Lessico

Alectoria

gemma

Gemma alettoria

Anche

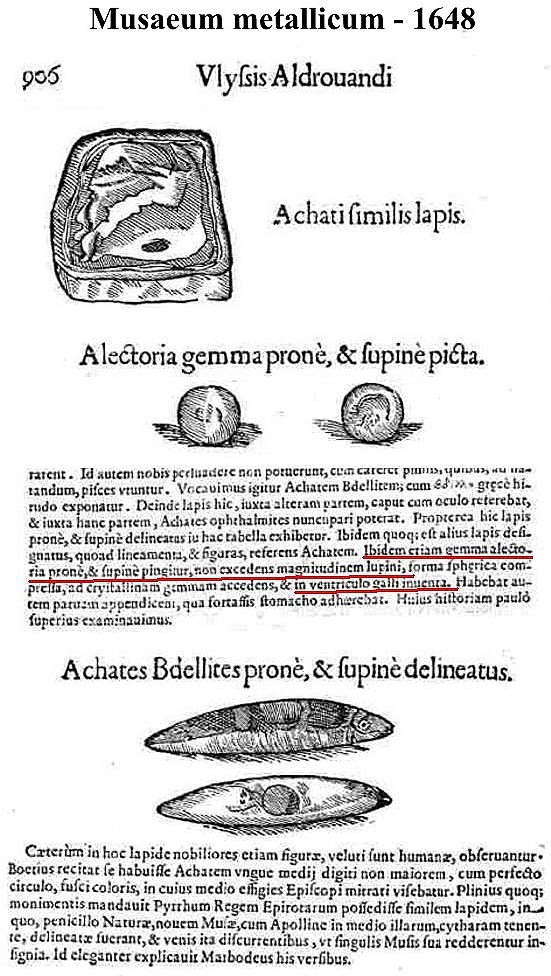

Aldrovandi cercò di sfatare l'autenticità della gemma alettoria

accostandola all'agata![]() - achates in latino - considerata una delle sue

possibili fonti.

- achates in latino - considerata una delle sue

possibili fonti.

Tuttavia a

pagina 230![]() di Ornithologiae

tomus alter (1600) non si sottrasse alla credenza - sfatata dall'odierna

biologia - cha magari le pietruzze rinvenibili nel ventriglio non siano

esogene ma che siano generate dal ventriglio stesso.

di Ornithologiae

tomus alter (1600) non si sottrasse alla credenza - sfatata dall'odierna

biologia - cha magari le pietruzze rinvenibili nel ventriglio non siano

esogene ma che siano generate dal ventriglio stesso.

Alettorio, o suoi equivalenti riferiti alla gemma alettoria, è un termine assente in alcune enciclopedie che vanno per la maggiore (De Agostini, Treccani, Encarta) nonché in dizionari moderni di italiano (Zingarelli 2008, Treccani 2003, Devoto & Oli 2005) e nell'etimologico della lingua italiana di Cortelazzo & Zolli (1999). Credo che questo buco nero della linguistica sia dovuto al fatto che nessuno crede più alla gemma alettoria.

Alettoria

è presente invece nel meno recente Tommaseo & Bellini (1865-1879) che così

esattamente riferisce: agg. e s. f. Pietra grande come una fava![]() , che

dicevan trovarsi nel ventricolo de' galli. Dal gr. Aléktør, Gallo.

–

Esatta l'etimologia di alettoria del Tommaseo & Bellini. Per curiosità posso aggiungere che il ventricolo dei galli

- e delle

galline - in dialetto alessandrino, oltre che in quello valenzano, è detto pré,

essendo preia la pietra.

, che

dicevan trovarsi nel ventricolo de' galli. Dal gr. Aléktør, Gallo.

–

Esatta l'etimologia di alettoria del Tommaseo & Bellini. Per curiosità posso aggiungere che il ventricolo dei galli

- e delle

galline - in dialetto alessandrino, oltre che in quello valenzano, è detto pré,

essendo preia la pietra.

Isidoro di

Siviglia![]() (ca.

560-636) in Etymologiae xvi,13,8 non si dilunga a descrivere e a elogiare la pietra

alettoria quando parla dei cristalli. Riferisce solamente che, grossa come una

fava, era decantata dai maghi come procacciatrice di invincibilità nelle gare

e tralascia di citare il caso classico di Milone di Crotone

(ca.

560-636) in Etymologiae xvi,13,8 non si dilunga a descrivere e a elogiare la pietra

alettoria quando parla dei cristalli. Riferisce solamente che, grossa come una

fava, era decantata dai maghi come procacciatrice di invincibilità nelle gare

e tralascia di citare il caso classico di Milone di Crotone![]() :

:

Electria, quasi alectoria: in ventriculis enim gallinaceis invenitur, crystallina specie, magnitudine fabae. Hac in certaminibus invictos fieri magi volunt, si credimus.

