Lessico

Cimice

Le cimici

usate in medicina antica pare fossero quelle appartenenti alla famiglia

Cimicidi, il cui prototipo è rappresentato da Cimex lectularius![]() ,

la cimice dei letti, che è ematofaga e che si nutre a spese di animali a

sangue caldo. Dioscoride

,

la cimice dei letti, che è ematofaga e che si nutre a spese di animali a

sangue caldo. Dioscoride![]() in II,33 – Cimices lectularii

– afferma che sono utili contro il morso della vipera, oltre a consigliarne

l'impiego in altre patologie. Pierandrea Mattioli

in II,33 – Cimices lectularii

– afferma che sono utili contro il morso della vipera, oltre a consigliarne

l'impiego in altre patologie. Pierandrea Mattioli![]() nel commento a questo capitolo non dissente da Dioscoride e afferma altresì

che le cimici che si nutrono di vegetali, cioè fitofaghe come per esempio la Palomena

viridissima

nel commento a questo capitolo non dissente da Dioscoride e afferma altresì

che le cimici che si nutrono di vegetali, cioè fitofaghe come per esempio la Palomena

viridissima![]() della famiglia dei Pentatomidi, non avrebbero alcun potere terapeutico.

della famiglia dei Pentatomidi, non avrebbero alcun potere terapeutico.

Più

problematico è interpretare il passo di Plinio![]() (XXIX,61) in cui si afferma che le galline che hanno mangiato cimici sono

anch'esse protette dal morso di vipera. Dovremmo ammettere che le galline

entrano in casa e vanno a caccia di cimici dei letti parassite dell'uomo. Però

si asserisce che esistono cimici della famiglia Cimicidi,

cui appartiene la cimice dei letti, per esempio Cimex hemipterus, le

quali parassitano i polli e i pipistrelli (poultry and bats). Per cui, anche

nel caso di Plinio, dobbiamo rimanere nel campo dei Cimicidi ematofagi,

Emitteri Eterotteri tanto come Cimex lectularius.

(XXIX,61) in cui si afferma che le galline che hanno mangiato cimici sono

anch'esse protette dal morso di vipera. Dovremmo ammettere che le galline

entrano in casa e vanno a caccia di cimici dei letti parassite dell'uomo. Però

si asserisce che esistono cimici della famiglia Cimicidi,

cui appartiene la cimice dei letti, per esempio Cimex hemipterus, le

quali parassitano i polli e i pipistrelli (poultry and bats). Per cui, anche

nel caso di Plinio, dobbiamo rimanere nel campo dei Cimicidi ematofagi,

Emitteri Eterotteri tanto come Cimex lectularius.

Ma i polli, in fin dei conti, mangiano le cimici fitofaghe? Sì, le divorano con ingordigia, ve lo posso assicurare. Ho voluto fare un esperimento per verificare se si astengono dall'ingoiarle per il fetore che emanano: non ci rinunciano affatto. Per cui nel caso di Plinio dobbiamo ammettere 3 possibilità: le sue galline immuni contro la vipera avevano mangiato le cimici parassite dell'uomo entrando in casa, oppure avevano mangiato le ematofaghe che si ritrovavano tra le piume o sui posatoi, oppure avevano mangiato cimici fitofaghe che magari erano ugualmente efficaci contro il morso della vipera..

Cimex lectularius - Cimice dei letti

Cimice in greco

suona kóris,

in latino cimex-micis. Nome comune degli Insetti Emitteri, sottordine

Eterotteri![]() ,

suddivisi in numerose famiglie, tra cui la famiglia Cimicidi cui appartiene l'aborrita

cimice

dei letti. In senso figurato: detto di persone ripugnanti per sporcizia,

avidità, meschinità: «ha un cuore di cimice» (Foscolo). Per estensione,

puntina da disegno, così chiamata perché la si conficca premendola con il

dito come si farebbe per schiacciare l'insetto.

,

suddivisi in numerose famiglie, tra cui la famiglia Cimicidi cui appartiene l'aborrita

cimice

dei letti. In senso figurato: detto di persone ripugnanti per sporcizia,

avidità, meschinità: «ha un cuore di cimice» (Foscolo). Per estensione,

puntina da disegno, così chiamata perché la si conficca premendola con il

dito come si farebbe per schiacciare l'insetto.

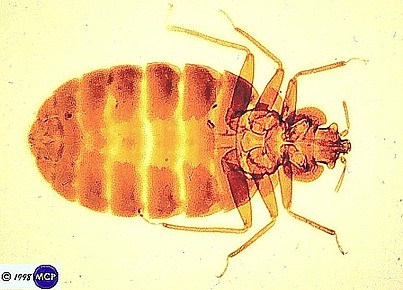

La cimice dei letti, Cimex lectularius, lunga pochi millimetri, rossiccia, appiattita, è parassita dell'uomo, oltre che di talune specie animali a sangue caldo. Frequenta tra l'altro le abitazioni poco pulite e sovraffollate. La sua puntura, dolorosa, è sospettata come mezzo di trasmissione di malattie di varia natura. Conduce un'esistenza prettamente notturna; le femmine depongono le uova, in gruppi di alcune centinaia, nelle fessure dei muri, dei mobili, ecc.

Le cimici

delle piante appartengono spesso alla famiglia dei Pentatomidi, cioè con le

antenne suddivise in 5 segmenti. Questa famiglia è costituita da insetti

Emitteri del sottordine Eterotteri![]() .

Fitofagi, i Pentatomidi comprendono numerosissime specie caratterizzate

appunto da antenne costituite da 5 segmenti, da un rostro lungo, da tarsi con

2-3 articoli. Spesso colorati vivacemente, secernono un liquido dall'odore

nauseabondo, sgradevole e persistente, prodotto da due ghiandole situate nel

torace. Con questo odore, che permane sulle piante da essi visitate, i

Pentatomidi si proteggono dai nemici.

.

Fitofagi, i Pentatomidi comprendono numerosissime specie caratterizzate

appunto da antenne costituite da 5 segmenti, da un rostro lungo, da tarsi con

2-3 articoli. Spesso colorati vivacemente, secernono un liquido dall'odore

nauseabondo, sgradevole e persistente, prodotto da due ghiandole situate nel

torace. Con questo odore, che permane sulle piante da essi visitate, i

Pentatomidi si proteggono dai nemici.

La

famiglia dei Pentatomidi comprende più di 5000 specie, la più nota delle

quali è Palomena viridissima![]() ,

la cimice verde degli orti e dei frutteti. I Pentatomidi possono essere, oltre

che verdi, grigi e marroni, e alcuni di essi hanno vistose colorazioni rosse e

nere o gialle e nere. Le abitudini alimentari di questi insetti sono diverse:

alcuni sono esclusivamente carnivori, altri si cibano solo di vegetali. Fra le

numerose cimici parassite di piante, la cimice delle nocciole (Gonocerus

acuteangulatus) appartiene alla famiglia Coreidi

,

la cimice verde degli orti e dei frutteti. I Pentatomidi possono essere, oltre

che verdi, grigi e marroni, e alcuni di essi hanno vistose colorazioni rosse e

nere o gialle e nere. Le abitudini alimentari di questi insetti sono diverse:

alcuni sono esclusivamente carnivori, altri si cibano solo di vegetali. Fra le

numerose cimici parassite di piante, la cimice delle nocciole (Gonocerus

acuteangulatus) appartiene alla famiglia Coreidi![]() - anch'essi Emitteri Eterotteri - ed è lunga sino a 15 mm.

- anch'essi Emitteri Eterotteri - ed è lunga sino a 15 mm.

