Lessico

Charles

de L’Écluse

Carolus Clusius

incisione

di Theodor de Bry (1528-1598)

da Bibliotheca chalcographica di Jean-Jacques Boissard - 1669

Medico e botanico francese noto anche come Carolus

Clusius (Arras 1526 - Leida 1609). Studiò le flore di Austria, Ungheria, Belgio

e Spagna e descrisse circa 4000 piante, slegandole da ogni vincolo con la

medicina e l'agricoltura, contrariamente alla consuetudine delle opere

botaniche dell'epoca. Gli fu dedicata la Primula clusiana![]() e il genere Clusia.

e il genere Clusia.

Nella traduzione in latino fatta da L’Ècluse delle Observationes di Pierre Belon![]() (1589), Carolus

Clusius compare con l’aggettivo Atrebas, cioè l'Atrebate, in quanto la

sua città natale, Arras, prima dell'era cristiana con il nome di Nementacum

era capoluogo della tribù celtica degli Atrebati.

(1589), Carolus

Clusius compare con l’aggettivo Atrebas, cioè l'Atrebate, in quanto la

sua città natale, Arras, prima dell'era cristiana con il nome di Nementacum

era capoluogo della tribù celtica degli Atrebati.

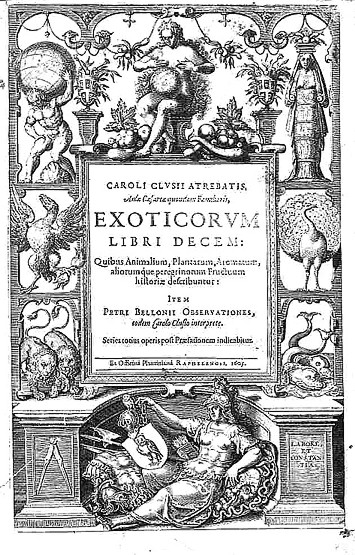

Una delle sue opere più famose – il cui frontespizio reca pure Caroli Clusii Atrebatis - è rappresentata da Exoticorum libri decem (1605). L’Écluse è il nome francese della città olandese di Sluis (in Zelanda, presso il confine belga) e sluis in olandese significa chiusa, così come dam significa diga.

GLOSSAIRE

DE BOTANIQUE OU DICTIONNAIRE ETYMOLOGIQUE

de tous les noms et termes relatifs à

cette science.

Par Alexandre de Théis

Paris - chez Gabriel Dufour et compagnie, Rue des Mathurins – St. Jacques, n.o 7 – 1810

Pagina 120

|

Entre les nombreuses victimes qu’a faites la passion de la botanique, on doit donner la première place à de l’ Écluse. Il entreprit de la façon la plus pénible les Voyages de Portugal, Espagne, Angleterre, Allemagne, Hongrie, etc. et dès l’âge de vingt-quatre ans il fut attaqué d’une hydropisie causée par l’excès de fatigue. Le célèbre Rondelet le guérit par l’usage de la chicorée. À trente neuf ans, il se cassa le bras droit en herborisant; peu après la cuisse droite. A cinquante-cinq ans il se démit le pied gauche à Vienne, et huit ans après la hanche droite. Ayant été mal traité, il ne marcha plus qu’avec des béquilles. Le défaut d’exercice lui donna des obstructions; il eut la pierre, un hernie, etc. Après avoir dirigé, pendant quatorze ans, le Jardin impérial de Vienne, il retourna dans la Belgique sa patrie. Nommé professeur de botanique à Leyde, il y donna des leçons pendant seize ans, et il mourut enfin accablé de tous les maux. |

Tra le numerose vittime dovute alla passione della botanica, si deve attribuire il primo posto a de L’Écluse. Egli intraprese nella maniera più faticosa i viaggi in Portogallo, Spagna, Inghilterra, Germania, Ungheria etc. e a partire dall'età di 24 anni fu colpito da un anasarca causato dall'eccesso di fatica. Il celebre Guillaume Rondelet lo guarì con l'uso della cicoria. A 39 anni erborizzando - andando in cerca di erbe per uso medicinale o a scopo di studio - si ruppe il braccio destro e poco dopo la coscia destra. A 55 anni a Vienna si slogò il piede sinistro e 8 anni dopo l'anca destra. Essendo stato curato male, camminò usando solo delle stampelle. La scarsa attività fisica gli regalò delle ostruzioni: ebbe la calcolosi, un'ernia etc. Dopo aver diretto per 14 anni il Giardino Imperiale di Vienna, fece ritorno in Belgio, la sua patria. Nominato professore di Botanica a Leida, vi diede delle lezioni per 16 anni e infine morì prostrato da tutti quanti i mali. |

