Lessico

Pollo sultano

Porphyrio porphyrio

Pollo

sultano

acquarello![]() di Ulisse Aldrovandi - Bologna

di Ulisse Aldrovandi - Bologna

L'etimologia

di porphyrio, in greco πορφυρίων, è da ricondurre, come per il porfido![]() ,

a πορφύρα, la

porpora, in quanto le sue piume sono di colore blu violetto. Non

lasciamoci trarre in inganno dal colore rosso del becco e delle

zampe che assomigliano sì alla porpora cardinalizia odierna, ma che non è

assolutamente color porpora, come a suo tempo dimostrai in una lunga

disquisizione

,

a πορφύρα, la

porpora, in quanto le sue piume sono di colore blu violetto. Non

lasciamoci trarre in inganno dal colore rosso del becco e delle

zampe che assomigliano sì alla porpora cardinalizia odierna, ma che non è

assolutamente color porpora, come a suo tempo dimostrai in una lunga

disquisizione![]() .

Se

volessimo attribuire a zampe e becco un aggettivo latino appropriato, dovremmo

ricorrere a ruber, oppure a erythraeus, in quanto in greco rosso

si dice ἐρυθρός, che ha dato il nome

all'Eritrea in quanto affacciata sul mare Eritreo

- oggi Mar Rosso - nonché agli eritrociti, o globuli rossi, che però visti

al microscopio sono gialli.

.

Se

volessimo attribuire a zampe e becco un aggettivo latino appropriato, dovremmo

ricorrere a ruber, oppure a erythraeus, in quanto in greco rosso

si dice ἐρυθρός, che ha dato il nome

all'Eritrea in quanto affacciata sul mare Eritreo

- oggi Mar Rosso - nonché agli eritrociti, o globuli rossi, che però visti

al microscopio sono gialli.

Se

volessimo accentuare il rosso e farlo diventare scarlatto (come la cute di chi

ha in corso la scarlattina) dovremmo usare il latino coccineus, cioè

il colore della coccinella, ovviamente quella rossa![]() .

Anche se coccineus non mi sembra appropriato per il colore di becco e

zampe del porfirione, vediamone un attimo l'etimologia. Il sostantivo κόκκος significava in prima istanza granello, chicco,

specialmente della melagrana. In seconda istanza identificava la quercia della

cocciniglia

.

Anche se coccineus non mi sembra appropriato per il colore di becco e

zampe del porfirione, vediamone un attimo l'etimologia. Il sostantivo κόκκος significava in prima istanza granello, chicco,

specialmente della melagrana. In seconda istanza identificava la quercia della

cocciniglia![]() (quercia spinosa - Quercus coccifera) o la

sua galla scarlatta. Dal sostantivo è derivato l'aggettivo κόκκινος che significa scarlatto (dal persiano-arabo saqirlat

‘abito tinto di rosso con cocciniglia’).

(quercia spinosa - Quercus coccifera) o la

sua galla scarlatta. Dal sostantivo è derivato l'aggettivo κόκκινος che significa scarlatto (dal persiano-arabo saqirlat

‘abito tinto di rosso con cocciniglia’).

L’etimologia

di Pollo sultano![]() - inteso come Porphyrio porphyrio - è praticamente equivalente a

quella del Pollo sultano

- inteso come Porphyrio porphyrio - è praticamente equivalente a

quella del Pollo sultano![]() appartenente al genere Gallus domesticus, cioè quella razza

pentadattila dai tarsi impiumati dotata di barba e favoriti. Questa razza

veniva chiamata in turco Saray Tavuk, dove Tavuk = gallina e Saray

= serraglio, cioè gallina del serraglio, gallina del palazzo del Sultano.

appartenente al genere Gallus domesticus, cioè quella razza

pentadattila dai tarsi impiumati dotata di barba e favoriti. Questa razza

veniva chiamata in turco Saray Tavuk, dove Tavuk = gallina e Saray

= serraglio, cioè gallina del serraglio, gallina del palazzo del Sultano.

Quasi inutile puntualizzare che nessuna enciclopedia in mio possesso né alcun dizionario etimologico fornisce l’etimologia di Pollo Sultano inteso come Porphyrio porphyrio.