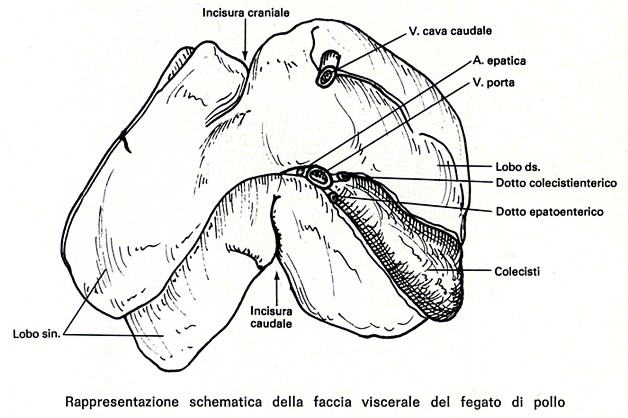

Assai

difficile affermare che la gemma alettoria può essere rinvenuta anche nella

colecisti del pollo, come afferma Georg Bauer![]() ,

le cui parole vengono citate da Gessner a pagina 382

,

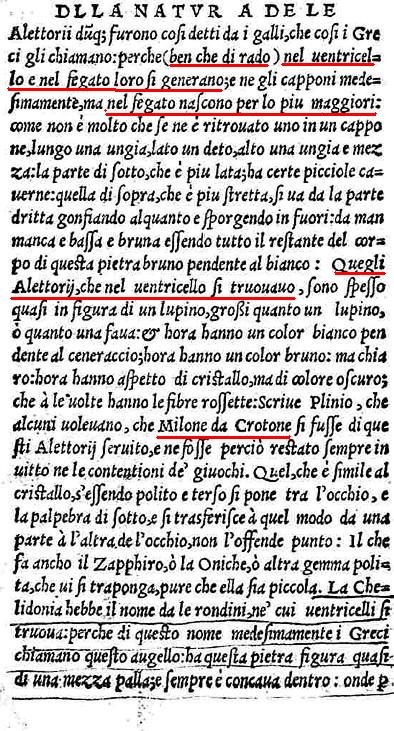

le cui parole vengono citate da Gessner a pagina 382![]() di Historia animalium III (1555): "Le alettorie, anche se

raramente, si originano nello stomaco e nel fegato dei galli e anche dei

capponi. Ma per lo più nel fegato sono di dimensioni maggiori. Infatti

recentemente nel cappone ne è stata rinvenuta una lunga un’oncia – 2,54

cm – larga un dito – circa 1,8 cm, alta un’oncia e mezza: [...]" Un

fatto è certo: se Georg Bauer ha affermato di aver rinvenuto un calcolo nella

colecisti del cappone, dobbiamo credergli, in quanto era una persona seria.

Nonostante i miei tentativi di appurare se secondo le conoscenze del XXI

secolo è descrivibile una qualche calcolosi colecistica del pollo, ho dovuto

arrendermi per mancata risposta dello scienziato interpellato, il quale l'ha

descritta nel cigno muto, Cygnus olor

di Historia animalium III (1555): "Le alettorie, anche se

raramente, si originano nello stomaco e nel fegato dei galli e anche dei

capponi. Ma per lo più nel fegato sono di dimensioni maggiori. Infatti

recentemente nel cappone ne è stata rinvenuta una lunga un’oncia – 2,54

cm – larga un dito – circa 1,8 cm, alta un’oncia e mezza: [...]" Un

fatto è certo: se Georg Bauer ha affermato di aver rinvenuto un calcolo nella

colecisti del cappone, dobbiamo credergli, in quanto era una persona seria.

Nonostante i miei tentativi di appurare se secondo le conoscenze del XXI

secolo è descrivibile una qualche calcolosi colecistica del pollo, ho dovuto

arrendermi per mancata risposta dello scienziato interpellato, il quale l'ha

descritta nel cigno muto, Cygnus olor![]() .

La relazione compare nell'apposita sezione

.

La relazione compare nell'apposita sezione![]() .

.

