Lessico

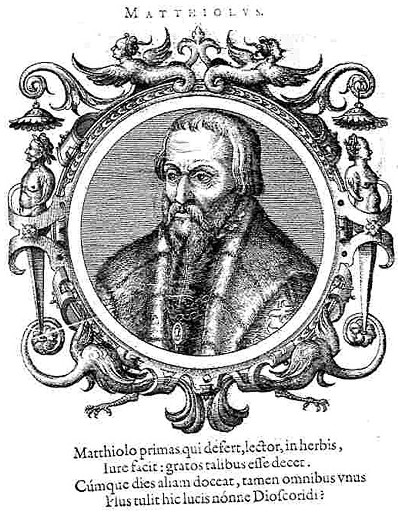

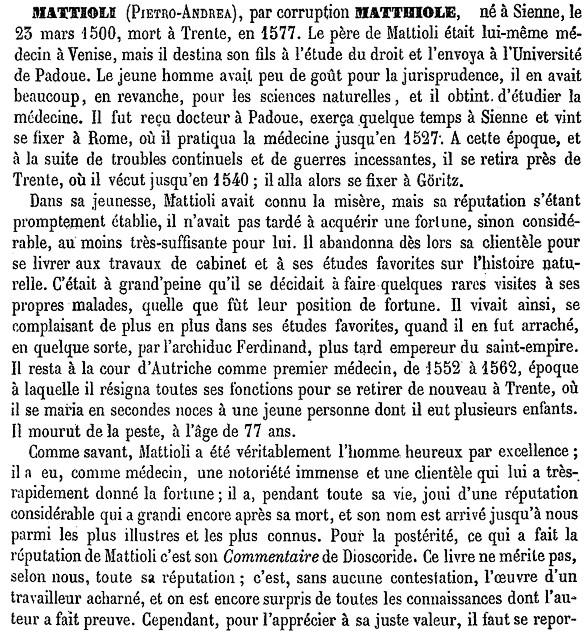

Pierandrea Mattioli

incisione

di Theodor de Bry (1528-1598)

da Bibliotheca chalcographica di Jean-Jacques Boissard - 1669

Naturalista e medico (Siena 1500 - Trento 1577). Altre fonti danno rispettivamente 1501 e 1578. Nasce a Siena nel 1500 da Francesco Mattioli, medico, e da Lucrezia Buoninsegna. Si trasferisce col padre a Venezia e nel 1523 si laurea a Padova in medicina. Rientrato a Siena alla morte del padre, se ne allontana poco dopo a causa degli scontri tra le diverse fazioni, per recarsi a Perugia che lascia, dopo la specializzazione in chirurgia, per raggiungere Roma dove si ferma fino al 1527, anno del sacco.

Nel 1527

si sposta a Trento, divenendo medico personale del Principe Vescovo Bernardo

di Clès![]() .

Al potente protettore dedica il trattato De morbo gallico e il poema in

versi Il Magno Palazzo del Cardinale di Trento, pubblicato nel 1539.

Quest’opera costituisce un documento di grande importanza, perché fornisce

preziose informazioni sul nuovo aspetto assunto dal Castello del Buonconsiglio

dopo gli interventi architettonici voluti da Bernardo di Clès. Mattioli si

trattiene in Trentino per circa un trentennio, durante il quale soggiorna

soprattutto in Val di Non (in provincia di Trento, detta anche Valle Anania

.

Al potente protettore dedica il trattato De morbo gallico e il poema in

versi Il Magno Palazzo del Cardinale di Trento, pubblicato nel 1539.

Quest’opera costituisce un documento di grande importanza, perché fornisce

preziose informazioni sul nuovo aspetto assunto dal Castello del Buonconsiglio

dopo gli interventi architettonici voluti da Bernardo di Clès. Mattioli si

trattiene in Trentino per circa un trentennio, durante il quale soggiorna

soprattutto in Val di Non (in provincia di Trento, detta anche Valle Anania![]() o

Anaunia), nei dintorni di Trento e sul monte Baldo.

o

Anaunia), nei dintorni di Trento e sul monte Baldo.

In queste zone di montagna ha modo di dedicarsi alla botanica, sua grande passione e di venire in contatto con conoscenze e tradizioni popolari che forniranno la base delle sue ricerche sulle proprietà terapeutiche delle piante.

Nel 1539,

forse a seguito della morte del Principe Vescovo Bernardo, parte alla volta di

Gorizia e, in seguito, di Praga. Nel 1544 pubblica a Venezia il suo lavoro di

botanica Discorsi redatto

in italiano e nel 1554 pubblica sempre a Venezia, ma in latino,

l’equivalente opera a carattere naturalistico e terapeutico che lo rese

celebre: Commentarii in libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei De Medica

Materia![]() (Venetiis, apud Valgrisium, 1554) e che dominò il sapere botanico

per due secoli, con 61 edizioni e con traduzione in 5 lingue.

(Venetiis, apud Valgrisium, 1554) e che dominò il sapere botanico

per due secoli, con 61 edizioni e con traduzione in 5 lingue.

La prima

traduzione in italiano dei Commentarii vide anch’essa la luce a

Venezia nel 1557 ad opera di

Valgrisi. Pierandrea Mattioli raggiunge l’apice della sua carriera nel 1555,

quando Ferdinando I d’Austria![]() lo chiama a corte come medico personale del suo secondogenito e rimane a

servizio degli Asburgo (anche di Massimiliano II

lo chiama a corte come medico personale del suo secondogenito e rimane a

servizio degli Asburgo (anche di Massimiliano II![]() ,

primogenito di Ferdinando I e suo successore nel 1564)

fino al 1571, anno in cui decide di far ritorno a Trento, dove rimane

fino alla morte nel 1577 dovuta alla peste

,

primogenito di Ferdinando I e suo successore nel 1564)

fino al 1571, anno in cui decide di far ritorno a Trento, dove rimane

fino alla morte nel 1577 dovuta alla peste![]() e

viene sepolto nella cattedrale di San Vigilio

e

viene sepolto nella cattedrale di San Vigilio![]() , dove gli viene eretto

un sepolcro marmoreo che lo raffigura al suo tavolo da lavoro.

, dove gli viene eretto

un sepolcro marmoreo che lo raffigura al suo tavolo da lavoro.

Per i suoi meriti Charles Plumier![]() , valoroso botanico di Marsiglia

(1646-1706), gli dedicò il genere Matthiola

, valoroso botanico di Marsiglia

(1646-1706), gli dedicò il genere Matthiola![]() . La sua pietra tombale è conservata all’ingresso

del Duomo di Trento.

. La sua pietra tombale è conservata all’ingresso

del Duomo di Trento.

da www.buoncosiglio.it - con alcune modifiche e aggiunte

Pietro Andrea Mattioli

Pietro

Andrea Mattioli (Siena, 12 marzo 1501 – Trento, 1578) è stato un umanista e

medico italiano. Pietro (Pier) Andrea Mattioli (Matthioli) nasce a Siena nel

1501 (1500 ab incarnatione![]() ), ma

passa la sua infanzia a Venezia, dove il padre, Francesco, esercita la

professione di medico. Appena sufficientemente grande, il padre lo manda a

Padova dove inizia a studiare varie materie, tipiche dell'epoca, come il

latino, il greco antico, la retorica e la filosofia. Tuttavia Pietro Andrea si

appassiona più che a tutte alla medicina, e proprio in questa materia si

laurea nel 1523. Quando il padre muore, torna tuttavia a Siena ma la città è

sconvolta da una faida tra famiglie rivali per cui decide di recarsi a Perugia

per studiare chirurgia sotto il maestro Gregorio Caravita.

