Lessico

Numida meleagris

Faraona - Gallina di Faraone

Gallina di Numidia

Caratteristiche cefaliche di alcuni appartenenti al genere Numida

Uccello dell’ordine dei Galliformi, famiglia

Fasianidi, sottofamiglia Numidini che trae il nome della specie - meleagris – da Meleagro![]() , eroe della mitologia greca, figlio di Eneo re di

Calidone in Etolia e di Altea

, eroe della mitologia greca, figlio di Eneo re di

Calidone in Etolia e di Altea![]() .

.

La sottofamiglia dei Numidini è composta, secondo Bernhard Grzimek, da cinque generi:

Phasidus: Phasidus niger – Faraona nera

Agelastes: Agelastes meleagrides – Agelaste

Guttera: Guttera plumifera

e

Guttera pucherani (Numida crestata)

Acryllium: Acryllium vulturinum – Numida vulturina

Numida: Numida meleagris – Gallina di Numidia![]() o

Gallina di Faraone

o

Gallina di Faraone

La Numida meleagris è stata suddivisa in diverse sottospecie che presentano l’elmo corneo di foggia assai diversa da una sottospecie all’altra. Grzimek elenca le seguenti: meleagris, sabyi, galeata, mitrata, major.

La nostra attuale faraona domestica sarebbe la forma d’allevamento della Numida meleagris galeata originaria dell’Africa occidentale, introdotta in America e in Europa dai Portoghesi all’epoca delle grandi scoperte geografiche.

Nell’antichità venne dapprima addomesticata solo la sottospecie marocchina – Numida meleagris sabyi, più tardi i Romani importarono in Europa anche la sottospecie dell’Africa nordorientale – Numida meleagris meleagris.

Descrizione

della sottospecie da allevamento

Numida meleagris galeata

La sottospecie da allevamento della gallina di Faraone raggiunge una mole discreta - sino a 2 kg - ed è caratterizzata da testa e collo parzialmente nudi e ricoperti di pelle biancastra con alcune appendici cutanee. A livello della base del becco, che appare ricurvo, si osservano due bargigli rossi, più grandi e spesso attorcigliati nel maschio. Sul capo, al posto della cresta, si trova un astuccio corneo a forma di piccolo elmo sorretto da un processo osseo. Il corpo ha un profilo particolare ed è coperto da penne che presentano piccole e regolari macchie bianche di forma rotonda. Le zampe portano quattro dita; manca lo sperone.

La faraona è buona produttrice di carne che ha caratteristiche organolettiche peculiari. Limitata è invece la produzione di uova, del peso di 40-45 g. La femmina non è una buona covatrice. Lo sviluppo embrionale dura 27 giorni. I pulcini sono per breve tempo ricoperti di peluria, presto sostituita dalle penne giovanili. Non esiste un pronunciato dimorfismo sessuale; il maschio è più alto. La femmina appare, invece, tozza ma più pesante. Di quando in quando le faraone strepitano incessantemente: il grido più noto è un forte ciké-ciké-ciké.

|

Guinea

Fowl All authors agree that the domestic guinea fowl

was derived from the helmeted guinea fowl - Numida meleagris - of Africa. There were at least several

independent domestications involving more than one subspecies.

Present-day commercials stocks were probably all derived from the West

African subspecies Numida

meleagris galeata. Wild

Species Classification.

Belshaw (1985) has classified guinea fowl as order Galliformes,

family Numididae, but Howard and Moore (1984) placed them in

family Phasianidae and subfamily Numidinae. There are

four genera (Agelastes, Guttera, Numida, Acryllium) comprising seven species.

Genus Numida consists of a

single polytypic species meleagris

and 22 subspecies. Crowe (1985) has used a simpler classification

of Numida meleagris involving

nine well-marked subspecies which fall into three groupings: West

African - N.

m. galeata and

sabyi Description.

Crowe (1985) described helmeted guinea fowl as opportunistic omnivores

which inhabit open savannah and mixed savannah-bush. They are

gregarious in the nonbreeding season, and monogamous as breeders.

