi di irrancidire; per questa

proprietà, viene generalmente usata come additivo di diversi cibi e nella

produzione delle carte in cui si avvolgono gli alimenti. Uno dei principali

prodotti industriali ottenuti da questo cereale è il furfurolo, una sostanza

chimica derivata dal tegumento della cariosside, utilizzata come solvente in

alcuni processi di raffinazione industriale. Inoltre, l'avena viene impiegata

in distilleria per la produzione del whisky![]() .

.

Avena sativa

The common oat (Avena sativa) is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural, unlike other grains). While oats are suitable for human consumption as oatmeal and rolled oats, one of the most common uses is as livestock feed. Oats make up a large part of the diet of horses and are regularly fed to cattle as well. Oats are also used in some brands of dog and chicken feed.

The wild ancestor of Avena sativa and the closely-related minor crop, A. byzantina, is the hexaploid wild oat A. sterilis. Genetic evidence shows that the ancestral forms of A. sterilis grow in the Fertile Crescent of the Near East. Domesticated oats appear relatively late, and far from the Near East, in Bronze Age Europe. Oats, like rye, are usually considered a secondary crop, i.e. derived from a weed of the primary cereal domesticates wheat and barley. As these cereals spread westwards into cooler, wetter areas, this may have favoured the oat weed component, leading to its eventual domestication.

Oats are grown throughout the temperate zones. They have a lower summer heat requirement and greater tolerance of rain than other cereals like wheat, rye or barley, so are particularly important in areas with cool, wet summers such as Northwest Europe, even being grown successfully in Iceland. Oats are an annual plant, and can be planted either in autumn (for late summer harvest) or in the spring (for early autumn harvest).

Historical attitudes towards oats vary. Oat bread was first manufactured in England, where the first oat bread factory was established in 1899. In Scotland they were, and still are, held in high esteem, as a mainstay of the national diet. A traditional saying in England is that "oats are only fit to be fed to horses and Scotsmen", to which the Scottish riposte is "and England has the finest horses, and Scotland the finest men". Samuel Johnson notoriously defined oats in his Dictionary as "a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people".

Oats have numerous uses in food; most commonly, they are rolled or crushed into oatmeal, or ground into fine oat flour. Oatmeal is chiefly eaten as porridge, but may also be used in a variety of baked goods, such as oatcakes, oatmeal cookies, and oat bread. Oats are also an ingredient in many cold cereals, in particular muesli and granola. Oats may also be consumed raw, and cookies with raw oats are becoming popular. Oats are also occasionally used in Britain for brewing beer. Oatmeal stout is one variety brewed using a percentage of oats for the wort. The more rarely used Oat Malt is produced by the Thomas Fawcett & Sons Maltings and was used in the Maclay Oat Malt Stout before Maclay ceased independent brewing operations.

In Scotland a dish called Sowans was made by soaking the husks from oats for a week so that the fine, floury part of the meal remained as sediment to be strained off, boiled and eaten (Gauldie 1981). A cold, sweet drink made of ground oats and milk is a popular refreshment throughout Latin America. Oats are also widely used there as a thickener in soups, as barley or rice might be used in other countries. Oats are also commonly used as feed for horses, for which purpose they are commonly dehulled and rolled. Cattle are also fed oats, either whole, or ground into a coarse flour using a roller mill, burr mill, or hammer mill. Oat straw is prized by cattle and horse producers as bedding, due to its soft, relatively dust-free, and absorbent nature. The straw can also be used for making corn dollies. Oat extract can also be used to soothe skin conditions, e.g. skin lotions. It is the principal ingredient for the Aveeno line of products.

