Lessico

Gemelli & Gemelli

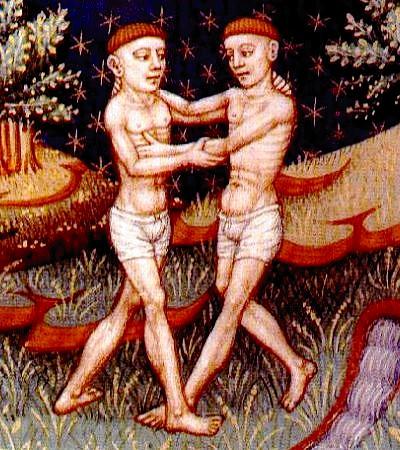

I Gemelli in un libro di astrologia del XV secolo

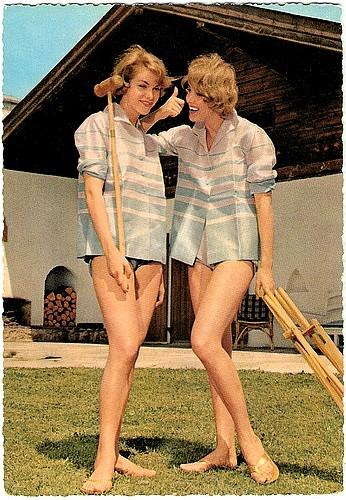

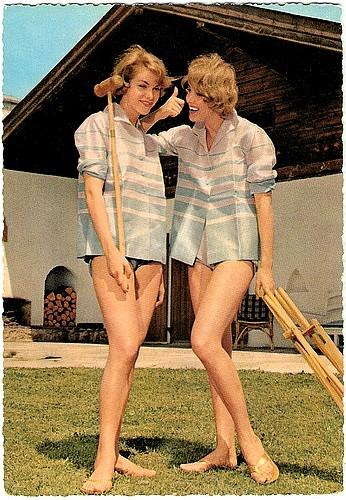

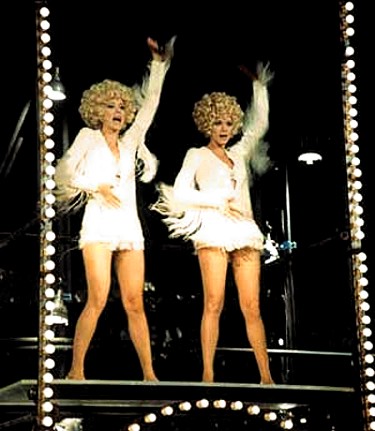

Le gemelle Kessler

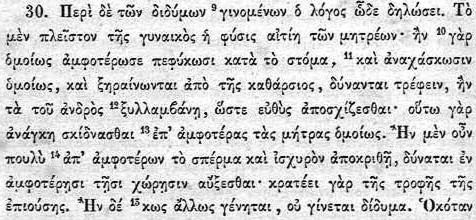

De

victus ratione

La dieta - I,30

Da

natura pueri

La natura del bambino - IV,31

Hippocrate

- Oeuvres complètes

par Émile Littré - Paris 1851

Historia

animalium

traduzione e note di Mario Vegetti

VI,19: Sia le pecore sia le capre effettuano e accettano la monta per tutta la vita. Condizioni perché le une e le altre diano alla luce gemelli sono l’abbondanza di cibo, e che il montone o il capro oppure la rispettiva femmina fossero a loro volta gemelli*.

* La constatazione dell’ereditarietà del parto gemellare è esatta, e forse Aristotele si riferisce qui a tecniche di allevamento selettivo già in uso in Grecia. AT non ha compreso questo passo, che invece Schneider rende bene: «cum aries aut hircus vel ipsa mater fuerit una e gemellis».

VII,4: Vi è dunque, fra l’uomo e gli altri animali, questa differenza relativa alla varietà dei periodi nei quali la gestazione umana può essere portata a termine. E mentre alcuni animali sono unipari, altri multipari, il genere umano partecipa delle caratteristiche di entrambi i gruppi. Di solito infatti e nella maggior parte dei paesi le donne partoriscono un solo figlio, spesso però e in molte regioni danno alla luce gemelli, come accade ad esempio in Egitto. Ne generano anche tre o quattro, in certi luoghi ben definiti, come s’è detto prima. Al massimo vengono dati alla luce cinque figli: questo fatto è già stato osservato e in più di un caso. Una donna partorì venti figli in quattro parti, dandone alla luce cinque per volta, e la maggior parte di essi poté svilupparsi. Negli altri animali, comunque, anche se i gemelli sono l’uno maschio e l’altro femmina, possono crescere e sopravvivere [585a] non meno che se fossero entrambi maschi o femmine; nell’uomo invece pochi gemelli si salvano se l’uno è femmina e l’altro maschio. Fra gli animali sono soprattutto la donna e la cavalla ad accettare il coito durante la gestazione; le altre femmine fuggono il maschio quando sono gravide, quelle s’intende che non sono naturalmente predisposte alla superfetazione come la lepre. Ma la cavalla, quando ha concepito una prima volta, non può esser nuovamente fecondata per superfetazione, anzi genera per lo più un solo puledro; nell’uomo, benché raramente, si ha tuttavia qualche caso di superfeta-zione. Comunque i concepimenti che hanno luogo molto tempo dopo il primo non giungono a termine, bensì provocano sofferenze e coinvolgono nella propria distruzione l’embrione preesistente (è accaduto che in seguito a questa distruzione fossero espulsi persino dodici feti concepiti per superfetazione). Se invece il concepimento segue immediatamente il primo, la donna porta a compimento anche questo secondo prodotto, e lo dà alla luce come in un parto gemellare: è proprio quanto racconta il mito di Ificle e di Eracle. [Figli entrambi di Alcmena, ma generato il primo da Anfitrione, il secondo da Zeus.] Ed è anche accaduto questo caso illuminante: una donna adultera diede alla luce due gemelli, di cui uno assomigliava al marito, l’altro all’amante. Un’altra, già incinta di due gemelli, concepì un terzo figlio per superfetazione, e quando giunse il momento debito partorì i gemelli ben portati a termine, il terzo invece di cinque mesi (e questo morì subito). E a un’altra donna ancora accadde, dopo aver generato un primo figlio di sette mesi, di partorirne due al termine dello sviluppo: di essi il primo perì, gli altri sopravvissero.

VII,6: Quanto ai gemelli, è avvenuto che ne nascessero non somiglianti tra loro, ma per la maggior parte e per lo più si assomigliano. Vi sono certe donne che tendono a dare alla luce figli somiglianti a se stesse, altre invece al marito, come la cavalla di Farsalo che chiamavano «la giusta».

de

Generatione animalium

traduzione di Diego Lanza

IV,1: Ma, anche se il caldo e il freddo fossero la causa della differenza di queste parti, occorreva che i sostenitori di questa dottrina la spiegassero, perché questo è in un certo senso spiegare la generazione di maschio e femmina; per queste parti infatti la differenza è manifesta. Non è impresa trascurabile, partendo da questo principio, cogliere la causa della formazione di queste parti; per necessaria conseguenza infatti la parte chiamata utero si formerebbe nell’animale sottoposto a raffreddamento, mentre quando l’animale fosse riscaldato non si formerebbe. Lo stesso sarebbe delle parti che compiono la copula, perché anch’esse, come già si è detto, differiscono. Inoltre spesso si formano contemporaneamente nella stessa parte dell’utero una femmina e un maschio gemelli, e ciò si è osservato a sufficienza in tutti i vivipari, terrestri e pesci, in séguito alle dissezioni. Se dunque Empedocle non ha fatto queste osservazioni è logico che si sia sbagliato adducendo questa causa, se invece le osservazioni le ha fatte è assurdo che tuttavia ritenga essere [764b] il freddo e il caldo la causa dell’utero, perché entrambi i gemelli nascerebbero o femmine o maschi, mentre vediamo che questo non accade. E poiché sostiene che le parti dell’essere che sta nascendo sono divise (le une infatti egli afferma essere nel maschio, le altre nella femmina, e perciò vi è il desiderio di unirsi reciprocamente), sarebbe necessario che l’elemento corporeo anche di queste parti fosse diviso e avvenisse una confluenza ma non per effetto di raffreddamento o riscaldamento.

