Lessico

Nerone

Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus

Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus: imperatore romano (Anzio 37 - Roma

68). Figlio di Gneo Domizio Enobarbo e di Agrippina Minore, quindi discendente

di Augusto![]() , dopo un'adolescenza repressa, per le abili manovre della madre,

venne adottato nel 50 dall'imperatore Claudio

, dopo un'adolescenza repressa, per le abili manovre della madre,

venne adottato nel 50 dall'imperatore Claudio![]() del quale sposò la figlia

Ottavia. Tanto si adoperò Agrippina per lui presso Claudio che il figlio di

questi, Britannico, fu escluso dalla successione.

del quale sposò la figlia

Ottavia. Tanto si adoperò Agrippina per lui presso Claudio che il figlio di

questi, Britannico, fu escluso dalla successione.

Morto nel 54 Claudio, avvelenato dalla stessa Agrippina, i pretoriani

acclamarono Nerone, appena diciassettenne, imperatore e il Senato lo riconobbe

come tale. Consigliato da Seneca![]() , che la madre gli aveva dato come

precettore, e da Burro, prefetto del pretorio, nei primi tempi Nerone improntò

i suoi atti di governo a moderazione concedendo alleggerimenti fiscali,

tenendosi fedele la guardia pretoriana con donativi, promuovendo controlli

dell'operato dei governatori provinciali, usando mitezza verso tutti (quando

firmò la prima condanna a morte disse che avrebbe preferito non saper

scrivere).

, che la madre gli aveva dato come

precettore, e da Burro, prefetto del pretorio, nei primi tempi Nerone improntò

i suoi atti di governo a moderazione concedendo alleggerimenti fiscali,

tenendosi fedele la guardia pretoriana con donativi, promuovendo controlli

dell'operato dei governatori provinciali, usando mitezza verso tutti (quando

firmò la prima condanna a morte disse che avrebbe preferito non saper

scrivere).

Indotto dai suoi consiglieri, allontanò gradualmente dalle cose di governo l'invadente madre, ma quando costei si volse a Britannico, Nerone lo fece uccidere nel 55, recuperando però subito il favore popolare, scosso dal delitto, con la costruzione di un immenso anfiteatro in legno, con generosi donativi, con provvedimenti amministrativi equi e ponderati (dimise per esempio l'intrigante liberto Pallante e fece condannare il delatore Suillio). Le vittorie di Corbulone in Armenia valsero anch'esse a rafforzare la sua posizione. Ma nel 59, per tagliar corto con gli intrighi di Agrippina, la fece assassinare.

Nerone e la madre Agrippina

Esiliò poi Ottavia, che successivamente eliminò, e sposò Poppea. Morto nel 62 Burro e messo da parte Seneca, Nerone governò da allora con una politica personale, assecondato dalla stessa Poppea e dal nuovo prefetto Tigellino, dando libero sfogo alle sue inclinazioni artistiche: mirava con ciò a distogliere i Romani dai rozzi ludi gladiatori volgendoli invece a svaghi più umani con feste, spettacoli, agoni, nei quali si esibiva lui stesso come cantante o citaredo, obbligando quelli del seguito a fare altrettanto con scandalo dei tradizionalisti.

Si venne così a creare uno stato di tensione tra lui e l'aristocrazia, che

portò al ripristino della legge di lesa maestà. Per fortuna di Nerone sui

confini vigilavano valorosi generali: Domizio Corbulone in Armenia dove i

Parti![]() furono indotti a patti, Svetonio Paolino in Britannia dove fu domata

Boudicca la ribelle regina degli Iceni, e Vespasiano nella Giudea in rivolta.

Del grande incendio divampato a Roma nel 64, per sviare i sospetti attizzati

dalla propaganda avversaria, accusò come autori i cristiani che, detestati

dalla gente, furono oggetto della prima persecuzione. L'incendio offrì

l'occasione a Nerone di intraprendere una grandiosa opera di ricostruzione

della città sulla base di più razionali criteri urbanistici. Offrì pure

l'occasione di dare il nome Nero

all'utilissimo programma di copia dei CD e dei DVD, che vengono

"bruciati" col laser.

furono indotti a patti, Svetonio Paolino in Britannia dove fu domata

Boudicca la ribelle regina degli Iceni, e Vespasiano nella Giudea in rivolta.

Del grande incendio divampato a Roma nel 64, per sviare i sospetti attizzati

dalla propaganda avversaria, accusò come autori i cristiani che, detestati

dalla gente, furono oggetto della prima persecuzione. L'incendio offrì

l'occasione a Nerone di intraprendere una grandiosa opera di ricostruzione

della città sulla base di più razionali criteri urbanistici. Offrì pure

l'occasione di dare il nome Nero

all'utilissimo programma di copia dei CD e dei DVD, che vengono

"bruciati" col laser.

Preso ormai da mania di grandezza, nella circostanza si costruì

sull'Esquilino un immenso e sontuoso palazzo, la Domus

Aurea. Le grandi spese che ne seguirono misero in difficoltà l'erario

e Nerone fu costretto a svalutare il denaro e a promuovere processi per

confiscare i patrimoni degli avversari. Sventata la congiura dei Pisoni nel

65, nella quale si trovarono implicati, tra gli altri, Seneca, Lucano![]() , Trasea

Peto, capo dell'opposizione senatoria, e Petronio

, Trasea

Peto, capo dell'opposizione senatoria, e Petronio![]() , arbiter elegantiae,

tutti giustiziati o suicidatisi, Nerone cercò di conservarsi l'appoggio dei

ceti minuti con iniziative improntate a una sfacciata demagogia spettacolare.

, arbiter elegantiae,

tutti giustiziati o suicidatisi, Nerone cercò di conservarsi l'appoggio dei

ceti minuti con iniziative improntate a una sfacciata demagogia spettacolare.

Nerone

e Seneca

di Eduardo Barrón - Cordoba - Spagna

Nel 66, morta Poppea, forse per un calcio da lui datole, e sposata Statilia Messalina, lasciato Elio, un liberto, al governo di Roma, si recò in Grecia dove partecipò a corse di carri e a concorsi di poesia: in quell'occasione proclamò la libertà dei Greci e progettò il taglio dell'istmo di Corinto. Rientrato nel 68, celebrò in Roma un grandioso trionfo apollineo ormai tutto preso, come già Caligola, da suggestioni dispotiche alla maniera orientale. Sospettoso di tutti, ordinò a Corbulone e ai due fratelli Scriboni, governatori della Germania, di uccidersi. E intanto una rivolta scoppiò in Gallia su iniziativa del legato Giulio Vindice. La rivolta fu domata, ma vi aderirono con i propri eserciti Galba in Spagna e Clodio Macro in Africa.

Nerone e Poppea

In Roma l'opinione pubblica era ormai contro Nerone per i numerosi delitti e per le sue megalomanie esibizioniste: il suo filellenismo, anche se in lui l'amore per l'arte era sincero, aveva finito con l'urtare il sentimento nazionale romano. Tradito dal prefetto del pretorio Ninfidio, Nerone fu proclamato dal Senato nemico pubblico: costretto a rifugiarsi in una villa suburbana, vi si fece uccidere da Epafrodito, suo liberto, esclamando la famosa frase «quale artista perisce con me». Sei mesi dopo era già rimpianto dal popolino e dai soldati, ma i cristiani lo considerarono l'Anticristo e in Oriente si credeva di averlo visto tre volte.

Per una valutazione d'insieme su Nerone occorre tener presente la giovane età in cui assunse il potere, dopo un'adolescenza repressa, e l'inevitabile tendenza a forme di dispotismo e tirannia quando, non più guidato da esperti consiglieri, si trovò solo a reggere l'impero senza adeguata preparazione, in balia di cortigiani che ne esaltarono l'estro poetico e artistico come strumento irresistibile di governo.

