Lessico

Riti

misterici

Opertanea sacra

A lato delle cerimonie e delle feste della religione pubblica, esistevano delle cerimonie e delle feste che si svolgevano in forma segreta: i misteri. Con il termine misteri (dal greco mystërion, poi in latino mysterium) si suole indicare i culti di carattere esoterico che affondano le loro radici nelle antiche iniziazioni primitive e che si diffusero in tutto il mondo antico greco e medio-orientale, con un particolare sviluppo in etŕ ellenistica e successivamente romana. Esoterico risulta dal greco esřterikós, interiore, derivato da ésř, dentro, tramite il latino esotericus. L'aggettivo si riferisce alle dottrine riservate a una ristretta cerchia di iniziati e all'insegnamento di tali dottrine.

L'etimologia del vocabolo misterico risalirebbe a una radice indoeuropea mu-, che aveva il significato di origine onomatopeica di chiudere la bocca (da cui deriva per esempio il termine muto). Da questa radice sarebbero derivati i termini greci mýř (essere chiuso, chiudersi, iniziare ai misteri), mýësis (iniziazione) e mýstës (iniziato).

Una delle caratteristiche fondamentali, condivisa dalle religioni misteriche, consiste nel fatto che l'insieme delle credenze, delle pratiche religiose e la loro vera natura sono rivelate esclusivamente agli iniziati che hanno l'obbligo di non profanare il segreto, che deve rimanere ineffabile, quindi coperto, nascosto, opertus in latino, da cui opertanea sacra, i riti segreti.

Lexicon

totius latinitatis - 1771

di Egidio Forcellini (1688-1768)![]()

Componenti comuni dei riti misterici sono generalmente simboli sacri e cerimonie magiche, sacramenti e rituali di purificazione, che possono includere sacrifici, abluzioni, digiuni o astinenze, banchetti sacri, danze, ecc.

Altra caratteristica principale delle religioni di mistero č quella di avere carattere salvifico. L'azione iniziatica č destinata a realizzare una realtŕ liberatrice offerta al singolo in risposta ai problemi esistenziali concernenti la vita e la morte. Attraverso vari stadi di iniziazione gli adepti pervengono alla visione beatifica della divinitŕ, che, essendo morta e rinata, garantisce loro la salvezza ultraterrena.

La genesi e lo sviluppo storico delle religioni misteriche č avvenuto prevalentemente in ambito agricolo, nel quale il ciclo vita-morte-rinascita trova il fondamento nell'analogia del ritmo stagionale della vegetazione con la sorte dell'uomo che rinasce a nuova vita. Attraverso la rappresentazione drammatica, simbolica e spirituale dell'alternanza periodica dei fenomeni naturali, attuata nei riti di iniziazione, i proseliti raggiungono il compimento delle loro esigenze escatologiche e soteriologiche.

I principali culti misterici

I misteri

piů famosi del mondo greco erano senz'altro i misteri eleusini![]() ,

legati al culto di Demetra

,

legati al culto di Demetra![]() e

Persefone

e

Persefone![]() . Accanto

a questi sono da ricordare quelli legati al culto di Dioniso

. Accanto

a questi sono da ricordare quelli legati al culto di Dioniso![]() , a quello

di Orfeo

, a quello

di Orfeo![]() , nei

misteri orfici, a quello del dio frigio Sabazio e i misteri dei Cabiri a

Samotracia.

, nei

misteri orfici, a quello del dio frigio Sabazio e i misteri dei Cabiri a

Samotracia.

Nel

sincretismo religioso tipico dell'etŕ ellenistica e piů tardi romana ebbero

notevole importanza le religioni misteriche di origine orientale. I culti

misterici della grande madre Cibele![]() con Attis

con Attis![]() dall'Asia

minore, quelli di Serapide

dall'Asia

minore, quelli di Serapide![]() , Iside e

Osiride

, Iside e

Osiride![]() della

mitologia egizia, e quelli di Mitra dalla Persia (il dio dei patti, e patto significa il suo

nome, quindi il dio dell'amicizia tra uomini e dell'alleanza tra popoli) permearono la facies

religiosa della cultura romana imperiale, che vide il proliferare di templi,

isei e mitrei in tutto il mondo allora conosciuto.

della

mitologia egizia, e quelli di Mitra dalla Persia (il dio dei patti, e patto significa il suo

nome, quindi il dio dell'amicizia tra uomini e dell'alleanza tra popoli) permearono la facies

religiosa della cultura romana imperiale, che vide il proliferare di templi,

isei e mitrei in tutto il mondo allora conosciuto.

Anche

nella letteratura greca, ellenistica e romana si trovano i riflessi

dell'importanza dei misteri nell'ambito culturale antico. Ne sono prova, tra

gli altri, l'inno omerico a Demetra, gli inni orfici e le Metamorfosi

di Apuleio![]() .

.

La grande diffusione delle religioni misteriche ebbe inoltre non poca influenza sul pensiero filosofico tardo antico, come dimostrano le caratteristiche metafisiche tipiche del neoplatonismo, del neopitagorismo e dello gnosticismo.

Mystery cults, or simply Mysteries, were "religious cults of the Graeco-Roman world, full admission to which was restricted to those who had gone through certain secret initiation rites."

The term 'Mystery' derives from Latin mysterium, from Greek mystërion (usually as the plural mystëria), in this context meaning "secret rite or doctrine." An individual who followed such a 'Mystery' was a mýstës "one who has been initiated," from mýein "to close, shut," a reference to secrecy (closure of "eyes and mouth") or that only initiates were allowed to observe and participate in rituals. Mysteries were often supplements to civic religion, rather than competing alternatives of such, and that is the reason these are referred by many scholars as "mystery cults" rather than religions.

The Mysteries were thus cults in which all religious functions were closed to the non-inducted and for which the inner-working of the cult were kept secret from the general public. Although there are no other formal qualifications, mystery cults were also characterized by their lack of an orthodoxy and scripture. Religions that were practiced in secret only in order to avoid religious persecution are not by default Mysteries.

The old meaning of 'mystery' is also preserved in the expression 'mystery play'. These stage performances of medieval Europe were known as such because the first groups to perform them were the craftsmen guilds, entry to which required an initiation and who zealously protected their trade secrets.

The Mysteries are frequently confused with Gnosticism, perhaps in part because Greek gnosis means "knowledge." The gnosis of Gnosticism is however distinct from the arcanum, the "secret wisdom" of the Mysteries: while the Gnostics hoped to acquire knowledge through divine revelation, the mystery religions presumed to have it, with mýstës of high rank revealing the possessed wisdom to acolytes of lower rank.

The term 'mystery cult' applies to a few of the numerous religious rituals of the eastern Mediterranean of late classical antiquity, including the Eleusinian Mysteries, the Dionysian Mysteries, the Orphic Mysteries and the Mithraic Mysteries. Some of the many divinities that the Romans nominally adopted from other cultures also came to be worshipped in Mysteries, so for instance Egyptian Isis, Thracian/Phrygian Sabazius and Phrygian Cybele.

"Plato, an initiate of one of these sacred orders, was severely criticized because in his writings he revealed to the public many of the secret philosophic principles of the Mysteries." (Hall, Manly P. (1928), The Secret Teachings of all ages, San Francisco: s.p., p. 21)

The Eleusinian Mysteries were initiation ceremonies held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at Eleusis in ancient Greece. Of all the mysteries celebrated in ancient times, these were held to be the ones of greatest importance. These myths and mysteries, begun in the Mycenean period (c. 1500 BC), were a major festival during the Hellenistic era and later spread to Rome.

The rites, cultist worships, and beliefs were kept secret, as initiation was believed to unite the worshipper with the gods and included promises of divine power and rewards in the afterlife. There are many paintings and pieces of pottery that depict various aspects of the Mysteries. Since the Mysteries involved visions and conjuring of an afterlife, some scholars believe that the power and longevity of the Eleusinian Mysteries came from psychedelic agents.