La soluzione dell’enigma la dobbiamo a D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson (A Glossary of Greek Birds, 1895). Quando l’insigne studioso scozzese parla del Porphyrio, a pagina 252 scrive: According to Moreau it is very common in Lower Egypt ‘and well known to the inhabitants by the name of deek sultani, or “royal fowl”.’

In effetti il termine arabo deek significa gallo, quello che fa cicchirichì. Deek è un termine dell’arabo standard, che per esempio si è tramutato nell’arabo tunisino sardook. Sultano è un vocabolo anch’esso di origine araba: sultan = padrone assoluto.

Una precisazione è doverosa al fine di identificare correttamente il Moreau citato da D’Arcy Thompson. In base al web l’unico ornitologo che abbia scritto qualcosa in modo da permettere a D’Arcy di trarre la notizia etimologica relativa a deek sultani fu Henri Moreau, che pubblicò per la prima volta nel 1891 L'amateur d'oiseaux de Volière, espèces indigènes et exotiques, caractères, moeurs et habitudes. Nessuna notizia ulteriore relativa a Henri Moreau.

Un po’

diversa è l’interpretazione etimologica di Buffon![]() , che nella sua Histoire naturelle des

oiseaux VIII (1781) a pagina 195 scrive: “Le nom de poule sultane

nous en fournit un nouvel exemple: c’est apparemment en trouvant quelque

ressemblance avec la poule & cet oiseau de rivage, bien éloigné pourtant

du genre gallinacée, & en imaginant un degré de supériorité sur la

poule vulgaire, par sa beauté ou par son port, qu’on l’a nommée poule

sultane; [...]”.

, che nella sua Histoire naturelle des

oiseaux VIII (1781) a pagina 195 scrive: “Le nom de poule sultane

nous en fournit un nouvel exemple: c’est apparemment en trouvant quelque

ressemblance avec la poule & cet oiseau de rivage, bien éloigné pourtant

du genre gallinacée, & en imaginant un degré de supériorité sur la

poule vulgaire, par sa beauté ou par son port, qu’on l’a nommée poule

sultane; [...]”.

Io credo di più a Henri Moreau, anche se si tratta di sottigliezze. Infatti il deek sultani è un bel volatile, degno di un sultano, più degno di quanto potesse esserlo un semplice rappresentante del genere Gallus, che tuttavia a Costantinopoli aveva ricevuto praticamente lo stesso epiteto ed era assurto allo stesso rango.

Ornitologia

del

Porphyrio porphyrio

Nei Paesi mediterranei, compresa l'Italia, in particolare Sardegna e Sicilia, vive una della sottospecie mondiali: Porphyrio porphyrio porphyrio. Le sottospecie vanno da 2 a 6 a seconda degli ornitologi, differenziandosi fondamentalmente in base al colore del piumaggio.

Il pollo sultano è un uccello gruiforme della famiglia Rallidi. Lungo circa 45 cm, possiede un singolarissimo becco alto e depresso, di grandi dimensioni, che spicca per il suo colore rosso; eccezionale altresì lo sviluppo delle zampe e delle dita in particolare. Il piumaggio è di un blu intenso, tranne il sottocoda, che è bianco, e un'ampia placca presente sulla fronte, rossa come il becco. Vive celato nei canneti che orlano le raccolte di acqua, fuggendo al minimo sospetto di pericolo. Si sposta agevolmente e rapidamente tra la densa vegetazione acquatica, ricorrendo piuttosto raramente al nuoto e al volo. Si ciba di vegetali, uova e piccoli di altri uccelli.

Porphyrio

porphyrio

Pollo sultano

Classificazione

scientifica

Regno: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Classe: Aves

Ordine: Gruiformes

Famiglia: Rallidae

Genere: Porphyrio

Specie: porphyrio

Nomenclatura binomiale Porphyrio porphyrio - Linnaeus, 1758

Il Pollo

sultano (Porphyrio porphyrio, Linnaeus 1758), è un uccello della famiglia dei

Rallidae. Il Pollo sultano ha 2 sottospecie:

Porphyrio porphyrio porphyrio

Porphyrio porphyrio aegyptiacus.

