Aldrovandi sbolognato

Critica

di William Harvey

all'embriologia di Ulisse Aldrovandi

Il testo

latino è tratto da

Guilielmi Harveii Opera omnia

A Collegio Medicorum Londinensi edita – mdcclxvi

Exercitatio decimaquarta. - De

generatione foetus ex ovo gallinaceo.

14°

esercizio - La generazione del

feto da un uovo di gallina

|

[240] Aristoteles olim, nuperque Hieronymus Fabricius, de generatione et formatione pulli ex ovo, accurate adeo scripserunt, ut pauca admodum desiderari videantur. Ulysses Aldrovandus tamen ovi pullulationem ex suis observationibus descripserit; qua in re, ad Aristotelis auctoritatem potius, quam experientiam ipsam collimasse videtur. Quippe eodem tempore Volcherus Coiter Bononiae degens, eiusdem Ulyssis, praeceptoris sui, ut ait, hortatu, quotidie ova incubata aperuit, plurimaque vere elucidavit, secus quam Aldrovando factum est; quae tamen hunc latere non poterant. Aemilius Parisanus quoque, medicus Venetus, explosis aliorum opinionibus, novam pulli ex ovo procreationem commentus est. |

Un tempo Aristotele, e recentemente Girolamo Fabrizi, scrissero in maniera talmente accurata a proposito della generazione e della formazione del pulcino dall'uovo, che pochissime cose sembrerebbero ritenute necessarie. Tuttavia Ulisse Aldrovandi avrebbe descritto la generazione del pulcino dall'uovo in base alla sue osservazioni; sembra che a questo proposito abbia volto lo sguardo all'autorità di Aristotele anziché all'esperienza vera e propria. Effettivamente nello stesso periodo Volcher Coiter, che abitava a Bologna, su incitamento, come afferma, dello stesso Ulisse suo maestro, aprì ogni giorno delle uova incubate e davvero chiarì molte cose, diversamente da quanto è stato fatto da Aldrovandi, tutte cose che a costui non avrebbero potuto rimanere sconosciute. Anche Emilio Parisano, medico a Venezia, dopo aver disapprovato le idee degli altri, ha inventato una nuova generazione del pulcino dall'uovo. |

Gessner e Coiter osannati

Sbolognare

deriva da Bologna

dove si vendevano oggetti d'oro falso o di poco valore.

In senso figurato

sbolognare

significa liberarsi di una persona sgradita o indiscreta.

Sbolognare

to dump in English

comes from Bologna

where objects of false gold or little value were sold.

In a figurative sense

sbolognare

means to free themselves of an unpleasant or indiscreet person.

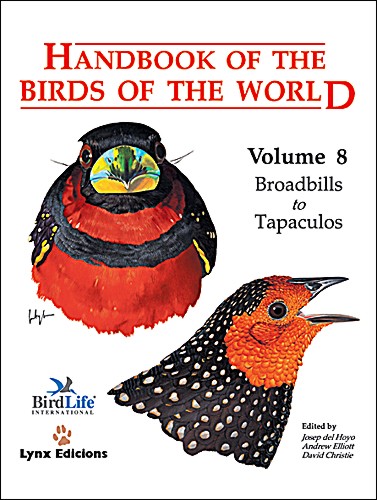

Handbook

of the birds of the world - Volume 8 ![]()

Broadbills to Tapaculos

Edited

by Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliott & David A. Christie

Published by Lynx Edicions – 2003

España

The

beginnings of classifying birds:

the search for a natural system.

by Murray Bruce

Ulisse

Aldrovandi (1522-1605) aveva contribuito al lavoro di Gessner ma, volendo

superarlo, produsse la sua enciclopedica Ornithologia (1599-1603) in

tre volumi. In gioventù era stato imprigionato come eretico, così come per

varie ragioni lo furono Gessner, Belon (lo afferma Murray Bruce) e Coiter. Negli anni successivi

Aldrovandi insegnò botanica. Il suo primo libro fu un trattato sui

medicamenti che dovette essere in grande uso, più tardi si dedicò a lavori

di farmacopea, ma l'ornitologia era il suo interesse principale. La

compilazione, cominciata nel 1560, fu la più completa del suo genere a quei

tempi. Criticò Gessner per l'uso di una classificazione alfabetica e rincorse

a una catalogazione che si rifaceva ad Aristotele. Gli uccelli furono pertanto

raggruppati in base al becco duro e potente (rapaci, pappagalli, corvi,

picchi, rampichini, mangiatori di api e crocieri); in base al fare il bagno solamente

nella polvere o nella polvere e nell'acqua (polli, piccioni e zigoli); in base

all'essere canterini (fringuelli, allodole e canarini), uccelli acquatici,

uccelli di ripa. Dal momento che collocò nella sua opera tutto ciò che

poteva reperire, compresa la scopiazzatura dei lavori di Gessner e di Belon,

di quando in quando il vero valore dell'Ornithologia è stato

considerato come dovuto ai precedenti lavori di questi colleghi a lui

contemporanei. Fu anche criticato per aver incluso poche osservazioni

personali. Comunque venisse giudicato, ai suoi tempi il suo lavoro era

popolare e venne proseguito, per altri gruppi di animali, da molti dei suoi

fedeli studenti dopo la sua morte avvenuta nella natia Bologna, Italia.