“ For among the many excellent and indeed divine institutions which your Athens has brought forth and contributed to human life, none, in my opinion, is better than those mysteries. For by their means we have been brought out of our barbarous and savage mode of life and educated and refined to a state of civilization; and as the rites are called "initiations," so in very truth we have learned from them the beginnings of life, and have gained the power not only to live happily, but also to die with a better hope. ” — Cicero, Laws II, xiv, 36

Mythology of Demeter and Persephone

The Mysteries seem to be related to a myth concerning Demeter, the goddess of agriculture and fertility as recounted in one of the Homeric Hymns (c. 650 BC). According to the hymn, Demeter's daughter Persephone (also referred to as Kore, "girl") was gathering flowers with friends, when she was seized by Hades, the god of death and the underworld, with the consent of her father Zeus. He took her to his underworld kingdom. Distraught, Demeter searched high and low for her daughter. Because of her distress, and in an effort to coerce Zeus to allow the return of her daughter, she caused a terrible drought in which the people suffered and starved. This would have deprived the gods of sacrifice and worship. As a result of this Zeus relents and allows Persephone to return to her mother.

According to the myth, during her search, Demeter traveled long distances and had many minor adventures along the way. In one instance, she teaches the secrets of agriculture to Triptolemus. Finally, by consulting Zeus, Demeter reunites with her daughter and the earth returns to its former verdure and prosperity: the first spring. Before allowing Persephone to return to her mother, Hades gave her seeds of a pomegranate. As a result, Persephone could not avoid returning to the underworld for part of the year. According to the prevailing version of the myth, Persephone had to remain with Hades for four months while staying above ground with her mother for a similar period. This left her the choice of where to spend the last four months of the year and since she opted to live with Demeter, the end result was eight months of growth and abundance to be followed by four months of no productivity. These periods correspond well with the Mediterranean climate of Ancient Greece. The four months during which Persephone is with Hades correspond to the dry Greek summer, a period during which plants are threatened with drought. After the first rains in the fall, when the seeds are planted, Persephone returns from the Underworld and the cycle of growth begins anew.

The Eleusinian Mysteries probably included a celebration of Persephone's return, for it was also the return of plants and of life to the earth. Persephone had gone into the underworld (underground, like seeds in the winter), then returned to the land of the living: her rebirth is symbolic of the rebirth of all plant life during Spring and, by extension, all life on earth.

The Mysteries

The Mysteries are believed to have begun about 1500 BC, during the Mycenean Age. The lesser mysteries were probably held every year; the greater mysteries only every five years. This cycle continued for about two millennia. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, King Celeus is said to have been one of the first people to learn the secret rites and mysteries of her cult. He was also one of her original priests, along with Diocles, Eumolpos, Polyxeinus and Triptolemus, Celeus' son, who had supposedly learned agriculture from Demeter.

Under Pisistratus of Athens, the Eleusinian Mysteries became pan-Hellenic and pilgrims flocked from Greece and beyond to participate. Around 300 BC, the state took over control of the Mysteries; they were specifically controlled by two families, the Eumolpidae and the Kerykes. This led to a vast increase in the number of initiates. The only requirements for membership were a lack of "blood guilt", meaning having never committed murder, and not being a "barbarian" (unable to speak Greek). Men, women and even slaves were allowed initiation.

Participants

There were four categories of people who participated in the Eleusinian Mysteries:

Priests, priestesses and hierophants.

Initiates, undergoing the ceremony for the first time.

Others who had already participated at least once. They were eligible for the fourth category.

Those who had attained epopteia, who had learned the secrets of the greatest mysteries of Demeter.

Secrets

The outline below is only a capsule summary; much of the concrete information about the Eleusinian Mysteries was never written down. For example, only initiates knew what the kiste, a sacred chest, and the kalathos, a lidded basket, contained. The contents, like so much about the Mysteries, are unknown. However, one researcher writes that this Cista ("kiste") contained a golden mystical serpent, egg, a phallus and possibly also seeds sacred to Demeter.

Greater and Lesser Mysteries

There were two Eleusinian Mysteries, the Greater and the Lesser. According to Thomas Taylor, "the dramatic shows of the Lesser Mysteries occultly signified the miseries of the soul while in subjection to the body, so those of the Greater obscurely intimated, by mystic and splendid visions, the felicity of the soul both here and hereafter, when purified from the defilements of a material nature and constantly elevated to the realities of intellectual [spiritual] vision." And that according to Plato, "the ultimate design of the Mysteries … was to lead us back to the principles from which we descended, … a perfect enjoyment of intellectual [spiritual] good."

The Lesser Mysteries were held in Anthesterion (March) but the exact time was not always fixed and changed occasionally, unlike the Greater Mysteries. The priests purified the candidates for initiation (myesis). They first sacrificed a pig to Demeter then purified themselves.

The Greater Mysteries took place in Boedromion (the first month of the Attic calendar, falling in late Summer) and lasted ten days.

Greater Mysteries

The first act (14th Boedromion) of the Greater Mysteries was the bringing of the sacred objects from Eleusis to the Eleusinion, a temple at the base of the Acropolis.

On 15th Boedromion, called Agyrmos, the hierophants (priests) declared prorrhesis, the start of the rites, and carried out the "Hither the victims" sacrifice (hiereia deuro). The "Seawards initiates" (halade mystai) began in Athens on 16th Boedromion with the celebrants washing themselves in the sea at Phaleron.

On 17th Boedromion, the participants began the Epidauria, a festival for Asklepios named after his main sanctuary at Epidauros. This "festival within a festival" celebrated the hero's arrival at Athens with his daughter Hygieia, and consisted of a procession leading to the Eleusinion, during which the mystai apparently stayed at home, a great sacrifice, and an all-night feast (pannychis).

The procession to Eleusis began at Kerameikos (the Athenian cemetery) on the 19th Boedromion from where the people walked to Eleusis, along what was called the "Sacred Way", swinging branches called bacchoi. At a certain spot along the way, they shouted obscenities in commemoration of Iambe (or Baubo), an old woman who, by cracking dirty jokes, had made Demeter smile as she mourned the loss of her daughter. The procession also shouted "Iakch' o Iakche!," referring to Iacchus, possibly an epithet for Dionysus, or a separate deity, son of Persephone or Demeter.

Upon reaching Eleusis, there was a day of fasting in commemoration of Demeter's fasting while searching for Persephone. The fast was broken while drinking a special drink of barley and pennyroyal, called kykeon. Then on 20th and 21st Boedromion, the initiates entered a great hall called Telesterion; in the center stood the Anaktoron ("palace"), which only the hierophantes could enter, where sacred objects were stored. Here, in the Telesterion, the initiates were shown the sacred relics of Demeter. This was the most secretive part of the Mysteries and those who had been initiated were forbidden to ever speak of the events that took place in the Telesterion. The penalty was death. Athenagoras of Athens claims that it was for this crime (among others) that Diagoras had received the death penalty.

As to the climax of the Mysteries, there are two modern theories. Some hold that the priests were the ones to reveal the visions of the holy night, consisting of a fire that represented the possibility of life after death, and various sacred objects. Others hold this explanation to be insufficient to account for the power and longevity of the Mysteries, and that the experiences must have been internal and mediated by a powerful psychoactive ingredient contained in the kykeon drink. (See "entheogenic theories" below.)

Following this section of the Mysteries was the Pannychis, an all-night feast accompanied by dancing and merriment. The dances took place in the Rharian Field, rumored to be the first spot where grain grew. A bull sacrifice also took place late that night or early the next morning. That day (22nd Boedromion), the initiates honored the dead by pouring libations from special vessels. On 23rd Boedromion, the Mysteries ended and everyone returned home.

End of the Eleusinian Mysteries

In 170 AD, the Temple of Demeter was sacked by the Sarmatians but was rebuilt by Marcus Aurelius. Aurelius was then allowed to become the only lay-person to ever enter the anaktoron. As Christianity gained in popularity in the 4th and 5th centuries, Eleusis' prestige began to fade. Julian was the last emperor to be initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries.

The Roman emperor Theodosius I closed the sanctuaries by decree in 392 AD as part of his effort to suppress Hellenist resistance to the imposition of Christianity as a state religion. The last remnants of the Mysteries were wiped out in 396 AD, when Alaric, King of the Goths, invaded accompanied by Christians "in their dark garments", bringing Arian Christianity and desecrating the old sacred sites. The closing of the Eleusinian Mysteries in the 4th century is reported by Eunapios, a historian and biographer of the Greek philosophers. Eunapios had been initiated by the last legitimate Hierophant, who had been commissioned by the emperor Julian to restore the Mysteries, which had by then fallen into decay. According to Eunapios, the very last Hierophant was a usurper, "the man from Thespiae who held the rank of Father in the mysteries of Mithras."

