Lessico

Segale

Secale cereale

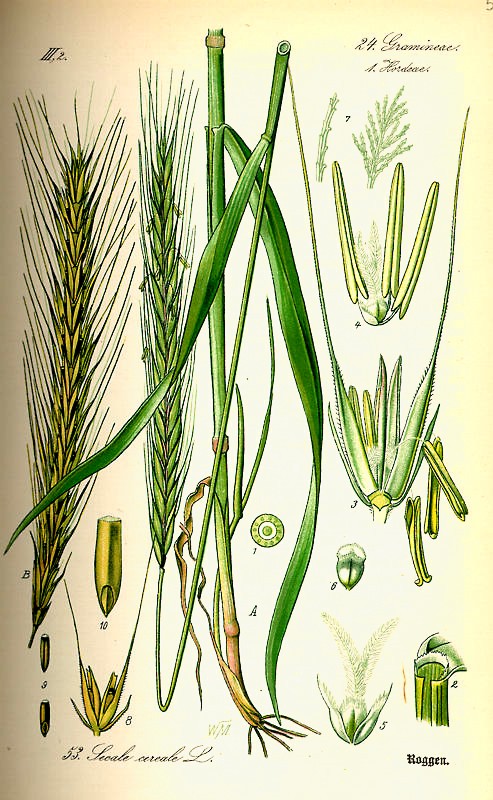

Pianta della famiglia Graminacee originaria dell'Asia sud-occidentale, dove vive una varietà spontanea, e attualmente coltivata su larga scala in vari Paesi dell'Europa settentrionale, d'Asia e d'America dove per la rigidità del clima il frumento non prospera.

È un

cereale simile al frumento![]() , ma più

sviluppato di questo (è alto fino a 2 m), con foglie di colore quasi glauco e

spiga allungata, un po' pendula, nella quale ciascuna spighetta matura due

cariossidi, con glumelle esterne che terminano in reste aculeate e rigide. Le

cariossidi sono nude, più lunghe e sottili di quelle del frumento, appuntite

alla base e foggiate a calotta all'estremità opposta, di colore variabile dal

grigio-verde al bruno scuro secondo la varietà. In Italia la segale è

coltivata su scala ridotta, specialmente in località montane o di alte

colline, per lo più nelle regioni alpine.

, ma più

sviluppato di questo (è alto fino a 2 m), con foglie di colore quasi glauco e

spiga allungata, un po' pendula, nella quale ciascuna spighetta matura due

cariossidi, con glumelle esterne che terminano in reste aculeate e rigide. Le

cariossidi sono nude, più lunghe e sottili di quelle del frumento, appuntite

alla base e foggiate a calotta all'estremità opposta, di colore variabile dal

grigio-verde al bruno scuro secondo la varietà. In Italia la segale è

coltivata su scala ridotta, specialmente in località montane o di alte

colline, per lo più nelle regioni alpine.

Il cereale

è soggetto alle medesime malattie crittogamiche che affliggono il frumento.

Di particolare importanza per le gravi intossicazioni alimentari che provoca

nell'uomo e negli animali l'infezione provocata dal fungo Claviceps

purpurea (segale cornuta![]() ). Dalle

cariossidi della segale si ottiene una farina alimentare con cui si produce un

pane di più lunga conservazione, ma meno digeribile di quello di frumento; in

alcuni Paesi esse servono anche per la produzione di birra e whisky

). Dalle

cariossidi della segale si ottiene una farina alimentare con cui si produce un

pane di più lunga conservazione, ma meno digeribile di quello di frumento; in

alcuni Paesi esse servono anche per la produzione di birra e whisky![]() . Da sola

o consociata con altre piante, infine, la segale serve per fare erbai.

. Da sola

o consociata con altre piante, infine, la segale serve per fare erbai.

