Lessico

Mirra

Il termine mirra viene dal latino murra/murrha/myrra/myrrha, a sua volta derivato dal greco mýrrha di origine semitica occidentale dalla radice mrr ‘essere amaro’ per il gusto della sua radice: I Fenici hanno trasmesso ai Greci pianta, gomma aromatica e nome.

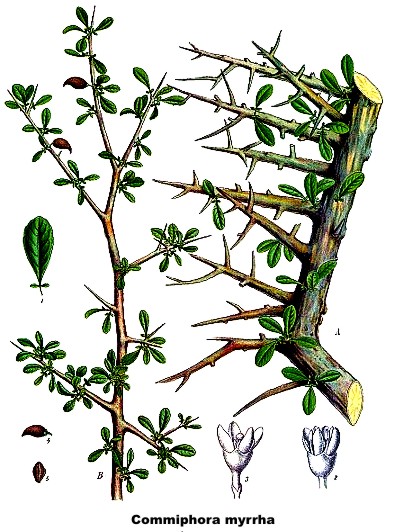

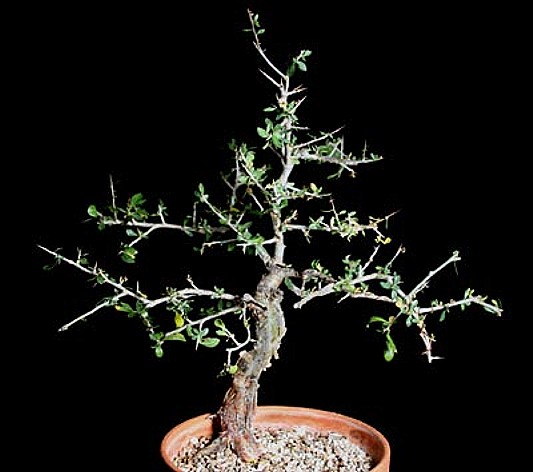

La mirra è una gommoresina aromatica, estratta da un albero o arbusto del genere Commiphora, della famiglia delle Burseraceae. Esistono circa cinquanta specie di Commiphora, ripartite sulle rive del mar Rosso, in Senegal, in Madagascar e in India. La specie più usata per la produzione della mirra è la Commiphora myrrha, un tempo nota come Myrrhis odorata (diffusa in Somalia, Etiopia, Sudan, penisola arabica): alla fine dell'estate l'arbusto si copre di fiori e sul tronco compaiono una serie di noduli, dai quali cola la mirra, in piccole gocce gialle, che vengono raccolte una volta seccate. Un'altra sorgente della mirra è la Commiphora abyssinica, albero spinoso alto sino a dieci metri, originario dell'Abissinia e dell'Egitto. Una gomma simile, il balsamo della Mecca, è prodotta dalla Commiphora gileadensis (in passato denominata Commiphora opobalsamum).

La storia

della mirra è parallela a quella dell'incenso![]() : era già conosciuta

nell'antico Egitto, dove costituiva uno dei componenti del kyphi

: era già conosciuta

nell'antico Egitto, dove costituiva uno dei componenti del kyphi![]() o cifi (in greco kÿphi) ed era

utilizzata nell'imbalsamazione. Nella Bibbia è uno dei principali componenti

dell'olio santo per le unzioni (Esodo, XXX,23), ma anche un profumo, citato

sette volte nel Cantico dei Cantici.

o cifi (in greco kÿphi) ed era

utilizzata nell'imbalsamazione. Nella Bibbia è uno dei principali componenti

dell'olio santo per le unzioni (Esodo, XXX,23), ma anche un profumo, citato

sette volte nel Cantico dei Cantici.

Nel Vangelo secondo Matteo (2,11) fu uno dei doni portati dai Re Magi al Bambino Gesù: "Entrati nella casa, videro il bambino con Maria sua madre, e prostratisi lo adorarono. Poi aprirono i loro scrigni e gli offrirono in dono oro, incenso e mirra."

Secondo la tradizione simboleggia l'unzione di Cristo, o l'espiazione dei peccati tramite la sofferenza e la morte corporale. Infatti Marco (15,20-24) racconta: [20] Dopo averlo schernito, lo spogliarono della porpora e gli rimisero le sue vesti, poi lo condussero fuori per crocifiggerlo. [21] Allora costrinsero un tale che passava, un certo Simone di Cirène che veniva dalla campagna, padre di Alessandro e Rufo, a portare la croce. [22] Condussero dunque Gesù al luogo del Gòlgota, che significa luogo del cranio, [23] e gli offrirono vino mescolato con mirra, ma egli non ne prese. [24] Poi lo crocifissero e si divisero le sue vesti, tirando a sorte su di esse quello che ciascuno dovesse prendere.

