Lessico

Selinunte

Didracma

di Selinunte ca 540/530-510 aC

al dritto l'emblema della città

la foglia di sélinon - il sedano selvatico - Apium graveolens

al rovescio un quadrato incuso - in incavo anziché in rilievo

In greco Selinoûs-oûntos, in latino Selinus-nuntis, gli

abitanti Selinuntii-orum. Il nome deriva dal sedano

selvatico (sélinon

in greco) che i coloni vi trovarono in abbondanza![]() e che era raffigurato come emblema sulle monete della città

e che era raffigurato come emblema sulle monete della città![]() .

Il sostantivo greco neutro sélinon viene tradotto con apio

.

Il sostantivo greco neutro sélinon viene tradotto con apio![]() , sedano,

prezzemolo. Il nome scientifico del prezzemolo è Petroselinum hortense,

dal greco petrosélinon, sedano che nasce tra le pietre, da pétra,

pietra+sélinon, sedano.

, sedano,

prezzemolo. Il nome scientifico del prezzemolo è Petroselinum hortense,

dal greco petrosélinon, sedano che nasce tra le pietre, da pétra,

pietra+sélinon, sedano.

Antica città della Magna Grecia situata

in Sicilia sulla costa sudoccidentale, allo sbocco del fiume Selinunte (ora

Madione)

e a pochi km a ovest del fiume Ipsas![]() (oggi Belice),

vicino al moderno villaggio di Marinella (Trapani)

le cui

rovine si trovano 13 km a SSE di Castelvetrano (Trapani). Ambedue i fiumi

compaiono come divinità sulle monete dell'antica Selinunte: Selinos

e Hypsas.

(oggi Belice),

vicino al moderno villaggio di Marinella (Trapani)

le cui

rovine si trovano 13 km a SSE di Castelvetrano (Trapani). Ambedue i fiumi

compaiono come divinità sulle monete dell'antica Selinunte: Selinos

e Hypsas.

Fondata nella seconda metà del sec. VII aC da un gruppo di coloni calcidesi di Megara Iblea (antica città greca situata sulla costa orientale della Sicilia poco lontano da Siracusa), rappresentò l'avamposto occidentale dei Greci sulla costa meridionale della Sicilia.

Nel corso del sec. V ebbe frequenti scontri con la potente vicina Segesta

(la città

degli Elimi, antica popolazione proveniente dal Vicino Oriente, forse

dall'Anatolia)

che

poteva contare sull'aiuto di Cartagine. Nonostante l'appoggio dei Siracusani,

ai quali rimase fedele anche durante la spedizione ateniese in Sicilia,

Selinunte nel 409 fu distrutta dai Cartaginesi a opera dei quali subì nel 250

durante la

prima guerra punica![]() (264-241

aC)

una nuova e definitiva distruzione con il trasferimento dei cittadini a

Lilibeo, l'odierna

Marsala.

(264-241

aC)

una nuova e definitiva distruzione con il trasferimento dei cittadini a

Lilibeo, l'odierna

Marsala.

Il Belice (in passato Ipsas, Hypsâs in greco) è un fiume della Sicilia sud occidentale lungo 107 km (il 3° della regione dopo Imera Meridionale e Simeto) e con un bacino idrografico di 964 km², uno dei maggiori della Sicilia meridionale per estensione. Nel suo corso attraversa il territorio di tre province: Agrigento, Palermo e Trapani, interessando i comuni di Menfi, Montevago, Camporeale, Partanna, Poggioreale e Castelvetrano.

Il Belice si forma dall'unione di due rami, in località Carrubbella, nei pressi di Poggioreale: il Belice Destro (55 km) che nasce presso Piana degli Albanesi, e il Belice Sinistro (57 km), che scende invece dalla Rocca Busambra. Dopo la confluenza il fiume, che si sviluppa lungo la direttrice NE-SO da Palermo fino alla costa mediterranea tra Punta Granitola e Capo San Marco, raccoglie le acque del torrente Senore percorrendo ancora circa 50 Km fino alla foce che avviene nel Mar Mediterraneo. La lunghezza dell'asta principale del fiume è dunque pari a 107 Km, compresi i 57 Km del Fiume Belice Sinistro.

Il Belice risente del regime tipico dei corsi d'acqua siculi, ovvero torrentizio, con grosse piene in autunno e inverno e magre quasi totali in estate. La media annua (c. 4,5 mc/sec.) è molto modesta in rapporto all'estensione di bacino.

Presso la confluenza dei due rami destro e sinistro, che ricade nel territorio comunale di Contessa Entellina, è stata istituita in tempi recenti la Riserva Naturale Integrale Grotta di Entella. La Grotta di Entella, che è il motivo dell'istituzione della riserva, si sviluppa all'interno della Rocca (557 metri slm), che è un rilievo isolato proprio a monte della confluenza del Belice Sinistro con il Belice Destro. In tutto il promontorio della Rocca non sono presenti corsi d'acqua visibili alla superficie ma le acque piovane si infiltrano nel sottosuolo andando ad alimentare il vallone di Petraro e degli affluenti del Belice Sinistro contribuendo ad accrescere la portata del fiume.

Nella prima metà degli anni ottanta il Consorzio per l'Alto e Medio Belice ha costruito uno sbarramento sul Belice Sinistro, ai piedi della Rocca di Entella, che ha dato origine al lago Garcia, che oltre a servire per l'agricoltura è diventato un punto di riferimento per lo svernamento degli uccelli migratori. Nei pressi della Rocca di Entella vi è anche l'importante sito archeologico di Entella.

L'ultimo tratto del fiume fra Marinella e Porto Palo, situato a est delle rovine di Selinunte fa parte della della Riserva Naturale Foce del Fiume Belice.

Hypsas is today called the Belice River, near the ancient city of Selinus, on the banks of which stood the ancient city of Inycum (probably a mere dependency of Selinus, principally known from its connection with the mythical legends concerning Minos and Daedalus). The Belice is a river, 77 km in length, of western Sicily. From its main source near Piana degli Albanesi it runs south and west for 45.5 km as the Belice Destra (Right Belice) until it is joined on the left by its secondary branch, the 42 km Belice Sinistro (Left Belice), which rises on the slopes of Rocca Busambra. The Belice proper then flows for another 30 km or so before entering the Strait of Sicily to the east of the ancient Greek archaeological site of Selinus.

