Lessico

Carbonchio dei cereali

Il nome ustilago

è un vocabolo latino che indicava un’erba, forse il cardus silvaticus.

Il carbone, detto anche carbonchio, è una malattia che colpisce in prevalenza

piante di cereali, ma anche altre specie (cipolla, aglio, ecc.) sia coltivate

sia allo stato selvatico. Deve il suo nome al colore nerastro delle formazioni

polverulente che si accumulano nei tessuti dei soggetti colpiti e che sono

costituite dalle clamidospore di diversi generi di Funghi Basidiomiceti![]() , detti

funghi del carbone o più brevemente carboni, appartenenti alla famiglia

Ustilaginacee. Clamidospora è la spora duratura costituita da una cellula contenente sostanze di riserva e dotata di membrana fortemente ispessita: è atta ad assicurare la sopravvivenza di varie specie fungine in condizioni sfavorevoli alla vita vegetativa.

, detti

funghi del carbone o più brevemente carboni, appartenenti alla famiglia

Ustilaginacee. Clamidospora è la spora duratura costituita da una cellula contenente sostanze di riserva e dotata di membrana fortemente ispessita: è atta ad assicurare la sopravvivenza di varie specie fungine in condizioni sfavorevoli alla vita vegetativa.

Lo sviluppo del micelio di questi funghi provoca deformazioni che possono essere diffuse per tutto l'organismo dell'ospite oppure limitate ai punti nei quali si concentrano i sori di clamidospore (soro deriva dal greco sorós che significa mucchio, una conformazione a gruppo di sporangi, di organi contenenti spore).

Il luogo e il momento dell'infezione variano a seconda della specie parassita, per cui si possono distinguere tre tipi principali di questa malattia, che sono particolarmente noti perché interessano alcune fra le più importanti Graminacee coltivate. Nel primo l'agente infettivo si introduce nell'organismo vegetale anche quando questo ha già raggiunto un certo grado di sviluppo e si diffonde nei suoi tessuti meristematici (embrionali) provocando escrescenze più o meno voluminose in una parte qualsiasi della pianta. Ne è un esempio il carbone del granoturco, Ustilago maydis.

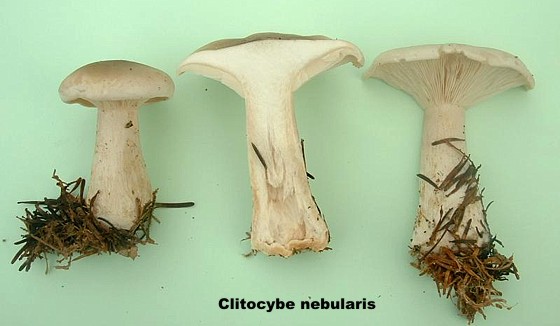

Nel secondo tipo il contagio è

intraseminale: il micelio del fungo si introduce negli ovari al tempo della

fioritura e si stabilisce nell'embrione, dove riprende il suo sviluppo solo al

momento della germinazione del seme. Vi appartengono Ustilago tritici,

a carico del frumento![]() , e Ustilago nuda, che colpisce

l'orzo

, e Ustilago nuda, che colpisce

l'orzo![]() . Questa

forma provoca nelle spighe la distruzione degli involucri fiorali e la

formazione sulle rachidi di aggregati fuligginosi scoperti, che si disperdono

facilmente: per tal motivo è detta carbone nudo o volante.

. Questa

forma provoca nelle spighe la distruzione degli involucri fiorali e la

formazione sulle rachidi di aggregati fuligginosi scoperti, che si disperdono

facilmente: per tal motivo è detta carbone nudo o volante.

Nel terzo tipo la

cariosside è sana e viene infettata da clamidospore presenti nel terreno o

casualmente aderenti al tegumento al momento della germinazione del seme: si

dice carbone aggregato o fisso, o anche carbone coperto in quanto i sori

carboniosi che produce rimangono localizzati negli ovari della pianta, e

quindi nascosti per un certo tempo dalle glume o glumette. Vi appartengono Ustilago

hordei (carbone aggregato dell'orzo) e Ustilago levis (carbone

aggregato dell'avena![]() ).

).

