Lessico

Cimbri

Le migrazioni dei Cimbri e dei Teutoni con vittorie e sconfitte

Antica

popolazione di stirpe germanica. Dalle sedi originarie sulla destra dell'Elba

(Jylland o Jütland, Holstein e Schleswig), alla fine del sec. II aC mossero

contro i Teutoni verso il centro e il sud della Germania, ma, risospinti dai

Boi![]() ,

penetrarono lungo la valle del Danubio sconfiggendo nel 113 il console romano

Papirio Carbone.

,

penetrarono lungo la valle del Danubio sconfiggendo nel 113 il console romano

Papirio Carbone.

Entrarono

poi in Gallia, rafforzati da gruppi di Elvezi, e sconfissero diversi eserciti

romani. Fu Gaio Mario![]() a stroncarne per sempre la furia aggressiva con le memorabili sconfitte che

inflisse nel 102 ai Teutoni ad Aquae Sextiae (odierna Aix-en-Provence)

e ai Cimbri nel 101 ai Campi Raudii, presso Vercelli.

a stroncarne per sempre la furia aggressiva con le memorabili sconfitte che

inflisse nel 102 ai Teutoni ad Aquae Sextiae (odierna Aix-en-Provence)

e ai Cimbri nel 101 ai Campi Raudii, presso Vercelli.

Festo![]() in De

verborum significatione così dice dei Cimbri:

in De

verborum significatione così dice dei Cimbri:

Cimbri lingua

Gallica latrones dicuntur.

Cimbri

I Cimbri erano una tribù germanica che assieme ai Teutoni e agli Ambroni invasero il territorio della repubblica romana alla fine del II secolo aC. Le fonti antiche individuano la loro origine nel nord delle Jutland.

Origine e nome

Secondo le fonti greche e romane i Cimbri provenivano dallo Jutland, che era

chiamato Chersonesus Cimbrica dal loro nome. Secondo le Res gestae

(c. 26) di Augusto![]() , i Cimbri erano ancora presenti nella penisola danese

intorno all'anno 1.

, i Cimbri erano ancora presenti nella penisola danese

intorno all'anno 1.

« Classis mea per Oceanum ab ostio Rheni ad solis orientis regionem usque ad fines Cimbrorum navigavit, quo neque terra neque mari quisquam Romanus ante ide tempus adit, Cimbrique et Charydes et Semnones et eiusdem tractus alii Germanorum populi per legatos amicitiam meam et populi Romani petierunt.»

« La mia flotta ha navigato attraverso l'oceano, dalle bocche del Reno verso la regione del sole nascente fino alle terre dei Cimbri, presso i quali nessun Romano era andato in precedenza né per mare né per terra, e i Cimbri, i Carudi, i Semnoni e altri popoli Germanici della stessa regione, con i loro ambasciatori chiesero l'amicizia mia e del popolo romano.»

Augusto - Res gestae

Lo storico greco Strabone![]() testimonia che i Cimbri erano ancora presenti tra

le tribù Germaniche, probabilmente nella "Cimbrica peninsula" (Geogr.

7.2.1):

testimonia che i Cimbri erano ancora presenti tra

le tribù Germaniche, probabilmente nella "Cimbrica peninsula" (Geogr.

7.2.1):

« Per quanto riguarda i Cimbri, delle cose che sono state dette su di loro alcune sono sbagliate e altre estremamente improbabili. Innanzitutto si potrebbe mettere in dubbio il fatto che siano diventati dei pirati nomadi a causa di un'inondazione che avrebbe distrutto le loro dimore nella loro penisola natia [Jütland], infatti possiedono ancora le terre ove un tempo originariamente vivevano; e hanno inviato come dono ad Augusto il calderone più sacro del loro paese, come offerta della loro amicizia e come richiesta del perdono delle loro colpe precedenti e quando la loro richiesta fu accettata alzarono le vele per tornare a casa ed è ridicolo supporre che si siano allontanati dalle loro case perché messi in agitazione da un fenomeno che è naturale e che si verifica due volte ogni giorno. E l'affermazione che una volta ci sia stata una marea straordinaria sembra una montatura, perché se l'Oceano si comporta in questo modo con aumenti e diminuzioni, tuttavia sono regolati e periodici. »

Sulle mappe di Tolomeo![]() , i "Kimbroi" sono collocati nella parte più

a nord delle penisola dello Jutland, cioè l'attuale Himmerland (giacché il

Vendsyssel-Thy era in quel periodo un gruppo di isole). Himmerland (Old Danish

Himbersysel) in genere è considerato che riporti il loro nome, in una forma

più arcaica, senza la Legge di Grimm (PIE k > Germ. h). In alterna il

Latin C- rappresenta un tentativo di rendere il non familiare proto-germanico

[χ], forse da parte di interpreti di lingua celtica

(intermediari celtici spiegherebbero anche il germ. *Þeuðanoz che divenne il

latino Teutones).