(traduzione del testo di Murray Bruce![]() )

)

Birds feature in the earliest records of human cultures

Modern species can be identified from prehistoric cave paintings; also on frescos, pottery, and the like, with some familiar images dating from Ancient Egypt (Houlihan 1996). In one way or another, the earliest cultures also classified the natural world around them. In surviving cultures that still follow traditional lifestyles, the results of anthropological research support the ancient evidence. For example, in New Guinea, classificatory systems matching the details obtained from modern taxonomic studies reveal the extent of the intimate knowledge of the local bird life within individual communities. Diamond (1966) examined results obtained from one village and found that of 120 bird species identified in the area, 110 had local names. While this meant that a few similar species shared the same name, others which can be difficult to identify in the field, such as scrub-wrens (Sericornis spp.), were identified separately. On the other hand, species with distinctive males and females had separate names. Although many names were based on colour, calls or certain habits, others were said to have no meaning.

From what we know of the written records that have come down to us from classical antiquity, the various schools of natural philosophy shared a desire to understand and interpret the world around them. The earliest known works come from Ancient Greece, beginning with Anaximander (611-546 BC) of the school of Ionian philosophers; he described the results of his scientific researches in an influential poem, On Nature. Anaximander was a student of Thales of Miletus (c. 625-547 BC), the earliest philosopher whose writings are known today. However, none of what survives of Thales’s work demonstrates the interest in biology shown by his pupil. Anaximander’s students and disciples, and later others, continued to research and expand their views on the natural world.

The earliest known

comprehensive study of birds dates from the writings of Aristotle![]() (384-322 BC). He was a

disciple of Plato

(384-322 BC). He was a

disciple of Plato![]() (429-347 BC), who in

turn had been a disciple of Socrates

(429-347 BC), who in

turn had been a disciple of Socrates![]() (c. 469-399 BC),

demonstrating the succession of important philosophers who maintained and

developed the ancient traditions, while also taking them in new directions.

Tutor to Alexander the Great

(c. 469-399 BC),

demonstrating the succession of important philosophers who maintained and

developed the ancient traditions, while also taking them in new directions.

Tutor to Alexander the Great![]() (356-323 BC), Aristotle

spent several years travelling and living in various places before he settled

in Athens. These travels provided him with opportunities to make observations

that later found their way into his writings. In his On the History of

Animals, he presented the results of his attempts to study all animal life

known to him, supplying many details, notably about their external appearance,

internal structure and habits. He also attempted the first classification of

birds. He used two main systematic categories, the genos, a large group,

and the eidos, the individual animal forms, roughly equivalent to the

modern terms of order and species. The genos Ornithes was divided into

five smaller groups: 1. Gamsonyches (birds of prey); 2. Steganopodes

(swimming birds); 3. Peristeroides (pigeons and doves); 4. Apodes

(swifts, swallows and martins); 5. all others not included in the four

divisions. With the exception of the swallows and martins, all passerines were

lumped together, along with forms such as woodpeckers. In spite of his

detailed work, many of the 170 kinds of bird he listed remain unidentifiable.

(356-323 BC), Aristotle

spent several years travelling and living in various places before he settled

in Athens. These travels provided him with opportunities to make observations

that later found their way into his writings. In his On the History of

Animals, he presented the results of his attempts to study all animal life

known to him, supplying many details, notably about their external appearance,

internal structure and habits. He also attempted the first classification of

birds. He used two main systematic categories, the genos, a large group,

and the eidos, the individual animal forms, roughly equivalent to the

modern terms of order and species. The genos Ornithes was divided into

five smaller groups: 1. Gamsonyches (birds of prey); 2. Steganopodes

(swimming birds); 3. Peristeroides (pigeons and doves); 4. Apodes

(swifts, swallows and martins); 5. all others not included in the four

divisions. With the exception of the swallows and martins, all passerines were

lumped together, along with forms such as woodpeckers. In spite of his

detailed work, many of the 170 kinds of bird he listed remain unidentifiable.

Although Aristotle’s

works greatly influenced his successors and followers, later Greek

philosophers moved away from studying nature in such detail. Eventually

Aristotle’s works were virtually forgotten and a focus on developing a

workable classification system moved to the world of Ancient Rome where

summarizing knowledge in an encyclopaedic form was well established. Gaius Plinius Secundus![]() (AD 23-79), better known

as Pliny the Elder, followed this trend and amassed everything he could into a

series of 37 “books” collectively entitled Historia Naturalis.

Birds were covered in the tenth book, where he placed great importance on the

structure of the feet as the basis of his arrangement, but his texts were a

disorderly collection of information, with details from folklore, magic and

superstition mingled amongst general information, including personal

observations. Recipes and medical cures also featured in early works covering

birds and, along with everything else, such details were repeated for

centuries.

(AD 23-79), better known

as Pliny the Elder, followed this trend and amassed everything he could into a

series of 37 “books” collectively entitled Historia Naturalis.

Birds were covered in the tenth book, where he placed great importance on the

structure of the feet as the basis of his arrangement, but his texts were a

disorderly collection of information, with details from folklore, magic and

superstition mingled amongst general information, including personal

observations. Recipes and medical cures also featured in early works covering

birds and, along with everything else, such details were repeated for

centuries.