L'effigie di Nerone è nota da monete e da ritratti plastici, non tutti, però, di sicura identificazione. Tipici appaiono il volto carnoso, la barba ricciuta che copre la gola e le guance, la pettinatura a ciocche ondulate. Tra i ritratti più noti sono quello giovanile del Palatino (Roma, Museo Nazionale Romano) e quello in bronzo della Biblioteca Vaticana.

In teatro è soprattutto il personaggio più compiuto e più inquietante della tragedia Britannicus (1669) di Jean Racine; ma è anche protagonista assoluto di molti altri testi che a lui s'intitolano, tra i quali un'anonima tragedia inglese del 1624, un fortunato copione in versi di Pietro Cossa del 1872, un poema drammatico di Arrigo Boito pubblicato nel 1901 e rappresentato postumo nel 1924 alla Scala con musica dello stesso autore, una devastante parodia di Ettore Petrolini rappresentata nel 1918 e tradotta in film da Alessandro Blasetti nel 1930, e un'opera di Mascagni eseguita alla Scala nel 1935. Tra le opere più recenti si cita un Nerone è morto? dell'ungherese Miklos Hubay, rappresentato dallo Stabile di Torino nel 1974. Per antonomasia, il nome dell'imperatore è entrato nel linguaggio comune a indicare persona crudele, feroce.

Nerone

Nerone Claudio Cesare Augusto Germanico (latino: Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus; Anzio, 15 dicembre 37 – Roma, 9 giugno 68) è stato un imperatore romano. Nato con il nome di Lucio Domizio Enobarbo, fu il quinto e ultimo imperatore della dinastia giulio-claudia succedendo a suo zio Claudio nell'anno 54 e governò per 14 anni fino al suicidio all'età di trent'anni.

Nacque ad Anzio il 15 dicembre 37, da Agrippina Minore e Gneo Domizio Enobarbo. Il padre apparteneva alla famiglia dei Domizi Enobarbi, una stirpe considerata di "nobiltà plebea" (ovvero recente), mentre la madre era figlia dell'acclamato condottiero Germanico, nipote di Marco Antonio, di Agrippa e di Augusto, nonché sorella dell'imperatore Caligola che quindi era suo zio materno. Nel 39 Agrippina Minore, sua madre, descritta da molti come spietatamente ambiziosa, fu scoperta coinvolta in una congiura contro il fratello Caligola, e venne quindi mandata in esilio nell'isola di Pandataria. L'anno seguente il marito di lei, Gneo, morì e il suo patrimonio venne confiscato da Caligola stesso.

Lucio nel frattempo fu affidato alle cure della zia Domizia Lepida e alle nutrici Egogle e Alessandra. Essendo la zia di non elevata condizione economica, in questi primi anni i precettori furono un barbiere e un ballerino, dal quale Lucio avrebbe imparato l'amore per la danza e per lo spettacolo. Nel 41 Caligola venne assassinato e Agrippina Minore poté ritornare a Roma e occuparsi del figlio dell'età di quattro anni, e attraverso il quale aveva intenzione di attuare la propria opera di rivalsa. Lucio venne affidato a due liberti greci (Aniceto e Berillo) per poi proseguire gli studi con due sapienti dell'epoca: Cheremone d'Alessandria e Alessandro di Ege, grazie ai quali il giovane allievo sviluppò il proprio filoellenismo.

Nel 49 Agrippina Minore sposò l'imperatore Claudio, che era suo zio, e ottenne la revoca dell'esilio di Seneca, allo scopo di servirsi del celebre filosofo quale nuovo precettore del figlio. Inoltre, visto che il giovane Lucio dimostrava maggior affetto verso la zia Domizia Lepida, Agrippina per gelosia la fece accusare di avere complottato contro l'imperatore, ottenendone da Claudio la condanna a morte. Nell'occasione, l'undicenne Lucio fu minacciato e costretto dalla madre a testimoniare contro la zia e, poco dopo, venne fidanzato con Ottavia, figlia di Claudio, di otto anni.

Dopo la salita di Nerone al potere nel 55, quando aveva soli diciassette anni, Britannico, figlio legittimo di Claudio, sarebbe stato fatto uccidere per volere di Sesto Afranio Burro, forse con il coinvolgimento di Seneca. Entrambi i personaggi rimpiazzarono Agrippina nella sua influenza sul giovane imperatore.

Il primo scandalo del regno di Nerone coincise col suo primo matrimonio, considerato incestuoso, con la sorellastra Claudia Ottavia, figlia di Claudio. Nerone più tardi divorziò da lei quando s'innamorò di Poppea. Questa, descritta come una donna notevolmente bella, sarebbe stata coinvolta, prima del matrimonio con l'imperatore, in una storia d'amore con Marco Salvio Otone, amico di Nerone stesso. Nel 59 Poppea fu sospettata d'aver organizzato l'omicidio di Agrippina, mentre Otone venne inviato come governatore in Lusitania, l'odierno Portogallo.

Nel 62 Nerone sposò Poppea dopo aver ripudiato Claudia Ottavia per sterilità e averla relegata in Campania. Alcune manifestazioni popolari in favore della prima moglie convinsero l'Imperatore della necessità di eliminarla, dopo averla accusata di tradimento. Lo stesso anno Burro morì, forse ucciso per ordine di Nerone, e Seneca si ritirò a vita privata; la carica di prefetto del Pretorio venne assegnata a Tigellino (già esiliato da Caligola per adulterio con Agrippina). Contemporaneamente venne introdotta una serie di leggi sul tradimento, che provocarono l'esecuzione di numerose condanne capitali. Nel 63 Nerone e Poppea ebbero una figlia, Claudia Augusta, che tuttavia morì ancora in fasce.

Allo scoppio del grande incendio di Roma del 64, l'imperatore si trovava ad Anzio, ma raggiunse immediatamente l'Urbe per conoscere l'entità del pericolo e decidere le contromisure, organizzando in modo efficiente i soccorsi, partecipando in prima persona agli sforzi per spegnere l'incendio. Nerone mise sotto accusa i Cristiani residenti a Roma, già malvisti dalla popolazione, quali autori del disastro; alcuni di loro vennero arrestati e messi a morte. Venne poi accusato, dopo la sua morte, di aver provocato egli stesso l'incendio. Nonostante la ricostruzione dei fatti sia incerta e molti aspetti della vicenda siano ancora controversi, l'immagine iconografica dell'imperatore che suona la lira mentre Roma bruciava è ormai ampiamente superata e considerata inattendibile. Al contrario, l'imperatore aprì addirittura i suoi giardini per mettere in salvo la popolazione e si attirò l'odio dei patrizi facendo sequestrare imponenti quantitativi di derrate alimentari per sfamarla. In occasione dei lavori di ricostruzione, Nerone dettò nuove e lungimiranti regole edilizie, destinate a frenare gli eccessi della speculazione e tracciare un nuovo impianto urbanistico, sul quale è tutt'ora fondata la città. In tale occasione egli iniziò la costruzione del faraonico complesso edilizio noto come Domus Aurea, la sua residenza personale, che giunse a comprendere il Palatino, le pendici dell'Esquilino (Oppio) e parte del Celio.

Nel 65 venne scoperta la congiura pisoniana (così chiamata da Caio Calpurnio Pisone) e i cospiratori, tra cui anche Seneca, vennero costretti al suicidio. La stessa sorte toccò anche Gneo Domizio Corbulone. In quel periodo, poi, secondo la tradizione cristiana, Nerone ordinò anche la decapitazione di San Paolo e, più tardi, la crocifissione di San Pietro. Nel 66, morì Poppea, che secondo le fonti sarebbe stata uccisa da un calcio al ventre dello stesso Nerone durante una lite, mentre era in attesa del suo secondogenito.