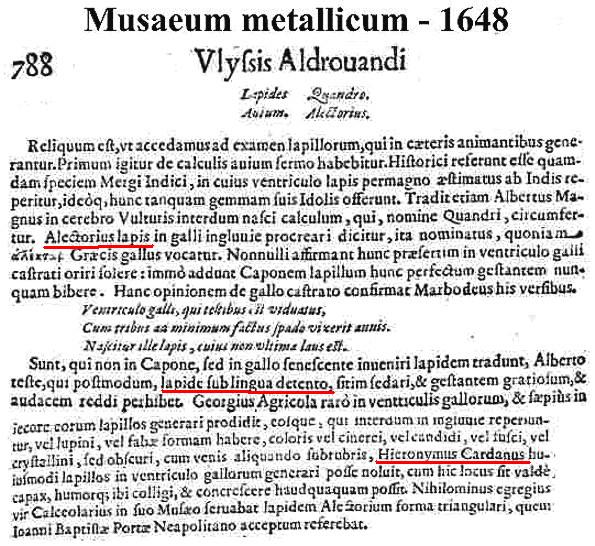

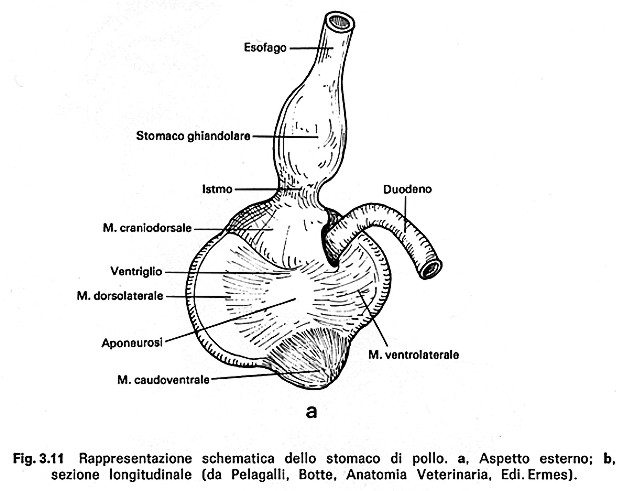

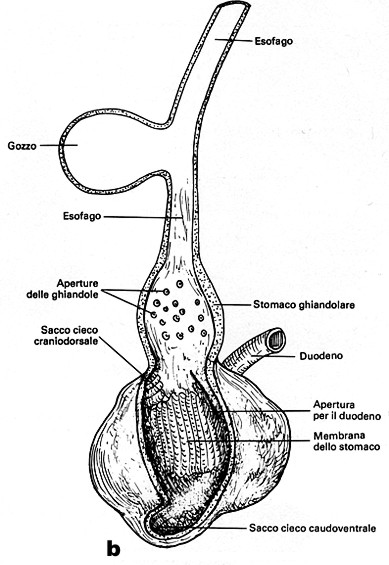

Credo valga la pena fare un succinto riassunto dell'anatomia e della fisiologia del ventriglio degli uccelli, che servirà da deterrente per coloro che ancora credono nell'esistenza e nei poteri della gemma alettoria.

Nello

stomaco muscolare del pollo, detto anche ventricolo o ventriglio, ricoperto

all'interno da coilina![]() , non è

infrequente rinvenire delle pietruzze che sono state volontariamente ingerite

e che servono a facilitare l'azione di macina del ventriglio. C'è chi

raccomanda di nutrire i pulcini con mangime al quale siano state aggiunte

scagliette di conchiglie al fine di favorire la funzione digestiva.

, non è

infrequente rinvenire delle pietruzze che sono state volontariamente ingerite

e che servono a facilitare l'azione di macina del ventriglio. C'è chi

raccomanda di nutrire i pulcini con mangime al quale siano state aggiunte

scagliette di conchiglie al fine di favorire la funzione digestiva.

E torniamo

alla gemma alettoria. A mio avviso i fattucchieri si sono messi di buona lena

a fabbricare false pietre alettorie ricorrendo, come suggerito da Gerolamo

Cardano![]() (1501-1576), a certi minerali come la

sarda

(1501-1576), a certi minerali come la

sarda![]() - oppure la corniola

- oppure la corniola![]() - e l'agata

- e l'agata![]() .

.

Era

scontato che gli antenati di Vanna Marchi non potevano non attribuire a queste

pietre dei superlativi poteri magici se volevano assicurarsi dei lauti

profitti. Ecco un esempio di come venivano decantati i poteri della pietra

alettoria da parte di un autore misconosciuto che si dedicava alle pietre. Ce

lo riferisce Conrad Gessner, Historia

Animalium III (1555) pag. 382![]() :

:

Hic

oratorem verbis facit esse disertum. | Constantem reddens cunctisque per omnia

gratum. | Hic circa veneris facit incentiva vigentes. | Commodus uxori quae vult fore grata

marito{,}<.> | Ut bona tot praestet clausus portetur in ore, Author

obscurus de lapidibus.

Questa pietra fa sì che un oratore sia incisivo con le parole. | Rendendolo

deciso e gradito sotto tutti gli aspetti. | Questa pietra rende impetuosi per

quanto riguarda gli stimoli sessuali. | È utile per una donna che vorrà

gratificare il marito. | Affinché possa offrire tanti vantaggi deve essere

portata racchiusa in bocca, autore misconosciuto circa le pietre.

Un secolo più tardi del lungimirante Cardano - forse perspicace in quanto non estraneo a pratiche magiche e astrologiche - ecco comparire l'illustre scienziato e letterato italiano Francesco Redi (Arezzo 1626 - Pisa 1698) il quale espresse i suoi dubbi sulla veridicità delle preziosissime gemme alettorie. Redi fu uno scienziato di formazione galileiana che congiunse al rigore della ricerca l'estro della fantasia, precursore dell'affermazione di un anglofono il quale, verso la fine del XX secolo, non ha avuto paura di affermare che per vincere il cancro non basta la scienza, ci vuole anche fantasia, e che gli Italiani ne hanno in abbondanza, emulando così un giorno il loro Padre Pio da Pietrelcina, al secolo Francesco Forgione.

L'altro Francesco, cioè Redi, applicando il metodo galileiano alla biologia, definì la natura del veleno viperino, sfatò la dottrina tradizionale della generazione spontanea, gettò le basi della parassitologia. Non poteva non sfatare anche i poteri e le fantasie circa la gemma alettoria in Esperienze intorno a diverse cose naturali, e particolarmente a quelle,che ci son portate dall’Indie (1686).

Ecco il testo di Cardano riferito da Conrad Gessner, Historia

Animalium III (1555) pag. 382![]() :

:

Ferunt in ventre galli alectorium, id est gallinaceum lapidem. Sed is

sarda vel achate fingitur, in quo flammea macula appareat, nam de alectoria

vero nihil comperti habeo, Cardanus.

Riferiscono che nell’addome del gallo si trova l’alettorio, cioè la

pietra del gallo. Ma quella in cui è presente una chiazza fiammeggiante viene

falsificata con la sarda - o con la corniola - oppure con l’agata, infatti a dire il

vero non ho a disposizione nulla di certo circa l’alettoria, Gerolamo

Cardano.

Ecco il testo di Redi, quando racconta il modo in cui don Antonio Morera (Canonico della Cattedrale di Goa, 400 km a SSE di Bombay) voleva fargli cessare una crisi di emicrania applicandogli una delle due pietruzze che aveva con sé e che in Malabar estraevano dal ventriglio di uccelli nerissimi simili ai corvi. Ma l'emicrania di Redi durò per le solite 24 ore, con grande frustrazione di don Antonio.

