Lessico

Bernabé Cobo

Simbolo dell'Ordine dei Gesuiti

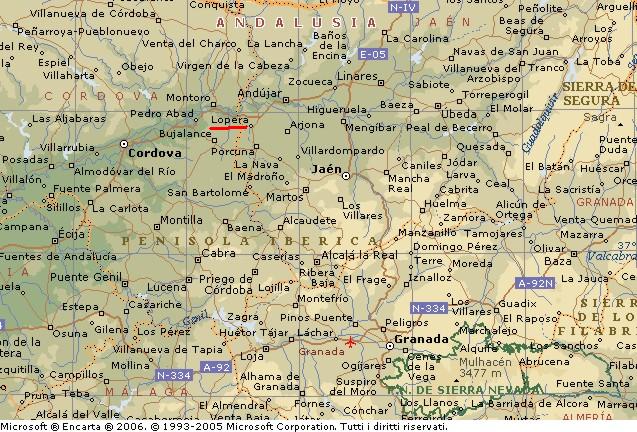

Bernabé Cobo (Lopera, novembre 1580 – Lima, 9 ottobre 1657) è stato un gesuita, naturalista e scrittore spagnolo. La data di nascita di Bernabé Cobo non è stata tramandata, ma sappiamo quella del suo battesimo, che avvenne il 26 novembre del 1580, secondo gli atti ritrovati in Lopera dallo storico A. Vasquez de la Torre. Era il quinto dei sei figli avuti da Juan Cobo e Catalina de Peralta, una famiglia della nobiltà minore di Jaén, che si sostentava grazie a vaste proprietà di uliveti.

Il giovane Bernabé crebbe nella tenuta di famiglia, dedito soprattutto a occupazioni campestri che avrebbero lasciato una traccia indelebile nella sua personalità. La sua educazione letteraria fu elementare, consentendogli soltanto di apprendere a leggere e scrivere.

Da buon "hidalgo" (nobile di seconda categoria) non apprese alcun mestiere e fu giocoforza, per lui, cercare nell'avventura lo scopo della vita. Credette di trovarla nelle Americhe che, allora, richiamavano molti giovani, come lui desiderosi di conquistare con le armi una vita degna di essere vissuta.

In America Centrale

Nel 1596, ammaliato dai racconti e dalle promesse di

Antonio de Berrio, si imbarcò alla volta dell'isola di Trinidad assieme ad

altri duemila sognatori, come lui certi di acquisire, in breve, fama e

ricchezze. Il risveglio da tante illusioni fu quanto mai acerbo. L'isola non

era in grado di nutrire un così grande numero di persone e fu necessario

evacuarne una parte verso le colonie sull'Orinoco.

Il trasferimento non avvenne però tranquillamente, perché una buona metà

dei transfughi venne intercettata dagli indigeni, i temibili Caribe, e incontrò

la morte con eccezione delle donne che vennero ridotte in schiavitù. Cobo,

per sua fortuna non era della partita e aveva veleggiato verso l'isola

Hispaniola dove sarebbe rimasto per un anno.

Per sopravvivere il giovane avventuriero partecipò a numerose escursioni sulle navi che percorrevano i Caraibi, trasferendosi poi a Panama sui bordi del Pacifico. In uno di questi viaggi avvenne l'incontro destinato a cambiare la sua vita. Il Generale dei Gesuiti, Claudio Acquaviva, aveva inviato un suo incaricato, Esteban Páez, a visitare il Perù e questi, viaggiando con Cobo, strinse una profonda amicizia con il giovane. Colpito dalle doti che il suo carattere lasciava intravedere, si offrì di iscriverlo nel Collegio dei Gesuiti di Lima per approfondire la sua educazione. Cobo accettò con entusiasmo e nel 1599 iniziò a frequentare i corsi del prestigioso Collegio assieme ai figli dei più autorevoli personaggi della colonia peruviana.

In Perù

Inizialmente Cobo, nel Collegio di San Martn di Lima, attese soltanto a acquisire quelle nozioni che mancavano alla sua educazione elementare, ma la vita pia dell'ambiente risvegliò in lui una vocazione che dimorava latente nel suo animo e che lo convinse ad abbracciare la vita religiosa.

Al termine dei primi due anni chiese pertanto di restare e di entrare nell'Ordine dei Gesuiti. Accettato dai suoi superiori, proseguì gli studi prescritti e il 18 ottobre del 1603 pronunciò i primi voti religiosi. Doveva però completare i suoi studi, cosa che compì con ardore, frequentando negli anni successivi i corsi di "Humanidades", di Arte e di Filosofia.

Nel 1609 venne destinato al Cuzco dove sarebbe rimasto per quattro anni. Durante la permanenza nell'antica capitale degli Inca si recò anche, nel 1610, a Tiahuanaco e a La Paz. Pur esercitando attivamente la sua missione religiosa, approfittò della residenza sull'altipiano andino per apprendere gli idiomi locali e si fece interprete sia del quechua, sia dell'aymará.

Al Cuzco si legò in amicizia con Alonso Topa Atau, un nipote dell'antico sovrano Huayna Capac, e per il suo tramite ebbe accesso alle tradizioni incaiche ancora gelosamente conservate. Intanto osservava e catalogava tutte le specie animali e vegetali del paese.

Dopo una parentesi in Lima, in cui completò i suoi ultimi studi ecclesiastici, ritornò sull'altipiano e precisamente a Juli sul Titicaca. Visitò Potosì, Oruro e Chucuito e percorse tutto il Collao, sempre annotando ogni particolarità che gli sembrasse degna di nota. Nel 1618 si trasferì sulla costa, sistemandosi ad Arequipa per oltre tre anni. Non gli sfuggirono le curiosità del luogo e compì delle mirate escursioni a Nazca, Ica e Pisco, sedi di antiche civiltà precedenti quella degli Inca.

Aveva intanto concepito il vasto disegno di scrivere una Storia del Nuovo Mondo dando risalto a tutti i suoi molteplici aspetti, storici anzitutto, ma anche e soprattutto evidenziandone le particolarità naturali, con particolare riguardo al mondo vegetale e animale.

Dopo un ritorno sull'altipiano chiese pertanto di essere trasferito in Messico per studiare quel paese remoto di cui aveva solo delle conoscenze teoriche. Il padre Muzio Vitelleschi, il nuovo generale dell'Ordine, aveva delle perplessità al proposito, ma accondiscese infine al trasferimento e Bernabé Cobo poté abbandonare il Perù nel 1629.