The middle section of the Belice valley was hit by a severe earthquake in January 1968 which completely destroyed numerous centres of population, including Gibellina, Montevago and Salaparuta. 370 people died, a thousand were injured and some 70,000 people were made homeless.

Selinunte

Selinunte (greco Selinoûs, latino Selinus) era una antica città greca sulla costa sud-occidentale della Sicilia. Il sito archeologico è composto da cinque templi costruiti intorno a un'acropoli. Dei cinque templi solo il tempio E (il cosiddetto tempio di Era) è stato ricostruito.

Secondo

Tucidide![]() ,

Selinunte fu fondata verso la metà del VII secolo aC da coloni greci

provenienti da Megara Iblea, colonia greca di Megara sulla costa occidentale

della Sicilia. Il sito scelto stava sulla costa del Mar Mediterraneo, tra le

due valli fluviali del Belice e del Modione.

,

Selinunte fu fondata verso la metà del VII secolo aC da coloni greci

provenienti da Megara Iblea, colonia greca di Megara sulla costa occidentale

della Sicilia. Il sito scelto stava sulla costa del Mar Mediterraneo, tra le

due valli fluviali del Belice e del Modione.

La città

ebbe una vita breve (circa 200 anni). In questo periodo la sua popolazione

crebbe fino a raggiungere le 25.000 unità. Il nome deriva dal sedano

selvatico![]() (sélinon

in greco) che i coloni vi trovarono in abbondanza. Una pianta di sedano era

raffigurata anche sulle monete coniate più tardi a Selinunte.

(sélinon

in greco) che i coloni vi trovarono in abbondanza. Una pianta di sedano era

raffigurata anche sulle monete coniate più tardi a Selinunte.

La città

fu l'avamposto occidentale della cultura greca in Sicilia. Si alleò con

Cartagine, soprattutto per assicurarsi protezione contro la vicina città di

Segesta. Ma dopo la disastrosa spedizione in Sicilia degli Ateniesi (415-413

aC) cambiarono gli equilibri: Segesta, prima alleata di Atene, riuscì ad

assicurarsi l'alleanza con i Cartaginesi. I Selinuntini non avevano colto i

segni del cambiamento e invasero i territori segestani, che credevano ormai

privi di protezione. Invece la reazione di Cartagine fu drastica: la città

venne assediata per nove giorni da un esercito di 100.000 Cartaginesi e,

secondo Diodoro Siculo![]() ,

distrutta completamente. Su 25.000 abitanti 16.000 morirono e 5.000 furono

fatti prigionieri. Selinunte fu successivamente ricostruita da coloni greci e

punici. Nel 250 aC Roma, dopo aver vinto la prima guerra punica

,

distrutta completamente. Su 25.000 abitanti 16.000 morirono e 5.000 furono

fatti prigionieri. Selinunte fu successivamente ricostruita da coloni greci e

punici. Nel 250 aC Roma, dopo aver vinto la prima guerra punica![]() ,

distrusse una seconda volta la città, che non si sarebbe più ripresa.

,

distrusse una seconda volta la città, che non si sarebbe più ripresa.

Veduta dell'acropoli di Selinunte dalla collina orientale

I ruderi della città si trovano sul territorio del comune di Castelvetrano, nella parte meridionale della provincia di Trapani. Tutto il terreno interessato forma oggi un parco archeologico della dimensione di ca. 40 ettari. Il parco archeologico di Selinunte è oggi considerato il più ampio e imponente d’Europa: si estende per 1740 km quadrati e comprende numerosi templi, santuari e altari. Le sculture trovate negli scavi di Selinunte si trovano soprattutto nel Museo Nazionale Archeologico di Palermo. Fa eccezione l'opera più famosa, l'Efebo di Selinunte, che è oggi esposto al Museo Comunale di Castelvetrano.

I resti di Selinunte sono divisibili in tre aree principali, l'Acropoli, la collina orientale, e il santuario della Malophoros. È il santuario di Demetra Malophoros, il cui culto, assieme a quello della figlia Persefone, era molto diffuso in Sicilia. L'area dell'acropoli era destinata alle divinità. Una parte, durante il periodo greco-punico, era adibita a zona abitata.

La collina orientale: in questa zona sono presenti i templi E, F e G. Il tempio E è il più meridionale con dimensioni di 67,82m x 25,33m, ed è databile alla metà del V secolo aC. Il tempio F è il più antico, risale al 530 aC. Il tempio G, con le sue dimensioni pari a 50,07 m x 100,12 m uno dei più grandi fra tutti i templi greci, non è mai stato ultimato.

Selinunte

la città del prezzemolo selvatico

Il suo nome deriva probabilmente da sélinon, il nome dato dai greci al prezzemolo selvatico assai diffuso nella zona e il cui disegno era inciso sulle monete della città. La storia di Selinunte – colonia greca che conobbe un periodo di grande floridezza nel V secolo aC – e le vicende degli scavi nel suo importante sito archeologico sono ripercorse nel brano seguente, tratto dalla Guida Rossa Sicilia del Touring Club Italiano.

Selinunte venne fondata da Megara Hyblaea nel 628 aC e fu la colonia greca più occidentale della Sicilia. Il nome si fa derivare da quello del prezzemolo selvatico (Apium graveolens o petroselinum), detto dai Greci sélinon, assai diffuso nella regione e che si trova inciso come emblema locale sulle monete. I monumenti grandiosi dimostrano che la città raggiunse, nel secolo V aC, uno straordinario sviluppo. Mantenne dapprima buoni rapporti con la vicina e forte Cartagine, ma dopo la battaglia di Himera strinse alleanza con Siracusa, cui rimase sempre fedele. La sua flotta partecipò alla guerra peloponnesiaca. In una delle frequenti contese con Segesta, questa invocò l’aiuto di Cartagine, la quale inviò un esercito di centomila uomini, comandato da Annibale, figlio di Gisgone. Selinunte soccombette, non essendole giunti in tempo gli attesi soccorsi di Siracusa e di Agrigento. Si narra che 16.000 cittadini fossero uccisi, 5000 fatti schiavi, 2600 riparati ad Agrigento. La città fu distrutta (409 aC).