Il rimedio per combattere le varie forme di carbone consiste nel trattamento preventivo dei semi, che vengono immersi per alcuni minuti in acqua riscaldata a 50 ºC, oppure esposti a correnti d'aria a temperature elevate; le piante colpite vanno estirpate e bruciate.

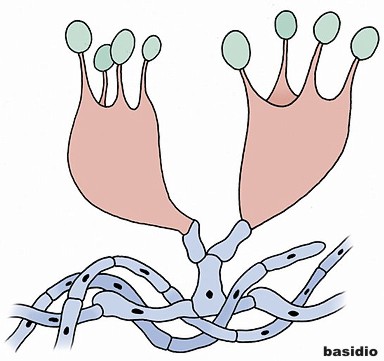

Basidiomycota - Nel regno dei Funghi la divisione Basidiomycota (R.H. Whittaker, Q. Rev. Biol. 34: 220, 1959) comprende quei gruppi di funghi che hanno micelio settato, riproduzione sessuata e asessuata con produzione di basidi (sporangio dei Basidiomiceti, costituito dalla porzione terminale di un'ifa, generalmente ingrossata a clava e separata da un setto) e spore non mobili. Ordini di Basidiomycota: Basidiomycetes G. Winter (1880) - Urediniomycetes D. Hawksw., B. Sutton & Ainsw. (1983) - Ustilaginomycetes R. Bauer, Oberw. & Vánky (1997) - Wallemiomycetes.

Basidiomycetes è una classe di funghi caratterizzata dalla produzione di spore (di solito quattro) all'esterno di una cellula, solitamente a forma clavata, chiamata basidio. La prima applicazione dei Basidiomiceti è quella riguardante il consumo di funghi mangerecci, alcuni dei quali vengono coltivati su larga scala (es. Agaricus bisporus, Pleurotus). La coltivazione di questi funghi avviene a partire da scarti lignocellulosici e letami di diversa origine contribuendo al loro smaltimento. Inoltre dal substrato di coltivazione si ottiene un sottoprodotto, il compost, impiegato come ammendante e fertilizzante del suolo.

Alcuni basidiomiceti sono conosciuti fin dall’antichità per le loro proprietà medicinali; ad esempio Ganoderma lucidum, Trametes versicolor, Fomes fomentarius, Tremella fuciformis e Lentinula edodes erano già conosciute nella medicina tradizionale cinese. Attualmente sono riconosciute dalla medicina ufficiale per le loro proprietà terapeutiche più di 270 specie di basidiomiceti, alcune delle quali sono prodotte a livello industriale.

Alcuni funghi come Trametes odorata, producono monoterpeni dall’aroma dolce (linalolo) o di rosa (geraniolo e nerolo). Altri vengono utilizzati nella produzione del mentolo. I funghi del marciume bianco sono in grado di trasformare la lignina in composti organici volatili utilizzati come aromi nell’industria alimentare (alcool aromatici, aldeidi, terpeni); i più utilizzati sono la benzaldeide (aroma di mandorla impiegato nell’industria cosmetica e alimentare) e la vanillina.

I

funghi del marciume bianco sono gli unici organismi viventi in grado di

mineralizzare completamente la lignina. L’uso di questi funghi o dei loro

enzimi negli ultimi anni è incrementato moltissimo sia a livello industriale,

principalmente nell’industria della carta, sia a livello ambientale, nei

processi di biorisanamento.

Attenzione: La determinazione di un fungo e la sua commestibilità va affidata

a micologi esperti e certificati, o ai centri di controllo delle ASL. Non

azzardare il consumo di funghi, potresti mettere a repentaglio la salute e

persino la vita tua e dei tuoi commensali.

Ustilago is a genus of smut fungi parasitic on grasses. There is a large research community that works on Ustilago maydis including researchers at the University of Georgia, Philipps-Universität Marburg, University of British Columbia and others. Research with this organism has led to better understanding of the genetics underlying self-non-self recognition through elucidation of the mating type system as well as fundamental aspects of signal transduction and cell-cycle regulation. Ustilago maydis is also eaten as a traditional Mexican food known as huitlacoche corn smut. The genome of Ustilago maydis was sequenced.