In Messico

La permanenza in Messico e nelle terre limitrofe sarebbe durata ben tredici anni, fino al 1643 e sarebbe stata consacrata alle ricerche botaniche e zoologiche, inframezzate da investigazioni storiche di tutto rilievo. Il Nicaragua e il Guatemala non sfuggirono alle mire del solerte ricercatore che, trasferendosi da una sede del suo Ordine all'altra, ebbe modo di visitare entrambi i paesi rimanendo per ben sette anni in Guatemala. Le osservazioni che ne riportò faranno della sua opera quanto di più approfondito venne prodotto, in quel secolo, sulle materie specifiche dei suoi studi.

Bernabé Cobo già nel 1633 riteneva ultimate le sue ricerche nei territori messicani, ma avrebbe dovuto attendere ancora molti anni prima di avere l'autorizzazione di ritornare in Perù che ormai riteneva la sua patria di adozione.

Ultimi anni

Nel 1643 poté finalmente ritornare a Lima. Aveva ormai 63 anni, ma la sua opera non era ancora finita. Dal Colegio de San Pablo de Lima, sua ultima residenza, continuò, con una lena infaticabile, a perfezionare e ordinare la raccolta delle innumerevoli nozioni che aveva accumulato per tutto il corso della sua vita.

Non smise tuttavia di praticare delle osservazioni dirette e in quegli anni, per esempio, notò la caratteristica della corrente fredda dell'Oceano Pacifico che sarebbe stata in seguito conosciuta come Corrente di Humboldt.

Cobo morì infine, in Lima, il 9 ottobre del 1657.

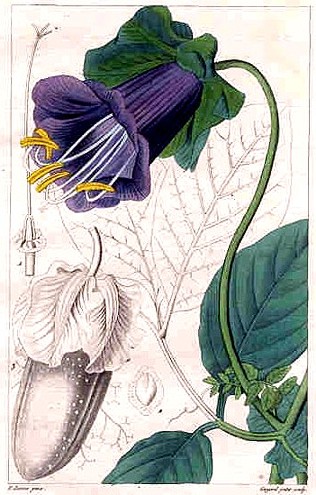

Aveva settantasette anni ed era nelle Indie da sessantuno. Di questi,

quarantotto li aveva passati in Perù. Il botanico spagnolo Antonio José

Cavanilles (1745-1809) diede il nome di Cobaea a un genere di piante

del Messico appartenenti alle Polemoniaceae, essendo la Cobaea

scandens![]() la più rappresentativa.

la più rappresentativa.

Le opere

L'opera fondamentale di Cobo è intitolata Historia del Nuevo Mundo. Si compone di tre parti.

La prima racchiude 14 libri che trattano della natura e qualità del territorio con tutte le cose che vi si trovano.

La seconda consta di 15 libri dedicati alla storia del Perù.

La terza, anch'essa di 14 libri, ha per oggetto la storia del Messico e dei territori limitrofi, nonché la descrizione delle isole di ambo gli oceani fino alle Filippine e alle Molucche.

Purtroppo solo la prima

parte ci è pervenuta, unitamente a tre libri sulla fondazione di Lima che

originariamente dovevano far parte dell'opera generale.

La parte scientifica di questi scritti è soprattutto notevole perché tutte

le notizie e le osservazioni che vi sono riportate sono frutto di

investigazioni dirette da parte del suo autore. La massa di dati che sono

presenti in queste pagine la fanno somigliare a una vera e propria

enciclopedia in cui tutte le proprietà geografiche, minerali, vegetali e

animali sono esaminate.

La parte storica era basata, per quanto riguarda il Messico, su una relazione poco conosciuta di un capitano spagnolo, Bernardino Vásquez de Tapia. Per quanto riguarda il Perù, la traccia di base era la relazione di Pedro Pizarro, ma Cobo aveva effettuato ricerche approfondite anche presso gli archivi ecclesiastici dell'epoca, assimilando notizie contenute in documenti oggi andati perduti. Notevole è sopratutto la parte della relazione sui ceque del Cuzco, già esplicitata da Cristóbal de Molina.

Historia del Nuevo Mundo in Bibl. Aut. Esp. Tomi XCI-XCII Madrid 1956

Fundacion de Lima in Bibl. Aut. Esp. Tomo XCII Madrid 1956

Bernabé Cobo (born at Lopera in Spain, 1580; died at Lima, Peru, 9 October 1657) was a Spanish Jesuit missionary and writer. He played a part in the early history of quinine by his description of cinchona bark; he brought some to Europe on a visit in 1632.

He was a thorough student of nature and man in

Spanish America. His long residence (61 years), his position as a priest and,

several times, as a missionary, gave him unusual opportunities for obtaining

reliable information. The Spanish botanist Antonio José Cavanilles

(1745-1809) gave the name of Cobaea to a genus of plants belonging to

the Polemoniaceae of Mexico, Cobaea

scandens![]() being its most striking

representative.

being its most striking

representative.

He went to America in 1596, visiting the Antilles and Venezuela and landing at Lima in 1599. Entering the Society of Jesus, 14 October, 1601, he was sent by his superiors in 1615 to the mission of Juli, where, and at Potosí, Cochabamba, Oruro, and La Paz, he laboured until 1618. He was rector of the college of Arequipa from 1618 until 1621, afterwards at Pisco, and finally at Callao in the same capacity, as late as 1630. He was then sent to Mexico, and remained there until 1650, when he returned to Peru.

He wrote two works, one of which is incomplete. It is also stated that he wrote a work on botany in ten volumes, which, it seems, is lost.

Of his main work, to which biographers give the title Historia general de las Indias, and which he finished in 1653, only the first half is known and has appeared in print (four volumes, at Seville, 1890 and years succeeding). The remainder, in which he treats, or claims to have treated, of every geographical and political subdivision in detail, has either never been finished, or is lost.

His other book appeared in print in 1882, and forms part of the "History of the New World" mentioned, but he made a separate manuscript of its in 1639, and so it became published as "Historia de la fundación de Lima", a few years before the publication of the principal manuscripts.