[...] quindi -

don Antonio Morera - passò a rammentarmi la virtù della Pietra

Chelidonia![]() , che secondo Dioscoride

, che secondo Dioscoride![]() , secondo Apollonio

, secondo Apollonio![]() appresso Alessandro Tralliano

appresso Alessandro Tralliano![]() , e secondo, che riferisce l’Autor del libro delle Incantagioni attribuito

a Galeno

, e secondo, che riferisce l’Autor del libro delle Incantagioni attribuito

a Galeno![]() , si trova ne’ ventrigli de’ rondinini; e la virtù parimente della

Pietra Alettoria, che pur nasce negli stomachi de’ galli, della quale Plinio

, si trova ne’ ventrigli de’ rondinini; e la virtù parimente della

Pietra Alettoria, che pur nasce negli stomachi de’ galli, della quale Plinio![]() , Alectorias vocant in ventriculis gallinaceorum inventas

crystalli specie, magnitudine fabae, quibus Milonem Crotoniensem

, Alectorias vocant in ventriculis gallinaceorum inventas

crystalli specie, magnitudine fabae, quibus Milonem Crotoniensem![]() usum in

certaminibus invictum fuisse videri volunt. E Solino

usum in

certaminibus invictum fuisse videri volunt. E Solino![]() : Victor Milo omnium certaminum, quae obivit, Alectoria usus traditur; qui

lapis specie crystallina, fabae modo, in gallinaceorum ventriculis invenitur,

aptus, ut dicunt, proeliantibus. Ed un Poeta copiator di Solino:

: Victor Milo omnium certaminum, quae obivit, Alectoria usus traditur; qui

lapis specie crystallina, fabae modo, in gallinaceorum ventriculis invenitur,

aptus, ut dicunt, proeliantibus. Ed un Poeta copiator di Solino:

Est et

Alectorius gallorum in ventre lapillus

Ut faba, crystalli specie, pugnantibus aptus.

Io me ne risi dentro il mio

cuore; e con ogni piacevolezza cercai di persuadere a lui, e di fargli toccar

con mano, che quelle pietre non nascevano in que’ ventrigli, ma che elle vi

si trovavano, perchè erano state in prima inghiottite da essi uccelli, i

quali non eran soli ad aver questa naturalezza d’inghiottir le pietre, ma

che l’ingojavano ancora tutte quante l’altre spezie di uccelli domestichi,

e salvatichi; Ed effettivamente pochi giorni appresso gliele feci vedere in

molti, e molti ventrigli di differenti generazioni di volatili, e spezialmente

nelle Gru, le quali ve ne aveano una grandissima quantità.

Esperienze intorno a diverse cose naturali,

e

particolarmente a quelle,che ci son portate dall’Indie - 1686

www.liberliber.it

La

gemma alettoria

della colecisti del pollo

È stato inutile inviare per ben due volte, la prima lunedì 9 giugno

2008, la preghiera di risolvere il mio quesito circa la possibilità di

formazione di calcoli biliari nel pollo. La preghiera fu inviata via e-mail

all'Associate Professor Janet Patterson-Kane BVSc, PhD,

Diplomate ACVP, School of Veterinary Science, University of Queensland,Brisbane,

Austalia. Nessun riscontro, per cui il busillis relativo al fatto se i polli

possano presentare una calcolosi biliare rimane insoluto, e dobbiamo affidarci

a Georg Bauer![]() , come possiamo vedere nel suo testo

, come possiamo vedere nel suo testo![]() .

.

Forse è difficile rinvenire una calcolosi della colecisti nel pollo in quanto nel 99,999% dei casi va incontro a morte in tenera età per puri motivi gastronomici, mentre quel pollo che raggiunge un'età rapportabile a quella di Matusalemme (969 anni), viene debitamente sepolto con tutti gli onori riservati a un animale domestico d'affezione, quindi, senza essere sottoposto ad autopsia che sarebbe in grado di risolvere il quesito circa la calcolosi biliare nel genere Gallus.

Dear Professor Janet Patterson-Kane,

Sorry in disturbing you about gall bladder lithiasis in birds, but I have found in the web the quotation of your "Cholelithiasis and chronic cholangiohepatitis in a mute swan (Cygnus olor) (2006)"and so I think you can help me.

The problem arose because of the translation of the section regarding chickens in Historia animalium III (1555) of Conrad Gessner. At page 382 he quotes different authors about the alectoria stone, alectoria meaning "of the rooster", alektor being in Greek the rooster, a stone found in the gizzard of the rooster. He also quotes Georg Bauer (Georgius Agricola 1494–1555) a German scholar and scientist known as "the father of mineralogy".

Bauer in his De rerum fossilium (1550) affirms that these alectoriae stones usually in the liver are of greater dimensions.

I never have read about stones in liver (gall bladder) of birds, except in the title of your research and in Bauer. But never, in my experience, I have heard about special stones found in the gizzard and less than ever in gall bladder of chickens.

Perhaps there is an explanation: it is impossible to find stones in gall bladder of chickens because they die very young thanks to the table of humans. If in chickens it happens like the cholelithiasis of humans, we need that chickens are living for a lot of years.

In fact, as you can read also underneath, these stone are better found (in gizzard, or perhaps in liver?) after 4 or 9 years from castration of the rooster: "Albertus – Albertus Magnus - writes that the stone is glimmering, similar to a dark crystal. And it is extracted from the stomach of the rooster after the fourth year from castration. Some say that it is extracted after the ninth year. Better is that removed from a decrepit rooster. In this kind of rooster the greatest one is big as a broad bean."