, i "Kimbroi" sono collocati nella parte più

a nord delle penisola dello Jutland, cioè l'attuale Himmerland (giacché il

Vendsyssel-Thy era in quel periodo un gruppo di isole). Himmerland (Old Danish

Himbersysel) in genere è considerato che riporti il loro nome, in una forma

più arcaica, senza la Legge di Grimm (PIE k > Germ. h). In alterna il

Latin C- rappresenta un tentativo di rendere il non familiare proto-germanico

[χ], forse da parte di interpreti di lingua celtica

(intermediari celtici spiegherebbero anche il germ. *Þeuðanoz che divenne il

latino Teutones).

L'origine del nome non è conosciuta. Un'etimologia possibile è PIE "abitante", "casa" (> ing. home), a sua volta una derivazione da "live"; e quindi il germanico *χimbra- trova un esatto legame con lo slavico "fattore" (> croato, serbo sebar, russ. sjabër).

A causa della somiglianza dei nomi i Cimbri sono spesso associati con i Cymry, il nome con cui i Gallesi chiamano se stessi. Tuttavia questa parola è generalmente fatta derivare dal celtico *Kombroges, nel significato di Compatrioti, ed è difficile pensare che i Romani abbiano registrato questa forma come Cimbri (la forma Cambri è neo-latino). Il nome dei Cimbri è stato anche posto in relazione con la parola kimme nel significato di "bordo", cioè il popolo della costa, ma questa ipotesi è incompatibile con l'associazione di Cimbri con Himmerland giacché kimme non mostra gli effetti della legge di Grimm. Ed infine dall'antichità il nome era stato accostato a quello dei Cimmeri.

Lingua dei Cimbri

Uno dei problemi maggiori è che in questo periodo Greci e Romani tendono a indicare tutti popoli a Nord della loro sfera d'influenza come Galli, Celti o Germani piuttosto indiscriminatamente. Cesare sembra esser stato uno dei primi autori a distinguere fra i due gruppi e aveva un motivo politico per farlo: era un argomento a favore del confine renano. Tuttavia non ci si può fidare completamente di Cesare e Tacito quando ascrivono individui e tribù all'una o all'altra categoria.

Se i Cimbri avessero risieduto nello Jutland settentrionale si potrebbe

dedurre che la loro lingua fosse Proto-Germanica. Al contrario vi sono

indicazioni che portano a pensare che i Cimbri parlassero di fatto una lingua

del ceppo celtico. Infatti, riferendosi all'Oceano del Nord (il Mar Baltico o

il Mare del Nord), Plinio il Vecchio![]() (circa 77 dC) scrive:

(circa 77 dC) scrive:

« Philemon Morimarusam a Cimbris vocari, hoc est mortuum mare, inde usque ad promunturium Rusbeas, ultra deinde Cronium. »

« Filemone disse che è chiamato Morimarusa, cioè Mare Morto, fino al promontorio di Rubea e dopo quello di Cronio.»

Plinio il Vecchio - Naturalis Historia 4.95

Le parole per "mare" e "morto" sono muir e marbh in Irlandese e mor e marw in Gallese. La stessa parola per "mare è conosciuta anche nel germanico, ma con una a (*mari-), in quanto l'altra parola è sconosciuta in tutti i dialetti della Germania. Ancora, dato che Plinio non ha avuto la parola direttamente da un informatore cimbro, non si può affermare che quella parola sia in effetti Gallica ed è comunque possibile che il Mare del Nord o il Mar Baltico fossero considerati "morti" e "gelidi" dai Centro-Europei piuttosto che dagli Scandinavi, stanziati sulle coste del mare.