This compendium,

generally unreliable from a zoological perspective, was very influential on

the writings of the later Roman and early Christian times. In fact, for almost

1500 years, Pliny’s encyclopaedia, in particular, was highly regarded and it

was copied, extracted and adapted over the centuries. However, in other areas

Pliny’s work was only one of various sources used, and only when they could

be reconciled with Christian morality. Around the year 370 Christian teachers,

most probably based in Alexandria, sought religious significance in bird and

animal stories to present allegories supporting the doctrines of the

Scriptures. The resulting compilation from Greek, Egyptian and Jewish sources,

marrying natural history with moral theology, was known as the Physiologus![]() , and it was widely

translated. In the meantime, other allegorical works appeared, which were

collectively known as Bestiaries. With some updating from time to time, these

were the sources for information on animals through the period known in Europe

as the Dark Ages.

, and it was widely

translated. In the meantime, other allegorical works appeared, which were

collectively known as Bestiaries. With some updating from time to time, these

were the sources for information on animals through the period known in Europe

as the Dark Ages.

The philosophical

differences between religious doctrine and scientific thought continued in the

Eastern Roman Empire, where the Emperor Justinian I (483-565) decided in 529

to close all Greek schools in order to suppress competition with those of the

Christian church. This movement against secular learning spread. In Spain,

Isidore![]() (570-636), Bishop of

Seville preserved what he could from the censorship of ideas contrary to

Christian teaching in an encyclopaedic work where classical learning could

serve the needs of the students of the church. The result was Etymologiae

sive origines, or simply the Etymologia. Birds were treated in

Chapter 7 of his Book XII on animals. For birds he established the term

“aves” because birds travelled by pathless ways or roads (viae).

Misinformation dominates the chapter, showing the deterioration of knowledge

of the natural world after several centuries.

(570-636), Bishop of

Seville preserved what he could from the censorship of ideas contrary to

Christian teaching in an encyclopaedic work where classical learning could

serve the needs of the students of the church. The result was Etymologiae

sive origines, or simply the Etymologia. Birds were treated in

Chapter 7 of his Book XII on animals. For birds he established the term

“aves” because birds travelled by pathless ways or roads (viae).

Misinformation dominates the chapter, showing the deterioration of knowledge

of the natural world after several centuries.

Aristotle had not been

completely forgotten, and Severinus Boethius (480-524), a keen collector of

Greek documents, was the first to translate some of his writings into Latin,

but this had little influence. Scholars in Syria, beginning with Porphyry![]() (233 - c. 304), had also

extensively translated and commented on his works, and by the period 800-1100,

most of Aristotle’s works had been translated into Arabic. The Arab scholars

were mainly based in Baghdad, where Greek science and philosophy were widely

studied. The two best known translators around this time, who also put their

own interpretations on his works, were Avicenna

(233 - c. 304), had also

extensively translated and commented on his works, and by the period 800-1100,

most of Aristotle’s works had been translated into Arabic. The Arab scholars

were mainly based in Baghdad, where Greek science and philosophy were widely

studied. The two best known translators around this time, who also put their

own interpretations on his works, were Avicenna![]() (980-1037) and,

particularly, Averroes

(980-1037) and,

particularly, Averroes![]() (1126-1198), who lived

in Spain, then occupied by Moslems, after their invasion in the eighth century.

(1126-1198), who lived

in Spain, then occupied by Moslems, after their invasion in the eighth century.

The Aristotle that became

influential in European universities of the time owed much to the

philosophical views of Averroes. Around 1230 the polyglot scholar Michael Scot![]() (1175-1232) travelled to

Spain, where he could read Aristotle in the original Arabic of both Averroes

and Avicenna. He subsequently translated Averroes’s work into Latin. Frederick II of Hohenstaufen

(1175-1232) travelled to

Spain, where he could read Aristotle in the original Arabic of both Averroes

and Avicenna. He subsequently translated Averroes’s work into Latin. Frederick II of Hohenstaufen![]() (1194-1250) was keenly interested in birds and

invited Scot to his court to share his knowledge of Aristotle. Frederick found

Aristotle’s Historia Animalium to be inadequate when compared to his

own knowledge of birds, which he put in a book, De arte venandi cum avibus.

It was much more than just a book on hunting with birds, as it also included a

classification of birds based on ecology and diet. This enlightened work was

well ahead of its time. However, it was ignored by the ecclesiastical

naturalists of the period because of Frederick’s excommunication by the

Pope. Although a version was eventually printed as late as in 1596, its value

to ornithology only began to be appreciated in 1788. A complete version, based

on all available sources, finally appeared only 60 years ago (Wood & Fyfe

1943).

(1194-1250) was keenly interested in birds and

invited Scot to his court to share his knowledge of Aristotle. Frederick found

Aristotle’s Historia Animalium to be inadequate when compared to his

own knowledge of birds, which he put in a book, De arte venandi cum avibus.

It was much more than just a book on hunting with birds, as it also included a

classification of birds based on ecology and diet. This enlightened work was

well ahead of its time. However, it was ignored by the ecclesiastical

naturalists of the period because of Frederick’s excommunication by the

Pope. Although a version was eventually printed as late as in 1596, its value

to ornithology only began to be appreciated in 1788. A complete version, based

on all available sources, finally appeared only 60 years ago (Wood & Fyfe

1943).