MY QUERY

Do you think that TRULY, as Bauer affirms, the cholelithiasis can affect the chickens?

If you agree, is the cholelithiasis affecting ONLY AGED chickens like it happens in humans?

Many

thanks for your attention and patience.

Sincerely yours,

Dr Elio Corti

De la generatione de le cose fossili - 1550

The crop

Not present in all birds, the crop serves more or less as a "doggy bag" when the bird eats. Notice the crop in the picture above. Let's say you're a Song Sparrow and you discover a weed just loaded with delicious-looking seeds, but the weed grows in the open. If you flit into the open area to eat the weed's seeds, you're making yourself vulnerable to predators who want to eat you. What to do?

What you do is to flit into the open and gobble up those seeds far faster than any stomach could possibly handle them, then fly to safety. You can do this because of your crop. For, as you cram in those seeds, a few at first go straight to the gut but, when that fills, further seeds begin detouring to the bag-like crop. Once the crop is full of seed, you fly to your favorite perch, and now there's not much to do but let your stomach digest. As those first seeds in the stomach begin working their way through the rest of the body, seeds stored in the crop automatically refill the stomach. If someday you pick up a bird, perhaps one that has flown into a window and you want to save it from the cat, if that bird has recently eaten, you well may be able to feel the crop in the chest area, feeling like a bag filled with grit right below the feathers.

Actually, specialists in the field of bird guts would want to insist that

some birds have real crops, other birds have pseudocrops, and that there are

other croplike variations, but we don't want to get too confused so we'll just

leave it at that.

The two-chambered stomach:

The proventriculus

The stomach is an amazing affair consisting of two chambers. The proventriculus is the first chamber. It secretes an acid for breaking down food, and is best developed in birds that swallow entire fish and other animals containing bones which must be digested. If you know a little chemistry, you'll know how amazing it is that bird stomach-acid can have a pH as low as 0.2. In most of North America there's a kind of bird known as a shrike (Lanius species), which eats small animals, especially rodents and songbirds. A shrike's well developed first stomach-chamber can digest an entire mouse in only three hours!

The gizzard

The bird stomach's second chamber is known as the gizzard. If you've ever eaten a chicken gizzard you know how tough and rubbery it is. To accomplish what the gizzard does, it absolutely must be tough, for the gizzard's main function is to grind and digest tough food. Though the gizzard consists of very powerful muscles, it alone can't pulverize everything the typical bird eats; you know how hard uncooked rice and corn kernels are, and these aren't even considered hard types of grain.

Something other than muscle power is needed. This "something else" is acquired when grain-eating birds pick up grit and small rocks as they peck seeds from the ground.

This mineral matter accumulates in the gizzard, and ultimately the gizzard grinds the particles against the seeds, smashing them. Turkey gizzards can actually pulverize English walnuts and steel needles! Bird species that eat softer food possess less well developed gizzards. In some species, the gizzard remains small and insignificant during the summer when the diet consists of soft food such as flesh, insects, or fruit, but it grows more powerful during the winter when seeds are the main food. Since birds eat such a wide variety of foods, you can imagine that variations on the stomach theme are many. One of the most elegant is found among grebes, which are very common water-birds you're bound to see if you visit local lakes or the seashore. Grebes swallow their own feathers, which accumulate in the region between the gizzard and the intestine following it. This feather-clogged zone then serves as a filter for sharp fish bones that somehow make it past the stomach.

Owl

pellets

products of a special gizzard

Several hours after an owl eats, the fur, bones, teeth & feathers of its prey still in the gizzard are compressed into a pellet the same shape as the gizzard. Once formed, the pellet moves up from the gizzard to the proventriculus, where it remains for up to 10 hours before being regurgitated. Owls can't eat while a fully formed pellet is present, blocking the digestive track. When an Owl is ready to produce a pellet it usually closes its eyes, gets a funny luck in its face, doesn't want to fly and, when the pellet is ready to come out, the beak is opened and the pellet simply drops out. Other birds of prey, such as hawks, also produce pellets but the owl's digestive juices are less acidic than those of other birds of prey, so there is more material present to form a pellet.

www.backyardnature.net/birds.htm

Duck gizzard

Etymology

The word gizzard comes from the Middle English giserdd, which derives from a similar word in Old French, giser, and earlier from the Vulgar Latin *gicerium, which follows from the Latin word gigeria, meaning cooked entrails of poultry, a delicacy in ancient Rome. The Latin word gigeria probably is derived from the Persian word for liver, which is jiger.

Structure

Birds swallow food and store it in their crop if necessary. Then the food passes into their glandular stomach, also called the proventriculus, which is also sometimes referred to as the true stomach. This is the secretory part of the stomach. Then the food passes into the ventriculus (also known as the muscular stomach or gizzard). The gizzard can grind the food with stones that have been swallowed and pass it back to the true stomach and vice versa. Bird gizzards are lined with a tough layer made of the protein keratin, to protect the muscles in the gizzard.

Gizzard stones

Some animals that lack teeth will swallow stones or grit to aid in digestion. All birds have gizzards, but not all will swallow stones or grit. The birds that do, employ the following method of 'mastication':

"A bird swallows small bits of gravel that act as 'teeth' in the gizzard, breaking down hard food such as seeds and thus helping digestion." (Solomon et. al, 2002).

These stones are called gizzard stones or gastroliths and are usually smooth and round from the polishing action in the animal's stomach. When too smooth to do their required work, they may be passed or regurgitated.