L'anno successivo, nel 67, l'imperatore viaggiò fra le isole della Grecia, a bordo di una lussuosa galea sulla quale divertiva gli ospiti (fra questi anche tutti gli stupefatti notabili delle città visitate e tributarie di Roma, compresa Atene) con prestazioni artistiche, mentre a Roma Ninfidio Sabino (collega di Tigellino, che aveva preso il posto dei congiurati pisoniani) andava procurandosi il consenso di pretoriani e senatori. Prima di lasciare la Grecia, annunciò personalmente - ponendosi al centro dello stadio d'Istmia, presso Corinto, prima della celebrazione dei giochi panellenici - la decisione di restituire la libertà alle poleis, eliminando il governo provinciale di Roma. Dell'evento parla Svetonio (Nero XIX, 24) e il testo del discorso di Nerone è pervenuto tramite un'iscrizione (Dittenberger SIG III ed. 814 = SIG II ed. 376): L'imperatore dice: Volendo contraccambiare la nobilissima Grecia della benevolenza e venerazione nei miei confronti, ordino che il maggior numero di persone di questa provincia siano presenti a Corinto il 28 novembre. Essendo convenuta la folla in adunanza, egli proclamò quanto segue: Greci! Concedo a voi un dono inatteso, quantunque non del tutto insperato da parte della mia magnanimità, tanto grande quanto non siete arrivati a chiedere: tutti voi Greci che abitate l'Achaia e quello che fino ad ora è stato il Peloponneso: ricevete la libertà e l'immunità (eleutheria, aneisphoria), che neanche nei periodi più felici avete tutti avuto, perché eravate schiavi o di stranieri o l'uno dell'altro. Oh! se avessi potuto concedere questo dono quando la Grecia era all'apice della potenza, perché più persone potessero godere del mio favore! Per questo biasimo il tempo che ha consumato la grandezza del mio favore. E ora vi reco questo beneficio non per pietà, ma per benevolenza e contraccambio gli dei, la cui benevola presenza ho sempre sperimentato sia per terra sia per mare, per il fatto che mi hanno concesso di beneficiare in maniera così grande. Infatti anche altri hanno liberato città e capi, ma Nerone ha liberato l'intera provincia. Il sacerdote a vita degli Augusti e di Nerone Claudio Cesare Augusto [...]"

Sotto Nerone, il re della Partia Vologese I pose sul trono del regno d'Armenia il proprio fratello Tiridate, sul finire del 54. Questo convinse Nerone che fosse necessario avviare preparativi di guerra in vista di un'imminente campagna militare. Domizio Corbulone fu inviato a sedare le continue scaramucce tra le popolazioni locali e sparuti gruppi di romani. In realtà non vi fu una vera guerra fino al 58. Dopo la conquista di Artaxata nel 58 e della città di Tigranocesta nel 59, pose sul trono dei Parti re Tigrane IV nel 60. Il nuovo re non era molto favorevole all'influenza dei romani e il fratello Tiridate si sostituì al medesimo nel 64. Si spense così l'ultimo focolaio di guerra e Nerone poté fregiarsi del titolo di Imperator (Pacator) incoronando a Roma il re Tiridate I e inaugurando,nel contempo, i festeggiamenti per la ricorrenza del trecentesimo anniversario della prima chiusura delle porte del tempio di Giano (236 aC.) per la pace ecumenica raggiunta in tutto l'impero. Nerone fece coniare una moneta sulla quale, nel dritto appare la sua figura con il capo incoronato e l' aspetto fiero riportante la scritta: imp nero caesar avg germ e sul rovescio il tempio di Giano "a porte chiuse" con la scritta: pace p r ubiq partaianvm clvsit s c. Per la prima volta dunque un imperatore di Roma si fregiò del titolo di Imperatore. Nel corso del suo principato continuò la conquista della Britannia, anche se negli anni 60-61 fu interrotta da una rivolta capeggiata da una certa Boudicca la ribelle regina degli Iceni.

Gaio Giulio Vindice, governatore della Gallia Lugdunense, si ribellò dopo il ritorno dell'imperatore a Roma, e questo spinse Nerone a una nuova ondata repressiva: fra gli altri ordinò il suicidio al generale Servio Sulpicio Galba, allora governatore nelle province ispaniche: questi, privo di alternative, dichiarò la sua fedeltà al Senato e al popolo romano, non riconoscendo più l'autorità di Nerone. Si ribellò quindi anche Lucio Clodio Macero, comandante della III legione Augusta in Africa, bloccando la fornitura di grano per la città di Roma. Nimfidio corruppe i pretoriani, che si ribellarono a loro volta a Nerone, con la promessa di somme di denaro da parte di Galba. Infine il Senato lo depose e Nerone si suicidò il 9 giugno 68, si dice, aiutato dal liberto Epafrodito. Venne sepolto in un'urna di porfido, sormontata da un altare di marmo lunense, collocata nel Sepolcro dei Domizi, sotto l'attuale basilica di Santa Maria del Popolo. Con la sua morte terminò la dinastia giulio-claudia.

« Obiit tricensimo et secundo aetatis anno, die quo quondam Octaviam interemerat, tantumque gaudium publice praebuit, ut plebs pilleata tota urbe discurreret. et tamen non defuerunt qui per longum tempus vernis aestivisque floribus tumulum eius ornarent ac modo imagines praetextatas in rostris proferrent, modo edicta quasi viventis et brevi magno inimicorum malo reversuri. Quin etiam Vologaesus Parthorum rex missis ad senatum legatis de instauranda societate hoc etiam magno opere oravit, ut Neronis memoria coloretur. denique cum post viginti annos adulescente me extitisset condicionis incertae qui se Neronem esse iactaret, tam favorabile nomen eius apud Parthos fuit, ut vehementer adiutus et vix redditus sit. »

« Morì nel suo trentaduesimo anno d'età, nel giorno anniversario dell'uccisione di Ottavia e fu tale la gioia di tutti che il popolo corse per le strade col pileo. Tuttavia non mancarono quelli che, per lungo tempo, ornarono di fiori la sua tomba, in primavera e in estate, e che esposero sui rostri ora le immagini di lui vestito di pretesta, ora gli editti con i quali annunciava, come se fosse ancora vivo, il suo prossimo ritorno per la rovina dei suoi nemici. Per di più, Vologeso, re dei Parti, quando mandò ambasciatori al Senato per riconfermare l'alleanza, fece chiedere anche, insistentemente, che si onorasse la memoria di Nerone. Infine, vent'anni dopo la sua morte, durante la mia adolescenza, venne fuori un tale, di ignota estrazione, che pretendeva di essere Nerone e questo nome gli valse tanto favore presso i Parti che essi lo sostennero energicamente e solo a malincuore lo riconsegnarono. » (Svetonio, Vita dei Cesari, Nero LVII)

Fu detto anche "Il porrofago" perché era ghiotto di porri. Questo ortaggio, diceva, gli serviva per schiarirsi la voce. Nutrì, secondo Svetonio, oltre che una sfrenata passione per la musica e il canto, anche una discreta passione per la pittura e la scultura. Svetonio parla anche delle sue personali qualità artistiche ricordando come avesse scritto molti componimenti poetici originali.

« Itaque ad poeticam pronus carmina libenter ac sine labore composuit nec, ut quidam putant, aliena pro suis edidit. venere in manus meas pugillares libellique cum quibusdam notissimis versibus ipsius chirographo scriptis, ut facile appareret non tralatos aut dictante aliquo exceptos, sed plane quasi a cogitante atque generante exaratos; ita multa et deleta et inducta et superscripta inerant. »

« Essendo incline alla poesia, compose versi volentieri e senza fatica e non pubblicò mai, come insinuano alcuni, quelli degli altri spacciandoli per suoi. Mi sono capitati tra mano taccuini e libretti che contengono alcuni suoi versi assai noti scritti di sua mano ed è facile vedere che non sono stati né copiati né scritti sotto dettatura, ma sicuramente composti da un uomo che medita e crea, perché vi sono molte cancellature, annotazioni e inserimenti. » (Svetonio, Vita dei Cesari, Nero LII)

Si cimentò anche pubblicamente come suonatore di cetra. La notizia secondo cui avesse assistito all'incendio di Roma suonando questo strumento è un falso: allo scoppio dell'incendio, Nerone si trovava nella sua villa di Anzio e si precipitò a Roma per dirigere l'opera di spegnimento e i soccorsi, ai quali partecipò in prima persona.