), ma

passa la sua infanzia a Venezia, dove il padre, Francesco, esercita la

professione di medico. Appena sufficientemente grande, il padre lo manda a

Padova dove inizia a studiare varie materie, tipiche dell'epoca, come il

latino, il greco antico, la retorica e la filosofia. Tuttavia Pietro Andrea si

appassiona più che a tutte alla medicina, e proprio in questa materia si

laurea nel 1523. Quando il padre muore, torna tuttavia a Siena ma la città è

sconvolta da una faida tra famiglie rivali per cui decide di recarsi a Perugia

per studiare chirurgia sotto il maestro Gregorio Caravita.

Da lì si

trasferisce a Roma dove continua i suoi studi medici presso l' Ospedale di

Santo Spirito e lo Xenodochium San Giacomo per gli incurabili, ma nel 1527, a

causa del sacco dei Lanzichenecchi, decide di lasciare la città per

trasferirsi a Trento dove rimane per un trentennio. Va quindi a vivere in Val

di Non e presto la sua fama giunge alle orecchie del principe-vescovo Bernardo

Clesio![]() che lo

invita presso il castello del Buonconsiglio offrendogli il posto di

consigliere e medico personale. Proprio al vescovo Clesio, Mattioli dedicherà

due delle sue prime opere, una delle quali, il poema in versi «Il Magno

Palazzo del Cardinale di Trento», descrive in dettaglio la ristrutturazione

di carattere rinascimentale che il vescovo ordinò per il suo castello. Il

poema, pubblicato nel 1539 dal Marcolini a Venezia, utilizza una struttura

detta dell'ottava rima, come quella che usava il Boccaccio

che lo

invita presso il castello del Buonconsiglio offrendogli il posto di

consigliere e medico personale. Proprio al vescovo Clesio, Mattioli dedicherà

due delle sue prime opere, una delle quali, il poema in versi «Il Magno

Palazzo del Cardinale di Trento», descrive in dettaglio la ristrutturazione

di carattere rinascimentale che il vescovo ordinò per il suo castello. Il

poema, pubblicato nel 1539 dal Marcolini a Venezia, utilizza una struttura

detta dell'ottava rima, come quella che usava il Boccaccio![]() , ma non

è opera dello stesso livello di quelle di altri poeti dell'epoca.

, ma non

è opera dello stesso livello di quelle di altri poeti dell'epoca.

Nel 1528

Mattioli sposa una donna trentina, una tal Elisabetta di cui non è noto il

cognome, e dalla quale ha un figlio. Cinque anni dopo pubblica il suo primo

libello: «Morbi Gallici Novum ac Utilissimum Opusculum» e inizia a lavorare

alla sua opera su Dioscoride![]() . Poi nel

1536 Mattioli accompagna Bernardo Clesio a Napoli per un incontro con

l'imperatore Carlo V. Quando tuttavia Bernardo Clesio muore, nel 1539, gli

succede Cristoforo Madruzzo il quale ha già un medico, e così Mattioli si

trasferisce a Cles, dove tuttavia si trova presto in ristrettezze finanziarie.

. Poi nel

1536 Mattioli accompagna Bernardo Clesio a Napoli per un incontro con

l'imperatore Carlo V. Quando tuttavia Bernardo Clesio muore, nel 1539, gli

succede Cristoforo Madruzzo il quale ha già un medico, e così Mattioli si

trasferisce a Cles, dove tuttavia si trova presto in ristrettezze finanziarie.

Tra il 1541 e il 1542 Mattioli si trasferisce a Gorizia, dove pratica la professione di medico e lavora alla traduzione della Materia Medica di Dioscoride dal greco, aggiungendovi i suoi discorsi e commenti. Poi finalmente nel 1544 pubblica per la prima volta la sua opera principale, «Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo Libri cinque Della historia, et materia medicinale tradotti in lingua volgare italiana da M. Pietro Andrea Matthiolo Sanese Medico, con amplissimi discorsi, et comenti, et dottissime annotationi, et censure del medesimo interprete», più comunemente conosciuto come i «Discorsi di Pier Andrea Mattioli» sull'opera di Dioscoride. La prima stesura fu pubblicata a Venezia senza le figure e fu dedicata al cardinale Cristoforo Madruzzo, principe-vescovo di Trento e Bressanone.

Da notare che Mattioli non si limita a tradurre l'opera di Dioscoride, ma la completa con i risultati di una serie di ricerche su piante ancora sconosciute all'epoca, trasformando i Discorsi in un'opera fondamentale sulle piante medicinali, un vero punto di riferimento per scienziati e medici per diversi secoli.

Nel 1548

pubblica la seconda edizione dei «Discorsi di Mattioli su Dioscoride», con

l'aggiunta del sesto libro sui rimedi contro i veleni, considerato apocrifo da

molti. In seguito vengono pubblicate molte altre edizioni, alcune tuttavia

senza la sua approvazione. Riceve anche molte critiche da notabili dell'epoca.

Nel 1554 viene pubblicata la prima edizione latina dei Discorsi di

Mattioli, chiamata anche Commentarii, ovvero «Petri Andreae Matthioli

Medici Senensis Commentarii, in Libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei, de

Materia Medica, Adjectis quàm plurimis plantarum & animalium imaginibus,

eodem authore»![]() . È la

prima edizione a essere illustrata ed è dedicata a Ferdinando I d'Austria

. È la

prima edizione a essere illustrata ed è dedicata a Ferdinando I d'Austria![]() ,

allora Principe dei Romani, di Pannonia e di Boemia, infante di Spagna,

arciduca d'Austra, duca di Borgogna, conte e signore del Tirolo. In seguito

sarà tradotta anche in ceco (1562), tedesco (1563) e Francese.

,

allora Principe dei Romani, di Pannonia e di Boemia, infante di Spagna,

arciduca d'Austra, duca di Borgogna, conte e signore del Tirolo. In seguito

sarà tradotta anche in ceco (1562), tedesco (1563) e Francese.

In seguito a tanta fama e successo, Ferdinando I chiama Mattioli a Praga come medico personale del suo secondogenito arciduca Ferdinando. Prima di partire, tuttavia, gli abitanti di Gorizia decidono di donagli una preziosa catena d'oro che si può vedere in molte delle sue raffigurazioni, come segno di stima e affetto. Nonostante questo, nel 1555 Mattioli si trasferisce a Praga, anche se già l'anno successivo è costretto a seguire, suo malgrado, l'arciduca Ferdinando in Ungheria nella guerra contro i Turchi.

Nel 1557

si sposa per la seconda volta con una nobile goriziana, Girolama di Varmo

dalla quale ha due figli, Ferdinando nel 1562 e Massimiliano nel 1568, i cui

nomi sono scelti chiaramente in onore della casa reale. Proprio il 13 luglio

1562 Mattioli viene nominato da Ferdinando Consigliere Aulico e nobile del

Sacro Romano Impero. Quando Ferdinando muore nel 1564 sale al trono

Massimiliano II![]() . Per un po' Mattioli resta al servizio del nuovo sovrano, ma

nel 1571 decide di ritirarsi definitivamente a Trento. Due anni prima si era

sposato per la terza volta, di nuovo con una donna trentina, una tale Susanna

Caerubina.

