Lessico

Sant'Ambrogio

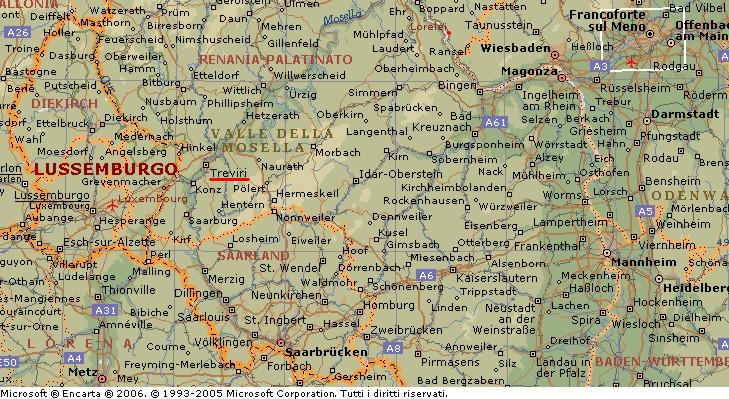

Vescovo e dottore della Chiesa (Treviri 334 o 339/340 - Milano 397). Nato da nobile famiglia romana a Treviri, dove il padre era prefetto della Gallia, fu educato a Roma ed entrò egli pure nella carriera amministrativa dell'impero, divenendo governatore di Liguria ed Emilia con sede a Milano. Lì, mentre era solo catecumeno, alla morte del vescovo Aussenzio, fu dal popolo proclamato suo successore e in breve tempo battezzato e consacrato (7 dicembre 374). E al 7 dicembre ricorre la sua festa.

Rivolse allora alla Chiesa le sue grandi qualità di magistrato. Fu al centro

di gravi contese politiche e religiose: lottò vittoriosamente contro gli

ariani a Milano e nel Concilio di Aquileia![]() (380); si oppose alla restaurazione

di culti pagani a Roma, richiamando l'imperatore Valentiniano II ai suoi

doveri di cristiano, umiliò Teodosio il Grande (colpevole di una spietata

repressione a Tessalonica), che ne divenne poi ammiratore e amico; soccorse in

ogni modo i poveri e gli oppressi. A Milano lo incontrò, nel 386,

Sant'Agostino

(380); si oppose alla restaurazione

di culti pagani a Roma, richiamando l'imperatore Valentiniano II ai suoi

doveri di cristiano, umiliò Teodosio il Grande (colpevole di una spietata

repressione a Tessalonica), che ne divenne poi ammiratore e amico; soccorse in

ogni modo i poveri e gli oppressi. A Milano lo incontrò, nel 386,

Sant'Agostino![]() ,

che ne subì egli pure il potente fascino.

,

che ne subì egli pure il potente fascino.

Infaticabile e illuminato in queste attività di governo, Ambrogio non lo fu meno nelle vesti di oratore e scrittore, sempre rispondendo alle esigenze pastorali della sua posizione. Nella scienza teologica Ambrogio diede un valido contributo all'affermarsi del dogma trinitario, di recente definizione, con la sua terminologia improntata a grande chiarezza e costanza sulle relazioni tra il Padre e il Figlio e sulla processione dello Spirito Santo, superando di gran lunga tutti gli autori ecclesiastici latini e preparando le formule definitive di Sant'Agostino.

Nel problema cristologico, Ambrogio fu il primo a opporsi all'eresia di Apollinare di Laodicea, trovando sulle due nature, unite nella persona del Cristo, espressioni tanto felici da essere adottate dai Concili di Efeso e di Calcedonia. Sant'Agostino inoltre lo cita più volte come fonte autorevole nei problemi più ardui del dogma della grazia: la teoria formulata da Ambrogio sull'origine del male morale nella libera volontà dell'uomo sarà alla base delle speculazioni teologiche del vescovo d'Ippona. Non meno ortodosse e teologicamente valide le sue affermazioni sul valore di sacrificio dell'Eucarestia; nel sacramento della penitenza il vescovo di Milano illustra la penitenza sacramentale, che segue alla confessione segreta dei peccati; nel Battesimo mette in evidenza il valore del Battesimo di desiderio.

Con molto

tatto Ambrogio sa omettere nell'escatologia le esuberanze di Origene![]() e pari

intuito dimostra nell'enunciare le teorie sugli angeli e sul culto dei santi e

delle reliquie. Punto cardine della sua ecclesiologia è l'unità interna

della Chiesa, che egli avverte realizzata solo in una strettissima communio

di tutte le Chiese con la Chiesa romana. Nel campo della morale Ambrogio,

forte di una profonda dottrina e di un non comune senso del diritto, svolse

una vera opera di magistero, flagellando, con l'altezza espressiva di un San

Giovanni Crisostomo, i mali del suo tempo: l'avarizia e la lussuria; opponendo

l'esempio della verginità cristiana e sublimandola a sacrificio soddisfatorio

per i peccati dei molti, dove la visione teologica si apre sul vasto orizzonte

del Corpus Christi Mysticum. Allo zelo infaticabile di Ambrogio pastore

di anime dobbiamo la sua innografia, che trovò presto vastissima diffusione

in tutto l'Occidente: le piccole strofe a quattro righe in metri giambici,

oggettivate in una forma poetica piena di solenne grandezza e nello stesso

tempo facile, limpida e agile, entrarono ben presto nell'uso popolare, perché

“erano fatte apposta per essere popolari”.

e pari

intuito dimostra nell'enunciare le teorie sugli angeli e sul culto dei santi e

delle reliquie. Punto cardine della sua ecclesiologia è l'unità interna

della Chiesa, che egli avverte realizzata solo in una strettissima communio

di tutte le Chiese con la Chiesa romana. Nel campo della morale Ambrogio,

forte di una profonda dottrina e di un non comune senso del diritto, svolse

una vera opera di magistero, flagellando, con l'altezza espressiva di un San

Giovanni Crisostomo, i mali del suo tempo: l'avarizia e la lussuria; opponendo

l'esempio della verginità cristiana e sublimandola a sacrificio soddisfatorio

per i peccati dei molti, dove la visione teologica si apre sul vasto orizzonte

del Corpus Christi Mysticum. Allo zelo infaticabile di Ambrogio pastore

di anime dobbiamo la sua innografia, che trovò presto vastissima diffusione

in tutto l'Occidente: le piccole strofe a quattro righe in metri giambici,

oggettivate in una forma poetica piena di solenne grandezza e nello stesso

tempo facile, limpida e agile, entrarono ben presto nell'uso popolare, perché

“erano fatte apposta per essere popolari”.

