Lessico

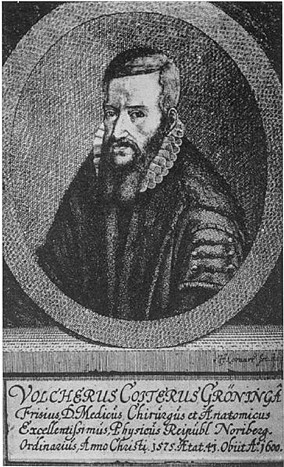

Volcher Coiter

Ulisse

Aldrovandi oltraggiò l'Olanda

eclissando Volcher Coiter

Ulisse

Aldrovandi offended the Netherlands

by eclipsing Volcher Coiter

COITERPULLUS

Il Pulcino di Volcher Coiter - 1564

The Chick of Volcher Coiter - 1564

Anatomista

olandese (Groninga 1534 - Brienne-le-Château,

Champagne-Ardenne, 2 giugno 1576). Coiter si formò

dapprima a Groninga, presso la scuola dell'umanista Regnerus Praedinius (Winsum

1510 - Groningen 1559), le

cui lezioni su Galeno![]() gli fornirono una prima conoscenza della medicina classica. Nel 1555 il

consiglio cittadino gli concesse una borsa di studio per recarsi a studiare

all’estero, presso le più grandi università. Gabriele Falloppio

(1523-1562) a Padova e Bartolomeo Eustachi (ca. 1500/1510-1574) a Roma furono,

in questo periodo, tra i suoi insegnanti.

gli fornirono una prima conoscenza della medicina classica. Nel 1555 il

consiglio cittadino gli concesse una borsa di studio per recarsi a studiare

all’estero, presso le più grandi università. Gabriele Falloppio

(1523-1562) a Padova e Bartolomeo Eustachi (ca. 1500/1510-1574) a Roma furono,

in questo periodo, tra i suoi insegnanti.

Coiter

conseguì il dottorato in medicina a Bologna nel 1562, città in cui poi tenne

lezioni di logica e di chirurgia (comprendenti, queste ultime, anche

l’anatomia). Intorno al 1565-1566 insegnò anatomia a Perugia, quindi fu

incarcerato a Bologna probabilmente per ordine dell’Inquisizione![]() (1566 -

era di

fede protestante), ma il suo nome non compare sia nell'Index librorum

prohibitorum del 1559 che nell'Indice Tridentino del 1564 e del 1596.

(1566 -

era di

fede protestante), ma il suo nome non compare sia nell'Index librorum

prohibitorum del 1559 che nell'Indice Tridentino del 1564 e del 1596.

Coiter passò il resto della vita soprattutto in Germania, dapprima ad Amberg come medico personale di Ludwig VI duca di Baviera, quindi, dal 1569 al 1574, come medico della città di Norimberga. Nel 1575-1576 fu medico militare in Francia, al seguito della spedizione del conte del Palatinato Casimiro in aiuto agli Ugonotti. Morì durante la marcia di ritorno in Germania, forse per tifo.

Il lavoro

di Coiter nel campo dell’anatomia - a parte i primi testi (scarsamente

originali) scritti a Bologna nel periodo del suo insegnamento - rappresenta un

momento decisivo nello sviluppo dell'anatomia rinascimentale. Coiter si

allontanò dalla concezione dell’anatomia umana come era esemplificata

nell'opera di Andrea Vesalio![]() per indirizzarsi verso l'anatomia comparata. Fu incoraggiato in questo da

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605), il quale gli aveva fatto osservare che i

filosofi naturali sono spesso ignoranti e cadono in errore a proposito

dell'anatomia. Coiter sottolineò che la conoscenza anatomica del solo corpo

umano è di per sé sufficiente per i medici, ma non per i filosofi, che

devono invece aver presente le caratteristiche di ogni specie animale.

per indirizzarsi verso l'anatomia comparata. Fu incoraggiato in questo da

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605), il quale gli aveva fatto osservare che i

filosofi naturali sono spesso ignoranti e cadono in errore a proposito

dell'anatomia. Coiter sottolineò che la conoscenza anatomica del solo corpo

umano è di per sé sufficiente per i medici, ma non per i filosofi, che

devono invece aver presente le caratteristiche di ogni specie animale.