Caratterizzato con alcuni affini dalla robusta struttura, dal becco forte, molto alto e lungo quasi quanto la testa, da una grande callosità frontale e da lunghi e robusti piedi con dita grandi e ben distinte l'una dall'altra, il pollo sultano (Porphyrio porphyrio) ha inoltre ali di media lunghezza e coda breve. Misura circa quarantacinque centimetri di lunghezza complessiva, e ne ha ottanta di apertura alare; il suo abito è d'un bel turchino sulla faccia e sulla parte anteriore del collo, azzurro-indaco scuro all'occipite, alla nuca, sul basso del ventre e sulle cosce, e di questo stesso colore, ma più vivace, sulla parte inferiore del petto, sul dorso, sulle copritrici delle ali e sulle remiganti; la regione anale, viceversa, è bianca. Il colore degli occhi è rosso, il becco e la lamina frontale rosso-vivaci, il piede è giallo-rosso e uno stretto anello perioculare è giallo.

Il pollo sultano vive nelle località paludose e ricche d'acqua dell'Italia e della Spagna, nonché nel nord-ovest dell'Africa; nel nord-est di questo stesso continente è sostituito da una specie affine. La voce ricorda il canto dei galli e il chiocciare delle galline, ma nello stesso tempo è più forte e più profonda.

Fuori dell'epoca della riproduzione, quando nella palude non è possibile assalire uova e nidiacei, il pollo sultano è costretto ad accontentarsi di sostanze vegetali, cereali appena spuntati, erbe, foglie e varie specie di sementi.

Le coppie stabiliscono, ogni volta che è loro possibile, il proprio nido all'interno dei canneti, sovente a diretto contatto con l'acqua, e lo costruiscono intessendo sommariamente diverse qualità di sostanze vegetali palustri. Nel mese di maggio si può trovare la covata completa, composta di tre-cinque uova che sul fondo grigio-argento, carnicino o grigio-rosso, presentano macchie di diversi colori. Appena nati, i piccoli sono coperti d'un piumino azzurro-nero, e hanno il becco, la lamina frontale e i piedi azzurrognoli; vengono condotti intorno, istruiti e sorvegliati dai due genitori, e imparano ben presto a nuotare e a tuffarsi.

Oiseaux:

Gruiformes: Rallidés

Ordre : Gruiformes

Famille : Rallidés

Nom scientifique: Porphyrio porphyrio

Synonymes: poule sultane, porphyrion bleu, Purperkoet (Neerl), Purpurhuhn (Alle), Pollo sultano (Ital), Calamón Común (Espa), Purple Swamphen (Angl)

Biométrie

Taille: 45 à 50 cm

Envergure: 47 à 53 cm

Distribution: Espèce présente en France à l'état sauvage.

Statut: nicheur rare.

migrateur occasionnel, hivernant occasionnel. Espèce protégée.

Identification

La talève sultane possède un plumage bleu-violet soyeux, avec des reflets métalliques sur la gorge et la poitrine, sur lequel contraste la couleur blanche des plumes sous-caudales. Le bec est très grand, de forme triangulaire, et la mandibule supérieure volumineuse et recourbée, ce qui lui donne un aspect étrange. Il se prolonge jusqu'au sommet de la tête par une plaque frontale d'un rouge vif comme le bec et les longues pattes. Celles-ci se terminent par des doigts très longs aux griffes longues et effilées, spécialement celle du doigt postérieur. Les yeux sont également rouges. Les deux sexes sont similaires. Les juvéniles ont un plumage gris-ardoise bleuté, non brillant. La gorge et la face sont gris bleuté.

Chant

Son extrait des CD "Tous les Oiseaux d'Europe" de Jean C. Roché avec l'aimable autorisation de Sittelle et du CEBA. La voix de la talève sultane est difficile à définir. Le cri au moment de l'envol, rappelle beaucoup le son produit par une petite trompette. Il en existe plusieurs autres, possédant richesse et variété. Son cri est lancé depuis un endroit caché au plus dense de la végétation, et très souvent de nuit. Un autre de ses cris est une sorte de lamentation, une série de puissants sons continus qui vont crescendo, et atteignent une sonorité humaine impressionnante. Ce cri est émis en fin de journée et dans l'obscurité par un seul individu.D'autres cris sont au contraire plus brefs et rauques, allant du grognement au son d'une clochette, se terminant sur un dernier souffle de trompette. Beaucoup de ces cris sont émis en coeur par plusieurs talèves, et toujours de nuit, augmentant en intensité au fur et à mesure que l'excitation monte.

