Lessico

Pitagora

Icones veterum aliquot ac recentium Medicorum

Philosophorumque

Ioannes Sambucus / János Zsámboky![]()

Antverpiae 1574

Filosofo

greco (Samo tra il 580 e il 570 - Metaponto prov. di Matera ca. 497 aC). Figlio di Mnesarco di

Samo, emigrò verso il 535 dalla sua città a Crotone in Calabria. Non scrisse nulla e già

dall'antichità la sua vita fu avvolta dalla leggenda; si parlò di lui come

di un dio, e di suoi prodigi. Diogene Laerzio![]() ,

scrittore greco del III secolo dC, ne scrisse la biografia contenuta nella sua

celebre opera Le vite, le opinioni, gli apoftegmi dei filosofi celebri

e la riportiamo in calce nella traduzione inglese di Yonge (1853)

,

scrittore greco del III secolo dC, ne scrisse la biografia contenuta nella sua

celebre opera Le vite, le opinioni, gli apoftegmi dei filosofi celebri

e la riportiamo in calce nella traduzione inglese di Yonge (1853)![]() .

.

A Crotone![]() Pitagora fondò un sodalizio in cui religione, scienza e politica si fondevano in un

ideale di vita che ebbe molta influenza nella Magna Grecia; appare inoltre

assai probabile che Pitagora sia venuto in contatto con le culture egiziana e

mesopotamica e forse anche con quella indiana.

Pitagora fondò un sodalizio in cui religione, scienza e politica si fondevano in un

ideale di vita che ebbe molta influenza nella Magna Grecia; appare inoltre

assai probabile che Pitagora sia venuto in contatto con le culture egiziana e

mesopotamica e forse anche con quella indiana.

Quando una congiura costrinse Pitagora a ritirarsi a Metaponto, la società pitagorica si disperse, per ricostituirsi più tardi a Taranto, dove l'insegnamento pitagorico durò sino al sec. IV aC. I suoi discepoli continuarono soprattutto i suoi studi delle matematiche e dell'astronomia.

Pythagoras

Pythagoras (Graece: Πυθαγόρας), philosophus et mathematicus Graecus, vixit circa 582 a.C.n. – 500 a.C.n. Pythagoras sententiam pythagoras facit.

Scripta Pythagorae tributa - Temporibus posterioribus multa praecepta, nonnulla etiam opera in formam librorum reducta, Pythagorae tributa sunt.

Liber de mirabilia plantarum

(aliter Cleemporo tributus) citatur:

Plinius, Naturalis historia 20. 78, 101, 134, 185, 192, 219, 236;

21.109; 24.116, et praecipue 24.156-160; 25.13 (citatur etiam in argumentis

octo librorum 20-27).

Geoponica 2.35.6, 8.42.

Liber de scilla:

Plinius, Naturalis historia 19.94.

Liber aut praecepta

Pythagoricorum:

Plinius, Naturalis historia 22.20.

Geoponica 12.13.2.

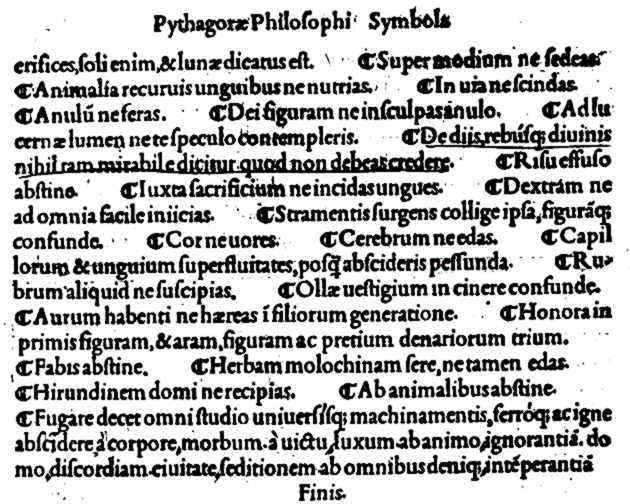

Che ne faceva Pitagora del gallo?

da Veterum illustrium philosophorum etc. imagines

(1685)

di Giovanni Pietro Bellori (Roma 1613-1696)

Come

possiamo dedurre dai Symbola Pythagorae tradotti da Marsilio Ficino![]() ,

è chiaramente sancito da Pitagora che si può benissimo allevare un gallo, ma

che non va usato nei sacrifici, essendo sacro al sole e alla luna: Gallum

nutrias quidem, ne tamen sacrifices, soli enim, & lunae dicatus est.

,

è chiaramente sancito da Pitagora che si può benissimo allevare un gallo, ma

che non va usato nei sacrifici, essendo sacro al sole e alla luna: Gallum

nutrias quidem, ne tamen sacrifices, soli enim, & lunae dicatus est.

Apriamo

una parentesi. Tra i precetti di Pitagora compare una massima che sembrerebbe

salvaguardare non solo il gallo dallo spiedo e dall'altare, ma qualunque

animale. Infatti un symbolum dice: Ab animalibus abstine. Ma è una

massima che mi fa pensare non allo spiedo, bensì alla zoofilia. O i

Pitagorici non mangiavano carne di animali (smentito dal fatto che il Maestro

diceva di non mangiare cuore e cervello, ovviamente degli animali –

Cor ne vores – Cerebrum ne edas), oppure i suoi discepoli dovevano astenersi

non dal mangiare qualsivoglia animale, bensì dal loro impiego sessuale, una

pratica adottata anche nel XXI secolo dai nostri pastori, e non solo.

