Lessico

Orapollo Niloo

In greco Ὡραπόλλων. Scrittore egiziano di Nilopoli (a ovest del Nilo, in prossimità del lago Meris, 6 km a sudovest di Menfi, a sua volta 24 km a sud del Cairo), autore di un’opera in due libri in lingua copta sui geroglifici, non anteriore al sec. IV dC, tradotta in cattivo greco da un certo Filippo. L’opera - Hieroglyphiká - è generalmente attribuita a Orapollo che diresse una delle ultime scuole pagane, quella di Menouthis, presso Alessandria, ai tempi di Zenone, imperatore romano d'Oriente dal 474 al 491. È incerta l'identificazione con il grammatico omonimo vissuto sotto il regno del l'imperatore romano d'Oriente Teodosio II, durato dal 408 al 450. L'opera non rivela una vera conoscenza dell’antica scrittura e basa le spiegazioni sulle magie e superstizioni in cui l’antica religione egizia si era mutata.

Il testo

greco dei Hieroglyphiká fu scoperto nel 1419 da Cristoforo Buondelmonti![]() nell’isola greca di Andros nel Mar Egeo, la più

settentrionale delle Cicladi, nella cui provincia è inclusa. L’arrivo a

Firenze, nel 1422, del manoscritto dei Hieroglyphiká, acquistato da

Buondelmonti per conto di Cosimo de' Medici, suscitò scalpore, poiché

finalmente si aveva un’opera che, si riteneva, sarebbe stata in grado di

spiegare il senso occulto dei misteriosi geroglifici egizi. Il testo

presentava numerose lacune, ma, nonostante questo, conobbe un’ampia

diffusione e fu oggetto di appassionate discussioni, tanto da essere, per

tutto il Rinascimento, all’origine delle idee che si avevano sui

geroglifici.

nell’isola greca di Andros nel Mar Egeo, la più

settentrionale delle Cicladi, nella cui provincia è inclusa. L’arrivo a

Firenze, nel 1422, del manoscritto dei Hieroglyphiká, acquistato da

Buondelmonti per conto di Cosimo de' Medici, suscitò scalpore, poiché

finalmente si aveva un’opera che, si riteneva, sarebbe stata in grado di

spiegare il senso occulto dei misteriosi geroglifici egizi. Il testo

presentava numerose lacune, ma, nonostante questo, conobbe un’ampia

diffusione e fu oggetto di appassionate discussioni, tanto da essere, per

tutto il Rinascimento, all’origine delle idee che si avevano sui

geroglifici.

Orapollo

Scrittore egiziano nato a Nilopoli (a ovest del Nilo, in prossimità del lago Meris, 6 km a sudovest di Menfi, a sua volta 24 km a sud del Cairo) che diresse una delle ultime scuole pagane, quella di Menouthis, presso Alessandria, ai tempi di Zenone, imperatore romano d'Oriente dal 474 al 491. È incerta l'identificazione con il grammatico omonimo vissuto sotto il regno dell'imperatore romano d'Oriente Teodosio II, durato dal 408 al 450.

È autore di un'opera intorno ai geroglifici, composta forse in lingua copta, di cui possediamo una versione greca, opera di un ignoto Filippo, intitolata appunto Hieroglyphiká e divisa in due libri, rispettivamente di 70 e 119 capitoli. Contiene l'interpretazione dei segni e la spiegazione dei motivi per cui a un certo segno corrisponde una data idea, sulla base di interpretazioni simboliche spesso originali e fantasiose.

Il testo

fu portato a Firenze da Cristoforo Buondelmonti![]() nel 1422 ed esercitò il

suo influsso sulla tradizione ermetica e neoplatonica fiorentina, alimentando

la credenza in un sapere più antico di quello classico, depositato in un

linguaggio misterioso accessibile solo agli iniziati. La prima edizione del

trattato è del 1505 (Venezia, Aldo Manuzio

nel 1422 ed esercitò il

suo influsso sulla tradizione ermetica e neoplatonica fiorentina, alimentando

la credenza in un sapere più antico di quello classico, depositato in un

linguaggio misterioso accessibile solo agli iniziati. La prima edizione del

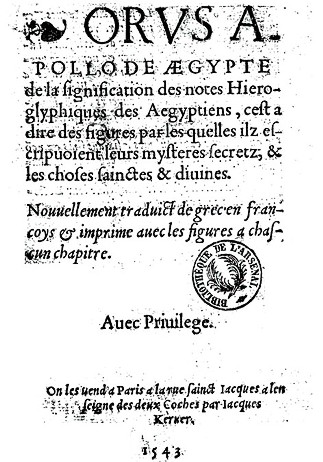

trattato è del 1505 (Venezia, Aldo Manuzio![]() ), ma nel Cinquecento apparve anche

in traduzioni latine (a cura di Filippo Fasanini, Bologna, G. de Benedictis,

1517) e in lingue moderne: italiano a cura di Pietro Vasolli (Venezia,

Gabriele Giolito, 1547); francese a cura di J. Martin (Parigi, 1543); tedesca

a cura di J. Herold (Basilea, 1554).