Dopo due anni, il siracusano Ermocrate, bandito dalla sua città, volle far risorgere Selinunte, ripopolandola e restaurandola; fu però costretto ad abbandonarla quasi subito. Dopo qualche decennio di alterne vicende, la città visse, solo sull’Acropoli, per circa un secolo e mezzo, sotto il dominio politico cartaginese, fino a che, alla fine della prima guerra punica, fu completamente abbandonata.

Pare che, nell’Alto Medioevo, vi dimorassero eremiti e comunità religiose. Un violento terremoto (probabilmente in epoca bizantina) finì per ridurre a un cumulo di rovine i monumenti dell’antica città, della quale si perdette anche il nome. Nell’epoca araba vi era un villaggio chiamato dal cronista Edrisi “Rahl’-al-‘Asnam” (villaggio dei pilastri); più tardi è ricordato in un documento del 1503 col nome di “Terra di Pulci” (forse corruzione di Polluce). Fu il Fazello (1498-1570) a riconoscervi la sede dell’antica Selinunte. Essa servì per secoli come cava di pietre dei templi orientali. Le devastazioni continuarono anche dopo un divieto di re Ferdinando III (1779) e cessarono solo quando il governo italiano vi pose una custodia permanente.

Nonostante le difficili comunicazioni, le rovine furono visitate fin dal Settecento da studiosi e viaggiatori. Vi iniziò scavi, con poco frutto, l’inglese Fagan, console generale a Palermo (1809-10). Nel 1822-23 gli archeologi inglesi William Harris e Samuel Angell (il primo, colpito da malaria, moriva a Palermo) esplorarono il tempio C e scoprirono alcune metope dei templi C e E, sulle quali l’Angell, con l’aiuto di Thomas Evans e del palermitano barone Pietro Pisani, pubblicò un libro (1826). Nel 1824 l’archeologo tedesco Hittorf, il suo discepolo Zanth e l’archeologo Stier misurarono e disegnarono le rovine.

Nel 1831 Domenico Lo Faso duca di Serradifalco, essendo a capo della organizzazione archeologica statale, vi riprese gli scavi con l’aiuto dello scultore Valerio Villareale e dell’architetto Francesco Saverio Cavallari, scoprendo le metope del tempio E. Nel 1864 il governo italiano vi istituì una direzione di antichità, affidata al Cavallari, che continuò le ricerche scoprendo, fra l’altro, le 2 principali strade dell’Acropoli e la necropoli di Manicalunga. L’opera del Cavallari fu continuata dai successori: Salinas, Patricolo, Gabrici. Quest’ultimo nel 1915 continuò gli scavi sistematici della Gàggera scoprendo la parte nord del santuario della Malophoros, e più tardi dell’Acropoli, ove scoprì una metopa antichissima (1924). Nel 1925-27, grazie al mecenatismo di Felice Flora, furono innalzate le colonne del lato nord del tempio C. Il Cultrera vi lavorò negli anni successivi; solo dopo la guerra, con finanziamenti della Regione Siciliana, sono state riprese dalla Soprintendenza annuali opere di restauro e di scavo, volte all’esplorazione sistematica degli isolati dell’Acropoli e della cinta delle fortificazioni, quest’ultima ormai tutta scoperta.

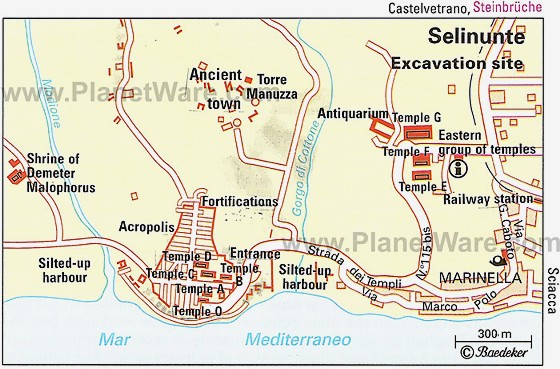

Selinunte sorgeva sopra una spianata a circa 47 metri, posta fra due avvallamenti, un tempo probabilmente insenature della costa: la valle del Modione, l’antico Selinon, oggi canalizzato, a ovest, e la bassura paludosa detta Gorgo di Cottone o Galici a est. La spianata è tuttora divisa in due parti congiunte come da un istmo: sull’altura a sud, che precipita sul mare, era la città primitiva e l’Acropoli di cui restano i templi A, B, C, D e O; su quella a nord era la città propriamente detta. A est del Gorgo, sopra un’altra spianata a 30-50 metri rimangono i grandiosi templi E, F, G. Finora sono state trovate tre necropoli: una a nord della città, tra le attuali case Galera e Bagliazzo; una seconda a est dell’Acropoli; la terza, assai più vasta, a ovest del Modione. Tutto questo vasto insieme fu coperto in gran parte dalle sabbie mobili, che tuttora invadono le colture sulla collina a ovest di Selinunte. I templi avevano tutti, secondo l’uso, la facciata rivolta a est. Si indicano con lettere dell’alfabeto perché non è noto a quali divinità fossero consacrati, tranne che per E (Hera) e per G (Zeus).

Guida d’Italia. Sicilia, Touring Club Italiano, Milano 1989

Selinunte (Greek: Selinoûs; Latin: Selinus) is an ancient Greek archaeological site situated on the south coast of Sicily between the valleys of the rivers Belice and Modione in the province of Trapani. The archaeological site contains five temples centered on an acropolis. Of the five temples, only temple E, the so-called "Temple of Hera" has been re-erected.