The "History of the New World" may, in American literature, be compared with one work only, the "General and Natural history of the Indies" by Oviedo. On the animals and plants of the continent, it is more complete than Nieremberg, Hernandez, and Monardes. In regard to the pre-Columbian past and vestiges, Cobo is, for the South American west coast, a source of primary importance, for close observations of customs and manners, and generally accurate descriptions of the principal ruins of South America.

History of the Inca Empire

An

Account of the Indians' Customs and Their Origin,

Together with a Treatise on Inca Legends, History, and Social Institutions

By Bernabé Cobo

Translated and edited by Roland Hamilton – 1979

from the holograph manuscript in the Biblioteca Capitular y Colombina de

Sevilla

Foreword by John Howland Rowe

Introduction

Father Cobo and His Historia

Bernabé Cobo (1580-1657) became one of the New World's outstanding historians. Born in southern Spain, he spent a year on Hispaniola before continuing on to Peru in 1599. He was to remain in Peru for the rest of his life, except for a trip to New Spain between 1629 and 1642. Cobo was educated as a Jesuit and did extensive missionary work with the Peruvian Indians at intervals from 1609 through 1629. During his sojourn in New Spain and thereafter in Peru, he spent much of his time in the capital cities of Mexico and Lima doing research in archives and libraries for his monumental Historia del Nuevo Mundo, which he finally completed in 1653.

In the prologue to the Historia, Father Cobo explains that his work contains forty-three books divided into three parts; the first part deals with pre-Columbian America, the second with the discovery and conquest of the West Indies and South America, and the third with New Spain. Unfortunately, most of the Historia has been lost; what remains is only the first part, composed of fourteen books, plus three books from the second part concerning the foundation of Lima. The loss of such a large portion of Cobo's Historia is not as regrettable as it may seem because, for contemporary scholars, the account of pre-Columbian Peru is his most important piece of scholarship. He collected a vast amount of material in Peru. This includes the judicious use of the best written sources on the Incas, which Cobo tells us he confirmed through interviews with the descendants of the royal Inca lineage in Cuzco around 1610. Cobo also took careful note of the customs of the plebeian Indians with whom he did his missionary work. This mass was then organized into the most comprehensive and lucid study of its kind. As the eminent Peruvianist John H. Rowe so aptly put it, Cobo's account "is so clear in its phrasing and scientific in its approach that it is pleasant as well as profitable to work with."

The manuscripts of the Historia found their way to Seville, where they remained unnoticed until around 1790, when Juan Bautista Muñoz had copies made for his collection in Madrid. Muñoz's research assistants used two separate manuscripts; one was a large volume containing the ten books from the first part which deal with natural history; the other had the three books on the foundation of Lima. Today the holograph manuscripts for these two volumes are housed in the Biblioteca Universitaria de Sevilla, identified respectively as MSS. 331-2 and MSS. 332-33.

There is a third manuscript including Books 11-14 of the first part; this volume, dealing mainly with pre-Columbian Peru, is located in the Biblioteca Capitular y Colombina de Sevilla; for the sake of brevity, I will refer to it as the Colombina-Cobo MS. It does not bear the author's signature, and it has never been adequately described. The first sign of it came in 1892-1893, when the contents were published by Marcos Jiménez de la Espada, but he made no reference to the manuscript. This was done by Philip A. Means: "The original manuscript, holograph, is in the Muñoz collection in the Royal Academy of History in Madrid." Although Means is a very trustworthy scholar, in this case he made the mistake of using González de la Rosa (see note 1) instead of inspecting the primary sources in Spain. I have personally studied the manuscripts for Cobo's works in the Muñoz collection in Madrid. These are only the copies made around 1790, and they are in the Biblioteca del Palacio Real. Moreover, this collection does not even include a copy of the Colombina-Cobo MS.

The only scholar to identify the Colombina-Cobo MS. Was R. Vargas Ugarte; under the heading "Biblioteca Colombina--Sevilla," he states as follows: "416.-MSS. 83-3-36. 1 vol. en 4.0 encuad. en pergamino, 363 pág. n. Al dorso: Historia del Nuevo Mundo. 2 p.p. 1 Historia del Nuevo Mundo, la. Parte. Libro Undécimo. Cap. 1 Que la América estaba poco poblada y por qué causas. Comprende hasta el Libro Decimocuarto, inclusive. Escrito todo de una misma mano. Origl. Se trata, como el lector habrá advertido, de la obra del P. Bernabé Cobo..." The only error here is the call number. When I visited the Biblioteca Colombina in 1974, the call number was 83-4-24. It should also be noted that this text is done in a clear and careful style of handwriting which makes it easy to work with.

Later scholars who have used Vargas Ugarte have either been noncommittal or have not accepted his identification of the Colombina-Cobo MS. as the original. Porras Barrenechea does not say whether the Colombina- Cobo MS. is original or not, and Francisco Mateos indicates that the originals are missing. In order to remove all doubts about the matter, I have made a comparison of the three surviving letters signed by Cobo and the Colombina-Cobo MS. All of the letters were written in New Spain. The first is dated 7 de Março de 1630 in La Puebla; the second, 21 de Junio de 1633 in Mexico; both of these letters, reports of Cobo's trip through New Spain to members of the Jesuit Society in Peru, are now in the Biblioteca Nacional de Lima. The third letter, dated in 1639, was written in an effort to get the Historia published in Seville; it is in the Biblioteca Universitaria de Sevilla. I have studied the entire text of the Colombina-Cobo MS. as well as the known handwriting and signatures of Cobo as found in the aforementioned letters. I have paid particular attention to the proportional size, spacing, and slant of the letters as well as the use of upper- and lower-case letters and the lack of abbreviations. There is no question that the Colombina-Cobo MS. is the original holograph.

Now that the manuscripts have been identified, it must be pointed out that none of the originals were used for the publication of Cobo's works. The botanist D. Antonio Josef Cavanilles did the first publication of parts of the Historia. He used the Muñoz copies for an article that came out in 1804. The scientific accuracy of Cobo's descriptions of New World flora was illustrated with extensive quotations. As a botanist, Cobo was far ahead of his time, but even by the latest scientific standards of the early nineteenth century, his practical approach, with special emphasis on medicinal plants, was more valuable for ethnobotany than for natural science.

Next, M. González de la Rosa published the Historia de la Fundación de Lima in 1882, using a copy found in the Biblioteca Colombina. It is unfortunate that he did not find the original, also in Seville. This work remains an important source of information on early colonial Lima because many of the documents that were used have now disappeared and Cobo is an original source for events in Lima during the first half of the seventeenth century.