Exoticorum libri decem (Ten books of exotic life forms) is an illustrated zoological and botanical compendium in Latin, published at Leiden in 1605 by Charles de l'Écluse. On the title page the author's name appears in its well-known Latin form Carolus Clusius. The full title is: Exoticorum libri decem, quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum, aliorumque peregrinorum fructuum historiae describuntur (Ten books of exotica: the history and uses of animals, plants, aromatics and other natural products from distant lands). Clusius was not only an original biologist but also a remarkable linguist. He became well known as a translator and editor of the works of others. Exoticorum libri decem consists partly of his own discoveries, partly of translated and edited versions of earlier publications, always properly acknowledged, and with many new illustrations. Separately identifiable within this compendium can be found Clusius's Latin translations, with his own notes, from:

Garcia de Orta, Colóquios dos simples e drogas he cousas medicinais da Índia (1563)

Nicolás Monardes, Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales (1565-1574)

Cristóvão da Costa, Tractado de las drogas y medicinas de las Indias orientales (1578)

There

is also material by Prospero Alpini![]() (Prosper

Alpinus) with notes by Clusius. As a separately paginated appendix appears

Clusius's Latin translation (first published in 1589) of Pierre Belon, Observations

(1553).

(Prosper

Alpinus) with notes by Clusius. As a separately paginated appendix appears

Clusius's Latin translation (first published in 1589) of Pierre Belon, Observations

(1553).

Carolus Clusius, or by his French name Charles de l’Escluse, was born in Arras (Province of Artois, Northern France) on 19 February, 1526. His father Michel de l’Escluse, Seigneur de Watènes, was a nobleman who served as councillor at the provincial court of Artois. Charles went to university at Louvain, where he studied law under Gabriel Mudaeus. In 1546 he entered the Collegium Trilingue in Louvain. One year later, in 1548, he was at Marburg to study law, but his protestant conviction appears to have led him to Wittenburg in 1549 where he studied with the reformer Melanchthon.

On the advice of Melanchthon

he changed his subject to medicine and botany. In 1551 he was at Montpellier,

studying with the botanical professor Guillaume Rondelet![]() . During these

formative years he acquired no less than eight languages and an extensive

knowledge of a wide variety of subjects. His first publication was a French

translation of Rembert Dodoens’

. During these

formative years he acquired no less than eight languages and an extensive

knowledge of a wide variety of subjects. His first publication was a French

translation of Rembert Dodoens’![]() herbal, published in Antwerp in 1557. Having

finished his studies, he worked in various places and occupations, for

instance as tutor and travel companion to the sons of Antoine Fugger, Count of

Kirchperg and Weissenhorn.

herbal, published in Antwerp in 1557. Having

finished his studies, he worked in various places and occupations, for

instance as tutor and travel companion to the sons of Antoine Fugger, Count of

Kirchperg and Weissenhorn.

In the 1560s he was back in the Southern Netherlands, enjoying the protection of such influential patrons as Gui and Marc Lauweryn in Bruges. During this period his also was involved in the production of the splendid series of ‘libri picturati’. After short stays in Paris and London, he was invited to Vienna by Emperor Maximilian II in 1573 as court physician and overseer of the imperial garden.

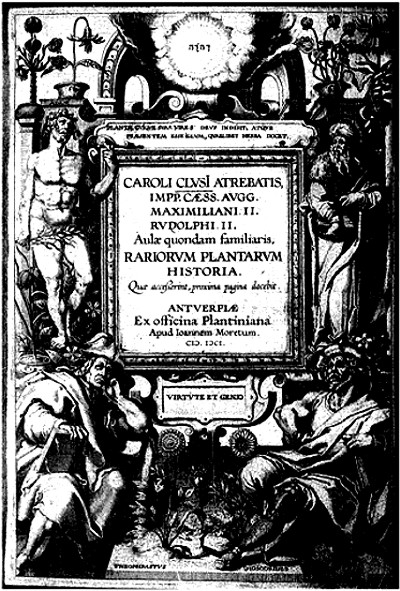

1601

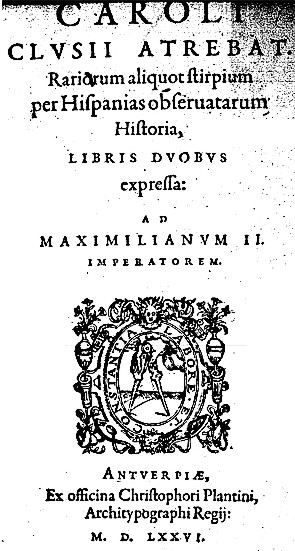

This high patronage enabled him to travel all over Europe, collecting information for his botanical studies and introducing a range of new plants from outside Europe, such as the tulip and the potato. In 1576 his Spanish flora (Rariorum aliquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia) was published by Christopher Plantin at Antwerp, followed in 1583 by his description of the plants of Austria and neighbouring regions (Rariorum aliquot stirpium, per Pannoniam, Austriam, & vicinas quasdam provincias observatarum historia).