Females, especially in the breeding season, emit a characteristic

two-note ‘buck-wheat’ call; males respond with a single note; both

sexes have a rattling alarm call. Males are slightly larger than

females but otherwise they exhibit almost no sexual dimorphism. Adult

body size ranges from 0.7-2.0 kg (Long, 1981). The crown of the head

carries a bony helmet with a horny sheath, and a pair of wattles hang

from the gape. The nares are exposed, but in subspecies inhabiting hot

dry areas the nares are surrounded with warts or cartilaginous

bristles. Blood supply to the helmet, wattles, and cere may have

importance in thermoregulation. The legs are long and powerful,

lacking a spur. Plumage is monotypic. The ground color is black, with

white spots intermeshed with white vermiculation; the spots on the

outer margins of the secondaries are enlarged to form bars. Incubation

time is 27-28 days, and clutch size varies from 6-10 eggs. According

to Crowe (1985), the West

African galeata subspecies is small to medium-sized, and has a naked cere

and rounded red wattles. N. m.

sabyi is isolated in Morocco and differs very little from N. m. galeata. The East African meleagris and somaliensis subspecies

are medium-sized, they have long bristles on the cere, and rounded

blue wattles. The Central-South African group are relatively large

birds. They have a naked cere (except for N.

m. papillosa which has warts around the rim) and triangular-shaped

blue wattles with red tips. Distribution.

Helmeted guinea fowl occur naturally throughout most of sub-Saharan

Africa. There is an isolated northern population - N.

m. sabyi -

in Morocco (Crowe, 1985). Many

introductions have been made, some involving wild birds and some

involving domestic stocks, and reintroductions have been made to areas

of Africa where they had been exterminated (Long, 1981). The

population in Yemen was probably introduced long ago; it is similar to

the East African subspecies, for which some authors use the

designation ptilorhyncha. The

population in Malagasy was probably also introduced; it is classified

as N. m. mitrata. Many

oceanic islands have been stocked, not all of them successfully.

Repeated introductions in New Zealand, Australia, and the United

States met with general failure. There were introductions to most

islands of the Caribbean, sometimes with wild birds and sometimes with

domestic stocks which became feral. Some of these introductions were

made in the 16th century and others arrived as live provisions on

African slave ships. Populations flourished but many later became

extinct because of hunting pressure and predation by the introduced

mongoose. Viable wild or feral populations persist in Haiti, Dominican

Republic, and Cuba. Domestication

And Early History It

is likely that many separate domestications have occurred in many

separate places over time. According to Crowe (1985), wild populations

of Numida meleagris readily

become commensals of man, increasing in numbers and distribution

because of the water, roosting, and feed resources resulting from

human activity. However, unlike the situation for other poultry

species, there is little indication in the historical record that

guinea fowl were utilized other than as a human food resource. Belshaw

(1985) makes only brief mention of their use in religion and folklore

and of feathers in decoration. Eggs were probably of first importance

and edible meat was secondary. Information

on history of domestication within Africa is scanty and, except for

Egypt, depends on oral history. Belshaw (1985) stated that early

domestication had occurred in two areas - in southern Sudan and in West Africa - but

the dates are not certain. The process of domestication probably

continues even now. Guinea fowl were depicted in a mural from the

Egyptian fifth dynasty about 2400 B.C. but there is no evidence that

the birds were domesticated then. They also appear in archaeological

remains at Farnak dated from about 1900 B.C. and at Thebes (1570-1300

B.C.). It is supposed that they were artificially hatched and reared

in large numbers concurrently with chickens during that period (Belshaw,

1985) but evidence is lacking; chickens are known to have been in

Egypt at that time, but they were absent from the archaeological

record in subsequent centuries, not appearing again until about 600

B.C. under Greek and Persian influence. Guinea

fowl were well-known to the Greeks and Romans in classical times. They

were mentioned by Ovid, Aristotle, Pliny, Varro, and Columella.

According to Zeuner (1963), the Greeks called the bird melanargis

(black-silver) which was corrupted to meleagris

and became associated with Greek mythology. Moubray (1854) related

that story: “... the

Meleagrides, the sisters of Meleager ...

who

was cruelly put to death, bewailing the death of their unfortunate

brother, were metamorphosed into Guinea-fowls, the shower of tears

they shed bedecking their otherwise sable plumage with white spots ...“.