. Per un po' Mattioli resta al servizio del nuovo sovrano, ma

nel 1571 decide di ritirarsi definitivamente a Trento. Due anni prima si era

sposato per la terza volta, di nuovo con una donna trentina, una tale Susanna

Caerubina.

Nel 1578

(1577 ab incarnatione) Pietro Andrea Mattioli muore di peste![]() a Trento

nel mese di gennaio o di febbraio. I figli Ferdinando e Massimiliano gli

dedicano un magnifico monumento funebre che pongono nel Duomo della città,

tuttora esistente.

a Trento

nel mese di gennaio o di febbraio. I figli Ferdinando e Massimiliano gli

dedicano un magnifico monumento funebre che pongono nel Duomo della città,

tuttora esistente.

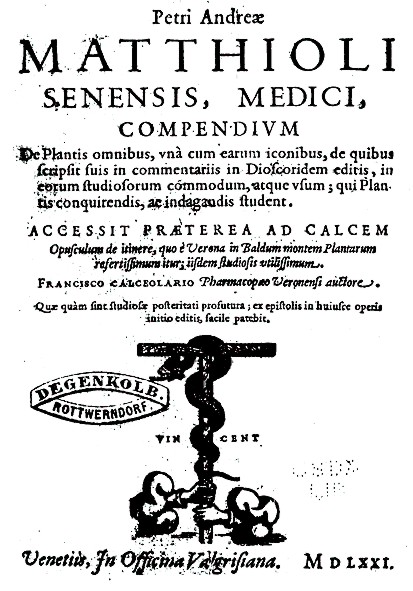

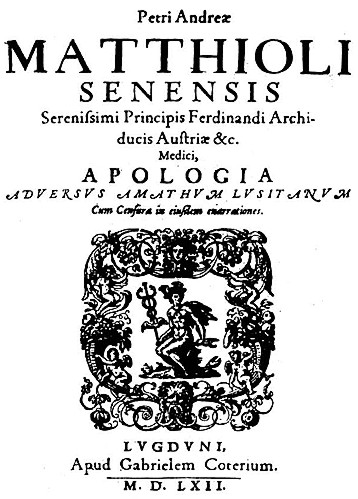

Opere

1533,

Morbi Gallici Novum ac Utilissimum Opusculum

1535, Liber de Morbo Gallico, dedicato a Bernardo Clesio

1536, De Morbi Gallici Curandi Ratione

1539, Il Magno Palazzo del Cardinale di Trento

1544, Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo Libri cinque Della historia, et materia

medicinale tradotti in lingua volgare italiana da M. Pietro Andrea Matthiolo

Sanese Medico, con amplissimi discorsi, et comenti, et dottissime annotationi,

et censure del medesimo interprete, detti Discorsi

1548, Traduzione in italiano della Geografia di Tolomeo

1554, Petri Andreae Matthioli Medici Senensis Commentarii, in Libros sex

Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei, de Materia Medica, Adjectis quàm plurimis

plantarum & animalium imaginibus, eodem authore, detti Commentarii

1558, Apologia Adversus Amatum Lusitanum![]()

1561, Epistolarum Medicinalium Libri Quinque

1569, Opusculum de Simplicium Medicamentorum Facultatibus

1571, Compendium de Plantis Omnibus una cum Earum Iconibus

A

quell'epoca, nel Senese e nel Fiorentino, si utilizzava un calendario diverso

da quello usato attualmente e che inizia con il primo di gennaio. Quello

senese e fiorentino, infatti, iniziava il 25 marzo, ovvero il giorno

dell'Annunciazione a Maria. Tutte le date erano quindi un anno indietro tra il

1º gennaio e il 24 marzo. Questo modo di contare gli anni si chiamava "ab

incarnatione" e poiché Mattioli nacque e morì proprio nei primi mesi

dell'anno, ne derivano due date diverse sia per la sua data di nascita che per

quella di morte, a seconda del calendario considerato. Mentre infatti per il

calendario gregoriano il 1501 va dal gennaio 1501 al dicembre 1501, per quello

senese e fiorentino i primi tre mesi dell'anno, ovvero dal primo gennaio al 24

marzo, si è ancora nel 1500. Bisogna quindi fare attenzione allo stile delle

date per quanto riguarda la biografia di Mattioli come quella di altri

personaggi dello stesso periodo, anche perché papa Gregorio XIII![]() riformò il

calendario nel 1582 saltando 10 giorni in ottobre ma i domini fiorentini si

allinearono al nuovo calendario solo a partire dal 1750.

riformò il

calendario nel 1582 saltando 10 giorni in ottobre ma i domini fiorentini si

allinearono al nuovo calendario solo a partire dal 1750.

Valle

Anania

Valle Anaunia - Val di Non

Pierandrea

Mattioli a proposito dell'agarico![]() usa l'aggettivo latino Ananiensis per indicare i monti della Val di

Non: ipse quidem saepius in Ananiensibus montibus praestantissimum agaricum

parva quadam securi a laricibus quam pluribus deieci. Nella biografia di

Mattioli stilata da Girolamo Tiraboschi (Storia della letteratura italiana

1796) leggiamo che "quattordici anni era il Mattioli vissuto nella Valle

Anania nel distretto di Trento"

usa l'aggettivo latino Ananiensis per indicare i monti della Val di

Non: ipse quidem saepius in Ananiensibus montibus praestantissimum agaricum

parva quadam securi a laricibus quam pluribus deieci. Nella biografia di

Mattioli stilata da Girolamo Tiraboschi (Storia della letteratura italiana

1796) leggiamo che "quattordici anni era il Mattioli vissuto nella Valle

Anania nel distretto di Trento"![]() .

Oggi Anania è irreperibile sia nelle enciclopedie che nel web. Al suo posto

troviamo Anaunia. Anaunia deriva dal nome dell’antico capoluogo Anagnia,

oggi Sanzeno, 39 km a nord di Trento.

.

Oggi Anania è irreperibile sia nelle enciclopedie che nel web. Al suo posto

troviamo Anaunia. Anaunia deriva dal nome dell’antico capoluogo Anagnia,

oggi Sanzeno, 39 km a nord di Trento.

Anaunia regio imperii Romani in Alpibus erat. Haec regio habebat duas valles quae recentibus temporibus sermo Italianus Val di Non et Val di Sole, Germanicus autem Nonstal sive Nonsberg et Sulzberg appellat. – web

Val di Non

La Val di Non è una delle principali valli del Trentino, situata nella parte nord-occidentale della provincia. È costituita da un ampio altopiano, attraversato dal torrente Noce e conta 38 comuni. Orograficamente la valle si biforca a Y all'altezza del lago di Santa Giustina e quindi la zona si divide in sponda destra (a ovest del Noce), sponda sinistra (d est del fiume) e "terza sponda" (la zona a nord del Noce e del rio Novella).