Cimice dei letti

Cimex lectularius - Cimice dei letti

Le cimici dei letti (Cimex lectularius), cioè le cimici più diffuse, sono una specie di piccoli insetti dal corpo piatto e ovale appartenenti all'ordine dei Rincoti. Fino a pochi anni fa questa specie, parassita dell'uomo, era considerata quasi scomparsa, mentre negli ultimi anni le segnalazioni si stanno moltiplicando. Negli USA nel 2002 ci sono state solo due segnalazioni mentre nel 2006 sono arrivate a quota 1200. L'insetto è privo di ali e di giorno si nasconde nei materassi e nelle crepe dei mobili, di notte esce e succhia il sangue di chi dorme. Si ritiene che la sua diffusione sia stata favorita da un graduale depotenziamento degli insetticidi e dall'aumento dei viaggi internazionali.

Il loro colore predominante è il marrone. Non rivestono una particolare importanza in parassitologia se non per le reazioni allergiche che possono provocare in alcuni soggetti dopo la puntura. Infatti, non risulta che trasmetta malattie.

Cimex lectularius

A bedbug (or bed bug) is a small nocturnal insect of the family Cimicidae that lives by hematophagy, or by feeding on the blood of humans and other warm-blooded hosts.

Biology

The common bedbug (Cimex lectularius) is the best adapted to human environments. It is found in temperate climates throughout the world and lives off the blood of humans. Other species include Cimex hemipterus, found in tropical regions, which also infests poultry and bats, and Leptocimex boueti, found in the tropics of West Africa and South America, which infests bats and humans. Cimex pilosellus and Cimex pipistrella primarily infest bats, while Haematosiphon inodora, a species of North America, primarily infests poultry. Oeciacus, while not strictly a bedbug, is a closely related genus primarily affecting birds.

Adult bedbugs are a reddish-brown, flattened, oval, and wingless, with microscopic hairs that give them a banded appearance. A common misconception is that they are not visible to the naked eye. Adults grow to 4-5 mm (1/8th - 3/16th of an inch) in length and do not move quickly enough to escape the notice of an attentive observer. Newly hatched nymphs are translucent, lighter in color and continue to become browner and moult as they reach maturity. When it comes to size, they are often compared to lentils or appleseeds. A recent paper by Professor Brian J. Ford and Dr Debbie Stokes gives views of a bedbug under various microscopes.

Bedbug

4 mm length 2.5 mm width shown in a film roll plastic container.

On the right is the sloughed off skin, which this bedbug just recently wore

during its nymph form.

Feeding habits

Bedbugs are generally active only at dawn, with a peak feeding period about an hour before sunrise. They may attempt to feed at other times, however, given the opportunity, and have been observed to feed at any time of the day. Attracted by warmth and the presence of carbon dioxide, the bug pierces the skin of its host with two hollow tubes. With one tube it injects its saliva, which contains anticoagulants and anesthetics, while with the other it withdraws the blood of its host. After feeding for about five minutes, the bug returns to its hiding place. The bites cannot usually be felt until some minutes or hours later, as a dermatological reaction to the injected agents, and the first indication of a bite usually comes from the desire to scratch the bite site.

Although bedbugs can live for a year or as much as eighteen months without feeding, they typically seek blood every five to ten days. Bedbugs that go dormant for lack of food often live longer than a year, well-fed specimens typically live six to nine months. Low infestations may be difficult to detect, and it is not unusual for the victim not to even realize they have bedbugs early on. Patterns of bites in a row or a cluster are typical as they may be disturbed while feeding. Bites may be found in a variety of places on the body.

Bedbugs may be erroneously associated with filth in the mistaken notion that this attracts them. Bedbugs are attracted by exhaled carbon dioxide and body heat, not by dirt, and they feed on blood, not waste. In short, the cleanliness of their environments has effect on the control of bedbugs but, unlike cockroaches, does not have a direct effect on bedbugs as they feed on their hosts and not on waste. Good housekeeping in association with proper preparation and mechanical removal by vacuuming will certainly assist in control.

Reproduction

All bedbugs mate via a process termed traumatic insemination. Instead of inserting their genitalia into the female's reproductive tract as is typical in copulation, males instead pierce females with hypodermic genitalia and ejaculate into the body cavity. This form of mating is thought to have evolved as a way for males to overcome female mating resistance. Traumatic insemination imposes a cost on females in terms of physical damage and increased risk of infection. To reduce these costs females have evolved internal and external "paragenital" structures collectively known as the “spermalege”. Within the True Bugs (Heteroptera) traumatic insemination occurs in the Prostemmatinae (Nabidae) and the Cimicoidea (Anthocoridae, Plokiophilidae, Lyctocoridae, Polyctenidae and Cimicidae), and has recently been discovered in the plant bug genus Coridromius (Miridae).

Remarkably, in the genus Afrocimex both males and females possess functional external paragenitalia, and males have been found with copulatory scars and the ejaculate of other males in their haemolymph. There is a widespread misbelief that males inseminated by other males will in turn pass the sperm of both themselves and their assailants onto females with whom they mate. While it is true that males are known to mate with and inject sperm into other males, there is however no evidence to suggest that this sperm ever fertilizes females inseminated by the victims of such acts.

Young

Female bedbugs can lay up to five eggs in a day and 500 during a lifetime. The eggs are visible to the naked eye measuring 1 mm in length (approx. two grains of salt) and are a milky-white tone. The eggs hatch in one to two weeks. The hatchlings begin feeding immediately. They pass through five molting stages before they reach maturity. They must feed once during each of these stages. At room temperature, it takes only about five weeks for a bedbug to pass from hatching to maturity. They become reproductively active only at maturity.

Bites

In most observed cases a small, hard, swollen, white welt may develop at the site of each bedbug bite. This is often surrounded by a slightly raised red bump and is usually accompanied by severe itching that lasts for several hours to days. Welts do not have a red spot in the center such as is characteristic of flea bites. In other cases, it is observed that welts first appear upon the incessant scratching that is triggered by the bite, and seem like a mosquito bite that increases in size upon scratching. Later, however, the welts subside but tend not to disappear like those from mosquitos, and persist for up to several weeks. This usually depends on the person's skin type, environment and the species of bug.

Some individuals respond to bed bug infestations and their bites with anxiety, stress, and insomnia. Individuals may also get skin infections and scars from scratching the bedbug bite locations. Most patients who are placed on systemic corticosteroids to treat the itching and burning often associated with bed bug bites find that the lesions are poorly responsive to this method of treatment. Antihistamines have been found to reduce itching in some cases, but they do not affect the appearance and duration of the lesions. Topical corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone, have been reported to expediently resolve the lesions and decrease the associated itching.

Diseases transmission

Bedbugs seem to possess all of the necessary prerequisites for being capable of passing diseases from one host to another, but there have been no known cases of bed bugs passing disease from host to host. There are at least twenty-seven known pathogens (some estimates are as high as forty-one) that are capable of living inside a bed bug or on its mouthparts. Extensive testing has been done in laboratory settings that also conclude that bed bugs are unlikely to pass disease from one person to another. Therefore bedbugs are less dangerous than some more common insects such as the flea. However, transmission of Chagas disease or hepatitis B might be possible in appropriate settings.

The salivary fluid injected by bed bugs typically causes the skin to become irritated and inflamed, although individuals can differ in their sensitivity. Anaphylactoid reactions produced by the injection of serum and other nonspecific proteins are observed and there is the possibility that the saliva of the bedbugs may cause anaphylactic shock in a small percentage of people. It is also possible that sustained feeding by bedbugs may lead to anemia. It is also important to watch for and treat any secondary bacterial infection.