History

Selinus was one of the most important of the Greek colonies in Sicily, situated on the southwest coast of that island, at the mouth of the small river of the same name, and 6.5 km west of that of the Hypsas (the modern Belice River). It was founded, as we learn from Thucydides, by a colony from the Sicilian city of Megara, or Megara Hyblaea, under the conduct of a leader named Pammilus, about 100 years after the settlement of that city, with the addition of a fresh body of colonists from the parent city of Megara in Greece. (Thuc. vi. 4, vii. 57; Scymn. Ch. 292; Strabo vi. p. 272.) The date of its foundation cannot be precisely fixed, as Thucydides indicates it only by reference to that of the Sicilian Megara, which is itself not accurately known, but it may be placed about 628 BCE. Diodorus indeed would place it 22 years earlier, or 650 BCE, and Hieronymus still further back, 654 BCE; but the date given by Thucydides, which is probably entitled to the most confidence, is incompatible with this earlier epoch. (Thuc. vi. 4; Diod. xiii. 59; Hieron. Chron. ad ann. 1362; Clinton, Fast. Hell. vol. i. p. 208.) The name is supposed to have been derived from the quantities of wild parsley (sélinon) which grew on the spot; and for the same reason a leaf of this parsley was adopted as the symbol of their coins.

Selinus was the most westerly of the Greek colonies in Sicily, and for this reason was early brought into contact and collision with the Carthaginians and the native Sicilians in the west and northwest of the island. The former people, however, do not at first seem to have offered any obstacle to their progress; but as early as 580 BCE we find the Selinuntines engaged in hostilities with the people of Segesta (a non-Hellenic city), whose territory bordered on their own. (Diod. v. 9). The arrival of a body of emigrants from Rhodes and Cnidus who subsequently founded Lipara, and who lent their assistance to the Segestans, for a time secured the victory to that people; but disputes and hostilities seem to have been of frequent occurrence between the two cities, and it is probable that in 454 BCE, when Diodorus speaks of the Segestans as being at war with the Lilybaeans (modern Marsala) (xi. 86), that the Selinuntines are the people really meant. The river Mazarus, which at that time appears to have formed the boundary between the two states, was only about 25 km west of Selinus; and it is certain that at a somewhat later period the territory of Selinus extended to its banks, and that that city had a fort and emporium at its mouth. (Diod. xiii. 54.) On the other side its territory certainly extended as far as the Halycus (modern Platani), at the mouth of which it had founded the colony of Minoa, or Heracleia, as it was afterwards termed. (Herod. v. 46.) It is evident, therefore, that Selinus had early attained to great power and prosperity; but we have very little information as to its history. We learn, however, that, like most of the Sicilian cities, it had passed from an oligarchy to a despotism, and about 510 BCE was subject to a despot named Peithagoras, from whom the citizens were freed by the assistance of the Spartan Euryleon, one of the companions of Dorieus: and thereupon Euryleon himself, for a short time, seized on the vacant sovereignty, but was speedily overthrown and put to death by the Selinuntines. (Herod. v. 46.) We are ignorant of the causes which led the Selinuntines to abandon the cause of the other Greeks, and take part with the Carthaginians during the great expedition of Hamilcar, 480 BCE; but we learn that they had even promised to send a contingent to the Carthaginian army, which, however did not arrive till after its defeat. (Diod. xi. 21, xiii. 55.) The Selinuntines are next mentioned in 466 BCE, as co-operating with the other free cities of Sicily in assisting the Syracusans to expel Thrasybulus (Id. xi. 68); and there is every reason to suppose that they fully shared in the prosperity of the half century that followed, a period of tranquillity and opulence for most of the Greek cities in Sicily. Thucydides speaks of Selinus just before the Athenian expedition as a powerful and wealthy city, possessing great resources for war both by land and sea, and having large stores of wealth accumulated in its temples. (Thuc. vi. 20.) Diodorus also represents it at the time of the Carthaginian invasion, as having enjoyed a long period of tranquillity, and possessing a numerous population. (Diod. xiii. 55.)

In 416 BCE, a renewal of the old disputes between Selinus and Segesta became the occasion of the great Athenian expedition to Sicily. The Selinuntines were the first to call in the powerful aid of Syracuse, and thus for a time obtained the complete advantage over their enemies, whom they were able to blockade both by sea and land; but in this extremity the Segestans had recourse to the assistance of Athens. (Thuc. vi. 6; Diod. xii. 82.) Though the Athenians do not appear to have taken any measures for the immediate relief of Segesta, it is probable that the Selinuntines and Syracusans withdrew their forces at once, as we hear no more of their operations against Segesta. Nor does Selinus bear any important part in the war of which it was the immediate occasion. Nicias indeed proposed, when the expedition first arrived in Sicily (415 BCE), that they should proceed at once to Selinus and compel that city to submit on moderate terms (Thuc. vi. 47); but this advice being overruled, the efforts of the armament were directed against Syracuse, and the Selinuntines in consequence bore but a secondary part in the subsequent operations. They are, however, mentioned on several occasions as furnishing auxiliaries to the Syracusans; and it was at Selinus that the large Peloponnesian force sent to the support of Gylippus landed in the spring of 413 BCE, having been driven over to the coast of Africa by a tempest. (Thuc. vii. 50, 58; Diod. xiii. 12.)