Stando al trattato storico politico di Tacito, Nerone amava passare il suo tempo nella residenza estiva di Torre di Gianus, dove amava deliziare il palato dei suoi ospiti con delicati manicaretti da lui stesso preparati.

Nerone, oltre alla famosa ricostruzione di Roma a seguito dell'incendio del 64, intraprese altre opere pubbliche tra cui due imprese sovrumane iniziate ma mai completate: il taglio dell'istmo di Corinto e un canale lungo la costa dall'Averno a Roma. La prima opera, già tentata dal tiranno Peliandro, dal Re di Macedonia Demetrio Poliorcete, da Giulio Cesare e da Caligola sembrava non portare fortuna a chi la intraprendeva, tutti morti in modo violento. Gli scavi furono segnati da episodi nefasti e si interruppero con la morte dell'ideatore. Il canale dall'Averno a Roma (lungo 250 km), ancora più mastodontico di quello di Corinto, assorbì risorse umane ed economiche immense e non fu mai completato a causa degli infiniti problemi tecnici.

L'immagine di Nerone ci è stata tramandata dai resoconti degli storici in modo del tutto negativo: ciò è dovuto principalmente al fatto che durante il suo principato prevalsero intrighi e omicidi sia nella corte imperiale che nella società civile. Il diritto romano fu sempre più tralasciato a favore di un dispotismo tirannico che nasceva anche dalla concezione filoellenizzante che egli aveva sul suo ruolo di principe quasi divino. In tal senso egli si impegnò in una politica di netta opposizione alla classe senatoriale, unica parte della società che poteva arginare il suo potere assoluto, in modo simile a quanto fece l'imperatore Caligola, suo zio. La sua tendenza teocratica, sull'esempio delle monarchie orientali, fu del resto sempre invisa alla maggioranza degli storici antichi, di rango aristocratico e di stampo filorepubblicano.

L'immagine negativa di Nerone è stata tramandata anche dagli storici cristiani in quanto egli è stato l'autore della prima persecuzione contro i cristiani. Durante queste prime persecuzioni ne furono martirizzati moltissimi, nonché i vertici della Chiesa Romana, cioè San Pietro e San Paolo. Queste furono solo le prime atrocità commesse verso i fedeli della nuova religione e che proseguirono anche dopo l'incendio dell'anno 64, riprese con virulenza da altri imperatori altrettanto sanguinari. Si è ritenuto, addirittura, che Nerone fosse l'anticristo poiché la somma del valore numerico delle lettere che compongono le parole "Cesare Nerone" in lingua ebraica è 666, il numero della Bestia di Satana.

Contrariamente alla storiografia ufficiale, il popolo della città continuò a tributargli una sorta di spontaneo culto popolare fino al XII secolo, quando papa Pasquale II interruppe la tradizione di portar fiori al mausoleo dei Domizi-Enobarbi, ritenuto la tomba di Nerone, nei primi giorni di giugno, facendone demolire i resti e facendo costruire al suo posto una cappella che sarebbe poi divenuta Santa Maria del Popolo. In seguito, una tomba monumentale sulla Via Cassia fu popolarmente creduta il sepolcro di Nerone tanto che, ancora oggi, la zona dove sorge viene chiamata Tomba di Nerone. L'equivoco nacque, probabilmente, per la mancanza di indicazioni sul sepolcro marmoreo che fece credere che questa fosse la tomba dell'Imperatore sottoposto alla Damnatio memoriae. Oggi è stato appurato che questo sepolcro appartiene al console Publio Vibio Mariano.

Bust of Nero at Musei Capitolini - Rome

Reign 13 October, 54 – 9 June, AD 68 (Proconsul from 51) - Full name Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (from birth to AD 50) - Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus (from 50 to accession) - Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (as emperor) - Born 15 December 37 (37-12-15) - Birthplace Antium - Died 9 June 68 (aged 30) - Place of death Just outside Rome - Buried Mausoleum of the Domitii Ahenobarbi, Pincian Hill, Rome - Predecessor Claudius - Successor Galba - Wives Claudia Octavia, Poppaea Sabina, Statilia Messalina - Offspring Claudia Augusta -Dynasty Julio-Claudian - Father Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus - Mother Agrippina the Younger .

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, also called Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus, was the fifth and last Roman emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Nero was adopted by his great uncle Claudius to become heir to the throne. As Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, he succeeded to the throne on 13 October 54, following Claudius's death.

Nero ruled from 54 to 68, focusing much of his attention on diplomacy, trade, and increasing the cultural capital of the empire. He ordered the building of theaters and promoted athletic games. His reign included a successful war and negotiated peace with the Parthian Empire (58–63), the suppression of the British revolt (60–61) and improving relations with Greece. The First Roman-Jewish War (66–70) started during his reign. In 68 a military coup drove Nero from the throne. Facing assassination, he committed suicide on 9 June 68.

Nero's rule is often associated with tyranny and extravagance. He is known for a number of executions, including those of his mother and step-brother, as the emperor who "fiddled while Rome burned", and as an early persecutor of Christians. This view is based upon the main surviving sources for Nero's reign — Tacitus, Suetonius and Cassius Dio. Few surviving sources paint Nero in a favorable light. Some sources, though, including those mentioned above, portray him as an emperor who was popular with the common Roman people, especially in the East. The study of Nero is problematic as some modern historians question the reliability of ancient sources when reporting on Nero's tyrannical acts.

Roman imperial dynasties -

Julio-Claudian dynasty

Augustus 27 BC – 14 AD

Tiberius 14 AD – 37 AD

Caligula 37 AD – 41 AD

Claudius 41 AD – 54 AD

Nero 54 AD – 68 AD

Family

Nero was born with the name Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus on 15 December, AD 37, in Antium, near Rome. He was the only son of 12, by Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, and second and third cousin Agrippina the Younger, sister of emperor Caligula.

Lucius' father was the grandson of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Aemilia Lepida through their son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. Gnaeus was a grandson to Mark Antony and Octavia Minor through their daughters Antonia Major and Antonia Minor, by each parent. With Octavia, he was the grandnephew of Caesar Augustus. Nero's father had been employed as a praetor and was a member of Caligula's staff when the latter traveled to the East. Nero's father was described by Suetonius as a murderer and a cheat who was charged by emperor Tiberius with treason, adultery, and incest. Tiberius died, allowing him to escape these charges. Nero's father died of edema (or "dropsy") in 39 AD when Nero was three.

Lucius' mother was Agrippina the Younger, who was great-granddaughter to Caesar Augustus and his wife Scribonia through their daughter Julia the Elder and her husband Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. Agrippina's father, Germanicus, was grandson to Augustus's wife, Livia, on one side and to Mark Antony and Octavia on the other. Germanicus' mother Antonia Minor, was a daughter of Octavia Minor and Mark Antony. Octavia was Augustus' second elder sister. Germanicus was also the adoptive son of Tiberius. A number of ancient historians accuse Agrippina of murdering her third husband, emperor Claudius.

In the book "The Lives of the Twelve Caesars" the Roman historian Suetonius describes Nero as "about the average height, his body marked with spots and malodorous, his hair light blond, his features regular rather than attractive, his eyes blue and somewhat weak, his neck over thick, his belly prominent, and his legs very slender."

Rise to power

Nero was not expected ever to become emperor because his maternal uncle, Caligula, had begun his reign at the age of 25 with ample time to produce his own heir. Lucius' mother, Agrippina, lost favor with Caligula and was exiled in 39 after her husband's death. Caligula seized Lucius's inheritance and sent him to be raised by his less wealthy aunt, Domitia Lepida. Caligula, his wife Caesonia and their infant daughter Julia Drusilla were murdered in 41. These events led Claudius, Caligula's uncle, to become emperor. Claudius allowed Agrippina to return from exile.