La

maggiore autorità nel campo dell’anatomia comparata era Aristotele![]() ;

gran parte del lavoro di Coiter e dei suoi contemporanei fu dedicato proprio

alla verifica dell’attendibilità del filosofo greco, e a riprendere e

sviluppare le sue tecniche di osservazione anatomica.

;

gran parte del lavoro di Coiter e dei suoi contemporanei fu dedicato proprio

alla verifica dell’attendibilità del filosofo greco, e a riprendere e

sviluppare le sue tecniche di osservazione anatomica.

Coiter studiò in modo sistematico la struttura dello scheletro in molti vertebrati e, per mezzo della vivisezione, fu in grado di descrivere forma e funzioni del cuore di serpenti, rane, pesci e gatti, scoprendo fra l’altro come i cuori rescissi dal resto del corpo continuino a battere; studiò inoltre l’anatomia e la struttura scheletrica degli uccelli.

In

embriologia Coiter riprese e perfezionò le osservazioni di Aristotele,

seguendo giorno per giorno lo sviluppo dell’embrione di gallina nell’uovo

(1564)![]() . Come afferma Sandra Tugnoli Pattaro a pagina 10 del suo

"Osservazione di cose straordinarie – Il De observatione foetus in

ovis (1564) di Ulisse Aldrovandi" (Bologna, 2000): "Invero, come

risulta dai documenti, la questione si presenta nei termini seguenti. Sebbene

nell'inedito [De observatione foetus in ovis] e nell'Ornithologia non menzioni collaboratori, Aldrovandi

non effettuò l'indagine in oggetto isolatamente, bensì insieme con un'équipe

di studiosi, entro la quale verosimilmente il ruolo di anatomista venne svolto

precipuamente da Volcher Coiter, ma promotore dell'indagine fu Aldrovandi, suo

maestro."

. Come afferma Sandra Tugnoli Pattaro a pagina 10 del suo

"Osservazione di cose straordinarie – Il De observatione foetus in

ovis (1564) di Ulisse Aldrovandi" (Bologna, 2000): "Invero, come

risulta dai documenti, la questione si presenta nei termini seguenti. Sebbene

nell'inedito [De observatione foetus in ovis] e nell'Ornithologia non menzioni collaboratori, Aldrovandi

non effettuò l'indagine in oggetto isolatamente, bensì insieme con un'équipe

di studiosi, entro la quale verosimilmente il ruolo di anatomista venne svolto

precipuamente da Volcher Coiter, ma promotore dell'indagine fu Aldrovandi, suo

maestro."

Ma

Aldrovandi manco s'è degnato di citare Coiter a proposito dello studio

sull'embrione di pollo. Da vera prima donna, Ulisse esordisce affermando

quotidie unum [ovum] cum maxima diligentia, ac curiositate secui, quotidianamente ho

dissezionato con la massima diligenza e curiosità un uovo![]() . Di Coiter nessuna

traccia.

. Di Coiter nessuna

traccia.

Come

possiamo leggere nella biografia di Coiter stilata da Nicolas Eloy (1778![]() ),

forse qualche voce circolava circa l'arte posseduta da Aldrovandi di approfittarsi degli

altri, di essere un ottimo marpione

),

forse qualche voce circolava circa l'arte posseduta da Aldrovandi di approfittarsi degli

altri, di essere un ottimo marpione![]() : "Il demeura

aussi quelque tems à Bologne, & il disséqua beaucoup d'animaux sous Aldobrandi, habile

Naturaliste qui profita de ses recherches, dont il enrichit ses Ouvrages."

Tradotto

in italiano suona: "Egli rimase pure qualche

tempo a Bologna e sezionò molti animali sotto Aldrovandi, abile naturalista

che approfittò delle sue ricerche con cui arricchì le sue opere." Se

non bastasse, né il

nome né il cognome dell'insigne olandese compaiono nell'elenco degli autori

usati da Aldrovandi nei 3 volumi della sua Ornitologia, elenco che apre

l'inizio del III volume (1603).

Coiter

formulò infine la distinzione tra materia grigia e bianca nel midollo spinale

e osservò i gangli spinali.

: "Il demeura

aussi quelque tems à Bologne, & il disséqua beaucoup d'animaux sous Aldobrandi, habile

Naturaliste qui profita de ses recherches, dont il enrichit ses Ouvrages."

