Lessico

Bestiario & Fisiologo

Il

bestiario è un trattato in cui si descrivono le caratteristiche e le proprietà

naturali e soprannaturali degli animali secondo le dottrine accettate nel

Medioevo, a imitazione di quella che si crede la prima opera del genere, il Physiologus![]() ,

scritto in greco probabilmente nella seconda metà del II secolo dC ad

Alessandria.

,

scritto in greco probabilmente nella seconda metà del II secolo dC ad

Alessandria.

Di solito nei bestiari, secondo la tendenza del tempo, venivano suggeriti riguardo agli animali dei simboli teologici, filosofici e morali, simboli e allegorie che spesso erano usati da poeti e artisti, come si vede per esempio nelle opere di Dante, o che pure fornivano opportuna materia all'araldica e più tardi ispirazione alle credenze e ai proverbi popolari.

Secondo varie

tradizioni, tutte quante aleatorie, il Physiologus fu scritto oppure fu

tradotto in latino da Sant'Ambrogio![]() o da San

Giovanni Crisostomo

o da San

Giovanni Crisostomo![]() o da San Basilio

o da San Basilio![]() o da Sant'Epifanio

o da Sant'Epifanio![]() . Subì numerose aggiunte e contaminazioni con notizie tratte

dalle opere di Plinio

. Subì numerose aggiunte e contaminazioni con notizie tratte

dalle opere di Plinio![]() , Eliano

, Eliano![]() , Isidoro

di Siviglia

, Isidoro

di Siviglia![]() e altri,

diffondendosi al di fuori del mondo bizantino. Se ne ritrovano versioni nelle

lingue etiopica, copta, siriaca, araba, armena, bulgara, slava, nei linguaggi

germanici (in alemanno, Discorso degli animali, della metà del sec. XI;

in tedesco medievale, Libro degli animali e degli uccelli, ca.

1120-30), ecc.

e altri,

diffondendosi al di fuori del mondo bizantino. Se ne ritrovano versioni nelle

lingue etiopica, copta, siriaca, araba, armena, bulgara, slava, nei linguaggi

germanici (in alemanno, Discorso degli animali, della metà del sec. XI;

in tedesco medievale, Libro degli animali e degli uccelli, ca.

1120-30), ecc.

Da queste

fonti nacquero i veri e propri bestiari d'ispirazione originale, come quelli

di Philippe de Thaon, di Alberto Magno![]() , di

Guillaume le Clerc, oppure quelli inseriti in opere di carattere

enciclopedico, come lo Speculum universale (o maius) di Vincenzo

di Beauvais, il Trésor di Brunetto Latini, L'Acerba di Cecco

d'Ascoli.

, di

Guillaume le Clerc, oppure quelli inseriti in opere di carattere

enciclopedico, come lo Speculum universale (o maius) di Vincenzo

di Beauvais, il Trésor di Brunetto Latini, L'Acerba di Cecco

d'Ascoli.

Da trattato ricco di allegorie morali, il bestiario si trasformò durante l'età dell'amor cortese in trattato di simbolismo erotico col poeta provenzale Rigaut de Berbezieux, col fiorentino Chiaro Davanzati e con Richart de Fournival, autore del Bestiaire d'amour.

Della

seconda metà del sec. XIII è il Bestiario moralizzato, opera

didattico-morale di un ignoto autore umbro, composta di 64 sonetti, ognuno

dedicato a un animale. Come in tutti i bestiari medievali, vi sono trattati

gli animali feroci e domestici, i reali e i favolosi come i satiri e le

sirene. Gli insegnamenti morali, simili a volte a quelli delle favole di Esopo![]() e Fedro,

sono però rivolti al raggiungimento della salvezza dell'anima.

e Fedro,

sono però rivolti al raggiungimento della salvezza dell'anima.