), ma nel Cinquecento apparve anche

in traduzioni latine (a cura di Filippo Fasanini, Bologna, G. de Benedictis,

1517) e in lingue moderne: italiano a cura di Pietro Vasolli (Venezia,

Gabriele Giolito, 1547); francese a cura di J. Martin (Parigi, 1543); tedesca

a cura di J. Herold (Basilea, 1554).

www.italica.rai.it

We know

of Horapollo through Suda![]() , who

mentions him in ω 159 (Ὡραπόλλων) as the leader of one of the

last pagan schools of Menouthis, near Alexandria, during the reign of Emperor

Zeno (474-491), from where he was forced to flee when he became involved in a

revolt against the Christians. His school was shut down, his temple of Isis

and Osiris

, who

mentions him in ω 159 (Ὡραπόλλων) as the leader of one of the

last pagan schools of Menouthis, near Alexandria, during the reign of Emperor

Zeno (474-491), from where he was forced to flee when he became involved in a

revolt against the Christians. His school was shut down, his temple of Isis

and Osiris![]() destroyed, and he, after being

subjected to torture, finally converted to Christianity.

destroyed, and he, after being

subjected to torture, finally converted to Christianity.

Nevertheless, in the same

entry, Suda alludes to another Horapollo – probably the former’s uncle –

a grammarian from Phanebytis during the reign of Theodosius II (408-450) who

taught in Alexandria and Constantinople. Beginning in the sixteenth century,

the Hieroglyphiká

were usually attributed to him. There were other

spurious traditions that ascribed the work to a king of Egypt, Horus, son of

Osiris, or even to the god Horus himself![]() , as can be read on the cover of the

translation of the manuscript by Nostradamus (Rollet’s ed., 1968): "Horapollo,

Son of Osiris, King of Egypt".

, as can be read on the cover of the

translation of the manuscript by Nostradamus (Rollet’s ed., 1968): "Horapollo,

Son of Osiris, King of Egypt".

Other fragments from Suda help

us to reconstruct Horapollo’s intellectual world: select philosophical

circles, of an élite educational background, who carefully gathered together

the last traces of the Egyptian past, and admired the relics of ancient cults,

reinterpreting that legacy in the light of contemporary Neoplatonism. Prior to

Horapollo, Egyptian culture, as well as knowledge about the hieroglyphics, had

been propagated in Greek by Manetho![]() , Bolus of Mende, Apion and Caeremon. All

of their works, which have only survived in fragmentary form, were written in

the same style as the Hieroglyphiká

by Horapollo, the only complete

ancient treatise on Egyptian hieroglyphics.

, Bolus of Mende, Apion and Caeremon. All

of their works, which have only survived in fragmentary form, were written in

the same style as the Hieroglyphiká

by Horapollo, the only complete

ancient treatise on Egyptian hieroglyphics.

The Hieroglyphica

The two books of the Hieroglyphiká contain in total 189 interpretations of hieroglyphs: Book I describes 70, and Book II 119. In the Renaissance they were generally considered to be authentic Egyptian characters, and although this authenticity was seriously placed in doubt during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, modern-day Egyptology recognizes that Book I in its entirety and approximately one third of Book II are based on real signs from hieroglyphic writing.

Nevertheless, their interpretation does

not follow their functional meaning in the Egyptian system of writing, but

rather a presumably loftier moral, theological or natural decoding of reality,

in exactly the same way that the Physiologus![]() was interpreted at around the same time. This genre of the symbolic

rereading of the hieroglyphs – "enigmatic hieroglyphs" as Rigoni

and Zanco (1996) call them – was very popular in the late Hellenistic period.

It should not surprise us, then, that so many Renaissance Humanists – for

whom this was all quite familiar through Lucan

was interpreted at around the same time. This genre of the symbolic

rereading of the hieroglyphs – "enigmatic hieroglyphs" as Rigoni

and Zanco (1996) call them – was very popular in the late Hellenistic period.

It should not surprise us, then, that so many Renaissance Humanists – for

whom this was all quite familiar through Lucan![]() , Apuleius

, Apuleius![]() , Plutarch

, Plutarch![]() , Clement of Alexandria

, Clement of Alexandria![]() and, especially, Ennead V by Plotinus – should see in the Hieroglyphiká

a genuine connection with the highest sphere of wisdom.

and, especially, Ennead V by Plotinus – should see in the Hieroglyphiká

a genuine connection with the highest sphere of wisdom.