Claudius had married twice before marrying Messalina. His previous marriages produced three children including a son, Drusus, who died at a young age. He had two children with Messalina - Claudia Octavia (b. 40) and Britannicus (b. 41) Messalina was executed by Claudius in 48. In 49, Claudius married a fourth time, to Agrippina. To aid Claudius politically, Lucius was officially adopted in 50 and renamed Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus. Nero was older than his stepbrother, Britannicus, and became heir to the throne. Nero was proclaimed an adult in 51 at the age of 14. He was appointed proconsul, entered and first addressed the Senate, made joint public appearances with Claudius, and was featured in coinage. In 53, he married his stepsister Claudia Octavia.

Emperor

Aureus of Nero and his mother, Agrippina, c. 54.

Claudius died in 54 and Nero was established as emperor. Though accounts vary greatly, many ancient historians state Agrippina poisoned Claudius. It is not known how much Nero knew or was involved in the death of Claudius. Nero became emperor at 16, the youngest emperor up until that time. Ancient historians describe Nero's early reign as being strongly influenced by his mother Agrippina, his tutor Lucius Annaeus Seneca, and the Praetorian Prefect Sextus Afranius Burrus, especially in the first year. Other tutors were less often mentioned, such as Alexander of Aegae. Very early in Nero's rule, problems arose from competition for influence between Agrippina and Nero's two main advisers, Seneca and Burrus.

Seneca and Nero, after Eduardo Barrón, Cordoba, Spain.

In 54, Agrippina tried to sit down next to Nero while he met with an Armenian envoy, but Seneca stopped her and prevented a scandalous scene. Nero's personal friends also mistrusted Agrippina and told Nero to beware of his mother. Nero was reportedly unsatisfied with his marriage to Octavia and entered an affair with Claudia Acte, a former slave. In 55, Agrippina attempted to intervene in favor of Octavia and demanded that her son dismiss Acte. Nero, with the support of Seneca, resisted the intervention of his mother in his personal affairs. With Agrippina's influence over her son severed, she reportedly began pushing for Britannicus, Nero's stepbrother, to become emperor. Nearly fifteen-year-old Britannicus, heir-designate prior to Nero's adoption, was still legally a minor, but was approaching legal adulthood. According to Tacitus, Agrippina hoped that with her support, Britannicus, being the blood son of Claudius, would be seen as the true heir to the throne by the state over Nero. However, the youth died suddenly and suspiciously on 12 February, 55, the very day before his proclamation as an adult had been set. Nero claimed that Britannicus died from an epileptic seizure, but ancient historians all claim Britannicus' death came from Nero's poisoning him. After the death of Britannicus, Agrippina was accused of slandering Octavia and Nero ordered her out of the imperial residence.

Matricide and consolidation of power

Coin of Nero and Poppaea Sabina

Over time, Nero became progressively more powerful, freeing himself of his advisers and eliminating rivals to the throne. In 55, he removed Marcus Antonius Pallas, an ally of Agrippina, from his position in the treasury. Pallas, along with Burrus, was accused of conspiring against the emperor to bring Faustus Sulla to the throne. Seneca was accused of having relations with Agrippina and embezzlement. Seneca was successfully able to have himself, Pallas and Burrus acquitted. According to Cassius Dio, at this time, Seneca and Burrus reduced their role in governing from careful management to mere moderation of Nero.

In 58, Nero became romantically involved with Poppaea Sabina, the wife of his friend and future emperor Otho. Reportedly because a marriage to Poppaea and a divorce from Octavia did not seem politically feasible with Agrippina alive, Nero ordered the murder of his mother in 59. A number of modern historians find this an unlikely motive as Nero did not marry Poppaea until 62. Additionally, according to Suetonius, Poppaea did not divorce her husband until after Agrippina's death, making it unlikely that the already married Poppaea would be pressing Nero for marriage. Some modern historians theorize that Nero's execution of Agrippina was prompted by her plotting to set Rubellius Plautus on the throne. According to Suetonius, Nero tried to kill his mother through a planned shipwreck, but when she survived, he had her executed and framed it as a suicide. The incident is also recorded by Tacitus.

The Remorse of Nero after Killing his Mother,

by John William Waterhouse,

1878.

In 62 Nero's adviser, Burrus, died. Additionally, Seneca was again faced with embezzlement charges. Seneca asked Nero for permission to retire from public affairs. Nero divorced and banished Octavia on grounds of infertility, leaving him free to marry the pregnant Poppaea. After public protests, Nero was forced to allow Octavia to return from exile, but she was executed shortly after her return. Nero also was reported to have kicked Poppaea to death in 65 before she could have his second child. However, modern historians, noting Suetonius, Tacitus and Cassius Dio's possible bias against Nero and the likelihood that they did not have eyewitness accounts of private events, postulate that Poppaea may have died because of complications of miscarriage or childbirth.

Accusations of treason being plotted against Nero and the Senate first appeared in 62. The Senate ruled that Antistius, a praetor, should be put to death for speaking ill of Nero at a party. Later, Nero ordered the exile of Fabricius Veiento who slandered the Senate in a book. Tacitus writes that the roots of the conspiracy led by Gaius Calpurnius Piso began in this year. To consolidate power, Nero executed a number of people in 62 and 63 including his rivals Pallas, Rubellius Plautus and Faustus Sulla. According to Suetonius, Nero "showed neither discrimination nor moderation in putting to death whomsoever he pleased" during this period. Nero's consolidation of power also included a slow usurping of authority from the Senate. In 54, Nero promised to give the Senate powers equivalent to those under Republican rule. By 65, senators complained that they had no power left and this led to the Pisonian conspiracy.

Administrative policies

Coin showing Nero distributing charity to a citizen c. 64-66.

Over the course of his reign, Nero often made rulings that pleased the lower class. Nero was criticised as being obsessed with being popular. Nero began his reign in 54 by promising the Senate more autonomy. In this first year, he forbade others to refer to him with regard to enactments, for which he was praised by the Senate. Nero was known for spending his time visiting brothels and taverns during this period. In 55, Nero began taking on a more active role as an administrator. He was consul four times between 55 and 60. During this period, some ancient historians speak fairly well of Nero and contrast it with his later rule.

Under Nero, restrictions were put on the amount of bail and fines. Also, fees for lawyers were limited. There was a discussion in the Senate on the misconduct of the freedmen class, and a strong demand was made that patrons should have the right of revoking freedom. Nero supported the freedmen and ruled that patrons had no such right. The Senate tried to pass a law in which the crimes of one slave applied to all slaves within a household. Nero vetoed the measure. After tax collectors were accused of being too harsh to the poor, Nero transferred collection authority to lower commissioners. Nero banned any magistrate or procurator from exhibiting public entertainment for fear that the venue was being used as a method to sway the populace. Additionally, there were many impeachments and removals of government officials along with arrests for extortion and corruption. When further complaints arose that the poor were being overly taxed, Nero attempted to repeal all indirect taxes. The Senate convinced him this action would bankrupt the public treasury. As a compromise, taxes were cut from 4.5% to 2.5%. Additionally, secret government tax records were ordered to become public. To lower the cost of food imports, merchant ships were declared tax-exempt.

In imitation of the Greeks, Nero built a number of gymnasiums and theatres. Enormous gladiatorial shows were also held. Nero also established the quinquennial Neronia. The festival included games, poetry and theatre. Historians indicate that there was a belief that theatre led to immorality. Others considered that to have performers dressed in Greek clothing was old fashioned. Some questioned the large public expenditure on entertainment.

In 64, Rome burned. Nero enacted a public relief effort as well as significant reconstruction. A number of other major construction projects occurred in Nero's late reign. Nero had the marshes of Ostia filled with rubble from the fire. He erected the large Domus Aurea. In 67, Nero attempted to have a canal dug at the Isthmus of Corinth. Ancient historians state that these projects and others exacerbated the drain on the State's budget. The economic policy of Nero is a point of debate among scholars. According to ancient historians, Nero's construction projects were overly extravagant and the large number of expenditures under Nero left Italy "thoroughly exhausted by contributions of money" with "the provinces ruined." Modern historians, though, note that the period was riddled with deflation and that it is likely that Nero's spending came in the form of public works projects and charity intended to ease economic troubles.