The re-emergence of Aristotle continued when two

Dominicans rediscovered his work and wrote commentaries. Albert von Bollstädt![]() (1193-1280), better known as Albertus Magnus, a teacher of theology, used

Scot’s translation and later wrote commentaries on it in De Animalibus,

between 1260 and 1270 (first printed in 1478). His disciple, Thomas de

Cantimpré (c. 1210-1293) had already done this in De Natura Rerum,

between 1233 and 1248. A century later, De Natura Rerum gained wider

circulation when selected parts of it were translated into German by Conrad

von Megenberg (c. 1309-1374) as Das Buch der Natur, first published,

with wood cuts, in 1475. These works originated as attempts to separate

philosophy and theology in understanding the natural world, but they still

carried much misinformation. Times were slowly changing, however, and even

Albertus and later scholars of the period, notably William of Occam

(1270-1347), were able to reconcile natural and church philosophies so that

Aristotle could stand as a representation of the views of the church.

(1193-1280), better known as Albertus Magnus, a teacher of theology, used

Scot’s translation and later wrote commentaries on it in De Animalibus,

between 1260 and 1270 (first printed in 1478). His disciple, Thomas de

Cantimpré (c. 1210-1293) had already done this in De Natura Rerum,

between 1233 and 1248. A century later, De Natura Rerum gained wider

circulation when selected parts of it were translated into German by Conrad

von Megenberg (c. 1309-1374) as Das Buch der Natur, first published,

with wood cuts, in 1475. These works originated as attempts to separate

philosophy and theology in understanding the natural world, but they still

carried much misinformation. Times were slowly changing, however, and even

Albertus and later scholars of the period, notably William of Occam

(1270-1347), were able to reconcile natural and church philosophies so that

Aristotle could stand as a representation of the views of the church.

The spread of what became known as the Renaissance movement began in the

fifteenth century, through the effects of several major events. Those of

significance to the classification of birds included: the exile of Greek

scholars in Europe, from as early as about 1430 but particularly after the

fall of Constantinople in 1453; the invention of printing; and, later, the

discovery of the New World. One Greek scholar, Theodorus Gaza![]() , brought Aristotle’s works with him and as early as 1476 published in

Latin the Libri de Animalibus, with a Greek edition appearing in 1495.

Printing made books widely available, with the ancient texts and knowledge

reaching a much broader readership. The beginnings of extensive global

exploration provided new insights for understanding the diversity of the

natural world.

, brought Aristotle’s works with him and as early as 1476 published in

Latin the Libri de Animalibus, with a Greek edition appearing in 1495.

Printing made books widely available, with the ancient texts and knowledge

reaching a much broader readership. The beginnings of extensive global

exploration provided new insights for understanding the diversity of the

natural world.

It was at this point in history that the man later called the Father of

Ornithology appeared. William Turner![]() (c. 1500-1568) was a widely travelled naturalist both in his native

England and in Europe, often not by choice but because of religious

differences. He turned his interest in philology to classical natural history

and sought to make an accurate interpretation of the names in the works of

Aristotle and Pliny, publishing his results in his little book Avium præcipuarum,

quarum apud Plinium et Aristotelem mentio est, brevis et succincta historia

(1544). He also included many of his own extensive observations, making it the

first bird book treated in a scientific spirit. In his lifetime, he published

31 books on plants and animals, all praised for their accuracy, and indeed he

is also known as the Father of English Botany (Mullens 1908a). Turner

concluded his studies by hoping that a new Aristotle would emerge to revise

and update what was known about natural history. He did not have long to wait.

(c. 1500-1568) was a widely travelled naturalist both in his native

England and in Europe, often not by choice but because of religious

differences. He turned his interest in philology to classical natural history

and sought to make an accurate interpretation of the names in the works of

Aristotle and Pliny, publishing his results in his little book Avium præcipuarum,

quarum apud Plinium et Aristotelem mentio est, brevis et succincta historia

(1544). He also included many of his own extensive observations, making it the

first bird book treated in a scientific spirit. In his lifetime, he published

31 books on plants and animals, all praised for their accuracy, and indeed he

is also known as the Father of English Botany (Mullens 1908a). Turner

concluded his studies by hoping that a new Aristotle would emerge to revise

and update what was known about natural history. He did not have long to wait.

Conrad

Gessner![]() (1516-1565), based in Switzerland, was a great assembler and organizer

of information. He was assisted in his work by several correspondents,

including Turner, whose work he greatly admired. Birds were covered in the

third volume of his Historia Animalium (1555), popularized by

reprintings, in Germany in particular, for over a century. In this work he

discussed and illustrated 217 different birds, including those of mythology,

even though he did not believe they existed, but because he thought it would

be of interest to the public. Gessner’s work has been credited as

representing the starting point of modern zoology. His earlier bibliographical

studies have given him the name of the Father of Bibliography, and he also

wrote an account of 130 known languages, with the Lord’s Prayer given in 22

of them. He was also perhaps the first person to collect natural history

objects and house them in a museum. As classification was poorly understood,

he decided to present his encyclopaedic coverage of birds alphabetically. He

died when plague ravaged his home city of Zurich.