The Mysteries in art

There are many paintings and pieces of pottery that depict various aspects of the Mysteries. The Eleusinian Relief, from late 5th century BC, displayed in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens is a representative example. Triptolemus is depicted receiving seeds from Demeter and teaching mankind how to work the fields to grow crops, with Persephone holding her hand over his head to protect him. Vases and other works of relief sculpture, from the 4th, 5th and 6th centuries BC, depict Triptolemus holding an ear of corn, sitting on a winged throne or chariot, surrounded by Persephone and Demeter with pine torches.

The Niinnion Tablet, found in the same museum, depicts Demeter, followed by Persephone and Iacchus, and then the procession of initiates. Then, Demeter is sitting on the kiste inside the Telesterion, with Persephone holding a torch and introducing the initiates. The initiates each hold a bacchoi. The second row of initiates were led by Iakchos, a priest who held torches for the ceremonies. He is standing near the omphalos while an unknown female (probably a priestess of Demeter) sat nearby on the kiste, holding a scepter and a vessel filled with kykeon. Pannychis is also represented.

In Shakespeare's The Tempest, the masque that Prospero conjures to celebrate the troth-pledging of Miranda and Ferdinand echoes the Eleusinian Mysteries, although it uses the Roman names for the deities involved - Ceres, Iris, Dis and others - instead of the Greek. It is interesting that a play which is so steeped in esoteric imagery from alchemy and hermeticism should draw on the Mysteries for its central masque sequence.

Entheogenic theories

Some scholars believe that the power of the Eleusinian Mysteries came from the kykeon's functioning as a psychedelic agent. Barley may be parasitized by the fungus ergot, which contains the psychoactive alkaloids lysergic acid amide (LSA), a precursor to LSD and ergonovine. It is possible that a psychoactive potion was created using known methods of the day. The initiates, sensitized by their fast and prepared by preceding ceremonies, may have been propelled by the effects of a powerful psychoactive potion into revelatory mind states with profound spiritual and intellectual ramifications.

While modern scholars have presented evidence supporting their view that a potion was drunk as part of the ceremony, the exact composition of that agent remains controversial. Modern preparations of kykeon using ergot-parasitized barley have yielded inconclusive results, although Alexander Shulgin and Ann Shulgin describe both ergonovine and LSA to be known to produce LSD-like effects. Terence McKenna argued that the mysteries were focused around a variety of Psilocybe mushrooms, and various other entheogenic plants, such as Amanita muscaria mushrooms, have also been suggested but at present no consensus has been reached. The size of the event may rule out Amanita or Psilocybe mushrooms as active ingredient, since it is unlikely that there would have been enough wild mushrooms for all participants. However a recent hypothesis suggests that Psilocybe cultivation technology was not unknown in ancient Egypt, from which it could easily have spread to Greece.

Another theory is that the kykeon was an Ayahuasca analog involving Syrian Rue (Peganum harmala), a shrub which grows throughout the Mediterranean and also functions as a Monoamine oxidase inhibitor. The most likely candidate for the DMT containing plant, of which there are many in nature, would be a species of Acacia. Other scholars however, noting the lack of any solid evidence and stressing the collective rather than individual character of mysteric initiation, regard entheogenic theories with pointed skepticism.

Orphism (more rarely Orphicism) is the name given to a set of religious beliefs and practices in the ancient Greek and Thracian world, associated with literature ascribed to the mythical poet Orpheus, who descended into Hades and returned. Orphics also revered Persephone (who descended into Hades each winter and returned each spring) and Dionysus or Bacchus (who also descended into Hades and returned). Poetry containing distinctly Orphic beliefs has been traced back to the 6th or at least 5th century BC, and graffiti of the 5th century BC apparently refers to "Orphics".

Classical sources refer to "Orpheus-initiators" (Orpheotelestai), and associated rites, although how far "Orphic" literature in general related to these rites is not certain. As in the Eleusinian mysteries, initiation into Orphic mysteries promised advantages in the afterlife.

Peculiarities

According to the Thracian orphism primary there exists the Great Goddess – Mother. She is the Universe: she self conceived and bore to her first-born son, who is the sun during the day and fire during the night, (personified as Zagreus or Sabazius). The main elements of Orphism differed from popular ancient Greek religion in the following ways:

- by characterizing human souls as divine and immortal but doomed to live (for

a period) in a "grievous circle" of successive bodily lives through

metempsychosis or the transmigration of souls.

- by prescribing an ascetic way of life which, together with secret initiation

rites, was supposed to guarantee not only eventual release from the "grievous

circle" but also communion with god(s).

- by warning of postmortem punishment for certain transgressions committed

during life.

- by being founded upon sacred writings about the origin of gods and human

beings.

Evidence

Though distinctively Orphic views and practices are attested as early as Herodotus, Euripides, and Plato, most of the sources to the teachings and practices of Orphism are late and ambiguous, and some scholars have claimed that Orphism is in fact a construction of a later date. However the recently published Derveni papyrus allows Orphic mythology to be dated back to the 4th century BC, and it is probably even older. Other inscriptions found in various parts of the Greek world testify to the early existence of a movement with the same core beliefs that were later associated with the name of Orphism.

Mythology

The Orphic theogonies are genealogical works like the Theogony of Hesiod, but the details are different. They are possibly influenced by Near Eastern models. The main story is this: Dionysus (in his incarnation as Zagreus) is the son of Zeus and Persephone; he is murdered and boiled by the Titans. Zeus hurls a thunderbolt on the Titans, as Hermes snatches Zagreus' heart to safety. The resulting ashes, from which sinful mankind is born, contain the bodies of the Titans and Dionysus. The soul of man (Dionysus factor) is therefore divine, but the body (Titan factor) holds the soul in bondage. It was declared that the soul returned repeatedly to life, bound to the wheel of rebirth.

The heart of Dionysus is implanted into the leg of Zeus; he then makes the mortal woman Semele pregnant with the re-born Dionysus. Many of these details are referred to sporadically in the classical authors.

The "Protogonos Theogony", lost, composed ca. 500 BC which is known through the commentary in the Derveni papyrus and references in classical authors (Empedocles and Pindar).

The "Eudemian Theogony", lost, composed in the 5th cent. BC. It is the product of a syncretic Bacchic-Kouretic cult.

The "Rhapsodic Theogony", lost, composed in the Hellenistic age,

incorporating earlier works. It is known through summaries in later

neo-Platonist authors.

Orphic hymns. 87 hexametric poems of a shorter length composed in the late

Hellenistic or early Roman Imperial age.

Eschatology

The epigraphical sources demonstrate that the "Orphic" mythology about Dionysus' death and resurrection was associated with beliefs in a blessed afterlife. Bone tablets found in Olbia (5th cent. BC) carry short and enigmatic inscriptions like: "Life. Death. Life. Truth. Dio(nysus). Orphics." The function of these bone tablets is unknown.

Gold leaves found in graves from Thurii, Hipponium, Thessaly and Crete (4th cent. BC) give instructions to the dead. When he comes to Hades, he must take care not to drink of Lethe ("Forgetfulness"), but of the pool of Mnemosyne ("Memory"), and he must say to the guards:

"I am the son of Earth and Starry Heaven. I am thirsty, please give me something to drink from the fountain of Mnemosyne."

Other gold leaves say:

"Now you are dead, and now you are born on this very day, thrice blessed. Tell Persephone, that Bacchus himself has redeemed you."

Pythagoreanism

Orphic views and practices have parallels to elements of Pythagoreanism. There is, however, too little evidence to determine the extent to which one movement may have influenced the other.

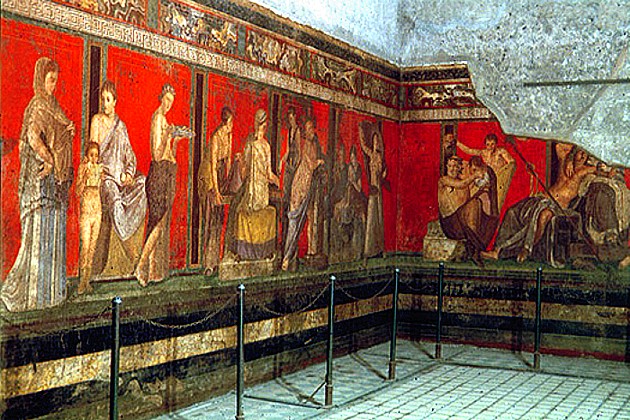

Scenes of a Dionysiac Mystery Cult. Mural Frieze. 50 B.C. Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii

The Dionysian Mysteries probably began as an ancient initiation society, or family of similar societies, centred on a primeval nature god (and his consort), apparently associated with horned animals, serpents and solitary predators (primarily big cats), later known to the Greeks in the eclectic figure of Dionysus. It seems to have first taken organised form in Minoan Crete or Greece between 3000 BCE and 1000 BCE. When absorbed into Greek culture, it gradually evolved into a complex mystery religion that utilized intoxicants and other trance inducing techniques, such as dance and music, to remove inhibitions and artificial societal constraints, liberating the individual to return to a more natural and primal state. It also afforded a degree of liberation for the marginals of Greek society, women, slaves and foreigners.