Animals with gizzards

Emus, turkeys and chickens, like all birds, have gizzards. Mullets (Mugilidae) found in estuarine waters worldwide, and the gizzard shad, or mud shad, found in freshwater lakes and streams from New York to Mexico, have gizzards. The Gillaroo (Salmo stomachius), has a gizzard. It is a species of trout found in Lough Melvin in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. It is a distinct species, characterized by a rich coloration. Its gizzard is used to aid the digestion of water snails, the main item of its diet. Crocodiles also have gizzards.

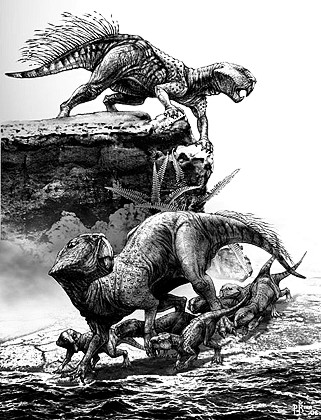

Dinosaurs with gizzards

Psittacosaurus

Dinosaurs believed to have had gizzards based on the discovery of gizzard stones recovered near fossils:

Claosaurus

Psittacosaurus

Massospondylus

Sellosaurus

Omeisaurus

Apatosaurus

Barosaurus

Dicraeosaurus

Seismosaurus

Eating gizzards

Fried gizzards and livers

The gizzards of poultry are a popular food throughout the world. Grilled chicken gizzards are sold as street food in South Korea, China, Taiwan, Japan, Philippines, Haiti, and throughout Southeast Asia. Stewed gizzards are eaten as a snack in Portugal, while pickled turkey gizzards are a traditional food in some parts of the Midwestern United States. In Hungary it is made with paprika. In the Southern United States, the gizzard is typically served fried, sometimes eaten with hot or honey mustard, or added to crawfish boil along with crawfish sauce. In Chicago, gizzard is battered, deep fried and served with fries and sauce. Gizzard and mashed potato is a popular food in many European countries. In France, especially the Dordogne region, gizzards are eaten in the traditional Perigordian Salad, along with walnuts, croutons and lettuce.

In Yiddish, gizzards are referred to as "pipik'lach", literally meaning navels. The gizzards of kosher species of birds have a green or yellowish membrane lining the inside, which must be peeled off before cooking, as it lends a very bitter taste to the food. In traditional Eastern European Jewish cuisine, the gizzards, necks, and feet of chickens were often cooked together, although not the liver, which per Kosher law must be broiled.

In Cameroon and Nigeria, the gizzard of a cooked chicken is traditionally set aside for the oldest or most respected male at the table. Giblets consist of the heart, liver and gizzard of a bird, and are often eaten themselves or used as the basis for a soup or stock. Gizzards can also refer to the general guts, innards or entrails of other animals, as in the phrase 'hand over the treasure or I'll slit yer gizzards me hearty' that may be uttered by a storybook pirate.

I gastroliti - pietre del ventre - sono rocce geologiche che sono o sono state inglobate nel tratto digerente di un animale. Tra i vertebrati viventi, i gastroliti sono comuni tra gli uccelli erbivori, i coccodrilli e le foche. Alcuni animali estinti, come i dinosauri teropodi, simili a uccelli, sembrerebbero aver usato gastroliti per macinare piante dure. I gastroliti si trovano solo raramente nei dinosauri sauropodi e una triturazione del cibo con pietre non è plausibile. Animali acquatici, come i plesiosauri, potrebbero aver utilizzato i gastroliti per aiutare a bilanciarsi e a regolare il loro nuoto, come fanno anche i coccodrilli. Maggiori ricerche sono necessarie per capire la funzione delle pietre negli animali acquatici. Mentre alcuni gastroliti fossili sono arrotondati e levigati, molte pietre ritrovate in uccelli attuali non sono levigate affatto. I gastroliti ritrovati in associazione con resti di dinosauri possono pesare svariati chilogrammi. Pietre inghiottite dagli struzzi possono raggiungere la lunghezza di oltre dieci centimetri.

Prove fossili

I geologi di solito richiedono alcune prove prima di accettare il fatto che una roccia sia stata usata da un dinosauro per aiutare la sua digestione. Per prima cosa, la pietra deve essere dissimile dalle altre rocce nella sua vicinanza geologica. In secondo luogo, la pietra dovrebbe essere arrotondata e levigata, dal momento che dentro a uno stomaco di un dinosauro ogni effettivo gastrolite avrebbe agito contro le altre pietre e il materiale fibroso come un levigatore naturale. In ultimo, la pietra deve essere stata ritrovata in associazione con le ossa del dinosauro che l'ha ingerita. È questo ultimo criterio che causa incertezze nella classificazione, dal momento che pietre arrotondate trovate senza contesto possono essere catalogate (possibilmente i modo erroneo, in alcuni casi) come pietre levigate da acqua o vento.

Distinzione dalle pietre levigate

I gastroliti possono essere distinti da rocce arrotondate da correnti in base ad alcuni criteri: i gastroliti sono altamente lucidati sulle superfici più alte, mentre nelle depressioni o nelle piccole crepe non lo sono per nulla, rendendosi spesso simili a denti danneggiati. Le rocce danneggiate da correnti, in particolare in ambienti di alto impatto, mostrano minore levigatura sulle superfici alte, spesso con molti piccoli buchi o rotture su queste superfici. Infine, i gastroliti altamente levigati spesso mostrano lunghi graffi microscopici, presumibilmente causati dal contatto con un angolo aguzzo di una pietra ingerita da poco. Dal momento che la maggior parte dei gastroliti si sono sparsi quando l'animale è morto, e molti di essi sono entrati a far parte di un ambiente di corrente o di spiaggia, alcuni gastroliti mostrano una mescolanza di queste caratteristiche. Altri sono indubbiamente stati inghiottiti da altri dinosauri, e gastroliti altamente levigati potrebbero essere stati ripetutamente inghiottiti.