History USA

Bedbugs were originally brought to the United States by early colonists from Europe. Bedbugs thrive in places with high occupancy, such as hotels. Bedbugs were believed to be altogether eradicated 50 years ago in the United States and elsewhere with the widespread use of DDT. Some current theories suggest they never really left. One recent theory about bedbug reappearance involves potential geographic epicenters. Investigators have found two apparent United States epicenters at poultry facilities in Arkansas and Texas. It was determined that workers in these facilities were the main spreaders of these bedbugs, unknowingly carrying them to their places of residence and elsewhere after leaving work. Bedbug populations in the United States have increased by 500 percent in the past few years. The cause of this resurgence is still uncertain, but most believe it is related to increased international travel and the use of new pest-control methods that do not affect bedbugs. In the last few years, the use of baits rather than insecticide sprays is believed to have contributed to the increase.

History New York City

New York City has been riddled with bedbug infestations since the early 21st century. Bedbugs have found their way into hotels, schools, and even hospital maternity wards. Jeffrey Eisenberg, owner of Pest Away Exterminating on the Upper West Side, claims his company currently receives 125 calls a week, compared to only a few just five years ago. In 2004, New York City had 377 bedbug violations. However, in the five-month span from July to November 2005, 449 violations were reported in the city, an alarming increase in infestations over a short period of time. Exterminators and entomology experts believe this is because so many international travelers visit New York each day.

Global resurgence

Bedbug cases have been on the rise recently across the world. Prior to the mid-twentieth century, bedbugs were very common. According to a report by the UK Ministry of Health, in 1933 there were many areas where all the houses had some degree of bedbug infestation. Since the mid-1990s, reports of bedbug cases have been rising. Figures from one London borough show reported bedbug infestations doubling each year from 1995 to 2001. The rise in bedbug infestations has been hard to track because bedbugs are not an easily identifiable problem. Most of the reports are collected from pest-control companies, local authorities, and hotel chains. Therefore, the problem may be more severe than is currently believed.

As stated above, the most-cited reason for the dramatic worldwide rise in bedbug cases in recent decades is increased international travel. In 1999, four separate infestations throughout the United Kingdom alerted people to the possibility of an increase in the worldwide bedbug population, facilitated by international travel and trade. However, there is evidence of a previous cycle of bedbug infestations in the United Kingdom. The Institution of Environmental Health Officers maintained statistics for bedbug infestations -- data collected from reports and inspections. In the period 1985-1986, the Institution of Environmental Health Officers reported treating 7,771 infestations in England and Wales, and 6,179 infestations in 1986-1987. There were also reports of infestations in Belfast and in Scotland.

Since 1999, infestations have been reported in the United Kingdom, Germany, Spain, Australia, Canada, India, Israel and the United States. Two separate studies in Tuscany, Italy offer further correlation of international travel with a resurgence in bedbug infestations. In case 1, in summer 2003 a seven-year-old boy developed a number of papulae that caused severe itching on his lower legs. His parents suspected insects in the boy’s room, and found several in the folds of his mattress. Two specimens were identified as C. lectularius and the room was treated with an insecticide. The house had never been infested with bedbugs before. However, one month earlier, two family friends had flown from Nepal to stay with the family for ten days. In Case 2, a forty-eight-year-old man traveled by car to Pisa, Italy from Prague, Czech Republic in June 2003 and stayed in a rented house with three friends. After several days, the man noticed several bullous eruptions in linear patterns of three on his upper and lower extremities. The man found several insects in his room that were identified as C. lectularius. The rented house was well kept and had never had a bedbug infestation. However, a group of Germans had rented the house a few weeks before the Czech group arrived.

Bedbugs had nearly been eradicated by the widespread use of potent insecticides such as DDT. However, many of these strong insecticides have been banned from the United States and replaced with weaker insecticides such as pyrethroids. Many bedbugs have grown resistant to the weaker insecticides. In a study at the University of Kentucky bedbugs were randomly collected from across the United States. These “wild” bedbugs were up to several thousands of times more resistant to pyrethroids than were laboratory bedbugs. Another problem with current insecticide use is that the broad-spectrum insecticide sprays for cockroaches and ants that are no longer used had a collateral impact on bedbug infestations. Recently, a switch has been made to bait insecticides that have proven effective against cockroaches but have allowed bedbugs to escape the indirect treatment.

The number of bedbug infestations has risen significantly since the early 21st century. The National Pest Management Association reported a 71% increase in bedbug calls between 2000 and 2005. The Steritech Group, a pest-management company based in Charlotte, North Carolina, claimed that 25% of the 700 hotels they surveyed between 2002 and 2006 needed bedbug treatment. In 2003, a brother and sister staying at a Motel 6 in Chicago were awarded $372,000 in punitive damages after being bitten by bedbugs during their stay. These are only a few of the reported cases since the turn of the 21st century.

Infestations

There are several means by which dwellings can become infested with bedbugs. People can often acquire bedbugs at hotels, motels, or bed-and-breakfasts, and bring them back to their homes in their luggage. They also can pick them up by inadvertently bringing infested furniture or used clothing to their household. If someone is in a place that is severely infested, bedbugs may actually crawl onto and be carried by people's clothing, although this is atypical behavior — except in the case of severe infestations, bedbugs are not usually carried from place to place by people on clothing they are currently wearing. Bedbugs may travel between units in multi-unit dwellings, such as condominiums and apartment buildings, after being originally brought into the building by one of the above routes. Bedbugs can also be transmitted via animal vectors including wild birds and household pets.

This spread between sites is dependent in part on the degree of infestation, on the material used to partition units and whether infested items are dragged through common areas while being disposed of, resulting in the shedding of bedbugs and bedbug eggs while being dragged. In some exceptional cases, the detection of bedbug hiding places can be aided by the use of dogs that have been trained to signal find the insects by their scent much as dogs are trained to find drugs or explosives. A trained dog and handler can detect and pinpoint a bedbug infestation within minutes. This is a fairly costly service that is not used in the majority of cases, but can be very useful in difficult cases.

The numerical size of a bedbug infestation is to some degree variable, as it is a function of the elapsed time from the initial infestation. With regards to the elapsed time from the initial infestation, even a single female bedbug brought into a home has a potential for reproduction, with its resulting offspring then breeding, resulting in a geometric progression of population expansion if control is not undertaken. Sometimes people are not aware of the insects and do not notice the bites. The visible bedbug infestation does not represent the infestation as a whole, as there may be infestations elsewhere in a home. However, the insects do have a tendency to stay close to their hosts, hence the name "bed" bugs.

Locations

Blood-fed Cimex lectularius

Bedbugs travel easily and quickly along pipes and boards, and their bodies are very flat, which allows them to hide in tiny crevices. In the daytime, they tend to stay out of the light, preferring to remain hidden in such places as mattress seams, mattress interiors, bed frames, nearby furniture, carpeting, baseboards, inner walls, tiny wood holes, or bedroom clutter. Bedbugs can be found on their own, but more often congregate in groups. Bedbugs are capable of travelling as far as 100 feet to feed, but usually remain close to the host in bedrooms or on sofas where people may sleep.

Detection

Bedbugs are known for being elusive, transient, and nocturnal, making them difficult to detect. While individuals have the option of contacting a pest control professional to determine if a bedbug infestation exists, there are several do-it-yourself methods that may work equally well. The presence of bedbugs may be confirmed through identification of the insects collected or by a pattern of bites. Though bites can occur singularly, they often follow a distinctive linear pattern marking the paths of blood vessels running close to the surface of the skin. The common bite pattern of three bites often around the ankle or shin close to each other has garnered the macabre colloquialism "breakfast, lunch & dinner."