In their final phase the Mysteries apparently shifted from a chthonic, primeval orientation to a transcendental, mystical one, with Dionysus altering his nature accordingly (much in the same way as happened in the cult of Shiva, Dionysos' eastern counterpart, according to some). Other scholars see these Mysteries, with their resurrected god and secret knowledge about the afterlife, as the precursor of the Eleusinian Mysteries, Orphic Mysteries, Gnosticism and Early Christianity. Manifestations of all its phases are said to have existed in a diverse range of Dionysos cults on the shores of the Mediterranean up until late Roman times.

The mysteries unveiled

Apart from this basic outline the Mysteries remain largely just that, a mystery, as very little knowledge of them has been passed down to us. Our current knowledge is largely based on the speculation of various scholars (notably Carl Kerenyi and W F Otto), drawing on contemporary descriptions and imagery and comparative cross cultural studies.

The sophisticated Dionysian Mysteries of mainland Greece and the Roman Empire are generally thought to have evolved from a more primitive initiatory cult of unknown origin, that had spread throughout the Mediterranean region by the start of the Classical Greek period. Its spread possibly associated with the dissemination of wine, a sacrament or entheogen with which it appears always to have been closely associated (though mead may have been the original sacrament). Beginning as a simple primitive rite it appears to have quickly evolved within Greek culture into a popular Mystery Religion, which absorbed a variety of similar ancient cults, and their parallel gods, in a typically Greek eclectic synthesis across its colonial territories. In one of its late forms it mutated into what some would call the Orphic Mysteries (not to be confused with the more general trend called Orphism). But all stages of this developmental spectrum appear to have continued in parallel in various locales on the shores of the eastern Mediterranean until quite late in pagan history. On integration-individuation theories, read Carl Gustav Jung's "Analytical Psychology" (Princeton: Princeton U Press, 1991).

A brief history of the early Dionysus cult

The ecstatic cult of Dionysus was originally thought to have been a late arrival in Greece from Thrace or Asia Minor, due to the popularity of the cult there and the non integration of Dionysus into the original Olympian Pantheon. But following the identification of the deity's name on Mycenean Linear B tablets this theory has now been abandoned and the cult is accepted as effectively indigenous and predating Greek civilization. The absence of an early Olympian Dionysus is today explained in terms of patterns of social exclusion and the marginality of the cult rather than chronology. The question of whether the cult originated on Minoan Crete, as an aspect of an ancient Zagreus, or in Thrace or Asia as a proto-Sabazius (or even Africa) is still unanswerable given the available evidence. Some believe it was an adopted cult that was not native to any of these places, and may have even been an eclectic cult in its earliest history, though it almost certainly obtained many of its most familiar features from Minoan culture.

The original rite of Dionysus, as introduced into Greece, is almost universally held to have been associated with a "wine cult" (perhaps not too dissimilar to the entheogenic cults of ancient Central America in some ways), concerned with the cultivation of the grapevine, and a practical understanding of its life cycle - which was probably believed to have embodied the living god - as well as the production and fermentation of wine from its dismembered body - apparently associated with the essence of the dead god in the underworld. Most importantly however the intoxicating and disinhibiting effects of the drink itself were once regarded as due to possession by the god's spirit and later as a facilitator of this possession. Some wine was also given as libation to the earth and growing vine, completing the circle. The cult would not only have been solely concerned with the lore of the vine itself, but almost as much with other components of wine.

Wine originally commonly included many other ingredients, herbal, floral and resinous, adding to its quality, flavor and medicinal properties, and was far more diverse than the simple drink we know today. Some scholars have suggested that given the very low alcohol content of early wine its apparent effects were perhaps due to an entheogenic ingredient in its sacred form. Honey and bees wax were also often added to wine, bringing with them the associations of the even older drink mead. Kerenyi in fact postulates that this wine lore superseded and partly absorbed a much earlier Neolithic mead lore, involving the very bee swarms that the Greeks associated with the presence of Dionysus. Mead as well as beer, and its cereal base, were certainly incorporated into the domain of Dionysus at some stage, perhaps via his identification with the wild Thracian corn deity Sabazius. Other plants believed to be viniculturally significant were also included in the retinue of wine lore. Thus were added ivy, once thought to negate the effects of drunkenness, and thus opposite of the grapevine - a symbolic relation also due to its blooming in winter rather than summer; the fig, thought to be a purgative of toxins; and the pine, a wine preservative. Similarly the bull - from whose hollowed horns wine was once drunk - and the goat - whose flesh provided wineskins, as well as acting as a natural 'pruner of the vine', were also included as wine cult animals and according to this theory eventually seen as manifestations of Dionysus. It is likely that some of these associations had long been linked with fertility deities like Dionysus and to a certain extent became reinterpreted in his new role. But an understanding of this vinicultural lore and its symbolic interpretation is crucial to an understanding of the cult that emerged from it, and would take on significance quite apart from wine making that would encompass life, death and rebirth and acquire a deep awareness of human psychology.

If the Dionysus Cult first came to Greece with the importation of wine, as seems likely, then it probably first emerged around 6000 BC in one of two places, either in the Zagros Mountains, the borderlands of Mesopotamia and Persia, both with their own rich wine culture since then (arriving in Europe via Asia Minor), or from the ancient wild vines on the mountain slopes of Libya / North Africa, the source of early Egyptian wine from around 2500 BC, and home of many an ecstatic rite involving animal possession - notably the goat and panther men of the Aissaoua Sufi cult of Morocco (though it is also possible that this was of later origin and influenced by Dionysian cults itself). Whatever the case it appears Minoan Crete was the next link in the chain of transmission, importing wine from the Egyptians, Thracians and Phoenicians and exporting it to its own colonies, such as Greece. Thus it was in Minoan Crete (c. 3000 to 1000 BCE) that the basic Mysteries probably took form — certainly the name Dionysus exists nowhere else other than here and Greece.

The rites were based on a seasonal death-rebirth theme and on spirit possession. The death-rebirth theme is supposedly common to all vegetation cults. The Osirian, for example, closely paralleled the Dionysian, according to contemporary Greek and Egyptian observers. Spirit possession involved an 'atavistic' liberation from the constraints of civilisation and its rules. It was a celebration of all that was outside civilized society and a return to the source of being — something that would later take on mystical connotations. It also involved an escape from the socialized personality and ego either into an ecstatic, deified state or into a primal herd, often both. Dionysus in this sense was the 'beast god' within, or as we moderns might conceive it, and Jung certainly saw it, the unconscious mind. Such activity has been interpreted variously as fertilizing, invigorating, cathartic, liberational and even transformative. Thus it is not surprising that many of the devotees of Dionysus were originally the outsiders of mainstream society: women, slaves, outlaws and foreigners, non-citizens under Greek democracy. All of these were considered equal in a cult that appears often to have transgressively inverted their roles, much like the Roman Saturnalia. In fact in Greece at its height the Dionysian rites were almost entirely associated with women, allegedly liberating themselves from their suppression in Greek society. However, the fact that the titles of the officers of the cult were of male and female gender disproves the once popular claim that the cult was solely a women's mystery.

