Lessico

Elio Dionisio

Grammatico

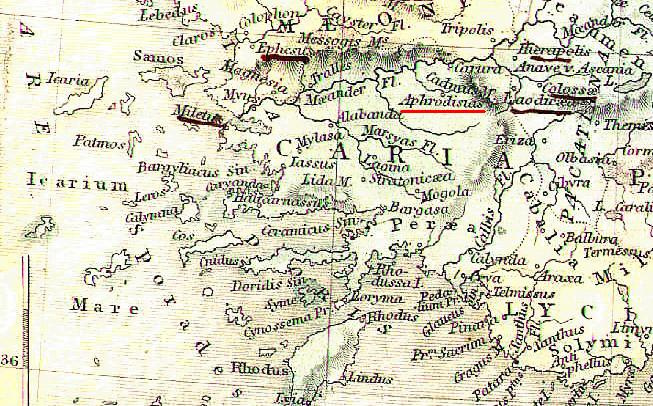

greco, detto l’Atticista![]() , nato ad Alicarnasso in Asia Minore (II sec. dC),

vissuto sotto Adriano

, nato ad Alicarnasso in Asia Minore (II sec. dC),

vissuto sotto Adriano![]() ,

autore di un lessico delle locuzioni attiche (in 5 libri, cui seguì una

seconda edizione anch’essa in 5 libri), largamente utilizzata dai

lessicografi posteriori, in cui illustrava il patrimonio linguistico attico,

specialmente dei poeti.

,

autore di un lessico delle locuzioni attiche (in 5 libri, cui seguì una

seconda edizione anch’essa in 5 libri), largamente utilizzata dai

lessicografi posteriori, in cui illustrava il patrimonio linguistico attico,

specialmente dei poeti.

Aelius Dionysius was a Greek rhetorician from Halicarnassus, who lived in the time of the emperor Hadrian. He was a very skilful musician, and wrote several works on music and its history. It is commonly supposed that he was a descendant of the elder Dionysius of Halicarnassus, author of the Roman Archaeology. Respecting his life nothing further is known. The following works, which are now lost, are attributed to him by the ancients:

A

dictionary of Attic words (᾿Αττικά ὀνόματα) in five books,

dedicated to one Scymnus. Photius![]() speaks in high terms of its usefulness, and states that Aelius Dionysius

himself made two editions of it, the second of which was a great improvement

upon the first. Both editions appear to have been extant in the time of

Photius. It seems to have been owing to this work that Aelius Dionysius was

called sometimes by the surname of Atticista

speaks in high terms of its usefulness, and states that Aelius Dionysius

himself made two editions of it, the second of which was a great improvement

upon the first. Both editions appear to have been extant in the time of

Photius. It seems to have been owing to this work that Aelius Dionysius was

called sometimes by the surname of Atticista![]() .

.

A history of music (μουσική ἱστορία) in 36 books, with accounts of citharoedi, auletae, and poets of all kinds.

Ῥυθμικά ὑπομνήματα, in 24 books.

Μουσικῆς παιδεία ἢ διατριβαί, in 22 books.

A work in five books on what Plato had said about music in his πολιτεία.

Johannes

Meursius was of opinion that this Dionysius was the author of the work περί ἀκλίτων ῥημάτων καὶ ἐγκλινομένων λέξεων, which

was published by Aldus Manutius![]() in

Venice in 1496, in a volume entitled Horti

Adonidis; but there is no evidence for this supposition.

in

Venice in 1496, in a volume entitled Horti

Adonidis; but there is no evidence for this supposition.

Dictionary

of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology

William Smith, Boston,

1867

L'Atticismo

è un movimento retorico-stilistico nato a Roma nel I secolo aC in opposizione

agli eccessi della scuola dell'Asianesimo di Ortensio Ortalo e di Cicerone![]() ,

e convenzionalmente identificato con l'indirizzo della scuola di Alessandria.

I suoi fautori) rivendicavano la purezza linguistica dell'attico, in

opposizione all'inserimento di elementi ionici (Asiani).

,

e convenzionalmente identificato con l'indirizzo della scuola di Alessandria.

I suoi fautori) rivendicavano la purezza linguistica dell'attico, in

opposizione all'inserimento di elementi ionici (Asiani).

Ben

presto l'opposizione si spostò da un piano linguistico-grammaticale a un

piano più ampio di natura retorica: alle opposte posizioni grammaticali si

sovrapposero anche opposte posizioni stilistiche. Gli Atticisti sostenevano

un'imitazione dei classici austera, ascetica, quasi confinata - scrive

Cicerone - al trattamento artistico del genere umile (Orator 75).

Modello di questo stile semplice e di un attico puro era Lisia![]() (445-380 aC), così come Senofonte

(445-380 aC), così come Senofonte![]() ,

le commedie di Menandro

,

le commedie di Menandro![]() e i retori e grammatici puristi Apollodoro di Pergamo (ca. 104 - ca. 22 aC) e

Dionisio o Dionigi di Alicarnasso (I sec. aC). Gli Asiani invece apprezzavano

un'oratoria più artificiosa, ricca di formule ritmiche ed espedienti tecnici.

A questa scuola va ricondotta anche la cosiddetta teoria analogista, sostenuta

anche da Cesare

e i retori e grammatici puristi Apollodoro di Pergamo (ca. 104 - ca. 22 aC) e

Dionisio o Dionigi di Alicarnasso (I sec. aC). Gli Asiani invece apprezzavano

un'oratoria più artificiosa, ricca di formule ritmiche ed espedienti tecnici.

A questa scuola va ricondotta anche la cosiddetta teoria analogista, sostenuta

anche da Cesare![]() (De analogia): purista e conservatrice, la lingua deve fondarsi su

norme precise e sul rispetto di modelli conosciuti.

(De analogia): purista e conservatrice, la lingua deve fondarsi su

norme precise e sul rispetto di modelli conosciuti.

Atticism (meaning favouring Attica, the region that includes Athens in Greece) was a rhetorical movement that began in the first quarter of the first century BC; it may also refer to the wordings and phrasings typical of this movement, in contrast with spoken Greek, which continued to evolve in directions guided by the common usages of Hellenistic Greek. Atticism was portrayed as a return to Classical methods after what was perceived as the pretentious style of the Hellenistic, Sophist rhetoric and called for a return to the approaches of the Attic orators.

Although the plainer language of Atticism eventually became as belabored and ornate as the perorations it sought to replace, its original simplicity meant that it remained universally comprehensible throughout the Greek world. This helped maintain vital cultural links across the Mediterranean and beyond. Admired and popularly imitated writers such as Lucian also adopted Atticism, so that the style survived until the Renaissance, when it was taken up by non-Greek students of Byzantine expatriates. Renaissance scholarship, the basis of modern scholarship in the west, nurtured strong Classical and Attic prejudices, continuing Attic snobbishness for another four centuries.

Represented at its height by rhetoricians such as Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and grammarians such as Herodian and Phrynichus Arabius at Alexandria, this tendency prevailed from the second century BC onward, and with the force of an ecclesiastical dogma controlled all subsequent Greek culture, even so that the living form of the Greek language, even then being transformed into modern Greek, was quite obscured and only occasionally found expression, chiefly in private documents, though also in popular literature.