A technique for catching bedbugs in the act is to have a light source quickly accessible from your bed and to turn it on at about an hour before dawn, which is usually the time when bedbugs are most active. A flashlight/torch is recommended instead of room lights, as the act of getting out of bed will cause any bedbugs present to scatter before you can catch them. If you awaken during the night, leave your lights off but use your flashlight/torch to inspect your mattress. Bedbugs are fairly fast in their movements, about equal to the speed of ants. They may be slowed down if engorged. When the bedroom light is switched on, it may temporarily startle them allowing time for you to get a dust pan and brush kept next to the bed and sweep the bugs into the pan then immediately sweep them into a cup or mug full of water where the bugs drown quickly. Dispose of the water down the sink or toilet. Disinfect the mattress, skirting boards and so on regularly.

Glue traps placed in strategic areas around the home, sometimes used in conjunction with heating pads or balloons filled with exhaled breath offering a carbon dioxide source, may be used to trap and thus detect bedbugs. This method has varied reports of success. There are also commercial traps like 'flea' traps whose effectiveness is questionable except perhaps as a means of detection. Perhaps the easiest trapping method is to place double-sided carpet tape in long strips near or around the bed and check the strips after a day or more.

Control

With the widespread use of DDT in the 1940s and '50s, bedbugs all but disappeared from North America in the mid-twentieth century. Infestations remained common in many other parts of the world and in recent years have also begun to rebound in North America. Reappearance of bedbugs has presented new challenges for pest control without DDT and similarly banned agents.

Another reason for their increase is that pest control services more often nowadays use low toxicity gel-based pesticides for control of cockroaches, the most common pest in structures, instead of residual sprays. When residual sprays meant to kill other insects were commonly being used, they resulted in a collateral insecticidal effect on potential bedbug infestations; the gel-based insecticides primarily used nowadays do not have any effect on bedbugs, as they are incapable of feeding on these baits.

The National Pest Management Association, a US advocacy group for pest management professionals conducted a "proactive bedbug public relations campaign" in 2005 and 2006, resulting in increased media coverage of bedbug stories and an increase in business for pest controllers, possibly distorting the scale of the increase in bedbug infestations.

If it is possible to create makeshift temporary barriers from the insects around a bed. Although bedbugs cannot fly or jump, they have been observed climbing a higher surface in order to then fall to a lower one, such as climbing a wall in order to fall onto a bed. Barrier strategies nevertheless often have beneficial effects: an elevated bed for example, can be protected by applying double-sided sticky tape around each leg, or by keeping each leg on a plastic furniture block in a tray of water.

Bed frames can be effectively rid of adult bedbugs and eggs by use of steam or by spraying rubbing alcohol on any visible insects, although this is not a permanent treatment. Small steam cleaners are available and are very effective for local treatment. A suspect mattress can be protected by wrapping it in disposable plastic sheeting, sealing shut all the seams and putting it on a protected bed after a final visual inspection. Bedding can be sanitized by a 120 °F (49 °C) laundry dryer. Once sanitized, bedding should not be allowed to drape to the floor. An effective way to quarantine a protected bed is to store sanitized sleeping clothes in the bed during the day, and bathing before entering the bed.

Food-grade diatomaceous earth (DE) can be sprinkled under mattresses, along baseboards and on the edges of bookshelves where bedbugs hide. Food-grade DE, although harmless to mammals, including common house pets and humans, is a virtual death sentence for bedbugs. DE is a drying agent and is actually used in many dry pet foods to keep the kibble dry and fresh.

The DE particles abrade the bedbug, essentially dehydrating it of water and lipids. Neem oil (mentioned below) can be added to the DE (1 cup DE to 20 drops neem oil) in a plastic bag before sprinkling it around. Other essential oils that can be added are juniper oil, eucalyptus oil, ylang ylang oil, rosemary oil and tea tree oil. The bedbugs hate the smell of the oils, and for those who don't and pass through, they will eventually be killed by the DE itself. Use 20 drops of each essential oil mentioned for each cup of DE.

Alternative treatments that may actually work better and be more comfortable than wrapping bedding in plastic that would cause sweating would be to encase your mattress and box springs in impermeable bed bug bite proof encasements after a treatment for an infestation. There are many products on the market but only some products have been laboratory tested to be bedbug bite proof. Make sure to check to see that the product you are considering is more than an allergy encasement, but is bed bug bite proof.

Vermin and pets will complicate a barrier strategy. Bedbugs prefer human hosts, but will resort to other warm-blooded hosts if humans are not available. Some bedbug species can live up to eighteen months without feeding at all. A co-infestation of mice can provide an auxiliary food source to keep bedbugs established for longer. Likewise, a house cat or human guest might easily defeat a barrier by sitting on a protected bed. Such considerations should be part of any barrier strategy.

BBC1 aired a television program entitled "The One Show" about the growth of bedbug infestations in London. In the program a pest control officer claimed that the use of insecticides alone was no longer an effective method to control bed bugs as they had developed a resistance to most if not all insecticides that might be used legally in the UK. He stated that insecticide use in conjunction to freezing bedbugs was the only effective control. All items of clothing and upholstery (including curtains) in the affected household had to be deep-frozen for at least 3 days in giant freezers to ensure complete eradication. The exact temperature at which bedbugs must be frozen was not mentioned.

Another method that might be useful in controlling bedbugs is the use of neem oil. It can be sprayed on carpets, curtains and mattresses. Neem oil is made from the leaves and bark of the neem tree native to India. It has been used safely for thousands of years in India both as a natural, effective insect repellent and it is antibacterial. It has recently received US Food and Drug Administration approval for external use. It is also possible to incorporate neem oil into certain types of mattress. Such mattresses are currently being manufactured by a German company.

Travel tips

Since most bedbugs are carried by travellers through contact with beds and hotel rooms of infected locations, following are some tips for those travelling to hotels that might be at risk.

First look at the room to seek potential hiding places for bedbugs, such as carpet edges, mattress seams, pillow case linings, bedboards, wall trim or other tiny crack-like places bedbugs might hide.

Next, look specifically at the mattress seams for signs of bedbug activity: droppings, eggs, bloodstains or even bedbugs themselves, hiding in tiny folds and seam lines.

As mentioned, keep a flashlight nearby when sleeping, to immediately observe activity during the night without having to get up out of bed, thus giving bedbugs time to hide in safety.

Never leave your clothing laying on the bed, or any location of possible infestation (as mentioned above). Instead, use hangers or hooks capable of keeping all cloth distant from the floor or bed.

Close your suitcase, travel bag, when you're not using it. This way, during the night the bugs may move over top of your luggage with greater difficulty to get inside.

Elevate your luggage off the floor to tables or chairs. These may also be hiding places, but less likely.

Keep any bedbug you find (intact if possible) to show the hotel owner.

If you have a bad feeling about a location, trust your instinct. Look carefully for possible activity, or change locations.

Current research

The Texas A&M Center for Urban and Structural Entomology and the University of Arkansas Department of Entomology have been collaborating to study bedbugs on a genetic level in the hopes to shed light on the their recent resurgence. By studying the genetic variation within bedbug populations, researchers can gain insight into insecticide resistance and insect dispersal. Researchers have two theories as to how bedbug resurgence has occurred in the United States. One theory is that the source of current bedbug populations is from other countries without bedbug pesticides that have made their way through air travel, and another theory is that the surviving bed bug populations were forced to switch hosts to birds, such as poultry, and bats. Since bedbugs have undergone a huge resurgence in poultry populations since the 1970s, theory two seems likely.

