|

|

218 |

|

Ulisse Aldrovandi

Ornithologiae tomus alter - 1600

Liber

Decimusquartus

qui

est

de Pulveratricibus Domesticis

Book

14th

concerning

domestic

dust bathing fowls

transcribed by Fernando Civardi - translated by Elio Corti - reviewed by Roberto Ricciardi

The navigator's option display -> character -> medium is recommended

|

Octava

rursus die oculi maiores adhuc

videbantur, utpote ciceris ferme magnitudine. Totum corpus tunc sese

velociter movebat, et iam crura, et alae distincte cerni incipiebant.

Rostrum tamen interim muccosum adhuc erat. Sed forte quispiam quaerat,

cur prius superiores, quam inferiores partes in eiusmodi formatione

appareant: cui responsum velim, virtutem, seu facultatem formatricem in

superioribus magis quam in inferioribus vigere, quod spiritales sint, et

per consequens plus caloris obtineant. Caeterum istaec omnia, quae hac

die videbam, sequenti manifestiora apparebant. |

-

Chicken embryo |

|

Decima

die non amplius caput toto

corpore maius erat, magnum tamen, ut in infantibus etiam videmus:

magnitudinis autem causa est humidissima cerebri constitutio. Quod vero

Aristoteles dicit[1]

oculos fabis maiores esse, id

profecto minime verum est, si de vulgaribus nostris fabis locutus fuerit,

cum alioqui ervi, vel ciceris albi magnitudinem non excederent: atque

hinc etiam non absurde quispiam colligat fabas antiquorum fuisse

rotundas, quales araci sunt, quem ideo fabam veterum quidam existimant.

Neque etiam verum est quod tradit[2],

{tunc}, <tunc>, scilicet,

oculos pupillis adhuc carere. Etenim hae non tantum hac die

apparebant, sed duabus etiam praecedentibus, una cum omnibus partibus,

ac humoribus. Quod vero ait detracta

cute nihil solidi videri, sed humorem tantum candidum, rigidum, et

refulgentem ad lucem, nec quicquam aliud, id de crystallino humore

mihi dixisse videtur, qui tamen haud solus apparebat, sed vitreus quoque

et albugineus, unde non parum hallucinatus videri potest Philosophus,

uti etiam Albertus, qui eo tempore nihil duri, et glandulosi in iis

reperiri existimat, cum crystallinus humor solidus sit, ac quam maxime

conspicuus. |

On

the tenth day the head was no longer larger than the entire body, but it

was large nevertheless, as we also see in newborn children: the reason

for its bigness is the very humid constitution of the brain. As to the

fact that Aristotle |

|

Eadem

item die vidi omnia viscera,

nempe cor, iecur, pulmonem. Cor autem, et iecur erant albicantis coloris:

et cordis motus non solum apparebat, antequam foetum aperirem, sed iam

secto etiam thorace moveri videbatur. Erat autem pullus involutus

quartae illi membranae plurimis venis refertae[3],

ne in humore iaceret. Cernebam etiam vasa umbilicalia prope anum ad

umbilicum deferri, ibique infer<r>i, ut cibum per illum petat

foetus. Vidi denique, quod Aristoteles non advertit, in dorso prope

uropygium pennarum principia nigricantia menti humani cuti non absimilia,

cui pili abrasi sint. |

On

the same day I saw all the viscera, that is, heart, liver, lung. The

heart and liver were of a whitish color: and the heart’s movement not

only was evident before I opened the foetus but it seemed to move even

when the thorax had been cut. The chick was wrapped up in that fourth

membrane – amnios - filled with many veins so that it would not become

immersed in the liquid. I also saw the umbilical vasa near the anus

going towards the umbilicus and entering there, so that the foetus might

take its food through it. Finally, I saw something Aristotle does not

mention: on the back near the uropygial gland |

|

Die

subsequenti haec omnia erant

manifestiora, et in superioris rostelli extremitate erat quid albidi,

cartilagineum, et subduriusculum, quod rursus die decimatertia magis

erat conspicuum. Erat autem rotundum milii grano haud absimile.