(1516-1565), based in Switzerland, was a great assembler and organizer

of information. He was assisted in his work by several correspondents,

including Turner, whose work he greatly admired. Birds were covered in the

third volume of his Historia Animalium (1555), popularized by

reprintings, in Germany in particular, for over a century. In this work he

discussed and illustrated 217 different birds, including those of mythology,

even though he did not believe they existed, but because he thought it would

be of interest to the public. Gessner’s work has been credited as

representing the starting point of modern zoology. His earlier bibliographical

studies have given him the name of the Father of Bibliography, and he also

wrote an account of 130 known languages, with the Lord’s Prayer given in 22

of them. He was also perhaps the first person to collect natural history

objects and house them in a museum. As classification was poorly understood,

he decided to present his encyclopaedic coverage of birds alphabetically. He

died when plague ravaged his home city of Zurich.

Pierre Belon![]() (1517-1564) travelled widely in Greece, Asia Minor, Egypt and Arabia,

and wrote a popular account of his travels, including natural history (1553).

He lived in various parts of Europe, as he was dependent on patronage. All

these travels allowed him to embellish his reworking of the old authors in L’histoire

de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, et naifs portraicts,

retirez du naturel (1555). Although his work was generally ignored in his

day due to the dominance of Gessner’s publications - indeed he had been

accused of plagiarism, even though his book appeared in the same year - it was

well regarded by later writers. His classification was derived from Aristotle

and Pliny. Like them, he separated birds on ecological and morphological

principles into raptors, waterfowl with webfeet, fissiped marsh birds (including

kingfishers and bee-eaters), terrestrial birds, large arboreal birds and small

arboreal birds (including swallows). His book was also important for his

attempts to understand anatomy, including a comparison of a human and a bird

skeleton. In addition to his work on birds, Belon wrote on fish, and he was a

keen botanist, with an interest in establishing exotic plant species in France,

to which end he helped establish two botanical gardens. He was working on a

book on plants when he was murdered one night while walking to his home in

Paris.

(1517-1564) travelled widely in Greece, Asia Minor, Egypt and Arabia,

and wrote a popular account of his travels, including natural history (1553).

He lived in various parts of Europe, as he was dependent on patronage. All

these travels allowed him to embellish his reworking of the old authors in L’histoire

de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, et naifs portraicts,

retirez du naturel (1555). Although his work was generally ignored in his

day due to the dominance of Gessner’s publications - indeed he had been

accused of plagiarism, even though his book appeared in the same year - it was

well regarded by later writers. His classification was derived from Aristotle

and Pliny. Like them, he separated birds on ecological and morphological

principles into raptors, waterfowl with webfeet, fissiped marsh birds (including

kingfishers and bee-eaters), terrestrial birds, large arboreal birds and small

arboreal birds (including swallows). His book was also important for his

attempts to understand anatomy, including a comparison of a human and a bird

skeleton. In addition to his work on birds, Belon wrote on fish, and he was a

keen botanist, with an interest in establishing exotic plant species in France,

to which end he helped establish two botanical gardens. He was working on a

book on plants when he was murdered one night while walking to his home in

Paris.

Ulisse

Aldrovandi![]() (1522-1605) had contributed to Gessner’s work but wanted to outdo him,

and produced his encyclopaedic Ornithologia (1599-1603) in three

volumes. In his youth he had been imprisoned as a heretic, as indeed for

various reasons had Gessner, Belon and Coiter; in later life Aldrovandi taught

botany. His first book was a treatise on drugs, which was to be of great use

to later works on pharmacy, but ornithology was his main interest. The

compilation, begun in the 1560s, was the most comprehensive of its kind up to

that time. He criticized Gessner for using an alphabetical arrangement, and

proceeded to follow a classification based on Aristotle. Birds were grouped by

having a hard and powerful beak (raptors, parrots, ravens, woodpeckers,

treecreepers, bee-eaters and crossbills); those that bathe only in dust or in

dust and water (pigeons and buntings); songbirds (finches, larks and canaries);

waterfowl; and shorebirds. As he put everything he could find into his work,

including plagiarizing Gessner and Belon, its real value was sometimes

considered to belong in the earlier works of those authors. He was also

criticized for including few of his own observations. However his work was

judged, it was popular in its day and was continued for other animal groups

after his death in his native Bologna, Italy, by several of his faithful

students.

(1522-1605) had contributed to Gessner’s work but wanted to outdo him,

and produced his encyclopaedic Ornithologia (1599-1603) in three

volumes. In his youth he had been imprisoned as a heretic, as indeed for

various reasons had Gessner, Belon and Coiter; in later life Aldrovandi taught

botany. His first book was a treatise on drugs, which was to be of great use

to later works on pharmacy, but ornithology was his main interest. The

compilation, begun in the 1560s, was the most comprehensive of its kind up to

that time. He criticized Gessner for using an alphabetical arrangement, and

proceeded to follow a classification based on Aristotle. Birds were grouped by

having a hard and powerful beak (raptors, parrots, ravens, woodpeckers,

treecreepers, bee-eaters and crossbills); those that bathe only in dust or in

dust and water (pigeons and buntings); songbirds (finches, larks and canaries);

waterfowl; and shorebirds. As he put everything he could find into his work,

including plagiarizing Gessner and Belon, its real value was sometimes

considered to belong in the earlier works of those authors. He was also

criticized for including few of his own observations. However his work was

judged, it was popular in its day and was continued for other animal groups

after his death in his native Bologna, Italy, by several of his faithful

students.