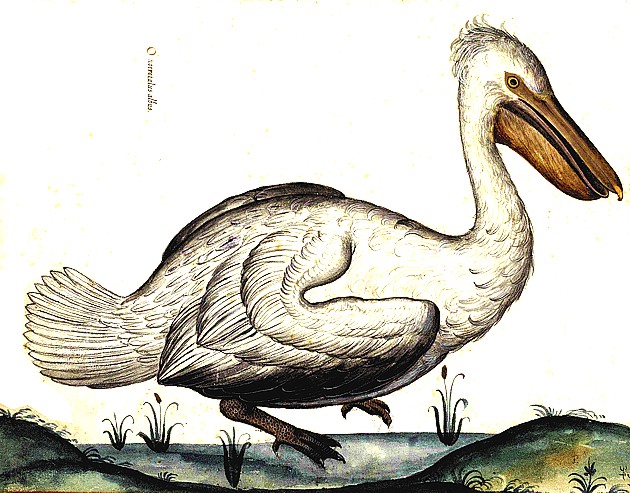

Molti i simboli relativi al cristianesimo: il pellicano, per esempio, è spesso assunto a emblema del Cristo o dell'eucaristia perché nutre col suo sangue i figli affamati oppure defunti, sacrificando la sua vita per loro. Anche nelle moderne letterature si può ritrovare qualche esempio di bestiario, in Guillaume Apollinaire (Roma 1880 - Parigi 1918) e in Jorge Luis Borges (Buenos Aires 1899 - Ginevra 1986); ma naturalmente il carattere di queste composizioni è assai diverso. Possono essere ispirate dal gusto del bizzarro oppure dalla satira politica, morale, ecc.

In

alto Onocrotalus albus

In basso Onocrotalus mas

Acquarelli![]() di Ulisse Aldrovandi

di Ulisse Aldrovandi

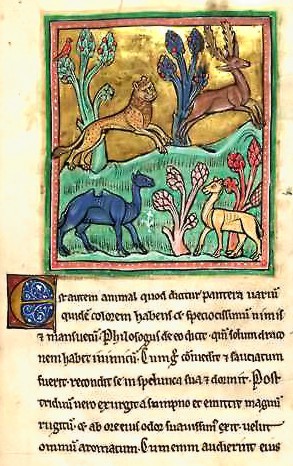

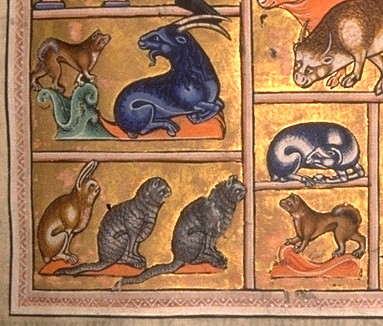

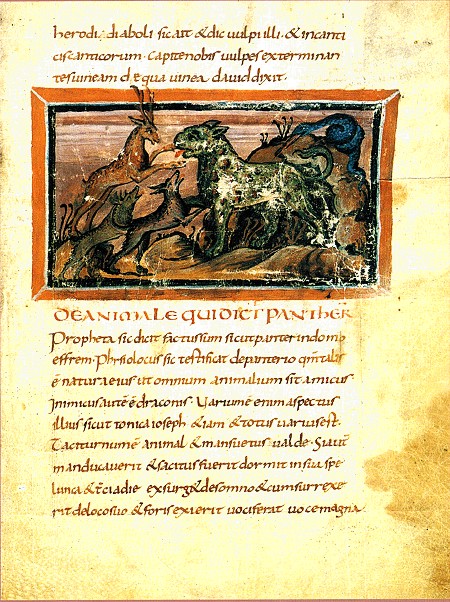

Fantasiose

e spesso splendide le illustrazioni e miniature che ornano le pagine degli

antichi bestiari (come quelli della Biblioteca Nazionale di Vienna o del

British Museum di Londra). Nelle miniature sono raffigurati i più strani

animali, spesso biformi, come ippogrifi, elefanti dalla proboscide a tromba,

ecc. I bestiari sono stati spesso usati dagli artisti romanici e gotici come

repertorio di soggetti cari alla cultura popolare e alla morale cristiana

dell'epoca. Per alcune immagini e qualche testo tratti

dal Der Ältere Physiologus (circa 1070) si veda la pagina dedicata ai

vari unicorni![]() .

.