Nella Grecia antica la mirra era ampiamente utilizzata, fino a mescolarla con il vino e un episodio mitologico narra della

sua origine, legandola a Mirra figlia del re di Cipro e madre di Adone![]() .

.

La mirra si presenta sotto forma di grani tondeggianti, o frammenti irregolari di colore rossastro all'esterno e quasi bianchi all'interno. Ha un lieve odore aromatico e sapore amaro; è composta da tre frazioni: un olio etereo contenente fenoli e terpeni, una resina costituita da acidi organici caratteristici e una gomma formata per la maggior parte da pentosani e galattano. La mirra fin da tempi remoti fu usata come profumo e sostanza purificante. Come s'è detto, nell'antico Egitto veniva adoperata per le imbalsamazioni. Nella farmacopea popolare fu usata come astringente e antisettico; attualmente il suo uso è limitato all'industria dei profumi.

Dalla distillazione della mirra si ricava un olio essenziale, ottimo rimedio per diversi problemi fisici, soprattutto se inerenti all'apparato digerente. Da oltre 3000 anni è infatti utilizzata come disinfettante delle vie intestinali e anche come conservante per cibi rapidamente deperibili.

Commiphora myrrha

Myrrh is a reddish-brown resinous material, the dried sap of the tree Commiphora myrrha, native to Yemen, Somalia and the eastern parts of Ethiopia. The sap of a number of other Commiphora and Balsamodendron species are also known as myrrh, including that from Commiphora erythraea (sometimes called East Indian myrrh), Commiphora opobalsamum and Balsamodendron kua. Its name entered English via the Ancient Greek, mýrrha , which is probably of Semitic origin. Myrrh is also applied to the potherb Myrrhis odorata otherwise known as "Cicely" or "Sweet Cicely".

High quality myrrh can be identified through the darkness and clarity of the resin. However, the best method of judging the resin's quality is by feeling the stickiness of freshly broken fragments directly to determine the fragrant-oil content of the myrrh resin. The scent of raw myrrh resin and its essential oil is sharp, pleasant, somewhat bitter and can be roughly described as being "stereotypically resinous". When burned, it produces a smoke that is heavy, bitter and somewhat phenolic in scent, which may be tinged with a slight vanillic sweetness. Unlike most other resins, myrrh expands and "blooms" when burned instead of melting or liquefying.

The scent can also be used in mixtures of incense, to provide an earthy element to the overall smell, and as an additive to wine, a practice alluded to by ancient authorities such as Fabius Dorsennus. It is also used in various perfumes, toothpastes, lotions, and other modern toiletries.

Myrrh was used as an embalming ointment and was used, up until about the 15th century, as a penitential incense in funerals and cremations. The "holy oil" traditionally used by the Eastern Orthodox Church for performing the sacraments of chrismation and unction is traditionally scented with myrrh, and receiving either of these sacraments is commonly referred to as "receiving the Myrrh".

Myrrh is a constituent of perfumes and incense, was highly valued in ancient times, and was often worth more than its weight in gold. The Greek word for myrrh, mýrrha, came to be synonymous with the word for "perfume". In Ancient Rome myrrh was priced at five times as much as frankincense, though the latter was far more popular. Myrrh was burned in ancient Roman funerals to mask the smell emanating from charring corpses. It was said that the Roman Emperor Nero burned a year's worth of myrrh at the funeral of his wife, Poppaea.

In Christian Scriptures, Myrrh was one of the gifts of the Magi to the infant Jesus according to Matthew, and is cited in Mark as an intoxicant that was offered to Jesus during the crucifixion:

Then, opening their treasures, they offered him gifts, gold and frankincense and myrrh. (Matthew 2:11b, RSV)

And they brought him to the place called Gol'gotha (which means the place of a skull). And they offered him wine mingled with myrrh; but he did not take it. (Mark 15:22,23 RSV)

Because of both of these contexts, myrrh is a common ingredient in incense offered during Christian liturgical celebrations (see Thurible). In Roman Catholic liturgical tradition, pellets of myrrh are traditionally placed in the Paschal candle during the Easter Vigil.

In Eastern Christianity, the use of incense is much more frequent than in the West. In some traditions, special emphasis is placed on the offering of incense at Vespers and Matins, because of the Old Testament regulation regarding the evening and morning offering of incense.