IV,4: Democrito afferma che le anomalie sono dovute a una doppia immissione di sperma, una che penetra prima, l’altra dopo, anch’essa che giunge direttamente all’utero, sì che le parti si formano insieme e si trasformano. Ma se accade che da un unico seme e un’unica copula [770a] nascano in più, e ciò si è ben osservato, è meglio non girare in tondo avendo lasciato il cammino diretto, perché in tali casi è necessario che accada questo, quando i semi non siano separati, ma procedano insieme. Se dunque si deve attribuire la causa di ciò allo sperma del maschio, si deve dirlo in questo modo. Ma in generale si deve piuttosto pensare che la causa stia nella materia e negli embrioni quando si costituiscono. Perciò siffatte anomalie si producono assai raramente negli unipari, e più nei multipari e soprattutto negli uccelli, e tra gli uccelli nei polli. Questi non sono solo multipari perché depongono spesso uova, come il genere dei colombi, ma perché portano contemporaneamente molti prodotti del concepimento, e si accoppiano in ogni stagione. Perciò producono molti gemelli: i prodotti del concepimento grazie alla reciproca vicinanza si formano insieme, come molti frutti fanno talvolta. In tutti quelli che hanno i tuorli definiti dalla membrana nascono due piccoli separati senza alcuna superfetazione, mentre in quelli che hanno i tuorli contigui e senza alcuna interruzione i piccoli nascono anomali con un corpo e una testa, ma quattro gambe e quattro ali, perché le parti superiori dell’animale si formano prima e dal bianco, essendo controllato il loro alimento proveniente dal tuorlo, mentre la parte inferiore si forma dopo e l’alimento è unico e indistinto. È accaduto di vedere anche un serpente a due teste per la stessa causa, perché anche questo genere è oviparo e multiparo. Le anomalie sono però più rare in essi per la configurazione dell’utero. Data la sua dimensione la massa delle uova si trova infatti disposta in fila. Non accade nulla del genere né alle api né alle vespe, perché la loro nascita avviene in cellule separate. Nel caso dei polli avviene invece l’opposto, e anche in questo caso è chiaro che la causa di questi fenomeni deve essere attribuita alla materia, perché anche tra gli altri animali si hanno soprattutto nei multipari. Ecco perché ce n’è di meno nell’uomo, perché egli è per lo più uniparo e genera prole compiuta. L’anomalia è presente di più nelle regioni, come l’Egitto, in cui le donne sono molto prolifiche. Si ha anche più tra le capre e le pecore, perché sono più prolifiche. Ma ancora di più nei polidattili: siffatti animali sono multipari e non generano prole compiuta, come il cane [770b] che partorisce la maggior parte della prole cieca. Si dovrà spiegare in séguito per quale causa questo accade e per quale causa sono multipari. Essi sono predisposti per natura a generare prole anomala perché non la generano simile a sé data la sua incompiutezza, e anche l’anomalo fa parte dei non simili. Perciò questa coincidenza negli animali di natura siffatta si ha in modo intermittente, ed è anche tra questi che nascono soprattutto i cosiddetti «ultimi venuti».

IV,4: La stessa causa vale per le parti in eccesso contro natura e per il parto gemellare. La causa è già presente nei prodotti del concepimento qualora si concentri più materia di quella che è conforme alla natura della parte. Talvolta infatti accade di avere una parte più grande delle altre, come per esempio un dito, una mano, un piede o un’altra estremità o membro, oppure, scissosi il prodotto del concepimento, se ne formano più, come i vortici nei fiumi. Anche in questo caso, se il fluido portato e recante in sé un impulso trova un ostacolo, da una condensazione se ne formano due dotate dello stesso impulso. Nello stesso modo accade anche per i prodotti del concepimento. Il più delle volte si trovano attaccati l’uno vicino all’altro, ma talvolta anche lontano per il movimento che si sviluppa nel prodotto del concepimento, e soprattutto perché l’eccedenza di materia è riportata dove è stata tolta e serba la forma della parte donde si è sviluppata in eccesso.

IV,6: Per la causa che si è detta nell’uomo i gemelli, uno maschio l’altro femmina, sopravvivono meno, mentre negli altri animali non vi è differenza. Nel primo infatti il procedere con la stessa velocità sarebbe contrario a natura, giacché il processo di distinzione non si svolge in tempi uguali, ma il maschio deve necessariamente essere in ritardo o la femmina in anticipo, mentre negli altri animali non è contro natura.

Gemello deriva dal latino gemellus, diminutivo di geminus, doppio. I gemelli si distinguono in monovulari (o monozigotici) e in diovulari (o dizigotici). I monovulari posseggono, di norma, gli stessi annessi embrionali, ed è questo il primo criterio di giudizio, unitamente all'identità di sesso, per la loro distinzione immediata. Infatti, i gemelli monovulari derivano dalla stessa cellula uovo fecondata, la quale si divide ai primi stadi embrionali, dando così origine a due individui separati ma geneticamente identici. Nel caso dei gemelli diovulari si hanno invece due fecondazioni quasi contemporanee di due diverse cellule uovo da parte di due spermi.

Le indagini sui gemelli presentano un elevato interesse in genetica umana, costituendone addirittura uno dei metodi di studio più importanti. È infatti possibile studiare l'importanza della componente ereditaria e di quella ambientale nell'estrinsecazione dei caratteri. Così, in gemelli dizigotici dello stesso sesso e allevati insieme si è potuto constatare che le caratteristiche fisiche sono le meno influenzate dall'ambiente, mentre le capacità mentali mostrano un'elevata dipendenza da questo.

I gemelli monozigotici, separati subito dopo la nascita, possono invece dare

utili indicazioni sull'influenza dell'ambiente nel determinare differenze

individuali. L'incidenza dei parti gemellari è di ca. uno su 88, e ca. 1/4 di

questi è monovulare. Le nascite trigemellari sono ca. una su 7000 e quelle

tetragemellari una su 780.000. La nascita di gemelli in alcune specie di

Mammiferi non è un avvenimento raro (p. es. bovini) e in altre è di regola:

l'armadillo comune![]() , Dasypus

novemcinctus, partorisce

sempre quattro piccoli. L'armadillo meridionale, Dasypus hybridus,

addirittura partorisce in media 8 gemelli monovulari, con valori che possono

oscillare da 7 a 12. La costellazione dei Gemelli

, Dasypus

novemcinctus, partorisce

sempre quattro piccoli. L'armadillo meridionale, Dasypus hybridus,

addirittura partorisce in media 8 gemelli monovulari, con valori che possono

oscillare da 7 a 12. La costellazione dei Gemelli![]() è tutt'altra cosa.

è tutt'altra cosa.

Twin comes from old English twinn "consisting of two, twofold, double." Multiple births are rare among human beings and other large mammals. More than 98 percent of all human pregnancies result in single offspring; multiple births, which account for the rest, occur with rapidly decreasing frequency the higher the multiple. An increase in the number of such births has been observed, however, since the introduction of so-called fertility drugs in the 1960s. These hormonal drugs tend to cause polyovulation in women -- the release of more than one egg at a time for fertilization. Almost all higher-multiple pregnancies result in premature babies. Without such drugs, older women are more likely to have multiple pregnancies than younger women, and for individual women such pregnancies are more likely to occur later in the birth order.