The theory that the surviving bedbug populations were forced to switch hosts to birds is also supported by the research done at Texas A&M and the University of Arkansas. In a recent study, researchers subjected 136 adult bedbugs from 22 sampled populations from nine U.S. states, Australia, and Canada to genetic analysis. Their finding concluded that the bedbug populations were never completely eradicated from the United States as there was no evidence of a genetic bottleneck in either the mitochondrial or nuclear DNA of the bedbugs. Researchers suspect that resistant populations of bedbugs have slowly been propagating in poultry facilities, and have made their way back to human hosts via the poultry workers.

Other research is being conducted at Texas A&M and Virginia Tech to be able to use bedbugs in forensic science. Researchers have been successful at isolating and characterizing human DNA taken from bedbug blood meals. One advantage that bedbugs have over other blood feeders being used in forensics is that they do not remain on the host, and instead remain in close proximity to the crime scene. Therefore bedbugs could potentially provide crucial evidence linking the suspect to the crime scene. Researchers are able to identify what hosts are being fed upon, and are taking further steps to be able to identify the individual by genotyping, and to predict the duration from the time of feeding to recovery of viable DNA.

Gli Eterotteri (Heteroptera Latreille, 1810 ) sono un sottordine di insetti dell'ordine dei Rincoti, comprendente circa 39.000 specie e diffuso in tutto il mondo. La denominazione comune di cimice si estende genericamente all'intero sottordine.

Gli Eterotteri hanno corpo con profilo oblungo, più o meno slanciato, oppure tozzo, di forma ovoidale, spesso depresso in senso dorso-ventrale. Le livree possono essere poco appariscenti, con colori più o meno uniformi, oppure presentare colori vivaci, spesso con caratteri aposematici, capaci cioè di indurre nei predatori un apprendimento più rapido e duraturo della loro sgradevolezza.

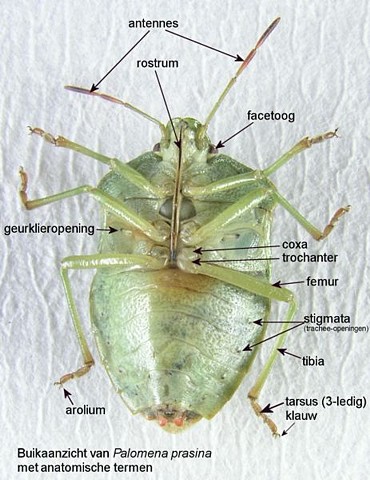

Il capo è relativamente piccolo, relativamente mobile, ipognato o metagnato. È provvisto di 2 ocelli oppure ne è privo; gli occhi sono in genere presenti e piuttosto grandi, spesso sporgenti o peduncolati. Le antenne sono relativamente lunghe e filiformi, composte da 3-5 articoli, talvolta brevi e non visibili dall'alto. Si inseriscono su protuberanze del cranio. In alcuni eterotteri sono presenti sul capo organi sensoriali, detti tricobotri composti da una fossetta contenente una setola sensoriale.

L'apparato

boccale è di tipo pungente-succhiante, con labbro superiore breve e di forma

triangolare, mandibole e mascelle trasformate in stiletti atti a perforare e

succhiare, labbro inferiore, detto rostro, composto da 3-4 articoli e

conformato a doccia per accogliere gli stiletti in fase di riposto. Ai lati

dell'inserzione del rostro sono presenti due espansioni laminari di origine

mascellare, dette bucculae, che possono nascondere o meno il primo

segmento del rostro alla vista laterale. La forma e lo sviluppo delle bucculae

sono elementi di determinazione tassonomica.

Il rostro si inserisce nella zona anteriore del capo nettamente separata dal

protorace da una regione sclerotizzata detta gola. Questo carattere distingue

gli Eterotteri dagli Omotteri. Nelle forme zoofaghe è generalmente breve,

spesso ricurvo, in quelle fitofaghe è piuttosto lungo e, in fase di riposo,

si distende ventralmente disponendosi fra le coxe.

Il torace mostra un pronoto abbastanza sviluppato, talvolta diviso in due parti, spesso di forma trapezoidale, allargandosi posteriormente. In diverse specie può presentare espansioni laterali o processi di varia forma e sviluppo. Mesotorace e metatorace sono visibili solo in parte, nelle forme alate, limitatamente allo scutello. Questo è in genere di forma triangolare e può estendersi posteriormente fino a ricoprire parte dell'addome. In alcuni Pentatomoidei può essere notevolmente sviluppato, fino a ricoprire interamente, o quasi, l'addome e le ali.

Nel metatorace è localizzato lo sbocco della ghiandola odorifera (o delle ghiandole). In base al numero si distinguono due tipi:

- il tipo omphalium, presente ad esempio nei Gerridi, è costituito da un unico sbocco impari e mediano, nel metasterno;

- il tipo diastomico, presente ad esempio nei Pentatomoidei, è costituito da due sbocchi pari e simmetrici, in corrispondenza delle metapleure.

Sbocco

della ghiandola odorifera

nel pentatomide Palomena prasina

Lo sbocco del dotto efferente della ghiandola è costituito da un solco, detto ostiolo, che si apre in una zona, detta area evaporante, con il tegumento morfologicamente distinto da quella circostante: l'area evaporante, infatti, si presenta rugosa o granulosa, allo scopo di accelerare l'evaporazione del secreto. La forma dell'area evaporante è un utile elemento di determinazione tassonomica. Negli stadi giovanili le ghiandole odorifere sono localizzate nell'addome e i loro efferenti si aprono in corrispondenza del bordo anteriore degli urotergiti IV-VI.

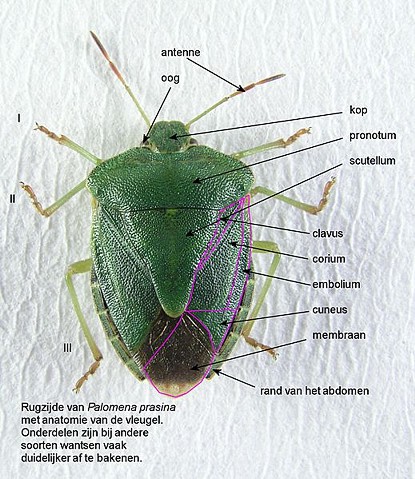

Nel sottordine sono presenti forme meiottere, anche attere, ma in genere le ali sono ben sviluppate e ricoprono interamente l'addome. Il carattere differenziale più evidente, che dà il nome al gruppo, è la conformazione dell'ala anteriore, trasformata in emielitra, ossia con l'area prossimale sclerificata e quella distale membranosa. Raramente le ali anteriori sono interamente e leggermente sclerificate (tegmine) oppure interamente membranose.

Nelle emielitre tipiche, la regione prossimale sclerificata è suddivisa da un solco in due aree, dette rispettivamente corio e clavo. Il solco decorre approssimativamente parallelo al margine dello scutello, configurando in modo caratteristico la morfologia delle ali. Il corio (o corium) si estende su gran parte della regione remigante e lungo il margine costale, il clavo (o clavus) è invece una ristretta area dislocata lungo il margine posteriore, adiacente allo scutello con le ali in riposo. In alcuni cimicomorfi (Miroidea e Anthocoridae), il corio differenzia, nella parte distale, un'area triangolare detta cuneo, separata dal corio da una linea più o meno marcata; l'area del corio parallela al margine costale è detta embolio. La parte distale delle emielitre, corrispondente alla metà o più piccola, è membranosa e trasparente e viene detta membrana. La membrana può essere più o meno ricca di nervature, il cui numero e sviluppo può essere un utile elemento di determinazione tassonomica. Le ali posteriori sono interamente membranose.