The defeat of the Athenian armament left the Segestans apparently at the mercy of their rivals; they in vain attempted to disarm the hostility of the Selinuntines by ceding without further contest the frontier district which had been the original subject of dispute. But the Selinuntines were not satisfied with this concession, and continued to press them with fresh aggressions, for protection against which they sought assistance from Carthage. This was, after some hesitation, accorded them, and a small force sent over at once, with the assistance of which the Segestans were able to defeat the Selinuntines in a battle. (Diod. xiii. 43, 44.) But not content with this, the Carthaginians in the following spring (409 BCE) sent over a vast army amounting, according to the lowest estimate, to 100,000 men, with which Hannibal Mago (the grandson of Hamilcar that was killed at Himera) landed at Lilybaeum, and from thence marched direct to Selinus. The Selinuntines were wholly unprepared to resist such a force; so little indeed had they expected it that the fortifications of their city were in many places out of repair, and the auxiliary force which had been promised by Syracuse as well as by Agrigentum (modern Agrigento) and Gela, was not yet ready, and did not arrive in time. The Selinuntines, indeed, defended themselves with the courage of despair, and even after the walls were carried, continued the contest from house to house; but the overwhelming numbers of the enemy rendered all resistance hopeless; and after a siege of only ten days the city was taken, and the greater part of the defenders put to the sword. Of the citizens of Selinus we are told that 16,000 were slain, 5,000 made prisoners, and 2,600 under the command of Empedion escaped to Agrigentum. (Diod. xiii. 54-59.) Shortly after Hannibal destroyed the walls of the city, but gave permission to the surviving inhabitants to return and occupy it, as tributaries of Carthage, an arrangement which was confirmed by the treaty subsequently concluded between Dionysius, tyrant of Syracuse, and the Carthaginians, in 405 BCE. (Id. xiii. 59, 114.) In the interval a considerable number of the survivors and fugitives had been brought together by Hermocrates, and established within its walls. (Id. 63.) There can be no doubt that a considerable part of the citizens of Selinus availed themselves of this permission, and that the city continued to subsist under the Carthaginian dominion; but a fatal blow had been given to its prosperity, which it undoubtedly never recovered.

The Selinuntines are again mentioned in 397 BCE as declaring in favour of Dionysius during his war with Carthage (Diod. xiv. 47); but both the city and territory were again given up to the Carthaginians by the peace of 383 BCE (Id. xv. 17); and though Dionysius recovered possession of it by arms shortly before his death (Id. xv. 73), it is probable that it soon again lapsed under the dominion of Carthage. The Halycus, which was established as the eastern boundary of the Carthaginian dominion in Sicily by the treaty of 383 BCE, seems to have generally continued to be so recognised, notwithstanding temporary interruptions; and was again fixed as their limit by the treaty with Agathocles in 314 BCE. (Id. xix. 71.) This last treaty expressly stipulated that Selinus, as well as Heracleia and Himera, should continue subject to Carthage, as before. In 276 BCE, however, during the expedition of Pyrrhus to Sicily, the Selinuntines voluntarily submitted to that monarch, after the capture of Heracleia. (Id. xxii. 10. Exc. H. p. 498.) During the First Punic War we again find Selinus subject to Carthage, and its territory was repeatedly the theater of military operations between the contending powers. (Id. xxiii. 1, 21; Pol. i. 39.) But before the close of the war (about 250 BCE), when the Carthaginians were beginning to contract their operations, and confine themselves to the defence of as few points as possible, they removed all the inhabitants of Selinus to Lilybaeum and destroyed the city. (Diod. xxiv. 1. Exc. H. p. 506.)

It seems certain that it was never rebuilt. Pliny indeed, mentions its name (Selinus oppidum, iii. 8. s. 14), as if it still existed as a town in his time, but Strabo distinctly classes it with the cities which were wholly extinct; and Ptolemy, though he mentions the river Selinus, has no notice of a town of the name. (Strab. vi. p. 272; Ptol. iii. 4. § 5.) The Thermae Selinuntiae (at modern Sciacca), which derived their name from the ancient city, and seem to have been much frequented in the time of the Romans, were situated at a considerable distance, 30 km, from Selinus: they are sulphureous springs, still much valued for their medical properties, and dedicated, like most thermal waters in Sicily, to San Calogero. At a later period they were called the Aquae Labodes or Larodes, under which name they appear in the Itineraries. (Itin. Ant. p. 89; Tab. Peut.)

Modern situation and ruins

By the 19th century, the site of the ancient city was wholly desolate, with the exception of a solitary guardhouse, and the ground for the most part thickly overgrown with shrubs and low brushwood; but the remains of the walls could be distinctly traced throughout a great part of their circuit. They occupied the summit of a low hill, directly abutting on the sea, and bounded on the west by the marshy valley through which flows the river Madiuni, the ancient Selinus; on the east by a smaller valley or depression, also traversed by a small marshy stream, which separates it from a hill of similar character, where the remains of the principal temples are still visible. The space enclosed by the existing walls is of small extent, so that it is probable the city in the days of its greatness must have covered a considerable area without them: and it has been supposed by some writers that the present line of walls is that erected by Hermocrates when he restored the city after its destruction by the Carthaginians. (Diod. xiii. 63.) No trace is, however, found of a more extensive circuit, though the remains of two lines of wall, evidently connected with the port, are found in the small valley east of the city. Within the area surrounded by the walls are the remains of three temples, all of the Doric order, and of an ancient style; none of them were standing until the temple designated "Temple E" was re-erected in the 20th century, but the foundations of them all remain, together with numerous portions of columns and other architectural fragments, sufficient to enable one to restore the plan and design of all three without difficulty. The largest of them is 70 m long by 25 m broad, and has 6 columns in front and 18 in length, a very unusual proportion. All these are hexastyle and peripteral. Besides these three temples there is a small temple or Aedicula, of a different plan, but also of the Doric order. No other remains of buildings, beyond mere fragments and foundations, can be traced within the walls; but the outlines of two large edifices, built of squared stones and in a massive style, are distinctly traceable outside the walls, near the northeast and northwest angles of the city, though their nature or purpose is unclear.