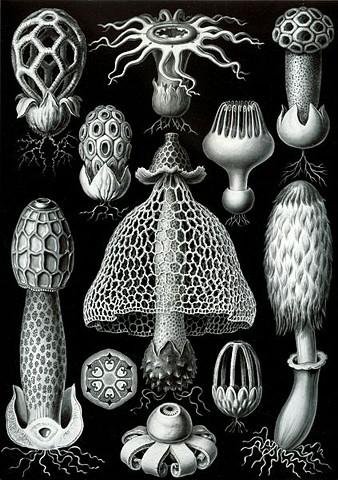

Basidiomycota

The

63rd plate from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur (1904)

depicting organisms classified as Basimycetes

Basidiomycota is one of two large phyla that, together with the Ascomycota, comprise the subkingdom Dikarya (often referred to as the "Higher Fungi") within the Kingdom Fungi. More specifically the Basidiomycota include mushrooms, puffballs, stinkhorns, bracket fungi, other polypores, jelly fungi, boletes, chanterelles, earth stars, smuts, bunts, rusts, mirror yeasts, and the human pathogenic yeast, Cryptococcus. Basically, Basidiomycota are filamentous fungi composed of hyphae (except for those forming yeasts), and reproducing sexually via the formation of specialized club-shaped end cells called basidia that normally bear external meiospores (usually four). These specialized spores are called basidiospores. However, some Basidiomycota reproduce asexually, and may or may not also reproduce sexually. Asexually reproducing Basidiomycota (discussed below) can be recognized as members of this phylum by gross similarity to others, by the formation of a distinctive anatomical feature (the clamp connection - see below), cell wall components, and definitively by phylogenetic molecular analysis of DNA sequence data.

The most recent classification adopted by a coalition of 67 mycologists recognizes 3 subphyla (Pucciniomycotina, Ustilaginomycotina, Agaricomycotina) and 2 other class level taxa (Wallemiomycetes, Entorrhizomycetes) outside of these, among the Basidiomycota. As now classified, the subphyla join and also cut across various obsolete taxonomic groups (see below) previously commonly used to describe various Basidiomycota.

The Basidiomycota had traditionally been divided into 2 obsolete classes, the Homobasidiomycetes (including true mushrooms); and the Heterobasidiomycetes (the Jelly, Rust and Smut fungi). Previously the entire Basidiomycota were called Basidiomycetes, an invalid class level name coined in 1959 as a counterpart to the Ascomycetes, when neither of these taxa were recognized as phyla. The terms basidiomycetes and ascomycetes are frequently used loosely to refer to Basidiomycota and Ascomycota. They are often abbreviated to "basidios" and "ascos" as mycological slang.

The Agaricomycotina (see details on that page) includes what had previously been called the Hymenomycetes (an obsolete morphological based class of Basidiomycota that formed hymenial layers on their fruitbodies), the Gasteromycetes (another obsolete class that included species mostly lacking hymenia and mostly forming spores in enclosed fruitbodies), as well as most of the jelly fungi.

The Ustilaginomycotina are most (but not all) of the former smut fungi and along with the Exobasidiales. The Pucciniomycotina includes the rust fungi, the insect parasitic/symbiotic genus Septobasidium, a former group of smut fungi (in the Microbotryomycetes, which includes mirror yeasts), and a mixture of odd, infrequently seen or seldom recognized fungi, often parasitic on plants. Two classes, Wallemiomycetes and Entorrhizomycetes cannot at present be placed in a subphylum.

Unlike higher animals and plants which have readily recognizable male and female counterparts, Basidiomycota (except for the Rust (Pucciniales)) tend to have mutually indistinguishable, compatible haploids which are usually mycelia being composed of filamentous hyphae. Typically haploid Basidiomycota mycelia fuse via plasmogamy and then the compatible nuclei migrate into each other's mycelia and pair up with the resident nuclei. Karyogamy is delayed, so that the compatible nuclei remain in pairs, called a dikaryon. The hyphae are then said to be dikaryotic. Conversely, the haploid mycelia are called monokaryons. Often, the dikaryotic mycelium is more vigorous than the individual monokaryotic mycelia, and proceeds to take over the substrate in which they are growing. The dikaryons can be long-lived, lasting years, decades, or centuries. The monokaryons are neither male nor female. They have either a bipolar (unifactorial) or a tetrapolar (bifactorial) mating system. This results in the fact that following meiosis, the resulting haploid basidiospores and resultant monokaryons, have nuclei that are compatible with 50% (if bipolar) or 25% (if tetrapolar) of their sister basidiospores (and their resultant monokaryons) because the mating genes must differ for them to be compatible. However, there are many variations of these genes in the population, and therefore, over 90% of monokaryons are compatible with each other. It is as if there were multiple sexes.