Multiple births may be identical, fraternal, or (in cases other than twins) some combination of these. Identical births are monozygotic; that is, they arise from a single fertilized egg (zygote) that at some stage in its development separates into two or more embryos. (Siamese Twins*. result from very late or incomplete division.) Such births share the same genetic material and are always of the same sex.

Fraternal births are polyzygotic; they arise from two or more fertilized eggs and may be of either sex. The famous Dionne quintuplets of Canada, born in 1934, were monozygotic, but almost all recent higher-multiple births have been polyzygotic because they were caused by fertility drugs.

Because identical twins are genetically equivalent and are also relatively common, compared to higher-multiple births, they have been frequent subjects of study in such fields as behavioral genetics and intelligence research. These studies seek to learn more about the relative importance of cultural and genetic influences in determining the characteristics of individuals.

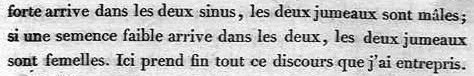

Chang e Eng Bunker

Si tratta di una coppia di individui dello stesso sesso, ugualmente sviluppati ma congiunti per una parte del corpo, dei quali in qualche caso è possibile la separazione chirurgica. L'evento dipende dalla divisione incompleta dell'embrione e la coppia è sempre monozigote e dello stesso sesso con impronte digitali e gruppo sanguigno uguali.

Le cause dell'incompleta scissione al momento non sono scientificamente accertate ma si ipotizza che sia influenzato da alcuni fattori ambientali e dall'attivazione di determinati programmi genici (ma non sembra essere un carattere ereditario). La nascita di gemelli siamesi è un'eventualità molto rara, circa 1:120.000, e spesso porta a morti premature a causa delle malformazioni degli organi interni. Le tipologie cambiano a seconda delle parti in cui sono uniti e degli organi che hanno in comune: solitamente si dividono in quelle che non coinvolgono il cuore e l'ombelico e quelle che coinvolgono l'ombelico. A parte, sono classificate quelle anomale, in cui uno dei due embrioni è malformato o interno all'altro.

Anche in epoca moderna, non sempre è possibile separare i due corpi, come dimostra il caso di Ladan e Laleh Bijani, morte durante l'intervento per separarle. Un caso divenuto storico, che fece il giro del mondo, fu la vicenda delle gemelle Foglia, due bambine piemontesi nate unite per il bacino nel 1958 e separate il 10 maggio 1965 all'ospedale Regina Margherita di Torino, con un intervento chirurgico sbalorditivo per quell'epoca, il primo effettuato con successo in Europa. A eseguire l'intervento il professor Luigi Solerio, assistito da 24 medici.

Nel X secolo Leone Diacono, storico bizantino nato nel 950, fu il primo a descrivere un caso di gemelli congiunti. Nell'antichità e nel medioevo la nascita dei gemelli congiunti era collegata alle cause più disparate: interventi del diavolo, tipo di alimentazione, posizione della donna durante la gravidanza ecc. Il termine "siamese" deriva dal caso più celebre, quello di Chang e Eng Bunker, gemelli nati nel Siam (l'attuale Thailandia) l'8 maggio1811, uniti al torace da una striscia di cartilagine. I loro nomi possono essere tradotti nella nostra lingua rispettivamente come Sinistro e Destro. Chang e Eng Bunker, dopo essere emigrati negli Stati Uniti, lavorarono a lungo nel circo Barnum: sposarono due sorelle, ebbero 22 figli e vissero fino all'età di 62 anni, essendo morti il 17 gennaio 1874. Ronnie e Donnie Galyon, dell'Ohio, sono nati nel 1951 e attualmente sono la coppia di gemelli siamesi viventi più vecchia del mondo, nonché l'unica di maschi adulti. Nel 1981 hanno recitato nel film "Being Different".