Segale

cornuta

Claviceps purpurea

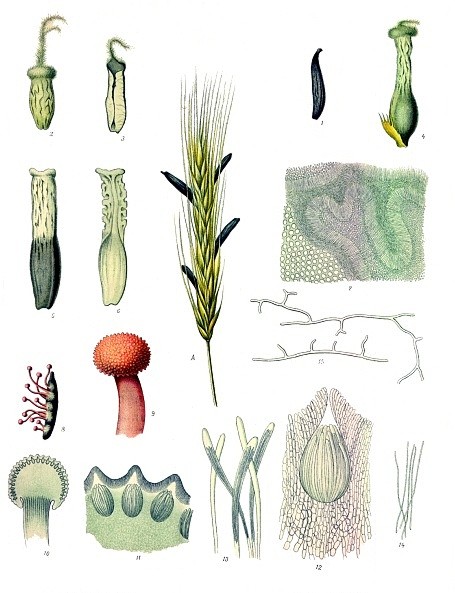

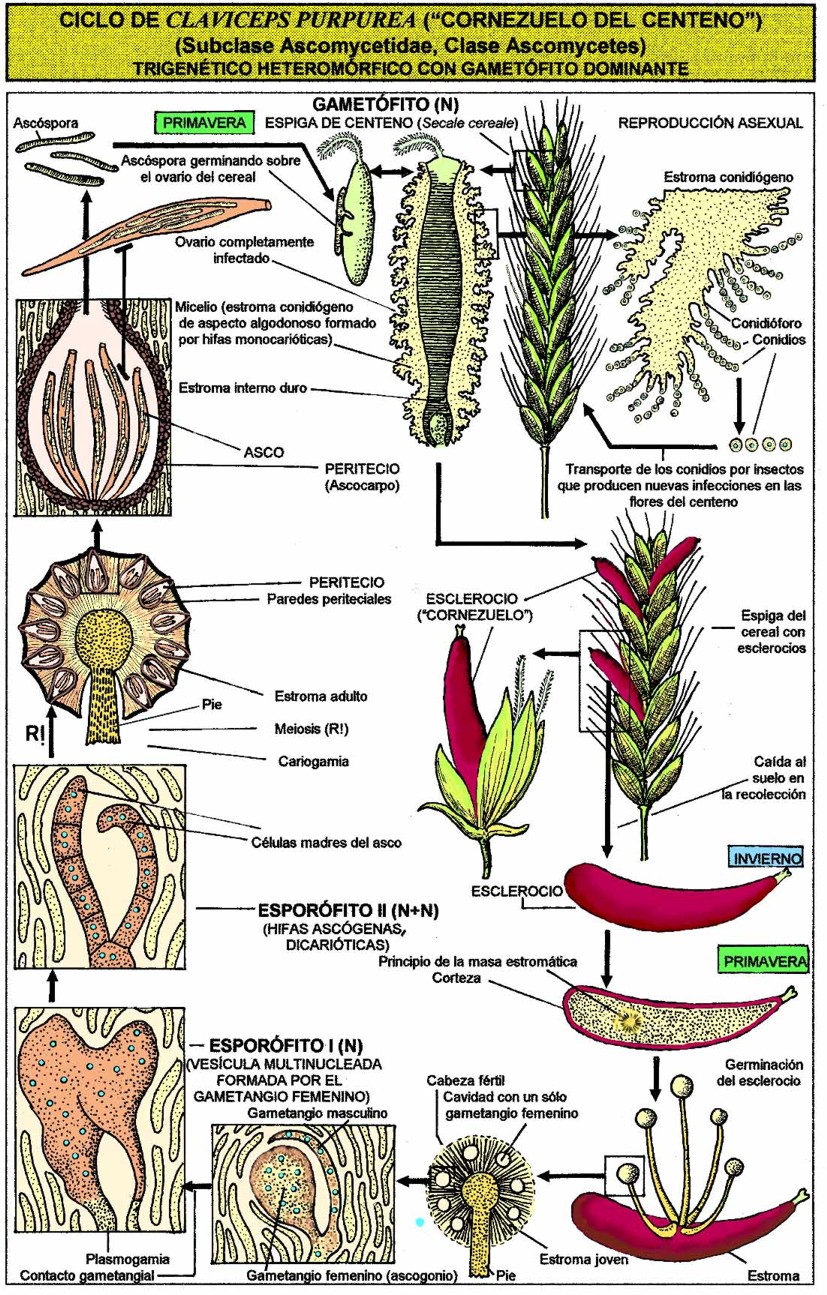

Nome di una malattia crittogamica che colpisce la segale e altri cereali, detta anche mal dello sclerozio e chiodo segalino, di cui è responsabile il fungo ascomicete Claviceps purpurea.

L'infezione ha luogo all'epoca della fioritura, quando le ascospore prodotte dal fungo, portate dal vento, si depositano sullo stimma dei fiori, dove germinano. Il micelio del fungo si sviluppa attraverso i tessuti dell'ovario, atrofizzandolo e dando luogo a voluminosi sclerozi, a forma di cornetti (da cui il nome), che si sostituiscono alle cariossidi e alla fine del periodo vegetativo del cereale cadono al suolo, dove svernano. Nella primavera successiva, dagli sclerozi si sviluppano nuove ascospore, che riprendono il ciclo.

La malattia non ha gravi conseguenze per le colture, cui provoca danni irrilevanti, ma l'ingestione degli sclerozi assieme al cereale sano è causa di una grave intossicazione per l'uomo e gli animali (ergotismo). Gli sclerozi sono infatti alcaloidi con effetti allucinogeni e fortemente tossici, i principali dei quali sono l'ergotomina, l'ergonovina, l'ergocristina, l'ergocriptina, l'ergocornina. Gli estratti totali di segale, o i singoli alcaloidi, vengono largamente usati in medicina, e in particolare in ostetricia per la loro energica azione contratturante sull'utero.

L'azione allucinogena degli alcaloidi diviene molto più intensa sottoponendo la molecola degli alcaloidi naturali ad azione chimica, depurante le fasi tossiche, come quella che li trasforma nella dietilammide dell'acido lisergico, indicata con la sigla LSD.

Il nome

deriva dal francese ergot che significa sperone, verosimilmente perché

gli sclerozi della Claviceps purpurea somigliano allo sperone del gallo. Nei

secoli passati questa sindrome era detta Fuoco di Sant'Antonio![]() oppure di

San Marziale

oppure di

San Marziale![]() , oppure

di San Martino

, oppure

di San Martino![]() , ma

non ha nulla a che vedere con quello attuale di origine virale o herpes zoster

, ma

non ha nulla a che vedere con quello attuale di origine virale o herpes zoster![]() .

L'ergotismo era spesso etichettato come fuoco persiano

.

L'ergotismo era spesso etichettato come fuoco persiano![]() . Il

nome di fuoco di Sant'Antonio è dovuto al fatto che i monaci dell'Ordine di

Sant'Antonio si erano specializzati nel trattamento delle vittime

dell'ergotismo ed erano anche in grado di procedere alle amputazioni degli

arti in caso di gangrena.

. Il

nome di fuoco di Sant'Antonio è dovuto al fatto che i monaci dell'Ordine di

Sant'Antonio si erano specializzati nel trattamento delle vittime

dell'ergotismo ed erano anche in grado di procedere alle amputazioni degli

arti in caso di gangrena.

L'ergotismo è un'intossicazione cronica di origine alimentare provocata da farine di cereali contenenti gli sclerozi della segale cornuta. Ne sono note due diverse forme cliniche: una gangrenosa e una convulsiva.

La prima è caratterizzata da disturbi della circolazione periferica e da dolori agli arti che, nei casi gravi, precedono la gangrena; la seconda è rappresentata da vertigini, crampi dolorosi agli arti, contratture muscolari e crisi convulsive. Attualmente l'ergotismo è molto raro, soprattutto per i miglioramenti apportati alla molitura dei cereali.