In fase di riposo le emielitre sono ripiegate sull'addome e tenute orizzontali, ricoprendo le posteriori e l'intero addome. La disposizione fa in modo che le aree membranose siano sovrapposte, i clavi delle due emielitre sono fra loro contrapposti e inframmezzati dallo scutello e i cori disposti più all'esterno. Pur essendo generalmente in grado di volare, gli Eterotteri non sono eccezionali volatori, ma diverse specie sono in grado di compiere migrazioni relativamente lunghe. Le ali dispongono di un apparato di collegamento abbastanza complesso: sul margine posteriore delle emielitre è presente una coppia di rilievi in cui si incastra un ispessimento del margine costale dell'ala posteriore.

Le zampe sono ben sviluppate e spesso presentano adattamenti morfofunzionali. In generale le zampe sono di tipo cursorio o deambulatorio. Quelle anteriori sono talvolta modificate nel tipo raptatorio (es. Nepoidea) nelle forme predatrici, oppure fossorio (es. Corissidi). Quelle medie e posteriori sono in genere trasformate in natatorie nelle forme prettamente acquatiche (Nepomorpha). Nei Gerromorpha sono spesso sottili e allungate e conformate in modo da consentire la locomozione sulla superficie dell'acqua. Nei Miridi, infine, quelle posteriori sono spesso di tipo saltatorio, con femori leggermente ingrossati. Nei Coreidi femori e tibie sono spesso appiattite e caratterizzate dalla presenza di processi di varia forma e sviluppo conferendo un aspetto bizzarro alla conformazione delle zampe posteriori. I tarsi sono in genere composti da tre segmenti, con pretarsi conformati in vario modo.

L'addome è generalmente depresso in senso dorso-ventrale e spesso presenta espansioni laterali appiattite, dette laterotergiti o paratergiti, che sporgono dalle emielitre. È composto da 9 uriti nel maschio e 10 nella femmina, ma l'ultimo è molto ridotto. I cerci sono assenti. In alcune forme acquatiche (Nepidi), l'ultimo urite presenta due sifoni più o meno lunghi, usati per attingere all'aria della superficie restando immersi, ma nella generalità degli Eterotteri le appendici addominali sono assenti.

Come si è

detto in precedenza, sul margine anteriore degli uriti 4-5 o 4-6 delle forme

giovanili si aprono i dotti escretori delle ghiandole odorifere. Nella parte

ventrale dei Pentatomomorfi sono presenti tricobotri, il cui numero e la cui

posizione costituiscono elementi di determinazione tassonomica.

L'ovopositore è presente in molte famiglie ed è composto da tre paia di

valve. L'apparato genitale maschile è asimmetrico in alcuni Cimicoidea

(Cimicidae e Anthocoridae), come asimmetrici può essere la

conformazione degli ultimi uriti dell'addome maschile.

L'apparato digerente è caratterizzato, come in tutti i Rincoti, dalla presenza della pompa faringeale, ossia uno sviluppo particolare della tunica della faringe associato a un sistema di muscoli dilatatori dorsali, atto a esercitare la suzione degli alimenti liquidi. L'esofago è breve, il mesentero è suddiviso in quattro porzioni da strozzature e, nelle forme fitomize, sono presenti diverticoli ciechi contenenti batteri simbionti. Il proctodeo è breve e a esso sono associati 2 o 4 tubi malpighiani.

L'apparato respiratorio degli eterotteri terrestri e semiacquatici è generalmente provvisto di 10 paia di stigmi, di cui 2 paia sono toracice e le altre disposte nella parte ventrale degli uriti I-VIII. Nelle forme acquatiche possono esserci modificazioni morfostrutturali che ne riducono il numero, ma quella più evidente si riscontra nei Nepidi, con il prolungamento dell'ultimo paio in due processi caudali detti sifoni.

L'apparato secretore è caratterizzato, nella maggior parte degli Eterotteri, dalla presenza delle citate ghiandole odorifere, che secernono una sostanza quasi sempre maleodorante, con effetto repellente. Nelle forme giovanili le ghiandole odorifere sono localizzate nell'addome e sboccano nella parte dorsale. Negli adulti sono invece disposte nel torace, presenti in numero di 2 o una, in quest'ultimo caso piuttosto sviluppata. I dotti efferenti, come si è detto, possono avere un unico sbocco (tipo omphalium) oppure due sbocchi latero-ventrali (tipo diastomico).

Biologia

Ovatura di Nezara viridula

Gli Eterotteri sono in generale insetti paurometaboli e lo sviluppo postembrionale passa attraverso due stadi di neanide e tre di ninfa. Si riproducono per anfigonia e sono ovipari. Le uova sono disposte isolate, o più spesso a gruppi, su vari supporti, in genere sulla superficie dei vegetali. Spesso sono parzialmente infisse nei tessuti vegetali oppure incollate con il secreto delle ghiandole colleteriche. Singolare è la deposizione delle uova in alcuni eterotteri acquatici (es. Belostomatidi), che vengono incollate sul dorso dei maschi. Lo scopo è quello di far svolgere l'incubazione in modo ottimale alternando l'immersione all'emersione in superficie per regolare l'afflusso di ossigeno e la temperatura.

L'alimentazione è generalmente saprofaga, zoofaga o fitofaga. Non sono rare l'onnivoria e il cannibalismo, che in genere rappresentano importanti fattori di regolazione delle popolazioni. Le forme zoofaghe sono ematofaghe oppure predatrici. Gli ematofagi fanno capo alle famiglie dei Cimicidi, dei Polictenidi e dei Reduvidi (sottofamiglia Triatominae) e attaccano mammiferi e uccelli. Alcune specie sono associate all'Uomo.

Le forme predatrici sono presenti in diverse famiglie e si nutrono, la maggior parte, a spese di piccoli artropodi, quali acari, tisanotteri, omotteri e uova di vari ordini. I predatori acquatici o acquaioli manifestano in generale una spiccata polifagia attaccando in generale vari invertebrati e, nel caso delle specie più grandi, anche piccoli vertebrati (girini e avannotti). La predazione si associa spesso a una spiccata aggressività, riscontrabile soprattutto fra i Reduvidi, i Nabidi e diversi eterotteri associati agli ambienti acquatici. Molte specie possono pungere anche l'Uomo quando vengono disturbate. Le specie predatrici di particolare interesse rientrano fra le famiglie dei Miridi, degli Antocoridi e degli Joppeicidi in quanto alcune sono impiegate in lotta biologica.

Gli eterotteri fitofagi di maggiore importanza fanno capo, in generale, alle famiglie dei Tingidi e dei Miridi e all'infraordine dei Pentatomomorfi. Rispetto agli Omotteri, la dannosità degli eterotteri è di secondaria importanza, sotto l'aspetto economico, tuttavia molte specie possono rivelarsi occasionalmente o frequentemente dannose alle coltivazioni. I danni consistono prevalentemente in cali della produttività delle piante, per sottrazione della linfa e per aborti fiorali, deprezzamento del prodotto per comparsa di aree decolorate o necrotiche più o meno estese, trasmissione di sapori e odori sgradevoli. Alcune specie, fra i Pentatomomorfi, sono possibili vettori di virus. Gli organi attaccati sono, secondo le specie, generalmente fiori, semi, frutti, foglie e giovani germogli. Fra gli altri regimi dietetici va citata la presenza di eterotteri micetofagi o sinfili.

Il pentatomide Palomena viridissima

L'habitat presenta una notevole varietà in relazione alle abitudini e all'alimentazione. Le specie terrestri, sia fitomize sia predatrici, vivono per lo più sui vegetali, con una propensione più o meno marcata per le forme arboree o per quelle erbacee. Altre specie vivono prevalentemente sul terreno o nelle lettiere forestali; in genere si tratta di specie saprofaghe oppure fitofagi che si alimentano a spese di semi caduti sul terreno o, infine, di predatori. Fra gli habitat terrestri si annoverano anche gli ambienti domestici per i Cimicomorfi ematofagi associati all'Uomo.