Delle sue numerose opere, che testimoniano un'attività infaticabile, citiamo le principali, attenendoci alla divisione tradizionale: Hexaemeron libri sex, De Paradiso, De Abraham libri duo, De Iacob et vita beata libri duo, Enarrationes in XII psalmos davidicos, Expositionis evangelii secundum Lucam libri decem, De officiis ministrorum libri tres, De virginibus, De viduis, De virginitate, De fide ad Gratianum Augustum libri quinque, De Spiritu Sancto, De Incarnationis dominicae sacramento, De paenitentia libri duo, De sacramentis libri sex, Explanatio symboli ad initiandos, Sermo contra Auxentium, De basilicis tradendis, De obitu Theodosii; e vari Inni. Ovunque rifulgono in questi scritti l'equilibrio e il vigore della sua concezione religiosa della vita, in cui quasi si congiungono romanità e cristianesimo.

Aeterne

rerum conditor

Il canto del gallo

|

Aeterne rerum

Conditor, |

Creatore

eterno di tutte le cose, |

|

Nocturna lux viantibus |

Luce notturna ai viandanti, |

|

Hoc excitatus Lucifer |

Destato da quel canto Lucifero |

|

Hoc nauta vires colligit, |

Il navigante riprende forza, |

|

Surgamus ergo strenue: |

Alziamoci dunque con coraggio: |

|

Gallo canente, spes redit, |

Al canto del gallo torna la speranza, |

|

Jesu, labantes respice, |

O Gesù, guarda chi cade, |

|

Tu, lux, refulge sensibus, |

Tu, luce, splendi ai nostri sensi, |

Giustamente

il miele più famoso

è l'Ambrosoli

flash pubblicitario di Andrea Bertolazzi![]()

30 agosto 2006

Sant'Ambrogio

L'imperatore

Teodosio e sant'Ambrogio -1620

di Anton van Dyck (1599-1641)

Ambrogio (Treviri,

339 - Milano, 397), meglio conosciuto come sant'Ambrogio, è venerato come

santo dalla Chiesa cattolica che lo annovera tra i quattro massimi Dottori

della Chiesa insieme a san Girolamo![]() ,

sant'Agostino

,

sant'Agostino![]() e san Gregorio I papa

e san Gregorio I papa![]() .

Assieme a san Carlo Borromeo e san Galdino è patrono della città di Milano,

nella quale è presente una basilica a lui dedicata. In dialetto milanese

viene chiamato Sant Ambroeus (grafia classica) o Sant Ambrös (entrambi

pronunciati sant'ambrœs).

.

Assieme a san Carlo Borromeo e san Galdino è patrono della città di Milano,

nella quale è presente una basilica a lui dedicata. In dialetto milanese

viene chiamato Sant Ambroeus (grafia classica) o Sant Ambrös (entrambi

pronunciati sant'ambrœs).

Ambrogio,

membro di due importanti famiglie senatorie romane (la famiglia Aureliana, da

parte materna, la famiglia Simmaco, da parte paterna), nacque nel 339 a

Treviri (Germania), dove il padre era prefetto del pretorio per la Gallia, ed

essendo destinato alla carriera amministrativa frequentò le migliori scuole

di Roma. Dopo cinque anni di magistratura a Sirmio, nel 370 fu incaricato

quale governatore della Liguria, poi dell'Emilia e, infine, giunse a Milano

come governatore dell'Italia settentrionale. La sua abilità di funzionario

nel dirimere pacificamente i forti contrasti tra ariani![]() e cattolici, gli valse un largo apprezzamento da parte delle due fazioni. Nel

374, alla morte del vescovo ariano Aussenzio di Milano, Ambrogio fu acclamato

vescovo a furor di popolo, anche se non aveva ancora ricevuto il battesimo.

Dopo la conferma della carica da parte dell'imperatore Flavio Valentiniano,

nel giro di una settimana Ambrogio fu battezzato e ricevette il cappello

episcopale.

e cattolici, gli valse un largo apprezzamento da parte delle due fazioni. Nel

374, alla morte del vescovo ariano Aussenzio di Milano, Ambrogio fu acclamato

vescovo a furor di popolo, anche se non aveva ancora ricevuto il battesimo.

Dopo la conferma della carica da parte dell'imperatore Flavio Valentiniano,

nel giro di una settimana Ambrogio fu battezzato e ricevette il cappello

episcopale.

Ambrogio vescovo

Ambrogio, vescovo della città di residenza della corte imperiale, influì positivamente sulla politica religiosa di Teodosio I. Nel 380 con l'editto di Tessalonica il cristianesimo fu proclamato religione di stato. Nel 381 il concilio di Aquileia si pronunciò contro l'arianesimo. Nel 390 intervenne severamente sull'imperatore, che aveva ordinato un massacro tra la popolazione di Tessalonica, rea di aver linciato il capo del presidio romano della città. In tre ore di carneficina erano state assassinate migliaia di persone. Ambrogio impose all'imperatore una penitenza pubblica, cioè l'esclusione dalla partecipazione ai riti sacri. Teodosio accettò il castigo ecclesiale. Nel Natale di quell'anno l'imperatore venne assolto e riammesso ai sacramenti.

Ambrogio

cercò di asservire al potere religioso il potere politico, a volte anche con

espedienti dialettici. Ad esempio, predicava all'imperatore Graziano che le

vittorie non erano dovute all'esercito, ma alla grazia di Dio, da ottenersi

con preghiere e penitenze. Ma, davanti a una grave sconfitta, non esitò a

proclamare che non era il caso di imputarla alla grazia di Dio, ma alla poca

preparazione dell'esercito.

In un altro caso ci furono dei cristiani che (con la partecipazione del

vescovo locale o su istigazione dello stesso) incendiarono la sinagoga di

Callinico (388). Il culto ebraico era del tutto legittimo, e quindi per la

legge romana gli incendiari erano tenuti a ricostruire la sinagoga. Ambrogio

si rifiutò di celebrare una messa davanti all'imperatore Teodosio fin che

questi non solo promise di modificare il decreto ma di annullarlo.

Provvide

anche a impedire che Simmaco![]() (suo amico, e che l'aveva aiutato in altre

circostanze) venisse ricevuto dall'imperatore in quanto delegato del Senato di

Roma. Un imperatore che rifiuta di ricevere il rappresentante del Senato di

Roma a noi pare poca cosa, ma allora suscitò un certo scandalo. Si deve

tuttavia considerare che in quel periodo gli scontri tra gli antichi Senatori

Romani, ancora pagani, e la nuova classe dirigente cristiana, erano frequenti

e di natura per noi difficilmente comprensibile dopo così lunghi anni.