Sagacissima rerum parens natura id ibi fabricasse videtur, ut impediat,

ne rostello suo vel venulas, vel membranulas, vel alias quascunque

tenerrimas particulas pertundat. Aiunt mulierculae, pullos iam natos

cibum capere non posse nisi prius id auferatur. |

On

the following day all these items were more evident, and on the

extremity of the upper beak there was something whitish, cartilaginous

and rather hard which afterwards, on the 13th day, was more

apparent – the diamond |

|

Decimaquarta

die pullus iam totus plumescebat. Decimaquinta in digitis

ungues albicantes apparebant. Die vero decimasexta ovum aperire placuit

in opposita parte, ubi nativa tunica, sed unica tantummodo apparebat,

eaque alba. Alteram enim quam in altera parte semper videram, hic

observare minime datum est. Itaque dubitabam an ea tantum pro albuminis

tutela nata sit, cum scilicet ovum non sit recens, vel ad pulli

defensionem in ovo incubato. Nam indies illa magis magisque

decidere videtur, et foetum sequi, qui sui gravitate deorsum decidit. |

On

the fourteenth day the chick was already entirely covered with down. On

the fifteenth, whitish nails appeared on its toes. On the sixteenth day

I want to open the egg in the opposite part where was visible the tunic

belonging to the shell, but only one, and it was white too. For the

other one I ever had seen in the opposite side, in this point it is

quite impossible to be observed. Thus I was doubtful whether it took

birth only for the protection of the albumen when the egg is not recent

or for the defense of the chick in the incubated egg. For day by day

this tunic seems to fall down more and more and to follow the foetus,

which falls downward because of its own weight. |

|

Aristoteles

etiam unicam tantum esse eiusmodi tunicam his verbis[4]

videtur innuere. Sunt,

inquit, quandoque locata ova hoc ordine, prima, postremaque ad testam ovi

membrana posita est, non testa ipsius nativa, sed altera illi subiecta:

liquor in ea candidus est, quasi diceret, omnes partes in ovo

locatae sunt hoc ordine; nempe prima, postremaque ad testam ovi membrana

posita est. Intelligit meo iudicio per primam, et postremam membranam,

eas membra<na>s recens in incubato ovo genitas, eas videlicet,

quas aliquoties appellavi tertiam secundinam, et quartam, quam

involventem foetum dixi. Nam cum dicit testae nativam non esse, ostendit

nec primam, nec secundam esse, quae ab altera ovi parte reperitur.

Videtur igitur excludere hanc nativam sive primam, vel secundam, et

intelligere tertiam, quam secundinam saepe vocavi. Cum vero dicit[5],

sed altera illi subiecta, intelligit

eandem, secundinam nempe testae subiectam, quod vel ex hoc maxime liquet,

quod candidum in ea liquorem inesse dicat. Is enim, ut supra ostendi,

inter tertiam, et quartam continetur. Hinc manifesto errore Suessanus

convincitur, qui ex Ephesio per primam interpretatur eam, quae testae

adhaeret, per postremam vero, quae albumini. |

Also

Aristotle by the following words seems to hint that such a tunic is only

one. He says: Since the eggs are set up in this order, set against

the eggshell there are a first and a second membrane, the latter not

being that belonging to the shell, but being the other lying beneath the

first one: there is a snow-white liquid in it, as if he was saying

that in egg all parts are arranged in this order; and precisely that the

first and the second membrane are set against the eggshell. He means,

according to my judgment, by first and last membrane those membranes

recently generated in the incubated egg, of course those which I

sometimes called the third placental one – allantoid - and the fourth

which I said is enveloping the foetus - amnios. For when he says that

the membrane is not belonging to the shell he shows that it is neither

the first, nor the second which is found in the other side of the egg.