D'accordo che Ficino ha usato abstine anche nel caso delle fave (A

fabis abstine) notoriamente sconsigliate a coloro che sono affetti da favismo![]() ,

ma negli altri casi in cui erano implicate frattaglie di animali ha usato i

verbi voro e edo.

,

ma negli altri casi in cui erano implicate frattaglie di animali ha usato i

verbi voro e edo.

E torniamo al gallo. Diogene Laerzio ci manda in confusione. Infatti nel riferire tutto quanto era noto circa il rapporto fra Pitagora e gli animali, non possiamo assolutamente sapere se concedesse di sacrificare e di mangiare i galli, bianchi o di qualunque colore fossero. Yonge suppone addirittura che il testo greco del capitolo XIX sia corrotto. Per cui è quasi inutile scervellarsi. Ecco i brani di Diogene Laerzio tradotti da Yonge, gli unici in cui fa la sua comparsa il gallo:

XVIII: He used to practise divination, as far as auguries and auspices go, but not by means of burnt offerings, except only the burning of frankincense. And all the sacrifices which he offered consisted of inanimate things. But some, however, assert that he did sacrifice animals, limiting himself to cocks, and sucking kids, which are called apalioi, but that he very rarely offered lambs. Aristoxenus, however, affirms that he permitted the eating of all other animals, and only abstained from oxen used in agriculture, and from rams.

XIX: He also forbade his disciples to eat white poultry, because a cock of that colour was sacred to Month, and was also a suppliant. He was also accounted a good animal; and he was sacred to the God Month, for he indicates the time. (Nota di Yonge: There is a great variety of suggestions as to the proper reading here. There is evidently some corruption in the text.)

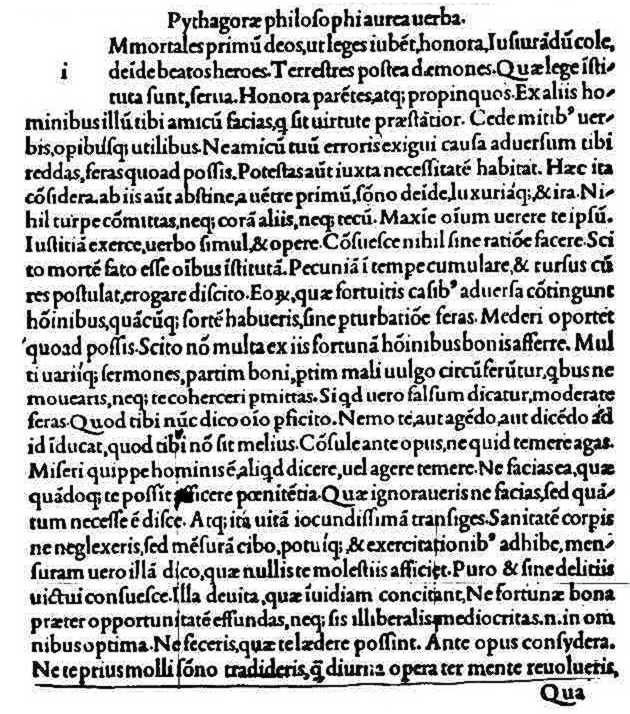

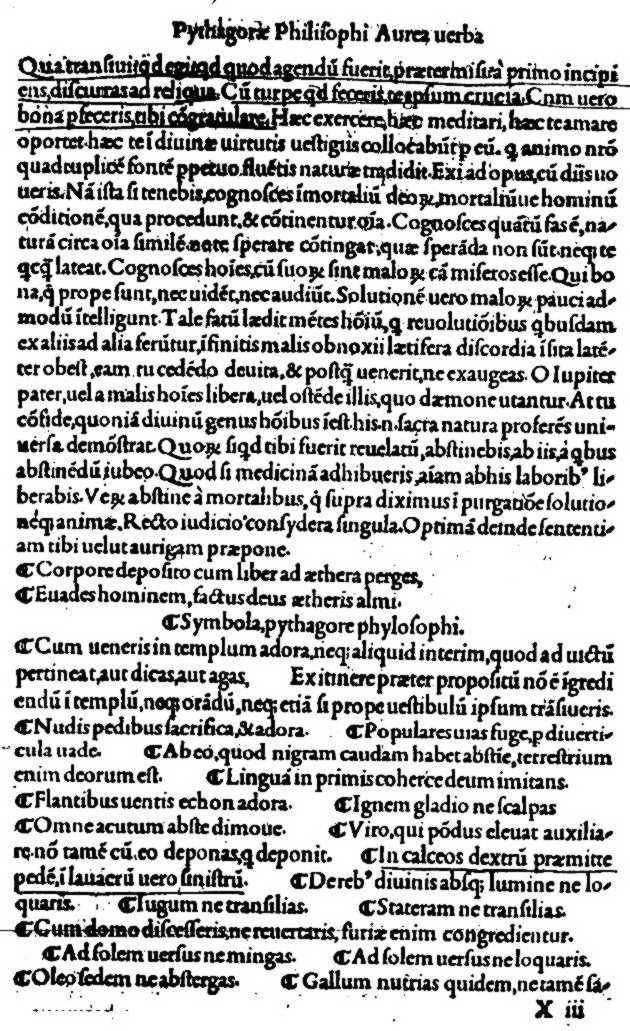

Pythagorae philosophi aurea verba

Symbola Pythagorae philosophi

pubblicati

da Aldo Manuzio![]() a Venezia nel 1497

a Venezia nel 1497

tradotti da Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499)