La Val di Non ha 38 comuni

1 Castelfondo - 2 Fondo - 3 Malosco - 4 Brez - 5 Sarnonico - 6 Ronzone - 7 Ruffrè-Mendola - 8 Cavareno - 9 Amblar - 10 Romeno - 11 Don - 12 Rumo - 13 Bresimo - 14 Cis – 15 Livo - 16 Cagnò - 17 Revò - 18 Romallo - 19 Dambel - 20 Cloz - 21 Sanzeno - 22 Cles - 23 Coredo - 24 Smarano - 25 Sfruz - 26 Vervò - 27 Tassullo - 28 Tuenno - 29 Terres - 30 Nanno – 31 Taio - 32 Tres - 33 Ton - 34 Sporminore - 35 Denno - 36 Cunevo - 37 Flavon - 38 Campodenno

La valle si apre a occidente della Valle dell'Adige, all'altezza della confluenza del Noce nell'Adige. Deve il suo nome ai Monti Anauni che la separano dalla Bassa Atesina e dalla Val d'Adige. In tempi remoti era infatti chiamata Valle Anaune e nel corso dei secoli mutò il suo nome in Val di Non grazie alla lingua dialettale dei suoi abitanti, il Nones, secondo alcuni linguisti di derivazione ladina. A occidente è delimitata dalle Dolomiti di Brenta, mentre a nord-ovest, dove nasce la Val di Sole, dalla Catena delle Maddalene; confina infine a settentrione con la Val d'Ultimo e l'Alto Adige.

La valle è raggiungibile, oltre che dall'accesso principale costituto dalla strada statale 43 che la collega con Mezzolombardo e la Valle dell'Adige attraverso la Forra della Rocchetta, da altri 3 passi: il Passo Palade da Merano, il Passo della Mendola da Caldaro e Bolzano, infine il Ponte di Mostizzolo che la collega a est con la Val di Sole, da cui per il Passo del Tonale si passa in Lombardia. È inoltre attraversata dalla Ferrovia Trento-Malè.

Il centro

abitato più importante della vallata è Cles, che sorge a lato del grande

lago artificiale di Santa Giustina. La valle è ricca di storia, dal tempo

degli antichi romani che avevano intuito l'importanza di questi territori

vicini al Passo del Brennero, fino al Medioevo, periodo in cui sorgono

numerosi castelli, come Castel Thun, Castel Bragher, Castel Coredo, Castel

Cles oppure come il Santuario di San Romedio![]() ,

o i palazzi assessorili di Cles e Coredo, che divennero i centri

giuridico-amministrativi più importanti del periodo, in cui sono state emesse

anche sentenze di condanna a morte nel periodo di caccia alle streghe. In

valle sono presenti numerosi laghi, come il lago artificiale di Santa Giustina

e i laghi di Coredo e Tavon e di Tovel, segno dell'abbondanza di acqua della

zona.

,

o i palazzi assessorili di Cles e Coredo, che divennero i centri

giuridico-amministrativi più importanti del periodo, in cui sono state emesse

anche sentenze di condanna a morte nel periodo di caccia alle streghe. In

valle sono presenti numerosi laghi, come il lago artificiale di Santa Giustina

e i laghi di Coredo e Tavon e di Tovel, segno dell'abbondanza di acqua della

zona.

L'economia della vallata è principalmente di tipo agricolo (frutticolo): la valle è resa famosa dalla vastissima produzione delle mele Golden conosciute commercialmente con il marchio Melinda (primo marchio DOP concesso per un prodotto del settore frutticolo). Ricoprono una discreta importanza per l'economia locale anche il turismo e l'artigianato, sono inoltre presenti alcune aree artigianali e con piccole industrie e cementifici nella zona di Cles, Tassullo e Mollaro. Nell'alta valle di Non sono anche presenti piccole imprese legate all'industria del legno che producono imballaggi.

Percorsi d'Anaunia

La particolare configurazione del territorio della Valle di Non, con ampi terrazzi morenici incisi dalle profonde forre dei Torrenti Noce e Novella, distingue - da un punto di vista geomorfologico - tre distinte zone localmente definite come sponda sinistra, sponda destra e terza sponda: quella in sinistra orografica del Torrente Noce, dalla gola della Rocchetta a sud, fino al Passo delle Palade a nord, comprendente l’ampio territorio dominato dalla lunga e boscosa catena del Monte Roen è storicamente individuata come Anaunia dal nome dell’antico capoluogo Anagnia (Sanzeno); tale zona è citata nell’importante documento storico risalente al 46 dC rinvenuto a Cles (Tavola Clesiana), con il quale l’imperatore Claudio concedeva la cittadinanza romana agli abitanti della valle, distinguendoli in Anauni, Tuliassi e Sinduni, probabilmente in funzione della loro collocazione geografica.

L’Anaunia

è a sua volta divisa dalla profonda forra del Torrente San Romedio che ne

delimita la parte nord (Alta Anaunia o, in gergo popolare locale, “Soratovo”).

Beneficiando della notevole ricchezza di beni storici (castelli, torri,

viabilità antica etc.) e ambientali (forre, grotte, punti panoramici,

vegetazione etc.), presenti in questo ambito geografico, sono stati ideati e

proposti i seguenti 12 percorsi di tipo turistico-escursionistico, finalizzati

al collegamento e alla riscoperta di tali luoghi. L’asse principale di

collegamento, dalla Rocchetta a San Romedio![]() ,

costituito dai percorsi n. 1-4-5-6-8-12 si sviluppa per circa 20 km, partendo

dai ruderi della Torre di Visione (castello medioevale con amplissimo

panorama) sovrastante la gola della Rocchetta, arrivando fino alla pineta

oltre l’abitato di Smarano a ridosso della Valle del Verdès in fondo alla

quale sorge il famoso santuario, raggiungibile tramite sentiero che,

dipartendosi dal percorso n. 12, scende al lago di Tavon e successivamente a

San Romedio.

,

costituito dai percorsi n. 1-4-5-6-8-12 si sviluppa per circa 20 km, partendo

dai ruderi della Torre di Visione (castello medioevale con amplissimo

panorama) sovrastante la gola della Rocchetta, arrivando fino alla pineta

oltre l’abitato di Smarano a ridosso della Valle del Verdès in fondo alla

quale sorge il famoso santuario, raggiungibile tramite sentiero che,

dipartendosi dal percorso n. 12, scende al lago di Tavon e successivamente a

San Romedio.

Tale sistema di percorsi recupera la viabilità antica che dalla Rocchetta giunge a Castel Thun e in seguito al notevole complesso edilizio - religioso di San Martino a Vervò, attraverso bei boschi di faggio e conifere, passando per la guarnigione di Prà Ciastel (ruderi, probabile luogo di sosta e cambio dei cavalli), Mas del Mont (ampia e panoramica distesa prativa) e attraversando la forra del Rio Pongaiola; successivamente il percorso prosegue a monte dell’abitato di Vervò riprendendo comode strade forestali, fino agli abitati di Sfruz e Smarano, dopo aver attraversato la valletta del rio di Sette Fontane. Anche quest’ ultimo tratto di percorso rappresenta probabilmente l’antica viabilità di collegamento fra gli abitati di Vervò e Tres con Smarano e Sfruz, separati dal solco vallivo del rio Sette Fontane.