(suo amico, e che l'aveva aiutato in altre

circostanze) venisse ricevuto dall'imperatore in quanto delegato del Senato di

Roma. Un imperatore che rifiuta di ricevere il rappresentante del Senato di

Roma a noi pare poca cosa, ma allora suscitò un certo scandalo. Si deve

tuttavia considerare che in quel periodo gli scontri tra gli antichi Senatori

Romani, ancora pagani, e la nuova classe dirigente cristiana, erano frequenti

e di natura per noi difficilmente comprensibile dopo così lunghi anni.

Rimane aperta la questione sui presunti corpi di martiri che Sant'Ambrogio avrebbe rinvenuto: secondo alcuni si trattava di falsi realizzati ad arte per accrescere il prestigio di Milano, mentre altri li ritengono autentici. La scarsità dei documenti, ovvie implicazioni di fede e la scarsa obiettività delle testimonianze di quel periodo impediscono di dare una risposta certa a tale quesito.

Chiese a Graziano di indire un concilio (che si tenne ad Aquileia nel settembre del 381) per condannare due vescovi eretici, secondo i dettami dei vari concili ecumenici e anche secondo l'opinione del Papa e dei vescovi ortodossi. Graziano avrebbe voluto convocare un concilio più numeroso, ma Ambrogio lo esortò a convocare un numero limitato di vescovi (probabilmente quelli certamente ortodossi) affermando che per appurare la verità bastavano pochi vescovi, e non era il caso di incomodarne troppi, facendo loro affrontare un viaggio faticoso. Dall'altro lato, Ambrogio era una persona che credeva fermamente nel suo operato. La sua porta era sempre aperta, e si prodigava senza tregua per il bene dei cittadini affidati alle sue cure. Si batté strenuamente contro l'arianesimo, giungendo a colpi di mano per occupare le chiese di Milano. La corte imperiale di Milano era apertamente schierata con gli ariani.

Introdusse il canto nella liturgia, e ancor oggi a Milano vi è l'unica scuola che tramanda nei millenni questo antico canto. A lui si deve la conversione di Agostino, che era venuto a Milano per insegnare retorica: Ambrogio e Agostino sono due dei quattro dottori della Chiesa cattolica antica. Fu fautore della supremazia del vescovo di Roma, contro altri vescovi (es. Palladio) che lo ritenevano un vescovo come un altro: da lì a poco il vescovo di Roma Siricio (come già i patriarchi di Costantinopoli e di Antiochia) assumerà il titolo di Papa.

Accanto a queste vicende storiche vi sono delle famose leggende miracolistiche, come quella secondo cui Ambrogio camminando per Milano trovò un fabbro che non riusciva a piegare il morso di un cavallo: in quel morso Ambrogio riconobbe uno dei chiodi con cui venne crocifisso Cristo. Dopo vari passaggi un "chiodo della crocefissione" è tutt'ora appeso nel Duomo di Milano, a grande altezza, sopra l'altar maggiore. La Chiesa Cattolica venera la memoria del santo il 7 dicembre, mentre la Chiesa Ortodossa celebra la sua festa il 20 dicembre.

Rito ambrosiano

Ambrogio introdusse nella chiesa occidentale molti elementi tratti dalle liturgie orientali, in particolare canti e inni. Si attribuisce ad Ambrogio l'inno Te lucis ante, ma la questione è controversa e negata anche da Luigi Biraghi. Le riforme liturgiche furono continuate nella diocesi di Milano anche dai successori e formarono il Rito ambrosiano sopravvissuto alle unificazioni dei riti di papa Gregorio I e del Concilio di Trento.

Sant’Ambrogio e il canto liturgico

Con il termine di ambrosiano non si definisce solo la liturgia della chiesa cattolica che fa riferimento al santo, ma anche un preciso modo di cantare durante la liturgia. Esso viene indicato con il nome di canto ambrosiano. Esso è caratterizzato dal canto di inni, cioè di nuove composizioni poetiche in versi, distinte dai salmi, che vengono cantate da tutti i partecipanti al rito. A differenza di quanto avveniva per i salmi solitamente cantati da un solista o da un gruppo di coristi. Esso viene invece cantato da tutti i partecipanti, in cori alternati, normalmente tra donne e uomini, ma in altri casi tra giovani e anziani o anche tra fanciulli e adulti. Alcuni di questi inni sono stati sicuramente composti da Ambrogio. La certezza viene dal fatto che a menzionarle è Sant’Agostino, che fu discepolo di Sant’Ambrogio. Essi sono:

Aeterne

rerum conditor (cf. Retractionum I,21);

Iam surgit hora tertia (cf. De natura et gratia 63,74);

Deus creator omnium (ricordato nelle Confessioni e citato complessivamente ben

cinque volte dal vescovo di Ippona);

Intende qui regis Israel (cf. Sermo 372 4,3).

Attraverso la liturgia della Chiesa cattolica in generale e di quella ambrosiana in particolare, sono giunti fino a noi una moltitudine di inni in stile ambrosiano. I ricercatori hanno cercato di trovare dei criteri per indicare quelli che, con più certezza, sono stati composti da Ambrogio. Nel 1862 Luigi Biraghi ne indicava tre: la conformità degli inni con l’indole letteraria di Ambrogio, con il suo vocabolario e con il suo stile. Con questi criteri egli arrivò a selezionare diciotto inni:

Splendor

paternae gloriae (nell'aurora)

Iam surgit hora tertia (per l'ora di terza domenicale)

Nunc sancte nobis Spiritus (per l'ora di terza feriale)

Rector potens verax Deus (per l'ora di sesta)

Rerum, Deus, tenax vigor (per l'ora di nona)

Deus creator omnium (per l'ora dell'accensione)

Iesu, corona virginum (inno della verginità)

Intende qui regis Israel (per il Natale del Signore)

Inluminans Altissimus (per le Epifanie del Signore)

Agnes beatae virginis (per sant'Agnese)

Hic est dies versus Dei (per la Pasqua)

Victor, Nabor, Felix, pii (per i santi Vittore, Nabore e Felice)

Grates tibi, Iesu, novas (per i santi Protasio e Gervasio)

Apostolorum passio (per i santi Pietro e Paolo)

Apostolorum supparem (per san Lorenzo)