Avena sativa

Oats are generally considered "healthy", or a health food, being touted commercially as nutritious. The discovery of the healthy cholesterol-lowering properties has led to wider appreciation of oats as human food. Oat bran is the outer casing of the oat. Its consumption is believed to lower LDL ("bad") cholesterol, and possibly to reduce the risk of heart disease. Oats contain more soluble fiber than any other grain, resulting in slower digestion and an extended sensation of fullness. One type of soluble fibre, beta-glucans, has proven to help lower cholesterol. After reports found that oats can help lower cholesterol, an "oat bran craze" swept the U.S. in the late 1980s, peaking in 1989, when potato chips with added oat bran were marketed. The food fad was short-lived and faded by the early 1990s. The popularity of oatmeal and other oat products again increased after the January 1998 decision by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) when it issued its final rule allowing a health claim to be made on the labels of foods containing soluble fiber from whole oats (oat bran, oat flour and rolled oats), noting that 3.00 grams of soluble fiber daily from these foods, in conjunction with a diet low in saturated fat, cholesterol, and fat may reduce the risk of heart disease. In order to qualify for the health claim, the whole oat-containing food must provide at least 0.75 grams of soluble fiber per serving. The soluble fiber in whole oats comprises a class of polysaccharides known as Beta-D-glucan.

Beta-D-glucans, usually referred to as beta-glucans, comprise a class of non-digestible polysaccharides widely found in nature in sources such as grains, barley, yeast, bacteria, algae and mushrooms. In oats, barley and other cereal grains, they are located primarily in the endosperm cell wall. Oat beta-glucan is a soluble fiber. It is a viscous polysaccharide made up of units of the sugar D-glucose. Oat beta-glucan is comprised of mixed-linkage polysaccharides. This means that the bonds between the D-glucose or D-glucopyranosyl units are either beta-1, 3 linkages or beta-1, 4 linkages. This type of beta-glucan is also referred to as a mixed-linkage (1?3), (1?4)-beta-D-glucan. The (1?3)-linkages break up the uniform structure of the beta-D-glucan molecule and make it soluble and flexible. In comparison, the non-digestible polysaccharide cellulose is also a beta-glucan but is non-soluble. The reason that it is non-soluble is that cellulose consists only of (1?4)-beta-D-linkages. The percentages of beta-glucan in the various whole oat products are: oat bran, greater than 5.5% and up to 23.0%; rolled oats, about 4%; whole oat flour about 4%.

Oats after corn (maize) have the highest lipid content of any cereal, e.g., greater than 10 percent for oats and as high as 17 percent for some maize cultivars compared to about 2–3 percent for wheat and most other cereals. The polar lipid content of oats (about 8–17% glycolipid and 10–20% phospholipid or a total of about 33%) is greater than that of other cereals since much of the lipid fraction is contained within the endosperm. Oat is the only cereal containing a globulin or legume-like protein, avenalin, as the major (80%) storage protein. Globulins are characterized by water solubility; because of this property, oats may be turned into milk but not into bread. The more typical cereal proteins such as gluten and zein are prolamines (prolamins). The minor protein of oat is a prolamine: avenin. Oat protein is nearly equivalent in quality to soy protein, which has been shown by the World Health Organization to be equal to meat, milk, and egg protein. The protein content of the hull-less oat kernel (groat) ranges from 12–24%, the highest among cereals.

Coeliac disease, or celiac disease, from Greek "koiliakos", meaning "bowel-related", is a disease often associated with ingestion of wheat, or more specifically a group of proteins labelled prolamines, or more commonly, gluten. Oats lack many of the prolamines found in wheat; however, oats do contain avenin. Avenin is a prolamine that is toxic to the intestinal submucosa and can trigger a reaction in some celiacs. Although oats do contain avenin, there are several studies suggesting that oats can be a part of a gluten free diet if it is pure. The first such study was published in 1995.[6] A follow-up study indicated that it is safe to use oats even in a longer period. Additionally, oats are frequently processed near wheat, barley and other grains such that they become contaminated with other glutens. Because of this, the FAO's Codex Alimentarius Commission officially lists them as a crop containing gluten. Oats from Ireland and Scotland, where less wheat is grown, are less likely to be contaminated in this way. Oats are part of a gluten free diet in, for example, Finland and Sweden. In both of these countries there are "pure oat" products on the market.