Dall’itinerario principale si dipartono dei tracciati (per altri 25 km complessivi, finalizzati al raggiungimento di manufatti e luoghi di particolare interesse: in prossimità di Vigo d’Anaunia, tramite i percorsi n. 2 e 3, rispettivamente il castel S.Pietro (XII sec. su sperone roccioso lungo l’antica via che collegava la Val d’Adige) e la forra della Val Ciucina; a valle di Priò, l’agevole e lungo percorso n. 7, da Priò a Castel Bragher (XIII sec.), transitando per l’abitato di Vion; a Tres, i percorsi n. 9 e 10 passando per il “Lac del Bosc” (bella conca prativa con biotopo lacustre) o raggiungere il singolare anfratto roccioso “Vout Sette Fontane”, con possibilità di proseguire per Sfruz o Smarano; da questi, il sistema di percorsi è collegato verso monte con il panoramico altopiano della Predaia (percorsi n. 8 e 11) e - tramite la strada esistente che sale all’omonimo rifugio, con la sentieristica CAI che corre in quota lungo la dorsale della Catena del Monte Roen (Sentiero Italia), raggiungibile anche dal versante atesino (Mezzocorona, Favogna e Termeno).

www.percorsianaunia.it

Scrigno di spiritualità e suggestione

Attraverso una passeggiata panoramica lungo fitti boschi e anfratti rocciosi, sospesi sopra le acque che scorrono nel fondo valle, si giunge alla splendida cornice del Santuario di San Romedio. Una ripida scalinata di 131 gradini conduce il visitatore, attraverso un complesso di piccolissime chiesette sovrapposte, sulla sommità dello scoglio roccioso, alto più di settanta metri, dove, secondo la leggenda, si sarebbe rifugiato in eremitaggio San Romedio.

Si narra di come, sul finire del X secolo, il nobile Romedio, erede della prestigiosa casata tirolese dei Thaur, chiamato dalla voce di Dio, abbandonate tutte le sue ricchezze, decise di cercare la vera felicità e la comunione col Creatore ritirandosi in meditazione sulla cima di una roccia. Alla sua morte, coloro che gli erano stati fedeli, scavarono nella roccia la sua tomba e diedero vita al culto che dal lontano anno 1000 si perpetua ancor oggi.

A partire dalla prima cappella costruita nell'XI secolo, la fede degli umili nel loro Santo protettore fece sì che venissero erette, nel corso dei secoli, una sopra le altre, tre piccole chiesette, due cappelle e sette edicole della Passione, vere custodi della sacralità e della magia del santuario. La fede nel Santo in Valle era davvero forte, tanto che a partire dal XV secolo le pareti lungo la scalinata che conduce alla tomba dell'eremita si riempirono di oggetti ex-voto, segni dell'immensa fiducia dei pellegrini nel potere del Santo.

Il Santuario di San Romedio, uno dei più suggestivi in Europa, spesso ricordato anche per l'area faunistica adiacente l'ingresso in cui vivono in semilibertà due orsi, vera mascotte di tutti i bambini della Val di Non. La loro presenza in questo luogo di culto è¨ legata alla leggenda secondo cui Romedio, ormai vecchio, si sarebbe incamminato verso la città deciso a incontrare il Vescovo di Trento Vigilio. Lungo il percorso il suo cavallo sarebbe stato sbranato da un orso, Romedio tuttavia non si diede per vinto e avvicinatosi alla bestia sarebbe riuscito miracolosamente a renderla mansueta e a cavalcarla fino a Trento. Il 15 gennaio di ogni anno si festeggia il giorno di San Romedio con una messa e il tradizionale piatto del pellegrino a base di trippe.

www.valledinon.tn.it

Sulle orme di Pierandrea Mattioli

un piovoso 12 agosto 2006

foto

di Claudia Mattioli e Simone Savastano![]()

Nel

centro della città, in piazza del Duomo, sorge la cattedrale di San Vigilio![]() ,

costruzione romanico-gotica di derivazione lombarda dei secoli XII-XIV, con

aggiunte successive. Vi si tennero tutte le sedute formali del Concilio

Tridentino, dal dicembre 1545 al dicembre 1563.

,

costruzione romanico-gotica di derivazione lombarda dei secoli XII-XIV, con

aggiunte successive. Vi si tennero tutte le sedute formali del Concilio

Tridentino, dal dicembre 1545 al dicembre 1563.

Pierandrea Mattioli sta stilando il suo commento a Dioscoride

Vescovo e patrono della città di Trento, visse nella seconda metà del IV secolo. Le notizie che abbiamo mescolano dati storicamente documentati ad altri di origine leggendaria, come probabilmente il martirio, avvenuto secondo la tradizione a opera delle popolazioni pagane trentine della Val Rendena. Recatosi in quelle zone con l’intento di convertirle, il vescovo Vigilio vi avrebbe trovato la morte per lapidazione. Una diffusa iconografia popolare, affermatasi in tempi più tardivi, rappresenta il santo con accanto uno zoccolo, ritenuto strumento del suo martirio.

Dalla corrispondenza epistolare giunta fino a noi fra San Vigilio e

Sant'Ambrogio vescovo di Milano![]() ,

sappiamo che fu quest'ultimo a inviare in Trentino Sisinio, Martirio e Alessandro per coadiuvare il vescovo Vigilio nella sua attività

pastorale.

,

sappiamo che fu quest'ultimo a inviare in Trentino Sisinio, Martirio e Alessandro per coadiuvare il vescovo Vigilio nella sua attività

pastorale.

Bernardo di Clès

Bernardo

Clesio

Umanista italiano (Clès 1485 - Bressanone 1539). Vescovo-principe di Trento (1514), cardinale nel 1530, fu consigliere di Carlo V e avversò la Riforma protestante. Mecenate, fu in rapporti di amicizia con Erasmo da Rotterdam e con Pietro Bembo.

Ferdinando I d'Asburgo

Imperatore (Alcalá de Henares 1503 - Vienna 1564). Fratello minore dell'imperatore Carlo V, che nel 1521 gli cedette le terre ereditarie asburgiche (in cambio della rinuncia allo smembramento dei Paesi Bassi) e, nel 1531, il titolo di re dei Romani. Dopo una lunga collaborazione col fratello, in seguito all'abdicazione di Carlo ebbe nel 1558 il titolo imperiale. Educato in Spagna dal nonno Ferdinando II il Cattolico, sposò (1521) Anna Iagellona e pose la sua candidatura al trono di Ungheria e di Boemia che ebbe, almeno formalmente, alla morte del cognato, re Luigi II (1526). Pur lottando contro la diffusione della Riforma, si adoperò sin dal 1531 per una soluzione pacifica, elaborando, anche per conto di Carlo V, la Pace di Augusta (1555). Pazienza e tempismo politico gli permisero di consolidare il potere nell'Est: concesse alcune libertà all'Ungheria stremata dopo la sconfitta subita dai Turchi a Mohács (1526). Con i Turchi stipulò nel 1547 un patto; in Boemia sottomise gli avversari dopo la guerra di Smalcalda (1547), ma usò una prudente tolleranza religiosa. Con gli ordinamenti del 1527 varò una decisiva riforma amministrativa, che diede l'avvio alla trasformazione dell'Austria in Stato moderno, centralizzato ed efficiente.