By then, religious conflict had forced his departure to Frankfurt, where he

worked for the publishing firm of De Bry. In 1593 Clusius was finally

appointed honorary professor of botany at the University of Leiden in 1593, a

chair which he occupied until his death. The Officina Plantiniana published

his collected works in two impressive volumes between 1601 and 1605. Another

important achievement was the foundation of the Leiden botanical gardens, the

second such institution north of the Alps. Clusius died on the 4th

of April 1609 and was buried in the Vrouwekerk in Leiden, next to his equally

renowned colleague Josephus Justus Scaliger![]() .

.

http://athena.leidenuniv.nl

Charles de l'Écluse

Nymphaea from Rariorum plantarum historia (1601)

Charles de l'Écluse, L'Escluse, or Carolus Clusius (Arras, February 19, 1526 – Leiden April 4, 1609), seigneur de Watènes, was the Flemish doctor and pioneering botanist, perhaps the most influential of all 16th century scientific horticulturists.

He studied at Montpellier with the famous medical professor Guillaume Rondelet, though he never practiced medicine. In 1573 he was appointed prefect of the imperial medical garden in Vienna by Maximilian II and made Gentleman of the Imperial Chamber, but he was discharged from the imperial court shortly after the accession of Rudolf II in 1576. After leaving Vienna in the late 1580s he established himself in Frankfurt am Main, before his appointment as professor at the University of Leiden in 1593. He helped create one of the earliest formal botanical garden of Europe at Leyden, the Hortus Academicus, and his detailed planting lists have made it possible to recreate his garden near where it originally lay.

In the history of gardening he is remembered not only for his scholarship but also for his observations on tulips "breaking" — a phenomenon discovered in the late 19th century to be due to a virus — causing the many different flamed and feathered varieties, which led to the speculative tulip mania of the 1630s. Clusius laid the foundations of Dutch tulip breeding and the bulb industry today.

His first publication was a French translation of Rembert Dodoens's herbal, published in Antwerp in 1557 by van der Loë. His Antidotarium sive de exacta componendorum miscendorumque medicamentorum ratione ll. III ... nunc ex Ital. sermone Latini facti (1561) initiated his fruitful collaboration with the renowned Plantin printing press at Antwerp, which permitted him to issue late-breaking discoveries in natural history and to ornament his texts with elaborate engravings.

Clusius, as he was known to his contemporaries, published two major original works: his Rariorum aliquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia (1576) — is one of the earliest books on Spanish flora — and his Rariorum stirpium per Pannonias observatorum Historiae (1583) is the first book on Austrian and Hungarian alpine flora. His collected works were published in two parts: Rariorum plantarum historia (1601) contains his Spanish and Austrian flora and adds more information about new plants as well as a pioneering mycological study on mushrooms from Central Europe; and Exoticorum libri decem (1605) is an important survey of exotic flora and fauna, both still often consulted. He contributed as well to Abraham Ortelius's map of Spain. Clusius translated several contemporary works in natural science.

Clusius

was also among the first to study the flora of Austria, under the auspices of

Emperor Maximilian II. He was the first botanist to climb the Ötscher and the

Schneeberg in Lower Austria, which was also the first documented ascent of the

latter. His contribution to the study of alpine plants has led to many of them

being named in his honour, such as Gentiana clusii, Potentilla

clusiana and Primula clusiana![]() . The

genus Clusia (whence the family Clusiaceae) also honours Clusius.

The standard author abbreviation Clus. is used to indicate this individual as

the author when citing a botanical name.

. The

genus Clusia (whence the family Clusiaceae) also honours Clusius.

The standard author abbreviation Clus. is used to indicate this individual as

the author when citing a botanical name.

Works by Charles de l'Écluse

1557: Rembert Dodoens, Histoire des plantes: French translation from Dutch

1567: Garcia de Orta, Aromatum et simplicium aliquot medicamentorum apud Indios nascentium historia: Latin translation from Portuguese

1574: Nicolás Monardes, De simplicibus medicamentis ex occidentali India delatis quorum in medicina usus est: Latin translation from Spanish

1579: Revised edition under the title Simplicium medicamentorum ex novo orbe delatorum, quorum in medicina usus est, historia

1576: Rariorum aliquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia

1582: Compendium of the translations from Garcia de Orta and Nicolás Monardes, now combined with selections from Cristóvão da Costa, Tractado de las drogas y medicinas de las Indias orientales

1593: Further revised edition of this compendium

1583: Rariorum stirpium per Pannonias observatorum Historiae

1601: Rariorum plantarum historia

1605: Exoticorum libri decem, including final revised editions of the translations from Garcia de Orta, Nicolás Monardes and Cristóvão da Costa

Translations of his work

1589: Dell'historia dei semplici aromati et altre cose che vengono portare dall'Indie Orientali pertinente all'uso della medicina ... di Don Garzia dall'Horto. Italian re-translation by Annibale Briganti of Clusius's edited translations of Garcia de Orta and Nicolás Monardes.