Tradotto

in italiano suona: "Egli rimase pure qualche

tempo a Bologna e sezionò molti animali sotto Aldrovandi, abile naturalista

che approfittò delle sue ricerche con cui arricchì le sue opere." Se

non bastasse, né il

nome né il cognome dell'insigne olandese compaiono nell'elenco degli autori

usati da Aldrovandi nei 3 volumi della sua Ornitologia, elenco che apre

l'inizio del III volume (1603).

Coiter

formulò infine la distinzione tra materia grigia e bianca nel midollo spinale

e osservò i gangli spinali.

Si

dia uno sguardo a questa sezione

Aldrovandi sbolognato - Gessner e Coiter osannati![]()

Scritti di Volcher Coiter

-

Tabulae externarum partium humani corporis, Bologna 1564.

- De ovorum gallinaceorum generationis primo exordio progressusque, et

pulli gallinacei creationis ordine e Analogia ossium humanorum, simiae

et verae et caudatae, quae cynocephali similis est, atque vulpis si

trovano nelle Externarum et internarum principalium humani corporis partium

tabulae ..., Nürnberg 1573.

- De avium sceletis et praecipuis musculis si trova nelle Lectiones

Gabrielis Fallopii ... a Volchero Coitero collectae, Nürnberg 1575.

Volcherus Coiterus popularis magni illius Rodolphi Agricolae fuit, natus Groningae [floruit circa annum 1575], nobili Frisiorum metropoli, cum naturae stimulis ad medicinam elegantiorem ferretur; adeo feliciter in artis ipsius studio et anatomiae exercitio, per Germaniam, Italiam, Galliam versatus est: ut operam eius inclita Norinbergensium res pub honesto stipendio conduxerit. Sed anatomicum celeberrimum immatura mors nobis cito nimis subtraxit. Gallicanam .n. expeditionem secutus, castrensis medicus factus est: ut corporum dissecandorum occasione, abstrusorum morborum abdita et intima, ut sic dicam, penetralia cognosceret. Ibi dum agit, vitam cum artis medicae et anatomicae jactura posuit, medicus et chirurgus felicissimus, circa annum .......

Edidit observationum anatomicarum, medicarum et chirurgicarum miscellanea varia, ex humanis corporibus tam sanis quam male affectis, tam vivis quam mortuis deprompta.

Fallopii item lectiones de partibus similaribus humani corporis, ex diversis exemplaribus collectas: quibus iconas selectorum brutorum in aes incisas adiecit.

Tantillum de hoc medico Germano Io. Schenck. D. in praefat. observationum medicarum de capite humano: bibliothecae variae.

Vitae Germanorum medicorum: qui seculo superiori, et quod excurrit, claruerunt. congestae et ad annum usque mdcxx deductae a Melchiore Adamo. Cum indice triplici: personarum gemino, tertio rerum. - Haidelbergae, Impensis heredum Ionae Rosae, Excudit Iohannes Georgius Geyder, Acad. Typogr. anno mdcxx.

Avian anatomy illustration by Coiter

Volcher Coiter (also spelled Coyter or Koyter) (1534, Groningen - 2 June 1576, Brienne-le-Château) was a Dutch anatomist who established the study of comparative osteology and first described cerebrospinal meningitis.

Coiter was born in Groningen. He studied in Italy and France and was a pupil of Ulisse Aldrovandi, Gabriele Falloppio, Bartolomeo Eustachi and Guillaume Rondelet. He became city physician of Nürnberg in 1569 and later entered military service as field surgeon to Johann Casimir. His works included Externarum et Internarum Principalium Humani Corporis Partium Tabulae (1573) and De Avium Sceletis et Praecipuis Musculis (1575). His work included detailed anatomical studies of birds as well as a classification of the birds based on structure and habits. He produced an early dichotomous classification key.

Coiter’s portrait (1575) in oils, attributed to Nicolas Neufchatel and representing him demonstrating the muscles of the arm, with the écorché he had constructed on his left and a shelf of medical classics behind him, is preserved in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, at Nuremberg; there are later portraits at Weimar and Amsterdam, and there is a copper engraving (1669) by J. F. Leonhart, copies of which are in Nuremberg, Coburg, Copenhagen, and Ithaca, New York.