Volcher

Coiter![]() (1534-1576), born in the Netherlands but spending his working life in

Italy and Germany, was the first person to base a classification of birds on

structure instead of function. He devised a natural system following the

guidelines of Aristotle and Pliny, based on morphology, in De avium

sceletis et praecipuis musculis (1575). The section of this work entitled De

differentiis avium contained the first diagram showing the relationships

of birds. It also summarized his knowledge of the anatomy of birds in an

interpretive way, resembling a key, or perhaps something approaching a

cladogram (see Allen 1951a, 1951b). Although like Pliny he used form (i.e.

morphology) with divisions based on the characters of the feet, his

observations in the text demonstrate their relationships to function. His

subdivisions followed the shape of the claw and the placement of the toes. No

matter how it is viewed, his tabulation represents the beginnings of an

attempt to derive a natural classification of birds based on morphology. In

this way he anticipated the ideal “natural system” envisaged nearly 200

years later by Linnaeus – who had been influenced by the better-known

attempt at a morphological classification a century later by Willughby and Ray.

(1534-1576), born in the Netherlands but spending his working life in

Italy and Germany, was the first person to base a classification of birds on

structure instead of function. He devised a natural system following the

guidelines of Aristotle and Pliny, based on morphology, in De avium

sceletis et praecipuis musculis (1575). The section of this work entitled De

differentiis avium contained the first diagram showing the relationships

of birds. It also summarized his knowledge of the anatomy of birds in an

interpretive way, resembling a key, or perhaps something approaching a

cladogram (see Allen 1951a, 1951b). Although like Pliny he used form (i.e.

morphology) with divisions based on the characters of the feet, his

observations in the text demonstrate their relationships to function. His

subdivisions followed the shape of the claw and the placement of the toes. No

matter how it is viewed, his tabulation represents the beginnings of an

attempt to derive a natural classification of birds based on morphology. In

this way he anticipated the ideal “natural system” envisaged nearly 200

years later by Linnaeus – who had been influenced by the better-known

attempt at a morphological classification a century later by Willughby and Ray.

Caspar Schwenckfeld (1563-1609), in Germany, was a follower of Aristotle and the works of Gessner and Aldrovandi, and made useful observations on the biology of birds. He is the author of the first regional bird list, in Aviarium Silesiae, the fourth volume of his Theriotropheum Silesiae (1603). He provided useful details of about 150 species found in his district, making a valuable early contribution to ornithology. He tried to classify birds according to their habitat, mobility, foot structure, food and colour, but finding these criteria unsatisfactory, he followed Gessner’s alphabetical arrangement. His inclusion of unreliable material from Gessner and Aldrovandi with his original observations represented a trend continued by some later writers.

John Jonston (or Johnstone), also Johannes Johnstonus (1603-1675), a Pole of Scottish descent, produced a compilation on birds from Aldrovandi and other earlier writers, but with nothing original, in his Historiae naturalis de avibus (1650). Its value was in its illustrations, mostly reworking those of Gessner and Aldrovandi but also adding some new ones. It became popular and was widely distributed, translated, printed and used for over a century, last appearing in 1773. Arguably one of the least reliable or original books of the first flowering of modern ornithology became the most popular.

Christopher Merrett (1614-1695) provided the first printed list of British birds, Aves Britannicae, in his Pinax rerum naturalium Britannicarum (1666, reprinted in 1667 because most copies were destroyed in the Great Fire of London). This was later considered by some to be a poor work by an author with little field experience. In classifying the birds, he mostly based his identifications on Aldrovandi and Jonston. Mullens (1908c) reviewed the list of 165 birds, demonstrating Merrett’s attempt to link his identifications with earlier works rather than using his own observations. Even at this late date the bat was still listed amongst birds! Around this time and later in Britain a number of local and county natural histories also appeared. Although such compilations had an earlier history dating back in printed form to at least 1486, their coverage of birds was incidental before Merrett compiled his list (Mullens 1908d). The only one that sought to provide some detail was that of Richard Carew (1555-1620) in his The Survey of Cornwall of 1602 (Mullens 1908b).

Walter Charleton (1619-1707), in his Onomasticon zoicon (1668, revised 1671), sought to provide a systematic classification of all birds. For familiar birds, he based it on Aldrovandi, with two main divisions, of waterbirds and landbirds. Waterbirds were further divided into palmipeds, fissipeds (fish-eaters and insect-eaters) and plant-eaters. Landbirds were further divided into meat-eaters (including bats!), seed-eaters (dust-bathing, dust- and water-bathing, and singing), berry-eaters, and insect-eaters (non-singing and singing). Passerines, like other groups, are scattered amongst these divisions, though mostly in the landbirds. When Charleton had to consider unfamiliar, exotic birds he put them in an appendix under either “Terrestres” or “Aquaticae”. This was the last serious attempt to classify birds following Aristotelian principles. A new system was needed and it was soon to appear.

Francis Willughby (1635-1672) and John Ray (1627-1705), both English clergymen, met at Cambridge, where they developed a plan to record and describe all animals and plants according to their own natural philosophy of the world. Willughby worked most intensively on birds and insects, as well as other animals, and Ray principally on plants. They travelled widely together in Britain and Europe, collecting and recording all they could find. Willughby’s early death from pleurisy left his works unfinished, but he had made financial arrangements for Ray in his will, allowing Ray to edit and publish them (Raven 1942). The Latin Ornithologiae appeared in 1676, followed by a revised edition in English, The Ornithology of Francis Willughby, in 1678. Although the amount of Ray’s contribution to this work has been disputed, the final results obviously benefited from their close collaboration (Mullens 1909b). However the issue is interpreted, this important book founded the beginnings of scientific ornithology. It not only summarized material from older works, with an attempt to separate fact from fiction, but also included much new information; although the main focus was on descriptions of plumage and structure, some details of habits were added. To present this summary of ornithology, a strictly morphological classification was devised, based on beak form, foot structure, and body size. The triumph of form over function, already seen in the then little known work of Coiter, finally replaced the confusion of earlier attempts at creating a natural system of birds. The groupings of species began to resemble bird families recognized today. For example, amongst the passerines, finches, thrushes and crows were placed together.