Amore Christi nobilis (per san Giovanni Evangelista)

Aeterna Christi munera (per i santi martiri)

Aeterne rerum conditor (al canto del gallo)

Gli autori dell’edizione delle opere poetiche di Ambrogio in un volume stampato nel 1994, che ha portato a compimento l’Opera Omnia, in latino e in italiano, del grande vescovo di Milano, hanno ridotto questo numero certo a tredici canti, escludendo quelli per le ore minori, per i martiri e della verginità. L’esclusione va ascritta alla metrica di questi testi. Ambrogio aveva una predilezione per il numero otto. I suoi inni sono tutti di otto strofe con versi ottosillabici. Egli vedeva in questo numero la risurrezione di Cristo, la novità cristiana e la vita eterna, (octava dies, l'ottavo giorno della settimana, cioè il nuovo giorno, in cui inizia l'era del Cristo). Per questi studiosi appare improbabile che egli sia venuto meno a questa preferenza. Quindi quelli di due o di quattro strofe non vengono attribuiti al vescovo milanese.

Per questi autori, non vi è motivo di dubitare che l’autore della melodia sia lo stesso Ambrogio. Per loro natura questi inni nascono consostanziati alla musica. Il Migliavacca nota come Ambrogio possedesse una conoscenza musicale approfondita. Le sue opere rivelano, oltre a una perfetta conoscenza scolastica, anche una particolare propensione musicale. Egli parla dell’arte musicale con cognizione tecnica e non solo con estetica raffinatezza come il suo discepolo Agostino.

Antigiudaismo di Ambrogio

Particolarmente forte fu l'antigiudaismo di Ambrogio: scrive nell'Expositio Evangelii secundum Lucam a proposito del popolo giudaico che esso è: « ...perduto, spirito immondo, preda del diavolo anche all'interno del suo tempio sacro, la sinagoga: anzi la stessa sinagoga è ormai sede e ricettacolo del demonio che stringe entro spire serpentine tutto il popolo giudaico »

Le cronache storiche riportano un episodio rivelatore dell'atteggiamento di Ambrogio nei riguardi degli ebrei. Nel 388, a Callinicum (Kallinikon, sul fiume Eufrate, in Asia, l'attuale Raqqa), una piccola folla di cristiani, guidata dal vescovo locale, diede l'assalto alla sinagoga e la bruciò. Il governatore romano condannò l'accaduto e, per mantenere l'ordine pubblico, diede ordine che la sinagoga venisse ricostruita a spese del vescovo. L'imperatore Teodosio I rese noto di condividere quanto deciso dal suo funzionario. Ambrogio si contrappose alla decisione dell'imperatore: « Il luogo che ospita l’incredulità giudaica sarà ricostruito con le spoglie della Chiesa? Il patrimonio acquistato dai cristiani con la protezione di Cristo sarà trasmesso ai templi degli increduli?... Questa iscrizione porranno i giudei sul frontone della loro sinagoga: - Tempio dell’empietà ricostruito col bottino dei cristiani -... Il popolo giudeo introdurrà questa solennità fra i suoi giorni festivi... »

Ambrogio scrisse allora una lettera a Teodosio per spiegargli che quell'incendio non era affatto un crimine: perché bruciare le sinagoghe era un "atto glorioso" affinché "non possa esserci luogo in cui Dio è negato". Provocatoriamente, egli si assume la responsabilità dell'accaduto. Citando dalla lettera di Ambrogio a Teodosio (tratto da Epistulae 40,11): «...io dichiaro di aver dato alle fiamme la sinagoga, sì, sono stato io che ho dato loro l'incarico, perché non ci sia più nessun luogo dove Cristo venga negato[...]. Che cosa è più importante, il mantenimento dell'ordine o l'interesse della religione? »

Ambrogio non volle salire sull’altare finché l’imperatore non abolì il decreto imperiale riguardante la ricostruzione della sinagoga alle spese del vescovo. Secondo la visione del vescovo, nella questione della religione l'unico foro competente da consultare doveva essere la Chiesa cattolica, la quale grazie ad Ambrogio divenne la religione statale e dominante. In questa impresa lo scopo era quello di avvalorare l’indipendenza della Chiesa dallo Stato, affermando anche la superiorità della Chiesa sullo Stato in quanto emanazione di una legge superiore alla quale tutti devono sottostare.

Sant'Ambrogio non esitava a spezzare i Vasi Sacri e usare il ricavato dalla vendita per il riscatto di prigionieri, disse che in questi casi era lecito spezzare questi Sacri Vasi anche se benedetti.

Opere Esegetiche

Hexaemeron:

raccolta di sei omelie dedicate ai sei giorni della Creazione. Ispirata al

precedente e omonimo lavoro di San Basilio![]() . Le omelie contenute risalgono al

389.

. Le omelie contenute risalgono al

389.

De Paradiso

De Cain et Abel

De Noe

De Abraham

De Isaac et Anima

De Bono Mortis

De Fuga Saeculi

De Jacob et Vita Beata

De Joseph

De Patriarchis

De Helia e Jejunio

De Nabuthae Historia: sulla proprietà, i ricchi e i poveri.

De Tobia

De Interpellatione Job et David

De Apologia Profhetae David

Ennarrationes in XII Psalmos Davidicos

Expositio Psalmi CXVIII

Esposizione del vangelo secondo Luca (composta nel 390).

Expositio Isaiae Prophetae

Opere Dogmatiche

De Fide ad

Gratianum: in tre libri, contiene un avvertimento nei confronti

dell'imperatore Graziano circa l'eresia ariana trattando l'argomento della

Trinità.

De Spiritu Sancto

De Incarnationis Dominicae Sacramento

Explanatio Symboli ad Initiandos

Expositio Fidei

De Mysteriis

De Sacramentis

De Poenitentia (o De Paenitentia)

De Sacramento regenerationis vel de Philosophia: conosciuta solo attraverso

frammenti.

Opere Morali e Ascetiche

De

Officiis Ministrorum: sui doveri dei sacerdoti e sul vivere cristianamente.

De Virginibus

De Viduis

De Virginitate

De Instituitione Virginis

Exhortatio Virginitatis

Curiosità

Due località dell'Alto Milanese sono folcloristicamente legate al Santo:

A Parabiago, secondo una leggenda devozionale, Ambrogio apparve il 21 febbraio 1339, durante la celebre battaglia: a dorso di un cavallo e sguainando una spada, mise paura alla Compagnia di San Giorgio capitanata da Lodrisio Visconti, permettendo alle truppe milanesi del fratello Luchino e del nipote Azzone di vincere. A ricordare tale leggenda fu edificata a Parabiago la Chiesa di Sant'Ambrogio della Vittoria e a Milano su un portone bronzeo del Duomo, gli è stata dedicata una formella.