Alcuni

infraordini comprendono specie associate più o meno strettamente ad ambienti

acquatici oppure colonizzano ambienti in prossimità di specchi d'acqua di

varia natura. Queste specie possono essere distinte in due grandi gruppi:

- Specie prettamente acquatiche: le più importanti fanno capo all'infraordine

dei Nepomorfi. Vivono in acque dolci o salate, generalmente in acque

tranquille di laghi, stagni, paludi e fiumi a corso lento e la loro attività

si svolge in prevalenza in immersione. La loro morfologia è adattata a lunghe

immersioni perciò dispongono di strutture morfoanatomiche in grado di

sfruttare riserve d'aria o di attingere all'aria della superficie. Frequente

è la presenza di zampe natatorie.

- Specie acquaiole o semiacquatiche: le più importanti fanno capo all'infraordine dei Gerromorfi e dei Leptopodomorfi. Vivono generalmente nelle lettiere, sulle sponde o sulla vegetazione di ambienti acquatici oppure sulla stessa superficie dell'acqua. Sono capaci di brevi immersioni o molti, più in generale, di muoversi camminando o slittando sull'acqua sfruttando la tensione superficiale. Alcune specie hanno habitat marini.

Sistematica

La classificazione e l'inquadramento sistematico degli Eterotteri ha subito diverse modifiche. Originariamente erano inquadrati al livello di ordine con il nome di Hemiptera, poi esteso all'intero ordine che attualmente comprende anche gli Omotteri. La suddivisione interna su criteri morfologici, si è basata in passato su alcuni elementi che fondamentalmente ne definivano l'habitat, ma questa suddivisione è ormai superata ed è citata per lo più in alcuni vecchi testi di Entomologia applicata. La più ricorrente, attualmente, individua sette infraordini, a loro volta comprendenti una o più superfamiglie con oltre 70 famiglie. Non tutti gli autori concordano con la posizione sistematica di alcuni raggruppamenti, con divergenze che possono interessare l'inquadramento sistematico nell'ambito delle superfamiglie o delle famiglie e l'attribuzione del rango, a livello di famiglia o sottofamiglia. Tali divergenze sono dovute per lo più a informazioni ancora non soddisfacenti sulle relazioni filogenetiche.

Lo schema completo adottato in questa sede, si struttura secondo il seguente albero:

Infraordine:

Cimicomorpha. Comprende sei superfamiglie:

Cimicoidea. Famiglie: Anthocoridae, Cimicidae, Nabidae, Polyctenidae

Joppeicoidea. Famiglia: Joppeicidae

Miroidea. Famiglie: Microphysidae, Miridae

Reduvoidea o Reduvioidea. Famiglia: Reduviidae

Thaumastocoroidea. Famiglia: Thaumastocoridae

Tingoidea. Famiglia: Tingidae

Infraordine:

Dipsocoromorpha. Comprende una sola superfamiglia:

Dipsocoroidea. Famiglie: Ceratocombidae, Dipsocoridae, Schizopteridae

Infraordine:

Enicocephalomorpha. Comprende una sola superfamiglia:

Enicocephaloidea. Famiglia: Enicocephalidae

Infraordine:

Gerromorpha. Comprende quattro superfamiglie:

Gerroidea. Famiglie: Gerridae, Hermatobatidae, Veliidae

Hebroidea. Famiglia: Hebridae

Hydrometroidea. Famiglia: Hydrometridae, Macroveliidae, Paraphrynoveliidae

Mesovelioidea. Famiglia: Mesoveliidae

Infraordine:

Leptopodomorpha. Comprende due superfamiglie:

Leptopodoidea. Famiglie: Leptopodidae, Omaniidae

Saldoidea. Famiglie: Aepophilidae, Saldidae

Infraordine:

Nepomorpha. Comprende cinque superfamiglie:

Corixoidea. Famiglia: Corixidae

Gelastocoroidea. Famiglie: Gelastocoridae, Ochteridae

Naucoroidea. Famiglie: Aphelocheiridae, Naucoridae, Potamocoridae

Nepoidea. Famiglie: Belostomatidae, Nepidae

Notonectoidea. Famiglie: Helotrephidae, Notonectidae, Pleidae

Infraordine:

Pentatomomorpha. Comprende sei superfamiglie:

Aradoidea. Famiglie: Aradidae, Termitaphididae

Coreoidea. Famiglie: Alydidae, Coreidae, Hyocephalidae, Rhopalidae,

Stenocephalidae

Idiostoloidea. Famiglie: Henicocoridae, Idiostolidae

Lygaeoidea. Famiglie: Artheneidae, Berytidae, Blissidae, Colobathristidae,

Cryptorhamphidae, Cymidae, Geocoridae, Heterogastridae, Lygaeidae, Malcidae,

Ninidae, Oxycarenidae, Pachygronthidae, Piesmatidae, Rhyparochromidae

Pentatomoidea. Famiglie: Acanthosomatidae, Aphylidae, Canopidae, Cydnidae, Dinidoridae, Lestoniidae, Megarididae, Pentatomidae, Phloeidae, Plataspidae, Scutelleridae, Tessaratomidae, Thaumastellidae, Urostylidae

Pyrrhocoroidea. Famiglie: Largidae, Pyrrhocoridae.

Heteroptera is a group of about 40,000 species of insects in the Hemiptera. Sometimes called "true bugs", that name more commonly refers to Hemiptera as a whole, and "typical bugs" might be used as a more unequivocal alternative since among the Hemiptzera the heteropterans are most consistently and universally termed "bugs". "Heteroptera" is Greek for "different wings": most species have forewings with both membranous and hardened portions (called hemelytra); members of the primitive Enicocephalomorpha have wings that are completely membranous.

The name "Heteroptera" is used in two very different ways in modern classifications; in Linnean nomenclature it commonly appears as a suborder within the order Hemiptera, where it can be paraphyletic or monophyletic depending on its delimitation. In phylogenetic nomenclature it is used as an unranked clade within the Prosorrhyncha clade which in turn is in the Hemiptera clade. This results from the realization that the Coleorrhyncha are actually just a "living fossil" relative of the traditional Heteroptera, close enough to them to be actually united with that group. See below for a detailed discussion.

The Gerromorpha and Nepomorpha contain most of the aquatic and semi-aquatic members of the Heteroptera, while nearly all of the remaining groups that are common and familiar are in the Cimicomorpha and Pentatomomorpha.

Classification

The use of the name "Heteroptera" has a long history at the rank of order, dating back to Latreille, 1810, and it is only recently that it has been relegated to a subsidiary rank within a larger definition of Hemiptera, so many reference works still include it as an order. Whether to continue treating it as a suborder is still a subject of some controversy, as is whether the name itself should be used at all, though three basic approaches ranging from abolishing it entirely to maintaining the taxonomy with a slight change in systematics are proposed, two of which (but not the traditional one) agree with the phylogeny. The competing classifications basically boil down to preference for two suborders versus one when the "living fossil" family Peloridiidae is taken into consideration:

In the traditional classification, the Peloridiidae are retained as its own suborder, called Coleorrhyncha, and "Heteroptera" is treated as a suborder as well. Functionally, the only difference between this classification and the preceding is that the former uses the name Prosorrhyncha to refer to a particular clade, while the traditional approach divides this into the paraphyletic Heteroptera plus the monophyletic Coleorrhyncha: Many believe is preferable to use one name only, because they feel that the two traditional suborders are too closely related to be treated as separate and should instead be one suborder only.