The trance induction that was central to the cult involved not only chemognosis, but also the 'invocation of spirit' by means of the bull roarer, and ecstatic communal dancing to drum and pipe, much like today's raves. The trances induced are described in terms familiar to anthropologists, with characteristic movements such as the backward head flick, found in all trance inducing cults, and represented most famously today by Afro-American Vodou and its counterparts. And just as in Vodou rites, and the best raves, certain drum rhythms were associated with the trance state. Rhythms are allegedly also found preserved in Greek prose that referred to the Dionysus rites, specifically the Bacchae of Euripides. This compilation of classical quotes describes such ancient rites in the Greek countryside, where they were held high in the mountains to which ritual processions were made on certain feast days:

Following the torches as they dipped and swayed in the darkness, they climbed mountain paths with head thrown back and eyes glazed, dancing to the beat of the drum which stirred their blood' [or 'staggered drunkenly with what was known as the Dionysos gait']. 'In this state of ekstasis or enthusiasmos, they abandoned themselves, dancing wildly and shouting 'Euoi!' [the god's name] and at that moment of intense rapture became identified with the god himself. They became filled with his spirit and acquired divine powers.

This practice is represented in Greek culture by the famous Bacchanals of the Maenads, Thyiades and Bacchoi, and it was no wonder that many Greek rulers considered the cult a threat to civilized society and wished to control it, if not suppress it outright. The latter failing and the former ultimately succeeding in the foundation of a domesticated Dionysianism in the form of a State Religion in Athens! However this was but one form of Dionysianism, a cult that took on many forms in different localities, often absorbing indigenous divinities, and their rites, similar to Dionysus. The Greek Bacchoi claimed that like wine, Dionysus had a different flavour in different regions, reflecting their mythical and cultural soil, their Terroir, and appeared under different names and manners in different regions. On remote Greek islands and the barbarous fringes of Thrace and Macedonia, or so it was rumored, the most primeval forms of Dionysianism continued to be practised, some of which still included human sacrifice as late as the Roman period. A taste of the nature of the primal Dionysos might be more readily accessible to modern readers when we consider that when the Macedonian Greeks reached India under Alexander and his heirs, they claimed Dionysos had gone ahead of them, in the form of a local deity known to us as Shiva. Bactrian coins were minted with both gods on either side, and strangely the two gods would evolve along similar lines.

Dionysus in this most bestial aspect is believed to preserve the archaic archetype of the "Lord of the Animals", and to a certain extent also the ambiguous "Trickster" archetype. His ritual procession of Maenads and Bacchoi was portrayed as heralded by a troop of panthers or tigers, sileni, and satyrs, often led by Pan himself.

The ritualized atavism of Dionysos was also associated with a 'descent into the underworld' of which Dionysos was also regarded as lord; thus Hades and Dionysos are one and the same, declared Heraclitus a philosopher closely associated with the Mysteries according to some commentators.

The emergence and evolution of the Dionysian Mysteries

The idea of a mystery religion was essentially of a series of initiations which benefited the individual or their society in some way. Initially associated with the passage from childhood to adulthood and maturity, they later became seen as what we might call an evolutionary rite. And it was in the form of a Mystery Religion that the Dionysus Cult was first channeled in a more civilized way, probably first in Minoan Crete.

The notion behind the Dionysian Mysteries seems to have been of not only the affirmation of the primeval bestial side of mankind, but its mastery and integration into a civilized psychology and social culture. Given the dual role of Ariadne as the Mistress of the Minoan Labyrinth and consort of Dionysus, some have seen the Minotaur story as also partly deriving from the idea of the mastery of mankind's animal nature, though this remains controversial. The self mastery achieved on this way was not one of domination as in similar cults, most famously preserved in contemporary culture as George and the Dragon, and perhaps the original Minotaur myth, but one of acceptance and integration. Thus while the Mysteries did much to lighten the darker aspects of the Cult they often failed to reassure its perhaps excessively civilized critics and continued to be regarded by many as dangerously liberative (particularly given its egalitarian tendencies as well).

In Athens, atavistic possession was also channeled into dramatic masked ritual within the Bacchic Thiasos (Greek equivalent of a 'coven' or 'lodge'), seeding the emergence of acting and theatre, crafts also sacred to Dionysos, particularly in the form of tragedy and comedy. Thus the Dionysian Mysteries came to be seen as not only as a recognition and casting off the repressive over civilised masks we all wear, and the realisation our true nature, but with the creation of new more authentic masks as well, arguably also the deeper function of drama and comedy too. In other words the development of genuine character rather than socialised persona. In time as Dionysos became regarded as less bestial and more mystical, with the general shift of Pagan orientation, this also came to be seen as the generation of a soul and the survival of death. Themes that would become central to the later Orphic manifestations of Dionysianism that would influence early Christianity according to Roman commentators, denounced as devlilsh mockery of Christ by Justin Martyr (Dialogue with Trypho ch. 64).

The basic ritual that accomplished this appear to have been for men the identification with the god Dionysos in a ritual enactment of his myth of life, death and rebirth, including some form of ordeal. This involved a ritualised descent into the underworld or katabasis, apparently often carried out in actual caverns or catacombs, though sometimes more symbolically in temples. This process always seems to have been a part of the rites, and one form of it may be preserved in Aristophanes play, the Frogs (405 BC), which features the descent of Dionysos into Hades, with the assistance of a surreal chorus of amphibian guardians, and the advice of his half-brother Heracles, who also appears in the iconography of the Dionysian Mysteries. In these narratives someone or something is sought after and brought back, with varying degrees of success, the details vary. However, in Classical Greek culture this probably involved more theatre, with the initiate acting the role of the Heroes, than the full possession of the original rites. Following this there was usually a communion with the god through shared wine. The Initiate was then afterwards known as a Bacchoi, or Bacchus, the alternative name for Dionysos, shown the secret contents of the Liknon or Arc and presented with the thyrsos wand. In contrast the female initiate was prepared as a bride of Dionysos, an Ariadne, and encountered him in union in the underworld. In reference to this the ritual symbol of Dionysos hidden in the Arc till the culmination of the female rites was said to be a goat's penis and later fig wood phallus. After which she undertook a similar communion or wedding feast. Flagellation also seems to have been a basic ordeal, at least for women, according to many depictions of Dionysian initiations, and there are indications of some sort of ritualised hanging. All of this would have taken place at the same time as the traditional Dionysian revelries.

The evolution of Dionysianism continued in the Roman Empire, with the Bacchic Mysteries, as they were known in Italy after their arrival in 200 BC. Here Dionysos was merged with the local fertility god Liber, whose consort Libera was the inspiration for the statue of liberty, a principle she and her partner also represented. The Roman Bacchic Cult typically emphasised the sexual aspects of the religion, and invented terrifying, chthonic ordeals for its Mystery initiation. It was this aspect that led to the cults banning by the Roman authorities in 186 BC, for alleged sexual abuse and other criminal activities, including accusations of murder. Whether these charges were true or not is uncertain, there may have been individual cases of corruption as in any institution, but there is no evidence of widespread corruption, and the general opinion is that these were trumped up charges levelled against a cult seen as a danger to the State. The Roman Senate thus sought to ban the Dionysian rites throughout the Empire, and restricted their gatherings to no more than a handful of people under special licence in Rome. However, this was never fully successful and only succeeded in pushing the cult underground. They gained even more infamy due to the claims that the wife and inspirer of Spartacus, leader of the Slave Revolt of 73 BC, was an initiate of the Thracian Mysteries of Dionysos, who considered her husband an incarnation of Dionysos Liber. But they were revived in a slightly tamer form under Julius Caesar around 50 BC, with his one time ally Mark Anthony becoming an enthusiastic devotee, and gaining much popular support in the process. They remained in existence, along with their carnivalesque Bacchanalian street processions, until at least the time of Augustine (A.D 354-430) and were implanted in most Romanised provinces.

Although much scholarship in these studies, like so much of ancient history, is based on educated guesswork, we do have some insight into the female initiation process through the murals of the Bacchic Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii. Here a series of murals painted on the walls of an initiation chamber have been almost perfectly preserved after the eruption of Vesuvius, though there remains controversy as to whether the entire process is shown and how it should be interpreted.

The first mural shows a noble Roman woman approaching a priestess or matron seated on a throne, by which stands a small boy reading a scroll. This is presumably the declaration of the initiation. On the other side of the throne the initiate is shown again, in a purple robe and myrtle crown, holding a sprig of laurel, and a tray of cakes. She appears to have been transformed into a serving girl.

The second mural depicts another priestess, or senior initiate, and her assistants preparing the Liknon basket, at her feet are mysterious mushroom shaped objects, which some find suggestive. To one side a sileni (a horse elemental) is generating musical ambiance on a lyre.

The third mural shows a satyr playing the panpipes and a nymph suckling a goat in an Arcadian scene. To their right the initiate is shown in a state of panic. This is the last time we see her when she appears again she has undergone a change that is not shown. Some scholars think a katabasis occurs now, others disagree.