A Legnano è il patrono del Borgo Sant'Ambrogio, talvolta ricordato con il nome di Burgu du maragàsc (in dialetto legnanese, Borgo di granoturco), che è una delle più antiche tra le otto Contrade che ogni anno partecipano al Palio.

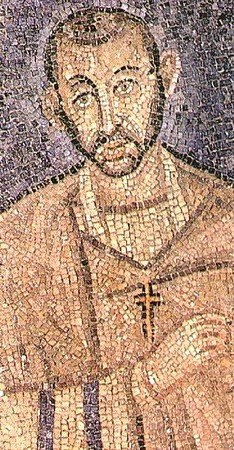

Ambrose

mosaic in the Saint Ambrose Basilic - Milan

Saint Ambrose (c. between 337 and 340 – 4 April 397) was a bishop of Milan who became one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures of the fourth century. He is counted as one of the four original doctors of the Church. Ambrose was born into a Roman Christian family between about 337 and 340 and was raised in Trier. He was the son of a praetorian prefect of Gallia Narbonensis; his mother was a woman of intellect and piety. Ambrose's siblings, Satyrus (who is the subject of Ambrose's De excessu fratris Satyri) and Marcellina, are also venerated as saints. There is a legend that as an infant, a swarm of bees settled on his face while he lay in his cradle, leaving behind a drop of honey. His father considered this a sign of his future eloquence and honeyed tongue. For this reason, bees and beehives often appear in the saint's symbology.

After the early death of his father, Ambrose followed his father's career. He was educated in Rome, studying literature, law, and rhetoric. Praetor Anicius Probus first gave him a place in the council and then in about 372 made him consular prefect of Liguria and Emilia, with headquarters at Milan, which was then beside Rome the second capital in Italy. Ambrose was a governor in northern Italy before he became the Bishop of Milan. Ambrose never married.

Bishop of Milan

In the late 400s there was a deep conflict in the diocese of Milan between the Catholics and Arians. In 374 the bishop of Milan, Auxentius, an Arian, died, and the Arians challenged the succession. Ambrose went to the church where the election was to take place, to prevent an uproar, which was probable in this crisis. His address was interrupted by a call "Ambrose, bishop!", which was taken up by the whole assembly.

Ambrose was known to be personally Catholic, but also acceptable to Arians due to the charity shown in theological matters in this regard. At first he energetically refused the office, for which he was in no way prepared: Ambrose was neither baptized nor formally trained in theology. Upon his appointment, St. Ambrose fled to a colleague's home to seek hiding. Upon receiving a letter from the Emperor praising the appropriateness of Rome appointing individuals evidently worthy of holy positions, St. Ambrose's host gave Ambrose up. Within a week, Ambrose was baptized, ordained and duly installed as bishop of Milan.

As bishop, he immediately adopted an ascetic lifestyle, apportioned his money to the poor, donating all of his land, making only provision for his sister Marcellina, and committed the care of his family to his brother. Saint Ambrose also wrote a treatise by the name of "The Goodness Of Death".

Ambrose and Subordinationists

According to legend, Ambrose immediately and forcefully stopped Arianism in Milan. He moved more realistically and deliberately. In his pursuit of the study of theology with Simplician, a presbyter of Rome he was to excel. Using his excellent knowledge of Greek, which was then rare in the West, to his advantage, he studied the Hebrew Bible and Greek authors like Philo, Origen, Athanasius, and Basil of Caesarea, with whom he was also exchanging letters. He applied this knowledge as preacher, concentrating especially on exegesis of the Old Testament, and his rhetorical abilities impressed Augustine of Hippo, who hitherto had thought poorly of Christian preachers.

In the confrontation with Arians, Ambrose sought to theologically refute their propositions, considered as heretical. The Arians appealed to many high level leaders and clergy in both the Western and Eastern empires. Although the western Emperor Gratian held orthodox belief in the Nicene creed, the younger Valentinian II, who became his colleague in the empire, adhered to the Arian creed. Ambrose did not sway the young prince's position. In the East, Emperor Theodosius I likewise professed the Nicene creed; but there were many adherents of Arianism throughout his dominions, especially among the higher clergy.

In this contested state of religious opinion, two leaders of the Arians, bishops Palladius of Ratiaria and Secundianus of Singidunum, confident of numbers, prevailed upon Gratian to call a general council from all parts of the empire. This request appeared so equitable that he complied without hesitation. However, Ambrose feared the consequences and prevailed upon the emperor to have the matter determined by a council of the Western bishops. Accordingly, a synod composed of thirty-two bishops was held at Aquileia in the year 381. Ambrose was elected president and Palladius, being called upon to defend his opinions, declined. A vote was then taken, when Palladius and his associate Secundianus were deposed from the episcopal office.

Nevertheless, the increasing strength of the Arians proved a formidable task for Ambrose. In 385 or 386 the emperor and his mother Justina, along with a considerable number of clergy and laity, especially military, professed Arianism. They demanded two churches in Milan, one in the city (the basilica of the Apostles), the other in the suburbs (St Victor's), to the Arians. Ambrose refused and was required to answer for his conduct before the council. He went, his eloquence in defence of the Church reportedly overawed the ministers of Emperor Valentinian, so he was permitted to retire without making the surrender of the churches. The day following, when he was performing divine service in the basilica, the prefect of the city came to persuade him to give up at least the Portian basilica in the suburbs. As he still continued obstinate, the court proceeded to violent measures the officers of the household were commanded to prepare the Basilica and the Portian churches to celebrate divine service upon the arrival of the emperor and his mother at the ensuing festival of Easter.

In spite of Imperial opposition, Bishop Ambrose declared: “ If you demand my person, I am ready to submit: carry me to prison or to death, I will not resist; but I will never betray the church of Christ. I will not call upon the people to succour me; I will die at the foot of the altar rather than desert it. The tumult of the people I will not encourage: but God alone can appease it. ”

Ambrose and emperors

The imperial court was displeased with the religious principles of Ambrose, however his aid was soon solicited by the Emperor. When Magnus Maximus usurped the supreme power in Gaul, and was meditating a descent upon Italy, Valentinian sent Ambrose to dissuade him from the undertaking, and the embassy was successful.

