Lessico

Ermia

Sozomeno

Hermias Sozomenos

Hermias Sozomenus Salamanes

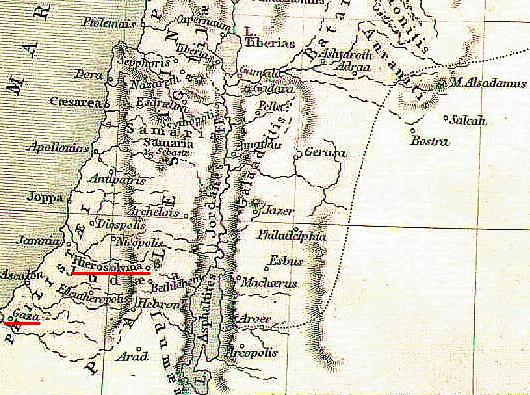

In greco HermeŪas SÝzůmenos. Storico, nato a Betelia presso Gaza agli inizi del V secolo, vissuto a Costantinopoli allíepoca di Teodosio II (401-450). Oltre a uníopera storica perduta che trattava dei primi tre secoli cristiani fino al 323 (dall'ascensione di Gesý fino alla sconfitta dell'imperatore romano Licinio nel 323/324), scrisse una Storia Ecclesiastica in 9 libri che comprende, nel testo pervenuto, il periodo dal 323 al 425 e che Ť basata su uníampia documentazione. Le fonti sono elaborate nel quadro di una narrazione ricca di aneddoti e di avvenuti miracoli, e la sua visione della storia Ť tendenzialmente apologetica.

Isola

Gallinara![]() di Ermia Sozomeno

di Ermia Sozomeno

Ecclesiastical History III,14

Although the Thracians, the Illyrians, and the other European nations were still inexperienced in monastic communities, yet they were not altogether lacking in men devoted to philosophy. Of these, Martin, the descendant of a noble family of Saboria in Pannonia, was the most illustrious. He was originally a noted warrior, and the commander of armies; but, accounting the service of God to be a more honorable profession, he embraced a life of philosophy, and lived, in the first place, in Illyria. Here he zealously defended the orthodox doctrines against the attacks of the Arian bishops, and after being plotted against and frequently beaten by the people, he was driven from the country.

He then went to Milan, and dwelt alone. He was soon, however, obliged to quit his place of retreat on account of the machinations of Auxentius, bishop of that region, who did not hold soundly to the Nicene faith; and he went to an island called Gallenaria, where he remained for some time, satisfying himself with roots of plants. Gallenaria is a small and uninhabited island lying in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Martin was afterwards appointed bishop of the church of Tarracinae (Tours). He was so richly endowed with miraculous gifts that he restored a dead man to life, and performed other signs as wonderful as those wrought by the apostles. We have heard that Hilary, a man divine in his life and conversation, lived about the same time, and in the same country; like Martin, he was obliged to flee from his place of abode, on account of his zeal in defense of the faith.

(Ecclesiastical

History - from a.d.

323 to a.d. 425 - translated

from the Greek. Revised by

Chester D. Hartranft, Hartford Theological Seminary - www.ccel.org) - Questo

Martino Ť il futuro San Martino di Tours![]() (316 o

317 - 397).

(316 o

317 - 397).

Hermias Sozomen practiced the law at Constantinople, at the same time with Socrates Scholasticus (Constantinople ca. 380-ca. 450). His ancestors were not mean; they were originally natives of Palestine, being inhabitants of a village near Gaza, called Bethelia. This village was very populous in times past, and had most stately and ancient churches. But the most glorious structure of them all was the Pantheon, situated on an artificial hill, which was the tower as it were of Bethelia, as Sozomen relates in chap. xv. of his fifth book.

The grandfather of Hermias Sozomen was born in that village, and first converted to the Christian faith by Hilarion the monk. For when Alaphion, an inhabitant of the same village, was possessed with a devil, and the Jews and physicians, attempting to cure him, could do him no good by their enchantments, Hilarion, by a bare invocation of the name of God, cast out the devil. Sozomenís grandfather, and Alaphion himself, amazed at this miracle, with their whole families embraced the Christian religion.