Ray prepared a new summary of birds in the 1690s but it was still unpublished at the time of his death. As before, new information from the results of recent voyages and travels was added. Two notable collections used were those of Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) from Jamaica (1687-1689) and of Paul Hermann (1640-1695) from India and Ceylon (1672-1680). After Ray’s death, the manuscript was revised by his friend William Derham (1657-1735), who expanded Ray’s coverage of exotic birds by appending a manuscript on the birds of Madras, Avium Maderaspatanarum, the first regional list of Indian birds, which had been passed on to him by James Petiver (1663-1718). At the time, Petiver maintained one of the earliest natural history collections in England and corresponded with potential collectors for both illustrations and specimens of plants and animals. One was Georg Joseph Camel (1661-1706), a Jesuit based in Manila, whose interest in birds resulted in his Observationes de Avibus Philippensibus (1703), the earliest regional paper on Asian birds. The Madras list, from an Edward Buckley, was also incorporated by Derham into Ray’s glossary of foreign bird names and is notable for passerines as the source of the name “pitta”, a local name for “bird”, but subsequently associated with the members of the family Pittidae. This revised summary of The Ornithology appeared in the Synopsis Methodica Avium & Piscium (1713). The original folio of just over 300 pages had been reduced to an octavo, but with additions it still extended to 200 pages. While the natural system of Willughby and Ray was not received favourably by all at the time, it was the most comprehensive and complete of its kind then and for at least another 50 years. It also became an important influence on Linnaeus when he applied his natural system to birds; indeed, he did not improve on it overall.

Johann Ferdinand Adam von Pernau (1660-1731) was interested in the comparative behaviour of birds. He had been influenced by the studies of Schwenkfeld in devising a classification system of birds based on behaviour, but he recognized more categories, and he confined the results of his ideas to his own observations. While he may not have had much success with classification from a systematic perspective, his research produced other valuable results such as the discovery of territory in birds, instinctive behaviour, such as feeding at the nest and why birds migrate, and remarks on the role and meaning of bird song. He elaborated his ideas in his Unterricht, Was mit dem lieblichen Geschöpff, denen Vögeln, auch ausser dem Fang, nur durch Ergründung deren Eigenschafften und Zahmmachung oder anderer Abrichtung man sich vor Lust und Zeitvertreib machen könne (1707, revised 1716, supplement 1720). However, interest in bird behaviour as opposed to systematics, i.e. popular vs scientific ornithology, diverged for about 200 years before the importance of the interrelationships of these aspects of ornithological study was fully appreciated (Fisher 1954; Davis 1994).

Carl Linnaeus![]() (1707-1778), or von Linné

from 1761, disappointed his family by refusing to join the clergy, and he

eventually studied medicine in Uppsala, Sweden, but with a great interest in

botany. In 1735, after adventurous travels in Lapland, he went to the

Netherlands to further his studies. He was already interested in devising a

new system of classification and soon found inspiration from the many

natural-history collections he saw there. He also inspired interest in his

system, with its sequence of Classis, Ordo, Genus, Species and Varietas, and

was sponsored for the publication of the first edition of his Systema

Naturae (1735), then only consisting of several large sheets. His

hierarchical concept of categories of relationship was the real improvement on

Willughby and Ray, who had used Genus in the sense of Aristotle so that it was

interchangeable with the refined Linnaean categories from Class to Genus. Over

the next 20 years, inspired by the work of friends and the fame generated by

the appearance of his simple but useful method, he developed and refined his

natural system. By the sixth edition of Systema Naturae (1748), the

diagnoses of genera and species were much improved. The real inspiration of

Linnaeus was developing a simple but workable system, and this was its great

appeal. For birds he recognized six orders, using the beak and foot as points

of reference: 1. Accipitres (birds of prey, owls, parrots); 2. Picae (woodpeckers,

hornbills, cuckoos, hoopoes, and also crows and crow-like birds); 3. Anseres (swimming

birds); 4. Scolopaces (fissiped waterfowl); 5. Gallinae (ratites, pheasants,

bustards and coots); 6. Passeres (all other passerines, but also pigeons,

hummingbirds, etc.). The old division of landbirds and waterbirds was gone.

The system as we know it today was finally published in the 1750s.