Habitat

La talève sultane aime les

marais où abondent les laîches, avec des alternances d'inondations et de sècheresses.

A ce moment-là, les oiseaux s'éloignent vers les lagunes côtières et les

fleuves, où ils passent le reste de l'été et l'automne, jusqu'à l'inondation

des marais avec les pluies et les crues. En Europe, sa distribution s'étend

à la péninsule ibérique, aux Baléares, à la Sardaigne et aux rives de la

Caspienne. La talève sultane est nicheuse en France depuis les années 1970

sur la côte méditerranéenne, notamment dans les phragmitaies des étangs

languedociens.

Comportements

La talève sultane a une étrange façon de se nourrir, en se servant de ses longs doigts. Elle se nourrit en marchant si elle se sent protégée, le long de la zone vaseuse bordant les roseaux. La nourriture est prise avec une patte, de préférence la droite. Les fragments végétaux sont tenus entre les doigts et élevés jusqu'à la moitié de la hauteur les séparant du bec. Si un fragment tombe, il est récupéré avec les doigts et non avec le bec, bien que souvent la tentative échoue. Les morceaux de racines ne pouvant être déplacés de cette façon, sont maintenus au sol avec les doigts et déchiquetés avec le bec. La talève sultane a été vue nourrissant ses petits avec la sève des roseaux, arrachant les tiges avec le bec et les saisissant avec les doigts, comme le ferait un perroquet.

Vol

La talève sultane vole relativement bien, avec les pattes pendantes, ce qui permet de l'identifier à bonne distance, et lui a valu d'être cataloguée « d'oiseau à l'aspect grotesque » et également « comme ressemblant à un intrus venant des tropiques ou une relique de la préhistoire. » (Vielliard-1974)

Nidification

La talève sultane commence la construction du nid avant que la végétation ait trop poussé. C'est un nid flottant construit au plus dense des roseaux. C'est une plate-forme de tiges sèches qui servent de base, recouvertes de larges feuilles, et surmontées d'un tunnel de feuilles aquatiques. Le nid est construit par les deux parents. On peut dire que c'est une énorme construction. C'est en réalité un tas de tiges de roseaux secs, soutenus sur le fond, et émergeant seulement de quelques centimètres. Chaque nid possède une ou deux rampes d'accès. La ponte a lieu en avril/mai. La femelle dépose les oeufs dans une sorte de coupe grossière. Ils sont assez grands (54,5 x 37 mm), brillants, la coquille est très claire et peut varier en tonalité. Elle est parsemée de taches violacées au fond et de points bruns. L'incubation dure environ 25 jours. Les poussins abandonnent le nid au bout de 4 ou 5 jours après l'éclosion. Ils sont couverts de duvet noir, les pattes sont rouges avec de longs doigts, et les griffes sont noires. Le bec est déjà très fort, gris foncé, rouge sang à la base. Peu de temps après apparaissent les premières plumes qui sont déjà bleu-violet mat, typiques des immatures. Ils grandissent rapidement, bien nourris par les parents. Le rouge du bec commence chez les jeunes par la plaque frontale, et gagnera le bec entier au mois d'août.

Régime

La talève sultane a un régime essentiellement végétarien, à base de tiges et de sève de plantes aquatiques. Parfois, elle peut consommer des poissons morts trouvés entre les canaux.

Protection / Menaces

Les talèves sultanes ont un impact important sur leur propre habitat, à la vitesse où elles consomment les racines. Parfois, l'aspect des marais où elles ont passées est spectaculaire. Cependant, le pouvoir de régénération de ces roseaux (typha, carex, scirpus, phragmites communis) est tel, qu'il est improbable que les talèves soient capables de détruire leur propre habitat. De plus, elles contribuent même à éviter sa trop grande expansion. La talève sultane, bien que protégée dans la plupart des endroits où elle vit, est quand même victime du vol de ses oeufs et de la chasse, et bien sûr, le drainage des marais et la pollution par les insecticides et le plomb restent malgré tout une menace.

www.oiseaux.net

Scientific

classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

Genus: Porphyrio

Species: porphyrio

Binomial name Porphyrio porphyrio - Linnaeus, 1758

The Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio), also known as the African Purple Swamphen or Purple Moorhen or Purple Gallinule, is a large bird in the family Rallidae. From its name in French, talève sultane, it is also sometimes known as the Sultana Bird. It should not be confused with the American Purple Gallinule, Porphyrio martinica. The common name in New Zealand, used for Porphyrio porphyrio melanotus is Pukeko, and is derived from the Maori name for the species.