Diogenes

Laertius

The lives and opinions of eminent philosophers

Life of Pythagoras

translated

by C. D. Yonge

http://classicpersuasion.org/pw

|

I. SINCE

we have now gone through the Ionian philosophy, which was derived from

Thales, and the lives of the several illustrious men who were the

chief ornaments of that school; we will now proceed to treat of the

Italian School, which was founded by Pythagoras, the son of Mnesarchus,

a seal engraver, as he is recorded to have been by Hermippus; a native

of Samos, or as Aristoxenus asserts, a Tyrrhenian, and a native of one

of the islands which the Athenians occupied after they had driven out

the Tyrrhenians. But some authors say that he was the son of Marmacus,

the son of Hippasus, the son of Euthyphron, the son of Cleonymus, who

was an exile from Phlias; and that Marmacus settled in Samos, and that

from this circumstance Pythagoras was called a Samian. After that he

migrated to Lesbos, having come to Pherecydes with letters of

recommendation from Zoilus, his uncle. And having made three silver

goblets, he carried them to Egypt as a present for each of the three

priests. He had brothers, the eldest of whom was named Eunomus, the

middle one Tyrrhenus, and a slave named Zamolxis, to whom the Getae

sacrifice, believing him to be the same as Saturn, according to the

account of Herodotus (Herod. iv. 93.). II. He was

a pupil, as I have already mentioned, of Pherecydes, the Syrian; and

after his death he came to Samos, and became a pupil of Hermodamas,

the descendant of Creophylus, who was by this time an old man. III. And as

he was a young man, and devoted to learning, he quitted his country,

and got initiated into all the Grecian and barbarian sacred mysteries.

Accordingly, he went to Egypt, on which occasion Polycrates gave him a

letter of introduction to Amasis; and he learnt the Egyptian language,

as Antipho tells us, in his treatise on those men who have been

conspicuous for virtue, and he associated with the Chaldaeans and with

the Magi. IV.

Heraclides Ponticus says, that he was accustomed to speak of himself

in this manner; that he had formerly been Aethalides, and had been

accounted the son of Mercury; and that Mercury had desired him to

select any gift he pleased except immortality. And that he accordingly

had requested that whether living or dead, he might preserve the

memory of what had happened to him. While, therefore, he was alive, he

recollected everything; and when he was dead, he retained the same

memory. And at a subsequent period he passed into Euphorbus, and was

wounded by Menelaus. And while he was Euphorbus, he used to say that

he had formerly been Aethalides; and that he had received as a gift

from Mercury the perpetual transmigration of his soul, so that it was

constantly transmigrating and passing into whatever plants or animals

it pleased; and he had also received the gift of knowing and

recollecting all that his soul had suffered in hell, and what

sufferings too are endured by the rest of the souls. V. Now,

some people say that Pythagoras did not leave behind him a single

book; but they talk foolishly; for Heraclitus, the natural philosopher,

speaks plainly enough of him, saying, "Pythagoras, the Son of

Mnesarchus, was the most learned of all men in history; and having

selected from these writings, he thus formed his own wisdom and

extensive learning, and mischievous art." And he speaks thus,

because Pythagoras, in the beginning of his treatise on Natural

Philosophy, writes in the following manner: "By the air which I

breathe, and by the water which I drink, I will not endure to be

blamed on account of this discourse." Dear

youths, I warn you cherish peace divine, A third

about the Soul; a fourth on Piety; a fifth entitled Helothales, which

was the name of the father of Epicharmus, of Cos; a sixth called

Crotona, and other poems too. But the mystic discourse which is extant

under his name, they say is really the work of Hippasus, having been

composed with a view to bring Pythagoras into disrepute. There were

also many other books composed by Aston, of Crotona, and attributed to

Pythagoras. Aristoxenus

asserts that Pythagoras derived the greater part of his ethical

doctrines from Themistoclea, the priestess at Delphi. And Ion, of

Chios, in his Victories, says that he wrote some poems and attributed

them to Orpheus. They also say that the poem called the Scopeadae is

by him, which begins thus: Behave

not shamelessly to any one. VI.

And Sosicrates, in his Successions, relates that he, having being

asked by Leon, the tyrant of the Phliasians, who he was, replied,

"A philosopher." And adds, that he used to compare life to a

festival. "And as some people came to a festival to contend for

the prizes, and others for the purposes of traffic, and the best as

spectators; so also in life, the men of slavish dispositions,"

said he, "are born hunters after glory and covetousness, but

philosophers are seekers after truth." And thus he spoke on this

subject. But in the three treatises above mentioned, the following

principles are laid down by Pythagoras generally. VII.

And he divides the life of man thus. A boy for twenty years ; a young

man (neaniskos) for twenty years; a middle-aged man (neanias)

for twenty years; an old man for twenty years. And these different

ages correspond proportionably to the seasons: boyhood answers to

spring; youth to summer; middle age to autumn; and old age to winter.

And he uses neaniskos here as equivalent to meirakion

and neanias as equivalent to anêr. VIII.

He was the first person, as Timaeus says, who asserted that the

property of friends is common, and that friendship is equality. And

his disciples used to put all their possessions together into one

store, and use them in common; and for five years they kept silence,

doing nothing but listen to discourses, and never once seeing

Pythagoras, until they were approved; after that time they were

admitted into his house, and allowed to see him. They also abstained

from the use of cypress coffins, because the sceptre of Jupiter was

made of that wood, as Hermippus tells us in the second book of his

account of Pythagoras. IX.