Markale (1976) scrisse che i Cimbri furono associati agli Helvetii, e più specialmente con gli indiscutibili celti Tiguri. Come si vedrà più avanti, queste associazioni potrebbero condurre a una discendenza comune, richiamata da 200 anni prima. Inoltre, tutti i capitribù Cimbri conosciuti hanno nomi celtici, compreso Boiorix (re dei Boii), Gaesorix (re dei Gaesatae, mercenari celtici alpini), e Lugius (in onore della divinità celtica Lugh). Hubert (1934) afferma:"Tutti questi nomi sono celtici, non potrebbero essere altro." (Cap. IV, I) Fornisce molte informazioni riguardo questa questione ed altri aspetti rilevanti grazie a un approccio chiaro e oggettivo.

A ogni modo, alcuni autori hanno prospettive differenti,:per esempio Wells (1995) afferma - senza alcuna prova - che i Cimbri, originari della Danimarca (la penisola Cimbra) non sono sicuramente Celti, in quanto i loro nomi vengono trasmessi attraverso scrittori classici in forme celtiche. Il calderone di Gundestrup, scoperto in una torbiera nel territorio Cimbro, è un testamento della vita celtica in ogni dettaglio, incluse sanguinarie cerimonie che coinvolgevano direttamente sacerdotesse, che prendevano luogo sopra un grande calderone.

Posidonius, un antico storico dei Cimbri, 22 anni al tempo della loro affermazione nel mondo (113 aC), rende una descrizione verbale identica ai dettagli visuali sul calderone. I Cimbri veneravano anche il calderone stesso (ai tempi di Augusto usavano chiamarlo "il loro tesoro più prezioso"), il quale, in accordo con quanto detto sopra, indicherebbe una cultura e un comportamento tipici della cultura celtica e non germanica. Appiano di Alessandria, che scrisse il suo "Storia di Roma: Le Guerre Galliche" nel 130 aC parla di "Galli", "Celti" e "Germani". Riguardo i Cimbri afferma che erano un enorme clan composto da tribù celtiche guerriere, ai tempi in cui Cesare combatté i Germani.

Altre prove della lingua del Cimbri sono circostanziali: a noi viene detto che i Romani arruolarono i Galli Celti per comportarsi come spie nei villaggi Cimbri, in modo da favorire la vittoria finale dell'armata romana nel 101 aC. Questa è una prova a supporto della teoria che vuole i Cimbri come Celti piuttosto che Germani. In modo simile, i re dei Cimbri e dei Teutoni portavano nomi in tutto e per tutto celtici (vedi Boiorix e Teutobodus). Dall'altra parte, l'origine di un nome non è necessariamente correlata con la provenienza della persona che lo porta e la sua appartenenza etnica. Non c'è comunque nulla che provi la correlazione dei nomi portati dai Cimbri con i nomi germanici. L'etimologia di cui sopra (PIE *t?im-ro-) sarebbe da considerare valida solamente in un contesto celtico (e nella forma latina sarebbe più facile da spiegare). Inoltre, le documentazioni romane categorizzano i Cimbri come una tribù germanica (Cesare, BG 1.33.3-4; Plinio, NH 4.100; Tacito, Germ. 37, Hist. 4.73). Inoltre, tutte le documentazioni classiche confermano unanimemente la patria dei Cimbri nello Jutland, e non c'è nessuna prova di una popolazione di lingua celtica nel sud della Scandinavia (i linguisti considerano lo Jutland una regione linguistica della Germania). Come si può quindi vedere, la "teoria germanica" si basa comunque su delle prove attendibili. Ad ogni modo, la teoria offre le seguenti possibilità:

I Cimbri erano una popolazione di lingua germanica, e le informazioni riguardanti i nomi e le parole dateci dagli antichi autori sono inaccurate.

I Cimbri erano orginariamente di lingua germanica, ma, avendo assorbito una quantità enorme di individui di lingua celtica durante il loro lungo viaggio dall'Europa Centrale all'Europa Occidentale, adottarono la lingua celtica.

I Cimbri erano di lingua germanica, ma a causa dell'importanza della cultura celtica, l'élite delle tribù germaniche era bilingue (vedi parole celtiche adottate come *rikaz "nobile", *ambahtaz "servo").

I Cimbri parlavano una lingua celtica già nel loro paese d'origine, il Nord dello Jutland.

I Cimbri erano una tribù celtica originaria dell'Europa Centrale, e avevano solamente il nome in comune con i Cimbri dello Jutland.