Finally, between the years 1890 and 1893, Marcos Jiménez de la Espada published all fourteen books of the first part of the Historia. Unfortunately Jiménez de la Espada died before finishing the introduction, and he never told which manuscripts he used for this edition. However, since he was working in Madrid, he probably used the Muñoz copies for Books 1-10, and, although it has been assumed that he used the Colombina-Cobo MS. for Books 11-14, I have found evidence that he had a copy that now seems to have disappeared with the notes for the introduction. The fact that a copy was made is borne out by a number of emendations and omissions. For example, the Colombina-Cobo MS., f. 66, v., reads "vilcas," but the printed editions read "Vilgas" [Vilcas] (BAE, 92: 53); the Colombina-Cobo MS., f. 117, v., reads "Collatupa," the printed editions have "CoyaTupa," and note 17 says "Probablemente Colla-Tupa o Tupac" (p. 90). The Colombino-Cobo MS., f. 134, r., reads "unbuhio"; the printed editions have "bujio" [buhio] (p. 102). Furthermore, the Colombina-Cobo MS., f. 49, r., reads "y de los animales peregrinos, y estraños que vemos en algunas islas, como no quedo casta en otras partes?" This whole passage was omitted (p. 40). Other examples of omissions are found in the following places: Colombina-Cobo MS., f. 50, v. (p. 4r); f. 76, r. (p. 59); f. 177, r. (p. 134). The list could be extended, but this is sufficient; no doubt these emendations and omissions were based on the shortcomings of a copy made for Jiménez de la Espada.

In fine, the manuscripts of the Historia, all located in Seville, are in excellent condition. Nevertheless, all published editions are based on imperfect copies. Therefore, new editions, based on the holograph MSS., are urgently needed, especially for the account of pre-Columbian Peru contained in the Colombina-Cobo MS.

http://www.utexas.edu

Inca Religion and Customs

By

Bernabé Cobo

Translated and edited by Roland Hamilton - 1990

foreword by John Howland Rowe

Introduction

Father Cobo and the Incas

Those interested in an accurate understanding of Inca culture must consult the sources, Spanish chronicles written in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Although the Incas left no written records before the conquest, the Spanish chronicles are based on extensive interviews with Inca witnesses and on personal contact with those subjugated by the Incas. A surprisingly large number of these chronicles have survived and are used by all researchers in the field. Many of the documents contain vague and misleading passages which create great difficulties for the reader. One chronicle, however, stands out for its clarity and accuracy. I refer to the works of Father Bernabé Cobo. Completing his research in the first half of the seventeenth century, he produced what has become recognized as one of the most respected sources on the Incas.

In this introduction, I will give some of the highlights of Father Cobo's life, especially that part which relates to his research on the Incas. Then I will discuss the procedure I used to identify the original manuscript of Cobo's works on the Incas and give a resume of this manuscript. I will pay special attention to the section on Inca religion and customs contained in the present translation. Finally, I will comment on Father Cobo's scholarship and on his place among Inca sources.

Father Bernabé Cobo was born in Southern Spain, in the little town of Lopera, in 1580. Evidently he attended elementary school there. In 1595, he traveled to the large city of Seville, at the time a rnajor port of call for ships going to and from America. Young Bernabé must have come to pray at the cathedral, the most prominent building in the city, before embarking on his journey to the New World. Little did he know that after his death his writings on the Incas would be deposited in the library of this same cathedral.

On his way to Peru, Cobo stopped for over a year in the West Indies. Continuing on through Panama, he reached Lima in 1599. The colonial town of Los Reyes, Lima, was a cultural center that boasted the best schools in Spanish America. Here young Bernabé received his secondary education before continuing on to advanced studies with the Jesuit Order.

Father Cobo traveled the Inca roads from Lima to Cuzco in the year 1609. Later, on several different trips, he walked on across most of central and southern Peru. He carefully examined the Inca monuments in Cuzco and also conducted interviews with the descendants of the Incas.

Cobo visited the Lake Titicaca area at least twice, first in 1610 and again in 1615. He did missionary work here, getting to know the people and their languages, Quichua and Aymara. He also visited the ruins of Copacabana and Tiahuanaco.

During subsequent years, Father Cobo served as a Latin teacher in Arequipa and probably became director of a school in the coastal town of Pisco. After 1620, he spent most of his time in Lima, except for an extended trip to Mexico which lasted from 1629 to 1642. Devoting more and more time to his historical writings, he finally finished the Historia del Nuevo Mundo in 1653. He died in Lima in 1657.

Father Cobo explains in the prologue to his Historia that it contained forty-three books divided into three parts. The first deals with the natural history of the New World and the history and customs of the Incas; the second with the discovery and "pacification," as Cobo put it, of the West Indies and Peru, and with colonial institutions; the third deals mainly with New Spain. All that remains to us today is the first part, composed of fourteen books, and three books of the second part which tell of the foundation of Lima.

The manuscript for the section on the Incas, Books 11 through 14 of the first part, resides in the library of the cathedral of Seville, known as the Biblioteca Capitular Colombina. Until 1974, when I visited this library, the manuscript was considered to be a copy of a lost original. However, I wanted to identify Cobo's original writings for myself. Consequently I obtained a microfilm copy of the Colombina manuscript from the director. Next I went to the library of the University of Seville which houses the manuscript for Books 1 through 10, including the prologue, signed by Cobo. This manuscript is uniform in page size and binding with the Colombina manuscript; it is also clear that the two volumes were written in identical handwriting. Thus the prologue applies equally to both Volumes. However, in order to make a positive identification of Cobo's handwriting, I needed another point of comparison. I knew there were letters written by Cobo from Mexico to Lima in 1630 and 1633. So the following year, I headed for Lima to inspect the originals held in the National Library. Careful comparison of the handwriting revealed that the manuscript at the Colombina Library in the cathedral was not a copy, but the original, executed in Cobo's own handwriting.

On the advice of the eminent Andean scholar Professor John H. Rowe, I embarked on a project to translate the manuscript on the Incas. The first fruits of this labor resulted in the History of the Inca Empire, published in 1979 by the University of Texas Press. This is the only publication to date based on Cobo's original MS. This work comprised Books 11 and 12 of the original. Dealing with the physical features and customs of the Indians in general, it gives a detailed account of the origin and history of the Incas. The present translation of Books 13 and 14 of the original discusses Inca religion extensively and covers a wide variety of customs. All other books of Cobo's works published to date were based on imperfect copies of Cobo's originals. For more details, see my introductory materials for the History of the Inca Empire.