The grandfather of Sozomen was eminent for his expositions of the Sacred Scriptures, being a person endowed with a polite wit, and an acuteness of understanding; and besides, he was well skilled in literature. Therefore he was highly esteemed by the Christians inhabiting Gaza, Ascalon, and the places adjacent, as being useful and necessary for the propagating of religion, and could easily unloose the knots of the Sacred Scriptures. But Alaphionís descendants excelled others in their sanctity of life, in kindness to the indigent, and in other virtues; and they were the first that built churches and monasteries there, as Sozomen says in the passage above cited, where he also adds, that some holy persons of Alaphionís family were surviving even in his own days, with whom he himself conversed when very young, and concerning whom he promises to speak more afterwards.

Most probably he means Salamanes, Phusco, Malchio, and Crispio, brothers, concerning whom he speaks in chap. xxxii. of his sixth book. For he there says that these brethren, instructed in the monastic discipline by Hilarion, were, during the empire of Valens, eminent in the monasteries of Palestine; that they lived near Bethelia, a village in the country of the Gazites, and were descendants of a noble family in those parts. He mentions the same persons in the fifteenth chapter of book viii., where he says that Crispio was Epiphaniusís archdeacon.

It is evident, therefore, that the brothers were of Alaphionís family. Alaphion, too, was related to Sozomenís grandfather, as we may conjecture; first, because the grandfather of Sozomen is said to have been converted (together with his whole family) to the Christian religion, upon account of Alaphionís wonderful cure, whom Hilarion had healed by calling on the name of Almighty God. Secondly, this conjecture is confirmed by what Sozomen relates, viz., that when he was very young, he conversed familiarly with the aged monks that were of Alaphionís family. And, lastly, from the fact that Sozomen took his name from those persons who were either the sons or grandchildren of Alaphion.

For he was called Salamanes Hermias Sozomenus (as Photius declares in his Bibliotheca), from the name of that Salamanes who, as we observed before, was the brother of Phusco, Malchio, and Crispio. Wherefore Nicephorus, and others, are mistaken in supposing that Sozomen had the surname of Salaminius because he was born at Salamis, a city of Cyprus. But we have before shown from Sozomenís own testimony, that he was not born in Cyprus, but in Palestine. For his grandfather was not only a Palestinian, as is above said, but Sozomen himself was also educated in Palestine, in the bosom (so to say) of those monks who were of Alaphionís family.

From this education Sozomen seems to have imbibed that most ardent love of a monastic life and discipline, which he declares in so many places of his history. Hence it is, that in his books he is not content to relate who were the fathers and founders of monastic philosophy; but he also carefully relates their successors and disciples, who followed this way of life both in Egypt, Syria, and Palestine, and also in Pontus, Armenia, and OsdroŽna. Hence also it is, that in the twelfth chapter of the first book of his history, he has proposed to be read (in the beginning as it were) that gorgeous account of the monastic philosophy.

For he supposed that he should have been ungrateful, had he not after this manner at least made a return of thanks to those in whose familiarity he had lived, and from whom, when he was a youth, he had received such eminent examples of a good conversation, as he himself intimates, in the opening of his first book. It is inferred that Sozomen was educated at Gaza, not only from the passage above mentioned, but also from chap. xxviii. of his seventh book, where Sozomen says that he himself had seen Zeno, bishop of Majuma, for this Majuma is a sea-port belonging to the Gazites. Although Zeno was nearly a hundred years old, he was never absent from the morning and evening hymns, unless sickness detained him.

After this Sozomen applied himself to the profession of the law. He was a student of the civil law at Berytus, a city of Phoenicia, not far distant from his own country, where there was a famous school of civil law. But he practiced the law at Constantinople, as himself asserts, book ii. chap. iii. And yet he seems not to have been very much employed in pleading of causes; for at the same time that he was an advocate in Constantinople, he wrote his Ecclesiastical History - Historia Ecclesiastica; as may be concluded from his own words in the last-mentioned passage.