I Cimbri attuali

Sui rilievi tra Veneto (Lessinia, Altopiano di Asiago, Cansiglio) e Trentino è presente una ristrettissima minoranza che parla la lingua cimbra, un idioma appartenente al ceppo delle lingue germaniche. Una leggenda, forse improbabile, afferma che queste popolazioni siano discendenti dagli antichi Cimbri che, dopo la sconfitta dei Campi Raudii si sarebbero infine rifugiati sulle Alpi.

Per alcuni quelle popolazioni che oggi vengono chiamate Cimbri discendono invece da un gruppo di bavaresi che a quanto pare emigrò sul versante opposto delle Alpi dove le signorie locali avevano bisogno della loro abilità di taglialegna. La discendenza non è certa in quanto lo stesso cimbro si discosta dai dialetti collegati all'area austro-bavarese (come lo sono invece gli altri dialetti tedeschi parlati nell'Italia settentrionale), è più vicino in realtà a quello sassone. Rapporti di parentela sembrano invece esserci tra le popolazioni dello Jutland e gli abitanti della Gran Bretagna settentrionale.

Cimbri

Tipologia linguistica Il termine "cimbro" è una italianizzazione della parola "zimbar" con cui gli abitanti della zona chiamano la propria lingua, un dialetto bavarese arcaico, più propriamente chiamato baiuvaro e definito dai linguisti come "la più antica parlata periferica esistente del dominio linguistico tedesco". Nonostante l'omonimia, non vi sono correlazioni tra le popolazioni di epoca romana conosciute come Cimbri e provenienti dall'attuale Danimarca e sconfitte nel 101 aC dall'esercito del console romano Gaio Mario ai Campi Raudi.

Diffusione in Italia La lingua baiuvara è presente nella regione del Trentino e più precisamente a Luserna, nei centri di Gallio, Rotzo, Roana sull'Altopiano di Asiago e a Giazza. Nonostante l'area geografica piuttosto ampia, la lingua cimbra si è mantenuta solo a Lucerna, mentre è virtualmente estinta nelle altre zone dell'Altipiano e delle province di Verona e Vicenza. Luserna, piccolo paese a circa 40 km da Trento è l'ultima isola linguistica in cui il cimbro viene parlato da quasi tutta la popolazione.

Origine storica I primi insediamenti di lingua baiuvara sull'Altopiano di Asiago, sulle colline veronesi e in Trentino risalgono all'XI- XII secolo, quando gruppi di coloni bavaresi lasciarono le terre del Convento dei Benediktbeuern in Baviera per sfuggire alle carestie. Qui diedero vita in breve tempo a forme più evolute di autogoverno, come le Magnifiche Comunità dei Sette Comuni Vicentini e dei Tredici Comuni Veronesi sui Monti Lessini. Nonostante l'omonimia, non vi sono correlazioni tra le popolazioni di epoca romana conosciute come Cimbri e provenienti dall'attuale Danimarca e sconfitte nel 101 aC dall'esercito del console romano Gaio Mario ai Campi Raudi.

Popolazione La comunità di lingua baiuvara è composta da circa 2230

persone, di cui 862 residenti nella Provincia di Trento (ultimo censimento del

2001).

Status: La lingua cimbra è riconosciuta come lingua minoritaria dello stato

italiano ed è compresa dalle norme di tutela e promozione delle lingue

minoritarie del Trentino Alto Adige.

Uso pubblico Il cimbro non è usato come lingua dell'amministrazione

pubblica, mentre è sostenuto l'uso di denominazioni bilingui per la

toponomastica locale.

Scuola: Il cimbro non è insegnato a scuola ufficialmente. Si segnalano

singole iniziative di insegnanti che tengono lezioni in lingua cimbra, fuori

dal normale orario scolastico.

Media Da aprile 2006 l'emittente televisiva regionale TCA trasmette ogni settimana un telegiornale in cimbro "Zimbar Earde" e uno in mòcheno "Sim to en Bersntol" che vanno in onda dopo il telegiornale in lingua italiana. Il programma è trasmesso in tutto il Trentino e Alto Adige. Tutti i servizi sono in cimbro e mòcheno con sottotitoli in italiano. Ogni primo e terzo venerdì del mese, il quotidiano "Trentino" pubblica una pagina in cimbro "Di sait vo Lusèrn".

www.eurac.edu

The migrations of the Teutons and the Cimbri

The Cimbri were a Celtic or Germanic tribe who together with the Teutones and the Ambrones threatened the Roman Republic in the late 2nd century BC. The ancient sources located their home of origin in Jutland, which was referred to as the Cimbrian peninsula throughout antiquity (Greek: Kimbrike Chersonesos).