He therefore seems to exclude that this one belonging to the shell is

the first or the second, and to understand that it is the third, which

often I called afterbirth. For when he says, but the other lying

beneath it, he means that same membrane, that is the afterbirth one,

set against the shell, and this is very clear also from the fact that he

says there is a snow-white liquid in it. For this liquid, as I showed

above, is contained between the third and fourth ones. Hence the

Suessanus - Agostino Nifo |

|

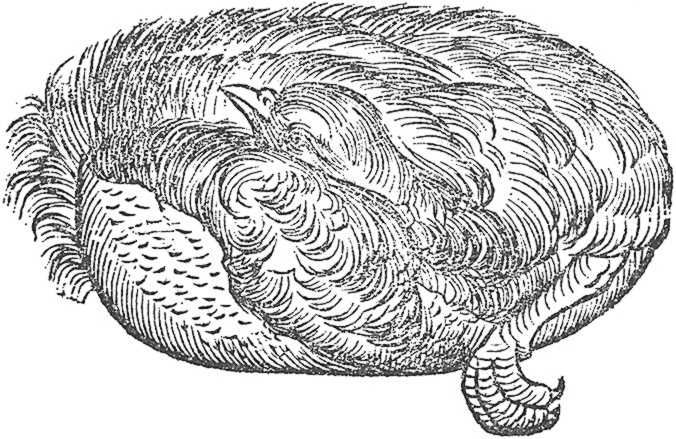

Quae

omnia a nobis observata quotidie in sequentibus

diebus evidentiora, utpote in perfectissimo pullo apparebant. Die vero

vigesima pullus putamine a parente Gallina ablato hora vigesimasecunda

sua sponte exivit. Sequens icon ostendit situm perfecti iam pulli in

utero [ovo?[6]]. |

All

these things I daily observed became more evident in the following days,

since they were appearing in a quite perfected chick. On the twentieth

day, the shell being removed by mother hen, on the twenty-second hour

the chick came out by himself. The following picture shows the position

of a by now completed chick in the uterus. |

[1] Historia animalium VI,3, 561a 30-32: In questo periodo gli occhi sono prominenti, più grandi di una fava e neri; se si asporta la pelle, vi si trova all’interno un liquido bianco e freddo, assai risplendente in piena luce, ma nulla di solido. (traduzione di Mario Vegetti)

[2] Historia animalium VI,3, 561a 28: Esso ha ancora la testa più grande del resto del corpo, e gli occhi più grandi della testa; e tuttora privi della vista. (traduzione di Mario Vegetti)

[3] Stavolta è Aldrovandi che verosimilmente prende un abbaglio in questo farraginoso sovrapporsi di membrane senza un nome specifico. Questa quarta membrana dovrebbe corrispondere all’amnios che, al contrario dell’allantoide, non è vascolarizzato, e dovrebbe corrispondere a quanto riferito da Aldrovandi a pagina 216 quando riporta la descrizione tratta da Aristotele. Infatti a pagina 216 leggiamo: Tum vero membrana alia circa ipsum foetum, ut dictum est, ducitur arcens humorem: sub qua vitellus alia obvolutus membrana, in quem umbelicus [umbilicus] a corde, ac vena maiore oriens pertinet, atque ita efficitur, ne foetus alterutro humore attingatur.

[4] Historia animalium VI,3, 561b 15-18: Ogni parte si trova così disposta nel modo seguente: in primo luogo, all’estrema periferia presso il guscio c’è la membrana dell’uovo, non quella del guscio ma quella al di sotto di essa. In questa è contenuto un fluido bianco, poi il pulcino, e attorno a esso una membrana che lo isola, affinché non sia immerso nel fluido; sotto il pulcino è sito il giallo, a cui porta una delle vene menzionate, mentre l’altra va al bianco circostante. (traduzione di Mario Vegetti)

[5] Historia animalium VI,3, 561b 17: Ogni parte si trova così disposta nel modo seguente: in primo luogo, all’estrema periferia presso il guscio c’è la membrana dell’uovo, non quella del guscio ma quella al di sotto di essa. (traduzione di Mario Vegetti)

[6] Forse non si tratta di una svista di Aldrovandi, bensì di una conseguenza delle elucubrazioni di Aristotele contenute in De generatione animalium e riportate da Aldrovandi a pagina 215, per cui negli ovipari l’uovo corrisponderebbe a un utero materno staccato dalla madre.