Coiter, Volcher (b. Groningen, Netherlands, 1534; d. Brienne-le-Château, Champagne-Ardenne, France, 2 June 1576), anatomy, physiology, ornithology, embryology, medicine. Son of a jurist, Coiter was favored with an excellent education in his native city at St. Martin’s school, where the learned Regnerus Praedinius (Winsum 1510 - Groningen 1559) was master; there he first became acquainted with Galen and dissection. His ability was such that in 1555 the city fathers awarded him a stipend for five years of study at foreign universities.

During this period, although dates and movements are not always clear, we know that his good fortune in enjoying eminent teachers continued. He probably studied with Leonhard Fuchs at Tübingen. In 1556 he was briefly at Montpellier; he mentions Guillaume Rondelet and Laurent Joubert, and he also knew Felix Platter. Gabriele Falloppio taught him at Padua, and Bartolomeo Eustachi at Rome. By 1560, and possibly even by 1559, he was at Bologna, where he received the doctorate in medicine on 24 March 1562 and where his researches were guided by Ulisse Aldrovandi and Giulio Cesare Aranzio. At Bologna he lectured on logic and surgery; and at Bologna his first two publications, tables on human anatomy, were issued. For a time he also taught at Perugia.

A brilliant career seemed assured, but letters written in 1566 by his friend Joachim Camerarius the Younger tell of Coiter’s arrest and imprisonment, first in Rome and then in Bologna. It is generally assumed that his Protestantism was responsible and that he offended the Inquisition. By the fall of 1566 he was back in Germany, where Camerarius smoothed the path for him. He served Pfalzgraf Ludwig VI at Amberg and taught there until 1569, when he became physician to the city of Nuremberg.

Documents in Nuremberg and Erlangen, passages in his works, and inscriptions in copies of these works that he presented to friends attest his anatomical and medical activities in Nuremberg and provide details concerning the publication of the treatises which appeared in that city. Bodies of criminals furnished opportunities for dissection, and his daily medical practice fostered an attention to pathology. Among physicians he associated not only with Camerarius but also with Georg Palm, Heinrich Wolff, Melchior Ayrer, Franz Renner, and Thomas Erastus of Heidelberg and Basel. On more than one occasion he had sharp brushes with barber surgeons and quacks. The eminent families Imhof and Kress were served by him. He often traveled outside Nuremberg to treat magisterial, noble, and ecclesiastical patients.

Coiter’s longest excursion from Nuremberg took place from the fall of 1575 to the spring of 1576, when he attended Pfalzgraf Johann Casimir on his expedition to France in support of the Huguenot cause. Coiter did not return from this journey; his death was the result not of military action but of illness, possibly typhus, after peace had been declared and the army was returning to Germany. He left a widow, Helena, who was a foreigner and who was granted permission to remain in Nuremberg two years longer without citizenship.

In a short life of forty-two years Coiter effected significant advances in biological knowledge. His early works on human anatomy were expressly intended for students, as he himself states and as their tabular form favors. In them he still adheres to Galenic doctrine, and they have no essential significance for the history of anatomy. The treatises published at Nuremberg, however, display a greater maturity; a realization that dissection is the most important part of anatomy (both normal and pathological); an appreciation of the work of Vesalius (of whose contributions to anatomy he said, “Incomparabili industria stupendoque ingenio, hanc artem omnibus quasi suis numeris absoluit” - “With incomparable industry and amazing genius he perfected this art in almost every respect.”), Falloppio (notes on whose lectures he published in 1575), and Eustachi; and original thought. The treatise on the skeleton of the fetus and of a child six months old points up the differences between these and adult skeletons and shows where ossification begins.

With a solid grounding in human (especially skeletal) anatomy, Coiter was well prepared for exploration in comparative anatomy. He covered almost the entire vertebrate series — amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals — and was the first to raise this field to independent status in biology, although he emphasized points of difference from human anatomy rather than points of similarity. He recorded what he saw in the living hearts of cats, reptiles, frogs, and several fishes. He called attention to the orbicular muscle of the hedgehog and described the poison gland of the adder and also depicted its skeleton. Coiter’s investigation of avian anatomy is particularly significant: he depicted the skeletons of the crane, the starling, the cormorant, and the parrot; provided a general classification, in tabular form, of the birds known to him; and discovered the tongue and hypobranchial apparatus of the woodpecker.