He is said to have been a man of the most dignified appearance, and

his disciples adopted an opinion respecting him, that he was Apollo

who had come from the Hyperboreans; and it is said, that once when he

was stripped naked, he was seen to have a golden thigh. And there were

many people who affirmed, that when he was crossing the river Nessus

it addressed him by his name. X.

Timaeus, in the tenth book of his Histories, tells us, that he used to

say that women who were married to men had the names of the Gods,

being successively called virgins, then nymphs, and subsequently

mothers. XI.

It was Pythagoras also who carried geometry to perfection, after

Moeris had first found out the principles of the elements of that

science, as Aristiclides tells us in the second book of his History of

Alexander; and the part of the science to which Pythagoras applied

himself above all others was arithmetic. He also discovered the

numerical relation of sounds on a single string: he also studied

medicine. And Apollodorus, the logician, records of him, that he

sacrified a hecatomb, when he had discovered that the square of the

hypothenuse of a right-angled triangle is equal to the squares of the

sides containing the right angle. And there is an epigram which is

couched in the following terms: When

the great Samian sage his noble problem found, XII.

He is also said to have been the first man who trained athletes on

meat; and Eurymenes was the first man, according to the statement of

Favorinus, in the third book of his commentaries, who ever did submit

to this diet, as before that time men used to train themselves on dry

figs and moist cheese, and wheaten bread; as the same Favorinus infor

s us in the eighth book of his Universal History. But some authors

state that a trainer of the name of Pythagoras certainly did train his

athletes on this system, but that it was not our philosopher; for that

he even forbade men to kill animals at all, much less would have

allowed his disciples to eat then, as having a right to live in common

with mankind. And this was his pretext; but in reality, he prohibited

the eating of animals, because he wished to train and accustom men to

simplicity of life, so that all their food should be easily procurable,

as it would be, if they ate only such things as required no fire to

dress them, and if they drank plain water; for from this diet they

would derive health of body and acuteness of intellect. XIII.

He was also the first person who introduced measures and weights among

the Greeks; as Aristoxenus the musician informs us. XIV.

Parmenides, too, assures us, that he was the first person who asserted

the identity of Hesperus and Lucifer. XV.

And he was so greatly admired, that they used to say that his friends

looked on all his sayings as the oracles of God.2

And he himself says in his writings, that he had come among men after

having spent two hundred and seven years in the shades below.

Therefore the Lucanians and the Peucetians, and the Messapians, and

the Romans, flocked around him, coming with eagerness to hear his

discourses; but until the time of Philolaus, there were no doctrines

of Pythagoras ever divulged; and he was the first person who published

the three celebrated books which Plato wrote to have purchased for him

for a hundred minae. Nor were the number of his scholars who used to

come to him by night fewer than six hundred. And if any of them had

ever been permitted to see him, they wrote of it to their friends, as

if they had gained some great advantage. The

people of Metapontum used to call his house the temple of Ceres; and

the street leading to it they called the street of the Muses, as we

are told by Favorinus in his Universal History. Pythagoras,

too, formed many excellent men in Italy, by his precepts, and among

them Zaleucus,3

and Charondas,4

the lawgivers. XVI.

For he was very eminent for his power of attracting friendships; and

among other things, if ever he heard that any one had any community of

symbols with him, he at once made him a companion and a friend. XVII.

Now, what he called his symbols were such as these. "Do not stir

the fire with a sword." "Do not sit down on a bushel."

"Do not devour your heart." "Do not aid men in

discarding a burden, but in increasing one." "Always have

your bed packed up." "Do not bear the image of a God on a

ring." "Efface the traces of a pot in the ashes."

"Do not wipe a seat with a lamp." "Do not make water in

the sunshine." "Do not walk in the main street."

"Do not offer your right hand lightly." "Do not cherish

swallows under your roof." "Do not cherish birds with

crooked talons." "Do not defile; and do not stand upon the

parings of your nails or the cuttings of your hair." "Avoid

a sharp sword." "When you are travelling abroad, look not

back at your own borders." Now the precept not to stir fire with

a sword meant, not to provoke the anger or swelling pride of powerful

men; not to violate the beam of the balance meant, not to transgress

fairness and justice; not to sit on a bushel is to have an equal care

for the present and for the future, for by the bushel is meant one's

daily food. By not devouring one's heart, he intended to show that we

ought not to waste away our souls with grief and sorrow. In the

precept that a man when travelling abroad should not turn his eyes

back, he recommended those who were departing from life not to be

desirous to live, and not to be too much attracted by the pleasures

here on earth. And the other symbols may be explained in a similar

manner, that we may not be too prolix here. XVIII.

And above all things, he used to prohibit the eating of the erythinus,

and the melanurus; and also, he enjoined his disciples to abstain from

the hearts of animals, and from beans. And Aristotle informs us, that

he sometimes used also to add to these prohibitions paunches and

mullet. And some authors assert that he himself used to be contented

with honey and honeycomb, and bread, and that he never drank wine in

the day time. And his desert was usually vegetables, either boiled or

raw; and he very rarely ate fish. His dress was white, very clean, and

his bed-clothes were also white, and woollen, for linen had not yet

been introduced into that country. He was never known to have eaten

too much, or to have drunk too much, or to indulge in the pleasures of

love. He abstained wholly from laughter, and from all such indulgences

as jests and idle stories. And when he was angry, he never chastised

any one, whether slave or freeman. He used to call admonishing,

feeding storks. XIX.