(1707-1778), or von Linné

from 1761, disappointed his family by refusing to join the clergy, and he

eventually studied medicine in Uppsala, Sweden, but with a great interest in

botany. In 1735, after adventurous travels in Lapland, he went to the

Netherlands to further his studies. He was already interested in devising a

new system of classification and soon found inspiration from the many

natural-history collections he saw there. He also inspired interest in his

system, with its sequence of Classis, Ordo, Genus, Species and Varietas, and

was sponsored for the publication of the first edition of his Systema

Naturae (1735), then only consisting of several large sheets. His

hierarchical concept of categories of relationship was the real improvement on

Willughby and Ray, who had used Genus in the sense of Aristotle so that it was

interchangeable with the refined Linnaean categories from Class to Genus. Over

the next 20 years, inspired by the work of friends and the fame generated by

the appearance of his simple but useful method, he developed and refined his

natural system. By the sixth edition of Systema Naturae (1748), the

diagnoses of genera and species were much improved. The real inspiration of

Linnaeus was developing a simple but workable system, and this was its great

appeal. For birds he recognized six orders, using the beak and foot as points

of reference: 1. Accipitres (birds of prey, owls, parrots); 2. Picae (woodpeckers,

hornbills, cuckoos, hoopoes, and also crows and crow-like birds); 3. Anseres (swimming

birds); 4. Scolopaces (fissiped waterfowl); 5. Gallinae (ratites, pheasants,

bustards and coots); 6. Passeres (all other passerines, but also pigeons,

hummingbirds, etc.). The old division of landbirds and waterbirds was gone.

The system as we know it today was finally published in the 1750s.

To some naturalists and zoologists in the mid-eighteenth century the attraction of the Linnaean system was not so much his classification as his strict methodology, which could be varied and played with. Also at this time, several large works illustrating birds in colour but in no particular system became popular. Prominent amongst these were the Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (1731-1743) by Mark Catesby (1682-1749), the first major work on North American birds, and A Natural History of Birds (1743-1751) by George Edwards (1694-1773), both authors enjoying the patronage of Sir Hans Sloane (Feduccia 1985; Mason 1992; McBurney 1997). Pierre Barrère (1690-1755) combined these developments by offering a confusing system in his Ornithologiæ specimen novum…in classes, genera et species, nova methoda, digesta (1745). His approach, mixing large and small birds, worked well as a method for fitting different-sized birds into cabinets! Others, like Barrère, using Linnaeus as the point of reference, could produce different results, such as the Historiae avium prodromus by Jacob Theodor Klein (1685-1759) in 1750, and Avium genera by Paul Heinrich Gerhard Möhring (1710-1792) in 1752, but these publications did not detract from the progress of Linnaeus. Also, collections were increasing in importance (Mearns & Mearns 1998), most famously that of Sir Hans Sloane, willed to the nation on his death in 1753 and forming the genesis of the British Museum, first opened in 1759 (Stearn 1981; MacGregor 1994). The search for a natural system was gaining pace and seemed to be in sight at last.

Per

il seguito dell'interessante relazione

vedere il file PDF![]()

Handbook

of the Birds of the World

The Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW) is a multi-volume series produced by the Spanish publishing house Lynx Edicions. It is the first handbook to cover every living species of bird. The series is edited by Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliott, Jordi Sargatal and David A Christie. So far, 13 volumes have been produced. New volumes appear at annual intervals, and the series is expected to be complete with volume 16 by 2011. When Volume 16 is published, for the first time an animal class will have all the species illustrated and treated in detail in a single work. This has not been done before for any other group in the Animal Kingdom.

Material in each volume is grouped first by family, with an introductory article on each family; this is followed by individual species accounts (taxonomy, subspecies and distribution, descriptive notes, habitat, food and feeding, breeding, movements, status and conservation, bibliography). In addition, all volumes except the first and second contain an essay on a particular ornithological theme. More than 200 renowned specialists and 35 illustrators from more than 40 countries have contributed to the project up to now, as well as 834 photographers from all over the world.

Since the first volume appeared in 1992, the series has received various international awards. The first volume was selected as Bird Book of the Year by the magazines Birdwatch and British Birds, and the fifth volume was recognised as Outstanding Academic Title by Choice Magazine, the American Library Association magazine. The seventh volume, as well as being named Bird Book of the Year by Birdwatch and British Birds, also received the distinction of Best Bird Reference Book in the 2002 WorldTwitch Book Awards. This same distinction was also awarded to Volume 8 a year later in 2003. Individual volumes are large, 32 cm by 25 cm, and weighing between 4-4.6 kg; it has been commented in a review that "fork-lift truck book" would be a better title.

As a complement to the Handbook of the Birds of the World and with the ultimate goal of disseminating knowledge about the world's avifauna, in 2002 Lynx Edicions started the Internet Bird Collection (IBC). It is a free-access, on-line audiovisual library of footage of the world's birds with the aim of posting videos showing a variety of biological aspects (e.g. subspecies, plumages, feeding, breeding, etc.) for every species. It is a non-profit endeavour fuelled by material from more than one hundred contributors from around the world. The IBC currently holds over 32,400 videos representing more than 5,900 species and new material is added daily.

Published

volumes

Volume 1: Ostrich to Ducks

Volume 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl

Volume 3: Hoatzin to Auks

Volume 4: Sandgrouse to Cuckoos

Volume 5: Barn-Owls to Hummingbirds

Volume 6: Mousebirds to Hornbills

Volume 7: Jacamars to Woodpeckers

Volume 8: Broadbills to Tapaculos

Volume 9: Cotingas to Pipits And Wagtails

Volume 10: Cuckoo-Shrikes to Thrushes

Volume 11: Old World Flycatchers to Old World Warblers

Volume 12: Picathartes to Tits and Chickadees

Volume 13: Penduline-tits to Shrikes

Volume 14: Bush-shrikes to Old World Sparrows