Great Fire of Rome

The Great Fire of Rome erupted on the night of 18 July to 19 July, AD 64. The fire started at the southeastern end of the Circus Maximus in shops selling flammable goods. The extent of the fire is uncertain. According to Tacitus, who was nine at the time of the fire, it spread quickly and burned for over five days. It completely destroyed four of fourteen Roman districts and severely damaged seven. The only other historian who lived through the period and mentioned the fire is Pliny the Elder, who wrote about it in passing. Other historians who lived through the period (including Josephus, Dio Chrysostom, Plutarch, and Epictetus) make no mention of it. It is uncertain who or what actually caused the fire — whether accident or arson. Suetonius and Cassius Dio favor Nero as the arsonist, so he could build a palatial complex. Tacitus mentions that Christians confessed to the crime, but it is not known whether these confessions were induced by torture. However, fires started accidentally were common in ancient Rome. In fact, Rome suffered another large fire in 69 and in 80.

It was said by Suetonius and Cassius Dio that Nero sang the "Sack of Ilium" in stage costume while the city burned. Popular legend claims that Nero played the fiddle at the time of the fire, an anachronism based merely on the concept of the lyre, a stringed instrument associated with Nero and his performances. (There were no fiddles in 1st-century Rome.) Tacitus's account, however, has Nero in Antium at the time of the fire. Tacitus also said that Nero playing his lyre and singing while the city burned was only rumor. According to Tacitus, upon hearing news of the fire, Nero returned back to Rome to organize a relief effort, which he paid for from his own funds. After the fire, Nero opened his palaces to provide shelter for the homeless, and arranged for food supplies to be delivered in order to prevent starvation among the survivors. In the wake of the fire, he made a new urban development plan. Houses after the fire were spaced out, built in brick, and faced by porticos on wide roads. Nero also built a new palace complex known as the Domus Aurea in an area cleared by the fire. This included lush artificial landscapes and a 30 meter statue of himself, the Colossus of Nero. The size of this complex is debated (from 100 to 300 acres). To find the necessary funds for the reconstruction, tributes were imposed on the provinces of the empire.

According to Tacitus, the population searched for a scapegoat and rumors held Nero responsible. To deflect blame, Nero targeted Christians. He ordered Christians to be thrown to dogs, while others were crucified and burned. Tacitus described the event:“Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians [or Chrestians] by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.”

Public performances

Nero coin, c. 66. Ara Pacis on the reverse.

Nero enjoyed driving a one-horse chariot, singing to the harp and poetry. He even composed songs that were performed by other entertainers throughout the empire. At first, Nero only performed for a private audience.

In 64, Nero began singing in public in Neapolis in order to improve his popularity. He also sang at the second quinquennial Neronia in 65. It was said that Nero craved the attention, but historians also write that Nero was encouraged to sing and perform in public by the Senate, his inner circle and the people. Ancient historians strongly criticize his choice to perform, calling it shameful.

Nero was convinced to participate in the Olympic Games of 67 in order to improve relations with Greece and display Roman dominance. As a competitor, Nero raced a ten-horse chariot and nearly died after being thrown from it. He also performed as an actor and a singer. Though Nero faltered in his racing (in one case, dropping out entirely before the end) and acting competitions, he won these crowns nevertheless and paraded them when he returned to Rome. The victories are attributed to Nero bribing the judges and his status as emperor.

War and peace with Parthia

Shortly after Nero's accession to the throne in 55, the Roman vassal kingdom of Armenia overthrew their prince Rhadamistus and he was replaced with the Parthian prince Tiridates. This was seen as a Parthian invasion of Roman territory. There was concern in Rome over how the young emperor would handle the situation. Nero reacted by immediately sending the military to the region under the command of Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo. The Parthians temporarily relinquished control of Armenia to Rome. The peace did not last and full-scale war broke out in 58. The Parthian king Vologases I refused to remove his brother Tiridates from Armenia. The Parthians began a full-scale invasion of the Armenian kingdom. Commander Corbulo responded and repelled most of the Parthian army that same year. Tiridates retreated and Rome again controlled most of Armenia. Nero was acclaimed in public for this initial victory. Tigranes, a Cappadocian noble raised in Rome, was installed by Nero as the new ruler of Armenia. Corbulo was appointed governor of Syria as a reward.

Nero's peace deal with Parthia was a political victory at home and made him beloved in the east. In 62, Tigranes invaded the Parthian province of Adiabene. Again, Rome and Parthia were at war and this continued until 63. Parthia began building up for a strike against the Roman province of Syria. Corbulo tried to convince Nero to continue the war, but Nero opted for a peace deal instead. There was anxiety in Rome about eastern grain supplies and a budget deficit. The result was a deal where Tiridates again became the Armenian king, but was crowned in Rome by emperor Nero. In the future, the king of Armenia was to be a Parthian prince, but his appointment required approval from the Romans. Tiridates was forced to come to Rome and partake in ceremonies meant to display Roman dominance. This peace deal of 63 was a considerable victory for Nero politically. Nero became very popular in the eastern provinces of Rome and with the Parthians as well. The peace between Parthia and Rome lasted 50 years until emperor Trajan of Rome invaded Armenia in 114.

Other major power struggles and rebellions

The war with Parthia was not Nero's only major war but he was both criticized and praised for an aversion to battle. Like many emperors, Nero faced a number of rebellions and power struggles within the empire.

In 60, a major rebellion broke out in the province of Britannia. While the governor Gaius Suetonius Paullinus and his troops were busy capturing the island of Mona (Anglesey) from the druids, the tribes of the south-east staged a revolt led by queen Boudica of the Iceni. Boudica and her troops destroyed three cities before the army of Paullinus was able to return, be reinforced and put down the rebellion in 61. Fearing Paullinus himself would provoke further rebellion, Nero replaced him with the more passive Publius Petronius Turpilianus.

In 65, Gaius Calpurnius Piso, a Roman statesman, organized a conspiracy against Nero with the help of Subrius Flavus and Sulpicius Asper, a tribune and a centurion of the Praetorian Guard. According to Tacitus, many conspirators wished to "rescue the state" from the emperor and restore the Republic. The freedman Milichus discovered the conspiracy and reported it to Nero's secretary, Epaphroditos. As a result, the conspiracy failed and its members were executed including Lucan, the poet. Nero's previous advisor, Seneca was ordered to commit suicide after admitting he discussed the plot with the conspirators.

In 66, there was a Jewish revolt in Judea stemming from Greek and Jewish religious tension. In 67, Nero dispatched Vespasian to restore order. This revolt was eventually put down in 70, after Nero's death. This revolt is famous for Romans breaching the walls of Jerusalem and destroying the Second Temple of Jerusalem.

In March 68, Gaius Julius Vindex, the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, rebelled against Nero's tax policies. Lucius Verginius Rufus, the governor of Germania Superior, was ordered to put down Vindex's rebellion. In an attempt to gain support from outside his own province, Vindex called upon Servius Sulpicius Galba, the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, to join the rebellion and further, to declare himself emperor in opposition to Nero. At the Battle of Vesontio in May 68, Verginius' forces easily defeated those of Vindex and the latter committed suicide. However after putting down this one rebel, Verginius' legions attempted to proclaim their own commander as emperor. Verginius refused to act against Nero, but the discontent of the legions of Germany and the continued opposition of Galba in Spain did not bode well for Nero. While Nero had retained some control of the situation, support for Galba increased despite his being officially declared a public enemy. The prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Gaius Nymphidius Sabinus, also abandoned his allegiance to the emperor and came out in support for Galba.