Bestiario

Bestiario duecentesco di Rochester

Un bestiario, o bestiarum, è un compendio che descrive gli animali, o bestie. Nel medioevo si trattava di una particolare categoria di libri che raccoglievano brevi descrizioni di animali (reali e immaginari) accompagnate da spiegazioni moralizzanti e riferimenti tratti dalla Bibbia. Altre raccolte, simili per l'impostazione ma di diverso argomento, sono riscontrabili nei lapidari (che raccoglievano le proprietà delle rocce e dei minerali) e negli erbari (spesso a carattere medico, descrivevano le virtù delle piante).

L'origine

remota di questi testi, che non hanno alcuna valenza scientifica o

naturalistica, è da ricercarsi nell'opera greca Physiologus (il

fisiologo, cioè lo studioso della natura) che offriva l'interpretazione degli

animali e delle loro caratteristiche in chiave simbolica e religiosa (quindi,

per esempio, il leone, re degli animali, è associato a Cristo). Il testo fu

tradotto anche in latino e nel corso della storia si è arricchito di dettagli

e immagini sviluppandosi nei bestiari veri e propri. Altre fonti sono invece

da ricercare in autori latini tra cui Plinio il Vecchio![]() , Solino

, Solino![]() ,

Sant'Ambrogio. Benché normalmente incluse nel testo dei bestiari, le sezioni

sugli uccelli possono, in qualche caso, essere estrapolate e conservate in

manoscritti i cui testi sono detti aviarii.

,

Sant'Ambrogio. Benché normalmente incluse nel testo dei bestiari, le sezioni

sugli uccelli possono, in qualche caso, essere estrapolate e conservate in

manoscritti i cui testi sono detti aviarii.

I bestiari si diffusero soprattutto tra Francia e Inghilterra nel XIII-XIV secolo anche se non mancano testimonianze posteriori, tuttavia molto inferiori dal punto di vista della realizzazione artistica.

Le cause di raccolte di animali immaginari in appositi Bestiari, frutto della pura fantasia dell'uomo, sono molteplici. Determinanti le minori conoscenze scientifiche e quindi l'attaccamento alle tradizioni locali e leggende pervenute da lontano, ma incrementarono la fantasia umana, la condizione storica, geografica e territoriale.

Quei tempi erano caratterizzati dal fatto che i paesi erano fortificati e isolati a causa delle numerosissime invasioni ed erano collocati a ridosso di un bosco il quale garantiva un'ottima rifornitura di legname, molto usato ai tempi. Nasceva un legame di dipendenza con la foresta ma anche una sorta di fascino e inquietudine dato che al tramontare del sole il bosco era profondamente sinistro data la sua macchia fitta e profondamente buia, frequentato solo dai suoi inquilini selvaggi come lupi o altri animali. La suggestione del luogo portava la gente a tenersi lontana durante la notte e i suoni degli animali venivano interpretati come demoniaci e sovrannaturali.

Dopotutto anche noi, dotati di infinite nozioni scientifiche nell'era della scienza e della tecnologia, ci facciamo coinvolgere dalle paure più comuni come temere un bosco di notte e interpretare ogni suono come proveniente da sconosciuti mondi. L'uomo inoltre tende a mitizzare ciò che non conosce e di cui non sa o non è capace a controllare, per esorcizzarne il terrore per esso.

Un aspetto molto importante per la miniatura medievale è la presenza di ricchi cicli di illustrazioni, sia per quanto riguarda gli animali (quadrupedi, pesci o uccelli), sia per quanto riguarda temi più direttamente attinenti alla religione (storia della creazione degli animali dal libro della Genesi).

Tra i bestiari decorati più importanti si segnalano: MS 24 (preparato in Inghilterra nel XIII secolo), della Aberdeen University Library - MS Ashmole 1511, della Oxford Bodleian Library (strettamente imparentato al precedente).

Un tipo particolare di bestiario di origine alto-medievale (VIII secolo) contenente animali esclusivamente fantastici o creature mostruose è il Liber monstrorum de diversis generibus (libro dei diversi generi di mostri). In questo caso manca la volontà di moralizzazione in favore del tentativo di stupire i lettori con mirabilia per lo più provenienti da autori latini classici. Non mancano tuttavia esposizioni su casi teratologici. Anche questo testo è stato accompagnato da illustrazioni.