Homeland and name

Archaeologists have not found any clear indications of a mass migration from Jutland in the early Iron Age. The Gundestrup Cauldron, which was deposited in a bog in Himmerland in the 2nd or 1st century BC, shows that there was some sort of contact with southeastern Europe, but it is uncertain if this contact can be associated with the Cimbrian expedition. Advocates for a northern homeland point to Greek and Roman sources that associate the Cimbri with the peninsula of Jutland. According to the Res gestae (ch. 26) of Augustus, the Cimbri were still found in the area around the turn of the Common Era:

“ My fleet sailed from the mouth of the Rhine eastward as far as the lands of the Cimbri, to which, up to that time, no Roman had ever penetrated either by land or by sea, and the Cimbri and Charydes and Semnones and other peoples of the Germans of that same region through their envoys sought my friendship and that of the Roman people. ”

The contemporary Greek geographer Strabo testifies that the Cimbri still existed as a Germanic tribe, presumably in the "Cimbric peninsula" (since they are said to live by the North Sea and to have paid tribute to Augustus):

“ As for the Cimbri, some things that are told about them are incorrect and others are extremely improbable. For instance, one could not accept such a reason for their having become a wandering and piratical folk as this that while they were dwelling on a Peninsula they were driven out of their habitations by a great flood-tide; for in fact they still hold the country which they held in earlier times; and they sent as a present to Augustus the most sacred kettle in their country, with a plea for his friendship and for an amnesty of their earlier offences, and when their petition was granted they set sail for home; and it is ridiculous to suppose that they departed from their homes because they were incensed on account of a phenomenon that is natural and eternal, occurring twice every day. And the assertion that an excessive flood-tide once occurred looks like a fabrication, for when the ocean is affected in this way it is subject to increases and diminutions, but these are regulated and periodical.”

On the map of Ptolemy, the "Kimbroi" are placed on the northernmost part of the peninsula of Jutland, i.e. in the modern landscape of Himmerland south of Limfjorden (since Vendsyssel-Thy north of the fjord was at that time a group of islands). Himmerland (Old Danish Himbersysel) is generally thought to preserve their name, in an older form without Grimm's law (PIE k > Germ. h). Alternatively, Latin C- represents an attempt to render the unfamiliar Proto-Germanic h = [χ], perhaps due to Celtic-speaking interpreters (a Celtic intermediary would also explain why Germanic *Þeuðanoz became Latin Teutones).

The origin of the name Cimbri is unknown. One etymology is PIE *t?im-ro- "inhabitant", from t?oi-m- "home" (> Eng. home), itself a derivation from "live"; then, the Germanic *?imbra- finds an exact cognate in Slavic sebr? "farmer" (> Croatian, Serbian sebar, Russ. sjabër).

Because of the similarity of the names, the Cimbri are often associated with Cymry, the Welsh name for themselves. However, this word is generally derived from Celtic *Kombroges, meaning compatriots, and it is hardly conceivable that the Romans would have recorded such a form as Cimbri. The name has also been related to the word kimme meaning "rim", i.e. the people of the coast, but this is incompatible with the association of Cimbri to Himmerland since kimme does not exhibit the effects of Grimm's law. Finally, since Antiquity, the name has been related to that of the Cimmerians.

Language of the Cimbri

A major problem in determining whether the Cimbri were speaking a Celtic or a Germanic language is that at this time the Greeks and Romans tended to refer to all groups to the north of their sphere of influence as Gauls, Celts, or Germani rather indiscriminately. Caesar seems to be one of the first authors to distinguish the two groups, and he has a political motive for doing that (it is an argument in favour of the Rhine border). Yet, one cannot always trust Caesar and Tacitus when they ascribe individuals and tribes to one or the other category. Most ancient sources categorize the Cimbri as a Germanic tribe, but some ancient authors include the Cimbri among the Celts.

There are few direct testimonies to the language of the Cimbri: Referring to the Northern Ocean (the Baltic or the North Sea), Pliny the Elder states: "Philemon says that it is called Morimarusa, i.e. the Dead Sea, by the Cimbri, until the promontory of Rubea, and after that Cronium." The words for "sea" and "dead" are muir and marbh in Irish and mor and marw in Welsh. The same word for "sea" is also known from Germanic, but with an a (*mari-), whereas a cognate of marbh is unknown in all dialects of Germanic. Yet, given that Pliny had not had the word directly from a Cimbric informant, it cannot be ruled out that the word is in fact Gaulish instead.