But much the most remarkable of the ruins at Selinus are those of three temples on the hill to the east, which do not appear to have been included in the city, but, as was often the case, were built on this neighbouring eminence, so as to front the city itself. All these temples are considerably larger than any of the three above described; and the most northerly of them is one of the largest of which we have any remains. It had 8 columns in front and 17 in the sides, and was of the kind called pseudo-dipteral. Its length was 110 m, and its breadth 55 m, so that it was actually longer than the great Temple of Olympian Zeus at Agrigentum, though not equal to it in breadth. From the columns being only partially fluted, as well as from other signs, it is clear that it never was completed; but all the more important parts of the structure were finished, and it must have certainly been one of the most imposing fabrics in antiquity. Only three of the columns are now standing, and these imperfect; but the whole area is filled up with a heap of fallen masses, portions of columns, capitals, and other huge architectural fragments, all of the most massive character, and forming, as observed by Swinburne, one of the most gigantic and sublime ruins imaginable. The two other temples are also prostrate, but the ruins have fallen with such regularity that the portions of almost every column lie on the ground as they have fallen; and it is not only easy to restore the plan and design of the two edifices, but it appears as if they could be rebuilt with little difficulty. These temples, though greatly inferior to their gigantic neighbour, were still larger than that at Segesta, and even exceed the great temple of Neptune at Paestum; so that the three, when standing, must have presented a spectacle unrivalled in antiquity. All these buildings may be safely referred to a period anterior to the Carthaginian conquest (409 BCE), though the three temples last described appear to have been all of them of later date than those within the walls of the city. This is proved, among other circumstances, by the sculptured metopes, several of which have been discovered and extricated from among the fallen fragments. Of these sculptures, those which belonged to the temples within the walls, present a very peculiar and archaic style of art, and are universally recognised as among the earliest extant specimens of Greek sculpture. (They are figured by Müller, Denkmäler, pl. 4, 5, as well as in many other works, and casts of them are in the British Museum.) Those, on the contrary, which have been found among the ruins of the temple on the opposite hill, are of a later and more advanced style, though still retaining considerable remains of the stiffness of the earliest art. Besides the interest attached to these Selinuntine metopes from their important bearing on the history of Greek sculpture, the remains of these temples are of value as affording the most unequivocal testimony to the use of painting, both for the architectural decoration of the temples, and as applied to the sculptures with which they were adorned. A very full and detailed account of the ruins at Selinus is given in the Duke of Serra di Falco's Antichità Siciliane, vol. ii., which contains a detailed plan of the site. A more general description of them will be found in Swinburne's Travels, vol. ii. pp. 242-45; Smyth's Sicily, pp. 219-21; and other works on Sicily in general. A plan is also presented in Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.

Coinage

The coins of Selinus are numerous and various. The earliest, as already mentioned, bear merely the figure of a parsley-leaf on the obverse. Those of somewhat later date represent a figure sacrificing on an altar, which is consecrated to Aesculapius, as indicated by a cock which stands below it. The subject of this type evidently refers to a story related by Diogenes Laertius (viii. 2. § 11) that the Selinuntines were afflicted with a pestilence from the marshy character of the lands adjoining the neighboring river, but that this was cured by works of drainage, suggested by Empedocles. A figure standing on some coins is the river-god Selinus, which was thus made conducive to the salubrity of the city.

Sicily, Selinos. ca 450 BC. AR Tetradrachm.

ΣΕΛ-ΙΝ-ΟΝΤ-ΙΟΝ, Artemis driving quadriga left, Apollo beside her drawing bow / ΣΕΛΙΝ-ΟΣ, river god Selinos standing left holding patera & branch, sacrificing over altar; cock left, selinon leaf & bull standing on pedestal right

Sicily, Selinos AR Tetradrachm. Circa 460-440 BC

ΝΟ-ΙΤΝ-ΟΝΙΛΕΣ (retrograde), Artemis driving slow quadriga left, holding reins in both hands; beside her, Apollo standing left, drawing bow

Nude ΣΕΛΙΝΟΣ walking left, holding in right hand a phiale over canopied altar, palm branch in left; to left, rooster standing left before altar; to right, selinon leaf & bull standing left on basis

Sicily, Selinos. Circa 450-440 BC. AR Tetradrachm.

Artemis driving quadriga left; Apollo stands left beside her, drawing bow / Selinos walking left, holding branch & phiale over canopied altar; rooster on altar, bull on basis & selinon leaf to right

Sicily, Selinos. Circa 450-440 BC. AR Tetradrachm.

Artemis driving quadriga left; Apollo stands left beside her, drawing bow / Selinos walking left, holding branch & phiale over canopied altar; rooster on altar, bull on basis & selinon leaf to right

La monetazione selinuntina comincia nel VI sec. aC: la città appartiene all’area del didramma (Selinunte, Agrigento, Gela e Camarina), moneta greca d'argento del valore di due dramme, detta talora anche statere, e di peso vario secondo il sistema monetario in cui era battuta.

Le monete

presentano al dritto il parásëmon, l'emblema, della città: la foglia

dell’apio selvatico (sélinon) con almeno tre lobi, al rovescio un

quadrato incuso (in incavo anziché in rilievo), successivamente sostituito

dalla foglia di sélinon.

Le emissioni monetali di Selinunte possono essere suddivise cronologicamente

secondo questi criteri: grandezza del tondello; grandezza della foglia di sélinon;

comparsa dei globetti (dapprima due poi quattro) indicanti il valore della

moneta; comparsa della foglia di sélinon sul rovescio dentro il

quadrato incuso; comparsa della leggenda SELI sulle monete.

Per quanto concerne il sistema metrologico è evidente in Selinunte l’utilizzo del sistema euboico-attico; questo tipo di monetazione adoperato dalla colonia megarese è stato riscontrato anche ad Agrigento, Erice, Segesta, Palermo, Gela e Camarina.

Il nominale del sistema monetario selinuntino è il didramma con un peso variabile tra 9,40 e 6,60 gr, seguito dall’obolo (da 0,77 a 0,31 gr) caratterizzato sul dritto e sul rovescio dalla foglia di apio e da un altro valore simile all’obolo nel peso ma contraddistinto dal sélinon sul dritto e da un bocciolo di rosa sul rovescio; infine c’è anche un sesto di litra (da 0,13 a 0,06 gr) connotato dalla foglia di apio sul dritto e da due globetti sul rovescio. Per quanto concerne la cronologia delle emissioni monetali selinuntine di epoca arcaica queste sembrano occupare un arco cronologico compreso tra il 540 e il 470 aC.