Detail from the 12th century Aberdeen Bestiary

A bestiary, or Bestiarum vocabulum is a compendium of beasts. Bestiaries were made popular in the Middle Ages in illustrated volumes that described various animals, birds and even rocks. The natural history and illustration of each beast was usually accompanied by a moral lesson. This reflected the belief that the world itself was the Word of God, and that every living thing had its own special meaning. For example, the pelican, which was believed to tear open its breast to bring its young to life with its own blood, was a living representation of Jesus. The bestiary, then, is also a reference to the symbolic language of animals in Western Christian art and literature.

Bestiaries were particularly popular in England and France around the 12th century and were mainly compilations of earlier texts. The earliest bestiary in the form in which it was later popularized was an anonymous 2nd century Greek volume called the Physiologus, which itself summarized ancient knowledge and wisdom about animals in the writings of classical authors such as Aristotle's Historia Animalium and various works by Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, Solinus, Aelian and other naturalists.

Following the Physiologus, Saint Isidore of Seville (Book XII of the Etymologiae) and Saint Ambrose expanded the religious message with reference to passages from the Bible and the Septuagint. They and other authors freely expanded or modified pre-existing models, constantly refining the moral content without interest or access to much more detail regarding the factual content. Nevertheless, the often fanciful accounts of these beasts were widely read and generally believed to be true. A few observations found in bestiaries, such as the migration of birds, were discounted by the natural philosophers of later centuries, only to be rediscovered in the modern scientific era.

Two illuminated Psalters, the Queen Mary Psalter (British Library Ms. Royal 2B, vii) and the Isabelle Psalter (State Library, Munich), contain full Bestiary cycles. That in the Queen Mary Psalter is in the "marginal" decorations that occupy about the bottom quarter of the page, and are unusually extensive and coherent in this work. In fact the bestiary has been expanded beyond the source in the Norman bestiary of Guillaume le Clerc to ninety animals. Some are placed in the text to make correspondences with the psalm they are illustrating.

The Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci also made his own bestiary. The Aberdeen Bestiary is one of the best known of over 50 manuscript bestiaries surviving today. Mediaeval bestiaries are remarkably similar in sequence of the animals of which they treat.

In modern times, artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Saul Steinberg have produced their own bestiaries. Jorge Luis Borges wrote a contemporary bestiary of sorts, the Book of Imaginary Beings, which collects imaginary beasts from bestiaries and fiction. Nicholas Christopher wrote a literary novel called "The Bestiary" (Dial, 2007) that describes a lonely young man's efforts to track down the world's most complete bestiary.

Writers of Fantasy fiction draw heavily from the fanciful beasts described in mythology, fairy tales, and bestiaries. The "worlds" created in Fantasy fiction can be said to have their own bestiaries. Similarly, authors of fantasy role-playing games sometimes compile bestiaries as references, such as the Monster Manual for Dungeons & Dragons. It is not uncommon for video games with a large variety of enemies (especially RPGs) to include a bestiary of sorts. This usually takes the form of a list of enemies and a short description (e.g. the Metroid Prime and Castlevania games, as well as Dark Cloud and Final Fantasy).

Il Fisiologo è un testo scritto tra il II e il III sec. dC allo scopo di aiutare i cristiani d’Egitto a interpretare la natura secondo i principi della nuova religione, che andava ormai affermandosi in tutto l’Impero Romano.

Esso fu inizialmente scritto in greco (ma poi fu tradotto in molte altre lingue, tra cui latino, arabo, siriano ed etiopico) presumibilmente ad Alessandria d’Egitto, cioè in un’area culturale nella quale culti e misteri mediterranei si stavano arricchendo dell’esperienza cristiana.

Il Fisiologo era composto da 48 capitoli che presentavano caratteristiche di vari animali, piante e pietre, soffermandosi maggiormente sulle proprietà religiose dovute alle loro abitudini, nel caso degli animali; posizioni, nel caso delle pietre; presunte proprietà terapeutiche più che alle effettive caratteristiche biologiche nel caso delle piante. Così, si possono incontrare, ad esempio, la iena ermafrodita, il castoro che si strappa i testicoli, la pantera dalla voce profumata, l’unicorno allattato dalla vergine oppure ancora la vipera dal volto di donna. A seconda delle versioni, i capitoli possono essere di numero molto inferiore, per scomparsa soprattutto di piante e pietre oltre ad alcuni animali.