In one revised classification proposed in 1995, the name of the suborder is Prosorrhyncha, and Heteroptera is a rankless subgroup within it. The only difference between Heteroptera and Prosorrhyncha is that the latter includes the family Peloridiidae, which is a tiny relictual group that is in its own monotypic superfamily and infraorder (if these totally rediundant ranks are used at all). In other words, the Heteroptera and Prosorrhyncha sensu Sorensen et al. are identical except that Prosorrhyncha contains one additional infraorder, called Peloridiomorpha (comprising only 13 small genera). The ongoing conflict between traditional, Linnaean classifications and non-traditional classifications is exemplified by the problem inherent in continued usage of the name Heteroptera when it no longer can be matched to any standard Linnaean rank (as it falls below suborder but above infraorder). If this classification wins out, then the "Heteroptera" grouping may be discarded in the near future, but in that case it is likely that no ranks are used at all according to the standards of phylogenetic nomenclature.

Alternatively, the modified approach of placing Coleorrhyncha within the Heteroptera can be used. Indeed, as that solution preserves the well-known Heteroptera at the taxonomic rank they traditionally hold while making them a good monophyletic group, it seems preferable to the paraphyletic "Heteroptera" used in older works. In that case, the "core" Heteroptera could be considered a section – as of yet unnamed, mainly because the Prosorrhyncha were proposed earlier – within the "expanded" Heteroptera, or the latter could simply be described as consisting of a basal "living fossil" lineage and a more apomorphic main radiation. Whether the name "Coleorrhyncha" is to be retained for the basal lineage or whether the more consistent "Peloridiomorpha" is used instead is a matter of taste, as described below.

Separate from the question of the actual "closeness" of Heteroptera and Coleorrhyncha is the potential disruption to traditional construction of names; there seems to be reluctance among hemipterists to abandon the use of "Heteroptera". This can be seen by the name itself, as it is a violation of convention to use the ending "-ptera" for any rank above genus other than an order - though since it is a convention rather than a mandatory rule of Linnean nomenclature, taxonomists are technically free to violate it (which is why, for example, not all insect orders end in "-ptera", e.g., Odonata). However, in most cases when such conventions are violated, it does not create an internal conflict as in the present case (that is, the order Hemiptera has a suborder named Heteroptera, which is an internal conflict). At least some hemipterists argue that the name Heteroptera should be dropped entirely to eliminate this internal conflict, though the third possibility offers a workaround. In that case, to achieve full consistency of names "Coleorrhyncha" would probably be dropped in favor of "Peloridiomorpha".

Selected families of Heteroptera

assassin

bugs (Reduviidae)

bedbugs and flower bugs (Cimicidae)

leaf bugs (c.6,000 species of Miridae)

leaf-footed bugs and squash bugs (Coreidae)

seed bugs (mainly Lygaeidae and Rhyparochromidae)

stink bugs or shield bugs (Pentatomidae and related families)

Waterbugs

"Waterbugs" is a common name for a number of aquatic insects, most of which are classified in the infraorders Gerromorpha and Nepomorpha of the order Hemiptera. The latter infraorder contains those taxa that were once known as the "Gymnocerata". Note that the term "water bug" is very often applied to some cockroaches, which are not true bugs and as Dictyoptera not even close to them (true bugs are Paraneoptera).

Selected families of water bugs

back

swimmers (Notonectidae)

giant water bugs (Belostomatidae)

water scorpions (Nepidae)

water boatmen (Corixidae)

pond skaters (Gerridae)

Smaller water strider (Veliidae)

Gonocerus acuteangulatus

I Coreidi (Coreidae Leach, 1815) sono una famiglia di insetti Pentatomomorfi dell'ordine Rhynchota Heteroptera, superfamiglia Coreoidea, diffusa in tutto il mondo. Costituiscono, per importanza e numero di specie, il raggruppamento più rappresentativo della superfamiglia.

La famiglia si presenta morfologicamente eterogenea sia pure con alcuni caratteri ricorrenti. Il corpo è di dimensioni medie o grandi, fino ad alcuni cm di lunghezza, con profilo variabile da ovale a quadrangolare, più o meno oblungo, talvolta con caratteristiche conformazioni delle zampe. Il tegumento ha colorazioni uniformi, in genere su tonalità brunastre più o meno scure, talvolta con caratteristiche bande trasversali sulle emielitre. Meno frequenti sono invece le livree variopinte, con colori e disegni più o meno vistosi, come avviene, ad esempio, nei generi Anisoscelis e Diactor, in cui sono comprese anche specie di particolare bellezza.

Il capo è relativamente piccolo, nettamente più stretto del protorace, provvisto di due ocelli e con antenne e rostro composti da quattro segmenti. Nel torace, il pronoto è subtrapezoidale, con margine posteriore generalmente ricurvo, di larghezza 2-3 volte superiore a quella del capo. Il mesoscutello è relativamente piccolo e generalmente più largo del capo. Le emielitre hanno la membrana percorsa da una fitta nervatura. Le zampe posteriori hanno in genere i femori relativamente spessi e robusti e in molte specie le tibie sono marcatamente appiattite; femori e tibie possono presentare processi di varia forma, conferendo talvolta un aspetto bizzarro. L'appiattimento delle tibie posteriori, ricorrente in molti Coreidi, giustifica il nome leaf-footed bug dato dagli anglosassoni a queste cimici.

L'addome presenta i laterotergiti appiattiti, talvolta espansi lateralmente oltre le emielitre, carattere piuttosto frequente in diversi Pentatomomorfi. Sono presenti due tricobotri ventrali nel III urite e tre negli uriti dal III al VII.

Anisocelis flavolineata

I Coreidi sono in generale insetti fitofagi, ma diverse fonti citano anche la presenza di un numero non precisato di predatori. La fitofagia si esprime nella maggior parte delle specie sotto forma di polifagia, ma sono citate relazioni più specifiche di alcuni taxa con determinati raggruppamenti sistematici di piante. Rispetto al numero di specie, l'importanza agraria di questa famiglia è contenuta, tuttavia fra i Coreidi si annoverano anche specie dannose ad alcune colture.

In Italia la specie di maggiore interesse è la cimice del nocciolo (Gonocerus acuteangulatus): pur essendo polifago, in Sicilia è uno dei più frequenti e dannosi agenti del cimiciato delle nocciole e dell'aborto traumatico. Le stesse affezioni possono essere causate sul pistacchio. Può inoltre essere vettore del fungo Nematospora coryli, agente eziologico della stigmatomicosi del nocciolo. Le femmine depongono le uova isolate sulle piante. In alcune specie sono invece portate dai maschi sul dorso o sul ventre.

Molti Eterotteri sono noti per l'odore sgradevole dovuto al secreto delle ghiandole odorifere metatoraciche, ma fra i Coreidi va citata una curiosa eccezione: il Coreus marginatus, specie presente nell'Europa centrale, emana infatti un profumo di mela. La famiglia è cosmopolita, con una larga diffusione in tutte le principali regioni zoogeografiche del mondo.

Coreus marginatus

La famiglia è la più ricca fra i Coreoidei: comprende circa 250 generi con circa 1800 specie, ma alcune fonti citano anche fino a 2000 specie. La tassonomia interna della famiglia maggiormente condivisa vede la suddivisione in tre sottofamiglie:

Coreinae

Meropachyinae

Pseudophloeinae

Piuttosto controversa è invece la suddivisione delle sottofamiglie in tribù. Coreinae e Pseudophloeinae hanno una larga distribuzione geografica, mentre la diffusione dei Meropachyinae è limitata alla regione neotropicale.