In the direction in which she stares in horror, another mural shows a young Satyr being offered a bowl of something (probably wine) by a Silenus, while behind him another Satyr holds up a bestial mask, which the drinking satyr seems to see reflected in the bowl. This may parallel the mirror into which a young Dionysos stares in the Orphic rites. Next to them sits an enthroned goddess (Ariadne or Semele) with Bacchus lying erotically across her lap.

The next mural sees the initiate returning, she now carries a staff and wears a cap, items often presented after the successful completion of an ordeal. She kneels before the priestess and then appears to be whipped by a winged female figure. Flagellation may have been one of the many trance control techniques used in the Bacchic rites. Next to her is a dancing figure, a Maenad or Thyiad.

In her penultimate appearance we see her being prepared with new clothes, while an Eros holds up a mirror to her.

Finally she is shown enthroned and in a wedding costume. The last mural after this is merely an image of Eros. This is all we definitely know of the Roman rites of initiation.

The Mystery rites

The Dionysian Mysteries are believed to have consisted of two sets of rites, the secret rites of initiation just outlined and the outer public, or Dionysia The public rites are generally held to be the most ancient of the two.

The public rites

In Athens and the Attica of the Classical period the main festivities were held in the month of Elaphebolion (around the time of the Spring Equinox) where the Greater, or City, Dionysia had evolved into a great drama festival — Dionysos having become the god of acting, music and poetic inspiration for the Athenians - as well as an urban carnival or Komos. Its older precursor had been demoted to the Lesser, or Rural, Dionysia, though preserved more ancient customs centred on a celebration of the first wine. This festival was timed to coincide with the "clearing of the wine", a final stage in the fermentation process occurring in the first cold snap after the Winter Solstice, when it was declared Dionysos was reborn. This was later formalised to January 6 (now Epiphany), a day on which water was also turned to wine by Dionysos in a separate myth. The festivals at this time were much wilder too, as were the festivities of the grape harvest, and its carnivalesque ritual processions from the vineyards to the wine press, which had occurred earlier in the autumn. It was at these times that initiations into the Mysteries were probably originally held.

Dionysos was also revered at Delphi, where he presided over the oracle for three winter months, beginning in November, marked by the rising of the Pleiades, while Apollo was away "visiting the Hyperboreans". At this time a rite of known as the "Dance of the Fiery Stars" was performed, of which little is known, but appears to have been appropriation of the dead, which was continued in Christian countries as All Souls Day on November 2.

In sharp contrast to the daytime festivities of the Athenian Dionysia were the biennial nocturnal rites of the Tristeria, held on Mount Parnassus in the Winter. These celebrated the emergence of Dionysos from the underworld, with wild orgies in the mountains. The first day of which was presided over by the Maenads, in their state of Mainomenos, or madness, in which an extreme atavistic state was achieved, during which animals were hunted - and, in some lurid tales, even human beings - before being torn apart with bare hands and eaten raw (this being the infamous "Sparagmos", said to have been once associated with goat sacrifice, marking the harvesting and trampling of the vine). The second day saw the Bacchic Nymphs in their Thyiadic, or raving, state, a more sensual and benign Bacchanal assisted by satyrs, though still orgiastic. The mythographers would explain this with claims that the Maenads, or wild women, were the resisters of the Bacchic urge, sent mad, while the Thyiades, or ravers, had accepted the Dionysiac ecstasy and kept their sanity. This has some plausibility in terms of psychological repression, though sceptics claim the Maenad stories may have been exaggerations to scare away the curious tourist!

While the Athenians celebrated Dionysos in various day festivals, including those during the Eleusinian Mysteries, a far older tradition was the two year cycle, where for a whole year the death and absence of Dionysos was mourned, in his aspect of Dionysos Chthonios, Lord of the Underworld. Followed by a second year in which his resurrection as Dionysos Bacchos, was celebrated at the Tristeria and other festivities, including one marked by the rising of Sirius). Why this unusual period was adopted is uncertain, though it may have reflected a long fermentation period. All the most ancient Dionysian rites reflected stages in the wine production process. It was only later that the Athenians and others synchronised the Bacchic festivities with the common agricultural seasons.

The first large scale religious worship of Dionysos in Greece seems to have begun in Thebes in around 1500 BC, around a thousand years before the development of the Athenian Mysteries. Here a cult worship of Dionysos, and his mother Semele, a Moon goddess, was performed in the earliest Dionysian temples, usually located in the liminal spaces beyond the walls of the city, on the edges of swamps and marshes. Its first rituals were probably similar to those ancient rites still held on Greek islands, such as Keos and Tenedos, even in Classical times, but which probably originated in the Mycenaean period. Here the first wine was offered to Dionysos, and to the now growing vine, and a bull was sacrificed with a double axe, its blood mixed with the wine. There are indications that at one time the sacrificer of the sacred bull was himself then stoned to death, though this became a mere symbolic act quite early on in most places. The more economical practise of goat sacrifice seems to have been added to the rites later. The goat, like the bull, being regarded as a manifestation of Dionysos, but was also seen as the 'killer of the vine', due to its tendency to consume it, welcome in times of pruning, but unwelcome in times of growth. The death of the goat could thus be interpreted as a combined Dionysos sacrifice and the vengeful slaying of the sacrificer. It was usually torn apart, just as the vine had been at the harvest. Other archaic rites found on the Greek islands include festivals to his consort, Ariadne, which included some form of tree swinging game, said to date to a time when Ariadne hung herself from a tree. Some see a remnant of ritual hanging or partial asphyxiation in these games.

In Rome the Bacchanalia, essentially a milder form of the Tristeria, were held in secret and originally attended by women only, on three days in the year in the grove of Simila near the Aventine Hill, on March 16 and 17. Subsequently, admission to the rites were re-opened to men and celebrations took place five times a month! Initiation could take place at any of these times.

Within these public rituals were hidden the secret rites of initiation, the public festivals largely setting the ambiance for these private rites, as A E Waite evocatively puts it, perhaps getting a little carried away:

"Whatsoever may have remained to represent the original intent of the rites, regarded as Rites of Initiation, the externalities and practice of the Festivals were orgies of wine and sex: there was every kind of drunkenness and every aberration of sex, the one leading up to the other. Over all reigned the Phallus, which - in its symbolism a rebours - represented post ejaculation the death-state of Bacchus, the god of pleasure, and his resurrection when it was in forma errecta. Of such was the sorrow and of such the joy of these Mysteries". (A E Waite, New Encyclopaedia of Freemasonry)

Whatever we make of Waite's interesting interpretation, the phallus does appear to have been a connecting link between the outer and inner rites. Not only was it prominent in the Bacchic carnival in Rome, carried by the Phallophoroi at the head of the procession; it also appears to have been the secret object in the Liknon, the sacred basket, or Arc, revealed only to initiates after their final initiation. Other possible contents could have been sacred fruit or leaves, or alternatively loafs, possibly with entheogenic qualities, with some scholars speculatively combining these possibilities in imaginative ways. Some sources suggest that the phallus used was made from fig wood (see Prosymnus), while even older sources indicate it may have once been the phallus of the sacrificed goat. Indeed the contents probably changed over the centuries and in different modes of initiation, the general idea being that the final stage of the initiation involved the revelation of the god in one form or another.

The temple and its officers

The sacred loci of the Dionysian Mysteries have varied over time and place, just like the rites themselves. The earliest rites took place in the wilderness - in the forests and woods, the marshes, and particularly high in the mountains, where the lower oxygen content was suitable for trance induction. Later the 'priest' would simply cast their staff into the ground, at any suitable location, and hang a mask and an animal skin from it, the circle drawn around this centre becoming the sacred precinct for however long the staff remained. This practise soon became archaic, but was apparently revived by the nomadic healers of the Orphic Mysteries. In Classical times dedicated temples were built for Dionysos, the earliest being circular buildings open to the sky - probably the origin of Greek theatres and forums, the later no different to any other Greek temple as Dionysos was gradually assimilated. The Lenos, or the building that contained the wine press, also became a temple to Bacchus, and was often solely used as such. Underground chambers were also often used for initiations, which may have originally taken place in natural caves, particularly those by the shoreline. Liminal boundary zones being especially sacred to Dionysos. By the final days of the cult however any temple could be dedicated or rededicated to Dionysos.