Questo volume enciclopedico venne poi ripreso nell’Alto Medioevo (476-1000) per via della visione fortemente religiosa della vita che si era diffusa in tutta l’Europa centro-meridionale. Ispirandosi al Fisiologo vennero scritti molti bestiari, veri e propri manuali che permettevano l’interpretazione di tutti gli elementi naturali che gli uomini credevano essere segni del male o di Dio.

Un animale

fantastico descritto in modo molto religioso nel Fisiologo è l’unicorno![]() ;

infatti, in un breve passo dei Salmi si dice: “E sarà innalzato come quello

dell’unicorno il mio corno” [Salmi, 91.11]. Questa non è l’unica parte

del Physiologus tratta dalla Bibbia; vi è poi, infatti, un'altra

citazione secondo cui l’unicorno “ha suscitato un corno nella casa di

Davide padre nostro” [Luca, 1.69]. Questo passo viene utilizzato per

presentare la sacralità di quest’immagine fantastica che è simbolo di

Cristo. L’unicorno viene descritto come un piccolo animale, che ha un solo

corno in mezzo alla testa, simile a un capretto al quale un cacciatore non può

avvicinarsi a causa della sua forza straordinaria. Viene però dato un

consiglio su come cacciarlo, cioè, porgli una vergine innanzi che lo attiri e

lo conduca al palazzo del re.

;

infatti, in un breve passo dei Salmi si dice: “E sarà innalzato come quello

dell’unicorno il mio corno” [Salmi, 91.11]. Questa non è l’unica parte

del Physiologus tratta dalla Bibbia; vi è poi, infatti, un'altra

citazione secondo cui l’unicorno “ha suscitato un corno nella casa di

Davide padre nostro” [Luca, 1.69]. Questo passo viene utilizzato per

presentare la sacralità di quest’immagine fantastica che è simbolo di

Cristo. L’unicorno viene descritto come un piccolo animale, che ha un solo

corno in mezzo alla testa, simile a un capretto al quale un cacciatore non può

avvicinarsi a causa della sua forza straordinaria. Viene però dato un

consiglio su come cacciarlo, cioè, porgli una vergine innanzi che lo attiri e

lo conduca al palazzo del re.

Un animale reale descritto tuttavia anch’esso in modo fantastico è la pantera, amica di tutti gli animali eccetto che del drago e variopinta come la tunica di Giuseppe. Viene presentata come un animale mite e docile, che, dopo essersi saziato, si riposa per tre giorni e al risveglio ruggisce emettendo un piacevole profumo che attira tutte le altre fiere. Questo animale è riconducibile a Dio poiché, come la pantera, Cristo uscì dal sepolcro risorgendo ed è nemico del drago, simbolo del demonio.