Quanto alla foglia di sélinon, essa costituisce una presenza costante nella monetazione di Selinunte. Tale simbolo è stato interpretato da alcuni studiosi come un emblema parlante della città senza alcuna valenza; tuttavia l’analisi di taluni documenti numismatici mostra come l’uso del sélinon e di altre foglie in genere sia strettamente collegato, sulla moneta, al culto di alcune divinità maschili. In Sicilia, ad esempio, foglie molto simili all’apio compaiono su alcune monete secondarie di Akragas e Katane. Sulle prime la foglia appare in connessione con un granchio, animale riconducibile ai culti Heliaci; mentre sulle seconde si accompagna alla testa di Apollo. Questi dati hanno trovato confronto anche in alcune emissioni provenienti dalla Grecia, in particolare nella monetazione di Camiro a Rodi, isola in cui era preminente il culto di Apollo e a Melo dove in alcune monete di V sec. aC compare una foglia trilobata (forse una foglia di fico) associata a un fiore astraliforme.

La connessione tra il culto apollineo e il sélinon trova riscontro anche nelle fonti letterarie; infatti scrive Plutarco che i selinuntini consacrarono un ramo d’oro di sélinon al dio del fico (Apollo).

L’apio

era associato anche a Dioniso nel cui culto era contemplato l’uso di una

corona fatta di questa pianta (Teocrito, Idillio III, 23) e a Eracle

che fu il primo a cingersi la fronte con una corona di sélinon come

vincitore; inoltre durante i giochi istmici, per lungo tempo, i serti dati ai

vincitori erano fatti con questa pianta.

L’apio tuttavia ebbe anche una valenza sepolcrale. Infatti, scrive Plutarco,

era usanza diffusa cingervi le steli funerarie. Quest’ultimo dato trova

rimando in un pinax - quadretto votivo in terracotta - locrese raffigurante

Ade e Persefone seduti in trono: il dio degli inferi tiene in mano una pianta

di sélinon, la sua compagna regge tra le mani un gallo e delle spighe.

Uno

dei pínakes![]() dalla numerosissima collezione di Locri

dalla numerosissima collezione di Locri

conservata presso il Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia di Reggio Calabria

raffigura Persefone![]() e

Ades

e

Ades![]() seduti

sul trono - V secolo aC.

seduti

sul trono - V secolo aC.

Secondo Porfirio![]() il gallo era sacro a Persefone

il gallo era sacro a Persefone

che ne regge uno nella mano destra.

A conferma di quanto sostenuto finora ci sono anche delle dracme selinuntine di V sec. aC che recano sul dritto una testa femminile accompagnata dalla leggenda EURUMEDO. Questo termine è composto da due parole: EURUS, spesso usato nei composti per indicare qualcosa di particolarmente grande, e dal verbo MEDO che significa regnare: quindi la leggenda monetale indicherebbe una divinità femminile “colei che regna grandemente” la quale etimologicamente potrebbe essere associata a quella “Pasicrateia” menzionata nell’iscrizione del tempio G e che alcuni studiosi hanno identificato come Persefone.

Sicily,

Selinos. c 420-410 BC. AR Litra.

Nymph seated left on rock holding serpent which she feeds from her breast

Man-headed bull standing right; selinon leaf above

Ancora degne di nota sono delle litre (antica moneta d'argento dalla quale derivò la libbra romana, pari a 1/10 del didramma e del peso di.0,87 g) selinuntine recanti sul dritto una figura femminile che accarezza un serpente e sul retro un toro col volto umano: alcuni studiosi hanno riconosciuto in queste monete Persefone sedotta da Zeus sotto forma di serpente. L’associazione di queste due divinità trova espressione, nella colonia megarese, nel celebre santuario di Demetra Malophoros dove al culto della divinità femminile era associato anche quello di Zeus Meilichios.

Il tipo monetale selinuntino - dice la Carrè - rispecchierebbe così le molteplici caratteristiche di un dio che trova nella foglia di sélinon la sua più antica epifania arborea.

Dopo questa breve digressione sulla numismatica selinuntina possiamo ora considerare il ripostiglio di monete d’argento trovato a Selinunte nel 1985. Il deposito è costituito da 165 monete, 4 lingotti frammentari e un piccolo gettone ed è il più antico di tutta la Sicilia.

Le monete sono tutte di periodo arcaico e rappresentano otto diverse zecche. Il tesoretto contiene: due esemplari di terzo di statere provenienti da Metaponto, contraddistinti sul dritto da una spiga d’orzo con foglie alla base, cerchio di perline e la leggenda MET; sul rovescio è la stessa spiga fatta ad incuso (cioè impressa sulla superficie); un esemplare di dracma proveniente da Poseidonia. La moneta reca a dritto le leggende FIIS e POSEI e Poseidone che avanza con la clamide sulle spalle e brandendo un tridente nella mano destra. Sul rovescio vi sono le medesime leggende presenti sul dritto fatte a rilievo, la figura del dritto fatta a incuso e un cerchio con linee a raggiera in rilievo; tre terzi di stateri provenienti da Sibari recanti sul dritto la leggenda SU (Sibari) e un toro stante con testa retrospicente. Sul rovescio una dracma da Himera che presenta sul dritto un gallo stante e un cerchio di perline. Al rovescio un quadrato incuso suddiviso in 4 triangoli in rilievo e 4 incavati circondato da un bordo striato; trentacinque didrammi di Selinunte recanti sul dritto la foglia del sélinon e sul rovescio un quadrato incuso diviso in 10, 12 o 8 triangoli databili tra 540 e 510 aC. Il numero delle monete selinuntine costituisce meno di un quarto dell’intero deposito. Questa proporzione relativamente bassa di monete locali in un tesoretto siciliano è un evento eccezionale; infatti i depositi monetali trovati nell’isola e ascrivibili all’epoca arcaica sono in genere costituiti esclusivamente da monete coniate in Sicilia. Il quadro della circolazione in relazione all’epoca in questione indica inoltre che le monete coniate nella parte occidentale dell’isola non penetrarono in quella orientale e viceversa. È anche rilevante il fatto che nel tesoretto di Selinunte sono presenti monete magnogreche, dato eccezionale ma facilmente interpretabile considerando la grande attività commerciale intrapresa dalla colonia megarese.