Coiter knew the value of good drawings and himself signed most of the finely drawn copper engravings that illustrate his anatomical work. Case histories are provided in the interesting miscellany of anatomical and surgical observations, and in these for the first time Coiter described the spinal ganglia and the musculus corrugator supercilii. An interest in anatomical nomenclature and etymology and in balneology is often apparent in his works.

Unillustrated but nonetheless epochal are Coiter’s studies on the development of the chick, begun in Bologna with the encouragement of Aldrovandi and published in Nuremberg; based on observations made on twenty successive days, they presented the first systematic statement since the three-period description (after three days of incubation, after ten, after twenty) provided by Aristotle two millennia before. Coiter worked without a lens but also without Scholastic influence: “There is no futile quarreling over trifles, no pompous arguments, no theoretical bias, and, except for a few references to Aristotle, Lactantius, Columella and Albertus no appeal to authority, but simply a calm, dispassionate, impartial and concise record of his observations with implicit confidence that the truth with prevail” (Howard Adelmann, 1933). Twenty-eight years later (1600) Aldrovandi published his account; Girolamo Fabrizio followed in his posthumous work of 1621, Nathaniel Highmore and William Harvey in 1651, and Marcello Malpighi in 1673 and 1675.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tabulae externarum partium humani corporis (Bologna, 1564) is included, with some changes, in the Externarum et internarum principalium humani corporis partium tabulae, as is, in revised form, De ossibus, et cartilaginibus corporis humani tabulae (Bologna, 1566).

Externarum et internarum principalium humani corporis partium tabulae (Nuremberg, 1572, 1573) contains “Introductio in anatomiam,” “Externarum humani corporis partium tabulae,” “Internarum humani corporis partium tabulae,” “De ovorum gallinaceorum generations primo exordio progressuque, et pulli gallinacei creationis ordine” (trans. and ed. with notes and intro. by Howard B. Adelmann, in Annals of Medical History, n.s. 5 [1933], 327–341, 444–457; trans. and analyzed seriatim at many points, listed in the index, in Adelmann’s Marcello Malpighi and the Evolution of Embryology, 5 vols. [Ithaca, N.Y., 1966]), “Tabulae ossium humani corporis,” “Ossium tum humani foetus adhuc in utero existentis, vel imperfecti abortus, tum infantis dimidium annum nati brevis historia atque explicatio” (also in Hendrik Eysson, Tractatus anatomicus & medicus, De ossibus infantis, cognoscendis, conservandis, & curandis [Groningen, 1659], pp. 169–201; and, after Eysson, in Daniel Le Clere and Jean Jacques Manget, Bibliotheca anatomica [Geneva], 2 [1699], 509–512), “Analogia ossium humanorum, simiae, et verae, et caudatae, quae cynocephali similis est, atque vulpis,” “Tabulae oculorum humanorum,” “De auditus instrumento,” and “Observationum anatomicarum chirurgicarumque miscellanea varia, ex humanis corporibus… deprompta,” Lectiones Gabrielis Fallopii de partibus similaribus, ex diversis exemplaribus a Volchero Coiter… collectae. His accessere diversorum animalium sceletorum explications, iconibus…illustratae…autore eodem Volcher Coiter, (Nuremberg, 1575) has appended to it to the treatise “De avium sceletis et praecipuis musculis.”

Extensive selections from the published works, with English translation, are furnished in Volcher Coiter B. W. Th. Nuyens and A. Schierbeek, eds., no. 18 of Opuscula Selecta Neerlandicorum de Arte Medica (Amsterdam, 1955). Herrlinger (1952) published, from MSS in Nuremberg, Coiter’s “Gutachten zur Sondersiechenschaui” and “Ein ordenttlich Regiementt wie man sich im Wildt Badt haltten sol.” His “Vom rechten Gebrauch dess Carls Padt bei Ellenbogen” appeared in the Anzeiger of the Germanisches Nationl museum (1891), 10–18.

Dorothy

M. Schullian

www.encyclopedia.com

English

translation by Elly Vogelaar![]()

Volcher Coiter (1534-'76) was een wetenschapsman van groot formaat, die voor ons land verloren is gegaan. Geboren te Groningen, werd hij aldaar in de eerste beginselen der geneeskunde ingewijd door de rector van het gymnasium, Praedinius (1510-'59).