Rye (Secale cereale) is a grass grown extensively as a grain and forage crop. It is a member of the wheat tribe (Triticeae) and is closely related to barley and wheat. Rye grain is used for flour, rye bread, rye beer, some whiskies, some vodkas, and animal fodder. It can also be eaten whole, either as boiled rye berries, or by being rolled, similar to rolled oats.

Rye is a cereal and should not be confused with Ryegrass which is used for lawns, pasture, and hay for livestock.

History

The early history of rye is unclear. The wild ancestor of rye has not been identified with certainty, but is one of a number of species that grow wild in central and eastern Turkey, and adjacent areas. Domesticated rye occurs in small quantities at a number of Neolithic sites in Turkey, such as PPNB Can Hasan III, but is otherwise virtually absent from the archaeological record until the Bronze Age of central Europe, c. 1800-1500 BC. It is possible that rye travelled west from Turkey as a minor admixture in wheat, and was only later cultivated in its own right. Although archeological evidence of this grain have been found in Roman contexts along the Rhine Danube and in the British Isles, Pliny the Elder is dismissive of rye, writing that it "is a very poor food and only serves to avert starvation" and wheat is mixed into it "to mitigate its bitter taste, and even then is most unpleasant to the stomach" (N.H. 18.140-141: Et silicia, hoc est fenum Graecum, scariphatione seritur, non altiore quattuor digitorum sulco, quantoque peius tractatur, tanto provenit melius. rarum dictu esse aliquid, cui prosit neglegentia. id autem, quod secale ac farrago appellatur, occari tantum desiderat. 141 Secale Tauri sub Alpibus asiam vocant, deterrimum et tantum ad arcendam famem, fecunda, sed gracili stipula, nigritia triste, pondere praecipuum. admiscetur huic far, ut mitiget amaritudinem eius, et tamen sic quoque ingratissimum ventri est. nascitur qualicumque solo cum centesimo grano, ipsumque pro laetamine est.)

Since the Middle Ages, rye has been widely cultivated in Central and Eastern Europe and is the main bread cereal in most areas east of the French-German border and north of Hungary.

Claims of much earlier cultivation of rye, at the Epipalaeolithic site of Tell Abu Hureyra in the Euphrates valley of northern Syria, remain controversial. Critics point to inconsistencies in the radiocarbon dates, and identifications based solely on grain, rather than on chaff.

Agronomy

Rye, alone or overseeded,

is planted as a livestock forage or harvested for hay. It is highly tolerant

of soil acidity and is more tolerant of dry and cool conditions than wheat,

though not as tolerant of cold as barley. In Turkey, rye is often grown as an

admixture in wheat crops. It is appreciated for the flavour it brings to bread,

as well as its ability to compensate for wheat's reduced yields in hard years.

The flame moth, rustic shoulder-knot and turnip moth are among the species of

Lepidoptera whose larvae feed on rye.

Diseases

Rye is highly susceptible to the ergot fungus. Consumption of ergot-infected rye by humans and animals results in a serious medical condition known as ergotism. Ergotism can cause both physical and mental harm, including convulsions, miscarriage, necrosis of digits, and hallucinations. Historically, damp northern countries that have depended on rye as a staple crop were subject to periodic epidemics of this condition.

Uses

Rye bread, including pumpernickel, is a widely eaten food in Northern and Eastern Europe. Rye is also used to make the familiar crisp bread. Rye flour has a lower gluten content than wheat flour, and contains a higher proportion of soluble fiber.

Some other uses of rye include rye whiskey and use as an alternative medicine in a liquid form, known as rye extract. Often marketed as Oralmat, rye extract is a liquid obtained from rye and similar to that extracted from wheatgrass. Its benefits are said to include a strengthened immune system, increased energy levels and relief from allergies, but there is no clinical evidence for its efficacy. Rye straw is used to make corn dollies.

Ergot

Ergot on wheat

Ergot is the common name of a fungus in the genus Claviceps that is parasitic on certain grains and grasses. The form the fungus takes to winter-over is called a sclerotium, and this small structure is what is usually referred to as 'ergot', although referring to the members of the Claviceps genus as 'ergot' is also correct. There are about 50 known species of Claviceps, most of them in the tropical regions. Economically important species are Claviceps purpurea (parasitic on grasses and cereals), C. fusiformis (on pearl millet, buffel grass), C. paspali (on dallis grass), and C. africana (on sorghum). Claviceps purpurea can affect a number of cereals including rye (its most common host), triticale, wheat and barley. It affects oats only rarely.

There are three races or varieties of Claviceps purpurea, differing in their host specifity:

G1 — land grasses of

open meadows and fields;

G2 — grasses from moist, forest, and mountain habitats;

G3 (C. purpurea var. spartinae) — salt marsh grasses (Spartina,

Distichlis).

Life cycle of the fungus

An ergot kernel called a sclerotium develops when a floret of flowering grass or cereal is infected by a spore of Claviceps fungus. The infection process mimics a pollen grain growing into an ovary during fertilization. The fungus then destroys the plant ovary and attaches itself to a vascular bundle originally intended for seed nutrition. The first stage of ergot infection manifests itself as a white soft tissue (known as sphacelia) producing sugary honeydew, which often drops out of the grass florets. This honeydew contains millions of asexual spores (conidia) which are dispersed to other florets by insects. Later, the sphacelia convert into a hard dry sclerotium inside the husk of the floret. At this stage, alkaloids and lipids accumulate in the sclerotium.

Claviceps species from tropic and subtropic regions produce macro- and microconidia in their honeydew. Macroconidia differ in shape and size between the species, whereas microconidia are rather uniform, oval to globose (5x3µm). Macroconidia are able to produce secondary conidia. A germ tube emerges from a macroconidium through the surface of a honeydew drop and a secondary conidium of the oval to pearlike shape is formed to which the contents of the original macroconidium migrates. Secondary conidia form white frost-like surface on honeydew drops and are spread by wind. No such process occurs in Claviceps purpurea, Claviceps grohii, Claviceps nigricans, and Claviceps zizaniae, all from North temperate regions.