There

are six or more subspecies of the Purple Swamphen, depending on the authority,

which differ mainly in the plumage colours. The races are:

P. p. porphyrio in Europe

P. p. madagascariensis in Africa

P. p. poliocephalus in tropical Asia

P. p. melanotus in much of Australasia

P. p. indicus in Indonesia

P. p. pulverulentus in the Philippines.

European birds are overall purple-blue, African and south Asian birds have a green back, and Australasian and Indonesian birds have black backs and heads. The Philippines subspecies is pale blue with a brown back. This chicken-sized bird, with its huge feet, bright plumage and red bill and frontal shield is unmistakable in its native range.

Some authorities separate various subspecies as full species, for example P. p. madagascariensis is split by Sinclair et al as African Purple Swamphen, P. madagascariensis.

Purple Swamphens are considered to be the ancestors of several island species including the extinct Lord Howe Swamphen and two species of Takahe in New Zealand. The Purple Swamphen itself, deriving from a later self-introduction, is a native of New Zealand, where it is called the Pukeko. Its range is thought to have expanded there after the arrival of humans as the numbers of Takahe declined to near-extinction levels.

The breeding habitat is warm reed beds across southernmost Europe, Africa, tropical Asia, and Australasia. The male has an elaborate courtship display,holding water weeds in his bill and bowing to the female with loud chuckles.

Pairs nest in a large pad of interwoven reed flags, etc., on a mass of floating debris or amongst matted reeds slightly above water level in swamps, clumps of rushes in paddocks or long unkempt grass. Multiple females lay in the one nest and share the incubation duties, the nest is composed of grass or similar materials. Each bird can lay 3-6 speckled eggs - pale yellowish stone to reddish buff, blotched and spotted with reddish brown. A communal nest may contain up to 12 eggs, incubation period is 24 days.

The Purple Swamphen prefers wet areas with high rainfall, swamps, lake edges and damp pastures. The birds often live in pairs and larger communities. It clambers through the reeds, eating the tender shoots and vegetable-like matter, they have been known to feed on invertebrates (like snails) and to rob eggs from nests and also eat ducklings. Sometimes they eat small fishes as well. They will often use one foot to bring food to their mouth rather than eat it on the ground. Where they are not persecuted they can become tame and be readily seen in towns and cities.

This species has a very loud explosive call, also described as a "raucous high-pitched screech, with a subdued musical tuk-tuk". It is particularly noisy during the breeding season. In spite of being clumsy in flight it can fly long distances, and it is also a good swimmer, especially for a bird without webbed feet.

Evidence from Pliny the Elder and other sources shows that the Romans kept Purple Swamphens as decorative birds at large villas and expensive houses. They were regarded as noble birds and were among the few birds that Romans did not eat.

Purple Swamphen is occasionally recorded as an escape from captivity in Britain and elsewhere. An introduced population exists in Florida, though state wildlife biologists are trying to eradicate the birds. See Purple Swamphens in North America.

Porfido è il termine originalmente applicato a una roccia dell'Egitto composta da cristalli di feldspati (silicati alluminiferi di potassio, sodio, calcio e bario, con tracce di altri elementi quali litio, cesio, rubidio, magnesio, ferro, titanio) incorporati in una matrice rossa o purpurea. Ora è chiamata porfido una qualunque roccia ignea che presenti cristalli ben definiti, cementati in una massa di materiale a grana relativamente più fine. La matrice a grana fine viene chiamata "pasta di fondo" e i cristalli più grandi "fenocristalli". La struttura cosiddetta porfirica può essere assunta da rocce di qualunque composizione mineralogica. (Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2006)