Oats are sown in the spring or early summer, as soon as the soil can be worked. An early start is crucial to good yields as oats will go dormant during the summer heat. Oats are cold-tolerant and will be unaffected by late frosts or snow. Typically about 125 to 175 kg/hectare (between 2.75 and 3.25 bushels per acre) are sown, either broadcast, drilled, or planted using an airseeder. Lower rates are used when underseeding with a legume. Somewhat higher rates can be used on the best soils, or where there are problems with weeds. Excessive sowing rates will lead to problems with lodging and may reduce yields. Winter oats may be grown as an off-season groundcover and plowed under in the spring as a green fertilizer.

Oats remove substantial amounts of nitrogen from the soil. They also remove phosphorus in the form of P2O5 at the rate of 0.25 pound per bushel per acre (1 bushel = 38 pounds at 12% moisture)[citation needed]; Phosphate is thus applied at a rate of 30 to 40 kg/ha, or 30 to 40 lb/ac. Oats remove potash (K2O) at a rate of 0.19 pound per bushel per acre, which causes it to use 15–30 kg/ha, or 13–27 lb/ac. Usually 50–100 kg/ha (45–90 pounds per acre) of nitrogen in the form of urea or anhydrous ammonia is sufficient, as oats uses about 1 pound per bushel per acre. A sufficient amount of nitrogen is particularly important for plant height and hence straw quality and yield. When the prior-year crop was a legume, or where ample manure is applied, nitrogen rates can be reduced somewhat.

The vigorous growth habit of oats will tend to choke out most weeds. A few tall broadleaf weeds, such as ragweed, goosegrass, wild mustard and buttonweed (velvetleaf), can occasionally be a problem as they complicate harvest and reduce yields. These can be controlled with a modest application of a broadleaf herbicide such as 2,4-D while the weeds are still small. Oats are relatively free from diseases and pests, with the exception being leaf diseases, such as leaf rust and stem rust. A few Lepidoptera caterpillars feed on the plants—e.g. Rustic Shoulder-knot and Setaceous Hebrew Character—but these rarely become a major pest. See also List of oats diseases.

Modern harvest technique is a matter of available equipment, local tradition, and priorities. Best yields are attained by swathing, cutting the plants at about 10 cm (4 inches) above ground and putting them into windrows with the grain all oriented the same way, when the kernels have reached 35% moisture, or when the greenest kernels are just turning cream-color. The windrows are left to dry in the sun for several days before being combined using a pickup header. Then the straw is baled. Oats can also be left standing until completely ripe and then combined with a grain head. This will lead to greater field losses as the grain falls from the heads and to harvesting losses as the grain is threshed out by the reel. Without a draper head, there will also be somewhat more damage to the straw since it will not be properly oriented as it enters the throat of the combine. Overall yield loss is 10–15% compared to proper swathing. Historical harvest methods involved cutting with a scythe or sickle, and threshing under the feet of cattle. Late 19th and early 20th century harvesting was performed using a binder. Oats were gathered into shocks and then collected and run through a stationary threshing machine.

After it is combined, the oats are transported to the farm-yard using a grain truck, semi, or road train, where it is augered or conveyed into a bin for storage. Sometimes, when there is not enough bin-space, it is augered into portable grain rings, or piled on the ground. Oats can be safely stored at 12% moisture; at higher moisture levels, it must be aereated, or dried.

Oats processing is a relatively simple process. Upon delivery to the milling plant, chaff, rocks, other grains, and other foreign material are removed from the oats. Separation of the outer hull from the inner oat groat is effected by means of centrifugal acceleration. Oats are fed by gravity onto the center of a horizontally spinning stone, which accelerates them towards an outer ring. Groat and hull are separated on impact with this ring. The lighter oat hulls are then aspirated away while the denser oat groats are taken to the next step of processing. Oat hulls can be used as feed, processed further into insoluble oat fiber, or used as a biomass fuel. The unsized oat groats will then pass through a heat and moisture treatment to balance moisture, but mainly to stabilize the groat. Oat groats are high in fat (lipids) and once exposed from their protective hull, enzymatic (lipase) activity begins to break down the fat into free fatty acids, ultimately causing an off flavor or rancidity. Oats will begin to show signs of enzymatic rancidity within 4 days of being dehulled and not stabilized. This process is primarily done in food grade plants, not in feed grade plants. An oat groat is not considered a raw oat groat if it has gone through this process: the heat has disrupted the germ, and the oat groat will not sprout.