Massimiliano II d'Asburgo

Imperatore (Vienna 1527 - Ratisbona 1576). Primogenito di Ferdinando I, gli succedette nel 1564 (dopo essere già stato eletto re di Boemia e di Germania, 1562, e re d'Ungheria, 1563), garantendo formalmente la continuità del cattolicesimo in Germania, nonostante le sue inclinazioni luterane. Per mantenere l'unità della casata sposò (1548) la cugina Maria, figlia di Carlo V, e concedette la figlia Anna in moglie a Filippo II (1570). In Austria e Ungheria tollerò le conversioni al luteranesimo di molti nobili, pur rafforzando la Chiesa cattolica; verso i Turchi adottò una politica di pace. Eletto re di Polonia nel 1575 in concorrenza con Stefano Bathory, morì improvvisamente l'anno successivo dopo aver assicurato la successione al figlio Rodolfo.

|

Matthioli www.alessandrina.librari.beniculturali.it

Icones veterum aliquot ac recentium Medicorum

Philosophorumque Matthioli’s Commentary on Dioscorides

is one of the great books of the Renaissance. It had a major influence

on medicine and botany around Europe, being bought and, one presumes,

consulted by scholars from Cambridge to Cracow[1]. In its importance in its subject, it

can be compared with Vesalius’ Fabrica in anatomy, or with

Fracastoro’s ideas on contagious diseases[2]. As an object of beauty it graces the

display cabinets of many libraries, and it may still be studied with

profit for the botanical and historical information it contains. Yet

how and why Matthioli and his book came to occupy this position of

preeminence are questions that have not been adequately examined, for

there is always a tendency to assume that the reasons for the success

of any literary work are almost self-evident: it was a great success,

therefore it must have been a brilliant book. But, as we know,

brilliant books may meet with commercial and academic failure; and

best-sellers may not be the most deserving of that honour. Why was it

that Matthioli’s book and not that of, say, Fuchs It should be stated at the outset that

any answer must take account of chronology: it is not only that the

book itself changed as it went through various editions and

translations, generally becoming larger with additional material, but

Matthioli’s own career and circumstances changed. The doctor at

Trento and Gorizia in the 1530’s and 1540’s was not the

international figure that he became in the 1550’s; the provincial

physician was not the later imperial physician of Archduke Ferdinand,

sitting in Prague at the centre of a spider’s web of correspondence.

In 1540, when he was preparing the first edition of the Discorsi,

Matthioli was far from being the authoritative, even manipulative

figure, of the 1560’s, whose influence was such that his disapproval,

or even his failure to mention one’s discovery or identification of

a new plant, was tantamount to a professional death sentence. The

pan-European network of correspondents developed by Matthioli, with

the aid of the ubiquitous imperial postal service, was very different

from the very local contacts he displayed in the first edition of the Discorsi.

Indeed, it was his book’s success that gave him this position of

eminence, not the reverse. Nicolò de Bascarini da Pavone, the

publisher of the 1544 edition, was not the most celebrated printer in

Venice, for he was only just beginning his career as a printer and

this was his first major success[3]. It was only with the second edition of

the Discorsi in 1548, published by Vincenzo Valgrisi, that

Matthioli found a publisher with a truly international reputation. A

glance at the printing privileges obtained for the 1544 and the first

Latin edition of 1554 shows a major difference of ambition. In 1544

protection against plagiarism was obtained only from Venice and the

Pope: in 1554 this had been extended beyond the Alps with the approval

of the King of France, and the greatest patron of them all, the Holy

Roman Emperor himself. Nor can we set the success of the Discorsi

down to the quality of the book’s illustrations, for these did not

make their appearance until the first Latin edition of 1554, twelve

years after Leonhart Fuchs’ beautifully illustrated De historia

stirpium and more than twenty years after Brunfels’ Herbarum

vivae eicones had shown how the printing press could transform the

study of plants. Indeed, the first illustrated Renaissance edition of

Dioscorides was not that of Matthioli, but the 1543 Frankfurt edition,

supervised by the noted plagiarist Wilhelm Ryff. But Matthioli was far

from alone in the relative slowness of his response to the new

iconography, or in having his doubts about the value of a drawing of a

plant at only one stage in its life. One should not forget that the

provision of illustrations on the lavish scale of later editions not

only slowed up a book’s production but also added considerably to

its cost at first[4]. How then are we to explain the perhaps

unexpected success of this work by a provincial physician, trained by

no expert herbalist and known, if at all, to the outside world only by

a relatively undistinguished treatise on the morbus gallicus

and a description of his patron’s Palace at Trento?[5] I want to look closely at Matthioli’s

art of commentary, focussing in particular on the 1544 Discorsi

and comparing certain passages in them with the treatment accorded to

the same passage by Matthioli’s rivals and later in the first Latin

edition of 1554 and as it appeared at the end of his life in the Latin

edition of 1583[6]. In

so doing, I shall be demonstrating features that have, until now, been

little studied, yet which may help to explain why other doctors and

scholars came to value his work so highly. One point should be made clear at the

outset. Although there were in Italian universities by the late

sixteenth century lectures on Dioscorides, and although the practice

of taking Dioscorides along on a herborizing expedition to identify

plants was widespread, at the time that Matthioli began his work, most

of the renaissance commentaries on Dioscorides were philological

enterprises, not the direct result of university lectures, like those

on some Galenic and Hippocratic texts[7]. Hence the variety of words used to

describe these productions, annotationes, annotamenta, censurae,

scholia, as well as commentarii. They are works from the

study, not the lecture room, and they display the contemporary

apparatus of scholarship, quotations, references, and textual

discussions, to a much greater extent than would in general have been

the case for a medical commentary. Although Matthioli’s work takes the

form of a commentary, with the text printed in bold Roman type with

the commentary beneath in a smaller italic font, it lacks some of the

common features of such writings. There is no painstaking explanation

of individual words in Dioscorides’ Greek, no line by line

explication of the ancient text, such as we find, for instance, in the

commentary on the medical poem of Aemilius Macer 1 - Chiamasi il soncho uolgarmente in Thoscana Cicerbita e

Crespine anchora; 2 - Notissime a tutta Italia sono le Endiuie et le Cicoree.... 3 - Non è dubbio che la Condrilla...

sia altro che spetie di vera Cicorea. The name of the plant is given in Italian,

but in such a way as to avoid an impression of philological

didacticism, and with a pleasing stylistic variatio. Matthioli’s Latin edition of 1544 is

very largely a straightforwardly accurate translation from the Italian.

But there are changes in wording, some of them subtle: sonchus in

Hetruria, ubi Latinum nomen perdurat, Cicerbita vulgo vocatur. A minor error (the name Crespine) is

quietly corrected, and the doubts of Marcellus Virgilius Later editions, in Italian or in Latin,

keep much of the wording of 1544 or 1554, and they influence one

another. A few entries receive a near total reshaping, but far more

often the new material is inserted into the old text, a clause here, a

sentence there, sometimes a paragraph, and even on rare occasions

several pages, before Matthioli returns to his initial wording. But

the whole procedure is performed with such skill that the casual

reader can hardly detect the joins. But it is above all the fact that

Matthioli published this work in Italian that is most striking.