On a second attempt of the same kind Ambrose was again employed; and although he was unsuccessful, it cannot be doubted that, if his advice had been followed, the schemes of the usurper would have proved abortive; but the enemy was permitted to enter Italy; and Milan was taken. Justina and her son fled; but Ambrose remained at his post, and did good service to many of the sufferers by causing the plate of the church to be melted for their relief.

Ambrose was equally zealous in combating the attempt made by the upholders of the old state religion to resist the enactments of Christian emperors. The pagan party was led by Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, consul in 391, who presented to Valentinian II a forcible but unsuccessful petition praying for the restoration of the Altar of Victory to its ancient station in the hall of the Roman Senate, the proper support of seven Vestal Virgins, and the regular observance of the other pagan ceremonies.

To this petition Ambrose replied in a letter to Valentinian, arguing that the devoted worshipers of idols had often been forsaken by their deities; that the native valour of the Roman soldiers had gained their victories, and not the pretended influence of pagan priests; that these idolatrous worshipers requested for themselves what they refused to Christians; that voluntary was more honourable than constrained virginity; that as the Christian ministers declined to receive temporal emoluments, they should also be denied to pagan priests; that it was absurd to suppose that God would inflict a famine upon the empire for neglecting to support a religious system contrary to His will as revealed in the Holy Scriptures; that the whole process of nature encouraged innovations, and that all nations had permitted them even in religion; that heathen sacrifices were offensive to Christians; and that it was the duty of a Christian prince to suppress pagan ceremonies. In the epistles of Symmachus and of Ambrose both the petition and the reply are preserved.

To support the logic of his argument, Ambrose halted the celebration of the Eucharist, essentially holding the Christian community hostage, until Theodosius agreed to abort the investigation without requiring reparations to be made by the bishop. Theodosius I, the emperor of the East, espoused the cause of Justina, and regained the kingdom. Theodosius was threatened with excommunication by Ambrose for the massacre of 7,000 persons at Thessalonica in 390, after the murder of the Roman governor there by rioters. Ambrose told Theodosius to imitate David in his repentance as he had imitated him in guilt - Ambrose readmitted the emperor to the Eucharist only after several months of penance . This incident shows the strong position of a bishop in the Western part of the empire, even when facing a strong emperor - the controversy of John Chrysostom with a much weaker emperor a few years later in Constantinople led to a crushing defeat of the bishop. Ambrose's influence upon Theodosius is credited with eliciting the enactment of the "Theodosian decrees" of 391 (see entry Theodosius I).

In 392, after the death of Valentinian II and the acclamation of Eugenius, Ambrose supplicated the emperor for the pardon of those who had supported Eugenius after Theodosius was eventually victorious. Soon after acquiring the undisputed possession of the Roman empire, Theodosius died at Milan in 395, and two years later (April 4, 397) Ambrose also died. He was succeeded as bishop of Milan by Simplician. Ambrose's body may still be viewed in the church of S. Ambrogio in Milan, where it has been continuously venerated — along with the bodies identified in his time as being those of Sts. Gervase and Protase — and is one of the oldest extant bodies of historical personages known outside Egypt.

Character

Many circumstances in the history of Ambrose are characteristic of the general spirit of the times. The chief causes of his victory over his opponents were his great popularity and the reverence paid to the episcopal character at that period. But it must also be noted that he used several indirect means to obtain and support his authority with the people. He was liberal to the poor; it was his custom to comment severely in his preaching on the public characters of his times; and he introduced popular reforms in the order and manner of public worship. It is alleged, too, that at a time when the influence of Ambrose required vigorous support, he was admonished in a dream to search for, and found under the pavement of the church, the remains of two martyrs, Gervasius and Protasius. The saints, although they would have had to have been hundreds of years old, looked as if they had just died. The applause of the people was mingled with the derision of the court party.

Theology

Ambrose ranks with Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory the Great, as one of the Latin Doctors of the Church. Theologians compare him with Hilary, who they claim fell short of Ambrose's administrative excellence but demonstrated greater theological ability. He succeeded as a theologian despite his juridical training and his comparatively late handling of Biblical and doctrinal subjects. His spiritual successor, Augustine, whose conversion was helped by Ambrose's sermons, owes more to him than to any writer except Paul.

Ambrose was a Christian universalist; he believed that all people would eventually achieve salvation. He argued: "Our Savior has appointed two kinds of resurrection in the Apocalypse. 'Blessed is he that hath part in the first resurrection,' for such come to grace without the judgment. As for those who do not come to the first, but are reserved unto the second resurrection, these shall be disciplined until their appointed times, between the first and the second resurrection."

It has been noted that Ambrose's theology was significantly influenced by that of Origen and Didymus the Blind, two other early Christian universalists. Ambrose's intense episcopal consciousness furthered the growing doctrine of the Church and its sacerdotal ministry, while the prevalent asceticism of the day, continuing the Stoic and Ciceronian training of his youth, enabled him to promulgate a lofty standard of Christian ethics. Thus we have the De officiis ministrorum, De viduis, De virginitate and De paenitentia.

Mariology

The powerful mariology of Ambrose of Milan influenced contemporary Popes like Pope Damasus and Siricius and later, Pope Leo the Great. His student Augustine and the Council of Ephesus were equally under his spell. Central to Ambrose is the virginity of Mary and her role as Mother of God.

The virgin birth is worthy of God. Which human birth would have been more worthy of God, than the one, in which the Immaculate Son of God maintained the purity of his immaculate origin while becoming human? We confess, that Christ the Lord was born from a virgin, and therefore we reject the natural order of things. Because not from a man she conceived but from the Holy Spirit. Christ is not divided but one. If we adore him as the Son of God, we do not deny his birth from the virgin... But nobody shall extend this to Mary. Mary was the temple of God but not God in the temple. Therefore only the one who was in the temple can be worshipped. Yes, truly blessed for having surpassed the priest (Zechariah). While the priest denied, the Virgin rectified the error. No wonder that the Lord, wishing to rescue the world, began his work with Mary. Thus she, through whom salvation was being prepared for all people, would be the first to receive the promised fruit of salvation.

Ambrose viewed virginity as superior to marriage and saw Mary as the model of virginity. He is alleged to have founded an institution for virgins in Rome.

Writings

In matters of exegesis he is, like Hilary, an Alexandrian. In dogma he follows Basil of Caesarea and other Greek authors, but nevertheless gives a distinctly Western cast to the speculations of which he treats. This is particularly manifest in the weightier emphasis which he lays upon human sin and divine grace, and in the place which he assigns to faith in the individual Christian life.