The same author tells us, as I have already mentioned, that he

received his doctrines from Themistoclea, at Delphi. And Hieronymus

says, that when he descended to the shades below, he saw the soul of

Hesiod bound to a brazen pillar, and gnashing its teeth; and that of

Homer suspended from a tree, and snakes around it, as a punishment for

the things that they had said of the Gods. And that those people also

were punished who refrained from commerce with their wives; and that

on account of this he was greatly honoured by the people of Crotona. But

Aristippus, of Cyrene, in his Account of Natural Philosophers, says

that Pythagoras derived his name from the fact of his speaking (agoreuein)

truth no less than the God at Delphi (tou pythiou). In

what have I transgress'd? What have I done? And

that he used to forbid them to offer victims to the Gods, ordering

them to worship only at those altars which were unstained with blood.

He forbade them also to swear by the Gods; saying, "That every

man ought so to exercise himself, as to be worthy of belief without an

oath." He also taught men that it behoved them to honour their

elders, thinking that which was precedent in point of time more

honourable; just as in the world, the rising of the sun was more so

than the setting; in life, the beginning more so than the end; and in

animals, production more so than destruction. Another

of his rules was that men should honour the Gods above the daemones,

heroes above men; and of all men parents were entitled to the highest

degree of reverence. Another, that people should associate with one

another in such a way as not to make their friends enemies, but to

render their enemies friends. Another was that they should think

nothing exclusively their own. Another was to assist the law, and to

make war upon lawlessness. Not to destroy or injure a cultivated tree,

nor any animal either which does not injure men. That modesty and

decorum consisted in never yielding to laughter, and yet not looking

stern. He taught that men should avoid too much flesh, that they

should in travelling let rest and exertion alternate; that they should

exercise memory; that they should never say or do anything in anger;

that they should not pay respect to every kind of divination; that

they should use songs set to the lyre; and by hymns to the Gods and to

eminent men, display a reasonable gratitude to them. He also

forbade his disciples to eat beans, because, as they were flatulent,

they greatly partook of animal properties [he also said that men kept

their stomachs in better order by avoiding them]; and that such

abstinence made the visions which appear in one's sleep gentle and

free from agitation. Alexander also says, in his Successions of

Philosophers, that he found the following dogmas also set down in the

Commentaries of Pythagoras: That

the monad was the beginning of everything. From the monad proceeds an

indefinite duad, which is subordinate to the monad as to its cause.

That from the monad and the indefinite duad proceed numbers. And from

numbers signs. And from these last, lines of which plane figures

consist. And from plane figures are derived solid bodies. And from

solid bodies sensible bodies, of which last there are four elements;

fire, water, earth, and air. And that the world, which is endued with

life, and intellect, and which is of a spherical figure, having the

earth, which is also spherical, and inhabited all over in its centre,

results from a combination of these elements, and derives its motion

from them; and also that there are antipodes,5

and that what is below, as respects us, is above in respect of them. He also

taught that light and darkness, and cold and heat, and dryness and

moisture, were equally divided in the world; and that, while heat was

predominant it was summer; while cold had the mastery it was winter;

when dryness prevailed it was spring; and when moisture preponderated,

winter. And while all these qualities were on a level, then was the

loveliest season of the year; of which the flourishing spring was the

wholesome period, and the season of autumn the most pernicious one. Of

the day, he said that the flourishing period was the morning, and the

fading one the evening; on which account that also was the least

healthy time. Another

of his theories was, that the air around the earth was immoveable, and

pregnant with disease; and that everything in it was mortal; but that

the upper air was in perpetual motion, and pure and salubrious; and

that everything in that was immortal, and on that account divine. And

that the sun, and the moon, and the stars, were all Gods; for in them

the warm principle predominates which is the cause of life. And that

the moon derives its light from the sun. And that there is a

relationship between men and the Gods, because men partake of the

divine principle; on which account also, God exercises his providence

for our advantage. Also, that fate is the cause of the arrangement of

the world both generally and particularly. Moreover, that a ray from

the sun penetrated both the cold aether and the dense aether; and they

call the air (aêr) the cold aether (psychron aithera),

and the sea and moisture they call the dense aether (pachun

aethera). And this ray descends into the depths, and in this way

vivifies everything. And everything which partakes of the principle of

heat lives, on which account also plants are animated beings; but that

all living things have not necessarily souls. And that the soul is a

something torn off from the aether, both warm and cold, from its

partaking of the cold aether. And that the soul is something different

from life. Also, that it is immortal, because that from which it has

been detached is immortal. Also,

that animals are born from one another by seeds, and that it is

impossible for there to be any spontaneous production by the earth.

And that seed is a drop from the brain which contains in itself a warm

vapour; and that when this is applied to the womb, it transmits virtue,

and moisture, and blood from the brain, from which flesh, and sinews,

and bones, and hair, and the whole body are produced. And from the

vapour is produced the soul, and also sensation. And that the infant

first becomes a solid body at the end of forty days; but, according to

the principles of harmony, it is not perfect till seven, or perhaps

nine, or at most ten months, and then it is brought forth. And that it

contains in itself all the principles of life, which are all connected

together, and by their union and combination form a harmonious whole,

each of them, developing itself at the appointed time. The

senses in general, and especially the sight, are a vapour of excessive

warmth, and on this account a man is said to see through air, and

through water. For the hot principle is opposed by the cold one; since,

if the vapour in the eyes were cold, it would have the same

temperature as the air, and so would be dissipated. As it is, in some

passages he calls the eyes the gates of the sun. And he speaks in a

similar manner of hearing, and of the other senses. He also

says that the soul of man is divided into three parts; into intuition

(nous), and reason (phren) and mind (thymos),

and that the first and last divisions are found also in other animals,

but that the middle one, reason, is only found in man. And that the

chief abode of the soul is in those parts of the body which are

between the heart and the brain. And that that portion of it which is

in the heart is the mind (thymos); but that deliberation (nous),

and reason (phren), reside in the brain:

(6) Moreover,

that the senses are drops from them; and that the reasoning sense is

immortal, but the others are mortal. And that the soul is nourished by

the blood; and that reasons are the winds of the soul. That it is

invisible, and so are its reasons, since the aether itself is

invisible. That the links of the soul are the veins, and the arteries

and the nerves. But that when it is vigorous, and is by itself in a

quiescent state, then its links are words and actions. That when it is

cast forth upon the earth it wanders about, resembling the body.

Moreover, that Mercury is the steward of the souls, and that on this

account he has the name of Conductor, and Commercial, and Infernal,

since it is he who conducts the souls from their bodies, and from

earth, and sea; and that he conducts the pure souls to the highest

region, and that he does not allow the impure ones to approach them,

nor to come near one another; but commits them to be bound in

indissoluble fetters by the Furies. The Pythagoreans also assert, that

the whole air is full of souls, and that these are those which are

accounted daemones, and heroes. Also, that it is by them that dreams

are sent among men, and also the tokens of disease and health; these

last too, being sent not only to men, but to sheep also and other

cattle. Also, that it is they who are concerned with purifications,

and expiations, and all kinds of divination, and oracular predictions,

and things of that kind. They

also say, that the most important privilege in man is the being able

to persuade his soul to either good or bad. And that men are happy

when they have a good soul; yet, that they are never quiet, and that

they never retain the same mind long. Also, that an oath is justice;

and that on that account, Jupiter is called Jupiter of Oaths (Orkios).

Also, that virtue is harmony, and health, and universal good, and God;

on which account everything owes its existence and consistency to

harmony. Also, that friendship is a harmonious equality. Again,

they teach that one ought not to pay equal honours to Gods and to

heroes; but that one ought to honour the Gods at all times, extolling

them with praises, clothed in white garments, and keeping one's body

chaste; but that one ought not to pay such honour to the heroes till

after midday. Also, that a state of purity is brought about by

purifications, and washings, and sprinklings, and by a man's purifying

himself from all funerals, or concubinage, or pollution of every kind,

and by abstaining from all flesh that has either been killed or died

of itself, and from mullets, and from melanuri, and from eggs, and

from such animals as lay eggs, and from beans, and from other things

which are prohibited by those who have the charge of the mysteries in

the temples. And

Aristotle says, in his treatise on Beans, that Pythagoras enjoined his

disciples to abstain from beans, either because they resemble some

part of the human body, or because they are like the gates of hell (for

they are the only plants without parts); or because they dry up other

plants, or because they are representatives of universal nature, or

because they are used in elections in oligarchical governments. He

also forbade his disciples to pick up what fell from the table, for

the sake of accustoming them not to eat immoderately, or else because

such things belong to the dead. But

Aristophanes says, that what falls belongs to the heroes; saying, in

his Heroes: Never

taste the things which fall He also

forbade his disciples to eat white poultry, because a cock of

that colour was sacred to Month, and was also a suppliant. He was also

accounted a good animal;7

and he was sacred to the God Month, for he indicates the time. The

Pythagoreans were also forbidden to eat of all fish that were sacred;

on the ground that the same animals ought not to be served up before

both Gods and men just as the same things do not belong to freemen and

to slaves. Now, white is an indication of a good nature, and black of

a bad one. Another of the precepts of Pythagoras was, that men ought

not to break bread; because in ancient times friends used to assemble

around one loaf, as they even now do among the barbarians. Nor would

he allow men to divide bread which unites them. Some think that he

laid down this rule in reference to the judgment which takes place in

hell; some because this practice engenders timidity in war. According

to others, what is alluded to is the Union, which presides over the

government of the universe. Another

of his doctrines was, that of all solid figures the sphere was the

most beautiful; and of all plane figures, the circle. That old age and

all diminution were similar, and also increase and youth were

identical. That health was the permanence of form, and disease the

destruction of it. Of salt his opinion was, that it ought to be set

before people as a reminder of justice; for salt preserves everything

which it touches, and it is composed of the purest particles of water

and sea. These

are the doctrines which Alexander asserts that he discovered in the

Pythagorean treatises; and Aristotle gives a similar account of them. XX.

Timon, in his Silli, has not left unnoticed the dignified

appearance of Pythagoras, when he attacks him on other points. And his

words are these: Pythagoras,

who often teaches And

respecting his having been different people at different times,

Xenophanes adds his evidence in an elegiac poem which commences thus: Now

I will on another subject touch, And the

passage in which he mentions Pythagoras is as follows ; They

say that once as passing by he saw These

are the words of Xenophanes. Cratinus

also ridiculed him in his Pythagorean Woman; but in his Tarentines, he

speaks thus: They

are accustomed, if by chance they see And

Innesimachus says in his Alcmaeon: As

we do sacrifice to the Phoebus whom Austophon

says in his Pythagorean: A.

He said that when he did descend below And

again, in the same play he says: They

eat XXI.

Pythagoras died in this manner. When he was sitting with some of his

companions in Milo's house, some one of those whom he did not think

worthy of admission into it, was excited by envy to set fire to it.