Although translations of classical works on ancient medicine were

gradually becoming available in Italian - Fausto da Longiano’s

version of Dioscorides was published in 1542, that of Montigiano in

1546, Tarchagnota’s translations of Galen in the late 1540’s -,

they were rarely accompanied by scholarship of this detail or this

length. Matthioli breaks new ground in publishing his work for an

Italian audience, one that was not entirely at home with Latin, but

would retain an interest in botany and pharmacology. Its intended

audience, one might suppose, is also less wealthy than the average

university medical student, although far from poor. A work like this

may have gained at least local success because of its choice of

Italian, which allowed it to establish itself within N. Italy, but

this does not explain its success entirely. There are other qualities

which, to my mind, helped it to become the European bestseller that

Valgrisi at least had hoped for it once it had been turned into Latin. But what of the content? The 1544 edition

is not a particularly grand achievement as far as the technical side

of its production goes. The type is not always clear, the paper is of

middling quality, the aids to the reader are confined to a single

index of plant names and an even briefer index of Tuscan words. The

1554 Latin edition expands the indexes to give a fuller list of

contents, but, curiously, it does not implement one change already in

the 1550 Italian edition that was to become part of the later Latin

editions. In those the indexes have been transformed into a guide to

medicine: alongside the list of contents, of weights and measures, and

of plates, there are detailed indexes giving references to the

properties of the drugs and their usages. One gives the parts of the

body for which they are appropriate, another the type of disease,

including ulcers, poisoning, and fractures; another the drugs that can

be used as emetics; another those useful as beauty aids. Together

these lists allow the book to be easily consulted, if one starts from

a medical problem, and not from one of botanical or zoological

identification. But what of Matthioli’s own scholarship

as revealed in 1544, for it was this that gave him credibility among

his peers? We may divide this into two, his own botanical expertise

and academic learning. The former is easily evident throughout. On the Potamogeto, he says: “Hollo piu volte veduto io

spetialmente in alcuni laghi della valle Anania (the modern Val di

Non) e ritoltolo con le proprie mani.” Rhubarb

he compares with other odourless plants he has seen growing in Germany

and Styria. He reports the large sea eagles, the agrotti, he has seen

in the lagoons at Orbetello ‘nelle nostre Maremme di Siena’, a

passing hit at Marcellus, who had emphasised that Dioscorides’

description of the ‘ossifrago uccello’

was second-hand and could be entirely legendary. Matthioli

tells jokes about Etruscan peasants who have foolishly attempted to

remove the skin from asses who have fallen into a stupor from eating

hemlock, and who have been frightened when the animal suddenly woke up

and bellowed. Practical

details are offered along with personal reminiscence: “Veggansi il

mese di Marzo fiorite tutte le spezie preddette dell’ elleboro nero

l’una appresso all’altra della grandissima selva, che si passa di

andare da Gorizizia à Lubiana, città di Carniola, ove l’ho spesso

tolto per i bisogni.” His account of mandragora takes us into

the world of ‘Ciurmadori et Cerretani’, who produce fake roots for

sale in Rome for 25 or 30 ducats a time, and whose secrets were

revealed to him by a travelling herbalist he had treated for syphilis.

His description of aconito is full of vigorous description and

reminiscences of it growing in the mountains near Trento, and sold on

Ponte Sant’Angelo in Rome. Most striking of all is his story of the

experiments carried out by his master Gregorio Caravita before the

Pope in November 1524 on two Corsican assassins. Caravita had invented

an antidote, which he gave to one man, who had eaten large quantities

of the poisonous plant in a marzapane: he recovered in three days. The

other, who had taken far less of the poison but none of the antidote,

died in agony after 17 hours, exactly as Avicenna had described. These memories serve three purposes. They

establish Matthioli’s credentials as a practical observer; they

provide witnesses or the means of authenticating his statements; and

they break up an otherwise bald exposition. But, it should be noted,

in this Matthioli was doing nothing unusual: personal reminiscences

can be found in the work of Brasavola at Ferrara, Valerius Cordus at

Wittenberg, or the English botanist William Turner But it is the second type of scholarship,

Matthioli’s own academic learning, that may give us the clue to the

success of the 1544 Discorsi. It is not that Matthioli shows

himself to be a particularly learned or a particularly ignorant

botanist[10]: what is striking is the balance that he

manages to keep between necessary exposition and superfluous

information. We know a good deal about his sources: Fuchs, Brasavola,

Leoniceno, Manardi, Barbaro Similarly,

birds and plants that

he believes are not longer to be found or where Dioscorides’

description is too vague for precise identification are dismissed

curtly, without a long list of possible modern

names. Matthioli does not make a fetish out of nomenclature. At times,

it is enough for him to make identification clear simply by his

translation and by including the name in his first sentence. There are

not the long lists of names that can be found in other commentaries,

and which, in the later editions of his own commentary, form a regular

coda to each entry, giving the name in a variety of languages,

including Bohemian and Polish as well as Italian, Spanish and German.

But a comparison with other commentators shows how little of

significance Matthioli has missed. He also has a gift for summarising

complex issues clearly. His discussion of rhubarb sets out clearly the

terms of the debate; he notes the difficulty of identification of the

species described by Dioscorides, and that Manardi changed his mind when

he thought he had acquired from Muscovy the genuine article (far

superior to that grown widely in Italian gardens). Matthioli comments

on the ease with which rhubarb can be bought at Venice - and its high

price, its own weight in gold, almost certainly the result of speziali

exaggerating its healing powers. He also wonders about this alleged

potency, since in Italy it is often given to small children and

pregnant women with no obvious major side-effects. Here I suggest is a very good reason for

the success of the 1544 commentary: its gift for precise and balanced

exposition. Like the rules of Gaelic vowel harmony, it is always

‘slender with slender, broad with broad’. Where Matthioli has

something important to say, he says it; when he has not, he does not

burden us with the irrelevancies of others. Matthioli is, in short, a

commentator of genius. Subsequent editions bring their own

advantages and disadvantages. The 1554 Latin edition shows a

transition to a slightly different book, a more academic and scholarly

production. Quotations from Galen or Hippocrates are expanded, and

there is more attention paid to textual questions. For example,

Matthioli notes, following Marcellus, that the younger manuscripts of

Dioscorides do not have the word ‘kenos’, ‘hollow’, in their

account of the sonchos: some Latin translators have the word

‘inanis’, and it is found also in Pliny’s description of the

plant, which depends closely on its Greek model. But since the word is

found in Oribasius and in the oldest codices, it is unlikely to be a

medieval addition taken over from a comment in Pliny. There is

expansion and also correction of his own errors: the androsace now

grows in Syria, not near Soria in Italy, and, thanks to Luca Ghini,

Matthioli can offer for the first time an identification with an

Italian plant, one growing on the shores of Etruria. The discussion on

the kyphi becomes more erudite, as does that on the mysterious

Ossifragus. Here the quotations from Aristotle and Pliny are given in

full, and Albertus Magnus The transformation is complete by

Matthioli’s death. Although the form and much of the wording is

still that of the commentary, the organisation, layout and feel of the

huge double volume of 1583 have all altered. Although the discussions

about manuscripts are both fuller and more sophisticated, not least

because of Matthioli’s access to two early Viennese manuscripts of

the Greek Dioscorides, one the celebrated sixth century Codex of Julia

Anicia, the emphasis is less on Dioscorides than on the materia medica

and its uses. As I have already remarked, the book’s indexes make

medical consultation considerably easier. Gaps are filled wherever

possible: oryza at last receives a full botanical treatment, and,

thanks to Ghini, the stratiotes can be finally identified. The plates

are both larger, more numerous, and better drawn. The list of his

collaborators grows ever longer, from Francesco and Andrea Calzolari

to Girolamo Donzellini and Ulisse Aldrovandi. The mysterious plant

androsace, for which Ghini had suggested one identification, has now

two, provided by Cortusio from his knowledge of Syrian plants. Two

substantial plates dominate the relatively small amount of text in

which Cortusio’s discovery is recorded. As the book

grew in size, so too did Matthioli’s ego. The tendency, already

visible in the second edition, to point up the failings

of others in marginal headings and to magnify his own achievement is

now unmistakable. He is only too well aware of the eminence and

importance of this book as a compendium of the botanical and medical

lore of the sixteenth century, and of his part in it. His own error

over the ‘ossifragus’ (now beautifully illustrated) is blamed on

the wickedness of scribes. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in