Book I of the present translation (Book 13 of the original) contains thirty-eight chapters on Inca religion. In it Father Cobo relates some fascinating origin myths, gives a careful explanation of many deities, and describes the major shrines in detail. He also tells about numerous rites and sacrifices, as well as the role of the priests, sorcerers, and doctors in Inca society.

Book II of this translation (Book 14 of the original)

contains nineteen chapters on Inca customs. This book documents many topics of

everyday life, such as clothing, weaving, building, food, drink, farming,

marriage, and others.

Father Cobo's originality is that of any competent historian: the judicious

use of primary sources in fashioning an overall view or thesis about a

historical situation. His sources included interviews in Cuzco with

descendants of the Incas, careful observation of the customs of the Indian

peasants of the sierra, and the best written accounts by other chroniclers,

some of which have since been lost.

His thesis was that the Inca believed a host of nature deities controlled their lives and needed to be appeased by careful attention to prescribed rituals and sacrifices. With respect to their customs, Cobo held that the Inca craftsmen achieved marvelous results with minimal equipment. For example, he points out that with simple tools the Inca's weavers made the most extraordinary cloth, the stonemasons constructed incredibly fine walls, and the farmers raised excellent crops.

While interviewing the Indians, Father Cobo soon realized that the peasants had forgotten all about the royal Inca political and religious institutions; therefore, he interviewed only descendants of the Inca on that subject. However, he collected much information on the customs of the common people. Many of these practices can still be observed today. For example, in the countryside near Cuzco, I have seen peasant houses with thatched roofs just as Cobo describes. Each house has a cooking fire inside and no chimney. The smoke rises through the thatch. (See Book II, Chapter 3.)

In other cases some changes have occurred. Father Cobo provides excellent descriptions of the monuments at Cuzco, especially the Temple of the Sun, Copacabana, Tiahuanaco, and Pachacama as he saw them in the early part of the seventeenth century. This information is very useful in determining how these monuments have been modified subsequently. For example, even my own casual observations at Tiahuanaco and Pachacama indicate that restoration has greatly altered these sites. Scholars need to do more studies using Cobo's material and that of others, as well as on-site research, if they are to continue the work of scholars like Max Uhle, who did an exemplary study back in 1896. (See Book I, Chapter 17, note 40.)

With respect to his written sources on the Incas, Cobo gives very general information. In the prologue to his Historia (not translated) he acknowledges having a manuscript copy of Pedro Pizarro's chronicle, Relacion del descubrimiento y conquista de los reinos del Peru . . ., dated 1571, first published in Madrid, 1844. Cobo also makes general reference to sources at the beginning of his account on the Incas (See History of the Inca Empire, Book II, Chapter 2.) Here Cobo indicates that he had manuscript copies of the account by the Licentiate Juan Polo de Ondegardo. In fact, he probably possessed the complete version of his treatise on Inca religion compiled in 1559, an extract of which was published in Lima in 1585 with the title Errores y supersticiones de los indios, as well as the work by Cristobal de Molina of Cuzco, Relacion de las fabulas y ritos de los Incas, written in 1575, published in Santiago, 1913. Additionally, he had a manuscript of a report done for the Viceroy Francisco de Toledo. This Toledo report, incidentally, has not been found by modern scholars.

In the same place mentioned above, Cobo also

acknowledges his two most important published sources: the Historia natural

y moral de las Indias (Seville, 1590), by the Jesuit scholar José de

Acosta![]() , and the Comentarios reales . . . de los Yncas (Lisbon, 1609),

by the mestizo author Garcilaso de la Vega Inca.

, and the Comentarios reales . . . de los Yncas (Lisbon, 1609),

by the mestizo author Garcilaso de la Vega Inca.

Working within an overall framework of his own, Cobo turned to Acosta for the

philosophical background of idolatry. Cobo drew on Polo de Ondegardo for the

hierarchy of the gods, his insistence on the importance of sacrifice,

including human sacrifice, and his general ideas concerning the multitude of

huacas or shrines and other sacred objects. Cobo used Cristobal de Molina of

Cuzco for some legends, Inca rituals, and ceremonies as well as prayers. He

followed Pedro Pizarro for material such as the worship of the dead (Book I,

Chapter 10) and the shrine of Apurima (Book I, Chapter 20).

Although he used Garcilaso Inca's versions of some legends and myths, Cobo, nevertheless, implicitly rejects the Garcilasan interpretation of Inca religion as a kind of primitive Christianity. For example, Garcilaso states that the Incas had no human sacrifice. Cobo explains in detail how Inca human sacrifices were performed, and for what reasons. Archaeological evidence corroborates Cobo's explanation. Garcilaso stated that the Incas had only one god, Pachacama. But Cobo, correctly, discusses hundreds of Inca deities, their powers, and the sacrifices made to them.

Father Cobo used some sources without acknowledging them at all, a common practice at the time. For example, he based his material about the shrine at Copacabana (Book I, Chapter 18) on the work of the Augustinian Friar Alonso Ramos Gavilan, Historia del celebre santuario de Nuestra Senora de Copacabana... Lima, 1621. Cobo also appears to have had an unidentified manuscript for his account of the shrines of Cuzco (Book I, Chapter 13-16). New research has discredited the theory that Cobo's source on the shrines was written by either Polo de Ondegardo or Molina of Cuzco. (See Book I, note 30). Whatever the sources may have been, it is clear that Father Cobo has preserved invaluable material for the study of the Incas.

Although Father Cobo did careful historical research, he still retained the mentality of a seventeenth-century priest. He accepted the authority of the Bible on all matters, historical or otherwise. For example, on hearing a fable which included destruction by water, he connects it with the Biblical Flood, thinking that the Indians had some knowledge of the Flood. He identifies the Inca gods with the devil. Cobo did not think these deities were merely figments of the Indian's imagination. He truly believed they were manifestations of the devil with certain supernatural powers. Hence he felt compelled to condemn native beliefs.