When a mature sclerotium drops to the ground, the fungus remains dormant until proper conditions trigger its fruiting phase (onset of spring, rain period, etc.). It germinates, forming one or several fruiting bodies with head and stipe, variously colored (resembling a tiny mushroom). In the head, threadlike sexual spores are formed, which are ejected simultaneously, when suitable grass hosts are flowering. Ergot infection causes a reduction in the yield and quality of grain and hay produced, and if infected grain or hay is fed to livestock it may cause a disease called ergotism.

Black and protruding sclerotia of Claviceps purpurea are well known. However, many tropical ergots have brown or greyish sclerotia, mimicking the shape of the host seed. For this reason, the infection is often overlooked.

Effects on humans and animals

The ergot sclerotium contains high concentrations (up to 2% of dry mass) of ergotamine, a complex molecule consisting of a tripeptide-derived cyclol-lactam ring connected via amide linkage to a lysergic acid (ergoline) moiety, and other alkaloids of the ergoline group that are biosynthesized by the fungus. Ergot alkaloids have a wide range of biological activities including effects on circulation and neurotransmission.

Ergotism is the name for

sometimes severe pathological syndromes affecting humans or animals that have

ingested ergot alkaloid-containing plant material, such as ergot-contaminated

grains. The common name for ergotism is "St. Anthony's![]() fire" referring to

the symptoms, such as severe burning sensations in the limbs. These are caused

by effects of ergot alkaloids on the vascular system due to vasoconstriction

of blood vessels, sometimes leading to gangrene and loss of limbs due to

severely restricted blood circulation. The neurotropic activities of the ergot

alkaloids may also cause hallucinations and attendant irrational behaviour,

convulsions, and even death. Other symptoms include strong uterine

contractions, nausea, seizures, and unconsciousness. Monks of the order of St.

Anthony the Great specialized in treating ergotism victims with balms

containing tranquilizing and blood circulation-stimulating plants; they were

also skilled in amputations.

fire" referring to

the symptoms, such as severe burning sensations in the limbs. These are caused

by effects of ergot alkaloids on the vascular system due to vasoconstriction

of blood vessels, sometimes leading to gangrene and loss of limbs due to

severely restricted blood circulation. The neurotropic activities of the ergot

alkaloids may also cause hallucinations and attendant irrational behaviour,

convulsions, and even death. Other symptoms include strong uterine

contractions, nausea, seizures, and unconsciousness. Monks of the order of St.

Anthony the Great specialized in treating ergotism victims with balms

containing tranquilizing and blood circulation-stimulating plants; they were

also skilled in amputations.

In addition to ergot alkaloids, Claviceps paspali also produces tremorgens (paspalitrem) causing "paspalum staggers" in cattle. Ergot alkaloids are also produced by fungi of the genera Penicillium and Aspergillus, notably by some isolates of the human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus, and have been isolated from plants in the family Convolvulaceae, of which morning glory is best known.

Historically, controlled doses of ergot were used to induce abortions and to stop maternal bleeding after childbirth, but simple ergot extract is no longer used as a pharmaceutical. Ergot contains no lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) but instead contains ergotamine which is used to synthesize lysergic acid which is then used for lysergic acid diethylamide synthesis. Moreover, lysergic acid, a molecule used in the synthesis of LSD, can be isolated from ergot.

In the January 4, 2007 edition of the New England Journal of Medicine, a paper was published documenting a British study of over 11,000 Parkinson's Disease patients, which found that two commonly used Parkinson's drugs derived from ergot, Pergolide and Cabergoline, may increase the risk of leaky heart valves by up to 700%.

Speculations

The disease cycle of the ergot fungus was first described in the 1800s, but the connection with ergot and epidemics among people and animals was known several hundred years before that.

Human poisoning due to the consumption of rye bread made from ergot-infected grain was common in Europe in the Middle Ages. The epidemic was known as St. Anthony's Fire or ignis sacer.

It has also been posited — though speculatively — that the Salem Witch Trials were initiated by young women who had consumed ergot-tainted rye. The Great Fear in France during the Revolution has also been linked by some historians to the influence of ergot.

British author John Grigsby claims that the presence of ergot in the stomachs of some of the so called 'bog-bodies' - Iron Age human remains from peat bogs N E Europe such as Tollund man - reveals that ergot was once a ritual drink in a prehistoric fertility cult akin to that at Eleusis in Greece. In his book Beowulf and Grendel he argues that the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf is based on a memory of the quelling of this fertility cult by followers of Odin. He states that Beowulf, meaning barley-wolf, suggests a connection to ergot which in German was known as the 'tooth of the wolf'.

Poisonings due to consumption of seeds treated with mercury compounds are sometimes misidentified as ergotism, such as the case of mass-poisoning in the French village Pont-Saint-Esprit in 1951:

The mass poisoning which took place in the French town of Pont-St. Esprit in 1951 has been widely presented in the lay and scientific press as an example of ergotism. While the poisoning was traced to bread, ergotism was not the cause of the syndrome, which was due to a toxic mercury compound used to disinfect grain to be planted as seed. Some sacks of grain treated with the fungicide were inadvertently ground into flour and baked into bread. Albert Hofmann arrived at this conclusion after visiting Pont-St. Esprit, and analyzing samples of the bread (which contained no ergot alkaloids) and autopsy samples of four of the victims who succumbed (Hofmann 1980; Hofmann 1991). On the other hand, Swedish toxicologist Bo Holmstedt insists the poisoning was in fact due to ergotism (Holmstedt 1978).