Jules Charles de L'Écluse (ou de L'Escluse), Carolus Clusius sous sa forme latine, né le 19 février 1526 à Arras et mort le 4 avril 1609 à Leyde, est un médecin et un botaniste français réfugié en Flandre (Belgique), l'un des plus fameux du XVIe siècle. Il est le créateur de l'un des premiers jardins botaniques d'Europe à Leyde, et peut être considéré comme le premier mycologue au monde et le fondateur de l'horticulture. Il est également le premier à fournir des descriptions réellement scientifiques des végétaux.

Il entame ses études de droit à Gand puis à l'université de Louvain. En 1548, il part pour Marbourg, avant d'aller à Wittenburg suivre l'enseignement de Melanchthon en 1549. Sur les conseils de celui-ci, il abandonne le droit pour l'étude de la médecine et de la botanique. En 1551, il étudie la botanique à Montpellier sous la direction du célèbre médecin Guillaume Rondelet (1507-1566), qui l'héberge chez lui durant trois ans, en qualité de secrétaire.

En 1557, il traduit en français l'herbier de Rembert Dodoens (1517-1585): Histoire des plantes. Ses études achevées, Charles de L'Écluse occupe des fonctions variées. En 1573, l'empereur Maximilien II (1527-1576) le nomme médecin de cour et responsable du jardin impérial. Grâce à cette protection, il peut voyager dans toute l'Europe, rassemble de nombreuses observations et réunit de nombreux spécimens de végétaux, certains venus de contrées lointaines comme la tulipe (qu'il introduit aux Pays-Bas) et la pomme de terre. À la mort de son protecteur, il doit quitter Vienne après y avoir passé quatorze années.

En 1576, de L'Écluse fait paraître une flore d'Espagne (Rariorum aliquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia) suivi en 1583 de la description des plantes d'Autriche et des régions voisines (Rariorum aliquot stirpium, per Pannoniam, Austriam, & vicinas quasdam provincias observatarum historia). En 1587, il fonde le jardin botanique (hortus botanicus), différent du jardin médicinal (hortus medicus), à l'université de Leyde. Il y cultive des plantes rares venant d'Europe du sud, d'Espagne, du Portugal, de Hongrie. À cette même université, il obtient le poste de professeur de botanique (1593) qu'il occupera jusqu'à sa mort.

De L'Écluse publie un important traité de botanique et de mycologie, Rariorum plantarum historia: Fungorum in Pannoniis observatorum brevis historia (1601), illustré par plus de mille gravures et où il tente de regrouper les espèces par affinités. Ses observations sont remarquablement précises. Il est, sans doute, le premier botaniste à établir des diagnoses véritablement scientifiques. Il décrit, pour la première fois de nombreuses espèces comme le marronnier (qu'il introduit en Hollande), le jasmin et l'aralia. Cet ouvrage constitue en outre la première grande monographie mycologique et la première flore régionale de champignons. Clusius y donne la description de 105 espèces de champignons de Hongrie, dont 45 comestibles.

En 1605,

il fait paraître Exoticorum libri decem où il souhaite décrire

toutes les espèces exotiques, animales ou végétales, qu'il peut obtenir.

Vivant à Leyde, il occupe une place de choix pour obtenir, des vaisseaux qui

arrivent aux Pays-Bas, des spécimens. Son livre décrit de nombreuses espèces

nouvelles: le casoar (du genre Casuarius), le manchot de Magellan (Spheniscus

magellanicus), le perroquet maillé (Deroptyus accipitrinus), le

lori noir (Lorius garrulus), l'ibis rouge (Eudocimus ruber) et

bien d'autres. Il décrit aussi le grand pingouin (Pinguinus impennis)

dont il reçoit, en 1604, un spécimen avec d'autres espèces, d'Henrik Højer

qui explore les îles Féroé. Le botaniste Charles Plumier![]() (1646-1704) lui a dédié le genre Clusia de la famille des Clusiaceae.

(1646-1704) lui a dédié le genre Clusia de la famille des Clusiaceae.

Primula clusiana L. 1753 est une petite vivace formant une rosette. Elle appartient à la famille des primulacées. Très rustique, elle est originaire d'Autriche.

Feuilles persistantes de 4 à 8 cm de long, oblongues à ovales, coriaces, vert foncé.

Floraison au printemps. Ombelles solitaires ou groupées, de deux à quatre fleurs de 2 à 4 cm de diamètre, aplaties, de couleur rosée à lilas avec un œil blanc.

Taille 10 cm de haut pour 15 cm de diamètre.