Cobo believed the book of Genesis explained the creation of the world and the beginnings of civilization. This influenced his interpretation of the native myths. He considers most native myths nonsense because they differ from the stories in Genesis. Nevertheless, Father Cobo was deeply interested in Inca religion, and he compiled a very reliable and comprehensive study on the subject.

Father Cobo enlivens his account with interesting tales. He evidently told these stories as he got them in order to entertain the reader. But he always uses them to prove a point. For example, at one point he recounts a Spanish folk tale about the treasures buried at Tiahuanaco to teach a lesson about covetousness. This story indicates that the ancient rulers of Tiahuanaco were reputed to have had vast treasures (Book I, Chapter 19). He tells another fascinating story about a wondrous cure (Book II, Chapter 10) thus illustrating indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants. In order to show that at Tiahuanaco cut stones were found everywhere, he tells how the priest had his native sculptor dig just where they happened to be standing, and they found stones suitable for statues (Book I, Chapter 19). Professor John Rowe has investigated this matter, and he found that "the story is even better than Cobo thought. Those statues of San Pedro and San Pablo are still in front of the church, and they are genuine ancient statues, carved in the Pucara style. The Indian sculptor dug down and found two statues and palmed them off on the priest as his work" (personal communication).

Finally, I will say a word about the place Father Cobo's work occupies among the many sources on the Inca. There have been two periods of intense activity in Inca research: the second half of the sixteenth century up to the early seventeenth century and the twentieth century. During the first period, the novelty of initial contact and the desire to explain the new reality inspired the production of chronicles like those of Juan Polo de Ondegardo and José de Acosta.

During the second period, the development of scientific anthropology and archaeology resulted in much serious research on the Inca. Father Cobo comes at the end of the first period, and his method is that of a serious historian who has compiled and analyzed invaluable documents on the Inca. However, Cobo's manuscripts remained virtually unknown until the first publication in Spanish of the Historia del Nuevo Mundo came out in Seville between 1890 and 1893. This puts his work at the beginning of modern scientific research just before 1895, when another European working in Peru, the German archaeologist Max Uhle, started the field work and research with accounts by Cobo and others that greatly enlarged our understanding of the Inca Empire.

Through his training as a Jesuit and his keen observations gleaned from many parts of Peru, Father Cobo developed into an outstanding scholar. Carefully using original sources and personal experience, he prepared one of our most important and extensive sources on the Inca. Though earlier editions are based on imperfect copies, the present translation was based on the original. It completes the work initiated with the History of the Inca Empire and offers the reader an exciting new source in English on the religion and customs of the Incas.

http://www.utexas.edu

Bernabé Cobo

Born at Lopera in Spain, 1580; died at Lima, Peru, 9 October, 1657. He went to America in 1596, visiting the Antilles and Venezuela and landing at Lima in 1599. Entering the Society of Jesus, 14 October, 1601, he was sent by his superiors in 1615 to the mission of Juli, where, and at Potosí, Cochabamba, Oruro, and La Paz, he laboured until 1618. He was rector of the college of Arequipa from 1618 until 1621, afterwards at Pisco, and finally at Callao in the same capacity, as late as 1630.

He was then sent to Mexico, and remained there until

1650, when he returned to Peru. Such in brief was the life of a man whom the

past centuries have treated with unparalleled, and certainly most ungrateful,

neglect. Father Cobo was beyond all doubt the ablest and most thorough student

of nature and man in Spanish America during the seventeenth century. Yet, the

first, and almost only, acknowledgement of his worth dates from the fourth

year of the nineteenth century. The distinguished Spanish botanist Cavanilles

not only paid a handsome tribute of respect to the memory of Father Cobo in an

addressed delivered at the Royal Botanical Gardens of Madrid, in 1804, but he

gave the name of Cobaea to a genus of plants belonging to the Polemoniaceae of Mexico, Cobaea

scandens![]() being its most striking

representative.

being its most striking

representative.

Cobo's long residence in both Americas (sixty-one years), his position as a priest and, several times, as a missionary, and the consequently close relations in which he stood to the Indians, as well as to Creoles and half-breeds, gave him unusual opportunities for obtaining reliable information, and he made the fullest use of these. We have from his pen two works, one of which (and the most important) is, unfortunately, incomplete. It is also stated that he wrote a work on botany in ten volumes, which, it seems, is lost, or at least its whereabouts is unknown today.

Of his main work, to which

biographers give the title "Historia general de las Indias", and

which he finished in 1653, only the first half is known and has appeared in

print (four volumes, at Seville, 1890 and years succeeding). The remainder, in

which he treats, or claims to have treated, of every geographical and

political subdivision in detail, has either never been finished, or is lost.

His other book appeared in print in 1882, and forms part of the "History

of the New World" mentioned, but he made a separate manuscript of it in

1639, and so it became published as "Historia de la fundación de

Lima", a few years before the publication of the principal

manuscript.

"The History of the New World" places Cobo, as a chronicler and didactic writer, on a plane higher than that occupied by his contemporaries not to speak of his predecessors. It is not a dry and dreary catalogue of events; man appears in it on a stage, and that stage is a conscientious picture of the nature in which man has moved and moves. The value of this work for several branches of science (not only history) is much greater than is believed.

The book, only recently published, is very little known and appreciated. The "History of the New World" may, in American literature, be compared with one work only, the "General and Natural history of the Indies" by Oviedo. But Oviedo wrote a full century earlier than Cobo, hence the resemblance is limited to the fact that both authors seek to include all Spanish America -- its natural features as well as its inhabitants. The same may be said of Gomara and Acosta.

Cobo enjoyed superior advantages and made good use of them. A century more of knowledge and experience was at his command. Hence we find in his book a wealth of information which no other author of his time imparts or can impart. And that knowledge is systematized and in a measure co-ordinated. On the animals and plants of the new continent, neither Nieremberg, nor Hernandez, nor Monardes can compare in wealth of information with Cobo. In regard to man, his pre-Columbian past and vestiges, Cobo is, for the South American west coast, a source of primary importance. We are astonished at his many and close observations of customs and manners. His description of some of the principal ruins of South America are usually very correct. In a word it is evident from these two works of Cobo that he was an investigator of great perspicacity, and, for his time, a scientist of unusual merit.