As Dr. Simon Cotton (member of the Chemistry Department of Uppingham School, U.K.) notes, there have been numerous cases of mass-poisoning due to consumption of mercury-treated seeds:

More horrifying than this were epidemics of poisoning, caused by people eating treated seed grains. There was a serious epidemic in Iraq in 1956 and again in 1960, whilst use of seed wheat (which had been treated with a mixture of C2H5HgCl and C6H5HgOCOCH3) for food, caused the poisoning of about 100 people in West Pakistan in 1961. Another outbreak happened in Guatemala in 1965. Most serious was the disaster in Iraq in 1971–2, when according to official figures 459 died. Grain had been treated with methyl mercury compounds as a fungicide and should have been planted. Instead it was sold for milling and made into bread. It had been dyed red as a warning and also had warning labels in English and Spanish that no one could understand.

Kykeon, the beverage consumed by participants in the ancient Greek mystery of Eleusinian Mysteries, might have been based on hallucinogens from ergot.

Currently, rye grain is infected repeatedly to produce ergot.

Ergot and Its Alkaloids

Paul

L. Schiff, Jr., PhD

School of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh

Corresponding Author: Paul L. Schiff, Jr, PhD. Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15261. Tel: 412-648-8462. Fax: 412-383-7436. E-mail: pschiff@pitt.edu

Received January 10, 2006; Accepted April 4, 2006.

Abstract

This manuscript reviews the history and pharmacognosy of ergot, and describes the isolation/preparation, chemistry, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacotherapeutics of the major ergot alkaloids and their derivatives. A brief discussion of the hallucinogenic properties of lysergic acid diethylamide is also featured. An abbreviated form of the material found in this paper is presented in a 4-hour didactic format to third-professional year PharmD students as part of their study of vascular migraine headaches, Parkinson's disease, and naturally occurring hallucinogens/hallucinogen derivatives in the modular course offering Neurology/Psychiatry.

Keywords: ergot, ergotism, ergot alkaloids, ergot alkaloid derivatives

HISTORY OF ERGOT

Students at the University of Pittsburgh receive an introduction to pharmacognosy and natural products during their first-professional year in an introductory course in Drug Development. The role of natural products as both historical and continuing sources of drugs, as well as sources of precursors for semisynthetic modification and sources of probes for yet undiscovered drug moieties, is emphasized. In addition, students are continually exposed to the concept that complex natural products are a result of secondary metabolism, and as such are produced via the unique combination of a relatively limited number of structurally unsophisticated primary metabolites. As a consequence, secondary metabolites have a more limited distribution in nature, and their occurrence is an expression of the individuality of the parent species. This curricular dialog with pharmacognosy and various bioactive natural products continues in courses in the second-professional year (Pharmacotherapy of Infectious Disease 1 and 2 Cardiology) and third-professional year (Oncology, Pulmonology & Rheumatology, Neurology/Psychiatry).

Early History

Although it has been speculated that the 4,000-year old Eleusinian Mysteries of ancient Greece were connected with ergot-induced hallucinations, the earliest authenticated reports of the effects of ergot occurred in Chinese writings in approximately 1100 BC, when the substance was used in obstetrics. A magic spell found in a small temple in Mesopotamia dating to 1900-1700 BC referred to abnormally infested grain as mehru, while Sumerian clay tablets of the same period described the reddening of damp grain as samona. The Assyrians of this era were sufficiently knowledgeable to differentiate between different diseases affecting grain and by 600 BC writings on an Assyrian tablet alluded to a “noxious pustule in the ear of grain.” References to grain diseases have also been found in various books of the Bible in the Old Testament (850-550 BC). In 550 BC the Hearst Papyrus of Egypt described a particular preparation in which a mixture of ergot, oil, and honey was recommended as a treatment for hair growth. In 370 BC Hippocrates furnished a description of corn blight and subsequently described ergot as melanthion, noting its use to halt postpartum hemorrhage. Around 350 BC the Parsi wrote of “noxious grasses that cause pregnant women to drop the womb and die in childbed,” while in 322 BC Aristotle postulated that grain rust was caused by warm vapors. Around 286 BC the Greeks concluded that barley was more susceptible than wheat to rust infections, and that windy fields had less rust than damp, shady low-lying ones.

Middle Ages to Twentieth Century

The first documented epidemic of ergotism likely occurred in 944-945 AD, when some 20,000 people of the Aquitane region of France (about half of the population) died of the effects of ergot poisoning. Some 50 years later, about 40,000 people reportedly died because of the “holy fire.”

Up through the 18th Century botanists persisted in considering ergot to be a “super” rye, possessing an enlarged kernel. Finally, in 1764, ergot was recognized as a fungus by von Munchhausen. Epidemics of ergot poisoning, often termed ergotism, continued to ravage continental Europe through the Middle Ages and outbreaks of ergotism occurred in Germany in 1581, 1587, and 1596. These epidemics were due, in part, to the fact that rye was grown in larger quantities in medieval times, and many people (particularly those less wealthy) ingested contaminated rye flour.

These outbreaks were characterized by the production of 2 distinct forms of toxic reactions, with these reactions now being understood to be attributable to the effects of the alkaloids produced by the parasitic ergot fungus which was contained within the ergot fungal body (sclerotium). The fungus-contaminated grain crops along with their fungal metabolites (ergot alkaloids) were ingested with flour prepared from the grain. The first gangrenous form (Ergotismus gangraenosus), commonly known as “holy fire,” “infernal fire,” or “St. Anthony's Fire,” was more common in France and its effects were characterized by pronounced peripheral vasoconstriction of the extremities (limbs). Hands, feet, and whole limbs would swell, producing a violent, burning pain that ultimately culminated in the separation of a dry gangrenous limb (usually a foot) at a joint, without pain or loss of blood. St. Anthony's Fire was so named because the Order of St. Anthony traditionally cared for sufferers in the Middle Ages, and the condition was characterized by severe burning pain (“fire”). The second form of ergotism, also known as the convulsive form (Ergotismus convulsivus), was particularly common in Germany and was typically characterized by the development of delirium and hallucinations, accompanied by rigid, extremely painful flexed limbs, muscle spasms, convulsions, and severe diarrhea.