Grave of Eng and Chang Bunker near Mt. Airy, North Carolina

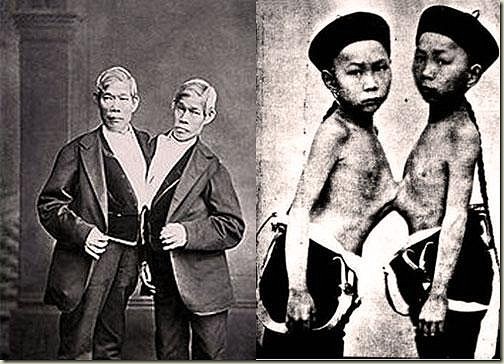

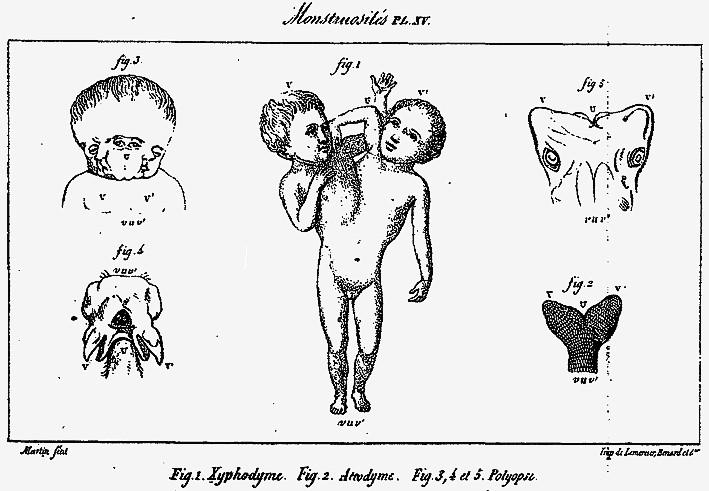

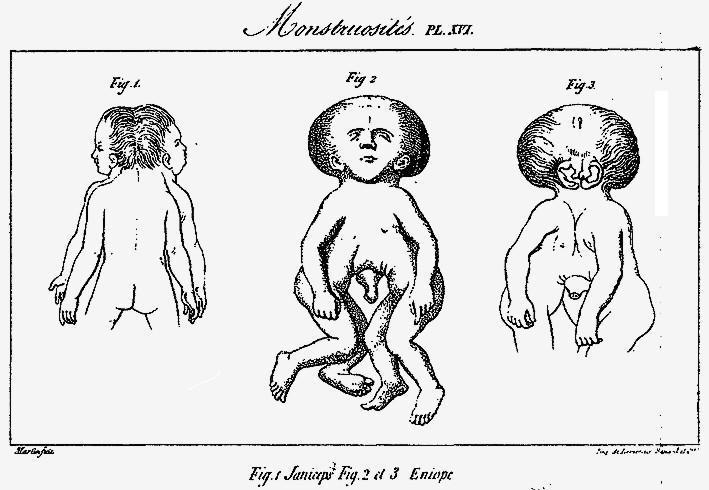

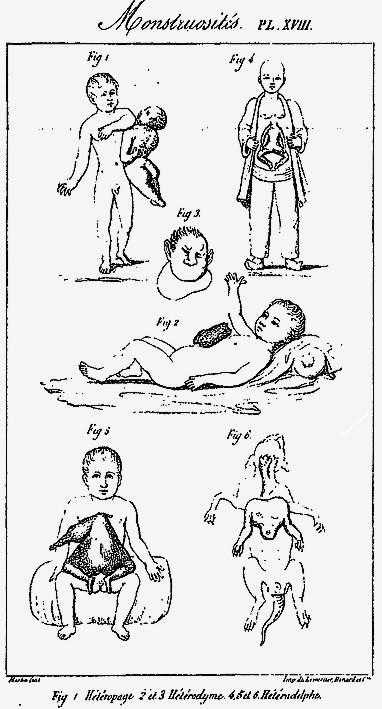

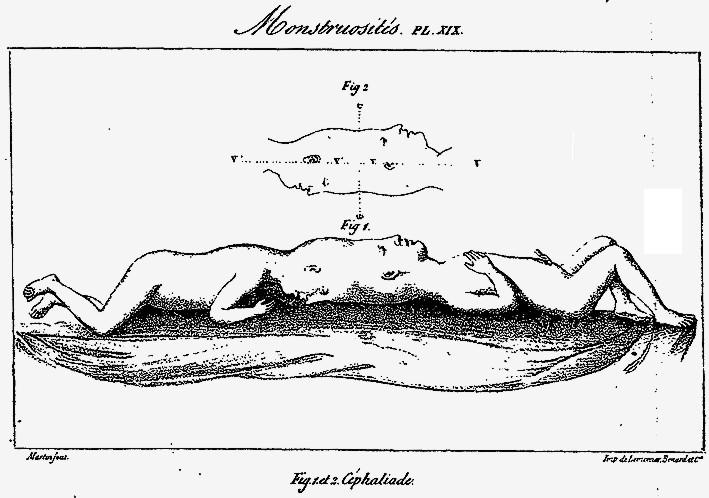

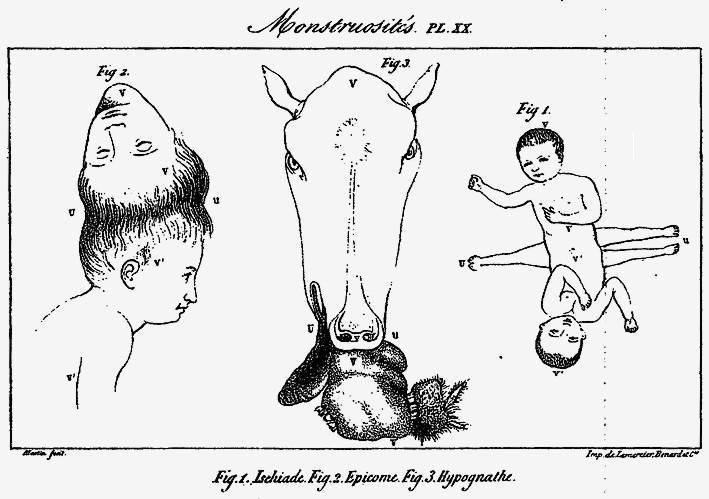

Geoffroy St. Hillaire

Histoire générale et particulière

des anomalies de l'organisation chez l'homme et chez les animaux

Tome 3

JB. Baillière

- Paris 1837

Siamese twins

Conjoined twins

Chang and Eng Bunker

Conjoined/Siamese twins are identical twins or non identical whose bodies are joined in uterus. A rare phenomenon, the occurrence is estimated to range from 1 in 50,000 births to 1 in 200,000 births, with a somewhat higher incidence in Southwest Asia and Africa. Approximately half are stillborn, and a smaller fraction of pairs born alive have abnormalities incompatible with life. The overall survival rate for conjoined twins is approximately 25%. The condition is more frequently found among females, with a ratio of 3:1.

Two contradicting theories exist to explain the origins of conjoined twins. The older and most generally accepted theory is fission, in which the fertilized egg splits partially. The second theory is fusion, in which a fertilized egg completely separates, but stem cells (which search for similar cells) find like-stem cells on the other twin and fuse the twins together.

The most famous pair of conjoined twins was Chang and Eng Bunker (May 5th 1811 – January 17th 1874), Thai brothers born in Siam, now Thailand. They traveled with P.T. Barnum's circus for many years and were billed as the Siamese Twins. Chang and Eng were joined by a band of flesh, cartilage, and their fused livers at the thorax. In modern times, they could have been easily separated. Due to the brothers' fame and the rarity of the condition, the term came to be used as a synonym for conjoined twins.

Conjoined twins are typically classified by the point at which their bodies are joined. The most common types of conjoined twins are:

Thoraco-omphalopagus (28% of cases): Two bodies fused from the upper chest to the lower chest. These twins usually share a heart, and may also share the liver or part of the digestive system.

Thoracopagus (18.5%): Two bodies fused from the upper thorax to lower belly. The heart is always involved in these cases.

Omphalopagus (10%): Two bodies fused at the lower chest. Unlike thoracopagus, the heart is never involved in these cases; however, the twins often share a liver, digestive system, diaphragm and other organs.

Parasitic twins (10%): Twins that are asymmetrically conjoined, resulting in one twin that is small, less formed, and dependent on the larger twin for survival.

Craniopagus (6%): Fused skulls, but separate bodies. These twins can be conjoined at the back of the head, the front of the head, or the side of the head, but not on the face or the base of the skull. Other less-common types of conjoined twins include:

Cephalopagus: Two faces on opposite sides of a single, conjoined head; the upper portion of the body is fused while the bottom portions are separate. These twins generally cannot survive due to severe malformations of the brain. Also known as janiceps (after the two-faced god Janus) or syncephalus.

Synencephalus: One head with a single face but four ears, and two bodies.

Cephalothoracopagus: Bodies fused in the head and thorax. In this type of twins, there are two faces facing in opposite directions, or sometimes a single face and an enlarged skull.

Xiphopagus: Two bodies fused in the xiphoid cartilage, which is approximately from the navel to the lower breastbone. These twins almost never share any vital organs, with the exception of the liver. A famous example is Chang and Eng Bunker.

Ischiopagus: Fused lower half of the two bodies, with spines conjoined end-to-end at a 180° angle. These twins have four arms; two, three or four legs; and typically one external genitalia and anus.

Omphalo-Ischiopagus: Fused in a similar fashion as ischiopagus twins, but facing each other with a joined abdomen akin to omphalopagus. These twins have four arms, and two, three, or four legs.

Parapagus: Fused side-by-side with a shared pelvis. Twins that are dithoracic parapagus are fused at the abdomen and pelvis, but not the thorax. Twins that are diprosopic parapagus have one trunk and one head with two faces. Twins that are dicephalic parapagus have one trunk and two heads, and two (dibrachius), three (tribrachius), or four (tetrabrachius) arms.

Craniopagus parasiticus: Like craniopagus, but with a second bodiless head attached to the dominant head.

Pygopagus (Iliopagus): Two bodies joined back-to-back at the buttocks.

Surgery to separate conjoined twins may range from relatively simple to extremely complex, depending on the point of attachment and the internal parts that are shared. Most cases of separation are extremely risky and life-threatening. In many cases, the surgery results in the death of one or both of the twins, particularly if they are joined at the head. This makes the ethics of surgical separation, where the twins can survive if not separated, contentious. Dreger found the quality of life of twins who remain conjoined to be higher than is commonly supposed. Lori and George Schappell are a good example.

A case of particular interest was that of Mary and Jodie, two conjoined twins from Malta who were separated by court order in Great Britain over the religious objections of their parents, Michaelangelo and Rina Attard. The surgery took place in November, 2000, at St Mary's Hospital in Manchester. The operation was controversial because it was certain that the weaker twin, Mary, would die as a result of the procedure. (The twins were attached at the lower abdomen and spine; Jodie's heart and lungs supplied both of their bodies.) However, if the operation had not taken place, it was certain that both twins would die.

The Moche culture of ancient Peru depicted conjoined twins in their ceramics dating back to CE 300. The earliest known documented case of conjoined twins dates from the year 945, when a pair of conjoined twin brothers from Armenia were brought to Constantinople for medical evaluation. It was here that they were determined to be acts of God and the birth of conjoined twins was considered a proof that the male's sexual prowess was truly twice that of the average man.