Met een jaarlijkse toelage van 20 Embder guldens, welke de stad hem toekende, vertrok Coiter in 1555 naar het buitenland voor zijn studie in de geneeskunde. Hij bezocht de universiteiten te Leuven, Montpellier en Padua, en tenslotte die te Bologna, waar hij in 1561 of in het voorjaar van 1562 de doctorsgraad behaalde. Zijn grote belangstelling voor de ontleedkunde dreef hem vervolgens naar Rome, waar hij de vermaarde Eustachius (1520-'74) hoorde. Voor de vergelijkende anatomie begaf hij zich waarschijnlijk opnieuw naar Montpellier, waar de bekende Rondelet (1507-'66) zich in het door hem gebouwde theater op dit vak toelegde.

Hierna keerde Coiter naar Italië terug en diende hij waarschijnlijk Gabriël Fallopius (1523-62) als prosector. In 1564 werd hij te Bologna tot hoogleraar in de anatomie en chirurgie benoemd (zulke benoemingen golden veelal slechts voor één of enkele jaren). Vermoedelijk is hij in deze jaren tot het protestantisme overgegaan; in elk geval werd hij in 1566 door de Inquisitie van zijn bed gelicht en geboeid naar Rome gevoerd waar hij een jaar in gevangenschap doorbracht. Na zijn vrijlating verliet hij begrijpelijkerwijs Italië, doch keerde niet naar Groningen terug. Hij begaf zich naar Duitsland, was gedurende korte tijd lijfarts van hertog Lodewijk van Beieren, om in 1567 tot zijn voldoening benoemd te worden tot stadsgeneesheer van Neurenberg. Hij overleed in 1576 te Dieu-Ville (bij Reims) tijdens een veldtocht, welke paltsgraaf Johan Casimir ondernomen had om de Hugenoten in Frankrijk bij te staan.

Reeds in

zijn Italiaanse tijd gaf Coiter, blijkbaar ten dienste van het onderwijs,

platenatlassen uit over de uitwendige delen van het lichaam![]() .

In Neurenberg bewerkte hij een fraaie topografische atlas van het menselijk

lichaam, welke in 1573 uitkwam

.

In Neurenberg bewerkte hij een fraaie topografische atlas van het menselijk

lichaam, welke in 1573 uitkwam![]() .

Ook over de ontwikkeling van het ei en de anatomie van de menselijke foetus

deed hij uitstekende waarnemingen. Coiter behoort ongetwijfeld tot de meest

begaafde ontleedkundigen, welke ons land heeft voortgebracht. Doordat hij

voornamelijk in Italië en Duitsland heeft gewerkt, zijn de resultaten van

zijn studies echter niet in het geheel van de Nederlandse medische wetenschap

ingevoegd: Banga bespreekt hem zelfs in het geheel niet. Overigens heeft

Coiter tijdens zijn leven in de wetenschappelijke wereld ook niet de erkenning

gevonden waar hij recht op had

.

Ook over de ontwikkeling van het ei en de anatomie van de menselijke foetus

deed hij uitstekende waarnemingen. Coiter behoort ongetwijfeld tot de meest

begaafde ontleedkundigen, welke ons land heeft voortgebracht. Doordat hij

voornamelijk in Italië en Duitsland heeft gewerkt, zijn de resultaten van

zijn studies echter niet in het geheel van de Nederlandse medische wetenschap

ingevoegd: Banga bespreekt hem zelfs in het geheel niet. Overigens heeft

Coiter tijdens zijn leven in de wetenschappelijke wereld ook niet de erkenning

gevonden waar hij recht op had![]() .

.

13. V. Coiter, Tabulae externarum partium humani corporis. Bologna 1564; De ossibus et cartilaginibus corporis partium Tabulae, ibid. 1566.

14. V. Coiter, Externarum et internarum principalium humani corporis partium Tabulae. Neurenberg 1572.

15. see Coiter: Opusc. XVIII.

www.dbnl.org

Volcher Coiter (1534-'76) was a great scientist, who was unfortunately lost for our country. Born in Groningen, he was thought there the first principles of medicine by the rector of the gymnasium, Praedinius (1510-'59).