De fide ad Gratianum

Augustum (On Faith, to Gratian Augustus)

De officiis (On the Offices of Ministers, an important ecclesiastical handbook)

De Spiritu Sancto (On the Holy Ghost)

De incarnationis Dominicae sacramento (On the Sacrament of the Incarnation of

the Lord)

De mysteriis (On the Mysteries)

Expositio evangelii secundum Lucam (Commentary on the Gospel according to Luke)

Ethical works: De bono mortis (Death as a Good); De fuga saeculi (Flight From the World); De institutione virginis et sanctae Mariae virginitate perpetua ad Eusebium (On the Birth of the Virgin and the Perpetual Virginity of Mary); De Nabuthae (On Naboth); De paenitentia (On Repentance); De paradiso (On Paradise); De sacramentis (On the Sacraments); De viduis (On Widows); De virginibus (On Virgins); De virginitate (On Virginity); Exhortatio virginitatis (Exhortation to Virginity); De sacramento regenerationis sive de philosophia (On the Sacrament of Rebirth, or, On Philosophy [fragments])

Homiletic commentaries on the Old Testament: the Hexaemeron (Six Days of Creation); De Helia et ieiunio (On Elijah and Fasting); De Iacob et vita beata (On Jacob and the Happy Life); De Abraham; De Cain et Abel; De Ioseph (Joseph); De Isaac vel anima (On Isaac, or The Soul); De Noe (Noah); De interpellatione Iob et David (On the Prayer of Job and David); De patriarchis (On the Patriarchs); De Tobia (Tobit); Explanatio psalmorum (Explanation of the Psalms); Explanatio symboli (Commentary on the Symbol).

De obitu Theodosii; De obitu

Valentiniani; De excessu fratris Satyri (funeral orations)

91 letters

A collection of hymns

Fragments of sermons

Ambrosiaster or the "pseudo-Ambrose" is a brief commentary on Paul's

Epistles, which was long attributed to Ambrose.

Church music

Ambrose is traditionally credited but not actually known to have composed any of the repertory of Ambrosian chant also known simply as "chant, a method of chanting, or one side of the choir alternately responding to the other, much as the later pope St. Gregory I the Great is not known to have composed any Gregorian chant, the plainsong or "Romish chant. However, Ambrosian chant was named in his honor due to his contributions to the music of the Church; he is credited with introducing hymnody from the Eastern Church into the West.

Catching the impulse from Hilary and confirmed in it by the success of Arian psalmody, Ambrose composed several original hymns as well, four of which still survive, along with music which may not have changed too much from the original melodies. Each of these hymns has eight four-line stanzas and is written in strict iambic dimeter (that is 2 x 2 iambs). Marked by dignified simplicity, they served as a fruitful model for later times.

Deus Creator Omnium

Aeterne rerum conditor

Jam surgit hora tertia

Jam Christus astra ascendante"

Veni redemptor gentium (a Christmas hymn)

Text of some Ambrosian Hymns

In his writings, Ambrose refers only to the performance of antiphonal psalms, in which solo singing of psalm verses alternated with a congregational refrain called an antiphon. St. Ambrose was also traditionally credited with composing the hymn Te Deum, which he is said to have composed when he baptised Saint Augustine, his celebrated convert.

Ambrose and reading

Ambrose is the subject of a curious anecdote in Augustine's Confessions which bears on the history of reading: “ When [Ambrose] read, his eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still. Anyone could approach him freely and guests were not commonly announced, so that often, when we came to visit him, we found him reading like this in silence, for he never read aloud. ”

This is a celebrated passage in modern scholarly discussion. The practice of reading to oneself without vocalizing the text was less common in antiquity than it has since become. In a culture that set a high value on oratory and public performances of all kinds, in which the production of books was very labor-intensive, the majority of the population was illiterate, and where those with the leisure to enjoy literary works also had slaves to read for them, written texts were more likely to be seen as scripts for recitation than as vehicles of silent reflection. However, there is also abundant evidence that silent reading did occur in antiquity and that it was not usually regarded as unusual.

Ambrose and celibacy

Ambrose is yet again the subject of a curious anecdote in Augustine's Confessions which bears on the history of celibacy: “ Ambrose himself I esteemed a happy man, as the world counted happiness, because great personages held him in honor. Only his celibacy appeared to me a painful burden. ”

Not until the fifth century in the West did celibacy come to be widely regarded as a requirement for all higher ranks of clergy; even then, and for long afterward, the rule was not generally enforced. To make celibacy a condition for full Christian profession by one who did not expect to take holy orders was even more extreme.

Further reading

Hexaemeron, De paradiso, De

Cain, De Noe, De Abraham, De Isaac, De bono mortis – ed. C. Schenkl 1896,

Vol. 32/1

De Iacob, De Ioseph, De patriarchis, De fuga saeculi, De interpellatione Iob

et David, De apologia prophetae David, De Helia, De Nabuthae, De Tobia – ed.

C. Schenkl 1897, Vol. 32/2

Expositio evangelii secundum Lucam – ed. C. Schenkl 1902, Vol. 32/4

Expositio de psalmo CXVIII – ed. M. Petschenig 1913, Vol. 62; editio altera

supplementis aucta – cur. M. Zelzer 1999

Explanatio super psalmos XII – ed. M. Petschenig 1919, Vol. 64; editio

altera supplementis aucta – cur. M. Zelzer 1999

Explanatio symboli, De sacramentis, De mysteriis, De paenitentia, De excessu

fratris Satyri, De obitu Valentiniani, De obitu Theodosii – ed. Otto Faller

1955, Vol. 73

De fide ad Gratianum Augustum – ed. Otto Faller 1962, Vol. 78

De spiritu sancto, De incarnationis dominicae sacramento – ed. Otto Faller

1964, Vol. 79

Epistulae et acta – ed. Otto Faller (Vol. 82/1: lib. 1-6, 1968); Otto Faller,

M. Zelzer ( Vol. 82/2: lib. 7-9, 1982); M. Zelzer ( Vol. 82/3: lib. 10, epp.

extra collectionem. gesta concilii Aquileiensis, 1990); Indices et addenda –

comp. M. Zelzer,

1996, Vol. 82/4

Several of

Ambrose's works have recently been published in the bilingual Latin-German

Fontes Christiani series (currently edited by Brepols).

Several religious brotherhoods which have sprung up in and around Milan at

various times since the 14th century have been called Ambrosians. Their connection to Ambrose

is tenuous.