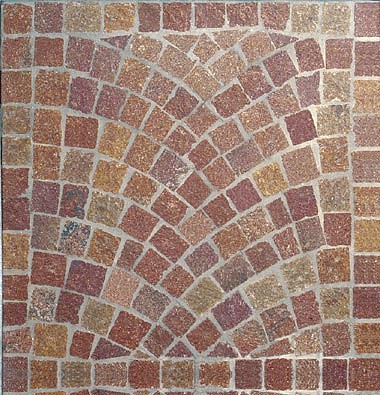

Pavimentazione in porfido

Il porfido è una roccia vulcanica effusiva: le più diffuse sulla crosta terrestre sono ignimbriti riolitiche e riodacitiche. Il porfido, petrograficamente, è formato da una pasta vetrosa o microcristallina di fondo, che ne costituisce più del 65% nella quale sono immersi piccoli cristalli (pezzatura 2/4 mm) in percentuale variabile tra il 30/35%. I cristalli più abbondanti sono quelli di quarzo, tanto che alla roccia viene attribuita anche la denominazione di "porfido quarzifero". Notevolmente inferiore è la presenza dei feldspati (silicati alluminiferi di potassio, sodio, calcio e bario, con tracce di altri elementi quali litio, cesio, rubidio, magnesio, ferro, titanio), esigua è quella delle miche. Il suo colore comunque varia dal grigio chiaro ad un marrone medio.

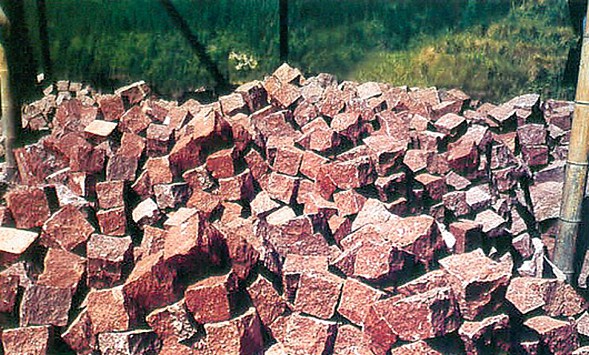

Porfido messicano

Questo tipo di pietra viene spesso utilizzata per applicazioni all'esterno poiché è molto resistente sia al forte freddo sia a temperature decisamente elevate. Lo possiamo trovare perciò in particolare in vari tipi di pavimentazioni (dai sanpietrini a lastre di modeste dimensioni) come anche utilizzato per rivestimenti, pareti ventilate e targhe.

Sicuramente già utilizzato dagli Etruschi (per la costruzione di altiforni) e dai Romani, il porfido grazie alle sue caratteristiche ebbe ampio utilizzo sia nell'arte sia in opere edili (come del resto anche oggi).

Uno dei più celebri luoghi di estrazione e lavorazione del porfido è il Trentino, ma anche in provincia di Varese, e in particolare a Cuasso al Monte si estrae porfido in una qualità contraddistinta dal colore rosso.

A piece of porphyry

Porphyry is a variety of igneous rock consisting of large-grained crystals, such as feldspar or quartz, dispersed in a fine-grained feldspathic matrix or groundmass. The larger crystals are called phenocrysts. In its non-geologic, traditional use, the term "porphyry" refers to the purple-red form of this stone, valued for its appearance.

The term "porphyry" is from Greek and means "purple". Purple was the color of royalty, and the "Imperial Porphyry" was a deep brownish purple igneous rock with large crystals of plagioclase. This rock was prized for various monuments and building projects in Imperial Rome and later. Pliny's Natural History affirmed that the "Imperial Porphyry" had been discovered at an isolated site in Egypt in AD 18, by a Roman legionnaire named Caius Cominius Leugas (Werner 1998). [Elio Corti didn't find these data] It came from a single quarry in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, from 600 million year old andesite of the Arabian-Nubian Shield. The road from the quarry westward to Qena (Roman Maximianopolis) on the Nile, which Ptolemy put on his second-century map, was described first by Strabo, and it is to this day known as the Via Porphyrites, the Porphyry Road, its track marked by the hydreumata, or watering wells that made it viable in this utterly dry landscape. Porphyry was extensively used in Byzantine imperial monuments, for example in Hagia Sophia and in the "Porphyra", the official delivery room for use of pregnant Empresses in the Great Palace of Constantinople.