Wood-Gush

(1985) indicated that the Moroccan subspecies N. m. sabyi was kept as a sacred bird on an Aegean island in the

fourth century B.C. The Romans later knew this bird as the Numidian

fowl. They also had birds of the East African subspecies which they

called Meleagris and which they preferred. Both terms were

eventually utilized by Linnaeus in formal naming of the genus and

species. Guinea fowl were highly regarded as a food item by the Romans

who must have distributed them throughout the Roman Empire. Zeuner

(1963) mentioned bones of guinea fowl discovered in a Roman camp in

the Taunus Mountains of West Germany, and Belshaw (1985) refers to a

leg bone carrying a metal ring found in ruins of the Roman town of

Silchester in England. With

decline of the Roman Empire, guinea fowl seem to have disappeared from

Europe leaving almost no trace in the historical record. Mongin and

Plouzeau (1984) refer to possible exceptions. They may have persisted

in Greece and Italy, since Wood-Gush (1985) has noted a reference to

the keeping of guinea fowl in Athens during the tenth century. The

Portugese of the late 16th century are generally credited with

rediscovering guinea fowl on the west coast of Africa, from where the

bird acquired its common name. The term poule

de Guinée may have been used first in 1555 by Belon (Mongin and

Plouzeau, 1984). The Portuguese took these guinea fowl to Europe, to

the Americas, and elsewhere. Diffusion through Europe was probably

concurrent or perhaps slightly in advance of turkey introductions,

resulting in unfortunate confusion of names and identity of the two

species which persists in their scientific nomenclature. Nearly

all modern guinea fowl are likely to have been derived from Portuguese

introduction of the West African subspecies Numida meleagris galeata. There are indications that new

commercial hybrids may involve blends of several subspecies (Belshaw,

1985) but documentation in the technical literature is lacking.

Domestic birds in Malagasy and those introduced from there to other

localities may be domesticated Numida

meleagris mitrata. Those of eastern Africa are likely to be

domesticates of meleagris and somaliensis subspecies,

and those of the Mediterranean area may still bear traces of both East

and West African subspecies. |

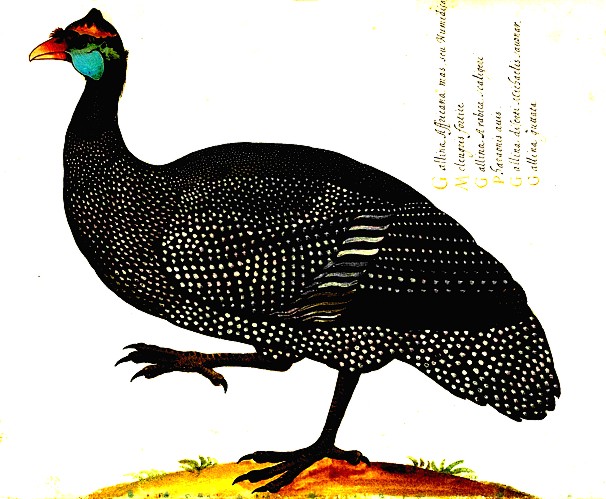

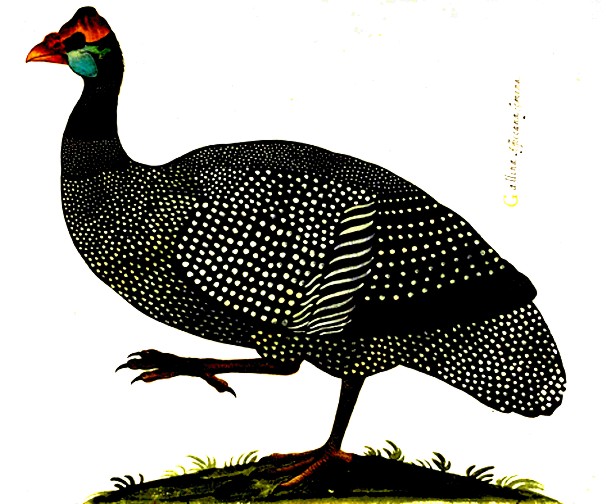

Gallina Affricana femina

acquarelli![]() di Ulisse Aldrovandi

di Ulisse Aldrovandi

Gallina Affricana mas