The English twin sisters Mary and Eliza Chulkhurst, who were conjoined at the back (pygopagus), lived from 1100 to 1134 and were perhaps the best-known early historical example of conjoined twins. Other early conjoined twins to attain notice were the "Scottish brothers", allegedly of the dicephalus type, essentially two heads sharing the same body (1460–1488, although the dates vary); the pygopagus Helen and Judith of Szőny, Hungary (1701–1723), who enjoyed a brief career in music before being sent to live in a convent; and Rita and Cristina of Parodi of Sardinia, born in 1829. Rita and Cristina were dicephalus tetrabrachius (one body with four arms) twins and although they died at only eight months of age, they gained much attention as a curiosity when their parents exhibited them in Paris.

Several sets of conjoined twins lived during the nineteenth century and made careers for themselves in the performing arts, though none achieved quite the same level of fame and fortune as Chang and Eng. Most notably, Millie and Christine McCoy (or McKoy), pygopagus twins, were born into slavery in North Carolina in 1851. They were sold to a showman, J.P. Smith, at birth, but were soon kidnapped by a rival showman. The kidnapper fled to England but was thwarted because England had already banned slavery. Smith traveled to England to collect the girls and brought with him their mother, Monimia, from whom they had been separated. He and his wife provided the twins with an education and taught them to speak five languages, play music, and sing. For the rest of the century the twins enjoyed a successful career as "The Two-Headed Nightingale" and appeared with the Barnum Circus. In 1912 they died of tuberculosis, 17 hours apart.

Giovanni and Giacomo Tocci, from Locana (TO), Italy, were immortalized in Mark Twain's short story "Those Extraordinary Twins" as fictitious twins Angelo and Luigi. The Toccis, born in 1877, were dicephalus tetrabrachius twins, having one body with two legs, two heads, and four arms. From birth they were forced by their parents to perform and never learned to walk, as each twin controlled one leg (in modern times physical therapy allows twins like the Toccis to learn to walk on their own). They are said to have disliked show business. In 1886, after touring the United States, the twins returned to Europe with their family, where they fell very ill. They are believed to have died around this time, though some sources claim they survived until 1940, living in seclusion in Italy.

List of conjoined twins

Born 19th century and earlier

Mary and Eliza Chulkhurst (1100-1134) (also known as the Biddenden Maids) from England. They are the earliest set of conjoined twins whose names are known.

Lazarus and Joannes Baptista Colloredo (1617-164?)

Helen and Judith of Szony (Hungary, 1701–1723)

Chang and Eng Bunker (1811-1874), from Thailand (formerly Siam), joined by the areas around their xiphoid cartilages, but over time the join stretched; the expression Siamese twins is derived from their case.

Millie and Christine McCoy (July 11, 1851 - 1912) were American conjoined twins who went by the stage names "The Two-Headed Nightingale" and "The Eighth Wonder of the World".

Rosa and Josepha Blazek of Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic (1878–1922));

Radica and Doodica were born in Orissa, India in 1888. They were xiphopagus twins, joined at the chest by a band of cartilage, similar to Chang and Eng. The sisters were separated in Paris by Dr. Eugène-Louis Doyen with the hope of saving Radica. Dr. Doyen was a pioneering medical filmmaker and filmed the twins' surgery as La Séparation de Doodica-Radica. Though the operation was considered a success at first, Doodica died shortly after separation, and Radica also succumbed to tuberculosis in 1903, having lived the last year of her life in a Paris sanatorium.

Born 20th century

Daisy and Violet Hilton of Brighton, East Sussex, England (1908–1969), born in England, lived in United States, actresses, appeared in the movies Freaks and Chained for Life.

Lucio and Simplicio Godina of Samar, Philippines (1908–1936).

Mary and Margaret Gibb of Holyoke, Massachusetts (1912–1967).

Yvonne and Yvette McCarther of Los Angeles, California (1949–1992).

Masha and Dasha Krivoshlyapova (ischiopagus tripus) Moscow, Russia (1950-2003), Soviet/Russian twin girls, rarest form of conjoined twins, only known case of dicephalus tetrabrachius tripus (two heads, four arms, three legs). The third, fused leg was amputated when the twins were 16 or 17.

Lotti and Rosemarie Knaack (craniopagus) born in Hamburg, Germany in 1951. Craniopagus. Separated in 1957 when they were nearly six years old. Lotti died in surgery.

Ronnie and Donnie Galyon of Ohio (1951–), currently the world's oldest living conjoined twins.

Lori and George (formerly Reba, born Dori) Schappell born 18 September 1961 in Reading, Pennsylvania, American entertainers, craniopagus, not separated.

Sherrie and Sharise Jones born on June 15, 1967 and successfully separated on November 13, 1968 in Brooklyn, New York, ischiopagus tripus conjoined twins.

Ladan and Laleh Bijani of Shiraz, Iran (Persia) (1974–2003); died during separation surgery in Singapore.

Viet and Duc Nguyen, born on February 25, 1981 in Kon Tum Province, Tây Nguyên, Vietnam, and separated on October 4, 1988 in Ho Chi Minh City. Viet died on October 6, 2007.

Ruthie and Verena Cady, born April 13, 1984, thoracopagus twins. Died of heart and respiratory problems July 19, 1991.

Katie and Eilish Holton of Kildare, babies born joined at the shoulder in 1988. Separation became a necessity; Katie died shortly after the procedure was performed.

Abigail and Brittany Hensel, (1990-), born in Carver County, Minnesota, United States of America, dicephalic conjoined twins, two heads, two arms, two legs, cannot be separated.

Ram & Laxman 1992 Successfully separated st Guntur, India.

Anjali & Geetanjali 1993 Successfully separated st Guntur, India.

Rekha & Surekha 1998 Successfully separated st Guntur, India.

Shawna and Janelle Roderick (thoracopagus) separated May 31, 1996 at Loma Linda Children's Hospital.

Born 21st century

Ayşe and Sema born in Kahramanmaraş, Turkey on December 24, 2000 with 2 heads, 4 arms and 2 legs.

Carmen and Lupita Andrade, born Dicephalus Tetrabrachius Dipus (2 heads, 4 arms and 2 legs) in 2000. Separation was not possible.

Ganga and Jamuna Shreshta of Nepal, conjoined twins born May 9, 2000 who were separated in a landmark surgery in Singapore in 2001; Ganga died on July 29 2008 at the age of 8 of a chest infection.

Mohamed and Ahmed Ibrahim, born in a small Egyptian town on June 2, 2001, separated in a 34-hour operation at Children's Medical Center Dallas on October 12, 2003.

Rose and Grace Attard ("Mary and Jodie"), Maltese twins joined at spine, born October 2000. Separated in Great Britain by court order against the wishes of their parents, because Mary could not survive independently. Mary died upon separation.

Lexi and Syd Stark Born in 2001, successfully separted later.

Sarah and Abbey (Pygopagus) born in New Zealand in 2004 and separated successfully later that year.

Veena & Vani 2004 Successfully separated in Guntur, India.

Leah & Tabea B. born in 2003 in Lemgo/Germany, conjoined at the head, separated in Baltimore in 2004. Tabea died shortly afterwards.

Lakshmi Tatma (born 2005) was an ischiopagus conjoined twin born in Araria district in the state of Bihar, India. She had four arms and four legs, resulting from a joining at the pelvis with a headless undeveloped parasitic twin. Some of the local villagers have hailed her as the reincarnation of Lakshmi, the multi-limbed Hindu goddess. In November 2007 she successfully underwent surgery to remove the parasitic twin.

Jade and Erin Buckles, born February 26, 2004, United States. Separated in June 2004.