Most Mystery Religions had a hierarchy of priests maintaining them, but it is uncertain if this was the case with the Dionysian Mysteries. The Orphic texts of the late period record a boukolos, or 'cowherd', as an offerer of sacrifice, sayer of prayers, and hymn singer, who seems to have been the nearest thing they ever had to a priest. Other inscriptions record an archiboukolos, or 'chief cowherd' presiding over these boukoloi, and in some records there is also mention of boukoloi hieroi, 'holy cowherders' as well as hymnodidaskaloi,'hymn teachers'. According to Athenian sources, where the Dionysos Cult was State controlled, over all of these was placed a High Priest, or Hierophant, as well as a High Priestess, later referred to in Rome as the Matrona, who had two 'assistant priestesses'. One late text even describes a complex hierarchy of three archiboukoloi, seven boukoloi hieroi and eleven boukoloi. The personal names of many of the senior priests and priestesses reveal them to be aristocrats, though the high priest in at least one text has the name of a slave, indicating the supposed equality within the cult, where slaves and masters were encouraged to exchange roles. Curiously there is no evidence of such a complex hierarchy in the Bacchic Mysteries of Rome, which seem to have been simply presided over by a Domina and Dominus, serving as a High Priestess and Priest, and so it is possible that only the established Athenian form of the Mysteries and the Orphic Religion had this structure. The original Mysteries of Dionysos seem to have had no real hierarchy at all, as only ritual functionaries, such as the Phallophoroi, are mentioned, the rest being participant Bacchoi, Thyiades or Maenads. However, a key role was always reserved for the Heroes, and his 'bride', who were possessed by the god, and initiates may have played officiating roles in this process.

Ritual miscellanies

Dionysian paraphernalia

The Kantharos, a drinking cup with large handles, originally the Rhyton, a drinking horn (from a bull), and later a Kylix, or wine goblet; the Thyrsos, a long wand with a pine cone on top, carried by initiates, and those possessed by the god; the Stave, once cast into ground to mark ritual space; the Krater, or mixing bowl, the Flagellum, or scourge; the Minoan Double Axe, once used for sacrificial rites, later replaced by the Greek Kopis, or curved dagger; the Retis, the hunter's net; the Laurel Crown and Cloak (purple robe, or leopard or fawn skin nebix); the Hunting Boots; the Persona or Masks; the Bull Roarer; the Salpinx, a long straight trumpet, the Pan Pipes, Tympanon, Bells and Drums; the Liknon, the sacred basket; with the Fig.

Traditional offerings to Dionysos

Musk, civet, frankincense, storax, ivy, grapes, pine, fig, wine, honey, apples,

Indian Hemp, orchis root, thistle, all wild and domestic trees, black

diamonds.

Animals sacred to Dionysos

The Bull and Goat, and their 'enemies' the Panther (or any big cat, after the Greeks colonised part of India Shiva's Tiger sometimes replaced traditional Panthers or Leopards) and the Serpent (probably largely from Sabazius, but also found in North African cults). Also the Fawn / Deer, the Fox, the Wolf, the Bear, the Dolphin, Bees and all Dragons.

An invocation of Dionysos, from the Orphic hymns

"I call upon loud-roaring and revelling Dionysos,

primeval, double-natured, thrice-born, Bacchic lord,

wild, ineffable, secretive, two-horned and two-shaped.

Ivy-covered, bull-faced, warlike, howling, pure,

You take raw flesh, you have feasts, wrapt in foliage, decked with grape

clusters.

Resourceful Eubouleus, immortal god sired by Zeus

When he mated with Persephone in unspeakable union.

Hearken to my voice, O blessed one,

and with your fair-girdled nymphs breathe on me in a spirit of perfect

agape."

"In intoxication, physical or spiritual, the initiate recovers an intensity of feeling which prudence had destroyed; he finds the world full of delight and beauty, and his imagination is suddenly liberated from the prison of everyday preoccupations. The Bacchic ritual produced what was called 'enthusiasm', which means etymologically having the god enter the worshipper, who believed that he became one with the god." (Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy).

Double-faced

Mithraic relief. Rome, second to third century CE. Louvre Museum.

Front:Mithras killing the bull, being looked over by the Sun god and the Moon

god.

Back: Mithras banquetting with the Sun god.

The Mithraic Mysteries or Mysteries of Mithras (also Mithraism) was a mystery religion practised in the Roman Empire (1st to 4th centuries CE), best attested in Rome and Ostia, Mauretania, Britain and in the provinces along the Rhine and Danube frontier.

Rituals and worship

Mithraism was an initiatory order, passed from initiate to initiate, like the Eleusinian Mysteries. It was not based on a body of scripture, and hence very little written documentary evidence survives. Soldiers and the lower nobility appeared to be the most plentiful followers of Mithraism. Until recently, women were generally thought to not have been allowed to join, but it has now been suggested that "women were involved with Mithraic groups in at least some locations of the empire." Recently revealed discrepancies such as these suggest that Mithraic beliefs were (contra the older supposition) not internally consistent and monolithic, but rather, varied from location to location.

No Mithraic scripture or first-hand account of its highly secret rituals survives, with the possible exception of a liturgy recorded in a 4th century papyrus, thought to be an atypical representation of the cult at best. Current knowledge of the mysteries is almost entirely limited to what can be deduced from the iconography in the mithraea that have survived.

Religious practice was centered around the mithraeum (Latin, from Greek mithraion), either an adapted natural cave or cavern or an artificial building imitating a cavern. Mithraea were dark and windowless, even if they were not actually in a subterranean space or in a natural cave. When possible, the mithraeum was constructed within or below an existing building. The site of a mithraeum may also be identified by its separate entrance or vestibule, its "cave", called the spelaeum or spelunca, with raised benches along the side walls for the ritual meal, and its sanctuary at the far end, often in a recess, before which the pedestal-like altar stood. Many mithraea that follow this basic plan are scattered over much of the Empire's former area, particularly where the legions were stationed along the frontiers (such as Britain). Others may be recognized by their characteristic layout, even though converted as crypts beneath Christian churches.

From the structure of the mithraea it is possible to surmise that worshippers would have gathered for a common meal along the reclining couches lining the walls. Most temples could hold only thirty or forty individuals.

The mithraeum itself was arranged as an "image of the universe". It is noticed by some researchers that this movement, especially in the context of mithraic iconography (see below), seems to stem from the neoplatonic concept that the "running" of the sun from solstice to solstice is a parallel for the movement of the soul through the universe, from pre-existence, into the body, and then beyond the physical body into an afterlife.

Mithraic ranks

The members of a mithraeum were divided into seven ranks. All members were expected to progress through the first four ranks, while only a few would go on to the three higher ranks. The first four ranks represent spiritual progress—the new initiate became a Corax, while the Leo was an adept—the other three have been specialized offices. The seven ranks were:

Corax (raven)

Nymphus (bridegroom)

Miles (soldier)

Leo (lion)

Perses (Persian)

Heliodromus (sun-courier)

Pater (father)

The titles of the first four ranks suggest the possibility that advancement through the ranks was based on introspection and spiritual growth.

The tauroctony

In every Mithraic temple, the place of honor was occupied by a tauroctony, a representation of Mithras killing a sacred bull which was associated with spring. Mithras is depicted as an energetic young man, wearing a Phrygian cap, a short tunic that flares at the hem, pants and a cloak which furls out behind him. Mithras grasps the bull so as to force it into submission, with his knee on its back and one hand forcing back its head while he stabs it in the neck with a short sword. The figure of Mithras is usually shown at a diagonal angle and with the face turned forward. The representations occur as both reliefs, and as three-dimensional sculpture; however the three dimensional images have a strongly frontal aspect.

A serpent and a dog seem to drink from the bull's open wound which is sometimes depicted as spilling grain rather than blood, and a scorpion (usually interpreted as a sign for autumn) attacks the bull's testicles sapping the bull for strength. Sometimes, a raven or crow is also present, and sometimes also a goblet and small lion. Cautes and Cautopates, the celestial twins of light and darkness, are torch-bearers, standing on either side with their legs crossed, Cautes with his brand pointing up and Cautopates with his turned down. Above Mithras, the symbols for Sol and Luna are present in the starry night sky.