Similarly, the kings of the Cimbri and Teutones carry what look like Celtic names, viz. Boiorix and Teutobodus, but the origin of a name need not say anything about the ethnicity or language of the individual carrying the name. On the other hand, there is no positive evidence of Germanic words or names in connection with the Cimbri. The etymology given above (PIE *t?im-ro-) would work just as well in a Celtic context (and the Latin form with c rather than h would be easier to explain). Other evidence to the language of the Cimbri is circumstantial: thus, we are told that the Romans enlisted Gaulish Celts to act as spies in the Cimbri camp prior to the final showdown with the Roman army in 101 BC. This is evidence in support of "the Celtic rather than the German theory".

Jean Markale wrote that the Cimbri were associated with the Helvetii, and more especially with the indisputably Celtic Tiguri. As will be seen later, these associations may link to a common ancestry, recalled from two hundred years previous. Also, all the known Cimbri chiefs had Celtic names, including Boiorix (King of the Boii), Gaesorix (King of the Gaesatae, who were Alpine Celtic mercenaries), and Lugius (after the Celtic god Lugh). Henri Hubert states "All these names are Celtic, and they cannot be anything else". Some authors take a different perspective. For example, Peter S. Wells states that the Cimbri "are certainly not Celts", without providing argumentation.

Moving south-east

Some time before 100 BC many of the Cimbri, as well as the Teutones and Ambrones migrated south-east. After several unsuccessful battles with the Boii and other Celtic tribes, they appeared ca 113 BC in Noricum, where they invaded the lands of one of Rome's allies, the Taurisci. On the request of the Roman consul Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, sent to defend the Taurisci, they retreated, only to find themselves deceived and attacked at the Battle of Noreia, where they defeated the Romans. Only a storm, which separated the combatants, saved the Roman forces from complete annihilation.

Invading Gaul

Now the road to Italy was open, but they turned west towards Gaul. They came into frequent conflict with the Romans, who usually came out the losers. In 109 BC, they defeated a Roman army under the consul Marcus Junius Silanus, who was the commander of Gallia Narbonensis. The same year, they defeated another Roman army under the consul Gaius Cassius Longinus, who was killed at Burdigala (modern day Bordeaux). In 107 BC, the Romans once again lost against the Tigurines, who were allies of the Cimbri.

Attacking the Roman Republic

It was not until 105 BC that they planned an attack on the Roman Republic itself. At the Rhône, the Cimbri clashed with the Roman armies. The Roman commanders, the proconsul Quintus Servilius Caepio and the consul Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, hindered Roman coordination and so the Cimbri succeeded in first defeating the legate Marcus Aurelius Scaurus and later cause a devastating defeat on Caepio and Maximus at the Battle of Arausio. The Romans lost as many as 80,000 men, excluding auxiliary cavalry and non-combatants who brought the total loss closer to 112,000. Rome was in panic, and the terror cimbricus became proverbial. Everyone expected to soon see the new Gauls outside of the gates of Rome. Desperate measures were taken: contrary to the Roman constitution, Gaius Marius, who had defeated Jugurtha, was elected consul and supreme commander for five years in a row (104-100 BC).

Defeat

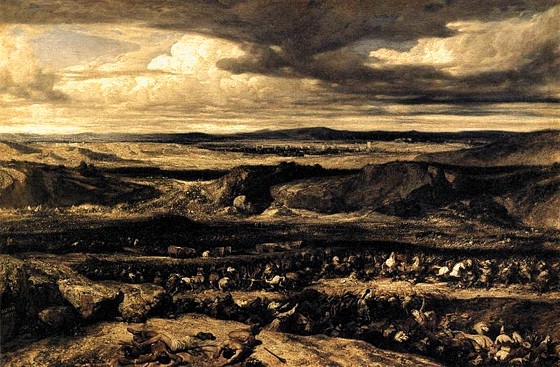

The Defeat of the Cimbri

by Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803-1860)

In 103 BC, the Cimbri and their proto-Germanic allies, the Teutons, had turned to Spain where they pillaged far and wide. During this time C. Marius had the time to prepare and, in 102 BC, he was ready to meet the Teutons and the Ambrones at the Rhône. These two tribes intended to pass into Italy through the western passes, while the Cimbri and the Tigurines were to take the northern route across the Rhine and later across the Tyrolian Alps.