Kendra and Maliyah Herrin ischiopagus twins separated in 2006 at age 4. Born with only one kidney between the two, Maliyah received a kidney transplant from her mother in 2007. The twins' mother then wrote a book about her experiences titled "When Hearts Conjoin", the only book about conjoined twins written by a parent of conjoined twins.

Krista and Tatiana Hogan, Canadian twins conjoined at the head. Born October 25, 2006.

Faith and Hope Williams born in London, England, on 26 November 2008; The girls were joined from the breastbone to the navel. On 2 December 2008 they underwent an operation to separate them at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London. On 3 December Hope died. Faith died 23 days after her sister on Christmas Day, with her parents at her bedside.

Alex and Angel Mendoza were born in the summer of 2008 and were joined from below their sternums to their pelvises. They were successfully separated in January 2009.

Jayden and Joshua Chamberlain were born in July 2009 in London, joined face to face with a shared liver and fused heart. Joshua was stillborn and Jayden died 30 minutes after the birth. Separation was previously considered too risky to undertake due to the extent at which the boys' hearts were connected.

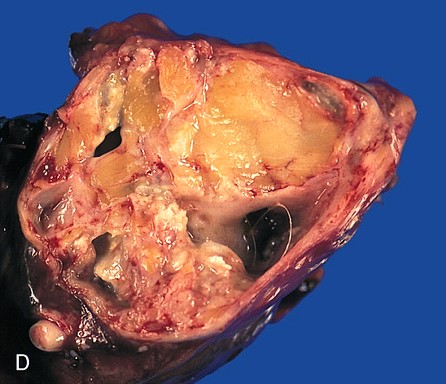

Teratoma mediastinico

Si noti la presenza di diversi tessuti anaplastici e

annessi (peli)

Il termine deriva dal greco téras, genitivo tératos = mostro, prodigio, portento. Si tratta di una neoplasia composta da una varietà di tipi di cellule rappresentanti di solito tutti e tre i foglietti germinali (ectoderma, mesoderma, endoderma); deriva normalmente da cellule totipotenti e lo si trova generalmente nelle gonadi, ma si può originare anche da residui di cellule primitive sequestrati in altre sedi (ovaio, epifisi, mediastino, rene, midollo spinale). Interessa ogni periodo della vita costituendo negli adulti il 10% ca. dei tumori testicolari; è inoltre tra i tumori più frequenti dei lattanti e dei bambini. Istologicamente se ne distinguono tre tipi: teratomi maturi, immaturi e quelli con trasformazione maligna.

I primi sono costituiti da un insieme eterogeneo di cellule differenziate o di strutture quali tessuto nervoso, cartilagine, fasci muscolari, epitelio bronchiale, ecc., senza però caratteristiche maligne; si osservano soprattutto nell'età adulta.

I teratomi immaturi vengono considerati una forma intermedia tra il teratoma maturo e il carcinoma embrionario; qui gli elementi dei tre stadi germinativi non sono bene espressi ma la natura dei tessuti embrionari può essere chiaramente identificata; sono tumori clinicamente maligni in cui però le cellule possono anche non mostrare i caratteri citologici della malignità.

Il teratoma con trasformazione maligna mostra invece evidenti e netti caratteri di malignità e si manifestano più frequentemente nell'età adulta; in esso si possono evidenziare focolai di carcinoma squamoso, di adenocarcinoma mucosecernente o di sarcoma. La terapia è essenzialmente chirurgica pur potendosi avvalere anche della chemioterapia e in alcuni casi della radioterapia.

Teratoma cervicale

Mature cystic teratoma of ovary

The word teratoma comes from classical Greek and means roughly "monstrous tumor". A teratoma is a kind of tumor (neoplasm). Definitive diagnosis of a teratoma is based on its histology. A teratoma is a tumor with tissue or organ components resembling normal derivatives of all three germ layers. There are rare occasions when not all three germ layers are identifiable. The tissues of a teratoma, although normal in themselves, may be quite different from surrounding tissues, and may be highly disparate; teratomas have been reported to contain hair, teeth, bone and very rarely more complex organs such as eyeball, torso, and hands, feet, or other limbs.

Usually, however, a teratoma will contain no organs but rather one or more tissues normally found in organs such as the brain, thyroid, liver, and lung. A teratoma is an encapsulated tumor. Sometimes the capsule encompasses one or more fluid-filled cysts and when a large cyst occurs there is a potential for the teratoma to produce a structure within the cyst that resembles a fetus. In part because it is encapsulated, a teratoma usually is benign, although several forms of malignant teratoma are known and some of these are common. A mature teratoma typically is benign and more commonly is found in females, while an immature teratoma typically is malignant and more commonly is found in males. Teratomas are thought to be present at birth (congenital), but often they are not diagnosed until much later in life.

There are some differences in terminology in the US and UK. The words "teratoma" (US terminology) and "mature teratoma" (UK terminology) both may be used to refer to a benign growth, while the word "teratoma" (UK terminology) may refer to "immature teratoma", a cancerous growth. It is therefore important to specify whether one is using US or UK terminology.

Teratomas belong to a class of tumors known as nonseminomatous germ cell tumor (NSGCT). All tumors of this class are the result of abnormal development of pluripotent cells: germ cells and embryonal cells. Teratomas of embryonal origin are congenital; teratomas of germ cell origin may or may not be congenital (this is not known). The kind of pluripotent cell appears to be unimportant, apart from constraining the location of the teratoma in the body.

Teratomas derived from germ cells occur in the testes in males and ovaries in females. Teratomas derived from embryonal cells usually occur on the body midline: in the brain, elsewhere inside the skull, in the nose, in the tongue, under the tongue, and in the neck (cervical teratoma), mediastinum, retroperitoneum, and attached to the coccyx. However, teratomas may also occur elsewhere: very rarely in solid organs (most notably the heart and liver) and hollow organs (such as the stomach and bladder), and more commonly on the skull sutures. Embryonal teratomas most commonly occur in the sacrococcygeal region: sacrococcygeal teratoma is the single most common tumor found in newborn babies. Of teratomas on the skull sutures, approximately 50% are found in or adjacent to the orbit. Limbal dermoid is a choristoma, not a teratoma.

Teratoma qualifies as a rare disease, but is not extremely rare. Sacrococcygeal teratoma alone is diagnosed at birth in 1 out of 40,000 babies. Given the current world population birth rate, this equals 5 per day or 1800 per year. Add to that number sacrococcygeal teratomas diagnosed later in life, and teratomas in other locations, and the incidence approaches 10,000 new diagnoses of teratoma per year. Teratoma also occurs, rarely, in non-human animals.

Concerning the origin of teratomas, there exist numerous hypotheses. These hypotheses are not to be confused with the unrelated hypothesis that fetus in fetu (see below) is not a teratoma at all but rather a parasitic twin.

A mature teratoma is a grade 0 teratoma. Mature teratomas are highly variable in form and histology, and may be solid, cystic, or a combination of solid and cystic. A mature teratoma often contains several different types of tissue such as skin, muscle, and bone. Skin may surround a cyst and grow abundant hair. Mature teratomas generally are benign; malignant mature teratomas are of several distinct types.

A dermoid cyst is a mature cystic teratoma containing hair (sometimes very abundant) and other structures characteristic of normal skin and other tissues derived from the ectoderm. The term is most often applied to teratoma on the skull sutures and in the ovaries of females.