The

term ignis sacer (holy fire) was commonly employed for epidemics of

ergotism, but numerous other terms, mainly of Latin derivation, were coined,

including: Ignis judicalis, Ignis occultus, Morbus hic tabificus, Mortifer

ardor, Pestilens ille morbus, Pestis ignaria, Plaga ignis, Plaga illa, and

Plaga invisibilis. Many were quite naturally translated into various

European languages, including French (Feu sacré) and German (heilige Feuer).

Other terms for ergotism included names of regions (Mal de Cologne) and of

saints to whom an appeal for help was made (St. Anthony![]() , St.

Martin

, St.

Martin![]() , St.

Martial

, St.

Martial![]() ).

).

In 1597 scientists at Marburg University observed that signs of ergotism often appeared after blighted rye grains were consumed, and that blight was promoted by cold, damp growing seasons. In 1630 it was observed that feeding of blighted grain to animals produced an illness similar to human ergotism and by the end of the 18th century poisoning was demonstrated in animals. Although the source of ergotism was linked to the consumption of infected rye by 1676, it was the large outbreaks of ergotism in Europe in 1770 and 1777 that prompted the introduction of legislation in France and elsewhere. Epidemics of gangrenous ergotism were recorded from the Middle Ages to the nineteenth century, while that of convulsive ergotism were documented between 1581 and 1928.

Twentieth Century

From 1926 to 1927, some 11,319 cases of ergotism were reported in a population of 506,000 in the vicinity of Sarapol, near the Ural mountains. In 1928, 200 Jewish refugees in Manchester, England, were sickened when they consumed rye bread that had been prepared from rye grown in South Yorkshire. In mid-August of 1951, 230 villagers of the popular French tourist town of Pont Saint-Esprit on the Rhone River were sickened after ingesting contaminated goods from a local baker. They became violently ill with symptoms of severe gastrointestinal upset, dramatic reduction in body temperature, hallucinations, euphoria, and suicidal ideation. Within days, some became extremely delirious and others complained of excruciating burning pains in the extremities, culminating in the development of gangrene in some patients.

Early Medicinal Uses

In 1582

a preparation of ergot that was employed in small doses by midwives to produce

strong uterine contractions was described by Adam Lonitzer![]() in his Kreuterbuch. The use of ergot as an oxytocic in childbirth

became very popular in France, Germany, and the United States. The first use

of the drug in official medicine was described by the American physician John

Stearns in 1808, when he reported on the uterine contractile actions of a

preparation of ergot obtained from blackened granary rye as a remedy for

“quickening childbirth.” However, shortly thereafter the number of

stillborn neonates rose to a point that the Medical Society of New York

initiated an investigation. As a result of this enquiry, it was recommended in

1824 that ergot only be used in the control of postpartum hemorrhage. Ergot

was introduced into the first edition of the United States Pharmacopeia in

1820 and into the London Pharmacopeia in 1836.

in his Kreuterbuch. The use of ergot as an oxytocic in childbirth

became very popular in France, Germany, and the United States. The first use

of the drug in official medicine was described by the American physician John

Stearns in 1808, when he reported on the uterine contractile actions of a

preparation of ergot obtained from blackened granary rye as a remedy for

“quickening childbirth.” However, shortly thereafter the number of

stillborn neonates rose to a point that the Medical Society of New York

initiated an investigation. As a result of this enquiry, it was recommended in

1824 that ergot only be used in the control of postpartum hemorrhage. Ergot

was introduced into the first edition of the United States Pharmacopeia in

1820 and into the London Pharmacopeia in 1836.

Livestock Poisoning

Ergot alkaloid contamination of livestock feeds has long been known and has been described in various places. Although reports of ergotism in livestock vary from year-to-year in the United States according to rainfall and temperature, this mycotoxicosis occurs in the grain-producing areas of the Northern plains in most years. Three syndromes have been described in animals: nervous ergotism, gangrenous ergotism, and agalactia.

REFERENCES

1.Swan,

GA. An Introduction to the Alkaloids. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc;

1967. pp. 209–215.

2.Cordell, GA. Introduction to Alkaloids. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons;

1981. pp. 622–655.

3.Trease, GE.; Evans, WC. Pharmacognosy. 12th ed. London, England: Bailliere

Tindall; 1983. pp. 599–605.

4.Rehácek, Z.; Sajdl, P. Ergot Alkaloids. New York, NY: Elsevier Science

Publishing Company; 1990. pp. 28–86.

5.Bruneton, J. Pharmacognosy, Phytochemistry, Medicinal Plants, Paris, France:

Technique & Documentation, Lavoisier; 1995. pp. 797–814.

6.Robbers, JE.;Speedie, MK.; Tyler, VE. Pharmacognosy and

Pharmacobiotechnology. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. pp.

172–7.

7.Gröger, D.; Floss, HG. Biochemistry of Ergot Alkaloids: Achievements and

Challenges. In: Cordell GA. , editor. The Alkaloids. Vol. 50. San Diego, Calif:

Academic Press, Inc; 1998. pp. 172–218.

8.Wink, M. A short history of alkaloids. In: Roberts MF, Wink M. , editors.

Alkaloids. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 11–44.

9.Dewick, PM. Medicinal Natural Products. 2nd ed. Chichester, West Sussex,

England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2002. pp. 368–76.

10.Hesse, M. Alkaloids. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2002. pp. 330–7.

11.Sanders-Bush, E.; Mayer, SE. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin): Receptor

Agonists and Antagonists. In: Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL. , editors. The

Pharmacologic Basis of Therapeutics. 11th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

pp. 297–315.

12.Aronson, SM. The Tapestery of Medicine. Providence, RI: Manisses

Communications Group, Inc; 1999. pp. 189–92.

13.Stoll, A.; Hofmann, A. The Ergot Alkaloids. In: Manske RHF. , editor. The

Alkaloids. Vol. VIII. New York, NY: Academic Press, Inc.; 1965. pp. 725–83.