With an annual allowance of 20 Embder guilders, which the city granted him, Coiter departed in 1555 to go abroad for his studies in medicine. He visited the universities of Leuven, Montpellier and Padua, and finally that in Bologna, where he had in 1561, or in the spring of 1562 the doctor's degree. His great interest in anatomy drove him to Rome, where he heard form the famous Eustatius (1520-'74). Probably for the comparative anatomy he returned to Montpellier, where the famous Rondelet (1507-'66) (who built the famous theater) was also specialized in anatomy.

Later Coiter returned to Italy and he in all probability served Gabriel Fallopius (1523-62) as prosector. In 1564 he was appointed professor at Bologna in anatomy and surgery (such appointments were usually only one or a few years). Presumably in these years he converted to Protestantism. In any case, he was arrested in1566 by the Inquisition and in chains transported to Rome where he was in captivity for a year. After his release he understandably left Italy, but not turned back to Groningen. He went to Germany, was for a short time personal physician of Duke Louis of Bavaria, in 1567 to his satisfaction to be appointed city physician of Nuremberg. He died in 1576 at Dieu-Ville (in Reims) during a crusade, organised by the palatine Johan Casimir to assist the Huguenots in France.

Already

in his Italian time Coiter, apparently at the service of education, published

several drawings of the outside parts of the body![]() . In

Nuremberg he worked a nice topographical atlas of the human body, which was

released in 1572

. In

Nuremberg he worked a nice topographical atlas of the human body, which was

released in 1572![]() . Also

on the development of the egg and the anatomy of the human fetus, he did

excellent observations.

. Also

on the development of the egg and the anatomy of the human fetus, he did

excellent observations.

Coiter

is undoubtedly the most gifted anatomist, which our country has produced.

Being primarily in Italy and Germany, not all of the results of his studies,

however, are added to the Dutch medical science: Banga even discuss him at

all. Moreover, Coiter during his life in the scientific world never has

received the recognition hat he deserved![]() .

.

1. V. Coiter, Tabulae externarum partium humani corporis. Bologna 1564; De ossibus et cartilaginibus corporis partium Tabulae, ibid. 1566.

2. V. Coiter, Externarum et internarum principalium humani corporis partium Tabulae. Neurenberg 1572.

3. see Coiter: Opusc. XVIII

Volcher Coiter (ou Coyter ou Koyter), né en 1534 à Groningen et mort le 1576 en France, un médecin et naturaliste néerlandais. Pupille d'Aldrovandi, on connaît peu de chose de la vie de Coiter sinon qu'il s'intéresse à l'anatomie et la physiologie. Il est possible qu'il ait étudié auprès de Leonhart Fuchs à Tübingen.

Entre 1562 et 1566, il enseigne la logique et la chirurgie à Bologne où, auparavant, il avait suivi les cours d'Ulisse Aldrovandi. En 1566, il est arrêté par l'Inquisition pour s'être converti à la Réforme et reste emprisonné pendant un an. Entre 1566 et 1569, il sert le margrave Louis VI du Palatinat à Amberg. De 1569 à 1576, il est médecin à Nuremberg. Il est probable que c'est Rudolf Jakob Camerarius qui lui trouve ce poste. En 1575, le margrave l'embauche comme médecin durant une campagne militaire contre la France, campagne durant laquelle il meurt.

Ses observations sur le développement de l'embryon du poulet sont célèbres: il en décrit l'évolution, jour après jour, jusqu'à l'éclosion. Il décrit les organes génitaux de la femme dans Externarum et Internarum Principalium Humani Corporis de 1573. Il fait l'observation que des portions de tissu du cœur fraîchement prélevées continuaient à battre durant un certain temps. Il constate aussi que ce sont les parties à la base du cœur qui battent le plus longtemps. Il est sans doute le premier à décrire ce phénomène.

Il est le premier à faire de l'embryologie une discipline à part entière. Coiter étudie beaucoup l'anatomie des oiseaux et publie de bons dessins des squelettes de grue, de cormoran, de perroquet et de pic vert. Ses écrits montrent que Coiter connaît bien le comportement des oiseaux.

Dictionnaire

historique

de la médecine ancienne et moderne

par Nicolas François Joseph Eloy

Mons – 1778