The

part of the Hieroglyphiká

that does not deal with hieroglyphics –

chaps. 31-117 of Book II – may well have served to encourage even more this

type of reading, by including animal allegorization derived principally from

Aristotle![]() ,

Aelian

,

Aelian![]() , Pliny

, Pliny![]() and

Artemidorus

and

Artemidorus![]() . These

renovated symbols were added to the original material by the Greek translator,

who, in the introduction to Book II, affirms explicitly that they are «interpretations

of signs gathered from diverse sources».

. These

renovated symbols were added to the original material by the Greek translator,

who, in the introduction to Book II, affirms explicitly that they are «interpretations

of signs gathered from diverse sources».

The manuscript of the Hieroglyphiká

made its way to Florence, from the

island of Andros, in the hand of Cristoforo Buondelmonti![]() in 1422 (today housed

in the Biblioteca Laurenziana, Plut.69,27). In spite of its being confined

originally to a tight circle of Florentine Humanists in the fifteenth century,

its content would become enormously popular at the end of the century, with

the dissemination of the new sensibility represented by Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia

Poliphilii (written around 1467 and published in Venice by Aldo Manuzio

in 1422 (today housed

in the Biblioteca Laurenziana, Plut.69,27). In spite of its being confined

originally to a tight circle of Florentine Humanists in the fifteenth century,

its content would become enormously popular at the end of the century, with

the dissemination of the new sensibility represented by Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia

Poliphilii (written around 1467 and published in Venice by Aldo Manuzio![]() , in

1499). The editio princeps, in Greek, of the Hieroglyphiká, was

published by Manuzio in 1505 and enjoyed more than 30 editions and

translations during the sixteenth century, not including all the adaptations.

, in

1499). The editio princeps, in Greek, of the Hieroglyphiká, was

published by Manuzio in 1505 and enjoyed more than 30 editions and

translations during the sixteenth century, not including all the adaptations.

The Hieroglyphiká

offered a treasure trove of new allegories that the humanists utilized either

directly in their works – such as the famous Ehrenpforte, by Albrecht

Dürer – or, more commonly, by consulting the very complete and systematic

compilation undertaken by Giovanni Pierio Valeriano![]() , also

entitled Hieroglyphica (editio princeps 1556). But the major

relevance of Horapollo’s book consisted mainly of inaugurating a new and

widely disseminated model of symbolic communication.

, also

entitled Hieroglyphica (editio princeps 1556). But the major

relevance of Horapollo’s book consisted mainly of inaugurating a new and

widely disseminated model of symbolic communication.

Beginning with the

previously cited Ennead V.8 of Plotinus, along with the commentaries of

Ficino, hieroglyphic representation was understood as an immediate, total and

almost divine form of knowledge, as opposed to the mediated, incomplete and

temporal form appropriate to discursive language. These ideas inspired not

only Ficino or Giordano Bruno, but also Erasmus![]() ,

Athanasius Kircher and even Leibniz. On the other hand, this work initiated

the mode of "writing with mute signs" (Alciato

,

Athanasius Kircher and even Leibniz. On the other hand, this work initiated

the mode of "writing with mute signs" (Alciato![]() ) –

as expressed in the preface of so many emblem books – thus contributing

decisively to the evolution and popularity of the emblematic genre. In fact,

as Mario Praz has pointed out, in this period emblems were normally seen as

the modern equivalents of sacred Egyptian signs.

) –

as expressed in the preface of so many emblem books – thus contributing

decisively to the evolution and popularity of the emblematic genre. In fact,

as Mario Praz has pointed out, in this period emblems were normally seen as

the modern equivalents of sacred Egyptian signs.

www.studiolum.com

Horapollo

Horapollo (from Horus Apollo, Ὡραπόλλων) is supposed author of a treatise on Egyptian hieroglyphs, extant in a Greek translation by one Philippus, titled Hieroglyphiká, dating to about the 5th century. Horapollo is mentioned by the Suda (ω 159) as one of the last leaders of Ancient Egyptian priesthood, at a school in Menouthis, near Alexandria, during the reign of Zeno (474–491 AD). According to Suda, Horapollo had to flee because he was accused of plotting a revolt against the Christians, and his temple to Isis and Osiris was destroyed. Horapollo was later captured and after torture converted to Christianity. Another, earlier, Horapollo alluded to by the Suda was a grammarian from Phanebytis, under Theodosius II (408–450 AD). To this Horapollo the Hieroglyphiká was attributed by most 16th century editors, although there were more occult opinions, identifying Horapollo with Horus himself, or a with a pharaoh.