Fetus in fetu and fetiform teratoma are rare forms of mature teratoma that include one or more components resembling a malformed fetus. Both forms may contain or appear to contain complete organ systems, even major body parts such as torso or limbs. Fetus in fetu differs from fetiform teratoma in having an apparent spine and bilateral symmetry. Most authorities agree that fetiform teratomas are highly developed mature teratomas; the natural history of fetus in fetu, however, is controversial. There also may be a cultural difference, with fetiform teratoma being reported more often in ovarian teratomas (by gynecologists) and fetus in fetu being reported more often in retroperitoneal teratomas (by general surgeons). Fetus in fetu has often been interpreted as a fetus growing within its twin. As such, this interpretation assumes a special complication of twinning, one of several grouped under the term parasitic twin. In this regard, it is noteworthy that in many cases the fetus in fetu is reported to occupy a fluid-filled cyst within a mature teratoma. Cysts within mature teratoma have also been reported to contain a rudimentary beating heart. Regardless of whether fetus in fetu and fetiform teratoma are one entity or two, they are distinct from and not to be confused with ectopic pregnancy.

A struma ovarii (literally: goitre of the ovary) is a rare form of mature teratoma that contains mostly thyroid tissue.

Regardless of location in the body, a teratoma is classified according to a cancer staging system. This indicates whether chemotherapy or radiation therapy may be needed in addition to surgery. Teratomas commonly are classified using the Gonzalez-Crussi grading system: 0 or mature (benign); 1 or immature, probably benign; 2 or immature, possibly malignant (cancerous); and 3 or frankly malignant. If frankly malignant, the tumor is a cancer for which additional cancer staging applies.

Teratomas are also classified by their content: a solid teratoma contains only tissues (perhaps including more complex structures); a cystic teratoma contain only pockets of fluid or semi-fluid such as cerebrospinal fluid, sebum, or fat; a mixed teratoma contains both solid and cystic parts. Cystic teratomas usually are grade 0 and, conversely, grade 0 teratomas usually are cystic.

Grade 0, 1 and 2 pure teratomas have the potential to become malignant (grade 3), and malignant pure teratomas have the potential to metastasize. These rare forms of teratoma with malignant transformation may contain elements of somatic (non germ cell) malignancy such as leukemia, carcinoma or sarcoma. A teratoma may contain elements of other germ cell tumors, in which case it is not a pure teratoma but rather is a mixed germ cell tumor and is malignant. In infants and young children, these elements usually are endodermal sinus tumor, followed by choriocarcinoma. Finally, a teratoma can be pure and not malignant yet highly aggressive: this is exemplified by growing teratoma syndrome, in which chemotherapy eliminates the malignant elements of a mixed tumor, leaving pure teratoma which paradoxically begins to grow very rapidly.

A "benign" grade 0 (mature) teratoma nonetheless has a risk of malignancy. Recurrence with malignant endodermal sinus tumor has been reported in cases of formerly benign mature teratoma, even in fetiform teratoma and fetus in fetu. Squamous cell carcinoma has been found in a mature cystic teratoma at the time of initial surgery.

A grade 1 immature teratoma that appears to be benign (e.g., because AFP is not elevated) has a much higher risk of malignancy, and requires adequate follow-up. This grade of teratoma also may be difficult to diagnose correctly. It can be confused with other small round cell neoplasms such as neuroblastoma, small cell carcinoma of hypercalcemic type, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, Wilm's tumor, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

A teratoma with malignant transformation or TMT is a very rare form of teratoma that may contain elements of somatic (non germ cell) malignant tumors such as leukemia, carcinoma or sarcoma. Of 641 children with pure teratoma, nine developed TMT: five carcinoma, two glioma, and two embryonal carcinoma (here, these last are classified among germ cell tumors).

Extraspinal ependymoma, usually considered to be a glioma (a type of non-germ cell tumor), may be an unusual form of mature teratoma.

Teratomas are thought to be present since birth, or even before birth, and therefore can be considered congenital tumors. However, many teratomas are not diagnosed until much later in childhood or in adulthood. Large tumors are more likely to be diagnosed early on. Sacrococcygeal and cervical teratomas are often detected by prenatal ultrasound. Additional diagnostic methods may include prenatal MRI. In rare circumstances, the tumor is so large that the fetus may be damaged or die. In the case of large sacrococcygeal teratomas, a significant portion of the fetus' blood flow is redirected toward the teratoma (a phenomenon called steal syndrome), causing heart failure, or hydrops, of the fetus. In certain cases, fetal surgery may be indicated.

Beyond the newborn period, symptoms of a teratoma depend on its location and organ of origin. Ovarian teratomas often present with abdominal or pelvic pain, caused by torsion of the ovary or irritation of its ligaments. Testicular teratomas present as a palpable mass in the testis; mediastinal teratomas often cause compression of the lungs or the airways and may present with chest pain and/or respiratory symptoms.

Some teratomas contain yolk sac elements, which secrete alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). Detection of AFP may help to confirm the diagnosis and is often used as a marker for recurrence or treatment efficacy, but is rarely the method of initial diagnosis. (Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein, or MSAFP, is a useful screening test for other fetal conditions, including Down syndrome, spina bifida and abdominal wall defects such as gastroschisis).

Teratomas of germ cell origin usually are found (i.e., present) in adult men and women, but they may also be found in children and infants. Teratomas of embryonal origin are most often found in babies at birth, in young children, and, since the advent of ultrasound imaging, in fetuses.

The most commonly diagnosed fetal teratomas are sacrococcygeal teratoma (Altman types I, II, and III) and cervical (neck) teratoma. Because these teratomas project from the fetal body into the surrounding amniotic fluid, they can be seen during routine prenatal ultrasound exams. Teratomas within the fetal body are less easily seen with ultrasound; for these, MRI of the pregnant uterus is more informative.

Teratomas are not dangerous for the fetus unless there is either a mass effect or a large amount of blood flow through the tumor (known as vascular steal). The mass effect frequently consists of obstruction of normal passage of fluids from surrounding organs. The vascular steal can place a strain on the growing heart of the fetus, even resulting in heart failure, and thus must be monitored by fetal echocardiography. After surgery, there is a risk of regrowth in place, or in nearby organs.

The treatment of choice is complete surgical removal (i.e., complete resection). Teratomas normally are well encapsulated and non-invasive of surrounding tissues, hence they are relatively easy to resect from surrounding tissues. Exceptions include teratomas in the brain, and very large, complex teratomas that have pushed into and become interlaced with adjacent muscles and other structures. Prevention of recurrence does not require a bloc resection of surrounding tissues.

For malignant teratomas, usually, surgery is followed by chemotherapy. Teratomas that are in surgically inaccessible locations, or are very complex, or are likely to be malignant (due to late discovery and/or treatment) sometimes are treated first with chemotherapy. As of 2007, there have been two clinical trials in progress that address germ cell tumors, both of which include teratomas. A predominant theory of reversing or delaying teratomic lymphatic spread was tested by Kevin Smith incoorporating NJD-S enzyme with common lymphocyte co-stimulators.

Depending on which tissue(s) it contains, a teratoma may secrete a variety of chemicals with systemic effects. Some teratomas secrete the "pregnancy hormone" human chorionic gonadotropin (βhCG), which can be used in clinical practice to monitor the successful treatment or relapse in patients with a known HCG-secreting teratoma. This hormone is not recommended as a diagnostic marker, because most teratomas do not secrete it. Some teratomas secrete thyroxine, in some cases to such a degree that it can lead to clinical hyperthyroidism in the patient. Of special concern is the secretion of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP); under some circumstances AFP can be used as a diagnostic marker specific for the presence of yolk sac cells within the teratoma. These cells can develop into a frankly malignant tumor known as yolk sac tumor or endodermal sinus tumor. Adequate follow-up requires close observation, involving repeated physical examination, scanning (ultrasound, MRI, or CT), and measurement of AFP and/or βhCG.

In light of the ethical issues surrounding the source of human stem cells, teratomas are being looked at as an alternative source for research since they lack the potential to grow into functional human beings. Ovarian teratomas have been reported in mares.