In response, Nero fled Rome with the intention of going to the port of Ostia and from there to take a fleet to one of the still-loyal eastern provinces. However he abandoned the idea when some army officers openly refused to obey his commands, responding with a line from Vergil's Aeneid: "Is it so dreadful a thing than to die?" Nero then toyed with the idea of fleeing to Parthia, throwing himself upon the mercy of Galba, or to appeal to the people and beg them to pardon him for his past offences "and if he could not soften their hearts, to entreat them at least to allow him the prefecture of Egypt". Suetonius reports that the text of this speech was later found in Nero's writing desk, but that he dared not give it from fear of being torn to pieces before he could reach the Forum. Nero returned to Rome and spent the evening in the palace. After sleeping, he awoke at about midnight to find the palace guard had left. Dispatching messages to his friends' palace chambers for them to come, none replied. Upon going to their chambers personally, all were abandoned. Upon calling for a gladiator or anyone else adept with a sword to kill him, no one appeared. He cried "Have I neither friend nor foe?" and ran out as if to throw himself into the Tiber.

Returning again, Nero sought for some place where he could hide and collect his thoughts. An imperial freedman offered his villa, located 4 miles outside the city. Travelling in disguise, Nero and four loyal servants reached the villa, where Nero ordered them to dig a grave for him. As it was being prepared, he said again and again "What an artist dies in me!". At this time a courier arrived with a report that the Senate had declared Nero a public enemy and that it was their intention to execute him by beating him to death. At this news Nero prepared himself for suicide. Losing his nerve, he first begged for one of his companions to set an example by first killing himself. At last, the sound of approaching horsemen drove Nero to face the end. After quoting a line from Homer's Iliad ("Hark, now strikes on my ear the trampling of swift-footed coursers!") Nero drove a dagger into his throat. In this he was aided by his private secretary, Epaphroditos. When one of the horsemen entered, upon his seeing Nero all but dead he attempted to stanch the bleeding. With the words "Too late! This is fidelity!", Nero died on 9 June 68. This was the anniversary of the death of Octavia. Nero was buried in the Mausoleum of the Domitii Ahenobarbi, in what is now the Villa Borghese (Pincian Hill) area of Rome. With his death, the Julio-Claudian dynasty came to an end. Chaos ensued in the Year of the Four Emperors.

After death

According to Suetonius and Cassius Dio, the people of Rome celebrated the death of Nero. Tacitus, though, describes a more complicated political environment. Tacitus mentions that Nero's death was welcomed by Senators, nobility and the upper-class. The lower-class, slaves, frequenters of the arena and the theatre, and "those who were supported by the famous excesses of Nero", on the other hand, were upset with the news. Members of the military were said to have mixed feelings, as they had allegiance to Nero, but were bribed to overthrow him. Eastern sources, namely Philostratus II and Apollonius of Tyana, mention that Nero's death was mourned as he "restored the liberties of Hellas with a wisdom and moderation quite alien to his character" and that he "held our liberties in his hand and respected them."

Modern scholarship generally holds that, while the Senate and more well-off individuals welcomed Nero's death, the general populace was "loyal to the end and beyond, for Otho and Vitellius both thought it worthwhile to appeal to their nostalgia." Nero's name was erased from some monuments, in what Edward Champlin regards as "outburst of private zeal". Many portraits of Nero were reworked to represent other figures; according to Eric R. Varner, over fifty such images survive. This reworking of images is often explained as part of the way in which the memory of disgraced emperors was condemned posthumously (see damnatio memoriae). Champlin, however, doubts that the practice is necessarily negative and notes that some continued to create images of Nero long after his death. The legend of Nero's return lasted for hundreds of years after Nero's death. Augustine of Hippo wrote of the legend as a popular belief in 422.

The civil war during the Year of the Four Emperors was described by ancient historians as a troubling period. According to Tacitus, this instability was rooted in the fact that emperors could no longer rely on the perceived legitimacy of the imperial bloodline, as Nero and those before him could. Galba began his short reign with the execution of many allies of Nero and possible future enemies. One notable enemy included Nymphidius Sabinus, who claimed to be the son of emperor Caligula.

Otho overthrew Galba. Otho was said to be liked by many soldiers because he had been a friend of Nero and resembled him somewhat in temperament. It was said that the common Roman hailed Otho as Nero himself. Otho used "Nero" as a surname and reerected many statues to Nero. Vitellius overthrew Otho. Vitellius began his reign with a large funeral for Nero complete with songs written by Nero.

After Nero's suicide in 68, there was a widespread belief, especially in the eastern provinces, that he was not dead and somehow would return. This belief came to be known as the Nero Redivivus Legend.

At least three Nero impostors emerged leading rebellions. The first, who sang and played the cithara or lyre and whose face was similar to that of the dead emperor, appeared in 69 during the reign of Vitellius. After persuading some to recognize him, he was captured and executed. Sometime during the reign of Titus (79-81) there was another impostor who appeared in Asia and also sang to the accompaniment of the lyre and looked like Nero but he, too, was killed. Twenty years after Nero's death, during the reign of Domitian, there was a third pretender. Supported by the Parthians, they hardly could be persuaded to give him up and the matter almost came to war.

Historiography

The history of Nero’s reign is problematic in that no historical sources survived that were contemporary with Nero. These first histories at one time did exist and were described as biased and fantastical, either overly critical or praising of Nero. The original sources were also said to contradict on a number of events. Nonetheless, these lost primary sources were the basis of surviving secondary and tertiary histories on Nero written by the next generations of historians. A few of the contemporary historians are known by name. Fabius Rusticus, Cluvius Rufus and Pliny the Elder all wrote condemning histories on Nero that are now lost. There were also pro-Nero histories, but it is unknown who wrote them or on what deeds Nero was praised.

The bulk of what is known of Nero comes from Tacitus, Suetonius and Cassius Dio, who were all of the Patrician class. Tacitus and Suetonius wrote their histories on Nero over fifty years after his death, while Cassius Dio wrote his history over 150 years after Nero’s death. These sources contradict on a number of events in Nero’s life including the death of Claudius, the death of Agrippina and the Roman fire of 64, but they are consistent in their condemnation of Nero. A handful of other sources also add a limited and varying perspective on Nero. Few surviving sources paint Nero in a favorable light. Some sources, though, portray him as a competent emperor who was popular with the Roman people, especially in the east.

Cassius Dio (c. 155-229) was the son of Cassius Apronianus, a Roman senator. He passed the greater part of his life in public service. He was a senator under Commodus and governor of Smyrna after the death of Septimius Severus; and afterwards suffect consul around 205, as also proconsul in Africa and Pannonia. Books 61–63 of Dio's Roman History describe the reign of Nero. Only fragments of these books remain and what does remain was abridged and altered by John Xiphilinus, an 11th century monk.

Dio Chrysostom (c. 40–120), a Greek philosopher and historian, wrote the Roman people were very happy with Nero and would have allowed him to rule indefinitely. They longed for his rule once he was gone and embraced impostors when they appeared: “Indeed the truth about this has not come out even yet; for so far as the rest of his subjects were concerned, there was nothing to prevent his continuing to be Emperor for all time, seeing that even now everybody wishes he were still alive. And the great majority do believe that he still is, although in a certain sense he has died not once but often along with those who had been firmly convinced that he was still alive.”

Epictetus (c. 55-135) was the slave to Nero's scribe Epaphroditos. He makes a few passing negative comments on Nero's character in his work, but makes no remarks on the nature of his rule. He describes Nero as a spoiled, angry and unhappy man.

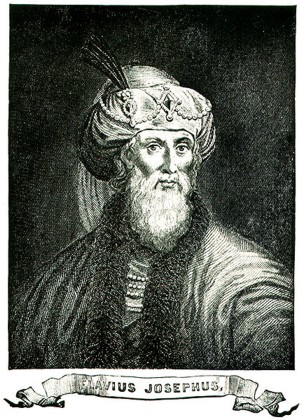

The historian Flavius Josephus (c. 37-100)

accused other historians of slandering

Nero.