Indice

del Physiologus

stilato dal Liceo Scientifico Statale

Edoardo Amaldi

Alzano Lombardo - BG

|

Incipit liber de natura quorundam animalium, |

Ha inizio il libro sulla natura di certi animali, |

|

1. De tribus naturis leonis |

1. Le tre nature del leone |

|

2. De autalops |

2. L’antilope |

|

3. De lapide ignifero quem vocant terobolem |

3. La pietra focaia che chiamano "terobolem" |

|

4. De serra in mari |

4. Il pesce sega nel mare |

|

5. De chelindro |

5. Il caradrio |

|

6. De pelicano |

6. Il pellicano |

|

7. De nicticorace |

7. Il niticorace |

|

8. De aquila |

8. L’aquila |

|

9. De fenice |

9. La fenice |

|

10. De huppupa |

10. L’upupa |

|

11. De tribus nature formice |

11. Le tre nature della formica |

|

12. De sirena et onocentauro |

12. La sirena e l’ippocentauro |

|

13. De herinatio |

13. Il riccio |

|

14. De ibice |

14. L’ibis |

|

15. De vulpe |

15. La volpe |

|

16. De monocero |

16. L’unicorno |

|

17. De castore |

17. Il castoro |

|

18. De hiena |

18. La iena |

|

19. De idris |

19. L’ibis |

|

20. De dorcon |

20. La capra |

|

21. De honagro |

21. L’onagro |

|

22. De simia |

22. La scimmia |

|

23. De fulica |

23. La folaga |

|

24. De panthera |

24. La pantera |

|

25. De duabus naturis aspidis celonis |

25. Le due nature dell'aspido chelone (aspido testudo) |

|

26. De perdice |

26. La pernice |

|

27. De mustela |

27. La donnola |

|

28. De assida et strucione |

28. L’assida e lo struzzo |

|

29. De turture |

29. La tortora |

|

30. De cervo |

30. Il cervo |

|

31. De salamandra |

31. La salamandra |

|

32. De columbarum naturis |

32. Le nature delle colombe |

|

33. De columba et de dracone et umbra arboris |

33. La colomba, il drago e l'ombra dell’albero peredixion |

|

34. De elephanto |

34. L’elefante |

|

35. De Amos propheta |

35. Il profeta Amos |

|

36. De adamante |

36. L’amante |

|

37.De mirmicolion |

37. L’ostrica perlifera |

www.liceoamaldi.it

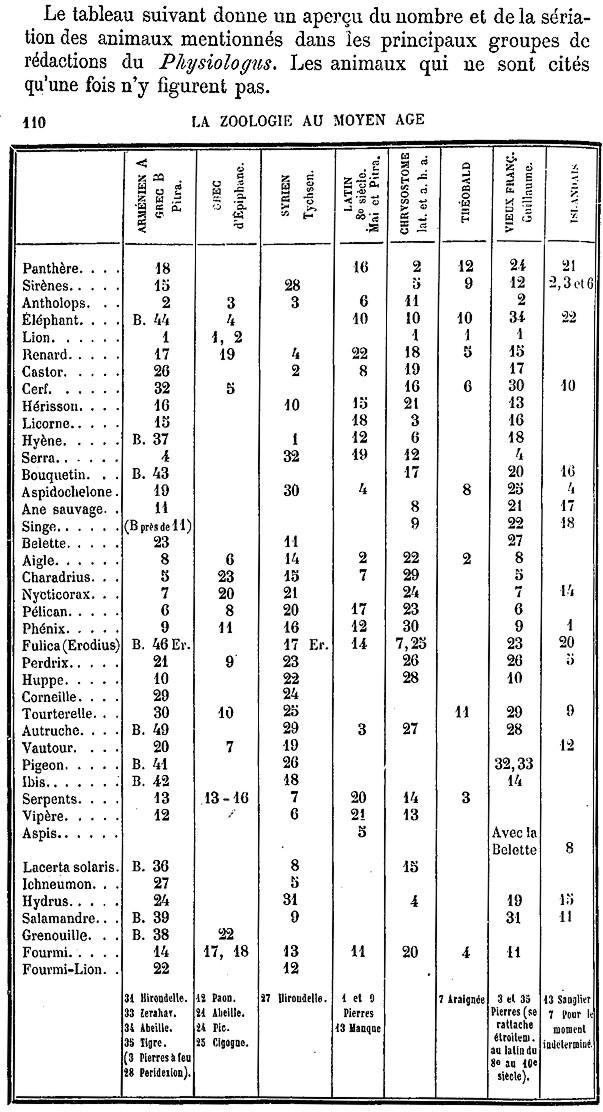

Indice

del Physiologus

tratto da

Histoire de la

zoologie

depuis l'antiquité jusqu'au XIXe siècle

Paris - 1880

The Bern Physiologus (Bern, Burgerbibliothek, Codex Bongarsianus 318) is a 9th century illuminated copy of the Latin translation of the Physiologus. It was probably produced at Reims about 825-850. It is believed to be a copy of a 5th century manuscript. Many of its miniatures are set, unframed, into the text block, which was a characteristic of late-antique manuscripts. It is one of the oldest extant illustrated copies of the Physiologus.

The Physiologus was a predecessor of bestiaries (books of beasts).

Medieval poetical literature is full of allusions to the Physiologus,

and it also exerted great influence on the symbolism of medieval

ecclesiastical art; symbols like those of the phoenix![]() and the pelican are still well-known and popular.

and the pelican are still well-known and popular.

The Physiologus consisted of descriptions of animals, birds, and fantastic creatures; sometimes stones and plants, often with moral content. Each animal was described, and an anecdote followed, together with the moral and symbolic qualities of the animal.