the entry for aconitum, which is expanded to twice the length of the

original entry in 1544. This is in part the reflection of a massive

debate over the correct identification of Dioscorides’ plant that

involved most of the leading botanists of Europe, as well as the

wholesale slaughter of small animals and of chicken as the poisonous

powers of one herb after another were tested. Matthioli’s original

views remain unchanged, despite the assault on them by Fuchs and

Gessner. He responds in three ways. First, thanks to Cortusio and

Donzellini, he includes detailed pictures of the plant at different

stages of its life. Secondly he retells his own experiences, including

a gruesome account of his own experiment with an antidote. He tried it

out in 1561 on two criminals at Prague, one of whom lived, but only

just, the other of whom suffered long agonies before finally

succumbing. Matthioli was, of course, repeating the experiment of his

old master, Caravita, but his description is more detailed and more

cold-blooded in its details. It is preceded by an appeal, several

lines long, to witnesses to Matthioli’s veracity: imperial courtiers,

royal physicians like Alessandrino and Crato von Craftheim, ambassors

and the like are summoned to confirm what Matthioli had shown and

taught them. The language and style of this new passage indicates that

its focus is not Dioscorides but Matthioli, and its purpose is not to

explicate Dioscorides but to defend Matthioli. How could anyone

believe that he, the great Matthioli, the imperial physician, was

telling tales? ‘Come touch and see that Matthioli is not describing

legends’. This

huge entry, seventeen pages long, exemplifies what Matthioli and his

book came to stand for: an authoritative, comprehensive, experiential,

learned, and beautifully illustrated account of all that was known

about materia medica. But, as I have suggested, we should not read all

this back into the first edition of the Discorsi of 1544, or

automatically assume that this explains the success of the earlier

volume. As I have argued today, we must look at that book on its own

merits against the background of other discussions of Dioscorides. By

doing that, we may come to a proper appreciation of Matthioli’s art

of the commentary. |

Sommario cronologico della vita e delle opere

a cura di Renzo Console

http://chifar.unipv.it/museo/Console/mattioli05/MttCrn.htm

Abbiamo adottato la grafia “Mattioli” perché è quella quasi sempre usata oggigiorno; ma dobbiamo notare che era identificato come “Matthioli” in tutte le sue opere stampate quando era in vita, ed è molto probabile che questa grafia fosse quella che egli stesso usava correntemente.

Quando viveva Mattioli, in tutti i territori sotto il dominio di Firenze si usava un calendario diverso da quello tradizionale. Infatti l’anno per i fiorentini (e i senesi come Mattioli) iniziava il 25 marzo, data del concepimento di Cristo e festa dell’Annunciazione di Maria. Così le date espresse secondo lo stile fiorentino (adottato anche da Mattioli) erano un anno indietro tra il 1º gennaio e il 24 marzo. Questo conteggio dell’anno si chiamava “ab incarnatione” per distinguerlo da quello usuale.

Mattioli nacque e morì nei primi mesi dell’anno (tradizionale), per cui abbiamo due date diverse sia per la sua nascita che per sua la morte secondo lo stile adottato per esprimerle. Infatti per il calendario gregoriano il 1501 va dal gennaio 1501 al dicembre 1501; per il calendario in uso nei domini fiorentini i primi tre mesi dell'anno - gennaio, febbraio e marzo fino al 24 - sono ancora 1500.

Gli studiosi devono inoltre fare attenzione allo stile delle date per quanto riguarda tutta la biografia di Mattioli, con la complicazione aggiuntiva dovuta al fatto che il papa Gregorio XIII riformò il calendario nel 1582 saltando 10 giorni in ottobre. Firenze si allineò a tutto questo solo a partire dal 1750.

Matthiola

carnica - Violaciocca selvatica

foto di Luciano Gaudenzio

Il genere Matthiola, composta da piante erbacee della famiglia Crocifere o Brassicacee, comprende circa 50 specie spontanee delle regioni mediterranee, dell'Egitto e del Sudafrica, utilizzate nei bordi misti, in gruppi isolati, nelle aiuole, nelle roccaglie dei giardini rocciosi e anche nelle decorazioni dei balconi.

La diffusione di queste piante, che raggiunse l'apogeo nei secoli XVII e XVIII, è stata favorita dalla loro notevole rusticità. Esse possono essere annuali, biennali e perenni. Hanno fiori regolari, a 4 petali, per lo più rosa o lilla. Il genere comprende le seguenti specie che sono le più importanti:

Matthiola bicornis

Matthiola fruticulosa - violaciocca minore

Matthiola incana - violaciocca d'inverno

Matthiola longipetala

Matthiola lunata

Matthiola maderensis

Matthiola maroccana

Matthiola odoratissima

Matthiola ovatifolia

Matthiola parviflora

Matthiola perennis

Matthiola sinuata -violaciocca sinuata

Matthiola tricuspidata - violaciocca selvatica

Matthiola fruticulosa ssp. valesiaca - violaciocca alpina

Matthiola

fruticulosa ssp.

valesiaca - Violaciocca alpina

carrellata di Elio Corti - 1972

Matthiola incana - Violaciocca d'inverno

Dictionnaire

historique

de la médecine ancienne et moderne

par Nicolas François Joseph Eloy

Mons – 1778

Dictionnaire

encyclopédique

des sciences médicales

1864-1888

[1]

The Wellcome

Library copy of the 1544 edition cost an early owner, Pietro de Col

Agordino, 14 Venetian Lire. (Chjeck

Caius)

[2]

Note his praise of these men (inter alios) in the Prologo to the 1544 Discorsi:

il facondissimo Fraccastoro, il valentissimo Vesalio![]() primo anatomista del

mondo.

primo anatomista del

mondo.

[3] His career was short, from 1542 to 1553; see Short Title Catalogue of Books printed in Italy and of Italian Books printed in other Countries from 1465 to 1600, London, British Museum, 1958, p. 770; Short Title Catalog of Books printed in Italy and of Books in Italian printed Abroad, 1501-1600, vol. 3, Boston, G. K. Hall and Co, 1970, p. 440.

[4] It should also be remembered that the illustrations in the 1554 edition were drastically changed in later editions.

[5]

De morbis gallici curandi ratione dialogus,

Bologna, 1530; Magno palazzo del cardinale di Trento, Venice, 1539.

[6] I am aware that each edition was different from its predecessors to a greater or lesser extent, but a view of the book at three distinct and important stages emphasises the very different qualities the work took on as it progressed.

[7] Frigimelica’s commentary, Oxford, Bodleian Library, Canonici lat. misc. 31, was delivered as lectures at Padua in 1530; that of Valerius Cordus was given first at Wittenberg in 1539/40.

[8] I have consulted this in the Medici Antiqui Omnes, Venice, sons of Aldus, 1547.

[9] P. Godman, From Poliziano to Machiavelli. Florentine Humanism in the High Renaissance, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1998, pp. 209-234.

[10] He is inferior in learning to Poliziano and to Leoniceno, for example, and in botanical knowledge to Luca Ghini; but he is also superior to the former in botany and to the latter in academic scholarship.