Catholic Encyclopedia

Bernabé Cobo (Lopera, Jaén , España, 1580 - Lima , 9 de octubre 1657) fue un cronista y científico jesuita español. A los 15 años embarcó para América y luego de recorrer las Antillas, Guatemala, Nueva Granada y Venezuela se dirigió al Perú, llegando a Lima en 1598. Ingresó al Colegio Real de San Martín en 1599 según Ruben Vargas Ugarte en calidad de fámulo dado que no figura en el catálogo de alumnos regulares. Se ordenó de sacerdote en 1615 y fue enviado a Juli, Potosí, Cochabamba y la Paz. En 1621 fue nombrado Rector del Colegio de Arequipa, en 1626 se trasladó al Colegio de los Jesuitas de Pisco y en 1630 se le nombró Rector del Colegio del Callao. En 1631 fue enviado a México donde permaneció hasta 1642.

En su obra Historia del Nuevo Mundo hace importantes aportes a las ciencias naturales, especialmente a la botánica. Esta obra fue hallada en la Biblioteca de la Iglesia de San Ocacio en Sevilla en 1893 de aquí solo se ha podido publicar el primer tomo y parte del segundo. El tercer tomo que trata sobre México no ha sido hallado. En el primer tomo es de particular relevancia la descripción detallada que hace del sistema de ceques del Cuzco.

Bernabé

Cobo

1580-1657

A pesar de no conocer más que la primera de las tres partes en las que el jesuita dividió su estudio sobre el Nuevo Mundo, sabemos que cada una de ellas versaba sobre los siguientes temas:

- el estudio de América antes del descubrimiento o lo que es igual, el conocimiento de las culturas y naturaleza americanas anteriores a la llegada de los españoles;

- la historia de la conquista y colonización del Perú y de las latitudes americanas más meridionales;

- por último, en la tercera parte, trató de la conquista y colonización de otras zonas del Nuevo Mundo, Molucas, Filipinas, etc.

Nació Bernabé Cobo en Lobera (Jaén) en 1580, y marchó a las Indias a los dieciséis años. En 1599 se matriculó en el Colegio de San Martín en Lima, ingresando dos años después como novicio en la Compañía de Jesús, que regentaba el Colegio. No hizo sus votos hasta el año 1622.

Realizó numerosos viajes: Antillas, Virreinato del Perú, Nueva España y Centroamérica, y en 1653 completó su monumental Historia del Nuevo Mundo, fruto de una constante y minuciosa labor de ocho lustros. Sin embargo, esta descomunal obra quedó inédita y en gran parte se perdió. Por fortuna para la historiografía científica se conservó la primera parte: 14 libros sobre la historia natural de aquellos territorios.

Aunque el botánico valenciano Antonio José Cavanilles (1745-1804) publicó algunos fragmentos de la obra de Cobo al iniciarse el siglo XIX, no fue sino el cartagenero Marcos Jiménez de la Espada (1831-1898), el más eminente de los científicos que participaron en la expedición al Pacífico (1862-1865) y gran defensor de la ciencia nacional, el que recuperó para la cultura española la obra del jesuita andaluz. En efecto, la Historia del Nuevo Mundo de Bernabé Cobo vio la luz por primera vez entre 1890 y 1893, en cuatro volúmenes, ilustrada y con anotaciones del eminente murciano.

El prólogo de su obra lo firma en julio de 1653 y quizá su muerte, en Lima en el año 1657, impidió la publicación de la misma. Hay que hacer notar que de los 77 años de vida, sesenta y uno los vivió en América.

A pesar de no conocer más que la primera de las tres partes en las que el jesuita dividió su estudio sobre el Nuevo Mundo, sabemos que cada una de ellas versaba sobre los siguientes temas: el estudio de América antes del descubrimiento o lo que es igual, el conocimiento de las culturas y naturaleza americanas anteriores a la llegada de los españoles; la historia de la conquista y colonización del Perú y de las latitudes americanas más meridionales; por último, en la tercera parte, trató de la conquista y colonización de otras zonas del Nuevo Mundo, Molucas, Filipinas, etc.

Suele atribuirse a Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) la primera descripción de los pisos de vegetación en los Andes, a principios del siglo XIX. Sin embargo, Bernabé Cobo, casi dos siglos antes, ya se ocupa de ellos.

Nuestro jesuita siempre muestra un gran interés por el ambiente en el que se desarrollan la vegetación y las especies animales. Tal es así que, la mejor manera que tiene de describir los “temples”, “grados” o “andenes” de los Andes es mediante su vegetación. El relato de Bernabé Cobo es eminentemente ecológico, zoogeográfico y fitogeográfico; no realiza descripciones de las especies vegetales de cada piso, las enumera; la finalidad del jiennense es la de explicar la presencia de diferentes plantas en relación con la altitud y el clima. De manera continuada refiere los distintos pisos de vegetación, desde arriba hacia abajo, dando cuenta, en cada “temple”, del clima, vegetación, fauna y asentamientos humanos más significativos.

Es importante referir que, de la misma forma que la mayor parte de los cronistas de Indias del siglo anterior, el P. Cobo nos cuenta sus propias observaciones, no refiere noticias de otros.

Como resumen, podemos decir que en el relato del P. Cobo apreciamos un conjunto de características que destaco a continuación:

a) Caracteriza nominalmente varios pisos de vegetación: la “puna brava”, la “puna”, el “páramo”, la “medio yunca”, etc.

b) En los distintos temples da detalles climáticos referentes a la humedad y la temperatura.

c) En los temples enumera especies vegetales propias del Perú y españolas.

d) Los diferentes pisos se distinguen del precedente, según se desciende, por el desarrollo de alguna especie que no se aprecia en el piso anterior o, si lo hace, no fructifica. Así, vemos que en el segundo se dan especies vegetales que no aparecen en el primero: papas, ocas, etc.; en el tercero se ven ya especies de maíz y lino, entre otras; en el cuarto ya se observan árboles frutales “de los de España”; en el quinto se dan “árboles que requieren más calor” y el último piso ya maduran los dátiles, plátanos y melones.

e) Cada uno de los andenes o temples es perfectamente localizable por los accidentes geográficos que cita o los asentamientos humanos.

f) La enumeración de la vegetación de los andenes nos proporciona detalles muy interesantes del grado de aclimatación de las especies que llevaron los españoles.

La obra del padre Cobo encierra otras muchas ideas originales que son e fruto de sus observaciones y experiencias, razonadas libremente, sin atenerse a las clásicas concepciones escolásticas o humanísticas (ni siquiera cita autoridades). Es pues la actitud característica de la Revolución científica del siglo XVII, hija del Renacimiento y el Humanismo pero que rompe con el mundo clásico al que da por superado.