The historian Josephus (c. 37-100), while calling Nero a tyrant, was also the first to mention bias against Nero. Of other historians, he said: “But I omit any further discourse about these affairs; for there have been a great many who have composed the history of Nero; some of which have departed from the truth of facts out of favor, as having received benefits from him; while others, out of hatred to him, and the great ill-will which they bare him, have so impudently raved against him with their lies, that they justly deserve to be condemned. Nor do I wonder at such as have told lies of Nero, since they have not in their writings preserved the truth of history as to those facts that were earlier than his time, even when the actors could have no way incurred their hatred, since those writers lived a long time after them.”

Lucan. Though more of a poet than historian, Lucanus (c. 39- 65) has one of the kindest accounts of Nero's rule. He writes of peace and prosperity under Nero in contrast to previous war and strife. Ironically, he was later involved in a conspiracy to overthrow Nero and was executed.

Philostratus II "the Athenian" (c. 172-250) spoke of Nero in the Life of Apollonius Tyana (Books 4–5). Though he has a generally a bad or dim view of Nero, he speaks of others' positive reception of Nero in the East.

Pliny the Elder. The history of Nero by Pliny the Elder (c. 24-79) did not survive. Still, there are several references to Nero in Pliny's Natural Histories. Pliny has one of the worst opinions of Nero and calls him an "enemy of mankind."

Plutarch (c. 46-127) mentions Nero indirectly in his account of the Life of Galba and the Life of Otho. Nero is portrayed as a tyrant, but those that replace him are not described as better.

Seneca the Younger. It is not surprising that Seneca (c. 4 BC-65), Nero's teacher and advisor, writes very well of Nero.

Suetonius (c. 69-130) was a member of the equestrian order, and he was the head of the department of the imperial correspondence. While in this position, Suetonius started writing biographies of the emperors, accentuating the anecdotal and sensational aspects.

Tacitus. The Annals by Tacitus (c. 56-117) is the most detailed and comprehensive history on the rule of Nero, despite being incomplete after the year 66. Tacitus described the rule of the Julio-Claudian emperors as generally unjust. He also thought that existing writing on them was unbalanced: “The histories of Tiberius, Caius, Claudius, and Nero, while they were in power, were falsified through terror, and after their death were written under the irritation of a recent hatred.” Tacitus was the son of a procurator, who married into the elite family of Agricola. He entered his political life as a senator after Nero's death and, by Tacitus' own admission, owed much to Nero's rivals. Realizing that this bias may be apparent to others, Tacitus protests that his writing is true.

Nero and religion

Jewish tradition - At the end of 66, conflict broke out between Greeks and Jews in Jerusalem and Caesarea. According to a Jewish tradition in the Talmud (tractate Gitin 56a-b), Nero went to Jerusalem and shot arrows in all four directions. All the arrows landed in the city. He then asked a passing child to repeat the verse he had learned that day. The child responded "I will lay my vengeance upon Edom by the hand of my people Israel" (Ez. 25,14). Nero became terrified, believing that God wanted the Temple in Jerusalem to be destroyed, but would punish the one to carry it out. Nero said, "He desires to lay waste His House and to lay the blame on me," whereupon he fled and converted to Judaism to avoid such retribution. Vespasian was then dispatched to put down the rebellion. The Talmud adds that the sage Reb Meir Baal Ha Ness, a prominent supporter of the Bar Kokhba rebellion against Roman rule, was a descendant of Nero. Roman sources nowhere report Nero's alleged conversion to Judaism, a religion considered by the Romans as extremely barbaric and immoral. It seems unlikely that such sources - almost universally hostile towards the emperor - would have passed up the opportunity to denigrate Nero even further by mentioning this alleged conversion. Neither is there any record of Nero having any offspring who survived infancy: his only recorded child, Claudia Augusta, died aged 4 months. The legend recorded in the Talmud thus cannot be relied upon as a historical source for facts on Nero's life.

Christian tradition - Early Christian tradition often holds Nero as the first persecutor of Christians and as the killer of Apostles Peter and Paul. There was also a belief among some early Christians that Nero was the Antichrist. The non-Christian historian Tacitus describes Nero extensively torturing and executing Christians after the fire of 64. Suetonius also mentions Nero punishing Christians, though he does so as a praise and does not connect it with the fire. The Christian writer Tertullian (c. 155-230) was the first to call Nero the first persecutor of Christians. He wrote: "Examine your records. There you will find that Nero was the first that persecuted this doctrine". Lactantius (c. 240-320) also said Nero "first persecuted the servants of God" as does Sulpicius Severus. However, Suetonius gives that "since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he [the emperor Claudius] expelled them from Rome" ("Iudaeos impulsore Chresto assidue tumultuantis Roma expulit"). These expelled "Jews" may have been early Christians, although Suetonius is not explicit. Nor is the Bible explicit, calling Aquila of Pontus and his wife, Priscilla, both expelled from Italy at the time, "Jews."

Killer of Peter and Paul. The first text to suggest that Nero killed an apostle is the apocryphal Ascension of Isaiah, a Christian writing from the 2nd century. It says the slayer of his mother, who himself this king, will persecute the plant which the Twelve Apostles of the Beloved have planted. Of the Twelve one will be delivered into his hands. The Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 275-339) was the first to write that Paul was beheaded in Rome during the reign of Nero. He states that Nero's persecution led to Peter and Paul's deaths, but that Nero did not give any specific orders. Several other accounts have Paul surviving his two years in Rome and traveling to Hispania. Peter is first said to have been crucified upside down in Rome during Nero's reign (but not by Nero) in the apocryphal Acts of Peter (c. 200). The account ends with Paul still alive and Nero abiding by God's command not to persecute any more Christians. By the 4th century, a number of writers were stating that Nero killed Peter and Paul.

The Antichrist

The Ascension of Isaiah is the first text to suggest that Nero was the Antichrist. It claims a lawless king, the slayer of his mother,...will come and there will come with him all the powers of this world, and they will hearken unto him in all that he desires. The Sibylline Oracles, Book 5 and 8, written in the 2nd century, speaks of Nero returning and bringing destruction. Within Christian communities, these writings, along with others, fuelled the belief that Nero would return as the Antichrist. In 310, Lactantius wrote that Nero suddenly disappeared, and even the burial-place of that noxious wild beast was nowhere to be seen. This has led some persons of extravagant imagination to suppose that, having been conveyed to a distant region, he is still reserved alive; and to him they apply the Sibylline verses.

In 422, Augustine of Hippo wrote about 2 Thessalonians 2:1–11, where he believed Paul mentioned the coming of the Antichrist. Though he rejects the theory, Augustine mentions that many Christians believed that Nero was the Antichrist or would return as the Antichrist. He wrote, so that in saying, "For the mystery of iniquity doth already work," he alluded to Nero, whose deeds already seemed to be as the deeds of Antichrist.

Most scholars, such as Delbert Hillers (Johns Hopkins University) of the American Schools of Oriental Research and the editors of the Oxford & Harper Collins study Bibles, contend that the number 666 in the Book of Revelation is a code for Nero, a view that is also supported in Roman Catholic Biblical commentaries. When treated as Hebrew numbers, the letters of Nero's name add up either to 616 or 666, representing the two devil numbers given in ancient versions of Revelation and the two ways of spelling his name in Hebrew (NERO and NERON). The concept of Nero as the Antichrist is often a central belief of Preterist eschatology.

Bob Dylan's song "Desolation Row", the final track from Highway 61 Revisited, "Praise be to Nero's Nero Burning ROM is a popular optical disc authoring program; it is a pun mixing the legend of Nero playing his lyre as Rome burned and the colloquial term for optical disc authoring ("burning"). The pun is more obvious in the original German as the German name for Rome is Rom (a literal English translation would be Nero Burning ROMe). The program logo is an image of the Roman Colosseum in flames; this is dramatic but inaccurate, as the Great Fire of Rome took place in 64 AD, while construction of the Colosseum only started a few years later, between 70 and 72 AD.