But some say that the people of Crotona themselves did this, being

afraid lest he might aspire to the tyranny. And that Pythagoras was

caught as he was trying to escape; and coming to a place full of beans,

he stopped there, saying that it was better to be caught than to

trample on the beans, and better to be slain than to speak; and so he

was murdered by those who were pursuing him. And in this way, also,

most of his companions were slain; being in number about forty; but

that a very few did escape, among whom were Archippus, of Tarentum,

and Lysis, whom I have mentioned before. But

Dicaearchus relates that Pythagoras died afterwards, having escaped as

far as the temple of the Muses, at Metapontum, and that he died there

of starvation, having abstained from food for forty days. And

Heraclides says, in his abridgment of the life of Satyrus, that after

he had buried Pherecydes in Delos, he returned to Italy, and finding

there a superb banquet prepared at the house of Milo, of Cortona, he

left Crotona, and went to Metapontum, and there put an end to his life

by starvation, not wishing to live any longer. But Hermippus says,

that when there was war between the people of Agrigentum and the

Syracusans, Pythagoras went out with his usual companions, and took

the part of the Agrigentines; and as they were put to flight, he ran

all round a field of beans, instead of crossing it, and so was slain

by the Syracusans; and that the rest, being about five-and-thirty in

number, were burnt at Tarentum, when they were trying to excite a

sedition in the state against the principal magistrates. Hermippus also relates another story about Pythagoras. For he says that when he was in Italy, he made a subterraneous apartment, and charged his mother to write an account of everything that took place, marking the time of each on a tablet, and then to send them down to him, until he came up again; and that his mother did so; and that Pythagoras came up again after a certain time, lean, and reduced to a skeleton; and that he came into the public assembly, and said that he had arrived from the shades below, and then he recited to them all that had happened during his absence. And they, being charmed by what he told them, wept and lamented, and believed that Pythagoras was a divine being; so that they even entrusted their wives to him, as likely to learn some good from him; and that they too were called Pythagoreans. And this is the story of Hermippus. XXII.

And Pythagoras had a wife, whose name was Theano; the daughter of

Brontinus, of Crotona. But some say that she was the wife of Brontinus,

and only a pupil of Pythagoras. And he had a daughter named Damo, as

Lysis mentions in his letter to Hipparchus; where he speaks thus of

Pythagoras: "And many say that you philosophize in public, as

Pythagoras also used to do; who, when he had entrusted his

Commentaries to Damo, his daughter, charged her to divulge them to no

person out of the house. And she, though she might have sold his

discourses for much money, would not abandon them, for she thought

poverty and obedience to her father's injunctions more valuable than

gold; and that too, though she was a woman." He had

also a son, named Telauges, who was the successor of his father in his

school, and who, according to some authors, was the teacher of

Empedocles. At least Hippobotus relates that Empedocles said "Telauges,

noble youth, whom in due time, But

there is no book extant, which is the work of Telauges, though there

are some extant, which are attributed to his mother Theano. And they

tell a story of her, that once, when she was asked how long a woman

ought to be absent from her husband to be pure, she said, the moment

she leaves her own husband, she is pure; but she is never pure at all,

after she leaves any one else. And she recommended a woman, who was

going to her husband, to put off her modesty with her clothes, and

when she left him, to resume it again with her clothes; and when she

was asked, "What clothes?" she said, "Those which cause

you to be called a woman." XXIII.

Now Pythagoras, as Heraclides, the son of Sarapian, relates, died when

he was eighty years of age; according to his own account of his age,

but according to the common account, he was more than ninety. And we

have written a sportive epigram on him, which is couched in the

following terms: You're

not the only man who has abstained And

another, which runs thus: Pythagoras

was so wise a man, that he And

another, as follows: Should

you Phythagoras' doctrine wish to know, And

this one too: Alas!

alas! why did Pythagoras hold XXIV.

And he flourished about the sixtieth Olympiad and his system lasted

for nine or ten generations. And the last of the Pythagoreans, whom

Aristoxenus knew, were Xenophilus, the Chalcidean, from Thrace; and

Phanton, the Phliasian, and Echurates, and Diodes, and Polymnestus,

who were also Phliasians, and they were disciples of Philolaus and

Eurytus, of Tarentum. XXV.

And there were four men of the name of Pythagoras, about the same

time, at no great distance from one another. One was a native of

Crotona, a man who attained tyrannical power; the second was a

Phliasian, a trainer of wrestlers, as some say; the third was a native

of Zacynthus; the fourth was this our philosopher, to whom they say

the mysteries of philosophy belong, in whose time that proverbial

phrase, "Ipse dixit," was introduced into ordinary

life. Some also affirm, that there was another man of the name of

Pythagoras, a statuary of Rhodes; who is believed to have been the

first discoverer of rhythm and proportion; and another was a Samian

statuary; and another an orator, of no reputation; and another was a

physician, who wrote a treatise on Squills; and also some essays on

Homer; and another was a man, who wrote a history of the affairs of

the Dorians, as we are told by Dionysius. But

Eratosthenes says, as Favorinus quotes him, in the eighth book of his

Universal History, that this philosopher, of whom we are speaking, was

the first man who ever practised boxing in a scientific manner, in the

forty-eighth Olympiad, having his hair long, and being clothed in a

purple robe; and that he was rejected from the competition among boys,

and being ridiculed for his application, he immediately entered among

the men, and came off victorious. And this statement is confirmed

among other things, by the epigram which Theaetetus composed: Stranger,

if e'er you knew Pythagoras, Favorinus

says, that he employed definitions, on account of the mathematical

subjects to which he applied himself. And that Socrates and those who

were his pupils, did so still more; and that they were subsequently

followed in this by Aristotle and the Stoics. He too,

was the first person, who ever gave the name of kosmos to the

universe, and the first who called the earth round; though

Theophrastus attributes this to Parmenides, and Zeno to Hesiod. They

say too, that Cylon used to be a constant adversary of his, as

Antidicus was of Socrates. And this epigram also used to be repeated,

concerning Pythagoras the athlete: Pythagoras

of Samos, son of Crates, XXVI.