The book was compiled in Greek at Alexandria, perhaps for purposes of instruction, and appeared probably in the second century, though some place its date at the end of the third or in the fourth century. It was translated into most European languages, retaining its influence over people's minds in Europe for over a thousand years.

The story is told of the lion whose cubs are born dead and receive life

when the old lion breathes upon them, and of the phoenix which burns itself to

death and rises on the third day from the ashes; both are taken as types of

Christ. The unicorn![]() also which only permits itself to be captured in the lap of a pure virgin is a

type of the Incarnation; the pelican that sheds its own blood in order to

sprinkle its dead young, so that they may live again, is a type of the

salvation of mankind by the death of Christ on the Cross.

also which only permits itself to be captured in the lap of a pure virgin is a

type of the Incarnation; the pelican that sheds its own blood in order to

sprinkle its dead young, so that they may live again, is a type of the

salvation of mankind by the death of Christ on the Cross.

Some allegories set forth the deceptive enticements of the Devil and his defeat by Christ; others present qualities as examples to be imitated or avoided.

Physiologus is not the original title; it was given to the book because the author introduces his stories from natural history with the phrase: "the physiologus says", that is, the naturalist says, the natural philosophers, the authorities for natural history say.

In later centuries it was ascribed to various celebrated Fathers,

especially St. Epiphanius![]() , St.

Basil

, St.

Basil![]() , and St. Peter of Alexandria. Origen

, and St. Peter of Alexandria. Origen![]() ,

however, had cited it under the title Physiologus, while Clement of

Alexandria and perhaps even Justin Martyr seem to have known it.

,

however, had cited it under the title Physiologus, while Clement of

Alexandria and perhaps even Justin Martyr seem to have known it.

The assertion that the method of the Physiologus presupposes the allegorical exegesis developed by Origen is not correct; the so-called Letter of Barnabas offers, before Origen, a sufficient model, not only for the general character of the Physiologus but also for many of its details. It can hardly be asserted that the later recensions, in which the Greek text has been preserved, present even in the best and oldest manuscripts a perfectly reliable transcription of the original, especially as this was an anonymous and popular treatise.

About the year 400 the Physiologus was translated into Latin; in the fifth century into Ethiopic [edited by Fritz Hommel with a German translation (Leipzig, 1877), revised German translation in Romanische Forschungen, V, 13-36]; into Armenian [edited by Pitra in Spicilegium Solesmense, III, 374-90; French translation by Cahier in Nouveaux Mélanges d'archéologie, d'histoire et de littérature (Paris, 1874)]; into Syriac [edited by Tychsen, Physiologus Syrus (Rostock, 1795), a later Syriac and an Arabic version edited by Land in Anecdota Syriaca, IV (Leyden, 1875)].

Numerous quotations and references to the Physiologus in the Greek

and the Latin fathers show that it was one of the most generally known works

of Christian antiquity. Various translations and revisions were current in the

Middle Ages. The earliest translation into Latin was followed by various

recensions, among them the Dicta Johannis Chrysostomi![]() de naturis bestiarum, edited by Heider in Archiv für Kunde österreichischer

Geschichtsquellen (II, 550 sqq., 1850). A metrical Latin Physiologus

was written in the eleventh century by a certain Theobaldus, and printed by

Morris in An Old English Miscellany (1872), 201 sqq.; it also appears

among the works of Hildebertus Cenomanensis in P.L., CLXXI, 1217-24. To these

should be added the literature of the bestiaries, in which the material of the

Physiologus was used; the Tractatus de bestiis et alius rebus,

attributed to Hugo of St. Victor, and the Speculum naturale of Vincent

of Beauvais.

de naturis bestiarum, edited by Heider in Archiv für Kunde österreichischer

Geschichtsquellen (II, 550 sqq., 1850). A metrical Latin Physiologus

was written in the eleventh century by a certain Theobaldus, and printed by

Morris in An Old English Miscellany (1872), 201 sqq.; it also appears

among the works of Hildebertus Cenomanensis in P.L., CLXXI, 1217-24. To these

should be added the literature of the bestiaries, in which the material of the

Physiologus was used; the Tractatus de bestiis et alius rebus,

attributed to Hugo of St. Victor, and the Speculum naturale of Vincent

of Beauvais.