Esempi di gastroliti fossili

Uno scheletro di Psittacosaurus, proveniente dalla formazione Ondai Sair (Cretaceo inferiore della Mongolia) mostra una collezione di circa quaranta gastroliti all'interno della cassa toracica, tra le spalle e la pelvi. La Cedar Mountain Formation del Cretaceo inferiore dello Utah centrale è piena di selci bianche e rosse altamente levigate che potrebbero essere in parte rappresentare gastroliti. È interessante notare che le selci potrebbero esse stesse contenere fossili di antichi animali, come coralli. Queste pietre non sembrano essere associate con depositi di correnti e sono raramente più grandi di un pugno, il che è in accordo con l'idea che potrebbero essere gastroliti. I gastroliti sono spesso chiamati "pietre della Morrison" perché sono spesso trovati nella Morrison Formation (chiamata così dalla città di Morrison, Colorado), una formazione del tardo Giurassico di circa 150 milioni di anni fa. Alcuni gastroliti sono formati da legno pietrificato.

Importanza dei gastroliti

I paleontologi stanno ricercando nuovi metodi per identificare i gastroliti trovati non in associazione con resti di animali, a causa delle importanti informazioni che possono fornire. Se la validità di gastroliti simili può essere verificata, potrebbe essere possibile tracciare un percorso delle rocce gastroliti fino alle loro origini. Questo potrebbe recare importanti informazioni riguardo a possibili migrazioni di dinosauri. A causa del fatto che il numero d gastroliti è ampio, queste pietre potrebbero addurre nuovi punti di vista sulla vita e il comportamento dei dinosauri.

Gastroliths ('stomach stones' or 'gizzard stones') are rocks, which are or have been held inside the digestive tract of an animal. Among living vertebrates, gastroliths are common among herbivorous birds, crocodiles, alligators, seals and sea lions. Domestic fowl, for instance, require access to 'grit', for the purpose of food-grinding. Gastroliths are retained in the very muscular gizzard and serve the masticatory function of teeth, in an animal without suitable grinding teeth. The grain size of the gastrolith depends upon the size of the animal and its special needs. Particles as small as sand and stones the size of cobbles or greater have been found.

Some extinct animals, such as sauropod dinosaurs, appear to have used stones to grind tough plant matter. Gastroliths have only rarely been found in association with fossils of theropod dinosaurs and a trituration of their food with the stones is not plausible. Aquatic animals, such as plesiosaurs, may have used them as ballast, to help balance themselves or to decrease their buoyancy, as crocodiles do. More research is needed to understand the function of the stones in aquatic animals. While some fossil gastroliths are rounded and polished, many stones in living birds are not polished at all. Gastroliths associated with dinosaur fossils can be several kilograms in weight. Stones swallowed by ostriches can also reach a length of more than 10 cm.

Geologists usually require several pieces of evidence before they will accept that a rock was used by a dinosaur to aid its digestion. First, the stone must be unlike the rock found in its geological vicinity. Secondly, it should be rounded and polished, because inside a dinosaur's gizzard any genuine gastrolith would have been acted upon by other stones and fibrous materials in a process similar to the action of a rock tumbler. Lastly, the stone must be found with the bones of the dinosaur which ingested it. It is this last criterion that causes trouble in identification, as smooth stones found without context can (possibly erroneously in some cases) be dismissed as having been polished by water or wind. Whittle (1988,9) pioneered scanning electron microscope analysis of wear patterns on gastroliths. Wings (2003) found that ostrich gastroliths would be deposited outside the skeleton if the carcass was deposited in an aquatic environment for as little as a few days following death. He concludes that this is likely to hold true for all birds (with the possible exception of moa) due to their air-filled bones which would cause a carcass deposited in water to float for the time it needs to rot sufficiently to allow gastroliths to escape.

Gastroliths can be distinguished from stream- or beach-rounded rocks by several criteria: gastroliths are highly polished on the higher surfaces, with little or no polish in depressions or crevices, often strongly resembling the surface of worn animal teeth. Stream- or beach-worn rocks, particularly in a high-impact environment, show less polishing on higher surfaces, often with many small pits or cracks on these higher surfaces. Finally, highly polished gastroliths often show long microscopic hairline scratches, presumably caused by contact with a sharp corner of a freshly swallowed stone. Since most gastroliths were scattered when the animal died and many entered a stream or beach environment, some gastroliths show a mixture of these wear features. Others were undoubtedly swallowed by other dinosaurs and highly polished gastroliths may have been swallowed repeatedly.

The American Museum of Natural History Photograph # 311488 demonstrates an articulated skeleton of a Protiguanadon mongoliense, from the Ondai Sair Formation, Lower Cretaceous Period of Mongolia, showing a collection of about 40 gastroliths inside the rib cage, about midway between shoulder and pelvis.