The Platonic writer Porphyry, recorded, in the 3rd century CE, that the cave-like temple Mithraims depicted "an image of the cosmos" or "great cave" of the sky. This interpretation was supported by research by K. B. Stark in 1869, with astronomical support by Roger Beck (1984 and 1988), David Ulansey (1989) and Noel Swerdlow (1991).

It has been proposed by David Ulansey that, rather than being derived from Iranian animal sacrifice scene with Iranian precedents, the tauroctony is a symbolic representation of the constellations. The bull is thus interpreted as representing the constellation Taurus, the snake the constellation Hydra, the dog Canis Major or Minor, the crow or raven Corvus, the goblet Crater, the lion Leo, and the wheat-blood for the star Spica, the name of which means "spike of wheat". The torch-bearers may represent the constellation of Gemini which seasonally follows that of Taurus, or possibly the two equinoxes. Mithras is associated by many writers with the constellation of Orion because of the proximity to Taurus, and the consistent nature of the depiction of the figure as having wide shoulders, a garment flared at the hem, and narrowed at the waist with a belt, thus taking on the form of the constellation. It is also possible that could also be associated with Perseus, whose constellation is above that of the Taurus in the sky.

Cumont hypothesized (since then discredited) that this imagery was a Greco-Roman representation of an event in Zoroastrian cosmogony, in which Angra Mainyu (not Mithra) slays the primordial creature Gayomaretan (which in Zoroastrian tradition is represented as a bull).

Other iconography

Depictions show Mithras (or who is thought to represent Mithras) wearing a cape, that in some examples, has the starry sky as its inside lining.

A bronze image of Mithras emerging from an egg-shaped zodiac ring was found associated with a mithraeum along Hadrian's Wall (now at the University of Newcastle). An inscription from the city of Rome suggests that Mithras may have been seen as the Orphic creator-god Phanes who emerged from the world egg at the beginning of time, bringing the universe into existence. This view is reinforced by a bas-relief at the Estense Museum in Modena, Italy, which shows Phanes coming from an egg, surrounded by the twelve signs of the zodiac, in an image very similar to that at Newcastle.

Reliefs on a cup found in Mainz, appear to depict a Mithraic initiation. On the cup, the initiate is depicted as led into a location where a Pater (see Mithraic ranks) would be seated in the guise of Mithras with a drawn bow. Accompanying the initiate is a mystagogue, who explains the symbolism and theology to the initiate. The Rite is thought to re-enact what has come to be called the 'Water Miracle', in which Mithras fires a bolt into a rock, and from the rock now spouts water.

History and development

Mithras and the Bull: This fresco from the mithraeum at Marino, Italy (third century) shows the tauroctony and the celestial lining of Mithras' cape.

In antiquity, texts refer to "the mysteries of Mithras", and to its adherents, as "the mysteries of the Persians." This latter epithet is significant, not only for whether the Mithraists considered the object of their devotion a Persian divinity (i.e. Mithra), but for whether the devotees considered their religion to have been founded by Zoroaster.

It is not possible to state with certainty when "the mysteries of Mithras" developed. Clauss asserts "the mysteries" were not practiced until the 1st century CE. Mithraism reached the apogee of its popularity around the 3rd through 4th centuries, when it was particularly popular among the soldiers of the Roman Empire. Mithraism disappeared from overt practice after the Theodosian decree of 391 banned all pagan rites, and it apparently became extinct thereafter.

Although scholars are in agreement with the classical sources that state that the Romans borrowed the name of Mithras from Avestan[9] Mithra, the origins of the Roman religion itself remain unclear and there is yet no scholarly consensus concerning this issue (for a summary of the various theories, see history, below). Further compounding the problem is the non-academic understanding of what "Persian" means, which, in a classical context is not a specific reference to the Iranian province Pars, but to the Persian (i.e. Achaemenid) Empire and speakers of Iranian languages in general.

Origin theories

Cumont's hypothesis

'Mithras' was little more than a name until the massive documentation of Franz Cumont's Texts and Illustrated Monuments Relating to the Mysteries of Mithra was published in 1894-1900, with the first English translation in 1903. Cumont's hypothesis, as the author summarizes it in the first 32 pages of his book, was that the Roman religion was a development of a Zoroastrian cult of Mithra (which Cumont supposes is a development from an Indo-Iranian one of *mitra), that through state sponsorship and syncretic influences was disseminated throughout the Near- and Middle East, ultimately being absorbed by the Greeks, and through them eventually by the Romans.

Cumont's theory was a hit in its day, particularly since it was addressed to a general, non-academic readership that was at the time fascinated by the orient and its hitherto (relatively) uncharted culture. This was the age when great steps were being taken in Egyptology and Indology, preceded as it was by Max Müller's "Sacred Books of the East" series that for the first time demonstrated that civilization did not begin and end with Rome and Greece, or even with Assyria and Babylon, which until then were widely considered to be the cradle of humanity. Cumont's book was a product of its time, and influenced generations of academics such that the effect of Cumont's syncretism theories are felt even a century later.

Cumont's ideas, though in many respects valid, had however one serious problem with respect to the author's theory on the origins of Mithraism: If the Roman religion was an outgrowth of an Iranian one, there would have to be evidence of Mithraic-like practices attested in Greater Iran. However, that is not the case: No mithraea have been found there, and the Mithraic myth of the tauroctony does not conclusively match the Zoroastrian legend of the slaying of Gayomart, in which Mithra does not play any role at all. The historians of antiquity, otherwise expansive in their descriptions of Iranian religious practices, hardly mention Mithra at all (one notable exception is Herodotus i.131, which associates Mithra with other divinities of the morning star).

Further, no distinct religion of Mithra or *mitra had ever (and has not since) been established. As Boyce put it, "no satisfactory evidence has yet been adduced to show that, before Zoroaster, the concept of a supreme god existed among the Iranians, or that among them Mithra - or any other divinity - ever enjoyed a separate cult of his or her own outside either their ancient or their Zoroastrian pantheons."

It should however be noted that while it is "generally agreed that Cumont's master narrative of east-west transfer is unsustainable," a syncretic Zoroastrian (whatever that might have entailed at the time) influence is a viable supposition. This does not however imply that the religion practiced by the Romans was the same as that practiced elsewhere; syncretism was a feature of Roman religion, and the syncretic religion known as the Mysteries of Mithras is a product of Roman culture itself. "Apart from the name of the god himself, in other words, Mithraism seems to have developed largely in and is, therefore, best understood from the context of Roman culture."

Other theories

Other theories propose that Mithraism originated in Asia Minor, which though once within the sphere of Zoroastrian influence, by the second century BCE were more influenced by Hellenism than by Zoroastrianism. It was there, at Pergamum on the Aegean Sea, in the second century BCE, that Greek sculptors started to produce the highly standardized bas-relief imagery of Mithra Tauroctonos "Mithra the bull-slayer."

The Greek historiographer Plutarch (46 - 127) was convinced that the pirates of Cilicia, the coastal province in the southeast of Anatolia, were the origin of the Mithraic rituals that were being practiced in the Rome of his day: "They likewise offered strange sacrifices; those of Olympus I mean; and they celebrated certain secret mysteries, among which those of Mithras continue to this day, being originally instituted by them." (Life of Pompey 24)

Beck suggests a connection through the Hellenistic kingdoms (as Cumont had already intimated) was quite possible: "Mithras — moreover, a Mithras who was identified with the Greek Sun god, Helios, which was one of the deities of the syncretic Graeco-Iranian royal cult founded by Antiochus I, king of the small, but prosperous "buffer" state of Commagene, in the mid first century BCE."

Another possible connection between a Mithra and Mithras, though one not proposed by Cumont, is from a Manichean context. According to Sundermann, the Manicheans adopted the name Mithra to designate one of their own deities. Sundermann determined that the Zoroastrian Mithra, which in Middle Persian is Mihr, is not a variant of the Parthian and Sogdian Mytr or Mytrg; though a homonym of Mithra, those names denote Maitreya. In Parthian and Sogdian however Mihr was taken as the sun and consequently identified as the Third Messenger. This Third Messenger was the helper and redeemer of mankind, and identified with another Zoroastrian divinity Narisaf.[13] Citing Boyce,[14] Sundermann remarks, "It was among the Parthian Manicheans that Mithra as a sun god surpassed the importance of Narisaf as the common Iranian image of the Third Messenger; among the Parthians the dominance of Mithra was such that his identification with the Third Messenger led to cultic emphasis on the Mithraic traits in the Manichaean god."