After the fourth century the quarry was lost to

sight for many centuries. The scientific members of the French Expedition

under Napoleon sought for it in vain, and it was only when the Eastern Desert

was reopened for study under Muhammad Ali that the site was rediscovered by

Burton and Wilkinson in 1823.

Subsequently the name was given to igneous rocks with large crystals. Porphyry

now refers to a texture of igneous rocks. Its chief characteristic is a large

difference between the size of the tiny matrix crystals and other much larger

crystals, called phenocrysts. Porphyries may be aphanites or phanerites, that

is, the groundmass may have invisibly small crystals, like basalt, or the

individual crystals of the groundmass may be easily distinguished with the

eye, as in granite. Many types of igneous rocks may display porphyrytic

texture.

Formation

Porphyry deposits are formed when a column of rising magma is cooled in two stages. In the first stage, the magma is cooled slowly deep in the crust, creating the large crystal grains, with a diameter of 2 mm or more. In the final stage, the magma is cooled rapidly at relatively shallow depth or as it erupts from a volcano, creating small grains that are usually invisible to the unaided eye. The cooling also leads to a separation of dissolved metals into distinct zones. This process is one of the main reasons for the existence of rich, localised metal ore deposits such as those of gold, copper, molybdenum, lead, tin, zinc and tungsten.

Porphyry in history

All the porphyry columns in Rome, the red porphyry togas on busts of emperors, the porphyry panels in the revetment of the Pantheon, as well as the altars and vases and fountain basins reused in the Renaissance and dispersed as far as Kiev, all came from the one quarry at Mons Porphyritis ("Porphyry Mountain", the Arabic Jabal Abu Dukhan), which seems to have been worked intermittently between 29 and 330, when Constantine I celebrated the founding of his capital Constantinople with a 30-meter (100') pillar, built of seven stacked porphyry drums, which still stands. A triumphant last use were the eight monolithic columns of porphyry that support exedrae (semicircular niches) in Hagia Sophia. Justinian's chronicler, Procopius, called the columns "a meadow with its flowers in full bloom, surely to make a man marvel at the purple of some and at those on which the crimson glows." (noted by Werner).

The porphyry portal of the "church house" at Colditz Castle, Saxony, designed by Andreas Walther II (1584), is a clear example of the exuberance of "Antwerp Mannerism".

Byzantine historians distinguish two sorts of emperors: those who won power through a coup and those "born to the purple". These porphyrogenites were born to the imperial family in a room in the Great Palace veneered with purple porphyry, as described by Anna Comnena, daughter of the eleventhth-century emperor Alexius I.

The imperial families were entombed in the purple as well, beginning with Nero, who was the first to be immured in a porphyry sarcophagus. Roman sarcophagi were re-used for imperial burials in Sicily: the porphyry sarcophagi of Holy Roman Emperors Frederick II and Henry IV and king William I of Sicily and the Empress Constance are preserved in the cathedrals of Palermo and Monreale.

The Romans used the Imperial porphyry for the monolithic pillars of Baalbek's Temple of Heliopolis in Lebanon. Today there are at least 134 porphyry columns in buildings around Rome, all reused from imperial times, since the stone is not naturally present in Italy, and countless altars, basins and other objects.

The baptismal font in the Cathedral of Magdeburg is made of rose porphyry from Gebel Abu Dokhan near Hurghada, Egypt

Porphyry was used extensively for decoration in Germany, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. This can be seen in the Mannerist style sculpted portal outside the chapel entrance in Colditz Castle.

Louis XIV King of France obtained the largest collection of porphyry by acquiring the Borghese collection. In 1840, Bonapartists recovered the body of Napoleon I from Saint Helena and intended to bury it in a porphyry sarcophagus in Les Invalides, Paris. However, the Egyptian quarry was not available and a similar red quartzite from Finland was chosen, in spite of its purchase from the Russian Empire, an enemy of France.

Rhomb porphyry

Rhomb porphyry is a volcanic rock with gray-white large porphyritic rhomb shaped phenocrysts enbedded in a very fine grained red-brown matrix. The composition of rhomb porphyry place it in the trachyte - latite classification of the QAPF diagram.

Rhomb porphyry lavas are known only from three rift areas: The East African Rift (including Mount Kilimanjaro), Mount Erebus near the Ross Sea in Antarctica, and the Oslo graben in Norway.