The Early Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation of Central Utah is full of highly polished red and black cherts, which may partly represent gastroliths. Interestingly, the cherts may themselves contain fossils of ancient animals, such as corals. These stones do not appear to be associated with stream deposits and are rarely more than fist-sized, which is consistent with the idea that they are gastroliths. Gastroliths have sometimes been called 'Morrison stones' because they are often found in the Morrison Formation (named after the town of Morrison, west of Denver, Colorado), a late Jurassic formation roughly 150 million years old. Some gastroliths are made of petrified wood.

Paleontologists are researching new methods of identifying gastroliths that have been found disassociated from animal remains, because of the important information they can provide. If the validity of such gastroliths can be verified, it may be possible to trace gastrolithic rocks back to their original sources. This may provide important information on how dinosaurs migrated. Because the number of suspected gastroliths is large, they could provide significant new insights into the lives and behavior of dinosaurs.

Alectormancy (also known as Alectromancy, Alectoromancy or Alectryomancy, derivation comes from the Greek words alectryon and manteia, which mean rooster and divination respectively) is a form of divination in which a bird is subjected to random picking of corn grains from a circle of letters and any divination that involves roosters. Alectormancy is also sacrificing a sacred rooster.

Roosters were commonly used for predictions in different parts of the world, and over the ages different methods were used. The most common and popular form of this divination based on the observation of a rooster eating corn scattered on letters. This practice was used when the sun or the moon was in Aries or Leo. A circle of letters (originally twenty-four in number, since j, v are the same as i, u) was traced on the ground and laid out with some sort of grain placed on each letter. Next a rooster, usually a white one, was let pick at the grains, thus selecting letters to create a divinatory message or sign. The chosen letters could be either read in order of selection, or rearranged to make an anagram. Sometimes readers got 2 or 3 letters and interpreted them. Additional grains replaced those taken by the rooster.

In Africa, a black hen or a gamecock is used. An African diviner sprinkles grain on the ground and when the bird has finished eating, the seer interprets the designs or patterns left on the ground. Another method of alectormancy, supposedly used less often, was based on reciting letters of the alphabet noting those at which a cock crows. Letters were recorded in sequence and then these letters were interpreted as the answer to the question chosen by seers.

A rare, obsolete meaning of alectormancy is "a divination by a cock-stone". A cock-stone or alectoria was "a christall coloured stone (as big as a beane) found in the gyzerne, or maw of some cockes" (Cotgrave). These stones, purportedly found in a roosters gizzard, were known to the Romans (in Latin they were called alectoria gemma, literally "cock's gem") and were imputed with magical powers. Apparently they were used for some sort of lithomantic divination, though the details of this use are not to be found. Alectormancy was also used in Ancient Rome to identify thieves.

Superstitions

about the Cock Stone

or Alectorius Stones

Stones from the cock are also called alectorius stones and they were believed to aid wrestlers and married couples as well as serving as medical antidotes for poisons. The alectorius or "cock-stone" is one of the most famous of those real or supposed animal concretions that were known in ancient times. From the age of Pliny -- and unquestionably long before his time -- there was a popular belief that this stone was only to be found in the gizzard of a cock which had been caponed when three years old, and had lived seven years longer. This was believed to allow the substance to acquire its boasted virtue, for the longer it remained in the body of the capon, the greater its power.

Such a cock-stone never exceeded the size of a bean. From its association with the pugnacious fowl, the alectorius became a favorite stone with wrestlers, and the great and invincible Milo of Croton is said to have owned many of his victories to the possession of one, for if held in the mouth, it quenched the thirst and thus refreshed the combatant.

Many other virtues of this stone are recorded: it rendered wives agreeable to their husbands, dissolved enchantments, brought new honors and powers in addition to those already enjoyed, and helped kings to acquire new dominions. How persistent was the faith in the virtue of the alectorius is shown by the fact that the great Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (known in Italy as Ticone, Knudstruh 1546 - Prague 1601) greatly valued a stone of this kind, not larger than a bean, and believed that it brought him luck in gambling and in love. The Dominican Thomas de Cantimpré (1201-1270/72) says that the name signifies an allurer or enticer, because the stone excites the love of husbands for their wives. In order to secure the due effect it should be held in the mouth, possibly because this would render the wife less eloquent.

A specimen of the alectorius is listed in the inventories of Jean Duc de Berry (1401-1416). It is called there a capon-stone and is described as having red and white spots. Several other objects to which talismanic virtues were ascribed are also noted, such, for instance, as the "molar of a giant," set in leather; probably the tooth of a hippopotamus, or the fossil tooth of some antediluvian creature. There is also what is termed a "tester," composed of several "serpent's teeth" (glossopetrae?), horns of the "unicorn" (narwhal's teeth) and stones regarded as antidotes to poison. These were all suspended by golden chains, and were valued at seventy-five livres tournois.

As a companion piece to the cock-stone, the hen furnished a concretion possessing special virtues. This came from the fowl's gizzard and was of a sky-blue color; its Arabic name was hajar al-hattaf. If it were worn by an epileptic, the attacks of his malady would cease; it favored procreation and also nullified the effects of the Evil Eye, and it kept children from having bad dreams if placed beneath their heads when they were sleeping. Thus the effects it was fancied to produce differed from those ascribed to the alectorius.

In medieval times bunches of dried "serpent's tongues" were sometimes hung around salt-cellars or attached to spits; but frequently, for royal or princely use, such tongues, or the jawbones of snakes, were set with valuable precious stones and constituted a peculiar jewel termed in old French a languier, or epreuve (tester); for these utensils, often very rich and tasteful specimens of the goldsmith's art, were believed to show in some way the presence of the much-dreaded poison in any viands with which they were brought in contact.

www.jjkent.com