Además, el estilo directo y la expresión clara y sencilla, sin pretensiones, nos hacen que el jesuita andaluz se encuentre cerca de nuestra actual sensibilidad sobre la naturaleza, otra importante razón para recomendar su lectura.

Francisco

Teixidó

Este artículo fue publicado el 23 Jun 2005 y ha sido leído 3897 veces

http://www.citologica.org

Biblioteca de Autores Españoles

Manuel Rivadeneyra

Manuel Rivadeneyra (Barcelona, 1805 - Madrid, 1 de abril de 1872), editor e impresor español. Hizo su aprendizaje como impresor con Antonio Bergnes y más tarde en París. Luego publicó el periódico barcelonés El Vapor. Con la idea de editar una colección de clásicos españoles (la después famosa BAE o Biblioteca de Autores Españoles) no dudó en emigrar dos veces a América con la intención de hacer fortuna para financiar su empresa. Viajó a Chile donde montó una imprenta en Valparaíso, compró el diario El Mercurio, publicó a su amigo Andrés Bello e introdujo las técnicas modernas de impresión de libros. En Chile y en 1841 nació su hijo Adolfo, que sería famoso orientalista.

Desde 1846 impulsó en Madrid la edición de la Biblioteca de Autores Españoles, que puso bajo la dirección de Buenaventura Carlos Aribau. En esta reimprimió en cuarto y con gran calidad las obras clásicas de la literatura española, añadiendo a veces obras inéditas o recuperando otras olvidadas. En esta biblioteca se forjó toda una generación de críticos y editores de literatura clásica española, con desiguales criterios ecdóticos. Ejemplares de esta obra por un valor se 400.000 reales fueron adquiridos para las bibliotecas del Estado.

El título completo es Biblioteca de Autores Españoles desde la formación del lenguaje hasta nuestros días, Madrid: Rivadeneyra, 1846-1888. En 1905 Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo quiso ampliar la colección con un el título de Nueva Biblioteca de Autores Españoles (dirigida por Menéndez Pelayo hasta el vol. XX), Madrid: Bailly-Baillière, 1905-1918 (26 vols.). A partir de 1954 la continuó la Editorial Atlas hasta un número total de más de 300 vols.

Rivadeneyra abordó la publicación de las obras completas de los autores, si bien este empeño resulta frustrado en muchas ocasiones; además los textos no siempre están editados con el rigor debido. Los estudios preliminares son útiles, pero, en ocasiones, han quedado anticuados - como por otra parte resulta comprensible -. En algunos casos, y hasta fechas muy recientes, constituía una referencia inexcusable para conocer la literatura de un período (era el caso de la poesía del XVII o del XVIII, por ejemplo).

Rivadeneyra fue invitado por el infante Sebastián Gabriel de Borbón, prior de la orden de San Juan, para que trasladase su imprenta a la Cueva de Medrano en Argamasilla de Alba, a fin de hacer la famosa edición del Quijote de 1863, con prólogo del dramaturgo español Hartzenbusch.

Una vez fallecido, su hijo Adolfo Rivadeneyra (Santiago de Chile, 1841 - Madrid, 1882), orientalista y cónsul de España en Chile, continuó la colección y sus nietos hasta su conclusión en 1888. El 29 de septiembre de 1977 España emitió un sello postal de 7 pesetas reproduciendo un retrato de Rivadeneyra debido al pintor Federico Madrazo.

Cobaea scandens

Nome dato in onore del gesuita spagnolo Padre Bernabé Cobo, grande naturalista vissuto in Perù e in Messico; da qui proviene questo genere delle Polemoniaceae che comprende poche specie perenni, delicate, rampicanti per mezzo di viticci. Di esse solo una è introdotta e apprezzata nella coltivazione a scopo ornamentale, la Cobaea scandens, dal fiore campanulato, dal lungo picciuolo (somigliante a quello della Campanula medium), fornita alla base di un calice di cinque elementi espansi che formano un involucro simile a un piattino.

Inizialmente, allo sbocciare, la corolla è di color verde, poi, un po' alla volta, si tinge di viola porpora o di bianco crema. I singoli fiori non durano più di un giorno, ma in compenso la fioritura della pianta è continua da maggio a ottobre e talvolta anche durante l’inverno. È un rampicante sempreverde a rapida crescita, fino a 6-7 m di altezza. Si usa spesso per ricoprire le pareti di serre molto grandi: possono essere sufficienti solo 3 o 4 piante. Pur essendo perenne viene generalmente coltivata come annuale. Esistono anche la varietà a fiore bianco, flore albo, i cui semi si distinguono per il colore chiaro, mentre quelli del tipo a fiori violetti sono più scuri, e la varietà. variegata a foglie screziate.

I semi si devono porre a germinare in febbraio, o comunque quando la temperatura non scende sotto i 10-13°C; si può anche ritardare la semina fino ad aprile, e allora la si effettua in cassone freddo. Le piantine ottenute si invasano singolarmente dopo che avranno emesso la seconda o la terza foglia. In giugno potranno essere piantate all'aperto, in un angolo ombroso del giardino, o in una serra fredda.

La cobée grimpante est une plante grimpante, herbacée, de la famille des Polémoniacées, cultivée pour l'ornement des jardins. Le genre du nom "cobée" est incertain : Il est masculin pour certains dictionnaires usuels, alors qu'on voit généralement écrit "cobée grimpante" sur les sachets de graines.

Elle est une plante grimpante à tiges grêles volubiles pouvant atteindre jusqu'à 8 à 10 m de long. Feuilles pennées à 3 paires de folioles ovales, munies de vrilles. Les fleurs violettes assez grandes (7 à 8 cm de long sur 3 à 5 cm de diamètre) apparaissent de juillet à octobre à l'aisselle des feuilles, solitaires. Elles ont une corolle en forme de campanule.

La plante est vivace dans son aire d'origine, ou en culture abritée en serre. Elle est cultivée en plein air comme une plante annuelle. Plante originaire du Mexique central. Elle est largement cultivée dans tous les continents, et s'est naturalisée dans les régions tropicales du nouveau monde Cultivée comme plante ornementale pour son aspect très décoratif. Son développement très rapide en fait une plante idéale pour garnir treillages et tonnelles.