There is a letter of this philosopher extant, which is couched in the

following terms: PYTHAGORAS

TO ANAXIMENES.

"You

too, my most excellent friend, if you were not superior to Pythagoras,

in birth and reputation, would have migrated from Miletus and gone

elsewhere. But now the reputation of your father keeps you back, which

perhaps would have restrained me too, if I had been like Anaximenes.

But if you, who are the most eminent man, abandon the cities, all

their ornaments will be taken from them; and the Median power will be

more dangerous to them. Nor is it always seasonable to be studying

astronomy, but it is more honourable to exhibit a regard for one's

country. And I myself am not always occupied about speculations of my

own fancy, but I am busied also with the wars which the Italians are

waging against one another." But

since we have now finished our account of Pythagoras, we must also

speak of the most eminent of the Pythagoreans. After whom, we must

mention those who are spoken of more promiscuously in connection with

no particular school; and then we will connect the whole series of

philosophers worth speaking of, till we arrive at Epicurus, as we have

already promised. Now

Jelanges and Theano we have mentioned; and we must now speak of

Empedocles, in the first place, for, according to some accounts, he

was a pupil of Pythagoras. Footnotes 1. This

resembles the account which Ovid puts into the mouth of Pythagoras, in

the last book of his Metamorphoses, where he makes him say: Morte

carent animae, semperque priore relicta Which

may be translated: Death

has no pow'r th' immortal soul to slay; 2. This

passage has been interpreted in more ways than one. Casaubon thinks

with great probability that there is a hiatus in the text. I have

endeavoured to extract a meaning out of what remains. Compare Samuel

ii. 16, 23. "And the counsel of Ahitophel, which he counselled in

those days, was as if a man had enquired at the oracle of God; so was

all the counsel of Ahitophel both with David and with Absalum." 3.

Zaleucus was the celebrated lawgiver of the Epizephyrian Locrians, and

is said to have been originally a slave employed by a shepherd, and to

have been set free and appointed lawgiver by the direction of an

oracle, in consequence of his announcing some excellent laws, which he

represented Minerva as having communicated to him in a dream. Diogenes,

is wrong however, in calling him a disciple of Pythagoras (see Bentley

on Phalaris), as he lived about a hundred years before his time; his

true date being 660 B.C. The code of Zaleucus is stated to have been

the first collection of written laws that the Greeks possessed. Their

character was that of great severity. They have not come down to us.

His death is said to have occurred thus. Among his laws was one

forbidding any citizen to enter the senate house in arms, under the

penalty of death. But in a sudden emergency, Zaleucus himself, in a

moment of forgetfulness, transgressed his own law: on which he slew

himself, declaring that he would vindicate his law. (Eustath. ad. Il.

i. p. 60). Diodorus, however, tells the same story of Charondas. 4.

Charondas was a lawgiver of Catana, who legislated for his own city

and the other towns of Challidian origin in Magna Grecia, such as

Zancle, Naxos, Leontini, Eubaea, Mylae, Himera, Callipolis, and

Rhegium. His laws have not been preserved to us, with the exception of

a few judgments. They were probably in verse, for Athenaeus says that

they were sung in Athens at banquets. Aristotle tells us that they

were adapted to an aristocracy. It is much doubted whether it is

really true that he was a disciple of Pythagoras, though we are not

sure of his exact time, so that we cannot pronounce it as impossible

as in the preceding case. He must have lived before the time of

Anaxilaus, tyrant of Rhegium, who reigned from B.C. 494 to B.C. 476,

because he abolished the laws of Charondas, which had previously been

in force in that city. Diodorus gives a code of laws which he states

that Charondas gave to the city of Thurii, which was not founded till

B.C. 443, when he must certainly have been dead a long time. There is

one law of his preserved by Stobaeus, which is probably authentic,

since it is found in a fragment of Theophrastus; enacting that all

buying and selling shall be transacted by ready money only. 5. This

doctrine is alluded to doubtfully by Virgil, Georg. i. 247. Illic,

ut perhibent, aut intempesta silet nox Thus

translated by Dryden, 1. 338: There,

as they say, perpetual night is found, 6. nous

appears in a division like this to be the deliberative part of the

mind; phren, the rational part of the intellect: thymos,

that part with which the passions are concerned. 7. There

is a great variety of suggestions as to the proper reading here. There

is evidently some corruption in the text. |

Scanned and edited for Peithô's Web from The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, by Diogenes Laertius, Literally translated by C.D. Yonge. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1853. Footnotes have been converted to endnotes. Some, but not all, of Yonge's spellings of ancient names have been updated.

All of the materials at Peithô's Web are provided for your enjoyment, as is, without any warranty of any kind or for any purpose.

Dictionnaire

historique

de la médecine ancienne et moderne

par Nicolas François Joseph Eloy

Mons – 1778