Because myrrh was the primary ingredient in the anointing oil God commanded Moses to make (Exodus 30:23-33), it is used in the preparation of chrism which is used by many churches, both Eastern and Western.

In Chinese medicine, myrrh is classified as bitter, spicy, neutral in temperature and affecting the heart, liver, and spleen meridians. Its uses are similar to those of frankincense, with which it is often combined in decoctions, liniments and incense. Myrrh is said to be blood-moving, while frankincense is said to move the Qi more, and is better for arthritic conditions. It is said to be useful for amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, menopause and uterine tumors, as it is said to purge stagnant blood out of the uterus. Myrrh is said to help toothache pain, and can be used in liniment for bruises, aches and sprains. Myrrh is most commonly used in Chinese medicine for rheumatic, arthritic and circulatory problems. It is combined with such herbs as notoginseng, safflower stamens, Angelica sinensis, cinnamon and Salvia miltiorrhiza, usually in alcohol, and used both internally and externally.

Myrrh is used more frequently in Ayurveda, Unani medicine and Western herbalism, which ascribe to it tonic and rejuvenative properties. A related species, known as guggul in Ayurvedic medicine is considered one of the best substances for the treatment of circulatory problems, nervous system disorders and rheumatic complaints, Myrrh (Daindhava) is used in many rasayana formulas in Ayurveda.

However rasayana herbs have special processing. Outside of this form myrrh is said to be contraindicated for pregnant women or women with excessive uterine bleeding, and not be used with evidence of kidney dysfunction or stomach pain.

In western pharmacy, Myrrh is used as an antiseptic and is most often used in mouthwashes, gargles and toothpastes for prevention and treatment of gum disease. Myrrh is currently used in some liniments and healing salves that may be applied to abrasions and other minor skin ailments. It is also used in the production of Fernet Branca.

Kyphi is a compound incense that was used in ancient Egypt for religious and medical purposes. The term "kyphi" is Greek and a transcription of the ancient Egyptian term kp.t.

The earliest reference to kyphi is found in the Pyramid Texts: it is listed among the goods that the king will enjoy in the afterlife. Papyrus Harris I records the donation and delivery of herbs and resins for its manufacture in the temples under Ramses III. Instructions for the preparation of kyphi and lists of ingredients are found among the wall inscriptions at the temples of Edfu and Dendera in upper Egypt. The Egyptian priest Manetho is known to have written a treatise called Preparation of Kyphi-Recipes, but no copy of this work survives.

Greek physicians studying the Egyptian pharmacopoeia took interest in kyphi's reputation as a medicine. Dioscorides set forth the preparation of kyphi in his Materia Medica and this is thought to be the first Greek description of the material. Galen preserves a medical poem about kyphi from Damocrates, who in turn credits Rufus of Ephesus for the formula.

In Isis and Osiris the historian Plutarch comments that Egyptian priests burned incense three times a day: frankincense at dawn, myrrh at mid-day, and kyphi at dusk. He reports that kyphi had sixteen ingredients and adds "These are compounded, not at random, but while the sacred writings are being read to the perfumers as they mix the ingredients." Plutarch further notes that the mixture was used as "a potion and a salve". The seventh century physician Paul of Aegina records a "lunar" kyphi of twenty-eight ingredients and a "solar" kyphi of thirty-six.

All recipes for kyphi mention wine, honey and raisins. Other identifiable ingredients include

cinnamon

and cassia bark,

the aromatic rhizomes of cyperus and sweet flag,

cedar,

juniper berry, and

resins and gums such as frankincense, myrrh, benzoin resin and mastic.

Some ingredients remain obscure. Greek and Aramaic recipes mention aspalathos, which Pliny describes as the root of a thorny shrub. Scholars do not agree on the identity of this shrub: Alhagi maurorum, Convolvulus scoparius, Calicotome villosa, Genista acanthoclada and most recently Capparis spinosa have been suggested. The Egyptian recipes similarly list several ingredients whose botanical identity is uncertain. Spikenard is listed as an ingredient in some recipes.

The manufacture of kyphi as given in the Edfu text involves blending and aging of sixteen ingredients in sequence. The result was rolled into balls and placed on hot coals to release a perfumed smoke.

As with other facets of Ancient Egypt, kyphi has attracted commercial, religious and academic interest. Simplified recipes for kyphi have been published for ceremonial use by neo Pagans and therapeutic use by practitioners of aromatherapy. Several firms offer commercial versions of kyphi for use as incense or perfume.