Many whole oat groats are broken during the dehulling process, leaving the following types of groats to be sized and separated for further processing: Whole Oat Groats, Coarse Steel Cut Groats, Steel Cut Groats and Fine Steel Cut Groats. Groats are sized and separated using screens, shakers and indent screens. After the whole oat groats are separated, the remaining broken groats get sized again into the 3 groups (Coarse, Regular, Fine) and then stored. The term steel cut is referred to all sized or cut groats. When there are not enough broken to size for further processing, then whole oat groats get sent to a cutting unit with steel blades that will evenly cut the groats into the three sizes as discussed earlier.

Three methods are used to make the finished product. Flaking - This process uses two large smooth or corrugated rolls spinning at the same speed in opposite directions at a controlled distance. Oat flakes, also known as rolled oats, have many different sizes, thicknesses and other characteristics depending on the size of oat groat passed between the rolls. Typically the three sizes of steel cut oats are used to make Instant, Baby and Quick rolled oats, whereas whole oat groats are used to make Regular, Medium and Thick Rolled Oats. Oat flakes range from a thickness of 0.36 mm to 1.00 mm. Oat bran milling - This process takes the oat groats through several roll stands that flatten and separate the bran from the flour (endosperm). The two separate products (flour and bran) get sifted through a gyrating sifter screen to further separate them. The final products are oat bran and debranned oat flour. Whole flour milling - This process takes oat groats straight to a grinding unit (stone or hammer mill) and then over sifter screens to separate the coarse flour and final whole oat flour. The coarser flour gets sent back to the grinding unit until it's ground fine enough to be whole oat flour. This method is used very much in India.

Avena sativa

L’avoine cultivée est une plante annuelle appartenant au genre Avena de la famille des Poacées (graminées), et cultivée comme céréale ou comme fourrage. Elle fait partie des céréales à paille et est utilisée principalement dans l’alimentation animale (notamment des équidés). Nom scientifique :Avena sativa L., famille des Poacées, sous-famille des Pooideae, tribu des Aveneae. Le genre Avena comprend outre l’avoine cultivée, de nombreuses espèces, dont notamment Avena fatua, la folle avoine, adventice des grandes cultures. Parmi les céréales à paille, l’avoine se caractérise par son inflorescence en panicule lâche qui regroupe des épillets de trois fleurs. Le grain est un caryopse velu entouré de glumelles non adhérentes mais qui restent fermées.

Alimentation animale: l’avoine en grains était autrefois très utilisée pour l’alimentation des chevaux, à cause de son pouvoir excitant, qui stimule les animaux de trait. Sa valeur énergétique est cependant bien moindre que celle du blé ou de l’orge. Comme fourrage, on la cultive souvent en mélange avec une légumineuse (comme la vesce),ce qui améliore sa teneur en protéines.

Alimentation humaine: flocons d’avoine, porridge, préparation de boissons, biscuits. L'avoine a été consommée par l'homme depuis des milliers d'années. L'interêt pour l'avoine comme aliment bénéfique pour la santé s'est accru depuis les années 1990. En effet, de nombreuses études ont démontré qu'une fibre particulière de l'avoine - le bêta-glucane - a des propriétés régulatrices sur la glycémie et également sur le taux de cholestérol sanguin. De plus les protéines de l'avoine, riches en tryptophane, participent à la production de sérotonine et mélatonine chez l'humain. Les lipides possèdent un taux important de galactolipides, qui pourraient avoir un effet bénéfique sur notre système nerveux. Enfin, l'avoine contient de nombreux anti-oxydants comme les avénanthramides, les tocophérols et les tocotriénols (Bryngelsson et al, 2002).