Before he wrote his nine books of Ecclesiastical History, Sozomen composed a Breviary of Ecclesiastical Affairs, from our Saviourís ascension to the deposition of Licinius. This work was comprised in two books, as himself bears witness in the opening of his first book; but these two books are now lost. In the composure of his History, Sozomen has made use of a style neither too low nor too high, but one between both, as is most agreeable to a writer of ecclesiastical affairs.

Photius prefers Sozomenís style to that of Socrates, and we agree with him in his criticism. But though Sozomen is superior in the elegance of his expression, yet Socrates excels him in judgment. For Socrates judges incomparably well, both of men, and also of ecclesiastical business and affairs; and there is nothing in his works but what is grave and serious, nothing that can be expunged as superfluous. But on the contrary, some passages occur in Sozomen that are trivial and childish. Of this sort is his digression in his first book concerning the building of the city Hemona, and concerning the Argonauts, who carried the ship Argo on their shoulders some furlongs, and also his description of Daphne without the walls of the city Antioch, in chap. xix. of his sixth book; to which we must add that observation of his, concerning the beauty of the body, where he treats of that virgin at whose house the blessed Athanasius was concealed a long while. Lastly, his ninth book contains little else besides warlike events, which ought to have no place in an Ecclesiastical History. Sozomenís style, however, is not without its faults.

For the periods of his sentences are only joined together by the particles de and te, than which there is nothing more troublesome. Should any one attentively read the epistle in which Sozomen dedicates his work to Theodosius junior, he will find it true that Sozomen was no great orator. It remains, that we inquire which of these two authors, Socrates or Sozomen, wrote first, and which of them borrowed, or rather stole, from the other.

Certainly, since both of them wrote almost the same things of the same transactions, inasmuch as they both began at the same beginning, and concluded their history at the same point (both beginning from the reign of Constantine, and ending at the seventeenth consulate of Theodosius junior), it must needs be true, that one of them robbed the otherís desk. This sort of theft was committed by many of the Grecian writers, as Porphyry testifies, Eusebiusí* Praeparatio Evangelica, bk. x. But which was the plagiary, Socrates or Sozomen, it is hard to say, in regard both of them lived in the same times, and both wrote their history in the empire of Theodosius junior.

Therefore, in the disquisition of this question, we must make use of conjecture. So Porphyry in the above-mentioned book, since it was uncertain whether Hyperides had stolen from Demosthenes, or Demosthenes from Hyperides, because both had lived in the same time, decided to use conjecture. Let us therefore see upon which of them falls the suspicion of theft. Indeed, this is my sentiment, I suppose that the inferior does frequently steal from the superior, and the junior from the senior.

But Sozomen is in my judgment far inferior to Socrates; and he betook himself to writing his history when he was younger than Socrates. For he wrote it whilst he was yet an advocate, as I observed before. Now, the profession of the advocates amongst the Romans was not perpetual, but temporary. Lastly, he that adds something to the other, and sometimes amends the other, seems to have written last. But Sozomen now and then adds some passages to Socrates, and in some places dissents from him, as Photius has observed, and we have hinted in our annotations. Sozomen therefore seems to have written last. And this is the opinion of almost all modern writers, who place Socrates before Sozomen. So Bellarmine in his book De Scriptoribus Ecclesiasticis; who is followed by Miraeus, Labbaeus, and Vossius. Amongst the ancients, Cassiodorus, Photius, and Nicephorus name Socrates in the first place.

Although Cassiodorus is found to have varied; for in the preface of the Tripartite History, he inverts the order, and names Theodoret first, ranks Sozomen in the second place, and refers to Socrates as the last. So also Theodorus Lector recounts them in his epistle which he prefixed to his Tripartite History. Thus far concerning Sozomen.

www.ccel.org