Le monete selinuntine hanno un peso variabile tra 7,65 e 9,23 gr e si tratta verosimilmente di didrammi. Alcune di queste monete recano delle particolarità: in una la foglia del sélinon si è trasformata in una testa animale, forse una volpe o un pipistrello; in altre si è osservato che la foglia dell’apio è piccola, trilobata e posta su tondelli più spessi: si tratta di esemplari più antichi; in due esemplari invece la foglia del sélinon è resa più realisticamente. sono emissioni più recenti e provengono dalla stessa coppia di coni.

Nel tesoretto sono altresì presenti delle monete greche e precisamente: un tetradramma proveniente da Abdera recante sul dritto un grifo seduto e sul rovescio un quadrato incuso diviso in 4 scomparti; sei esemplari di stateri egineti databili tra 535 e 520 aC; recanti sul dritto una tartaruga marina con fila di globetti sul dorso e sul rovescio un quadrato incuso con disegno non sviluppato; settantuno stateri egineti, una emidracma e una dracma databili tra 525 e 500 aC, recanti sul dritto lo stesso emblema della serie precedente. Le particolarità di queste ultime monete sono nei particolari che nel secondo gruppo sono resi in maniera più dettagliata e nel rovescio dove compare un quadrato incuso con 8 triangoli incavati..Due stateri egineti, databili tra 510 e 490 aC, hanno sul dritto la tartaruga e sul rovescio un quadrato incuso con 5 sezioni incavate.

Le 81 monete eginetiche trovate nel tesoretto di Selinunte appartengono tutte alla seconda metà del VI sec. aC. Rilevante è il fatto che queste monete raramente vengono tesaurizzate nel Mediterraneo occidentale: oltre a Selinunte: Solo un deposito trovato a Taranto ha restituito una percentuale analoga: tre dracme corinzie databili tra 560 e 500 aC, recanti sul dritto Pegaso e sul retro pale di mulino incuse; dodici stateri corinzi databili tra 560 e 500 aC con svastica incusa sul rovescio; uno statere corinzio dello stesso periodo delle due serie precedenti con quadrato incuso quadripartito a rovescio; 23 stateri corinzi databili tra 515 e 475 aC recanti una piccola testa di Athena in un quadrato incuso.

Nel tesoretto erano altresì presente dell’argento non coniato, un gettone del peso di 2,45 gr in argento, inciso con uno scalpello, frammenti di lingotti rettangolari di cui il primo del peso di 303,6 gr graffito; il secondo del peso di 160,3 gr recante su un lato un marchio raffigurante una tartaruga e il terzo del peso di 597,4 gr marchiato con uno stampo riproducente una testa maschile barbata; un lingotto a forma di focaccia inciso con scalpello del peso di 420,7 gr contrassegnato con il simbolo del quadrato incuso.

L’importanza dl deposito selinuntino è straordinaria. Infatti esso costituisce l’unica testimonianza per datare l’ingresso in Sicilia di monete arcaiche provenienti dalla Grecia e dalla Magna Grecia.

Il

tesoretto di Selinunte

di Giuseppe Stabile

www.arkeomania.com

Selinon leaf - Incuse square irregularly divided

Selinus (Selinoûs-oûntos), the most western of all the Greek cities of Sicily, stood near the mouth of the river Selinus and a few miles west of that of the Hypsas, called Belice today. It derived its name from the river, which in its turn was called after the sélinon (probably the wild celery, Apium graveolens), which grew plentifully on its banks. The Selinuntines adopted from the first the leaf of this plant as the badge of their town (Plut. Pyth. Orac. xii), placing it upon their coins, and dedicating, on one occasion, a representation of it in gold in the temple of Apollo at Delphi (Plut. l. c.).

In the great Carthaginian invasion of Sicily in BC 480, Selinus appears to have sided with the invaders (Diod. xi. 21). During the period of general prosperity which followed the expulsion of the tyrants, BC 466, it rose to considerable power and wealth (Thuc. vi. 20). It must have been quite early in this period of peace that it was attacked by a devastating pestilence or malaria, caused by the stagnant waters in the neighbouring marsh lands (Diog. Laert. viii. 2.70). On that occasion the citizens had recourse to the arts of Empedocles, then at the height of his fame. The philosopher put a stop to the plague, it would seem, by connecting the channels of two neighbouring streams (Diog. Laert. l. c.). In gratitude for this deliverance the Selinuntines conferred upon him divine honours, and their coin-types still bear witness to the depth and lasting character of the impression which the purification of the district made upon men’s minds. The coins of this period are as follows.

ΣΕΛΙΝΟΝΤΙΟΝ Apollo and Artemis standing side by side in slow quadriga, the former discharging arrows from his bow

ΣΕΛΙΝΟΣ The river-god Selinos naked, with short horns, holding phiale and lustral branch, sacrificing at an altar of Apollo (?) the healer, in front of which is a cock. Behind him on a pedestal is the figure of a bull, and in the field above a selinon leaf.

Apollo, who on one specimen (Imhoof, Mon. gr., p. 28) appears alone, is here regarded as the healing god who, with his radiant arrows, slays the pestilence as he slew the Python. Artemis stands behind him in her capacity of delivery, for the plague had fallen heavily on the women too (Diog. Laert. l. c.). On the reverse the river-god himself makes formal libation to the healer-god in gratitude for the cleansing of his waters, while the image of the bull, being sometimes man-headed, perhaps represents the river in its former aspect as an untamed natural force.

ΣΕΛΙΝΟΝΤΙΟΝ Herakles contending with a wild bull which he seizes by the horn, and is about to slay with his club.

ΗΥΨΑΣ River Hypsas sacrificing before altar, around which a serpent twines. He holds branch and phiale. Behind him a marsh-bird is seen departing. In field, selinon leaf.

Here instead of Apollo it is the sun-god Herakles, who is shown struggling with the destructive powers of water symbolized by the bull, while on the reverse the Hypsas takes the place of the Selinos. Perhaps the marsh-bird is retreating, because she can no longer find a congenial home on the banks of the Hypsas now that Empedocles has drained the lands.

www.snible.org