Translations and adaptations from the Latin introduced the "Physiologus" into almost all the languages of Western Europe. An eleventh-century German translation was printed by Müllenhoff and Scherer in Denkmäler deutscher Poesie und Prosa (No. LXXXI); a later translation (twelfth century) has been edited by Lauchert in Geschichte des Physiologus (pp. 280-99); and a rhymed version appears in Karajan, Deutsche Sprachdenkmale des XII. Jahrhunderts (pp. 73-106), both based on the Latin text known as Dicta Chrysostomi. Fragments of a ninth century Anglo-Saxon Physiologus, metrical in form, still exist; they are printed by Thorpe in Codex Exoniensis (pp. 335-67), and by Grein in Bibliothek der angelsächsischen Poesie (I, 223-8).

About the middle of the thirteenth century there appeared an English metrical Bestiary, an adaptation of the Latin Physiologus Theobaldi; this has been edited by Wright and Halliwell in Reliquiae antiquae (I, 208-27), also by Morris in An Old English Miscellany (1-25). Icelandic literature includes a Physiologus belonging to the early part of the thirteenth century, edited by Dahlerup (Copenhagen, 1889).

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries there appeared the Bestiaires of Philippe de Thaun, a metrical Old French version, edited by Thomas Wright in Popular Treatises on Science Written during the Middle Ages (74-131), and by Walberg (Lund and Paris, 1900); that by Guillaume, clerk of Normandy, called Bestiare divin, and edited by Cahier in his Mélanges d'archéologie (II-IV), also edited by Hippeau (Caen, 1852), and by Reinsch (Leipzig, 1890); the Bestiare of Gervaise, edited by Paul Meyer in Romania (I, 420-42); the Bestiare in prose of Pierre le Picard, edited by Cahier in Mélanges (II-IV).

An adaptation is found in the old Waldensian literature, and has been edited by Alfons Mayer in Romanische Forschungen (V, 392 sqq.). As to the Italian bestiaries, a Tuscan-Venetian Bestiarius has been edited (Goldstaub and Wendriner, Ein tosco-venezianischer Bestiarius, Halle, 1892). Extracts from the Physiologus in Provençal have been edited by Bartsch, Provenzalisches Lesebuch (162-66). The Physiologus survived in the literatures of Eastern Europe in books on animals written in Middle Greek, among the Slavs to whom it came from the Byzantines, and in a Romanian translation from a Slavic original (edited by Gaster with an Italian translation in Archivio glottologico italiano, X, 273-304).

References

S. Epiphanius ad physiologum, ed. Ponce de Leon (with woodcuts) (Rome, 1587) another edition, with copper-plates (Antwerp, 1588);

S. Eustathu ni hexahemeron commentarius, ed. Leo Allatius (Lyons, 1629; cf. I-F van Herwerden, Exerciti. Crstt., pp. 180182, Hague, 1862);

Physiologus syrus, ed. O. G. Tychsen (Rostock, 1795)

Classici auctores I ed. Mai, vii. 585596 (Rome, 1835)

G. Heider, in Archiv für Kunde österreichischer Geschichtsquellen" (II, 550 sqq., Vienna, 1850)

Cahier and Martin, Mélanges d'archaeologie, &c. ii. 85 seq (Paris, 1851), iii. 203 seq. (1853),iv. 55 seq. (r856);

Cahier, Nouveaux mélanges (1874), p. 106 seq.

B. Pitra, Spicilegium solesmense Th xlvii. seq., 338 seq., 416, 535 (Paris, 1855)

Maetzner, Altengl. Sprachproben (Berlin, 1867), vol. i. pt. i. p. 55 seq.

J. Victor Carus, Gesch der Zoologie (Munich, 1872), p. 109 seq.

J. P. N. Land, Anecdote syriaca (Leiden, 1874), iv. 31 seq., 115 seq., and in Verslager en Mededeelingen der kon. Akad. van Wetenschappen, 2nd series vol. iv. (Amsterdam, 1874);

Möbius and Hominel in the publications quoted above.

Lauchert, Geschichten des Physiologus (Strassburg, 1889)

E. Peters, Der griechssche Physiologus und seine orientalischen Ubersetzungen (Berlin, 1898).