The maintenance of the dikaryotic status in dikaryons in many Basidiomycota is facilitated by the formation of clamp connections that physically appear to help coordinate and re-establish pairs of compatible nuclei following synchronous mitotic nuclear divisions. Variations are frequent and multiple. In a typical Basidiomycota lifecycle the long lasting dikaryons periodically (seasonally or occasionally) produce basidia, the specialized usually club-shaped end cells, in which a pair of compatible nuclei fuse (karyogamy) to form a diploid cell. Meiosis follows shortly with the production of 4 haploid nuclei that migrate into 4 external, usually apical basidiospores. Variations occur, however. Typically the basidiospores are ballistic, hence they are sometimes also called ballistospores. In most species, the basidiospores disperse and each can start a new haploid mycelium, continuing the lifecycle. Basidia are microscopic but they are often produced on or in multicelled large fructifications called basidiocarps or basidiomes, or fruitbodies), variously called mushrooms, puffballs, etc. Ballistic basidiospores are formed on sterigmata which are tapered spine-like projections on basidia, and are typically curved, like the horns of a bull. In some Basidiomycota the spores are not ballistic, and the sterigmata may be straight, reduced to stubbs, or absent. The basidiospores of these non-ballistosporic basidia may either bud off, or be released via dissolution or disintegration of the basidia.

Schematic of a typical basidiocarp, the dipoid reproductive structure of a basidiomycete, showing fruiting body, hymenium and basidia.In summary, meiosis takes place in a diploid basidium. Each one of the four haploid nuclei migrates into its own basidiospore. The basidiospores are ballistically discharged and start new haploid mycelia called monokaryons. There are no males or females, rather there are compatible thalli with multiple compatibility factors. Plasmogamy between compatible individuals leads to delayed karyogamy leading to establishment of a dikaryon. The dikaryon is long lasting but ultimately gives rise to either fruitbodies with basidia or directly to basidia without fruitbodies. The paired dikaryon in the basidium fuse (i.e karyogamy takes place). The diploid basidium begins the cycle again.

Many variations occur. Some are self compatible and spontaneously form dikaryons without a separate compatible thallus being involved. These fungi are said to be homothallic, versus the normal heterothallic species with mating types. Others are secondarily homothallic, in that two compatible nuclei following meiosis migrate into each basidiospore, which is then dispersed as a pre-existing dikaryon. Often such species form only two spores per basidium, but that too varies. Following meiosis, mitotic divisions can occur in the basidium. Multiple numbers of basidiospores can result, including odd numbers via degeneration of nuclei, or pairing up of nuclei, or lack of migration of nuclei. For example, the chanterelle genus Craterellus often has 6-spored basidia, while some corticioid Sistotrema species can have 2-, 4-, 6-, or 8-spored basidia, and the cultivated button mushroom, Agaricus bisporus. can have 1-, 2-, 3- or 4-spored basidia under some circumstances. Occasionally monokaryons of some taxa can form morphologically fully formed basidiomes and anatomically correct basidia and ballistic basidiospores in the absence of dikaryon formation, diploid nuclei, and meiosis. A rare few number of taxa have extended diploid life-cycles, but can be common species. Examples exist in the mushroom genera Armillaria and Xerula, both in the Physalacriaceae. Occasionally basidiospores are not formed and parts of the "basidia" act as the dispersal agents, e.g. the peculiar mycoparasitic jelly fungus, Tetragoniomyces or the entire "basidium" acts as a "spore", e.g. in some false puffballs (Scleroderma). In the human pathogenic genus Filobasidiella 4 nuclei following meiosis remain in the basidium but continually divide mitotically, each nucleus migrating into synchronously forming nonballistic basidiospores that are then pushed upwards by another set forming below them, resulting in 4 parallel chains of dry "basidiospores". Other variations occur, some as standard life-cycles (that themselves have variations within variations) within specific orders.