Émail

sur cuivre par Jacques Laudin (1627-1695)

Collection du musée municipal de Châlons en Champagne

Ambrosius ou Ambroise de Milan (340-397), évêque de Milan de 374 à 397, est l'un des Pères de l'Église latine. Il est connu en tant qu'écrivain et poète, quasi fondateur de l'hymnodie latine chrétienne et lecteur de Cicéron et des Pères grecs, dont il reprend les méthodes d'interprétation allégoriques. Il est aussi l'un des protagonistes des débats contre l'arianisme. C'est auprès de lui que Augustin d'Hippone se convertit au christianisme. Il est honoré comme saint par l'Église orthodoxe et l'Église catholique qui le fête le 7 décembre.

Ambroise serait né à Trèves en 340. Il est le fils d'un Ambrosius, préfet de Rome et deviendra également haut fonctionnaire romain dans l'administration impériale du fils aîné de Constantin. On notera qu'il était le cousin du sénateur Quintus Aurelius Symmaque, Préfet de Rome, contre lequel il écrira une défense du christianisme lorsque Symmaque fera la demande officielle auprès de l'empereur de la restauration de l'Autel de la Victoire dans la Curie.

Selon la Vie d'Ambroise par son secrétaire Paulin de Milan, il aurait été mis en son berceau dans la salle du prétoire. Il y dormait, quand un essaim d'abeilles survint tout a coup et couvrit de telle sorte sa figure et sa bouche qu'il semblait entrer dans sa bouche et en sortir. Les abeilles prirent ensuite leur vol et s'élevèrent en l’air à une telle hauteur que l'œil humain n'était capable de les distinguer. Son père fut frappé de ce fait et dit: « Si ce petit enfant vit, ce sera quelque chose de grand. »

Parvenu à l'adolescence, en voyant sa mère, et sa sœur, qui avaient consacré à Dieu sa virginité, embrasser la main des prêtres, il offrit en se jouant sa droite à sa sœur en l’assurant qu'elle devait en faire autant. Mais elle le lui refusa comme à un enfant et à quelqu'un qui ne sait ce qu'il dit. Après avoir appris les belles lettres à Rome, il plaida avec éclat des causes devant le tribunal, et fut envoyé par l'empereur Valentinien Ier pour prendre le gouvernement des provinces de la Ligurie et de l'Émilie. A Rome il reçoit une éducation qui lui permet de devenir avocat. Puis le préfet du prétoire d'Illyricum, auprès duquel il travaillait à partir de 370, lui confie l'administration de la province de Ligurie-Emilie, dont le siège est à Milan.

En 374 il intervient à ce titre pour rétablir l'ordre lors de l'élection du successeur de l'évêque de tendance arienne, Auxence. Alors qu'il n'est pas encore baptisé, les deux partis le choisissent comme évêque. Son hagiographe raconte l'épisode ainsi: « Il vint à Milan alors que le siège épiscopal était vacant ; le peuple s'assembla pour choisir un évêque: mais une grande sédition s'éleva entre les ariens et les catholiques sur le choix du candidat ; Ambroise y vint pour apaiser la sédition, quand tout à coup se fit entendre la voix d'un enfant qui s'écria: « Ambroise évêque. » Alors à l'unanimité, tous s'accordèrent à acclamer Ambroise évêque. Quand il eut vu cela, afin de détourner l'assemblée de ce choix qu'elle avait fait de lui, il sortit de l’église, monta sur son tribunal et, contre sa coutume, il condamna à des tourments ceux qui étaient accusés. En le voyant agir ainsi, le peuple criait néanmoins: « Que ton péché retombe sur nous. » Alors il fut bouleversé et rentra chez lui. Il voulut faire profession de philosophe: mais afin qu'il ne réussît pas on le fit révoquer. Il fit entrer chez lui publiquement des femmes de mauvaise vie, afin qu'en les voyant le peuple revînt sur son élection ; mais considérant qu'il ne venait pas à ses fins, et que le peuple criait toujours: « Que ton péché retombe sur nous, » il conçut la pensée de prendre la fuite au milieu de la nuit. Et au moment où il se croyait sur le bord du Tessin, il se trouva, le matin, à une porte de Milan, appelée la porte de Rome. Quand on l’eut rencontré, il fut gardé à vue par le peuple. On adressa un rapport au très clément empereur Valentinien, qui apprit avec la plus grande joie qu'on choisissait pour remplir les fonctions du sacerdoce ceux qu'il avait envoyés pour être juges. » Tiré de la Vie d'Ambroise, par Paulin, son secrétaire.

Ambroise a occupé le siège épiscopal de Milan de 374 à 397. Habilement et avec force, il défend les droits de l'Église face à l'Empereur, dont Milan est alors la capitale. Ambroise transféra dans le milieu latin la méditation des Écritures commencée par Origène, en introduisant en Occident la pratique de la Lectio divina.

Œuvres

Ambroise de Milan a composé des hymnes (8 strophes de 4 vers brefs), introduisant en Occident le chant liturgique et lui donnant une forme « officielle ». On continue de chanter les hymnes ambrosiennes dans la liturgie des heures, et de composer des hymnes latines suivant son modèle. On a dit d'Ambroise qu'il était plus un catéchiste qu'un théologien. Il faut souligner qu'il fut un grand connaisseur de la littérature patristique grecque, dont il fit usage dans ses œuvres. Il a produit des écrits doctrinaux, parmi lesquels:

De officiis ministrorum, en 3 livres, ouvrage d'éthique chrétienne (allusion au De officiis de Cicéron), qui aura une grande influence;

De sacramentis, œuvre en quatre livres, des catéchèses pré- et post-baptismales sur les sacrements du baptême, de la confirmation et l’eucharistie ; le 4e livre contient une anaphore;

un traité Des mystères (De mysteriis): catéchèses post-baptismales sur le baptême;

un traité De la foi (c’est-à-dire sur la Trinité ; composé pour Gratien en 376 et 379);

un traité Du Saint Esprit (en 381 ; inspiré de celui de Didyme l’Aveugle, dédié à Gratien);

deux livres Sur la pénitence (vers 384), contre les Novatiens;

une Apologie de David, où il tente d'apaiser le scandale provoqué par l'adultère de David et Bethsabée.

On a également conservé d'Ambroise de Milan des lettres et des oraisons funèbres (de Théodose Ier le Grand, de Valentinien II), ainsi que des sermons sur les Psaumes et des sermons sur la virginité.