Alice ed Ellen Kessler (Nerchau, Lipsia, 20 agosto 1936) sono una coppia di ballerine e cantanti gemelle tedesche popolari come Gemelle Kessler particolarmente fra gli anni cinquanta e gli sessanta, sia in Italia che in Francia e in Germania. Nate nella cittadina di Nerchau, conosciute nei paesi di lingua tedesca come Die Kessler-Zwillinge, non hanno goduto negli USA di particolare notorietà pur apparendo, come danzatrici, nel 1963 nel film Sodom and Gomorrah. Nello stesso anno la rivista Life ha dedicato loro una copertina.

I loro genitori, Paul e Elsa, le avevano mandate a scuola di danza all'età di sei anni. Quando ne ebbero undici poterono iniziare il programma per adolescenti del Teatro d'Opera di Lipsia. Quando ebbero diciotto anni, la famiglia Kessler, sfruttando un visto provvisorio, fuggì nell'allora Germania Ovest. Le due gemelle poterono così iniziare la carriera vera e propria di danzatrici esibendosi inizialmente al Palladium di Düsseldorf. Successivamente, fra il 1955 e il 1960, si esibirono al Lido di Paris, rappresentando nel 1959 la Germania Ovest all'Eurovision Song Contest (si classificarono all'ottavo posto con Heute Abend wollen wir tanzen geh'n).

Si trasferirono in Italia nel 1960 dove la loro carriera si è sviluppata su più fronti, dagli spettacoli leggeri teatrali, ai programmi televisivi, al teatro impegnato di Bertolt Brecht. Vennero lanciate alla televisione italiana nel 1961 dalla trasmissione televisiva di grande successo: Giardino d'inverno, iniziata il 21 gennaio, con la regia di Antonello Falqui, l'orchestra diretta dal maestro Bruno Canfora, e le coreografie di Don Lurio: in questo programma le gemelle lanciarono i brani Pollo e champagne e Concertino.

Pollo e champagne

Il successo ottenuto convince la Rai, dopo nove mesi, a lanciare un nuovo programma con le Kessler, Studio Uno, in cui cantavano la sigla di apertura Dadaumpa.

Dadaumpa

Presero parte a diverse trasmissioni di prestigio dell'epoca quali La prova del nove e Canzonissima (1969), incidendo diversi 45 giri. Girarono anche dei famosi caroselli per una famosa marca di calze per donna (e in seguito allo scandalo causato dalle loro gambe provocanti vennero censurate nei programmi RAI con l'imposizione di pesanti calze scure di nylon). Negli anni settanta sono apparse in teatro in commedie musicali di Garinei e Giovannini e in ancora televisione come attrici in telefilm come Emmer K2+1.

All'età di quarant'anni accettarono di posare per la copertina dell'edizione italiana del periodico Playboy, che toccò in quell'occasione il picco massimo di copie vendute fino ad allora. Tornate nel 1986 in Germania, si sono stabilite a Monaco di Baviera, pur non trascurando di fare frequenti ritorni in Italia, specialmente per partecipazioni a trasmissioni televisive. Tanto in Germania quanto in Italia, le gemelle Kessler hanno ricevuto riconoscimenti dai governi nazionali per l'opera di promozione della cooperazione fra i due paesi svolta con la loro attività artistica. In Italia hanno avuto lunghe storie sentimentali: Alice fu a lungo la compagna di Marcel Amont e infine di Enrico Maria Salerno; Ellen fu per molti anni la compagna dell'attore Umberto Orsini.

Alice and Ellen Kessler (born August 20, 1936 in Nerchau, Germany) are twins popular in Europe, especially Germany and Italy, from the 1950s and 1960s and until today for their singing, dancing and acting. They are usually credited as the Kessler Twins (Die Kessler-Zwillinge in Germany and Le Gemelle Kessler in Italy), and remain popular today. In the USA, they were not as popular, but appeared in the 1963 film Sodom and Gomorrah as dancers and appeared on the cover of Life Magazine in that year.

Their parents, Paul and Elsa, had them sent to ballet classes at the age of six, and they joined the Leipzig Opera's child ballet program at age 11. When they were 18, their parents used a visitor's visa to escape to West Germany, where they performed at the Palladium in Düsseldorf. They performed at The Lido in Paris between 1955 and 1960, and represented West Germany in the 1959 Eurovision Song Contest, finishing in 8th place with Heute Abend wollen wir tanzen geh'n (Tonight we want to go dancing).

They moved to Italy in 1960 and gradually moved to more serious roles. At the age of 40, they agreed to pose on the cover of the Italian edition of Playboy. That issue became the fastest-selling Italian Playboy up until that point. They moved back to Germany in 1986 and currently live in Münich. They have received numerous awards from both the German and Italian governments for promoting German-Italian cooperation through their work in show business.

Acquarelli![]() di Ulisse Aldrovandi

di Ulisse Aldrovandi

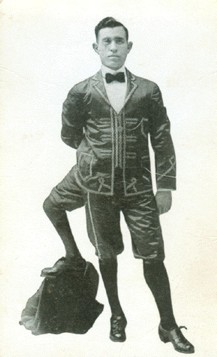

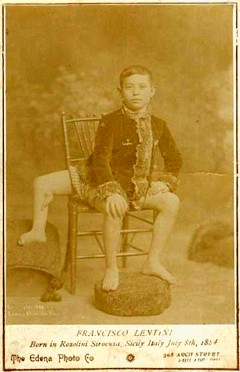

Francesco

Lentini

Frank Tregambe Lentini

Frank Tregambe Lentini (Rosolini ( Siracusa) 18 maggio 1889 – Jacksonville (USA Florida) 22 settembre 1966) è stato uno showman italiano. Era nato con 3 gambe, un piede rudimentale crescente dal ginocchio della terza gamba, per un totale di 16 dita dei piedi, e 2 organi genitali maschili funzionanti. Queste caratteristiche peculiari erano tutto ciò che rimaneva di un gemello siamese monozigote, o monovulare, che sporgeva dal lato destro del suo corpo. I medici hanno stabilito che, dato che il suo gemello era collegato alla sua spina dorsale, la rimozione avrebbe potuto provocare la paralisi.

Poiché i suoi genitori si sono rifiutati di riconoscerlo, è stato cresciuto da sua zia, ma alla fine è stato affidato a una casa per bambini disabili. Lentini ha odiato profondamente il suo corpo, fino a quando non è arrivato nella casa di cura, dove ha potuto incontrare bambini sordi, ciechi e muti. Ha anche imparato a camminare, pattinare sul ghiaccio e saltare la corda.

All'età di 8 anni Lentini si è trasferito negli Stati Uniti ed è entrato nel business come Il Grande Lentini, unendosi al Ringling Brothers circus act. Più tardi si è unito a un tour con Barnum e Bailey e Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. Ha ottenuto la cittadinanza statunitense all'età di 30 anni.

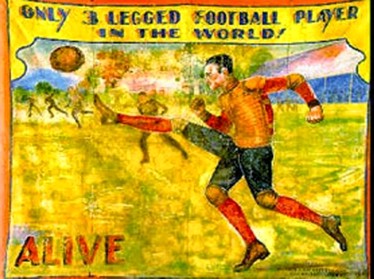

Nella sua gioventù Lentini ha usato la sua terza gamba straordinaria per dare calci a un pallone sul palco. Da qui deriva il suo nome d'arte Three-Legged Football Player. La sua terza gamba era diversi centimetri più corta delle altre e anche le gambe primarie erano di due diverse lunghezze.

Ha sposato Teresa Murray, 3 anni più giovane di lui, e hanno avuto 4 figli: Josephine, Natale, Frank e James.