14.Shelby, RA. Toxicology of ergot alkaloids in agriculture. In: Kren V, Cvak

L. , editors. Ergot, the Genus Claviceps. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Vol.

6. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1999. pp.

469–478.

15.Rehácek, Z.; Sajdl, P. Ergot Alkaloids. New York, NY: Elsevier Science

Publishing Company; 1990. pp. 87–124.

16.Tenberge, KB. Biology and life strategy of the ergot fungi. In: Kren V,

Cvak L. , editors. Ergot, the Genus Claviceps. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants,

Vol. 6. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1999. pp.

25–50.

17.Cvak, L. Industrial production of ergot alkaloids. In: Kren V, Cvak L. ,

editors. Ergot, the Genus Claviceps. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Vol. 6.

Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 373–409.

18.Németh, E. Parasitic production of ergot alkaloids. In: Kren V, Cvak L. ,

editors. Ergot, the Genus Claviceps. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Vol. 6.

Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 303–319.

19.Malinka, Z. Saprophytic production of ergot alkaloids. In: Kren V, Cvak L.

, editors. Ergot, the Genus Claviceps. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Vol. 6.

Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 321–371.

20.Buchta, M.; Cvak, L. Ergot alkaloids and other metabolites of the genus

claviceps. In: Kren V, Cvak L. , editors. Ergot, the Genus Claviceps.

Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Vol. 6. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood

Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 173–200.

21.Gröger, D. Alkaloids derived from tryptophan. In: Mothes K, Schütte HR,

Luckner M. , editors. Biochemistry of Alkaloids. Deerfield Beach, FL: VCH

Publishers; 1985. pp. 272–313.

22.Ninomiya, I.; Kiguchi, T. Ergot alkaloids. In: Brossi A. , editor. The

Alkaloids. Vol. 38. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 1–156.

23.Roberts, MF. Enzymology of alkaloid biosynthesis. In: Roberts MF, Wink M. ,

editors. Alkaloids. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 109–146.

24.Rehácek, Z.; Sajdl, P. Ergot Alkaloids. New York, NY: Elsevier Science

Publishing Company; 1990. pp. 124–137.

25.Keller, U. Biosynthesis of ergot alkaloidsi. In: Kren V, Cvak L. , editors.

Ergot, the Genus Claviceps. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Vol. 6. Amsterdam,

The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 95–163.

26.Stadler, PA.; Stütz, P. The ergot alkaloids. In: Manske RHF. , editor. The

Alkaloids. Vol. XV. New York, NY: Academic Press, Inc; 1975. pp. 1–36.

27.Ergonovine Maleate. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov.

Accessed November 01, 2005.

28.Katzung, BG.; Julius, DF. Histamine, serotonin, and the ergot alkaloids.

In: Katzung BG. , editor. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. 8th Ed. New York,

NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 265–88.

29.Methylergonovine Maleate. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov

Accessed November 01, 2005.

30.Methysergide Maleate. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov.

Accessed November 01, 2005.

31.King, DS.; Herndon, KC. Headache disorders. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee

GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM. , editors. Pharmacotherapy. 6th ed. New

York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 1105–21.

32.Ergotamine Tartrate. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov.

Accessed November 01, 2005.

33.Lüllmann, H.;Mohr, K.;Ziegler, A.; Bieger, D. Color Atlas of Pharmacology.

2nd ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2000. pp. 114–265.

34.Dihydroergotamine Mesylate. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov.

Accessed November 01, 2005.

35.Bromocriptine Mesylate. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov.

Accessed November 01, 2005.

36.Nelson, MV.;Berchou, RC.; LeWitt, PA. Parkinson's disease. In: DiPiro JT,

Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM. , editors. Pharmacotherapy.

6th Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 1075–1088.

37.Sheehan, AH.;Yanovski, JA.; Calis, KA. Pituitary gland disorders. In:

DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM. , editors.

Pharmacotherapy. 6th Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 1407–1423.

38.Pergolide Mesylate. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov.

Accessed November 01, 2005.

39.Dopheide, JA.;Theesen, KA.; Malkin, M. Childhood disorders. In: DiPiro JT,

Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM. , editors. Pharmacotherapy.

6th Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 1133–1145.

40.Cabergoline. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov. Accessed

November 01, 2005.

41.Ergoloid Mesylates. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov.

Accessed November 01, 2005.

42.O'Brien, C. Drug addiction and drug abuse. In: Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker

KL. , editors. The Pharmacologic Basis of Therapeutics. 11th ed. New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill; 2006. pp. 607–627.

43.Pagliaro, LA.; Pagliaro, AM. Comprehensive Guide to Drugs and Substances of

Abuse. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2004. pp. 302–337.

44.Doering, PL. Substance related disorders: overview and depressants,

stimulants, and hallucinogens. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR,

Wells BG, Posey LM. , editors. Pharmacotherapy. 6th Ed. New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 1175–1191.

45.Minghetti, A.; Crespi-Perellino, N. The History of Ergot. In: Kren V, Cvak

L. , editors. Ergot, the Genus Claviceps. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood

Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 1–24.

46.Snyder, SH. Drugs and the Brain. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company;

1986. pp. 190–5.

American

Journal of Pharmaceutical Education

www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov

L'ergot de seigle (Claviceps purpurea Tul.) est un champignon du groupe des ascomycètes, parasite du seigle (et d'autres céréales). Il contient des alcaloïdes responsable de l'ergotisme.

Description

C'est un mycélium permanent capable d'hiémation. Les grains touchés prennent une forme conique ; les sclérotes se colorent de marron clair à mauve et il en sort des glumes à la place du grain habituel.

Propriétés

Il contient des alcaloïdes polycycliques, comme l'ergométrine, l'ergocristine, l'ergocornine, l'ergocryptine et l'ergotamine, dont est tiré l'acide lysergique (dont le LSD est un dérivé synthétique).