Rusts (Pucciniales, previously known as Uredinales) at their greatest complexity produce five different types of spores on two different hosts in two unrelated host families. Such rusts are heteroecious (requiring 2 hosts) and macrocyclic (producing all 5 spores types). Wheat stem rust is an example. By convention the stages and spore states are numbered by Roman numerals. Typically, basidiospores infect host one, the mycelium forms pycnidia, called spermagonia, which are miniature, flask-shaped, hollow, submicroscopic bodies embedded in host tissue (such as a leaf). This stage, numbered "0", produces single-celled, minute spores that ooze out in a sweet liquid and that act as nonmotile spermatia, and also protruding receptive hyphae. Insects and probably other vectors such as rain carry the spermatia from spermagonia to spermagonia, cross inoculating the mating types. Neither thallus is male or female. Once crossed, the dikaryons are established and a second spore stage is formed, numbered "I" and called aecia, which form dikaryotic aeciospores in dry chains in inverted cup-shaped bodies embedded in host tissue. These aeciospores then infect the second host genus and cannot infect the host on which they are formed (in macrocyclic rusts). On the second host a repeating spore stage is formed, numbered "II", the urediospores in dry pustules called uredinia. Urediospores are dikaryotic and can infect the same host that produced them. They repeatedly infect this host over the growing season. At the end of the season, a fourth spore type, the teliospore, is formed. It is thicker-walled and serves to overwinter or to survive other harsh conditions. It does not continue the infection process, rather it remains dormant for a period and then germinates to form basidia (stage "IV"), sometimes called a promycelium. In the Pucciniales, the basidia are cylindrical and become 3-septate after meiosis, with each of the 4 cells bearing one basidiospore each. The basidospores disperse and start the infection process on host 1 again. Autoecious rusts complete their life-cycles on one host intead of two, and microcyclic rusts cut out one or more stages.

The characteristic part of the life-cycle of smuts is the thick-walled, often darkly pigmented, ornate, teliospore that serves to survive harsh conditions such as overwintering and also serves to help disperse the fungus as dry diaspores. The teliospores are initially dikaryotic but become diploid via karyogamy. Meiosis takes place at the time of germination. A promycelim is formed that consists to a short hypha (equated to a basidium). In some smuts such as Ustilago maydis the nuclei migrate into the promycelium that becomes septate, and haploid yeast-like conidia/basidiospores sometimes called sporidia, bud off laterally from each cell. In various smuts, the yeast phase may proliferate, or they may fuse, or they may infect plant tissue and become hyphal. In other smuts, such as Tilletia caries, the elongated haploid basidiospores form apically, often in compatible pairs that fuse centrally resulting in "H"-shaped diaspores which are by then dikaryotic. Dikaryotic conidia may then form. Eventually the host is infected by infectious hyphae. Teliospores form in host tissue. Many variations on these general themes occur.

Smuts with both a yeast phase and an infectious hyphal state are examples of dimorphic Basidiomycota. In plant parasitic taxa, the saprotrophic phase is normally the yeast while the infectious stage is hyphal. However, there are examples of animal and human parasites where the species are dimorphic but it is the yeast-like state that is infectious. The genus Filobasidiella forms basidia on hyphae but the main infectious stage is more commonly known by the anamorphic yeast name Cryptococcus, e.g. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii.

The dimorphic Basidiomycota with yeast stages and the pleiomorphic rusts are examples of fungi with anamorphs, which are the asexual stages. Some Basidiomycota are only known as anamorphs. Many are yeasts, collectively called basidiomycetous yeasts to differentiate them from ascomycetous yeasts in the Ascomycota. Aside from yeast anamorphs, and uredinia, aecia and pycnidia, some Basidiomycota form other distinctive anamorphs as parts of their life-cycles. Examples are Collybia tuberosa with its apple-seed-shaped and coloured sclerotium, Dendrocollybia racemosa with its sclerotium and its Tilachlidiopsis racemosa conidia, Armillaria with their rhizomorphs, Hohenbuehelia with their Nematoctonus nematode infectious, state and the coffee leaf parasite, Mycena citricolor and its Decapitatus flavidus propagules called gemmae.