At the estuary of the Isère River, the Teutons and the Ambrones met Marius, whose well-defended camp they did not manage to overrun. Instead, they pursued their route, and Marius followed them. At Aquae Sextiae, the Romans won two battles and took the Teuton king Teutobod prisoner.

The Cimbri had penetrated through the Alps into northern Italy, The consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus had not dared to fortify the passes, but instead he had retreated behind the River Po, and so the land was open to the invaders. The Cimbri did not hurry, and the victors of Aquae Sextiae had the time to arrive with reinforcements. At the Battle of Vercellae, at the confluence of the Sesia River with the Po River, in 101 BC, the long voyage of the Cimbri also came to an end.

It was a devastating defeat and both the chieftains Lugius and Boiorix died. The women killed both themselves and their children in order to avoid slavery. The Cimbri were annihilated, although some may have survived to return to the homeland where a population with this name was residing in northern Jutland in the 1st century AD, according to the sources quoted above.

Culture

Strabo gives this vivid description of the Cimbric folklore (Geogr. 7.2.3, trans. H.L. Jones): “ Their wives, who would accompany them on their expeditions, were attended by priestesses who were seers; these were grey-haired, clad in white, with flaxen cloaks fastened on with clasps, girt with girdles of bronze, and bare-footed; now sword in hand these priestesses would meet with the prisoners of war throughout the camp, and having first crowned them with wreaths would lead them to a brazen vessel of about twenty amphorae; and they had a raised platform which the priestess would mount, and then, bending over the kettle, would cut the throat of each prisoner after he had been lifted up; and from the blood that poured forth into the vessel some of the priestesses would draw a prophecy, while still others would split open the body and from an inspection of the entrails would utter a prophecy of victory for their own people; and during the battles they would beat on the hides that were stretched over the wicker-bodies of the wagons and in this way produce an unearthly noise. ”

The Cimbri are depicted as ferocious warriors who did not fear death. The host

was followed by women and children on carts. Aged women dressed in white (cf.

the Old Norse völva) sacrificed the prisoners of war and sprinkled their

blood (cf. the Old Norse blót), the nature of which allowed them to see what

was to come.

If the Cimbri did in fact come from Jutland, evidence that the they practised

ritualistic sacrifice may be found in the Haraldskær Woman discovered in

Jutland in the year 1835. Noosemarks and skin piercing were evident and she

had been thrown into a bog rather than buried or cremated. Furthermore, the

Gundestrup cauldron, found in Himmerland, may be a sacrificial vessel like the

one described in Strabo's text. The work itself was of Thracian origin.

Descendants

According to Caesar, the Belgian tribe of the Atuatuci "was descended from the Cimbri and Teutoni, who, upon their march into our province and Italy, set down such of their stock and stuff as they could not drive or carry with them on the near (i.e. west) side of the Rhine, and left six thousand men of their company therewith as guard and garrison" (Gall. 2.29, trans. Edwards). They founded the city of Atuatuca in the land of the Belgic Eburones, whom they dominated. Thus Ambiorix king of the Eburones paid tribute and gave his son and nephew as hostages to the Atuatuci (Gall. 6.27). In the first century AD, the Eburones were replaced or absorbed by the Germanic Tungri, and the city was known as Atuatuca Tungrorum, i.e. the modern city of Tongeren.

The population of modern-day Himmerland claims to be the heirs of the ancient Cimbri. The adventures of the Cimbri are described by the Danish nobel-prize-winning author, Johannes V. Jensen, himself born in Himmerland, in the novel Cimbrernes Tog (1922), included in the epic cycle Den lange Rejse (English The Long Journey, 1923). The so-called Cimbrian bull ("Cimbrertyren"), a sculpture by Anders Bundgaard, was erected 14 April 1937 on a central town square in Aalborg, the capital of the region of North Jutland.

In northern Italy, a Germanic language traditionally called Cimbrian is spoken in some villages near the cities of Verona and Vicenza. Since the fourteenth century, it was believed that the speakers were the direct descendants of the Cimbrians defeated at Vercelli, some hundred kilometers to the west. However, this is most certainly not true. The "Cimbriano" language is in fact related to the Austro-Bavarian dialects of German like many other Upper German dialects in northern Italy, it is only more isolated and therefore less recognizable as German. The name was either indigenous (from Zimmer = "timber"?) or given to them by Italian humanists who wanted to find this "living fossil" of antiquity.