Utilisation

Son usage par les

sages-femmes comme antalgique semble ancestral même si il n'est mentionné

dans un recueil de plantes médicinales qu'en 1582 par le docteur allemand

Adam Lonitzer![]() .

.

À partir du milieu du XIX siècle, son usage ancestral attire l'attention et les recherches visant à isoler les principes actifs commencent. En 1907, les britanniques G. Barger et F.H. Carr isolent une préparation active d'alcaloïdes qu'ils nomment ergotoxine. Mais c'est le pharmacologue H.H. Dale qui met en évidence les caractéristiques utéro-constrictive et inhibitrice sur l'adrénaline de la préparation. En 1908, un médecin américain (John Stearn) consacre une publication (Account of the pulvis parturiens, a remedy for quickening childbirth) à l'ergot qui le met en avant dans la médecine traditionnelle. Mais son usage est jugé trop dangereux pour l'enfant puisqu'en cas d'erreur de dosage la parturiente souffre de spasmes utérins; son utilisation se limite ensuite à la réduction des hémorragies postnatales. Et ça n'est qu'en 1918 qu'Arthur Stoll isole enfin un alcaloïde, l'ergotamine ce qui ouvre la voie à l'usage thérapeutique. Finalement dans les années 1930, les américains W.A. Jacob et L.C. Craig isole l'élément fondamental commun à tous les alcaloïdes de l'ergot, l'acide lysergique. Enfin, Arthur Stoll et E. Burckhardt isolent le principe anti-hémorragique de l'ergot, l'ergométrine (aussi appelée ergobasine ou ergonovine). Albert Hofmann est le premier à la synthétiser et à en améliorer les capacités thérapeutiques utéro-constrictives qui est commercialisé sous le nom Methergine; c'est en cherchant d'autres molécules actives selon la même méthode qu'il synthétise le LSD en 1938.

En médecine, les dérivés de l'ergot de seigle sont des molécules utilisées en particulier dans le traitement des crises de migraine.

Aspect culturels et historiques

Il fut autrefois responsable

d'une maladie, l'ergotisme, appelée au Moyen Âge mal des Ardents ou feu de

Saint-Antoine![]() , liée à la présence d'ergot

dans le seigle utilisé pour fabriquer le pain. Cette maladie, qui dure jusqu'au

XVII siècle, se présente sous forme d'hallucinations passagères, similaires

à ce que provoque le LSD, et à une vasoconstriction artériolaire, suivie de

la perte de sensibilité des extrémités des différents membres, comme les

bouts des doigts. À cette époque, il était communément admis que ces

personnes étaient des victimes de sorcellerie ou de démons. Saint Antoine

est le saint-patron des ergotiques.

, liée à la présence d'ergot

dans le seigle utilisé pour fabriquer le pain. Cette maladie, qui dure jusqu'au

XVII siècle, se présente sous forme d'hallucinations passagères, similaires

à ce que provoque le LSD, et à une vasoconstriction artériolaire, suivie de

la perte de sensibilité des extrémités des différents membres, comme les

bouts des doigts. À cette époque, il était communément admis que ces

personnes étaient des victimes de sorcellerie ou de démons. Saint Antoine

est le saint-patron des ergotiques.

Selon Mary Matossian, l'ergot de seigle aurait fait partie des causes de la Grande Peur de 1789. Il a été évoqué comme explication possible des visions de certains saints et pour le cas de Jeanne d'Arc.

Pont-Saint-Esprit, 1951

Pendant l'été 1951, une série d'intoxications alimentaires frappe la France, dont la plus sérieuse à partir du 17 août à Pont-Saint-Esprit, où elle fait sept morts, 50 internés dans des hôpitaux psychiatriques et 250 personnes affligées de symptômes plus ou moins graves ou durables. Le corps médical pense alors que le pain maudit aurait pu contenir de l'ergot de seigle, mais sans en avoir la preuve. Le pain acheté dans la boulangerie Briand provoque vomissements, maux de têtes, douleurs gastriques, musculaires, et accès de folie (convulsions démoniaques, hallucinations et tentatives de suicide), troubles pouvant évoquer l'ergotisme. La ville est prise de panique; un journal, cité par l'historien Steven L. Kaplan, observe :

Alors, faute du nom du mal, on veut connaître celui de l'homme responsable. Les versions les plus abracadabrantes circulent. On accuse le boulanger [ancien candidat RPF, protégé d'un conseiller général de Charles de Gaulle], son mitron, puis l'eau des fontaines, puis les modernes machines à battre, les puissances étrangères, la guerre bactériologique, le diable, la SNCF, le pape, Staline, l'Église, les nationalisations.

Les spiripontains applaudissent l'arrestation d'un meunier poitevin, fournisseur de la farine employée à Pont-Saint-Esprit, incarcéré à Nîmes, avant de s'élever contre sa libération.

Plus de cinquante ans après les évènements de Pont-Saint-Esprit, on ne sait toujours pas à quoi les attribuer. Cliniquement, les symptômes étaient ceux d'une forme mixte d'ergotisme, mais ce diagnostic n'a pu être prouvé. On a pensé également à une intoxication par le dicyandiamide de métyl-mercure, un produit contenu dans un fongicide utilisé pour la conservation des grains, mais cette piste a fini par être abandonnée. En 1982, le professeur Moreau, spécialiste des moisissures, a émis l'hypothèse que l'intoxication de Pont-Saint-Esprit aurait pu provenir de mycotoxines, substances produites par des moisissures pouvant se développer dans les silos à grain, dont les effets toxiques sont maintenant bien connus en médecine vétérinaire, mais qui étaient quasiment inconnus en 1951. Mais là encore rien n'a pu être prouvé, et les spécialistes sont en désaccord. En définitive, l'affaire du pain maudit de Pont-Saint-Esprit conserve, à ce jour, tout son mystère.