The text of the Hieroglyphiká

consists of two books, containing a total of 189 explanations of Egyptian

hieroglyphs. The text was discovered in 1422 on the island of Andros, and was

taken to Florence by Cristoforo Buondelmonti![]() (it is today kept at the

Biblioteca Laurenziana, Plut. 69,27). By the end of the 15th century, the text

became immensely popular among humanists, with a first printed edition of the

text appearing in 1505, initiating a long sequence of editions and

translations. From the 18th century, the book's authenticity was called into

question, but modern Egyptology regards at least the first book as based on

real knowledge of hieroglyphs, although confused, and with baroque symbolism

and theological speculation, and the book may well originate with the latest

remnants of Egyptian priesthood of the 5th century.

(it is today kept at the

Biblioteca Laurenziana, Plut. 69,27). By the end of the 15th century, the text

became immensely popular among humanists, with a first printed edition of the

text appearing in 1505, initiating a long sequence of editions and

translations. From the 18th century, the book's authenticity was called into

question, but modern Egyptology regards at least the first book as based on

real knowledge of hieroglyphs, although confused, and with baroque symbolism

and theological speculation, and the book may well originate with the latest

remnants of Egyptian priesthood of the 5th century.

This approach of symbolic speculation about hieroglyphs (many of which were originally simple syllabic signs) was popular during Hellenism, whence the early Humanists, down to Athanasius Kirchner, inherited the preconception of the hieroglyphs as a magical, symbolic, ideographic script.

The second part of book II treats animal symbolism and allegory, essentially derived from Aristotle, Aelian, Pliny and Artemidorus, and are probably an addition by the Greek translator.

Horapollon ou Horus Apollon est un philosophe alexandrin qui a vécu dans la deuxième moitié du Ve siècle. Il est issu d’une famille aisée, originaire du village de Phénébythis, près d'Akhmîm. On l'appelle également Horapollon de Phénébythis. Son grand-père et homonyme, Horapollon le grammairien, enseignait à Ménouthis près d'Alexandrie. Horapollon le philosophe suit son exemple et se fait le défenseur des traditions.

Le groupe de philosophes auquel il se rattache cherche avec curiosité les vestiges de l'antique civilisation. L'écriture des monuments pharaoniques retient son attention. Il rédige ainsi, en copte, Hieroglyphiká, un ouvrage inspiré de glyphes provenant de monuments égyptien ainsi que d'ouvrages antérieurs sur le sujet; on y retrouve environ un tiers des textes de Chérémon (milieu du Ier siècle). Horapollon puise parfois aux bonnes sources, certaines idées se retrouvent dans un ouvrage philosophique très ancien, conservé par une copie exécutée sous le roi Taharqa: «C'est le cœur qui prend toutes les déterminations et la langue qui répète ce qu'a pensé le cœur.»

Ses Hieroglyphiká

se répartissent en deux livres, traduits en grec par un certain Philippos. Le

texte primitif paraît avoir été assez maltraité. Une copie du manuscrit

grec est découverte en 1419, dans l'île d'Andros, par Buondelmonti![]() . Le texte

est diffusé à Florence quelques années après puis édité pour la première

fois en 1505 à Venise par Alde Manuce.

. Le texte

est diffusé à Florence quelques années après puis édité pour la première

fois en 1505 à Venise par Alde Manuce.

Le livre a une très grande influence sur la littérature savante et ésotérique du XVIe siècle et au delà. Les livres d'emblèmes le citent souvent comme source: «Aussi avons nous apprins d’Orus Apollo & autres, que la corneille est prinse pour une marque de concorde.»

Horapollon exerce également une grande influence sur les débuts de l'égyptologie, mais malheureusement dans un sens assez peu favorable. Bien qu'ayant vécu longtemps après la disparition des hiéroglyphes, Horapollon possédait une connaissance de l'écriture perdue et ses explications du système sont souvent correctes. En revanche, elles sont profondément allégoriques car destinées à un auditoire grec qui a longtemps cru au symbolisme mystique des signes hiéroglyphiques. La preuve en est fournie par une série d'espèces animales dont quelques-unes n'ont jamais figuré dans les hiéroglyphes. La fantaisie est reine: «fils» est représenté par une oie en raison de l'amour extrême que les oies ressentent pour leur progéniture plus que les autres animaux; «ouvrir», par le lièvre qui a toujours les yeux ouverts; «cinq», par l'étoile, à cause des planètes dont les mouvements règlent la marche du monde.

Jean-François Champollion émet, dès 1824, l'idée que: «Horapollon n'est qu'un guide propre à égarer ceux qui se confient à lui. Ses prétendus hiéroglyphes sont des anaglyphes, c'est-à-dire un genre de peinture allégorique très distincte, et des hiéroglyphes phonétiques, et des hiéroglyphes idéographiques; et c'est surtout au trop d'attention accordé à cet auteur et à la prévention où l'on était que ses hiéroglyphes étaient les seuls, les vrais hiéroglyphes, que sont dues les rêveries de tant d'hommes habiles sur ce sujet.»